Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) plus anlotinib as third-line treatment in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC).

Methods

A total of 120 patients with ES-SCLC who were admitted to Shandong Cancer Hospital between January 2019 and December 2020 were retrospectively analyzed. They were divided into the observation group (n = 62) and the control group (n = 58) according to their different treatment plans. The observation group was given ICI plus anlotinib, while the control group was given anlotinib alone. The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival (PFS), and the secondary endpoints were the objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR). An efficacy evaluation was carried out every 6 weeks. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify the prognostic factors. The main treatment-related adverse events were evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0.

Results

In the observation group and the control group, the DCRs were 87.1% and 72.4% (p = 0.044), and the ORRs were 19.4% and 6.9% (p = 0.045), respectively. The median PFS was longer in the observation group (7.5 months) than in the control group (4.6 months) (p = 0.0033). In Cox regression analysis, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score, brain metastases and metastatic sites were prognostic factors of ICI plus anlotinib. Compared with the control group, grade 1–2 immune-related pneumonia and hypothyroidism of patients in the observation group were significantly increased (p < 0.05), but grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse reactions were not significantly increased (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

ICI plus anlotinib showed promising efficacy and manageable toxicity in third-line treatment of ES-SCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for 13–17% of all lung cancers, and smoking is the primary risk factor for SCLC (Oronsky et al. 2017; Govindan et al. 2006). SCLC has the characteristics of a high degree of malignancy and early metastasis. Therefore, the majority of patients are already in an extensive stage at the time of diagnosis (Kalemkerian 2016; Simon and Wagner 2003). Therapeutic options for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) are limited. Chemotherapy plays an important role in the initial treatment of ES-SCLC. However, most patients develop recurrent disease after initial treatment, often with additional sites of metastasis (Ito et al. 2017). The emergence of targeted therapy and immunotherapy is promising for the treatment of SCLC.

Anlotinib is a small molecule oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor that has the function of inhibiting angiogenesis and antitumor proliferation (Lin et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2016). It has been approved by the China National Medical Products Administration for ≥ third-line treatment of advanced SCLC (Cheng et al. 2018). Programmed death receptor 1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors are commonly used immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors can not only restore the activity of T cells but also enhance the immune effect of T cells, thereby killing tumors (Efremova et al. 2018). A large number of studies have confirmed that PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors can benefit ES-SCLC patients in terms of survival (Ready et al. 2019; Chung et al. 2020; Horn et al. 2018; Paz-Ares et al. 2019).

An increasing number of studies have shown that anlotinib and ICIs complement each other and play a synergistic role in antitumor therapy. First, anlotinib can normalize tumor blood vessels and improve the immune microenvironment of the tumor. In addition, the decrease in PD-L1 expressed by endothelial cells can cause an increase in VEGFR-2, indicating that PD-L1 has a potential regulatory effect on tumor angiogenesis (Jiang et al. 2015; Allen et al. 2017; Ramjiawan et al. 2017). Studies have confirmed that ICI plus anlotinib has a significant effect on the treatment of advanced NSCLC (Zhang et al., 2021; Liang and Wang 2019). Additionally, there was a study showing that anlotinib plus a PD-1 inhibitor may also be effective in the second-line or later treatment of relapsed SCLC (Zhang et al. 2021). Herein, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of ICI plus anlotinib versus anlotinib alone to find a high-efficiency and manageable-toxicity third-line treatment for ES-SCLC.

Materials and methods

Patients

We reviewed the electronic medical records of 120 patients with ES-SCLC who received anlotinib alone (n = 58) or ICI plus anlotinib (n = 62) for third-line treatment from January 2019 to December 2020 at Shandong Cancer Hospital, China. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age at diagnosis between 18 and 75 years, (ii) the presence of pathologically or cytologically confirmed SCLC, (iii) the presence of imaging confirmed extensive stage, (iv) a prior lack of response or intolerance to two lines of treatment, (v) the presence of at least one measurable lesion as defined by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, (vi) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0–2, (vii) and no prior anlotinib or ICIs. Patients with NSCLC, uncontrolled hypertension, a bleeding tendency, ischemic cardiovascular disease, or severe liver and kidney dysfunction were excluded from the study.

A total of 58 patients received anlotinib alone. Anlotinib (Chia Tai Tianqing Pharmaceutical, China) was administered orally once daily (8 mg, 10 mg or 12 mg) on Days 1–14 of a 21-day cycle. A total of 62 patients received ICI plus anlotinib. Anlotinib (Chia Tai Tianqing Pharmaceutical, China) was administered orally once daily (8 mg, 10 mg or 12 mg) on Days 1–14 of a 21-day cycle. At the same time, the patients were treated with an ICI. The ICIs included sintilimab, toripalimab, camrelizumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab or durvalumab (Table 1). Tolerance and efficacy were evaluated every 6 weeks. The treatment was continued until disease progression, clinical deterioration, or unacceptable toxicity.

This study was approved by the ethics review board of the Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences. The requirement for informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature of the study.

Evaluation of efficacy and adverse events

According to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 (Eisenhauer et al. 2009), an objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the sum of a complete response (CR) and a partial response (PR); disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the sum of CR, PR and stable disease (SD); PFS was calculated as the time from the initiation of treatment to progressive disease (PD) or death. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were divided into grades I–IV according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 (Freites-Martinez et al. 2021); the higher the grade, the worse the AEs.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) or GraphPad Prism 8.0 (La Jolla, California, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. The median PFS was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the survival curves were compared with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to analyze the correlation of baseline clinical characteristics with the efficacy of ICI plus anlotinib. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 120 patients were included in this study. In the observation group, 38 (61.3%) were men and 24 (38.7%) were women. In the control group, 43 (74.1%) were men and 15 (25.9%) were women. All of them were aged 18–75. There were no significant differences in sex, age, smoking history, drinking history, ECOG PS, brain metastases, liver metastases, or metastatic sites between the two groups (p > 0.05). The baseline characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 2.

Efficacy

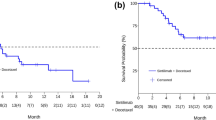

All patients received at least 6 weeks of treatment and follow-up. The ORR of the observation group was higher than that of the control group (19.4% vs. 6.9%, p = 0.045). The DCRs of the observation group and the control group were 87.1% and 72.4%, respectively (p = 0.044) (Table 3). As exhibited in Fig. 1, the median PFS of the observation group was 7.5 months (95% CI 5.5–9.6 months) and that of the control group was 4.6 months (95% CI 3.0–6.2 months, p = 0.0033). In the observation group, the median PFS of patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors was not significantly different from that of patients treated with PD-L1 inhibitors (8.1 vs. 7.5 months, p = 0.5992) (Fig. 2). Through univariate and multivariate analysis, we found that sex, age, smoking history, drinking history and liver metastases had no influence on the median PFS of ICI plus anlotinib, but ECOG PS, brain metastases and metastatic sites were reliable factors of prognosis (Table 4). As presented in Figs. 3, 4 and 5, among all patients in the observation group, the median PFS of patients without brain metastases was 7.5 months, and the median PFS of patients with brain metastases was 4.6 months (p = 0.0062). Patients who had an ECOG PS of 0–1 had a significantly higher median PFS than patients with an ECOG PS of 2 (8.2 vs. 4.6 months, p = 0.0056). Patients with less than or equal to three metastatic sites had a higher PFS than those with more than three metastatic sites (10.6 vs. 4.0 months, p = 0.0054).

Safety

Eleven patients in the observation group and 0 in the control group experienced grade 1–2 hypothyroidism (p = 0.002). In addition, between-group significant differences were also seen for grade 1–2 immune-related pneumonia (11.3% in the observation group vs. 0% in the control group, p = 0.008). There were no significant differences between the two groups for grade 3–4 AEs. The key grade 3–4 AEs in the observation group were hypertension (p = 0.808), bone marrow suppression (p = 0.168), vomiting/diarrhea (p = 0.168), gingival bleeding (p = 0.331), gastrointestinal bleeding (p = 0.331), hypothyroidism (p = 0.168), hand–foot syndrome (p = 0.526) and immune-related pneumonia (p = 0.090). Six patients reduced the dose of anlotinib due to TRAEs in the control group. Treatment discontinuation occurred in two patients, and drug reduction occurred in ten patients due to TRAEs in the observation group. No patients in either group experienced treatment-related death (Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

The findings of the retrospective study proved that anlotinib combined with ICI is a promising regimen for the third-line treatment of patients with ES-SCLC. Although Group 1–2 hypothyroidism and immune-related pneumonia were significantly higher under anlotinib plus ICI, no treatment-related deaths occurred. ICI plus anlotinib is safe and tolerable.

In our study, the results for the control group were slightly higher than the findings of the ALTER1202 trial (Cheng et al. 2018), which assessed the efficacy and safety of anlotinib as a third-line or further-line in relapsed SCLC. The results of the ALTER1202 trial showed that the ORR (4.94% vs. 2.63%, p = 1.0000), DCR (71.60% vs. 13.16%, p < 0.0001) and median PFS (4.1 vs. 0.7 months, p < 0.0001) were higher in the anlotinib group than in the placebo group. In our study, the ORR (6.9%), DCR (72.4%) and PFS (4.6 months) of the anlotinib group were higher than those in the ALTER1202 study. The reason for this may be that anlotinib was only used as the third-line treatment in our study while it was used not only as third-line treatment but also as further-line treatment in the ALTER1202 trial.

Although a large number of studies have proven that ICIs are effective in the treatment of SCLC, the appropriate time for the use of ICIs is uncertain. Studies have shown that PD-L1 inhibitors and PD-1 inhibitors are effective in the first-line treatment of ES-SCLC (Horn et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Paz-Ares et al. 2018; Leal et al. 2020). However, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors failed to demonstrate significant efficacy in maintenance therapy and second-line treatment after first-line treatment of ES-SCLC (Pujol et al. 2019; Owonikoko et al. 2019; Spigel et al. 2021; Goldman et al. 2018; Gadgeel et al. 2018). PD-1 inhibitors have been proven useful in third-line and more treatment of ES-SCLC. The results of the CheckMate-032 study subgroup analysis showed that nivolumab as a single agent of the third line and above treatment for SCLC had an ORR of 11.9% and a median duration of response (DOR) of 17.9 months. The median PFS was 1.4 months (95% CI 1.3–1.6 months), and the incidence of grade 3–4 AEs was 11.9% (Ready et al. 2019). This suggests that nivolumab is long lasting and well tolerated as a third line and above treatment for SCLC. The KEYNOTE028/158 study analyzed the efficacy of another PD-1 inhibitor, pembrolizumab, in the third line and above treatment of SCLC. The results showed that the ORR of pembrolizumab was 19.3% (95% CI 11.4–29.4%), the PFS was 2.0 months (95% CI 1.9–3.4 months), and the median OS was 7.7 months (95% CI 5.2–10.1 months) (Chung et al. 2020). However, the efficacy of PD-L1 inhibitors after two or more lines of previous therapy in patients with ES-SCLC remains unknown. In view of the large difference in efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors and PD-L1 inhibitors in the treatment of SCLC and the uncertainty of the timing of their use, we analyzed PD-1 inhibitors and PD-L1 inhibitors in separate groups. In our study, the median PFS in the PD-1 inhibitor group was 8.1 months and that in the PD-L1 inhibitor group was 7.5 months (p = 0.5992). Hence, regardless of whether anlotinib was combined with a PD-1 inhibitor or PD-L1 inhibitor, there was no significant difference in median PFS.

Brain metastasis is considered to be one of the factors affecting the prognosis. In the observation group, the median PFS of patients without brain metastases was significantly longer than that of patients with brain metastases (p = 0.0062). The incidence of brain metastases from lung cancer is the highest of all tumors, and more than 25% of patients develop brain metastases during the course of the disease (Zimm et al. 1981; Sheehan et al. 2002). In established brain metastases, the tumor microenvironment is comprised of the innate immune system, namely, microglia and macrophages, and adaptation to the immune system is mainly achieved through T cells. On the one hand, brain metastases can manipulate the metabolites and matrix components in their microenvironment to influence the immune response. On the other hand, brain metastases can regulate and activate the function of microglia and produce inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-α, which can lyse target cells (Holmgaard et al. 2015; Munn and Mellor 2016; He et al. 2006). There are prerequisites for a response to immunotherapy in the microenvironment of brain metastases. In addition, the efficacy of anlotinib in patients with brain metastases was proven by the ALTER 1202 trial subgroup analysis, which showed that the PFS of patients with brain metastases was prolonged by 3 months (3.8 vs. 0.8 months, HR 0.15), and OS was prolonged by 3.7 months (6.3 vs. 2.6 months, HR 0.23) (Cheng et al. 2019). Therefore, for ES-SCLC patients with brain metastases, we recommend the use of anlotinib combined with ICIs as third-line treatment.

ECOG PS is also one of the independent factors affecting the therapeutic effect of anlotinib plus ICI. The results showed that the median PFS in patients with ECOG PS of 0–1 was much longer than that in patients with ECOG PS of 2 (p = 0.0056), which is consistent with a meta-analysis of SCLC at different stages. The meta-analysis showed that patients with a PS score of 0–1 have the best prognosis, and patients with a PS score of ≥ 2 have the worst prognosis (Foster et al. 2009). The higher the ECOG PS, the shorter the survival period (Reck et al. 2012). Therefore, when the physical condition is good and the ECOG PS score is low, ICI plus anlotinib shows promising efficacy as the third-line treatment of ES-SCLC.

In addition, the number of metastatic sites is also one of the nonnegligible factors that affect the efficacy of ICIs plus anlotinib. In our study, the median PFS of patients with less than three metastases was higher than that of patients with more than three metastases (10.6 vs. 4.0 months, p = 0.0054). This result suggests that the lower the number of metastatic sites, the better the efficacy of ICI plus anlotinib.

However, our study also has shortcomings. Due to the nature of retrospective research, selection bias is inevitable and may result in lower reliability of the judgment of comprehensive safety or efficacy of both regimens. In addition, due to the different physical conditions of the patients and the small sample size, we could not analyze the different doses of anlotinib between the groups. Furthermore, other outcomes, such as OS and health-related quality of life, were not analyzed in this study.

In general, anlotinib plus ICI can achieve promising survival outcomes among patients with ES-SCLC, and the TRAEs are safe and tolerable. Brain metastases, metastasis sites and ECOG PS are factors affecting the prognosis. The therapeutic effect was equivalent whether anlotinib was combined with a PD-1 inhibitor or a PD-L1 inhibitor.

Data availability

Datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available from QC on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Allen E, Jabouille A, Rivera LB et al (2017) Combined antiangiogenic and anti-PD-L1 therapy stimulates tumor immunity through HEV formation. Sci Transl Med 9(385):1–13

Cheng Y, Wang Q, Li K et al (2018) Anlotinib as third-line or further-line treatment in relapsed SCLC: a multicentre, randomized, doubleblind phase 2 trial. J Thorac Oncol 13(10):S351–S352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.308

Cheng Y, Wang Q, Li K et al (2019) The impact of anlotinib for relapsed SCLC patients with brain metastases: a subgroup analysis of ALTER 1202. J Thorac Oncol 14(10):S823–S824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.1771

Chung HC, Piha-Paul SA, Lopez-Martin J et al (2020) Pembrolizumab after two or more lines of previous therapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic SCLC: results from the KEYNOTE-028 and KEYNOTE-158 studies. J Thorac Oncol 15(4):618–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.109

Efremova M, Rieder D, Klepsch V et al (2018) Targeting immune checkpoints potentiates immunoediting and changes the dynamics of tumor evolution. Nat Commun 9(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02424-0

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45(2):228–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

Foster NR, Mandrekar SJ, Schild SE et al (2009) Prognostic factors differ by tumor stage for small cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of North Central Cancer Treatment Group trials. Cancer 115(12):2721–2731. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24314

Freites-Martinez A, Santana N, Arias-Santiago S et al (2021) Using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE-Version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of adverse events of anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (engl Ed) 112(1):90–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2019.05.009

Gadgeel SM, Pennell NA, Fidler MJ et al (2018) Phase II study of maintenance pembrolizumab in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC). J Thorac Oncol 13(9):1393–1399

Goldman JW, Dowlati A, Antonia SJ et al (2018) Safety and antitumor activity of durvalumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated extensive disease small-cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC). J Clin Oncol 36(15):8518. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.8518

Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D et al (2006) Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 24(28):4539–4544. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859

He BP, Wang JJ, Zhang X et al (2006) Differential reactions of microglia to brain metastasis of lung cancer. Mol Med 12(7–8):161–170. https://doi.org/10.2119/2006-00033.He

Holmgaard RB, Zamarin D, Li Y et al (2015) Tumor-expressed IDO recruits and activates MDSCs in a Treg-dependent manner. Cell Rep 13(2):412–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.077

Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczesna A et al (2018) First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 379(23):2220–2229. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1809064

Ito T, Kudoh S, Ichimura T et al (2017) Small cell lung cancer, an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like cancer: significance of inactive Notch signaling and expression of achaete-scute complex homologue 1. Hum Cell 30(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-016-0149-3

Jiang W, Huang Y, An Y et al (2015) Remodeling tumor vasculature to enhance delivery of intermediate-sized nanoparticles. ACS Nano 9(9):8689–8696. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b02028

Kalemkerian GP (2016) Small cell lung cancer. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 37(5):783–796. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1592116

Leal T, Wang YT, Dowlati A et al (2020) Randomized phase II clinical trial of cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide (CE) alone or in combination with nivolumab as frontline therapy for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC): ECOG-ACRIN EA5161. J Clin Oncol 38(15):9000

Liang H, Wang M (2019) Prospect of immunotherapy combined with anti-angiogenic agents in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res 11:7707–7719. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.628124

Lin B, Song X, Yang D et al (2018) Anlotinib inhibits angiogenesis via suppressing the activation of VEGFR2, PDGFRbeta and FGFR1. Gene 654:77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2018.02.026

Liu SV, Reck M, Reinmuth N et al (2019) Updated overall survival and PD-L1 subgroup analysis of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer treated with atezolizumab, carboplatin, and etoposide (IMpower133). J Clin Oncol 37(7):537–546. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20

Munn DH, Mellor AL (2016) IDO in the tumor microenvironment: inflammation, counter-regulation, and tolerance. Trends Immunol 37(3):193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2016.01.002

Oronsky B, Reid TR, Oronsky A et al (2017) What’s new in SCLC? A review. Neoplasia 19(10):842–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2017.07.007

Owonikoko TK, Kim HR, Govindan R et al (2019) Nivolumab (nivo) plus ipilimumab (ipi), nivo, or placebo (pbo) as maintenance therapy in patients (pts) with extensive disease small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC) after first-line (1L) platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo): results from the double-blind, randomized phase III CheckMate 451 study. Ann Oncol 30:77–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz094

Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D et al (2018) Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 379(21):2040–2051. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1810865

Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y et al (2019) Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 394(10212):1929–1939. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32222-6

Pujol J-L, Greillier L, Audigier-Valette C et al (2019) A randomized non-comparative phase II study of anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1 atezolizumab or chemotherapy as second-line therapy in patients with small cell lung cancer: results from the IFCT-1603 trial. J Thorac Oncol 14(5):903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.008

Ramjiawan RR, Griffioen AW, Duda DG (2017) Anti-angiogenesis for cancer revisited: is there a role for combinations with immunotherapy? Angiogenesis 20(2):185–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-017-9552-y

Ready N, Farago AF, de Braud F et al (2019) Third-line nivolumab monotherapy in recurrent SCLC: CheckMate 032. J Thorac Oncol 14(2):237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.10.003

Reck M, Thatcher N, Smit EF et al (2012) Baseline quality of life and performance status as prognostic factors in patients with extensive-stage disease small cell lung cancer treated with pemetrexed plus carboplatin vs. etoposide plus carboplatin. Lung Cancer 78(3):276–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.09.002

Sheehan J, Sun M, Kondziolka D et al (2002) Radiosurgery for non-small cell lung carcinoma metastatic to the brain: long-term outcomes and prognostic factors influencing patient survival time and local tumor control. J Neurosurg 97(6):1276–1281. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2002.97.6.1276

Simon GR, Wagner H (2003) Small cell lung cancer. Chest 123(1 Suppl):259S-271S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.259s

Spigel DR, Vicente D, Ciuleanu TE et al (2021) Second-line nivolumab in relapsed small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate 331. Ann Oncol 32(5):631–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.071

Sun Y, Niu W, Du F et al (2016) Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor properties of anlotinib, an oral multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Hematol Oncol 9(1):105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-016-0332-8

Zhang X, Zeng L, Li Y et al (2021) Anlotinib combined with PD-1 blockade for the treatment of lung cancer: a real-world retrospective study in China. Cancer Immunol Immunother 70(9):2517–2528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-021-02869-9

Zhou N, Jiang M, Li T et al (2021) Anlotinib combined with anti-PD-1 antibody, camrelizumab for advanced NSCLCs after multiple lines treatment: an open-label, dose escalation and expansion study. Lung Cancer 160:111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.08.006

Zimm S, Wampler GL, Stablein D et al (1981) In tracerebrai metastases in solid-tumor patients: natural history and results of treatment. Cancer 48(2):384–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19810715)48:2%3c384::aid-cncr2820480227%3e3.0.co;2-8

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Shandong Key Research and Development Program (Grant number: 2019GSF108251) for the support of a grant.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Shandong Key Research and Development Program (Grant number: 2019GSF108251).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by QC, YL, SJY, WJZ, and CW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by QC, and all authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Ethics approval

This retrospective study was performed using data from anonymized patients who received ICIs plus anlotinib treatment between January 2019 and December 2020. Because of the nature of retrospective design and patient anonymization, the ethical board of the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences approved the retrospective study.

Consent to participate

The need for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to publication of the results presented in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Li, Y., Zhang, W. et al. Safety and efficacy of ICI plus anlotinib vs. anlotinib alone as third-line treatment in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 148, 401–408 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03858-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03858-2