Abstract

The name peperino derives from the Italian word pepe (from the Latin word piper, pepper) and has been used in the common language for lithified volcanic deposits characterized by light grey through dark grey tones and granular textures, resembling that of ground pepper. Among these, the best-known examples are represented by some phreatomagmatic deposits of the Colli Albani Volcanic District, near Rome (Italy), and ignimbrite deposits of the Cimini Mountains near Viterbo (Northern Latium, Italy), which have been widely employed in artefacts of historical and archaeological interest. In particular, these resistant volcanic rocks have been widely employed by the Etruscans and Romans since the seventh century BCE to produce sarcophagi and dimension stones, as well as architectural and ornamental elements. These rocks are still in use for building ornaments, street furniture and artworks in central Italy today. In this review, we provide an overview of the use of this term, and an exhaustive review of the different rocks of central Italy defined as peperino, describing their distinctive textural features, as well as their eruptive sources and outcrop areas. Indeed, despite the common macroscopic aspect, peperino rocks can be associated with several different eruptive styles and emplacement mechanisms. Our review is also addressed to archaeologists concerned with restoration initiatives and provenance studies, as well as to volcanologists studying the genetic processes of pyroclastic rocks and related naming conventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term peperino (from the Latin root piper, pepper) was originally established in Italy to define peculiar light porous volcanic rocks with a granular texture (resembling ground pepper), used as construction stones since pre-Roman times. Generally speaking, peperino is a kind of “diamictite” (sensu Flint et al. 1960), that is a lithified, poorly sorted, deposit consisting of “floating” clasts suspended in a fine-grained matrix (Menzies 2009). According to the Penguin Dictionary of Geology (1972), peperino is defined as: “A rock of mixed pyroclastic and sedimentary origin, including pyroclastic material, and weathered and eroded volcanic material (including scoriae, cinders, etc.) cemented together”. In the Oxford Dictionary (1982) peperino is defined as: “n. light porous (usu. Brown) volcanic rock formed of small grains of sand, cinders, etc.”. The French dictionary Le Petit Robert suggests the date of 1694 for the arrival of the word péperin in the French language to refer to a volcanic tuff employed as construction stone in the Roman region. However, Scrope (1827) extended the use of the term peperino to describe clastic rocks from Limagne, in the Auvergne region of central France, which comprise mixtures of lacustrine limestone and basalt and resemble ground pepper. Scrope (1858) interpreted them as having originated by a “violent and intimate union of volcanic fragmentary matter with limestone while yet in a soft state”. To refer to the rocks from this type locality, the term peperino then shifted to peperite, which is now commonly used for clastic rocks comprising both igneous and sedimentary components, which were generated by essentially in-place disintegration and active mixing of intrusive magma, lava flows or hot volcaniclastic deposits with unconsolidated, typically wet sediments (Skilling et al. 2002; Sigurdsson et al. 2015).

The term peperino (sometimes also reported as piperino) has been used as a rock descriptor in the international geologic literature and volcanology textbooks (e.g. Rittmann 1967; MacDonald 1972; Kilburn and McGuire 2001). Other major textbooks usually describe peperites, yet seldom mention peperino. For example, Cas and Wright (1988) mention peperino in their chapter 4 on volcaniclastic deposits, while Fisher and Schmincke (1984) refer only to the piperno (another rock term derived from peperino, see below) from the Phlegraean Fields type locality, near Naples, as an example of welded fallout tuff (agglutinate). However, since its early definition, the term peperino has been applied to a variety of volcanic products that, beyond a generic common aspect, derived from quite different genetic processes. Given the widespread use of the term peperino, yet broad sense of its definition, we here complete a full review of the origin and development of the term. We also describe the lithofacies sub-types, as well as the source conditions, compositions and eruption types to which the rock can relate.

Establishment of the term peperino in Italy

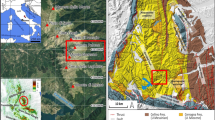

In the Italian geologic literature, the term peperino has been applied in referring to several different volcanic rocks of the Latium region of central Italy (Fig. 1) that share similar appearance, as well as similar textural and mechanical features (see Farr et al. 2015). For the most part, they are represented by either phreatomagmatic deposits of the Colli Albani Volcanic District, near Rome, or ignimbrite deposits of the Cimini Mountains near Viterbo (Northern Latium) (Fig. 1). The name peperino derives from the Italian word pepe (pepper), and has been used in the common language since the seventh century BCE, for rocks used to produce sarcophagi and as building stones (Jackson et al. 2005; Jackson and Marra 2006; Farr et al. 2015; Diffendale et al. 2018). They are still used as architectural and ornamental elements today. Indeed, these rocks are characterized by a speckled light grey to dark grey tone and granular texture, resembling that of ground pepper. The same Latin root, piper, is at the base of the local name Piperno (Breislak 1786) for a genetically distinct volcanic rock from the Phlegraean Fields, near Naples, which is a welded lithofacies of the Campanian Ignimbrite (Fedele et al. 2008).

Satellite image of central Italy showing location of the high-potassic volcanic districts of the Roman and Campanian Provinces, the calc-alkaline districts of Cimini and Ceriti Mts., and of the sites mentioned in the text. Inset shows a detail DEM of the Colli Albani region, where the ancient Roman quarries of peperino (Lapis albanus and Lapis gabinus) were located

The ancient Romans used the word lapis (stone) for the peperino rocks, as well as for all the hard rocks, either volcanic or sedimentary, employed as dimension stones in building construction. In particular, the two types of rock cropping out in the surroundings of Rome that are today referred to as peperino, i.e. the Peperino di Marino (or Peperino albano) and the Peperino di Gabii, were called Lapis albanus (Vitruvius, De Architectura, 2.7) and Lapis gabinus (Strabo, Geography, 5.3.10; Tacitus, Annales, 15.43), respectively, by the ancient Romans.

Here, we present an overview of the origin of the term peperino and its use, in both the common and scientific language, as based on an extensive bibliographic search, given as Supplementary Material #1. The original language versions of the definitions, translated herein into English, are also given in Supplementary Material #1. Moreover, we provide a complete review of the rocks of Latium that have been named peperino in the scientific literature, describing their textural aspects, their eruptive centres, areal distributions and type localities. While the family tree for the development and application of the term peperino is given in Fig. 2, examples of peperino rocks are given in Figs. 3 and 4. This sets the guidelines for unambiguous distinction of peperino types and related source areas.

Detail of a block of the Subura wall in Rome (Forum of Augustus, first century BCE) showing the macroscopic textural and compositional features of Lapis albanus. 1 = lighter, olive-grey glass matrix (with zeolite cement), 2 = numerous lava rock fragments, 3 = leucite and analcime crystal fragments (hexagonal shapes), 4 = biotite (black mica) crystal fragments, 5 = limestone rock fragments; smooth, fairly durable stone surface

Macroscopic aspects of the Rome's peperino rocks. a) Peperino albano (Lapis albanus): 2nd Eruptive Cycle—Unit e (36 ± 1 ka) of Albano Crater. b) Peperino di Gabii (Lapis gabinus): phreatomagmatic unit (ca. 285 ka) from Castiglione Crater. c) Peperino grigio: Palatino Eruption Unit (533 ± 2 ka) from Colli Albani Volcanic District. d) Peperino della Via Flaminia: Palatino Eruption Unit (534 ± 2 ka) from Colli Albani Volcanic District

Early definition of peperino rocks

The first attested use of the word peperino in the scientific literature seems to be in an essay by the Swedish mineralogist Johan Gottschalk Wallerius, as reported by Desmarest (1765) (for this and the following citations, see also Online Resource 1 for extended text). Desmarest (1765), however, argued against the similarity with the Tiburtine rock (i.e. the travertine from Tivoli near Rome) proposed by Wallerius, going on to describe pépérine as.

"a compound stone, which is based on a terracotta, which envelops materials altered or not altered by fire; this cooked paste, of a whitish or reddish gray, is more or less friable. There are, mixed in different proportions, scoriaceous and melted materials, a few blades of glass, mica, gabbro or schorl, pieces of limestone, quartz, etc".

Desmarest (1773) then used the same term for the volcanic rocks into which the cellars of the French city of Clermont-Ferrand, in the region of the Chaine des Puys and Limagne graben (Auvergne), were excavated:

"(…) The hill where the city is built, is composed of similar dense lava beds and of pépérine, comprising whitish material, pulverulent or solid, as small red spots or hazy tracks, as well as big pieces of limestones with their original grain. (…)".

Today this hill is known to be part of a maar rim on which the cathedral of Clermont-Ferrand stands (Boivin et al. 2015). Several decades later, Scrope (1825, 1827) used peperino for an ensemble of rocks occurring in the Auvergne:

“In giving the name of peperino to a volcanic conglomerate consisting of fragments of basalt and scoriæ, without pumice, tufa, or any trachytic matter, united either by simple adhesion or a calcareous or argillaceous cement, I follow the Italian geologists, who have continued this trivial term to a similar rock, which also, like that under consideration, occasionally contains fragments of limestone and primitive rocks, bituminized wood, &c., &c.-Vid. Brocchi Catalogo ragionato di Rocce, pp. 45, 47”.

Ten years previously, the French naturalist Cordier (1815) had used the term Pépérite to identify tuffs. Originally, the term pépérite was thus closely related to the term peperino as used by the Italian geologists and archaeologists. For some time, the two terms were used as synonyms by French geologists and applied to special types of volcanic tuffs and breccias found in the Limagne (Guérin 1839).

Since the nineteenth century, the term pépérite has suffered a strong “semantical drift” (De Goër De Herve 2000), being extended to other kinds of rocks produced by a wide range of geological processes, and not exclusively those connected to volcanism. The French pépèrites represent a standalone group of rocks and are not the subject of this review. Instead, a modern volcanological description and classification of the pépérites is provided in White et al. (2000) and Skilling et al. (2002). White et al. (2000) proposed the adoption of peperite as a genetic term: “… applied to a rock formed essentially in situ by disintegration of magma intruding and mingling with consolidated or poorly consolidated, typically wet sediments”.

Breislak (1786) provided another definition of peperino as being like “a fragmented lava”, while Ferber (1776) used piperino (from the Latin root piper) to name the volcanic rock outcropping in the surroundings of the Albano and Nemi lakes (southeast of Rome, Italy). He classified the rock as tufo (tuff) and described it as "greenish-grey rusty ashes, with black sherd-lamelles, white garnet-like sherds, and small pumice-stones". Ferber (1776) also stated that "The quarries of Piperino, employed at Rome in buildings and sculpture, are near Marino", allowing us to unambiguously identify it with the Lapis albanus. Ferber (1776) also mentioned.

"Piperino or Granito di S. Fiora; a particular sort of lava, composed by a large quantity of white sherl in oblong parallelepiped crystals; much black sherl-mica, and some lava".

However, he specified:

"Properly the name of Piperino belongs only to indurated volcanic ashes or tufo with sherl-crystals; accordingly, the above-described of S. Fiora, being a lava, should not be called by that name".

Both Ferber (1776) and Breislak (1786) also discussed the similarity of the rock locally called piperno occurring at Pianura, near Naples (in the Phlegraean Fields Volcanic District, Fig. 1). This rock was extensively used since the Greek–Roman age to pave roads, and was the main building stone in the Campania region until the cessation of quarry activity at Soccavo and Pianura at the beginning of the twentieth century (Calcaterra et al. 2000, 2005). The name piperno derives from the Latin name of the Roman village Pipernus (modern Priverno, southern Latium) which, in turn, is a distortion of the Latin term piper (pepper). The local use of the word piperno can be traced to the earliest written documentation dating to 1428 CE (de' Gennaro et al. 2000; GeoPortale 2009). This rock is a proximal deposit of the Campanian Ignimbrite, the highest magnitude explosive eruption of the Mediterranean area in the last 40 ky (Fedele et al. 2008; Scarpati et al. 2020). It is exposed along the eastern sector of the caldera rim of the Phlegraean Fields and in the city of Naples (Rittmann 1950; Perrotta et al. 2006; Fedele et al. 2008; Scarpati et al. 2020) and consists of alternating beds of welded tuff with flattened scoriae (fiamme) and coarse lithic breccia with grey lava clasts (Fedele et al. 2008). Von Buch (1809) distinguished the term peperino from “tuff” as follows:

"It is easy to distinguish the peperino from the tuff. In the first almost all is fresh, perfect and without damage. In the second, all is dull, dead and destroyed [here Von Buch (1809) remarks on the relatively fresh, unaltered character of the peperino with respect to the higher degree of alteration and/or vapor-phase transformation (zeolitization) that usually affects the glass matrix of tuffs, accompanied by analcimization of leucite crystals]. The angular pieces of limestone that characterize Peperino from Mt. Albano; big basalt masses sometimes rounded, sometimes with angular boundaries suddenly appear in Peperino [here Von Buch (1809) points out the widespread occurrence of carbonate and lava lithic clasts in Peperino]".

An accurate description of the petrographic and lithologic features of the “Peperino albano” was provided in Gmelin (1814b):

"Peperino is a fragile stone, very fit to building, of an earthy texture, and not heavy. It seems to consist of a congeries of very different bodies, particularly fragments of augite of a dirty green, dark green mica, iron sand, compact limestone, basalt, and a kind of lava very resembling pumice. These seem to be agglutinated by an earthy cement. Sometimes it contains fragments of stones. These fragments are always sharp-edged, generally small, but sometimes weighing several pounds, especially those consisting of basalt and limestone. Sometimes, though rarely, fragments of feldspar, and a scoriaceous matter of a dark green color are mixed into the peperino".

Scientific classification of peperino rocks

The first classification of the peperino rock type within the volcanic petrographic nomenclature is provided by Brocchi (1817) in his "Catalogo ragionato di una raccolta di rocce per servire alla geognosia" (Geological catalogue of rocks). Brocchi (1817) classified three types of volcanic rocks: lava, tufa (tuff), and peperino. Moreover, he distinguished several lava varieties, including "lava necrolite", "lava piperno", "lava nenfro", and "lava sperone", all of which have relationships, to different degrees, with the peperino rocks. We note, though, that most of these rocks, with the exception of "lava necrolite", are not effusive products and thus do not comply with the modern definition of lava (cf. Sigurdsson et al. 2015), as discussed below.

Brocchi (1817) also distinguished two types of tuff:

"one is friable, dusty, usually yellowish in color, including variable amount of amfigena [leucite] and pirossena [pyroxen] and often lava pebbles"; "the other one is solid, hard, stony". He named the latter as "tufa pietrosa" (lithified tuff) and then he stated: "peperino is nothing but a tufa pietrosa which, apart for the color, is similar to that of the Capitoline Hill and Monteverde [i.e. Tufo lionato pyroclastic-flow deposit, see Marra et al. (2018)], but harder, and does not contain fragments of pumiceous lava [i.e. scoria clasts] since the yellowish ones are of lava sperone [see below for a description of this rock]. Amfigene crystals are mostly glassy, while in tufa they are commonly floury [i.e. turned to analcime]".

It is worth noting that the remark on the unaltered character of the peperino with respect to tufa mirrors the distinguishing criterion already outlined by von Buch (1809).

Based on the above criteria, Brocchi (1817) described several peperino rock types from different areas of central-western Italy in his rock catalogue (Table 1). All had the common characteristic of a highly heterogeneous componentry, comprising juvenile angular fragments of massive and/or vesicular lava or scoria, and wall rock fragments (roccia primitiva). In addition, free crystals and fragments of pyroxene, haüyne (lazialite), leucite (amfigena), magnetite (ferro magnetico), Ti-magnetite (ferro titanico) and brown to black mica were identified. These were found in the rock along with angular clasts of Apennine limestone, with or without tremolite, and were supported by a calcareous matrix. Due to the abundant calcite veins found in some places, Brocchi (1817) advocated an origin from underwater eruptions for the peperino rocks.

Brocchi (1817) also argued against the improper use of the term peperino when applied to the volcanic rocks cropping out near Viterbo, in the Cimini Mountains, "distinguished by the local inhabitants with the word peperino" (i.e. Peperino delle Alture Auct., Peperino tipico) (Peperino of the heights; Typical Peperino), "as it has been already adopted in books to indicate a particular variety of tuff".

Indeed, Brocchi (1817) identified these rocks from Cimini as a lava, which he named "lava necrolite" (from the Greek words necros, death, and lithos, rock), on account of the use by the Etruscans to carve their sarcophagi and excavate their burial chambers into this rock type. However, Brocchi (1817) also introduced the name "lava piperno" for the welded ignimbrite deposits cropping out in northern Latium at Ronciglione and Caprarola (part of the Vico volcano), based on the close resemblance with the piperno occurring at Pianura, near Naples, described by Breislak (1786). It is not clear whether Brocchi was aware of the fact that the terms piperno and peperino should be considered synonymous. With the definition of "lava piperno" and the statement that it is cognate to the "lava nenfro" (see below), Brocchi (1817) created the scientific basis linking all rocks included in Table 1 to the term "peperino".

Brocchi (1817) also used "lava nenfro" (from an untranslatable local word) to apply to two welded ignimbrite deposits cropping out in northern Latium, i.e. at Villa San Giovanni in Tuscia (near Blera and Vetralla) and in between Canale and Rota (Fig. 1). These rocks were exploited locally for building and sculpture stone, with Brocchi (1817) stating that "this rock is nothing but a lava that holds a middle place between the lava piperno and ordinary lava". However, these are not lavas. The first deposit (later named “peperino listato” by Sabatini 1896) is actually a welded facies of “ignimbrite B” (Locardi 1965) or “ignimbrite II trachitica” (Bertini et al. 1971) from Vico volcano. The second deposit is a valley-confined, lithified facies of the Bracciano pyroclastic flow unit of the Sabatini Volcanic District (de Rita et al. 1993), also named locally as peperino (Bertini et al. 1971).

The term nenfro is also used locally in the Vulsini Volcanic District (southern Tuscany–northern Latium; Fig. 1). Moderni (1903) first used nenfro to name welded ignimbrites characterized by the occurrence of flattened black pumices (fiamme) in a dark grey to reddish-purplish, strongly lithified ash matrix (Alberti et al. 1970; Nappi and Marini 1986). These deposits were emplaced during the Paleovulsini activity at ca. 0.6–0.5 Ma (Vezzoli et al. 1987; Palladino et al. 2010).

Finally, Brocchi (1817) defined "lava sperone" as an intermediate rock type between compact and porous lava. This term was introduced by Gmelin (1814) after the local name for the welded scoria lapilli fall deposits (from Strombolian activity) exploited around the Tuscolo archaeological site along the Tuscolano-Artemisio caldera rim of Colli Albani. The term "sperone" (spur) has been erroneously reported by Lugli (1957) as an archaeological name for the Lapis gabinus, probably because of a faint resemblance between these genetically and petrographically different rocks (Farr et al. 2015).

In Table 1, we report all peperino rock types listed by Brocchi (1817), with the identification of the corresponding stratigraphic units from the modern geological literature. Besides the canonical Lapis gabinus and Lapis albanus, which correspond to the phreatomagmatic deposits of the Castiglione maar and of the Albano multiple maar (second eruptive cycle), respectively, Brocchi (1817) lists a number of other peperino rocks. These include pyroclastic deposits of the Albano (first eruptive cycle) and Nemi multiple maars (Colli Albani), as well as of the Tomacella eruptive centre, located near Frosinone (central-southern Latium) in the Volsci Volcanic Field (Cardello et al. 2020; Marra et al. 2021). These rocks all have a common phreatomagmatic origin and similar field appearance. For example, they are all characterized by carbonate and lava clasts in a lithified grey ash matrix containing loose clinopyroxene, dark mica, leucite and/or feldspar crystals.

In addition, Brocchi (1817) classified as peperino some distal occurrences of the pyroclastic-flow deposits of the Tufo del Palatino to the east of Rome (Table 1). In the same way, the popular definition of peperino was attributed to the same unit in the central and northern sectors of Rome (i.e.”Peperino della Via Flaminia”,”Peperino grigio”; see sheet 149—Roma of the geological map of Italy; Table 2).

Brocchi (1817) rejected the use of the term peperino for other volcanic rocks of northern Latium, which instead he considered as different varieties of lava, with the only exception being the deposits between Rota and Tolfa, which he termed peperino. These rocks correspond to a valley-confined, lithified facies of the Bracciano pyroclastic flow unit of the Sabatini Volcanic District (de Rita et al. 1993) and are named locally as peperino (see also Bertini et al. 1971).

Following the acceptance by the scientific community of the classification proposed by Brocchi (1817), the term peperino was subsequently used to describe volcanoclastic rocks outside of Italy. Scrope (1825), for example, proposed the term "calcareous peperino" to label the characteristic alternations of beds of carbonates with those containing abundant volcanic fragments (see above) as occurring at the Gergovie plateau (Auvergne, France; also cf: Chazot and Mergoil-Daniel 2012). Scrope (1825) also used "calcareous and conchiferous Peperinos" for similar sedimentary successions of Veneto (i.e. Veronese, Vicentino, and Euganean hills; northern Italy) and southern Sicily.

Roth (1887) also reported:

"the local name of the tuff of the Albano Mountains, Peperin (where the pieces of black leucitophire emerge as peppercorns from the lighter soil mass), has sometimes been transferred to other tuffs without connecting them with a well-defined term. Boricky (1873–74, p. 42; Kostenblatt, now Kostomlaty) called the basaltic tuff of Bohemia, which he regards as hardened lava, a "peperitic basalt".

More than one century later, Le Maitre (2002) reviewed the term “peperin-basalt”, describing it as "an obsolete name for a tuff which forms mud flows and contains large crystals of augite and hornblende".

However, apart from some sporadic uses outside of Italy, such as those mentioned above, until the end of the nineteenth century the term peperino remained generally a name used in the volcanic areas of Colli Albani, Sabatini and Cimini-Vico. The diffusion of this term to the Roccamonfina and Vulsini volcanoes was proposed by Moderni (1904), who aimed to.

"demonstrate that the origin of this tuff, so widely represented among the materials of the Tyrrhenian volcanoes, can be as different as its position is different in different locations".

In particular, with respect to the "position" of the peperino, Moderni (1904) referred to its proximal (near-vent) versus distal occurrence:

"In the Sabatini Volcanoes this tuff is not part of the materials that ordinarily constitute the cones, but it is found stratified more or less horizontally always at a certain distance from the eruptive centers: in the Roccamonfina Volcano and in the Vulsini Volcanoes, it also contributes to forming the skeleton of the cones".

Moderni (1904) stated that:

"The peperino of Montefiascone is very different from that of Cimini Mounts and that of Latium; of ash gray or iron gray color, consists of volcanic sands at times very fine but more often coarse, and contains fragments of lava, pieces of scoria, lapilli, crystals of augite, leucite and other volcanic minerals embedded in the tufaceous paste fragments of Eocene rocks."… "The whole large cone of Montefiascone... is mainly made up of this rock".

The Montefiascone peperino actually consists of distinct eruptive products, including the Ignimbrite Basale di Montefiascone (WIM, Tuscania and Viterbo sheets of the 1:50.000 geologic map of Italy, CARG project) and the Formazione de La Berlina (WBE; previously known as Ignimbrite di Montefiascone; Vernia et al. 1995).

In addition, Moderni (1904) described three peperino occurrences near Valentano village, in the area of the Latera caldera (western Vulsini). These are characterized by a grey tone and contain yellowish scoria clasts, lava and limestone lithics. Abundant small leucite, augite and mica crystals are also present. These deposits possibly correspond to a lithified facies of the Tufi di Poggio Pinzo phreatomagmatic-Strombolian succession (Vezzoli et al. 1987; Palladino and Simei 2005).

It was mainly in the twentieth century, the term peperino entered in the official geologic literature as an informal name for a number of pyroclastic deposits (Fig. 2). In Table 2a–d, we list all stratigraphic units for which the local definitions of peperino (or, in a few cases, piperno) have been reported in the 1:100.000 geological mapping completed by the Servizio Geologico d'Italia (Geologic Survey of Italy). The term was also endorsed by two volcanological studies for the Latium region in the 1960s (Fornaseri et al. 1963; Mattias and Ventriglia 1970).

Following Mattias and Ventriglia (1970), the geological map of the Sabatini Volcanic District (de Rita et al. 1993) then also used the piperno di Mazzano label for a welded facies locally found in the lower part of the Tufo Rosso a Scorie Nere. This unit is distinct from the peperini listati, which represent deposits from an earlier eruptive event in the western Sabatini (see also Cioni et al. 1993).

Eruptive and emplacement processes of peperino rocks

The term peperino and its derivation piperno have been used in reference to a variety of volcanic rocks that differ in terms of their formative eruptive and emplacement mechanisms, source areas and ages. With the exception of the Peperino delle Alture, which is a lava rock type related to the effusive activity of the Cimini Mountains dome complex, all the other cases of application are for rocks derived from the products of explosive eruptions with different styles and magnitudes (Table 3). There are three cases of peperino application when assessed by eruption style and magnitude:

-

i)

for rock types derived from small-scale (< 1km3) phreatomagmatic eruptions. These rocks mainly represent the proximal facies of base surge deposits and are usually lithified, massive to faintly stratified, and rich in aquifer lithics. They can be related to maar–tuff rings, as for the “Peperino di Gabii” from the Castiglione maar in the Colli Albani (Marra et al. 2003), to small caldera systems, as is the case for the peperino examples from Baccano and Montefiascone, or to carbonate-seated maar–diatremes, as in the examples from the Volsci Volcanic Field (Cardello et al. 2020; Marra et al. 2021). In other cases, peperino rocks are related to massive, thickened facies of phreatomagmatic pyroclastic currents locally channelized in topographic lows, as is the case for the “Peperino albano” at the type locality of the Marino quarries (Giordano et al. 2002; Freda et al. 2006);

-

ii)

for rocks resulting from the emplacement of widespread (1–10 km3) ash-rich, accretionary lapilli-bearing, “wet” pyroclastic currents. This applies to, for example, the Tufo del Palatino, resulting from a large-scale explosive event with a significant hydromagmatic component during the early activity of Colli Albani (Marra and Rosa 1995; Karner et al. 2001a; Palladino et al. 2001);

-

iii)

for rocks consisting of fiamme-bearing, welded pyroclastic deposits from magmatic hot pyroclastic currents. These can be associated with small-scale lava dome collapse, as is the case for the “Peperino Tipico” from the Cimini Mountains (Cimarelli and de Rita 2006) or with moderate- to large-scale (1–100 km3) caldera-forming events, which include the peperino and piperno examples from Vico, Sabatini and the Phlegraean Fields (Table 3).

The application of the peperino term also spans a range of compositions. While all cases from i) and ii) were fed by mafic ultrapotassic magmas of the Roman Province (Freda et al. 2006; Marra et al. 2009, 2021), the “Peperino Tipico” example is part of the Pliocene–Lower Pleistocene silicic magmatism of Tuscany and northern Latium. However, the other cases from iii) resulted from the eruption of phonolites and trachytes associated with the potassic magmatism of the Roman (Vico, Sabatini) and Campanian (Phlegraean Fields) provinces (Fedele et al. 2008; Palladino et al. 2014).

The use of peperino rocks in Roman and Etruscan monuments

In the City of Rome, systematic quarrying of Tufo del Palatino for dimension stone (i.e. a natural rock that has been selected and finished to specific sizes or shapes) began in the archaic period (8th–third century BCE; Lanciani 1897; Coarelli 1974; Lugli 1957; Cifani 1994). However, the designation of peperino for the Tufo del Palatino (commonly known as “Cappellaccio”) has been used only in a few scientific publications (e.g. "peperino grigio", sheet 149—Roma of the geological map of Italy; Ventriglia 1971). The Tufo del Palatino is typically affected by pronounced and rapid weathering due to its relative softness and pervasive cleavage. For this reason, its use as building material ceased at the beginning of the fourth century BCE, when improved quarrying techniques and access to deposits further from Rome allowed the exploitation of more durable rocks. The two peperino rocks, Lapis albanus and Lapis gabinus, are characterized by higher uniaxial compressive strength than all other tuffs from the Colli Albani and Sabatini volcanic districts. As a result, they are less prone to weathering. This favoured their widespread employment in architectural elements that are subject to high pressures, such as piers, weight-bearing walls, and arches (Jackson and Marra 2006). According to Tacitus (Annales, 15, 43), Emperor Nero promulgated an edict that ordered the use of Lapis albanus and Lapis gabinus in the reconstruction of the basements and ground floors of buildings destroyed by the 64 CE great fire of Rome, the reason being that these rocks were reputed as fire-proof. Such a notion must have been retained from earlier times, since Augustus built the retaining wall of his Forum with these two rocks so as to protect it from the devastating fires that frequently occurred in the nearby Subura quarter (Figs. 5 and 6). These rocks were also used to construct the Tabularium in 78 BCE, which hosted the state archive (Lugli 1957). Lapis gabinus was also systematically used for the pillars and arches of ancient bridges and aqueducts (Lugli 1957). A full chronology of the principal Roman monuments in which the two peperino stones (Lapis albanus and Lapis gabinus) have been employed is summarized in Table 4. Here we complete a short review as to how three types of peperino (Lapis albanus, Lapis gabinus and Peperino di Viterbo) became historically and archaeologically important by being used in the construction of ancient monuments in Rome and Latium. This is also relevant for interdisciplinary research in geo-archaeology and cultural heritage dealing with provenance studies and restoration interventions.

The Peperino di Viterbo is a grey, porphyritic rock derived from both quartz-latitic domes (Peperino delle Alture) and associated ignimbrites (Peperino tipico) of the Cimini volcanoes. a) Section normal to depositional surface: welded pyroclastic flow deposit showing light-coloured, iso-oriented, flattened pumice clasts (fiamme); b) same, section parallel to depositional surface showing sanidine-rich fiamme with dark rims and various lithic inclusions

Lapis albanus

Lugli (1957) and Holloway (1994) proposed that Lapis albanus began to be used as building material in the third century BCE. However, recent geochemical analysis from the Sant’Omobono Sacred Area demonstrated that this date should be moved back to the early fifth century BCE (Diffendale et al. 2018; Farr et al. 2015). In fact, Lapis albanus occurs in the facing of the first‐phase (fifth century BCE) platform supporting the twin temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta and in part of the eastern edge of the platform at its southern end. The use of Lapis albanus was confirmed for several monuments within the temple platform, spanning the 4th through third centuries BCE (Diffendale et al. 2018). Moreover, Karner et al. (2001b) suggested an early use (fifth century BCE) of Lapis albanus for the Tullianum. Lapis albanus was also extensively used as the base for inscriptions carved in stone, since the oldest known example for Consul Appius in 264 BCE (Torelli 1968) through the first century BCE. Since the mid-third century through the end of the second century BCE, Lapis albanus was systematically used to produce the sarcophagi of Scipions' sepulchre, and was used in construction of several tombs and villas built along the Via Appia in the second and first centuries BCE (Lugli 1957). It was largely used during the late Republican and the early Imperial age in several buildings and temples (Table 4). Lapis albanus was used during the mid-second century CE in the construction of Adrian's temple and mausoleum, the temple of Antoninus and Faustina. Its employment was, however, abandoned towards the end of the second century, its last use being attested in the year 202 CE at the permanent legionary fortress of Castra Albana, close to the original quarrying site at Alba (Lugli 1957).

Lapis gabinus

In the site of Gabii, located on the rim of the Castiglione maar (Fig. 1), the local deposit (Peperino di Gabii or Lapis gabinus) was exploited since at least the tenth century BCE to produce blocks employed in the construction of walls and long after the Roman conquest in 493 BCE. In the late Republican period, the town of Gabii was depopulated due to the extensive quarrying activity of the Lapis gabinus. According to Lugli (1957), the earliest use of Lapis gabinus in Rome was in the arches of the Acqua Marcia aqueduct in 144 BCE. However, Farr et al. (2015) identified the occurrence of Lapis gabinus blocks in a small staircase abutting the fifth century BCE main podium of the twin temples at Sant'Omobono, although it was probably added in a later period. Probably due to the greater distance from Rome to the quarry site, with respect to that of the Lapis albanus, the Lapis gabinus was employed to a lesser extent in the City (Table 4). The most prominent buildings in which it occurs are the state archives (Tabularium), and the Forums of Caesar and Augustus.

Peperino di Viterbo

The Peperino di Viterbo (also known as “Peperino Tipico”) in northern Latium was used as a building material, as early as the Palaeolithic age, as a substrate for rock sculptures In addition, there are rock tombs with monumental altars documented in central-southern Etruria and dated between the sixth and third centuries BCE (Bianchi et al. 1963). Peperino di Viterbo (although often reported as “nenfro” in archaeological texts) was also used in a large number of Etruscan sarcophagi (e.g. from the burial chambers of Tarquinia and Tuscania) between the seventh and first centuries BCE, as well as sculptures mainly representing fantastic animals (Bianchi et al. 1963). Lugli (1957) reported erroneously the occurrence of the Peperino di Viterbo in ancient Rome, in the “portichetto" at Foro Olitorio (actually made up of an intrusive rock).

Conclusions

The term peperino was originally used for volcanic rocks of grey tone and granular texture, with resemblance to ground pepper, derived from phreatomagmatic eruptions of Colli Albani (i.e. Peperino di Marino, Peperino di Gabii). However, the term peperino (with the piperno variety) was extended to other volcanic rocks of central Italy that span a range of magma compositions, eruption styles and magnitudes. Peperino examples are mainly related to the potassic and ultrapotassic magmatism of the Roman and Campanian provinces (Middle to Upper Pleistocene), with mafic (K-foidites) to differentiated (trachites and phonolites) compositions, with a few exceptions related to silicic magmatism of Pliocene-Lower Pleistocene (e.g. Peperino di Viterbo from the Cimini Mountains). With one exception, peperino rocks are related to explosive eruptions ranging from small-scale phreatomagmatic events associated with diatremes, maars and tuff rings to moderate to large pyroclastic currents associated with major caldera-forming events (Table 3).

The different magma compositions, eruptive styles and geological settings with which peperino rocks are associated result in a range of componentry. The unifying features of all peperino rocks are the grey tone, the granular appearance, and the lithified ash matrix. However, the juvenile components may vary from dark, poorly vesicular scoria in phreatomagmatic cases to flattened scoria or pumice (fiamme) in welded ignimbrite cases. Early authors, such as Gmelin (1814) and Brocchi (1817), also pointed to the characteristic occurrence of both black (accessory lava) and white (accidental limestone) lithic clasts in some peperino examples (e.g. Peperino di Marino).

Peperino stones play a major role in the history of construction, sculpture and archaeology, yet the term lacks a rigorous geologic definition. Peperino can only be used informally as a generic, purely descriptive term, which cannot be related to a specific composition or volcanic process. In this regard, attempts to use its offshoot term, peperite, remain ambiguous and lack general consensus among geologists.

The reference peperino examples from central Italy volcanoes may be useful for comparison with similar rock types that are common in volcanic environments worldwide. However, we do not claim for a broad use of the term in place of, or in addition to, the existing well-established terminology for volcanic lithofacies. We suggest that peperino can be used mainly in geo-archaeological and cultural heritage contexts to describe a light, porous, poorly sorted pyroclastic rock consisting of lapilli-sized juvenile and accessory and accidental lithic clasts, supported in a lithified ash matrix typically grey in tone. Detailed textural and compositional characterization may allow identification of a specific peperino type and its source area, relevant for provenance studies and restoration interventions.

References

Alberti A, Bertini M, Del Bono GL, Nappi G, Salvati L (1970) Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1:100.000 – Foglio 136 Tuscania, Foglio 142 Civitavecchia, Servizio Geologico d’Italia

Barberi F, Buonasorte G, Cioni R, Fiordelisi A, Foresi L, Iaccarino S, Laurenzi MA, Sbrana A, Vernia L, Villa IM (1994) Plio-Pleistocene geological evolution of the geothermal area of Tuscany and Latium. Mem Descr Carta Geol Ital 49:77–134

Bertini M., D’Amico C., Deriu M., Tagliavini S., Vernia L. (1971). Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1:100.000 – Foglio 143 Bracciano, Servizio Geologico d’Italia

Bianchi Bandinelli R, Peroni R, Colonna G (1963) Arte etrusca e arte italica Ed. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Roma, 61p

Boivin P, Miallier D, Cluzel N, Devidal J-L, Dousteyssier B (2015) Building and ornamental use of trachyte in the center of France during antiquity: Sources and criteria of identification. J Archaeol Sci Rep 3:247–256

Borický E (1873–74) Petrographische Studien an den Basaltgesteinen Böhmens. Archiv für der naturwissenschaftliche Landesdurch-forschung von Böhmen, vols. ii. and iii, pp. 294. Cambridge University Press: Geological Magazine , Volume 3 , Issue 1 , January 1876 , pp. 35 - 38. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800153932

Breislak S (1786) Saggio di osservazioni mineralogiche sulla Tolfa, Oriolo, e Latera di Scipione Breislak delle Scuole Pie lettore di filosofia nel Collegio Nazareno dedicato a sua eccellenza reverendissima monsignor Onorato Gaetani de' duchi di Sermoneta. Roma, Stamperia Giovanni Zempel

Brocchi G (1817) Cattalogo ragionato di una raccolta di rocce disposto con ordine geográfico per servire alla geognosia dell’Italia. Dall’Imperiale Regia Stamperia. Milano

von Buch L (1809) Geognostische Beobachtungen auf Reisen durch Deutschland und Italien angestellt von Leopold von Buch. Berlin, Haude und Spener. Zweiter Band

Calcaterra D, Cappelletti P, Langella A, Morra V, Colella A, de Gennaro R (2000) The building stones of the ancient centre of Naples (Italy): Piperno from Campi Flegrei. A contribution to the knowledge of a long-time-used stone. J Cult Herit 1(4):415–427

Calcaterra D, Langella A, de Gennaro R, de’Gennaro M, Cappelletti P (2005) Piperno from Campi Flegrei: a relevant stone in the historical and monumental heritage of Naples (Italy). Environ Geol 47:341–352

Campobasso C, Cioni R, Salvati L, Sbrana A (1994) Geology and paleogeographic evolution of a peripheral sector of the Vico and Sabatini volcanic complex, between Civita Castellana and Mazzano Romano (Latium, Italy). Mem Descr Carta Geol Ital 49:277–290

Capaccioni B, Nappi G, Valentini L (2001) Directional fabric measurements: An investigative approach to transport and depositional mechanisms in pyroclastic flows. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 107:275–292

Cardello GL, Consorti L, Palladino DM, Carminati E, Carlini M, Doglioni C (2020) Tectonically controlled carbonate-seated maar-diatreme volcanoes: the case of the Volsci Volcanic Field, central Italy. J Geodyn 139:106904

Cas RAF, Wright JV (1988) Volcanic successions modern and ancient. Springer, Dordrecht, XVI+528p

Chazot G, Mergoil-Daniel J (2012) Co-eruption of carbonate and silicate magmas during volcanism in the Limagne graben (French Massif Central). Lithos 154:130–146

Cifani G (1994) Aspetti dell’edilizia romana arcaica. Studi Etruschi 60:185–226

Cimarelli C, de Rita D (2006) Structural evolution of the Pleistocene Cimini trachytic volcanic complex (Central Italy). Bull Volcanol 68:538–548

Cioni R, Laurenzi MA, Sbrana A, Villa IM (1993) 40Ar/39Ar chronostratigraphy of the initial activity in the Sabatini volcanic complex (Italy). Boll Soc Geol Ital 112:251–263

Coarelli F (1974) Guida Archeologica di Roma. Mondadori, Milan, p 357

Cordier L (1815) Mémoire sur les substances minerals dites en masse, qui entrent dans la composition des roches volcaniques. Imp. Mme Ve Courcier, 96p

De Goër De Herve A (2000) Peperites from the Limagne trench (Auvergne, French Massif Central: A distinctive facies of phreatomagmatic pyroclastics. History of a semantic drift. In: Leyrit H, Montenat C (eds) Volcaniclastic rocks from magmas to sediments.- Gordon & Breach Sc. Pu, 91–110

de’Gennaro M, Calcaterra D, Cappelletti P, Langella A, Morra V (2000) Building stone and related weathering in the architecture of the ancient city of Naples. J Cult Herit 1(4):399–414

Desmarest N (1765) Sur l’origine & la nature du Basalte à grandes colonnes polygones, determinées par l’Histoire Naturelle de cette pierre, observée em Auvergne. Histoire de L’Academie Royale des Sciences. Année M.DCCLXXIV, Avec les Mémoires de Mathématique & de Physique, pour la même Année, tirés des registres de cette Académie. 705–775. Paris, De L’Imprimerie Royale

Desmarest N (1773) Memoire sur le basalte. Troisième partie, où l’on traite du basalte des ancienns; & où l’on expose l’hystoire naturelle des diferentes espèces de pierres auxquelles on a donné, em differens terms, le nom de basalte. Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, 599–670. Available at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3572b/f755.item. Accessed 10 Oct 2020

Diffendale D, Marra F, Gaeta M, Terrenato N (2018) Early use of Anio tuff and Lapis Albanus in the Roman temples at Sant’Omobono, Rome, Italy, attested by geochemical and petrographic analysis. Geoarchaeology 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21702

Palladino DM, Simei S, Sottili G, Trigila R (2010) Integrated approach for the reconstruction of stratigraphy and geology of Quaternary volcanic terrains: an application to the Vulsini Volcanoes (central Italy). In: Groppelli G, Viereck L (eds) Stratigraphy and geology in volcanic areas. Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 464:66–84

Farr J, Marra F, Terrenato N (2015) Geochemical identification criteria for “peperino” stones employed in ancient Roman buildings: a Lapis Gabinus case study. J Archaeol Sci Rep 3:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.05.014

Fedele L, Scarpati C, Lanphere M, Melluso L, Morra V, Perrotta A, Ricci G (2008) The Breccia Museo formation, Campi Flegrei, southern Italy: geochronology, chemostratigraphy and relationship with the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption. Bull Volcanol 70:1189–1219

Ferber JJ (1776) Travels thorough Italy, in the years 1771 and 1772. Described a serier of letters to Baron Born, on the Natural History particularly the mountains and volcanos of the country. London, Print. L. Davis. 432 p

Fisher RV, Schmincke HU (1984) Pyroclastic Rocks. Springer-Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg, XIV+472p

Flint RF, Sanders JE, Rodgers J (1960) Diamictite, a substitute term for symmictite. Geol Soc Am Bull 71(12):1809–1810

Fornaseri M, Scherillo A, Ventriglia U (1963) La regione vulcanica dei Colli Albani. CNR, Roma

Freda C, Gaeta M, Karner DB, Marra F, Renne PR, Taddeucci J, Scarlato P, Christensen JN, Dallai L (2006) Eruptive history and petrologic evolution of the Albano multiple maar (Alban Hills, Central Italy). Bull Volc 68:567–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-005-0033-6

GeoPortale (2009) Il territorio di Pianura tra Neapoli e Puteoli. Cavitá di Pianura storia. Sistema informativo territoriale della Campania. http://sit.regione.campania.it/cavitapianura/storia.html. Accessed 21 Sept 2020

Giaccio B, Sposato A, Gaeta M, Marra F, Palladino DM, Taddeucci J, Barbieri M, Messina P, Rolfo MF (2007) Mid-distal occurrences of the Albano Maar pyroclastic deposits and their relevance for reassessing the eruptive scenarios of the most recent activity at the Colli Albani Volcanic District, Central Italy. Quat Int 171–172:160–178

Giaccio B, Marra F, Hajdas I, Karner DB, Renne PR, Sposato A (2009) 40Ar/39Ar and 14C geochronology of the Albano maar deposits: implications for defining the age and eruptive style of the most recent explosive activity at the Alban Hills Volcanic District, Italy. J Volcanol Geoth Res 185(3):203–213

Giordano G, de Rita D, Cas RAF, Rodani S (2002) Valley Pond and Ignimbrite veneer deposits in small-volume phreatomagmatic ‘“Peperino Albano”’ basic ignimbrite, Lago Albano maar, Colli Abani volcano, Italy: Influence of topography. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 118:131–144

Giordano G, De Benedetti AA, Diana A, Diano G, Gaudioso F, Marasco F, Miceli M, Mollo S, Cas RAF, Funiciello R (2006) The Colli Albani mafic caldera (Roma, Italy): stratigraphy, structure and petrology. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 115:49–80

Gmelin L (1814) Some scount of the mountains of ancient Latium, in which the Mineral called Haüyne is found. In: Thomson T (ed) annals of philosophy, or, magazine of chemistry, mineralogy, mechanics, natural history, agriculture and arts. Article VII, Vol IV. p115–122

Guérin MF-E (1839) Dictionnaire pittoresque d’histoire naturelle et des phénomènes de la nature. Tome VIIème, Paris, p 653

Holloway RR (1994) The archaeology of early Rome and Latium. Routledge, London

Jackson M, Marra F (2006) Roman stone masonry: Volcanic foundations of the ancient city. Am J Archaeol 110:403–436

Jackson MD, Marra F, Hay RL, Cawood C, Winkler E (2005) The judicious selection and preservation of tuff and travertine building stone in ancient Rome. Archaeometry 47:485–510

Karner DB, Marra F, Renne P (2001a) The history of the Monti Sabatini and Alban Hills volcanoes: groundwork for assessing volcanic-tectonic hazards for Rome. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 107:185–219

Karner DB, Lombardi L, Marra F, Fortini P, Renne PR (2001b) Age of ancient monuments by means of building stone provenance: A case study of the tullianum, Rome, Italy. J Archaeol Sci 28:387–393

Kilburn C, McGuire B (2001) Italian Volcanoes. Dunedin Academic Pr Ltd; First Edition, 172p

Lanciani R (1897) The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Roma. MacMillan, London

Le Maitre RW (ed) (2002) Igneous rocks. A classification and glossary of terms. Recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks. Cambridge Univ. Press. Cambridge. 254p

Locardi E (1965) Tipi di ignimbrite di magmi mediterranei: le ignimbriti del vulcano di Vico. Atti Soc Tosc Sc Nat 72:55–173

Lugli G (1957) La tecnica edilizia romana con particolare riguardo a Roma e Lazio, Bardi, Roma

MacDonald GA (1972) Volcanoes. A discussion of volcanoes, volcanic products, and volcanic phenomena. Prentice-Hall, International, New Jersey, XII+510p

Marra F, Rosa C (1995) Stratigrafia e assetto geologico dell’area romana, in “La Geologia di Roma. Il Centro Storico.” Mem Descr Carta Geol D’it 50:49–118

Marra F, D’Ambrosio E, Gaeta M, Mattei M (2018) Geochemical fingerprint of Tufo Lionato blocks from the Area Sacra di Largo Argentina: implications for the chronology of volcanic building stones in ancient Rome. Archaeometry 60:641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12343

Marra F, Freda C, Scarlato P, Taddeucci J, Karner DB, Renne PR, Gaeta M, Palladino DM, Trigila R, Cavarretta G (2003) Post-caldera activity in the Alban Hills volcanic district (Italy): 40Ar/39Ar geochronology and insights into magma evolution. Bull Volcanol 65:227–247

Marra F, Karner DB, Freda C, Gaeta M, Renne PR (2009) Large mafic eruptions at the Alban Hills Volcanic District (Central Italy): chronostratigraphy, petrography and eruptive behavior. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 179:217–232

Marra F, Cardello GL, Gaeta M, Jicha BR, Montone P, Niespolo EM, Nomade S, Palladino DM, Pereira A, De Luca G, Florindo F, Frepoli A, Renne PR, Sottili G (2021) The Volsci Volcanic Field (central Italy): eruptive history, magma system and implications on continental subduction processes. Int J Earth Sci 110:689–718

Mattias PP, Ventriglia U (1970) La regione vulcanica dei monti Sabatini e Cimini. Mem Soc Geol It 95:831–849

Menzies J (2009) Diamicton, In Encyclopedia of paleoclimatology and ancient environments (ed) Gornitz V. Springer, Dordrecht, p 278–279

Moderni P (1904) Contribuzione allo studio dei Vulcani Vulsini. Boll r Com Geol It 35:198–234

Moderni P (1903) Contribuzione allo studio dei Vulcani Vulsini. Boll R Com Geol It 34:121–147, 179–224, 333–375

Nappi G, Marini A (1986) I cicli eruttivi dei Vulsini orientali nell’ambito della vulcanotettonica del Complesso. Mem Soc Geol It 35:679–687

Nappi G, Renzulli A, Santi P (1991) Evidence of incremental growth in the Vulsinian calderas (central Italy). J Volcanol Geotherm Res 47:13–31

Palladino DM, Simei S (2005) Eruptive dynamics and caldera-collapse during the Onano eruption, Vulsini. Italy Bull Volcanol 67:423–440

Palladino DM, Gaeta M, Marra F (2001) A large K-foiditic hydromagmatic eruption from the early activity of the Alban Hills Volcanic District. Italy Bull Volcanol 63:345–359

Palladino DM, Gaeta M, Giaccio B, Sottili G (2014) On the anatomy of magma chamber and caldera collapse: the example of trachy-phonolitic explosive eruptions of the Roman Province (central Italy). J Volcanol Geotherm Res 281:12–26

Perrotta A, Scarpati C, Luongo G, Morra V (2006) The Campi Flegrei caldera boundary in the city of Naples. In: De Vivo B (ed) Volcanism in the Campania Plain: Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ignimbrites. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 85–96

de Rita D, Funiciello R, Corda L, Sposato A, Rossi U (1993) Volcanic units. In: Di Filippo M (ed) Sabatini Volcanic Complex. Quad Ric Sci 114. Progetto Finalizzato Geodinamica C.N.R., Roma, pp. 33–79

Rittmann A (1950) Rilevamento geologico della Collina dei Camaldoli nei Campi Flegrei. Bull Soc Geol It 69:129–177

Rittmann A (1967) I vulcani e la loro attività. Cappelli, Bologna, p 359p

Roth J (1887) Algemenie und Chemische Geologie. Berlin, Verlag von W. Hertz. II Band.703p

Sabatini V (1896) Relazione del lavoro eseguito nell’anno 1895 sui vulcani dell’Italia centrale e loro prodotti. Bollettino del R. Comitato geologico d’Italia, 1896, vol. 27, pp. 400–405

Scarpati C, Sparice D, Perrotta A (2020) Dynamics of large pyroclastic currents inferred by the internal architecture of the Campanian Ignimbrite. Sci Rep 10:22230

Scrope GP (1825) Considerations on Volcanos, the probable cause of their phenomena, the laws which determine their march, the disposition of their products, and their connection with the present state and past history of the globe; leading to the establishment of a new theory of the Earth. Printed W.Phillips, G. Yard, Lombard Street, Edinburgh. 270p

Scrope GP (1827) Memoir on the geology of Central France; Including the volcanic formations of Auvergne, the Velay and the Vivarais. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, London, 79p

Scrope G.P. (1858). The geology of extinct volcanos of Central France. London. J. Murray Ed. 2d ed. 323p.

Sigurdsson H, Houghton B, McNutt S, Rymer H, Stix J (eds) (2015) The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, 2nd edn. Academic Press, Elsevier, p 1456p

Skilling I, White JDL, McPhie J (2002) Peperite: a review of magma–sediment mingling. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 114(1–2):1–17

Sottili G, Taddeucci J, Palladino DM, Gaeta M, Scarlato P, Ventura G (2009) Sub-surface dynamics and eruptive styles of maars in the Colli Albani Volcanic District, Central Italy. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 180:189–202

Sottili G, Palladino DM, Marra F, Jicha B, Karner DB, Renne P (2010) Geochronology of the most recent activity in the Sabatini Volcanic District, Roman Province, central Italy. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 196:20–30

Sottili G, Palladino DM, Gaeta M, Masotta M (2012) Origins and energetics of maar volcanoes: examples from the ultrapotassic Sabatini Volcanic District (Roman Province, Central Italy). Bull Volcanol 74:163–186

Torelli M (1968) Il donario di M. Fulvio Flacco nell’area di S. Omobono. Quaderni dell’Istituto di Topografia Antica della Università di Roma, 5: 71–76

Ventriglia U (1971) La Geologia della Città di Roma. Amministrazione Provinciale di Roma

Vernia L, Bargossi GM, Di Battistini G, Montanini A (1995) Caratteri geopetrografici e vulcanologici del settore sud-orientale vulsino (Montefiascone-Commenda, Viterbo). Boll Soc Geol Ital 114:665–677

Vezzoli L, Conticelli S, Innocenti F, Landi P, Manetti P, Palladino DM, Trigila R (1987) Stratigraphy of the Latera Volcanic Complex: proposals for a new nomenclature. Per Mineral 56:89–110

White J, McPhie J, Skilling I (2000) Peperite: a useful genetic term. Bull Volcanol 62:65–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004450050293

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge an anonymous reviewer, the Review Editor Ulrich Kueppers and the Executive Editor Andrew Harris for very helpful comments that greatly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editorial responsibility: U. Kueppers

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marra, F., Palladino, D.M. & Licht, O.A.B. The peperino rocks: historical and volcanological overview. Bull Volcanol 84, 69 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-022-01573-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-022-01573-5