Abstract

Background

This study aimed to compare quality of life (QOL), functional outcome, body image, and cosmesis after hand-assisted laparoscopic (LRP) versus open restorative proctocolectomy (ORP). The potential long-term advantages of LRP over ORP remain to be determined. The most likely advantage of LRP is the superior cosmetic result. It is, however, unclear whether the size and location of incisions affect body image and QOL.

Methods

In a previously conducted randomized trial comparing LRP with ORP, 60 patients were prospectively evaluated. The primary end points were body image and cosmesis. The secondary end points were morbidity, QOL, and functional outcome. A body image questionnaire was used to evaluate body image and cosmesis. The Short Form-36 Health Survey and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Inventory were used to assess QOL. Body image and QOL also were assessed preoperatively.

Results

A total of 53 patients completed the QOL and functional outcome questionnaires. There were no differences in functional outcome, morbidity, or QOL between LRP and ORP. At a median of 2.7 years after surgery, 46 patients returned the questionnaires regarding body image, cosmesis, and morbidity. The body image and cosmesis scores of female patients were significantly higher in the LRP group than in the ORP group (body image, 17.4 vs 14.9; cosmesis, 19.1 vs 13.0, respectively). The female patients in the ORP group had significantly lower body image scores than the male patients (14.9 vs 18.3).

Conclusions

This study is the first to show that ORP has a negative impact on body image and cosmesis as compared with LRP. Functional outcome, QOL, and morbidity are similar for the two approaches. The advantages of a long-lasting improved body image and cosmesis for this relatively young patient population may compensate for the longer operating times and higher costs, particularly for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Restorative proctocolectomy is considered the operation of choice for patients with ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis coli. Patients undergoing restorative proctocolectomy may benefit from a laparoscopic approach, as demonstrated by previous studies comparing laparoscopic procedures with open surgery for inflammatory bowel disease [1–4]. Whereas these studies reported on resections confined to only small parts of the bowel, proctocolectomy belongs to the most extensive gastrointestinal resections.

Although the advantages of laparoscopy have been demonstrated in relatively minor procedures, to date they have not been demonstrated for restorative proctocolectomy. The only randomized trial that compared laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy (LRP) using a hand-assisted technique with open restorative proctocolectomy (ORP) indicated that there are no benefits from LRP in terms of early recovery and morbidity [5]. Furthermore, the operating time was increased by 80 min, and the total costs were higher. Other studies, all of them nonrandomized, have shown similar results [6, 7].

Long-term functional results and quality of life (QOL) after LRP have been reported only in a retrospective study [8]. No long-term data are available regarding small bowel obstructions after LRP, which is a significant clinical problem after ORP (incidence, 13–35%) [9–11].

Currently, the superior cosmesis, mentioned frequently [6, 12–14], seems to be a permanent advantage of LRP. The importance of cosmesis is substantiated by the increasing number of patients requesting a referral for laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy to medical centers with expertise in laparoscopic surgery. However, there are no randomized data available assessing the extent to which the size or location of incisions (laparoscopy or laparotomy) affect the patient’s body image or QOL, if it does at all. Furthermore, it is not known whether this possible effect differs between male and female subjects. If the size and location of an incision really does affect body image or QOL, this should be observed particularly after restorative proctocolectomy because the cosmetic advantage of a small Pfannenstiel incision over a full midline incision seems obvious.

The patient population of a previously conducted randomized trial comparing hand-assisted LRP and ORP was used for this study [5]. The current study aimed to compare the results of body image and cosmesis, morbidity, functional outcome, and QOL after LRP and ORP.

Patients and methods

Patients with ulcerative colitis or familial polyposis coli eligible for elective restorative proctocolectomy in a previously conducted randomized controlled trial were prospectively evaluated. In the original study, the patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either hand-assisted laparoscopic or open restorative proctocolectomy. Short-term results regarding perioperative parameters and postoperative recovery 3 months after surgery have been previously published [5]. Methodological and operative details can be found in the original article.

The primary end points of the current study were body image and cosmesis. The secondary end points were morbidity, functional outcome, and QOL. Body image was assessed both pre- and postoperatively, whereas cosmesis and morbidity were assessed only postoperatively. The postoperative assessments of body image, cosmesis, and morbidity after LRP versus ORP were performed in January 2005 for all the patients, a median of 2.7 years after restorative proctocolectomy. Quality of life and functional outcome were assessed exactly 1 year postoperatively for each individual patient.

Functional outcome

Functional outcome in terms of day- and nighttime defecation frequency, incontinence, and sexual (dys)function was evaluated 1 year after surgery using a self-report gastrointestinal functional outcome questionnaire [15].

Quality of life

Overall QOL was measured by the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36). The SF-36, a well-validated generic questionnaire for measuring QOL, consists of eight multi-item scales assessing physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health [16].

Quality of life related to the gastrointestinal tract was assessed by the total score of the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) [17]. The GIQLI, a more disease-specific validated QOL questionnaire, consists of 36 questions with 5 response categories. The GIQLI responses are summed to give a total numeric score. Data from both the SF-36 and GIQLI 1 year postoperatively were compared with data 3 months postoperatively.

Body image and cosmesis

To evaluate body image and cosmesis, the Body Image Questionnaire (BIQ) was used. Body image can be defined as a multidimensional construct that represents how patients think, feel, and behave with regard to their own physical attributes, including their incisional scar(s) [18]. Cosmesis was defined as the degree of explicit satisfaction with the incisional scar(s).

The BIQ has been described previously [19]. In summary, the BIQ consists of eight questions combined to form two scales: a body image scale and a cosmesis scale. Five questions regarding body image assess patients’ perception of their own body and their satisfaction with that perception, while also evaluating patients’ attitude toward their bodily appearance. The body image scale ranges from 5 (lowest body image score) to 25 (highest body image score).

Three questions regarding the cosmetic result after the operation assess the degree of satisfaction with respect to the physical appearance of the incisional scar(s). First, patients were asked to give a score to their scar(s) on a scale from 1 (lowest score) to 10 (highest score). Then the patients were asked to grade the extent to which they were satisfied with their scar on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied). Finally, the patients were asked to describe their scar on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very repulsive) to 7 (very beautiful). The combined scores of these three questions resulted in the cosmesis scale ranging from 3 (lowest satisfaction) to 24 (highest satisfaction). To evaluate the validity of the BIQ, the internal consistency coefficients for both the body image and cosmesis scale were assessed.

A photo series questionnaire (PSQ) was administered to assess whether a patient’s degree of satisfaction with or preference for the two surgical approaches would be affected if he or she were shown photographs of the cosmetic results for the same and alternative approaches, respectively. The PSQ consists of six questions and two photographs of patients who underwent the open approach as well as two photographs of patients who underwent the laparoscopic approach.

The photographs of each procedure were concealed in two different envelopes. First, the patients were asked to give a score to their own incisional scar(s) on a scale of 1 (lowest score) to 10 (highest score). Then they were asked to give a score to the scar(s) on the photographs: first to the photographs of the same procedure, then to the photographs of the alternative procedure. After thus seeing the cosmetic results for the same and alternative surgical approaches, the patients were asked to score their own scar(s) again. In addition, they were asked their preference for one of the two surgical approaches if, hypothetically, they had the choice.

The patients who favored the laparoscopic approach were asked whether and how much they were willing to spend extra in terms of euros to have the laparoscopic operation, supposing that the only differences between the two approaches were the cosmetic result and the costs (higher cost for the laparoscopic approach).

Morbidity

Morbidity was defined as any complication related to the original disease (ulcerative colitis or familial polyposis coli) or the operative procedure in the period beyond 30 days after restorative proctocolectomy. This included readmission or reoperation for clinically significant small bowel obstruction or incisional hernia. For this purpose, patients’ medical files were reviewed. Any complication related to the original disease (ulcerative colitis or familial polyposis coli) or the operation was recorded.

To exclude whether patients were treated in other hospitals, an additional questionnaire regarding potential readmissions or reoperations was sent to all patients. The patients who did not complete the questionnaire were contacted by telephone to obtain the requested information. If a patient did not complete the questionnaire and could not be contacted by phone, follow-up evaluation was considered incomplete. In that case, the patient was not included for the analysis of morbidity.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean and range unless otherwise specified. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare discrete and continuous variables between the two groups. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used when appropriate to compare categorical or dichotomous variables between the two groups. To test for differences between continuous and discrete variables within a group, the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used. For a comparison of QOL results from different time points, a repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure was used.

Results

Functional outcome

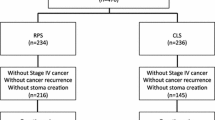

Of the 60 patients randomized to either LRP or ORP and treated with surgery in the period January 2000 and August 2003, 53 returned the questionnaires regarding functional outcome 1 year after surgery (Fig. 1, flowchart, response rate 88.3%). The characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1. The patients in the laparoscopic group were significantly younger than the patients in the open group. The laparoscopic group had fewer male patients than the open group. Although this difference existed already at the time of surgery, it was more pronounced after longer follow-up times because fewer male patients returned the questionnaires.

Within the first year after surgery, a male patient from the laparoscopic group had died of a cholangiocarcinoma that had not been diagnosed at the time of surgery. For this patient, who had a diverting ileostomy, bowel continuity was never restored.

Of the 59 living patients, 4 had a stoma 1 year after the operation. One female patient from the open group had an end-ileostomy 9 months after surgery because the pouch had been excised due to veno-occlusive disease in the pouch. Another female patient from the open group still had a diverting stoma because of a persistent presacral fistula. A male patient from the open group who had undergone a one-stage restorative proctocolectomy presented with a presacral fistula 6 month after the operation. This patient was given an end-ileostomy. A female patient from the laparoscopic group had anastomotic leakage from the linear staple line of the pouch after restoration of bowel continuity. This patient also underwent an ileostomy 1 year after the operation.

Table 2, presents the results of functional outcome. Overall, the median defecation frequency was five times during the day and one time during the night. For 14.3% of the patients, minor incontinence occurred more than three times a week. One patient from the open group experienced severe incontinence, which occurred less than once a week. More than 70% of the patients were able to postpone defecation for at least 15 min. Of the 25 female patients reported to be sexually active, 6 (24%) experienced moderate to severe dyspareunia. Of the 10 male patients reported to be sexually active, 1 experienced retrograde ejaculation. None of the evaluated factors regarding functional outcome differed significantly between the open and laparoscopic groups.

Quality of life

A total of 53 patients returned the questionnaires regarding QOL 1 year after their surgery (Fig. 1, flowchart). The QOL of these patients continued to improve until 1 year after surgery (data not shown). The difference between the 1-year and 3-month time points was statistically significant for all scales of the SF-36 and for the total score of the GIQLI in both groups (p < 0.05 for all subscales of the SF-36 and the GIQLI total score). There was, however, no significant difference between the LRP and ORP groups.

Long-term morbidity

A total of 46 patients, 23 from each group, completed the questionnaire regarding readmissions and reoperations for small bowel obstruction or incisional hernia (Fig. 1, flowchart). Because the questionnaires were sent to all the patients at the same time (January 2005), the follow-up data for each patient were different depending on the date of operation. The median follow-up period was 2.7 years (range, 1.4–5.5 years). Five patients in the laparoscopic group and three in the open group were readmitted. The indication for the readmission of the five laparoscopic patients was an incisional hernia at the former stoma site in one patient and suspected small bowel obstruction in the remaining four patients.

The patient with incisional hernia and one of the patients readmitted for suspected small bowel obstruction underwent reoperation. During the operation, a small bowel herniation through the major omentum proved to be the cause of the obstruction. The indication for the readmission of the three open group patients was suspected small bowel obstruction in all three. One of the three readmitted patients in the open group actually underwent reoperation. Adhesions were found to be the cause of the obstruction.

Body image and cosmesis

A total of 46 patients, 23 from each group, completed the BIQ questionnaire at a median follow-up assessment of 2.7 years (range, 1.4–5.5 years) (Fig. 1, flowchart). The internal consistency coefficients were 0.83 for the body image scale and 0.85 for the cosmesis scale. There were no significant differences in pre- and postoperative body image scores between the LRP and ORP groups at either time point (p = 0.930 and p = 0.192, respectively). The cosmesis score (measured only postoperatively) for the LRP group (18.5) was higher than that for the ORP group (14.7) (p = 0.010).

To assess the effect of the surgical approach on body image and cosmesis scores within gender, the male and female patients were analyzed separately. The females who underwent laparoscopic surgery reported significantly higher body image and cosmesis scores than those who underwent open surgery (Fig. 2, p = 0.029 and p = 0.006, respectively). Among the male patients, there were no differences between the two surgical approaches.

To evaluate the effect of gender on body image and cosmesis scores, outcome per surgical approach was analyzed. In the open group, the female patients had significantly lower body image scores than the male patients (Fig. 3, p = 0.004). Although the cosmesis scores also were lower for the females, the difference between the sexes was not significant (Fig. 3, p = 0.238). In the laparoscopic group, there were no differences in body image or cosmesis scores between the sexes.

The results of the PSQ are presented in Table 3. The patients in the laparoscopic group rated their scar(s) with higher scores than the patients in the open group. The patients in the laparoscopic group rated the pictures of the open approach (5.1) comparably with the personal ratings of the patients who underwent the operation by the open approach (5.7). Conversely, the patients in the open group rated the pictures of the laparoscopic approach (8.7) comparably with the personal ratings of the patients who underwent the operation by the laparoscopic approach (7.9).

The satisfaction of the patients with their own scars did not change significantly after they had seen the photos for the alternative approach (from 7.9 to 7.9; p = 0.904 and 5.7 to 5.5; p = 0.168, respectively). None of the patients in the laparoscopic group preferred the open approach if they had the choice. The laparoscopic approach was preferred by 65% of the patients in the open group. Two-thirds of the patients in the laparoscopic group and almost half of the patients in the open group were willing to spend an extra amount of euros to have the laparoscopic approach if they had the choice.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that the open approach for restorative proctocolectomy had a significant negative impact on body image and cosmesis in female patients compared with those who underwent a laparoscopic approach. Although a relatively small number of patients were included, this is the only randomized study reporting on long-term morbidity, functional outcome, and QOL after laparoscopic versus traditional open restorative proctocolectomy.

The results for functional outcome and QOL 1 year after the laparoscopic approach were comparable with those after the open approach. For QOL, this was not unexpected because there also were no differences between the two groups at the 3-month time point. Although a difference in functional outcome between the two procedures was not expected, no studies have ever reported on functional outcome after LRP versus ORP. In accordance with studies reporting on QOL after ORP, the QOL for these patients was comparable with that for the general population [20–22].

Restorative proctocolectomy is a major colorectal operation associated with considerable morbidity. Small bowel obstruction caused by adhesions is one of the most commonly encountered complications after restorative proctocolectomy, as shown by both short- and long-term postoperative follow-up assessments. Small bowel obstruction is reported to occur in 13% to 35% of the patients, depending both on its definition and the length of the postoperative follow-up period [9–10, 23, 24].

Only a minority of obstructive episodes require surgical intervention. Laparoscopy may decrease the incidence of small bowel obstruction because fewer adhesions are expected to develop than after a laparotomy [25]. In the current study, 7 (15.2%) of the 46 patients were readmitted for suspected small bowel obstruction within a median follow-up period of 2.7 years. These numbers are relatively low compared with those of other studies with a comparable follow-up period [9–24, 26, 27]. In the current study, however, only clinically significant episodes were recorded. Only two patients, one from each group, actually required reoperation for this reason. These numbers are too small for conclusions to be drawn.

It is possible that the open proctectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision after the hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy, which was the operative procedure for these patients, counterbalanced some of the potential advantages of the minimally invasive approach in relation to adhesion formation. To test this hypothesis, a total laparoscopic proctocolectomy (i.e., a combined laparoscopic colectomy and laparoscopic proctectomy) should be compared with the hand-assisted approach as adopted for the patients in this study [6–28]. Several studies have shown that restorative proctocolectomy can be performed by a total laparoscopic approach as well. Whether there are clinically relevant advantages for one of the two approaches remains to be determined.

In contrast to cosmetic surgery, body image and cosmesis are unconventional outcomes in the field of general surgery. Accelerated postoperative recovery, lower morbidity, and shorter hospital stay are considered the fundamental advantages of laparoscopy. It must be realized that for the patient, these are only nonpersisting short-term benefits. Conversely, improved cosmesis and body image, usually mentioned only as additional advantages, may be long-lasting advantages of the laparoscopic approach. As demonstrated in this study, body image and cosmesis were better after LRP than after ORP.

The internal consistency of the BIQ was high, and it was able to detect a difference between open and laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy and between the sexes, which indicates its validity for evaluation of body image and cosmesis. The differences were most prominent in female patients. This is consistent with the reports in the literature about gender differences. In the general population, men experience much less body dissatisfaction than women [29, 30].

A potential confounding factor could be that patients in the open group were significantly older (median age, 38 vs 29 years in ORP vs LRP, respectively; p = 0.023). There are data suggesting that age indeed plays a role in body image. There is some evidence that older women have higher levels of body satisfaction than younger women [31]. Although this may appear contradictory, it is possible that cognitive strategies in these older women protect their self-concept and self-esteem from the influence of body dissatisfaction [32]. Given these data, it can be hypothesized that if females in the open group had been younger, their body image scores would have been lower. The difference in body image between the two approaches then would be even more evident.

Another potential confounding factor could be a difference in body image before the operation. The preoperative assessment showed that this was not the case, however. The importance of an improved body image and cosmesis is further substantiated by the increasing popularity of plastic and cosmetic surgery and by the fact that almost all patients from this study treated with laparoscopic surgery would now prefer the laparoscopic approach if they had the choice, even if they had to pay a personal fee. The majority of the patients who underwent the operation by an open approach would choose laparoscopy as well.

The fact that patients in both groups rated the photographs of the cosmetic result for the alternative procedure comparable with the personal ratings indicates that the photographs were representative. The decreased satisfaction of patients with their own scar after seeing the cosmetically superior results of the laparoscopic approach was expected in the open group. This decrease was not significant. These patients might have been influenced in their acceptance by the open approach they had. Conversely, it could be expected that the patients in the laparoscopic group would be more satisfied with their own cosmetic result after seeing the cosmetically inferior results of the open approach. This was not the case, however. Possibly, there was a ceiling effect, which means that the superior cosmetic result of the laparoscopic approach was the reference in these patients beforehand.

It could be debated whether the advantage of an improved cosmesis and body image outweigh the longer operating times and higher costs. After all, QOL after ORP is excellent even without the superior body image and cosmesis of a laparoscopic approach. Nonetheless, the QOL questionnaires including the SF-36 do not cover body image and cosmesis after surgery. Given the findings of the current study, the clinician could decide to offer the laparoscopic approach particularly to female patients.

The current study has shown that 1 year after surgery, the QOL and functional outcome results after LRP and ORP are comparable. During a median follow-up period of almost 3 years, morbidity in terms of small bowel obstruction and incisional hernia is comparable.

The most important finding of this study is that LRP results in a superior body image and cosmesis, especially for women. Particularly for female patients, a laparoscopic approach may be considered the procedure of choice.

References

Bemelman WA, Slors JF, Dunker MS, van Hogezand RA, van Deventer SJ, Ringers J, Griffioen G, Gouma DJ (2000) Laparoscopic-assisted vs open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: a comparative study. Surg Endosc 14: 721–725

Benoist S, Panis Y, Beaufour A, Bouhnik Y, Matuchansky C, Valleur P (2003) Laparoscopic ileocecal resection in Crohn’s disease: a case-matched comparison with open resection. Surg Endosc 17: 814–818

Duepree HJ, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Brady KM, Fazio VW (2002) Advantages of laparoscopic resection for ileocecal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 45: 605–610

Milsom JW, Hammerhofer KA, Bohm B, Marcello P, Elson P, Fazio VW (2001) Prospective, randomized trial comparing laparoscopic vs conventional surgery for refractory ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 44: 1–8

Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Cuesta MA., Gouma DJ, van Deventer SJ, van Bodegraven AA, Bemelman WA (2004) Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 240: 984–991

Kienle P, Z’graggen K, Schmidt J, Benner A., Weitz J, Buchler MW (2005) Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 92: 88–93

Marcello PW, Milsom JW, Wong SK, Hammerhofer KA, Goormastic M, Church JM, Fazio VW (2000) Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: case-matched comparative study with open restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 43: 604–608

Dunker MS, Bemelman WA, Slors JF, van Duijvendijk P, Gouma DJ (2001) Functional outcome, quality of life, body image, and cosmesis in patients after laparoscopic-assisted and conventional restorative proctocolectomy: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum 44: 1800–1807

Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK (1995) Ileal pouch–anal anastomoses complications and function in 1,005 patients. Ann Surg 222: 120–127

MacLean AR, Cohen Z, MacRae HM, O'Connor BI, Mukraj D, Kennedy ED, Parkes R, McLeod RS (2002) Risk of small bowel obstruction after the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Ann Surg 235: 200–206

Nyam DC, Brillant PT, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG (1997) Ileal pouch–anal canal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis: early and late results. Ann Surg 226: 514–519

Casillas S, Delaney CP (2005) Laparoscopic surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Surg 22: 135–142

Hasegawa H, Watanabe M, Baba H, Nishibori H, Kitajima M (2002) Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy for patients with ulcerative colitis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 12: 403–406

Sardinha TC, Wexner SD (1998) Laparoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease: pros and cons. World J Surg 22: 370–374

van Duyvendijk P, Slors JF, Taat CW, Oosterveld P, Vasen HF (1999) Functional outcome after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis compared with proctocolectomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Ann Surg 230: 648–654

Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, Sprangers MA., te VA, Verrips E(1998) Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 51: 1055–1068

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H (1995) Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation, and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 82: 216–222

Morrison TG, Kalin R, Morrison MA (2004) Body image evaluation and body image investment among adolescents: a test of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence 39: 571–592

Dunker MS, Stiggelbout AM, van Hogezand RA, Ringers J, Griffioen G, Bemelman WA (1998) Cosmesis and body image after laparoscopic-assisted and open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease. Surg Endosc 12: 1334–1340

Carmon E, Keidar A, Ravid A, Goldman G, Rabau M (2003) The correlation between quality of life and functional outcome in ulcerative colitis patients after proctocolectomy ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis 5: 228–232

Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Hammel J, Church JM, Hull TL, Senagore AJ, Strong SA, Lavery IC . (2003) Prospective age-related analysis of surgical results, functional outcome, and quality of life after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Ann Surg 238: 221–228

Fazio VW, O’Riordain MG, Lavery IC, Church JM, Lau P, Strong SA., Hull T (1999) Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg 230: 575–584

Galandiuk S, Pemberton JH, Tsao J, Ilstrup DM, Wolff BG (1991) Delayed ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: complications and functional results. Dis Colon Rectum 34: 755–758

Marcello PW, Roberts PL, Schoetz DJ Jr, Coller JA, Murray JJ, Eidenheimer MC (1993) Obstruction after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: a preventable complication? Dis Colon Rectum 36: 1105–1111

Gutt CN, Oniu T, Schemmer P, Mehrabi A, Buchler MW (2004) Fewer adhesions induced by laparoscopic surgery? Surg Endosc 18: 898–906

Francois Y, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Beart RW Jr., Wolff BG, Pemberton JH, Ilstrup DM (1989) Small intestinal obstruction complicating ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Ann Surg 209: 46–50

Vasilevsky CA, Rothenberger DA, Goldberg SM (1987) The S ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. World J Surg 11: 742–750

Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, Davies M, Piotrowicz K, Barner SA, Wolff B, Pemberton J (2006) Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg 243: 667–670

Demarest J, Langer E (1996) Perception of body shape by underweight average, and overweight men and women. Percept Mot Skills 83: 569–570

Lokken K, Ferraro FR, Kirchner T, Bowling M (2003) Gender differences in body size dissatisfaction among individuals with low, medium, or high levels of body focus. J Gen Psychol 130: 305–310

Franzoi SL, Koehler V (1998) Age and gender differences in body attitudes: a comparison of young and elderly adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev 47: 1–10

Webster J, Tiggemann M (2003) The relationship between women’s body satisfaction and self-image across the life span: the role of cognitive control. J Genet Psychol 164: 241–252

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Polle, S.W., Dunker, M.S., Slors, J.F.M. et al. Body image, cosmesis, quality of life, and functional outcome of hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy: long-term results of a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 21, 1301–1307 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-007-9294-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-007-9294-9