Abstract

Background

Most of the studies published to date which assess the role of antibacterial sutures in surgical site infection (SSI) prevention include heterogeneous groups of patients, and it is therefore difficult to draw conclusions. The objective of the present study was to investigate whether the use of Triclosan-coated barbed sutures (TCBS) was associated with a lower incidence of incisional SSI and lower duration of hospital stay compared to standard sutures, in elective laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery.

Method

Observational including patients who underwent elective colorectal cancer laparoscopic surgery between January 2015 and December 2020. The patients were divided into two groups according to the suture used for fascial closure of the extraction incision, TCBS vs conventional non-coated sutures (CNCS), and the rate of SSI was analysed. The TCBS cases were matched to CNCS cases by propensity score matching to obtain comparable groups of patients.

Results

488 patients met the inclusion criteria. After adjusting the patients with the propensity score, two new groups of patients were generated: 143 TCBS cases versus 143 CNCS cases. Overall incisional SSI appeared in 16 (5.6%) of the patients with a significant difference between groups depending on the type of suture used, 9.8% in the group of CNCS and 1.4% in the group of TCBS (OR 0.239 (CI 95%: 0.065–0.880)). Hospital stay was significantly shorter in TCBS group than in CNCS, 5 vs 6 days (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

TCBS was associated with a lower incidence of incisional SSI compared to standard sutures in a cohort of patients undergoing elective laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common complication after abdominal surgery. The incidence in elective colorectal surgery can be as high as 20% although there is considerable variation between hospitals [1]. SSI after colorectal surgery increases morbidity and mortality, hospital stay, and healthcare costs [2, 3].

Multiple risk factors related to the patient, surgical procedures, and perioperative care have been described. Some of these are modifiable aspects and constitute important targets with a view to reducing SSI risk [4]. In recent years, the prevention of SSI has become a priority for surgical services and healthcare institutions. In this regard, the introduction of preventive bundle programmes which incorporate various evidence-based preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative interventions has been shown to effectively reduce SSI rates [5,6,7].

Current evidence demonstrates that the type of suture may determine the risk of SSI [8]. Bacterial colonisation of the suture is one of the risk factors for SSI that has been described [9]. To prevent this colonisation, sutures with antibacterial activity have been developed, and Triclosan is currently the antiseptic most widely used to coat sutures due to the effectiveness demonstrated by in vitro and in vivo studies [10]. Published randomised controlled trials on the role of Triclosan-coated sutures and subsequent meta-analyses have reported conflicting results [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. To date, the largest review of RCT both in terms of number of studies and participants has demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of triclosan-coated sutures in reducing SSI [18]. Most of these studies include different pathologies, surgical approaches, and degrees of contamination, all of which make it difficult to draw conclusions about their effectiveness in elective colorectal surgery.

Barbed sutures provide a homogeneous distribution of tension along the suture line avoiding segmental ischaemia, tissue necrosis and consequently may contribute to decreasing the risk of infection. To our knowledge, there are no studies which evaluate the role of TCBS in reducing SSI in elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

The primary objective of the present study was to assess whether the use of Triclosan-coated barbed sutures (TCBS) could reduce the incidence of incisional SSI after elective laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. The secondary objective was to determine its impact on hospital stay.

Materials and methods

An observational retrospective study was carried out in patients who underwent elective colorectal cancer laparoscopic surgery between January 2015 and December 2020. The patients were divided into two groups according to the suture used for fascial closure of the extraction incision, TCBS vs conventional non-coated sutures (CNCS), and the rate of SSI was analysed. This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of our hospital. The inclusion criteria of the study were: age over 18 years, elective surgery, laparoscopic surgical approach, and diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer. The exclusion criteria were: conversion to open approach, abdominal-perineal resection, palliative surgery, postoperative reintervention for reasons other than SSI, postoperative death and loss of follow-up. All patients signed the institution informed consent for laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

Throughout the entire study period, the same bundle of SSI preventive measures was applied [19]. The protocol includes the removal of body hair with clippers 30–60 min before surgery, body hygiene with chlorhexidine soap, antibiotic prophylaxis, antiseptic preparation of the surgical field with 2% chlorhexidine-alcohol, maintenance of body temperature above 36 °C during the procedure, and maintenance of intra- and postoperative blood glucose below 200 mg/dL. The antibiotic prophylaxis (metronidazole 500 mg and cefuroxime 1500 mg or ciprofloxacin 400 mg in case of beta-lactamase allergy) was administered one hour before the intervention, and the antibiotic dosage was repeated for surgeries lasting more than four hours. Mechanical bowel preparation was only used in rectal surgery. Immediately before the abdominal wounds were closed, the surgical instruments and gloves were renewed. A wound protector device was used in all cases.

Surgery was performed following oncological surgical principles. A Hasson trocar was used in the umbilical port and the rest of the trocars were placed according to the type of surgery. The surgical specimen extraction incision was always transverse and located in the right upper quadrant or left iliac fossa according to the location of the tumor. The length of the incision was the minimum necessary required for the extraction of the surgical specimen, and was never greater than 10 cm. Staplers were used for skin closure in all cases. All operations were performed by the same group of dedicated colorectal surgeons, all of whom had more than ten years of experience in laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

TCBS (Ethicon STRATAFIX™ Symmetric PDS™ Plus Knotless Tissue Control Device) has been used after its introduction in our center unless unavailable. Previously, polyglactin 920 CNCS were used for fascial closure in our routine practice.

The definition of SSI was “an infection that occurred within the first 30 days after the intervention that met any of the following criteria: infection of an anatomical plane due to one of the following manifestations: collection, inflammatory signs (pain, swelling, tenderness, redness), dehiscence or positive culture [20]. SSI was classified according to the anatomical plane as: superficial incisional SSI, infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues; Deep incisional SSI, deep soft tissue infection, (fascia and muscles); and organ / space. [20] In our study only incisional SSI were analysed. Patients were physically assessed in the outpatient clinic by a nurse and the surgeon who operated on the patient. Emergency and clinical records of the patients' primary care physician were also reviewed to avoid missing SII. Follow-up to diagnose SSI was performed within 30 days after surgery.

The study variables were: age, sex, ASA score, comorbidity Charlson’s index, preoperative serum albumin and haemoglobin (Hb), leucocyte and lymphocyte count, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, non-dependent insulin diabetes, insulin-dependent diabetes, location of the primary tumor (colon or rectum), operative time, type of suture used to close the fascia, need for perioperative transfusion and tumoral stage. The outcome variables were the incisional (superficial or deep) SSI of surgical specimen extraction wound and hospital stay. The TCBS cases were matched to CNCS cases by propensity score matching to obtain comparable groups of patients.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was performed. Qualitative variables were expressed as total number (relative frequency) and quantitative variables as median (range). The χ2 test and Fisher's test were performed when indicated. Odds ratios were calculated. Non-parametric tests (U-Mann–Whitney and Kruskall-Wallis tests) were used. Optimal cut-off points of quantitative variables were calculated based in ROC curves with the highest sensitivity and specificity values.

To obtain two completely comparable group of patients and to reduce possible selection bias, a matched cases study depending on the suture used was performed by matching propensity index adjusted by following variables: diabetes, colon vs rectum location, surgical procedure, and preoperative transfusion. The matching algorithm was the closest neighbor and the estimation algorithm was performed using logistic regression. The matching rate was 1: 1 without restitution. Propensity score matching performed on data from observational studies reduces the risk of including confounding variables. Therefore, many authors point out that the way to objectively extract causality in observational studies would be through the use of these matching techniques [21,22,23,24,25], even with small sample sizes [26].

After matching, a prognostic model of incisional SSI based in binary logistic regression was created with selected patients. Binomial negative regression was calculated to find independent prognostic factors for hospital stay. Multicollinearity was studied with variance inflation index (VIF) in both cases of regression. The p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was carried out with software R version 3.6.0. Statistical method was supervised by the INCLIVA Research Foundation team. Statistician was not blind to the data. Only the personal data of the patients were anonymised.

Results

Outcomes of total cohort before propensity score matching

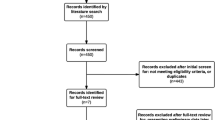

During the study period, a total of 612 colorectal cancer patients underwent laparoscopic elective surgery. Of these, a total of 488 patients met the study inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study are outlined in Table 1. Overall incisional SSI was observed in 24 (4.9%) patients. Of the quantitative variables studied, the only one that showed statistically significant correlation with incisional SSI was BMI (p = 0.026).

The qualitative variables studied that have been shown to increase the risk of incisional SSI are outlined in Table 2.

Logistic regression based on the variables related to the incisional SSI identified as independent prognostic variables the BMI (p = 0.044) and the need for postoperative transfusion (p = 0.007).

Overall median hospital stay was 6 days (range: 2–43 days). In the case of patients with incisional SSI, the median stay was 7 days (range: 4–42 days) versus 6 days (range: 2–43 days) (p = 0.001) in patients without wound complications. The variables related to hospital stay were age (p < 0.001), diabetes (p = 0.011), non-insulin-dependent diabetes (p = 0.042), chronic renal failure (p = 0.038), ASA stage (p = 0.010), Charlson´s index (p = 0.001), lymphocyte count (p < 0.001), lymphocyte neutrophil rate (p = 0.001), lymphocyte neutrophil lymphocyte derived rate (p < 0.002), pre and postoperative serum Hb value (p = 0.016 and p = 0.021, respectively), tumor location (p = 0.001), operative time (p = 0.002), type of suture used (p < 0.001), need for postoperative transfusion (p < 0.001), and incisional SSI (p = 0.001). Predictive variables for hospital stay were age (p = 0.0128, VIF = 1.2610), operative time (p < 0.001, VIF = 1.05234), type of suture (p = 0.0033, VIF = 1.0267), need for postoperative transfusion (p < 0.001, VIF = 1.0497), and presence of SSI (p < 0.001, VIF = 1.0344).

The study of the characteristics of the groups formed by the two types of sutures showed significant differences in the median operative time (p = 0.029), preoperative leukocyte (p = 0.031) and lymphocyte count (p = 0.028), diabetes (p = 0.018), need for pre-transfusion (p = 0.003) and colon location of the neoplasm (p = 0.005).

The above variables were considered as possible confounding variables and were introduced in the propensity score matching. As a result, the groups obtained after matching were completely comparable.

Outcomes after propensity score matching

After adjusting the patients with the propensity score, two new groups of patients were generated: 143 TCBS cases versus 143 CNCS cases. Overall incisional SSI appeared in 16 (5.6%) of the patients with a significant difference between groups according to the type of suture used, 9.8% in the group of CNCS and 1.4% in the group of TCBS (OR 0.239 (CI 95%: 0.065–0.880)).

The factors related to incisional SSI were the Charlson´s index (p = 0.001), use of CNCS (p = 0.003), tumor stage (p = 0.020), diagnosis of diabetes (p = 0.012) and non- insulin-dependent diabetes (p = 0.005). The risk of incisional SSI was higher in patients with a Charlson´s index ≥ 6 (OR: 2.679, 95% CI: 2.679–4.146), as well as in patients with diabetes (OR: 2.685; 95% CI: 1.447–4.980), especially those treated with oral antidiabetic drugs (OR: 3.193; 95% CI: 1.698–6.001) and if CNCS were used (OR: 1.831; 95% CI: 1.465–2.290). The TCBS showed a protective effect on incisional SSI (OR: 0.239; 95% CI: 0.065–0.880) decreasing in 76.1% the risk of incisional SSI. The ability to avoid an incisional SSI was 4.184 times higher with this suture than with CNCS.

In the multivariate analysis, the independent prognostic variables identified were the Charlson’s index (p = 0.018), non-insulin-dependent diabetes (p = 0.003) and the use of TCBS (p = 0.003) Fig. 2. The ROC curve for this model was 91% AUC (95% CI: 0.80–0.98). The sensitivity of the model was 91.5% and the specificity was 87.5%. (Fig. 3).

After matching the cases, the predictive variables for hospital stay were operative time (p < 0.001, VIF = 1.0349), type of suture (p = 0.0052, VIF = 1.0411) and need for postoperative transfusion (p < 0.001, VIF = 1.0523).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the use of TCBS for fascial closure after elective laparoscopic surgery in patients with colorectal cancer decreased the risk of incisional SSI. Overall SSI was 5.6%, with a significant difference between groups depending on the type of suture used, 9.8% in the group of a CNCS and 1.4% in the group of TCBS (OR 0.239 (CI 95%: 0.065–0.880)). Due to the use of TCBS, the risk of SSI decreased by 76.1%. In other words, the probability of avoiding an SSI are 4.18 times more likely with these sutures than with CNCS. On the other hand, the hospital stay was significantly shorter in the TCBS group, which, although not the target of this study, could lead to savings in hospital costs. Since the introduction of TCBS in our hospital, this suture has gradually replaced CNCS in our clinical practice. We have maintained a prospective database for years and have chosen the study period because we have used the same bundle of SSI preventive measures and the same perioperative protocols throughout the study period. The only change was the introduction of TCBS for fascial closure. The TCBS cases were matched to CNCS cases by propensity score matching to obtain comparable groups.

Patients undergoing colorectal surgery have a higher rate of SSI than other abdominal surgical procedures [27]. The laparoscopic approach in colorectal surgery has been shown to be a protective factor for SSI, decreasing the risk compared to laparotomy [4, 28,29,30,31]. Several risk factors for SSI in patients with colorectal cancer have been described, relative to both the patient as well as to the surgical procedure or perioperative care. A recent meta-analysis showed that obesity, male gender, diabetes mellitus, ASA score ≥ 3, stoma creation, intraoperative complications, perioperative blood transfusion and operation time ≥ 180 min were significant risk factors for SSI [4]. In our study the factors associated with an increased risk of SSI were BMI ≥ 28, Charlson Index ≥ 6, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, post-operative transfusions, colon surgery and CNCS use. To avoid bias and to obtain two comparable groups according to whether TCBS or CNCS were used, the aforementioned risk factors were used as covariates in the propensity score matched study. The independent prognostic factors identified were Charlson Index ≥ 6, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and TCBS. The prognostic model obtained with these factors showed an AUC of 91%. The model created could be useful to identify high-risk patients who might develop SSI.

The outcomes of triclosan-coated sutures in abdominal surgery are controversial. Some studies indicated that triclosan sutures have a protective effect against SSI [13,14,15,16,17,18] while others showed no beneficial effect [11, 12]. Most of these studies included different pathologies, surgical approaches and degrees of contamination, all of which make it difficult to draw conclusions regarding their effectiveness in elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Sandini et al., in a meta-analysis including six RCTs involving 2168 patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery, did not demonstrate a significant SSI protective effect of triclosan-coated sutures over CNCS. The overall SSI rate was 11.7% in the triclosan group and 13.4% in the control group (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.58–1.13) [32]. The range of SSI incidence was wide (6.8%–16.8%) and the studies included different suture types, wall closure techniques and definitions of SSI, all of which limited the interpretation of the results. Four of the RCTs included exclusively patients with colorectal surgery, open and laparoscopic approach, with contradictory results. Two of them found that triclosan-coated sutures reduced the incidence of SSI [33, 34], while the other two observed no difference with non-coated sutures [35, 36]. Although the level of evidence is moderate to low, several organisations and clinical guidelines recommend the use of triclosan-coated sutures regardless of the type of surgery [37,38,39].

Barbed sutures allow a homogeneous distribution of tension along the suture preventing segmental ischaemia, tissue necrosis and secondary infection. Furthermore, they avoid the need for knots, reduce incision closure time and provide better waterproofing compared to CNCS. The synergistic effect of the combination of barbed suture and triclosan coating in reducing the incidence of SSI and other complications such as wound dehiscence has been poorly studied to date. A Spanish randomised clinical trial assessed the effect of using triclosan-coated barbed suture for fascial closure on SSI and evisceration after emergency surgery. Incisional SSI was significantly lower (6.4%) in the triclosan-coated barbed suture group than in the triclosan-coated CNCS group (8.9%) and in the uncoated suture group (23.4%, p = 0.03). The evisceration rate was 0% in the barbed suture group and 8.9% and 12.8%, respectively in the other groups (p = 0.05). The authors concluded that triclosan-coated sutures reduced the risk of SSI and barbed sutures reduced the risk of evisceration and therefore triclosan-coated barbed sutures should be recommended for fascial closure in emergency open surgery [40]. More recently, Johnson et al. have published a multi-institutional, single-arm, retrospective cohort study of patients undergoing open colorectal surgery in which wound closure was performed with triclosan-coated barbed suture. Data were obtained from the Premier Healthcare Database, a database of US hospitals. The overall incidence of wound complications was 7.1%, with the majority being SSIs (6.0%) [41]. [34] To our knowledge, the present study is the first one to have analysed the impact of triclosan-coated barbed suture for fascial closure on the reduction of incisional SSI in patients with colorectal cancer who have undergone elective laparoscopic surgery.

Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of this study. It was an observational study conducted in a single centre and with a selected group of pathologies. In this light its conclusions should be viewed with caution. The retrospective nature of the study could include a possible bias in the selection of the suture for fascial closure. The inclusion only of patients with colorectal cancer could mean that the results cannot be extrapolated to other colorectal pathologies. In the control group, several types of uncoated sutures were used according to the surgeon's preference. In the control group we used polyglactin 920, which is not standard practice for many surgeons and may limit the external validity of the study. In addition, oral antibiotic prophylaxis and mechanical bowel preparation was not used in colon cases and this could reduce the SSI rate. The strengths of this study were that a homogeneous group of patients was included, electively operated on by the same group of colorectal surgeons, with strict protocols for both SSI prevention and perioperative care which remained stable throughout the study period and with extensive patient follow-up. In addition, to reduce potential patient selection bias, propensity score matching was used. This study also provided a prediction model for the risk of wound infection with an area under the curve of 91%, a sensitivity of 91.5% and a specificity of 87.5%.

In conclusion, the use of TCBS in elective laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery could reduce the incidence of incisional SSI and the length of hospital stays. As this is the most frequently performed procedure in colorectal surgery units, our results could have an important beneficial impact for patients and for the health care system. Well-designed randomised clinical trials are needed to obtain further scientific evidence on the effectiveness of TCBS in reducing SSI and other wound complications in colorectal surgery.

References

Pujol M, Limón E, López-Contreras J, Sallés M, Bella F, Gudiol F (2012) Surveillance of surgical site infections in elective colorectal surgery. Results of the VINCat Program (2007–2010). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin [Internet]. 30(Suppl. 3):20–25

Broex ECJ, van Asselt ADI, Bruggeman CA, van Tiel FH (2009) Surgical site infections: how high are the costs? J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 72(3):193–201

Piednoir E, Robert-Yap J, Baillet P, Lermite E, Christou N (2021) The socioeconomic impact of surgical site infections. Front Public Heal. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.712461

Xu Z, Qu H, Kanani G, Guo Z, Ren Y, Chen X (2020) Update on risk factors of surgical site infection in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 35(12):2147–2156

Keenan JE, Speicher PJ, Thacker JKM, Walter M, Kuchibhatla M, Mantyh CR (2014) The preventive surgical site infection bundle in colorectal surgery an effective approach to surgical site infection reduction and health care cost savings. JAMA Surg 149(10):1045–1052

Gorgun E, Rencuzogullari A, Ozben V, Stocchi L, Fraser T, Benlice C et al (2018) An effective bundled approach reduces surgical site infections in a high-outlier colorectal unit. Dis Colon Rectum 61(1):89–98

Falconer R, Ramsay G, Hudson J, Watson A (2021) Reducing surgical site infection rates in colorectal surgery—a quality improvement approach to implementing a comprehensive bundle. Color Dis 23(11):2999–3007

Rahbari NN, Knebel P, Diener MK, Seidlmayer C, Ridwelski K, Stöltzing H et al (2009) Current practice of abdominal wall closure in elective surgery? Is there any consensus? BMC Surg 9(1):1–8

Gristina AG, Price JL, Hodgood CD, Webb LX, Costerton J (1985) Bacterial colonization of percutaneous sutures. Surgery 98(1):9–12

Ming X, Rothenburger S, Nichols MM (2008) In vivo and in vitro antibacterial efficacy of PDS plus (polidioxanone with triclosan) suture. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 9(4):451–457

Chang WK, Srinivasa S, Morton R, Hill AG (2012) Triclosan-impregnated sutures to decrease surgical site infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg 255(5):854–859

Diener MK, Knebel P, Kieser M, Schüler P, Schiergens TS, Atanassov V et al (2014) Effectiveness of triclosan-coated PDS Plus versus uncoated PDS II sutures for prevention of surgical site infection after abdominal wall closure: the randomised controlled PROUD trial. Lancet 384(9938):142–152

Justinger C, Slotta JE, Ningel S, Gräber S, Kollmar O, Schilling MK (2013) Surgical-site infection after abdominal wall closure with triclosan-impregnated polydioxanone sutures: Results of a randomized clinical pathway facilitated trial (NCT00998907). Surg (United States) 154(3):589–595

Wang ZX, Jiang CP, Cao Y, Ding YT (2013) Systematic review and meta-analysis of triclosan-coated sutures for the prevention of surgical-site infection. Br J Surg 100(4):465–473

Edmiston CE, Daoud FC, Leaper D (2014) Is there an evidence-based argument for embracing an antimicrobial (triclosan)-coated suture technology to reduce the risk for surgical-site infections? A meta-analysis. Surgery 155(2):362–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2013.11.002

de Jonge SW, Atema JJ, Solomkin JS, Boermeester MA (2017) Meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of triclosan-coated sutures for the prevention of surgical-site infection. Br J Surg 104(2):e118–e133

Guo J, Pan LH, Li YX, Di YX, Li LQ, Zhang CY et al (2016) Efficacy of triclosan-coated sutures for reducing risk of surgical site infection in adults: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Surg Res [Internet]. 201(1):105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.10.015

Ahmed I, Boulton AJ, Rizvi S, Carlos W, Dickenson E, Smith NA et al (2019) The use of triclosan-coated sutures to prevent surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. BMJ Open 9(9):1–12

Sociedad Española de Medicina Preventiva Salud Pública e Higiene [Internet]. Madrid: SEMPSPH; 2012. http://www.sempsph.com/es/noticias?start=30

National Healthcare Safety Network. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surgical site infection (SSI) event. Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI) Introduction : Settings: Requirements [Internet]. www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf (Published January 2017. Accessed Oct 25, 2017).

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika [Internet]. 70(1):41–55

Rubin DB (1997) Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med 127:757–763

Dehejia RH, Wahba S (2002) Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat 84(1):151–161

Li M (2013) Using the propensity score method to estimate causal effects: a review and practical guide. Organ Res Methods 16(2):188–226

Coscia Requena C, Muriel A, Peñuelas O (2018) Análisis de la causalidad desde los estudios observacionales y su aplicación en la investigación clínica en Cuidados Intensivos. Med Intensiva 42(5):292–300

Andrillon A, Pirracchio R, Chevret S (2020) Performance of propensity score matching to estimate causal effects in small samples. Stat Methods Med Res 29(3):644–658

Ata A, Valerian BT, Lee EC, Bestle SL, Elmendorf SL, Stain SC (2010) The effect of diabetes mellitus on surgical site infections after colorectal and noncolorectal general surgical operations. Am Surg [Internet]. 76(7):697–702

Aimaq R, Akopian G, Kaufman HS (2011) Surgical site infection rates in laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery. Am Surg 77(10):1290–1294

Howard DPJ, Datta G, Cunnick G, Gatzen C, Huang A (2010) Surgical site infection rate is lower in laparoscopic than open colorectal surgery. Color Dis 12(5):423–427

Kiran RP, El-Gazzaz GH, Vogel JD, Remzi FH (2010) Laparoscopic approach significantly reduces surgical site infections after colorectal surgery: data from national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg [Internet]. 211(2):232–238

Huh JW, Lee WY, Park YA, Cho YB, Kim HC, Yun SH et al (2019) Oncological outcome of surgical site infection after colorectal cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 34(2):277–283

Sandini M, Mattavelli I, Nespoli L, Uggeri F, Gianotti L (2016) Systematic review and meta-analysis of sutures coated with triclosan for the prevention of surgical site infection after elective colorectal surgery according to the PRISMA statement. Medicine (United States). 95(35):e4057

Nakamura T, Kashimura N, Noji T, Suzuki O, Ambo Y, Nakamura F et al (2013) Triclosan-coated sutures reduce the incidence of wound infections and the costs after colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 153(4):576–583

Rasić Z, Schwarz D, Adam VN, Sever M, Lojo N, Rasić D et al (2011) Efficacy of antimicrobial triclosan-coated polyglactin 910 (Vicryl* plus) suture for closure of the abdominal wall after colorectal surgery. Coll Antropol [Internet]. 35(2):439–443

Baracs J, Huszár O, Sajjadi SG, Peter HO (2011) Surgical site infections after abdominal closure in colorectal surgery using triclosan-coated absorbable suture (PDS Plus) vs Uncoated sutures (PDS II): a randomized multicenter study. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 12(6):483–489

Mattavelli I, Rebora P, Doglietto G, Dionigi P, Dominioni L, Luperto M et al (2015) Multi-center randomized controlled trial on the effect of triclosan-coated sutures on surgical site infection after colorectal surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 16(3):226–235

World Health Organization (2018) Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection.

Allegranzi B, Zayed B, Bischoff P, Kubilay NZ, de Jonge S, de Vries F et al (2016) New WHO recommendations on intraoperative and postoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 16(12):e288-303

Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, Harbrecht BG, Jensen EH, Fry DE et al (2017) American college of surgeons and surgical infection society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg [Internet]. 224(1):59–74

Ruiz-Tovar J, Llavero C, Jimenez-Fuertes M, Duran M, Perez-Lopez M, Garcia-Marin A (2020) Incisional surgical site infection after abdominal fascial closure with triclosan-coated barbed suture vs triclosan-coated polydioxanone loop suture vs polydioxanone loop suture in emergent abdominal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg [Internet]. 230(5):766–774

Johnson BH, Rai P, Jang SR, Johnston SS, Chen BPH (2021) Real-world outcomes of patients undergoing open colorectal surgery with wound closure incorporating triclosan-coated barbed sutures: a multi-institution, retrospective database study. Med Devices Evid Res 14:65–75

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. There is no funding supporting the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Vicente Pla-Martí reports consultancy for Johnson and Johnson (manufactured of the suture, Ethicon STRATAFIX™ Symmetric PDS™ Plus Knotless Tissue Control Device), has received honorarium for speaking at symposia and workshops by Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic and Braun Medical and support for attending meetings by Takeda. José Martín-Arévalo has received honorarium for speaking at workshops by Johnson and Johnson and Medtronic. David Moro-Valdezate has received honorarium for speaking at symposia and workshops by Johnson and Johnson and Medtronic and support for attending meetings by Sanofi. Stephanie García-Botello, Leticia Pérez-Santiago, Ernesto Muñoz-Sornosa, Ana Izquierdo-Moreno and Alejandro Espí-Macías have no conflict of interest nor financial ties to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study were conducted according to the ethical standards of the institution and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of our hospital.

Patient consent

All patients signed the institution informed consent for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. No specific consent for this type of study is required.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not applicable.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Vicente Pla‑Martí and José Martín‑Arévalo share first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pla-Martí, V., Martín-Arévalo, J., Moro-Valdezate, D. et al. Triclosan-coated barbed sutures in elective laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery: a propensity score matched cohort study. Surg Endosc 37, 209–218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09418-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09418-0