Abstract

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is associated with brain pathology extending beyond temporal lobe structures. We sought to look for informative patterns of brain tissue properties in TLE that go beyond the established morphometry differences. We hypothesised that volume differences, particularly in hippocampus, will be paralleled by changes in brain microstructure. The cross-sectional study included TLE patients (n = 25) from a primary care center and sex-/age-matched healthy controls (n = 55). We acquired quantitative relaxometry-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data yielding whole-brain maps of grey matter volume, magnetization transfer (MT) saturation, and effective transverse relaxation rate R2* indicative for brain tissue myelin and iron content. For statistical analysis, we used the computational anatomy framework of voxel-based morphometry and voxel-based quantification. There was a positive correlation between seizure activity and MT saturation measures in the ipsilateral hippocampus, paralleled by volume differences bilaterally. Disease duration correlated positively with iron content in the mesial temporal lobe, while seizure freedom was associated with a decrease of iron in the very same region. Our findings demonstrate the link between TLE clinical phenotype and brain anatomy beyond morphometry differences to show the impact of disease burden on specific tissue properties. We provide direct evidence for the differential effect of clinical phenotype characteristics on processes involving tissue myelin and iron in mesial temporal lobe structures. This study offers a proof-of-concept for the investigation of novel imaging biomarkers in focal epilepsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is mounting evidence for brain pathology extending beyond the temporal lobe in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)—one of the most common forms of focal epilepsy. Theoretical work and animal models suggest that TLE-related brain remodeling follows a specific temporal trajectory, with both focal and distributed cortico-subcortical changes that are further modulated in the course of disease (Bernhardt et al. 2013a; Sutula 2004). Most recent reports support the notion of dynamic bidirectional brain anatomy changes related to disease progression, where the initial seizure-induced boost in neurogenesis is followed by gliosis due to depletion of hippocampal stem cells and shift towards astrocytes production (Sierra et al. 2015a, b). Cross-sectional (Bonilha et al. 2004) and longitudinal computational anatomy studies (Bernhardt et al. 2013b) in TLE patients provide indirect evidence for this process, showing hippocampal volume loss in the chronic stages of disease. Given the gap of knowledge about the neurobiology underlying TLE-associated gray matter volume and cortical thickness changes, new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques provide a window of opportunity to assess pathology related to brain’s iron and myelin homeostasis.

Animal models confirmed the notion that seizures induce axonal and myelin loss in the hippocampus paralleled by dysfunctional axonal sprouting and re-myelination (Savaskan and Nitsch 2001). Under the supposition of seizure-induced neurogenesis rate increase, evidence from animal models shows that newly generated neuronal granule cells migrate into the hilus as far as the hippocampal CA3, where due to abnormal integration into hippocampal networks they start contributing to recurrent excitatory circuits (Scharfman et al. 2000). This seizure-related aberrant network development is followed by hippocampal myelin loss and fiber degeneration in TLE, especially for small diameter axons, demonstrated by animal models and post mortem investigations (Ozdogmus et al. 2009). Correspondingly, human studies demonstrate increased oligodendroglia density and subsequent gliosis in white matter areas adjacent to the seizure onset zone (Kasper and Paulus 2004; Stefanits et al. 2012). Supported by findings showing epilepsy-associated changes of hilar ectopic granule cells (Scharfman et al. 2000) paralleled by changes in myelinated fibers (Luo et al. 2015; Ye et al. 2013), myelin-sensitive neuroimaging techniques would allow to probe microstructural tissue differences in TLE patients.

In the context of TLE, there is strong evidence from animal models about the epileptogenic role of abnormal iron homeostasis in combination with blood–brain-barrier leakage, local inflammation and cellular oxidative stress in the hippocampus (Duffy et al. 2012; van Vliet et al. 2007). Recent studies demonstrate an association between seizure activity, histological and neuroimaging signatures corresponding to pathological iron deposits (Aggarwal et al. 2018). Ferroptosis—the regulated cell death dependent on iron, occurs in the hippocampus following pharmacological-induced TLE in rodents (Ye et al. 2019). Confirmatory for this notion, there is compelling evidence that inhibitors targeting iron homeostasis can prevent hippocampal ferroptosis and ameliorate cognitive impairment associated to TLE (Ye et al. 2019). Human studies find a similar relationship between epilepsy and seizure-dependent inflammation in association to altered iron transfer and iron saturation rates (Tombini et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014).

The majority of computational anatomy studies in epilepsy rely on T1- and T2-weighted brain imaging data that are governed by unknown MR contrast contributions, which are a function of the underlying tissue properties. Morphometric features—cortical thickness, surface area or grey matter volume, extracted from this type of MRI data, are heavily dependent on local MR contrast properties that remain unaccounted for across all surface- and voxel-based methods at hand. The missing link between brain tissue properties and resulting morphometry results hinder the straightforward neurobiological interpretation of “spurious” findings (Lorio et al. 2016b). Recent advances in qMRI provide the opportunity to assess in vivo quantitatively specific tissue properties in the healthy and diseased brain with particular focus on myelin, iron and tissue free water content (Draganski et al. 2011; Weiskopf et al. 2013).

Up to date, detection of tissue microstructure pathology in TLE was restricted to histology studies of post-surgery ex-vivo tissue samples that showed altered intracortical myelination and fiber arrangement, particularly in superficial cortical layers (Thom et al. 2000). The combination of state-of-the-art histology and ex-vivo MRI-based morphometry confirmed the spatial correspondence between axonal degeneration of temporopolar white matter and blurring of grey-white matter boundaries (Garbelli et al. 2012). Recent qMRI study in TLE patients demonstrated an ipsilateral cortical and hippocampal increase of the longitudinal relaxation time—a measure sensitive to intracortical myelin, however, with unaccounted contribution of the effects of iron (Bernhardt et al. 2018). This was interpreted as a sign of disrupted fiber architecture that finds correlates in histology specimens of TLE patients.

Our in-vivo study investigated the differences in brain tissue properties associated with TLE clinical phenotype characteristics—disease duration and frequency, beyond the established brain morphometry assessment in TLE patients. To this aim, we acquired qMRI data according to our established relaxometry-based protocol followed by state-of-the-art whole-brain statistical analysis using voxel-based quantification (VBQ) in SPM12s computational anatomy framework (Draganski et al. 2011). We hypothesized that individuals’ seizure frequency and overall duration will correlate with tissue property patterns in hippocampus and associated nodes of limbic circuits.

Methods

Participants

For this cross-sectional study, we recruited patients with left-lateralized pharmaco-responsive and -resistant TLE (n = 25; 13 females, mean age ± standard deviation 40.9 ± 14.9 years, age range—18 to 69 years old) and sex-/age-matched healthy volunteers (n = 55; 28 females, mean age ± standard deviation 36.8 ± 14.6 years, age range 19–72 years old; see Table 1). Handedness was estimated based on the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory and classified into right-handedness dependent on scores superior to + 40, ambidexter—with scores between − 40 and + 40 and left handedness—scores inferior to − 40 (Oldfield 1971).

The decision to restrict the analysis to only left lateralized TLE aimed to differentiate unilateral versus bihemispheric effects. The protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee and prior to study inclusion we obtained written informed consent from each participant. All procedures were performed in accordance with national and international guidelines.

The diagnosis of mesial TLE followed the criteria of the International League Against Epilepsy (Berg et al. 2010) including (i) clinical aspects of seizures such as semiology, onset and history; (ii) standard and/or long-term video-electroencephalography (EEG) and (iii) neuro-radiological assessment. Clinical 3 Tesla MRI was obtained according to established protocols (Wellmer et al. 2013) at University Hospital CHUV Lausanne, and reviewed by a neuroradiologist with special expertise in epileptology (for pharmaco-responsiveness and -resistance, see “Results” section). The evaluation of the lateralization of the epileptogenic seizure onset zone depended on seizure semiology, evidence of unilateral epileptiform activity on EEG, and MRI findings. Patients without strong evidence for lateralization of the seizure onset zone or with a bilateral, lateral temporal or extra-temporal epileptogenic focus (focal cortical dysplasia or lateral temporal sclerosis) were excluded from subsequent analysis, as we aimed at investigating structural changes in temporal lobe epilepsy including a clear epileptogenic focus. Additional exclusion criteria included a history of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, autoimmune etiologies of epilepsy, history of traumatic brain injury, evidence of ischemic or hemorrhagic brain lesions, tumors, or neuro-radiological diagnosis of brain pathology beyond hippocampal and mesial temporal lobe sclerosis.

Following radiological evaluation criteria, our cohort consists of 5 patients with lesional epilepsy (3—with hippocampal sclerosis, 1—with hippocampal dysplasia, and 1—with hippocampal malrotation), while for the remaining 20 patients, clinical MRI did not show any evident lesion. The definition of epileptogenic focus lateralization was based on inter-ictal epileptiform discharges. 21 patients were drug responsive, i.e. seizure-free since more than 5 years, 4 patients were resistant to antiepileptic drug treatment, dependent on consensus definition of the International League Against Epilepsy (Kwan et al. 2010).

To quantify epilepsy severity, we documented and calculated the number of auto-reported generalized tonic–clonic seizures across life time and of focal seizures without generalization within the last 12 months. The date of MRI acquisition is used as endpoint for the time interval of interest. We refrained from including reports of focal seizures without generalization dating back more than 12 months ago given the expected lack of precision, particularly for non-generalized seizures. Only 3 out of the 25 patients presented focal seizures without generalization. 1 of the 3 patients did not have any focal seizure within 12 months before data acquisition.

Disease duration was calculated as the time span between the first seizure and MRI data acquisition. The seizure-free interval represented the time between the last seizure and MRI data acquisition. 6 patients were in remission with a free interval of more than 5 years for generalized seizures and 4 out of these 6 patients were in remission for focal seizures too.

Magnetic resonance imaging data acquisition

We acquired quantitative MRI (qMRI) data on a 3 Tesla MRI system (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Medical Systems, Germany) using a 64-channel radio-frequency receive head coil and body coil for transmission. The protocol consisted of three multi-echo 3D fast low angle shot (FLASH) with proton density (TR/α = 24.5 ms/6°), T1 (TR/α = 24.5 ms/21°), and magnetization transfer (MT) (TR/α = 24.5 ms/6°)-weighted contrasts (Helms et al. 2008) using a field-of-view of 240 × 256 × 176 mm along with the A-P, H-F and L-R directions and isotropic voxel sizes of 1 × 1 × 1 mm (Weiskopf et al. 2013). We used parallel imaging along the phase encoding (acceleration factor 2, GRAPPA image reconstruction) and Partial Fourier 6/8 in the partition direction to speed up data acquisition. Data was acquired for mapping inhomogeneities of the radio-frequency transmit field B1 using a 3D Echo Planar Imaging spin-echo/stimulated-echo method (Lutti et al. 2012). The acquisition parameters were as follows: TR = 500 ms, TE = 39.06 ms, TM = 31.2 ms, FOV = 192 × 256 × 192 mm along with the A-P, H-F and L-R directions, image resolution = 4mm3. 2D dual-echo field map data was acquired to correct for image distortions in the EPI data using the SPM field map toolbox (Hutton et al. 2012). The total acquisition time was 27 min.

qMRI map calculation and image processing

For data preprocessing and analysis we use the established computational anatomy framework of SPM12s (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12) with voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and VBQ (Draganski et al. 2011) running under Matlab 7.13 (Mathworks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA). Regression of the log-signal from the 8 proton density-weighted echoes was used to calculate the R2* maps. Signals of six equidistant bipolar gradient echoes were averaged to augment the signal-to-noise ratio (Helms and Dechent 2009) before calculating the MT saturation maps (Weiskopf et al. 2013). All qMRI data were corrected for radiofrequency transmit inhomogeneities using the B1 maps (Lutti et al. 2014).

Image processing

For automated brain tissue classification and subsequent regional volume calculation, we used the MT saturation maps with SPM12s default settings of the “unified segmentation” framework (Ashburner and Friston 2005) and enhanced tissue probability maps providing higher sensitivity for detection of subcortical structures (Lorio et al. 2016a). We estimated spatial registration parameters to standard Montreal Neurological Institute space for volume and qMRI maps with SPM12s diffeomorphic algorithm based on exponentiated lie algebra (DARTEL) (Ashburner 2007). The GM probability maps for voxel-based morphometry analysis were scaled with the corresponding Jacobian determinants, whilst MT and R2* maps underwent the previously described weighted averaging (Draganski et al. 2011) to preserve the total signal average. Prior to statistical analysis all maps were spatially smoothed using an isotropic 3D Gaussian convolution kernel of 6 mm full-width-at-half-maximum.

Statistical analysis

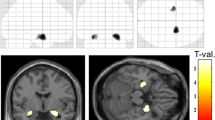

We concatenated whole-brain volume, MT saturation and R2* maps of left-lateralized TLE patients and healthy participants within a single multi-parametric ANOVA design to test for between-group differences (Fig. 1, Table 2A). Age, sex and total intracranial volume (TIV) were included as additional variables to control for their specific effects on brain anatomy. Using whole-brain and region-of-interest analyses, we tested correlations between brain morphometry, tissue properties and clinical phenotype—number of generalized seizures, disease duration and seizure-free interval preceding the MRI data acquisition (Figs. 2 and 4, Table 2B). For the post-hoc region-of-interest analysis testing the correlation between hippocampus volume/myelin content, seizure frequency and disease duration, we calculate the optimal weighted averages of TLE individuals’ hippocampal volumes using the first eigenvector as provided by SPM12’s volume-of-interest function. The spatial extent of the hippocampus was defined using the neuromorphometrics atlas (probabilistic and maximum probability tissue labels—derived from the “MICCAI 2012 Grand Challenge and Workshop on Multi-Atlas Labeling”, www.neuromorphometrics.com/2012_MICCAI_Challenge_Data.html).

Grey matter volume differences between left TLE patients and healthy controls. Statistical parametric maps (SPM) of grey matter volume differences between patients with left-lateralized TLE and healthy controls. SPMs displayed on axial T1-weighted image in standard MNI space. For visualization purposes SPMs thresholded at p < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons. TLE temporal lobe epilepsy, C healthy controls, L left, R right hemisphere

Correlation between seizure frequency and brain anatomy in left TLE patients. Statistical parametric maps (SPM) of positive correlation between A volume estimates and number of generalized seizures and between B myelin estimates based on MT saturation intensity values and number of generalized seizures in left TLE. Whole-brain results of SPM T statistics projected on axial T1-weighted image in standard MNI space on left side and on bilateral hippocampal surfaces on right side. For visualization purposes SPMs thresholded at p < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons. TLE temporal lobe epilepsy, MT magnetization transfer (saturation), L left, R right hemisphere

We report significant results at a statistical threshold of p < 0.05 after family-wise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons (Table 2) and as trends when below p < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Correlation between hippocampal grey matter volume and number of generalized seizures. Hippocampal volume estimates in left TLE patients (x axis) plotted against A number of generalized seizures (y axis); B MT saturation (x axis) and number of generalized seizures (y axis). Significant partial correlation for ipsilateral left hippocampus (p = 0.023) and for contralateral right hippocampus (p < 0.0001), correlation of MT parameters not significant (p > 0.05). Optimal weighted averages of hippocampal volumes extracted from left and right hippocampus. TLE temporal lobe epilepsy, C healthy controls, L left, R right, # number of

Results

Demographic and clinical phenotype

There were no significant sex-, age- or TIV-related differences between healthy controls and TLE patients. Five patients were ambidexter and one had a left-hand dominance (Table 1). The remaining 19 TLE patients were right-handed. The handedness (p = 0.54) and sex distribution (p = 0.34) of TLE patients were comparable to healthy controls.

Main effects of disease

We report a larger hippocampal volume bilaterally in TLE patients, additionally to operculum bilaterally, ipsilateral middle temporal gyrus and contralateral cerebellar and post-central regions (Fig. 1, Table 2A). There were no significant MT and R2* differences in the group comparison.

Seizure activity

The whole-brain VBM analysis showed a positive correlation between seizure frequency, measured by number of generalized seizures, and the volume of hippocampus bilaterally (Fig. 2A, Table 2B). We denote the higher statistical significance confined to the anterior hippocampus. We point out that the region denoted as hippocampal tail in the voxel-based analysis may include also parts of the fornix. There was a similar effect for the contralateral transverse temporal gyrus and thalamus, the ipsilateral posterior insula, orbito-frontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and cerebellar posterior lobes bilaterally. The VBQ analysis demonstrated spatially overlapping results with a positive correlation between MT saturation and seizure activity in the ipsilateral hippocampal body, bilateral thalamus and the contralateral transverse temporal gyrus (Fig. 2B, Table 2B).

The post-hoc region-of-interest analysis centered on the hippocampus (Fig. 1) confirmed the correlation between number of generalized seizures (Fig. 2) with hippocampus volume bilaterally with emphasis on the right hippocampus (Figs. 1 and 3A). The MT saturation analysis did not show significant correlations (Fig. 3B).

Disease progression

The VBQ analysis revealed a positive correlation between disease duration and R2* increase, indicative for iron content of the ipsilateral hippocampus, the transverse temporal gyrus and cerebellum as well as contralateral insula and basal ganglia (Fig. 4A). In contrast, seizure-free intervals correlated negatively with R2* values in the ipsilateral parahippocampal gyrus and the contralateral fusiform gyrus (Fig. 4C).

Correlation between disease progression, seizure-free interval and iron content. Statistical parametric maps of positive and negative correlation between effective transverse relaxation rate R2* intensity values and A disease duration in years (with values projected on bilateral hippocampal surfaces left) and B the seizure-free interval in months in left TLE. Results displayed on T1-weighted image in MNI space, statistical threshold at p < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons. [−] negative, [ +] positive correlation, L left, R right

Discussion

Our study demonstrates a specific pattern of volume and brain tissue property differences in TLE patients that were associated with individuals’ disease duration and seizure frequency. The observed hippocampal volume expansion in TLE patients is paralleled by MT saturation increase in the very same region. Differences in mesial temporal lobe volume and tissue properties were associated with individuals’ seizure activity. Our qMRI multi-parameter approach extends previous morphometry findings in patients with TLE to show concomitant microstructure differences that are interpreted in the context of underlying neurobiological processes.

Seizure activity associated with differences in regional volume and myelin content

Our main finding is that seizure activity and TLE disease duration impact hippocampal microstructure beyond the already known effects on volume and shape. The effects are bilateral, thus independent from seizure focus localization. This finding is at odds with the imaging neuroscience literature that reports volume loss interpreted in the context of hippocampal sclerosis, which can be seen in chronic cases even with the naked eye. There are two lines of argumentation that support the notion of initial volume increase in the early phase of TLE—one related to the underlying neurobiological processes and another—to methodological and interpretational issues of computational anatomy studies using T1-weighted imaging.

We interpret the hippocampal volume increase in the early phase of TLE as indicative for seizure-induced boost of neurogenesis potentially paralleled by mossy fiber sprouting and changes in density/persistence of hilar basal dendrites. This assumption is based on the cumulating evidence from animal TLE models (Sierra et al. 2015a, b) and from findings in both animal model (Madsen et al. 2000; Olesen et al. 2017) and investigations in patients treated with electro-convulsive therapy (Dukart et al. 2014). A particular detail – the gradient of seizure impact along the longitudinal hippocampal axis with stronger effects in the anterior hippocampus, seen after electro-convulsive therapy (Dukart et al. 2014) and in our study—in the correlation analysis with seizure frequency, lends further credibility to our findings. For the chronic phase of TLE, hippocampal atrophy, due to depletion of the stem cell pool and ongoing asymmetric cell division with predominant generation of astrocytes (Sierra et al. 2015a, b), can explain the widely accepted radiological and histology findings.

The second line of argumentation addressing the controversy in the computational anatomy literature about TLE-induced brain structure differences in patients (Bernhardt et al. 2013b; Briellmann et al. 2002; Coan et al. 2014; Holtkamp et al. 2004; Mueller et al. 2006) stems from the fact that the majority of studies use T1-weighted imaging for assessment of volume or cortical thickness. Independent from the methods used for feature extraction and statistical analysis—i.e. surface- or voxel-based, the fact that the MR contrast is dependent on underlying tissue properties and that T1-weighted MRI protocols are not informative with respect to these changes, prompted a revision of the established neurobiological interpretation. Recent evidence about the occasional “erroneous” interpretation of nature and directionality of morphometric changes is provided in the context of brain maturation (Natu et al. 2019) and ageing (Lorio et al. 2016b; Taubert et al. 2020). Our volume estimates are based on qMRI data, which renders them more robust to the underlying tissue property characteristics in the context of TLE (Lorio et al. 2016b).

The novelty of our VBQ approach comes from the analysis of parameters indicative for tissue property differences, beyond and above the morphometry findings. The observed positive correlation between MT saturation and seizure frequency restricted to the hippocampus ipsilateral to seizure onset can be interpreted in the context of neurogenesis and related biological phenomena. Given the fact that MT saturation is based on differences in macromolecular content rather than in molecular mobility, it allows for the distinction of densely packed gray matter from normal gray and white matter but is also sensitive to tissue’s myelin content (Draganski et al. 2011; Helms et al. 2008). We interpret the MT saturation findings as correlates of axonal sprouting of existing and newly generated neurons in the ipsilateral to seizure onset hippocampus, most probably secondary to seizures (Savaskan and Nitsch 2001) or as an additional marker of increased neurogenesis,—i.e. cellular density.

Disease progression related to iron concentration estimates

The observed positive correlation between the transverse relaxation rate—R2* and disease duration is interpreted as iron accumulation, inflammation, edema or blood leakage. Iron accumulation confined to the mesial temporal lobe of TLE patients is supported by previous studies suggesting a seizure-dependent activation of an inflammatory cascade involving IL-6 and TNF-α cytokines leading to altered iron transfer and saturation (Ikeda 2001; Tombini et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014). In patients with epilepsy, transferrin saturations are increased as a surrogate marker for iron overload (Ikeda 2001) and the presence of altered iron suggests dysfunctional regeneration after seizure. In line with a previous study, our findings support the interpretation that a seizure-induced increase of the permeability of the blood–brain-barrier leads to extravasation of blood components and hemoglobin with the consequence of ferritin overexpression in the hippocampus (Gorter et al. 2005). Another argument for the role of iron in TLE patients is the fact that in the animal model, iron chelators ameliorate seizure-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress, excitotoxic neuronal injury and hippocampal cell loss (Liang et al. 2008). Alternatively, one can assume that volume and qMRI parameters could be influenced by vasogenic or cytotoxic edema after generalized seizures (Scott et al. 2006). Given the mean of seizure-free intervals of 46 months with a minimum interval of two months, the probability of seizure-induced impact on the presented results is negligible.

We acknowledge potential study limitations that could impact our results and interpretations. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits our inferences to correlation rather than causation. Given the novelty of the neuroimaging approach, we focused on a rather small clinical cohort with unilateral left-sided seizure onset. Epilepsy severity is inferred from subjective reports of seizures with secondary generalization. Subjective seizure diaries only give a restricted insight into individual real seizure activity. The current approach focuses exclusively on seizures with generalization as determinants of temporal lobe changes. Focal seizures without generalization were not considered in the analysis. Histological interpretation of the MT and R2* maps are based on references studies (Helms et al. 2008), however building on validated biophysical models.

Conclusion

Our combined VBM/VBQ study offers additional neurobiological interpretation linking disease duration, seizure frequency, brain volume and tissue properties in pharmaco-responsive and -resistant TLE patients. We interpret our results as evidence for a seizure-induced boost of neurogenesis and axonal sprouting associated with myelination, which is followed by a continuous, but reversible accumulation of iron in the mesial temporal lobe. Non-invasive assessment of brain tissue properties could become relevant for the clinical evaluation and outcome prediction in TLE.

Key Points

-

qMRI biomarkers of brain tissue microstructure are correlates of TLE clinical phenotype providing insight into microscopic processes underlying disease

-

We investigate qMRI in TLE patients and healthy controls by MT saturation and effective transverse relaxation rate, biomarkers of myelin and iron concentration

-

Seizure activity correlates with MT saturation measures in ipsilateral hippocampus paralleled by volume differences in same area

-

Disease duration correlates positively with R2* measures in mesial temporal lobe, while seizure freedom is associated with decrease of R2* in very same region

-

Clinical phenotype characteristics are linked to processes involving myelination and iron differences in mesial temporal lobe structures

Availability of data and material

The data is currently not available online. Anonymized data is available on demand.

Code availability

The used code is publicly available including: SPM 12 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12) with voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and the current version of the VBQ toolbox (https://hmri-group.github.io/hMRI-toolbox/) running under Matlab 7.13 (Mathworks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA).

Abbreviations

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- FEW:

-

Family-wise error

- GM:

-

Grey matter

- MT:

-

Magnetization transfer

- SPM:

-

Statistical parametric mapping

- TLE:

-

Temporal lobe epilepsy

- qMRI:

-

Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging

- VBM:

-

Voxel-based morphometry

- VBQ:

-

Voxel-based quantification

References

Aggarwal M, Li X, Grohn O, Sierra A (2018) Nuclei-specific deposits of iron and calcium in the rat thalamus after status epilepticus revealed with quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 47:554–564. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.25777

Ashburner J (2007) A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 38:95–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007

Ashburner J, Friston KJ (2005) Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26:839–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018

Berg AT et al (2010) Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 51:676–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x

Bernhardt BC, Hong S, Bernasconi A, Bernasconi N (2013a) Imaging Structural and Functional Brain Networks in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Front Hum Neurosci 7:624. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00624

Bernhardt BC, Kim H, Bernasconi N (2013b) Patterns of subregional mesiotemporal disease progression in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 81:1840–1847. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000436069.20513.92

Bernhardt BC et al (2018) Preferential susceptibility of limbic cortices to microstructural damage in temporal lobe epilepsy: a quantitative T1 mapping study. Neuroimage 182:294–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.002

Bonilha L, Rorden C, Castellano G, Pereira F, Rio PA, Cendes F, Li LM (2004) Voxel-based morphometry reveals gray matter network atrophy in refractory medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 61:1379–1384. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.61.9.1379

Briellmann RS, Berkovic SF, Syngeniotis A, King MA, Jackson GD (2002) Seizure-associated hippocampal volume loss: a longitudinal magnetic resonance study of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 51:641–644. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10171

Coan AC, Campos BM, Yasuda CL, Kubota BY, Bergo FP, Guerreiro CA, Cendes F (2014) Frequent seizures are associated with a network of gray matter atrophy in temporal lobe epilepsy with or without hippocampal sclerosis. PLoS ONE 9:e85843. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085843

Draganski B, Ashburner J, Hutton C, Kherif F, Frackowiak RS, Helms G, Weiskopf N (2011) Regional specificity of MRI contrast parameter changes in normal ageing revealed by voxel-based quantification (VBQ). Neuroimage 55:1423–1434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.052

Duffy BA, Choy M, Riegler J, Wells JA, Anthony DC, Scott RC, Lythgoe MF (2012) Imaging seizure-induced inflammation using an antibody targeted iron oxide contrast agent. Neuroimage 60:1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.048

Dukart J et al (2014) Electroconvulsive therapy-induced brain plasticity determines therapeutic outcome in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:1156–1161. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321399111

Garbelli R et al (2012) Blurring in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy: clinical, high-field imaging and ultrastructural study. Brain 135:2337–2349. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws149

Gorter JA, Mesquita AR, van Vliet EA, da Silva FH, Aronica E (2005) Increased expression of ferritin, an iron-storage protein, in specific regions of the parahippocampal cortex of epileptic rats. Epilepsia 46:1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.11505.x

Helms G, Dechent P (2009) Increased SNR and reduced distortions by averaging multiple gradient echo signals in 3D FLASH imaging of the human brain at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 29:198–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.21629

Helms G, Dathe H, Kallenberg K, Dechent P (2008) High-resolution maps of magnetization transfer with inherent correction for RF inhomogeneity and T1 relaxation obtained from 3D FLASH. MRI Magn Reson Med 60:1396–1407. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21732

Holtkamp M, Schuchmann S, Gottschalk S, Meierkord H (2004) Recurrent seizures do not cause hippocampal damage. J Neurol 251:458–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-004-0356-9

Hutton C, Balteau E, Lutti A, Josephs O, Weiskopf N (2012) Modelling temporal stability of EPI time series using magnitude images acquired with multi-channel receiver coils. PLoS ONE 7:e52075. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052075

Ikeda M (2001) Iron overload without the C282Y mutation in patients with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 70:551–553

Kasper BS, Paulus W (2004) Perivascular clustering in temporal lobe epilepsy: oligodendroglial cells of unknown function. Acta Neuropathol 108:471–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-004-0914-3

Kwan P et al (2010) Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia 51:1069–1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x

Liang LP, Jarrett SG, Patel M (2008) Chelation of mitochondrial iron prevents seizure-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal injury. J Neurosci 28:11550–11556. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3016-08.2008

Lorio S et al (2016a) New tissue priors for improved automated classification of subcortical brain structures on MRI. Neuroimage 130:157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.062

Lorio S et al (2016b) Neurobiological origin of spurious brain morphological changes: a quantitative MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 37:1801–1815. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23137

Luo Y, Hu Q, Zhang Q, Hong S, Tang X, Cheng L, Jiang L (2015) Alterations in hippocampal myelin and oligodendrocyte precursor cells during epileptogenesis. Brain Res 1627:154–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.027

Lutti A et al (2012) Robust and fast whole brain mapping of the RF transmit field B1 at 7T. PLoS ONE 7:e32379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032379

Lutti A, Dick F, Sereno MI, Weiskopf N (2014) Using high-resolution quantitative mapping of R1 as an index of cortical myelination. Neuroimage 93(Pt 2):176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.005

Madsen TM, Treschow A, Bengzon J, Bolwig TG, Lindvall O, Tingstrom A (2000) Increased neurogenesis in a model of electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiat 47:1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00228-6

Mueller SG, Laxer KD, Cashdollar N, Buckley S, Paul C, Weiner MW (2006) Voxel-based optimized morphometry (VBM) of gray and white matter in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) with and without mesial temporal sclerosis. Epilepsia 47:900–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00512.x

Natu VS et al (2019) Apparent thinning of human visual cortex during childhood is associated with myelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:20750–20759. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1904931116

Oldfield RC (1971) The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4

Olesen MV, Wortwein G, Folke J, Pakkenberg B (2017) Electroconvulsive stimulation results in long-term survival of newly generated hippocampal neurons in rats. Hippocampus 27:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22670

Ozdogmus O, Cavdar S, Ersoy Y, Ercan F, Uzun I (2009) A preliminary study, using electron and light-microscopic methods, of axon numbers in the fornix in autopsies of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Anat Sci Int 84:2–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12565-008-0001-2

Savaskan NE, Nitsch R (2001) Molecules involved in reactive sprouting in the hippocampus. Rev Neurosci 12:195–215

Scharfman HE, Goodman JH, Sollas AL (2000) Granule-like neurons at the hilar/CA3 border after status epilepticus and their synchrony with area CA3 pyramidal cells: functional implications of seizure-induced neurogenesis. J Neurosci 20:6144–6158

Scott RC, King MD, Gadian DG, Neville BG, Connelly A (2006) Prolonged febrile seizures are associated with hippocampal vasogenic edema and developmental changes. Epilepsia 47:1493–1498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00621.x

Sierra A, Grohn O, Pitkanen A (2015a) Imaging microstructural damage and plasticity in the hippocampus during epileptogenesis. Neuroscience 309:162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.054

Sierra A et al (2015b) Neuronal hyperactivity accelerates depletion of neural stem cells and impairs hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 16:488–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.003

Stefanits H, Czech T, Pataraia E, Baumgartner C, Derhaschnig N, Slana A, Kovacs GG (2012) Prominent oligodendroglial response in surgical specimens of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Clin Neuropathol 31:409–417

Sutula TP (2004) Mechanisms of epilepsy progression: current theories and perspectives from neuroplasticity in adulthood and development. Epilepsy Res 60:161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2004.07.001

Taubert M et al (2020) Converging patterns of aging-associated brain volume loss and tissue microstructure differences. Neurobiol Aging 88:108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.01.006

Thom M et al (2000) Microdysgenesis with abnormal cortical myelinated fibres in temporal lobe epilepsy: a histopathological study with calbindin D-28-K immunohistochemistry. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 26:251–257

Tombini M et al (2013) Inflammation and iron metabolism in adult patients with epilepsy: does a link exist? Epilepsy Res 107:244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.09.010

van Vliet EA, da Costa AS, Redeker S, van Schaik R, Aronica E, Gorter JA (2007) Blood-brain barrier leakage may lead to progression of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain 130:521–534. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl318

Weiskopf N et al (2013) Quantitative multi-parameter mapping of R1, PD(*), MT, and R2(*) at 3T: a multi-center validation. Front Neurosci 7:95. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00095

Wellmer J, Quesada CM, Rothe L, Elger CE, Bien CG, Urbach H (2013) Proposal for a magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the detection of epileptogenic lesions at early outpatient stages. Epilepsia 54:1977–1987. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12375

Ye Y et al (2013) Altered hippocampal myelinated fiber integrity in a lithium-pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy: a histopathological and stereological investigation. Brain Res 1522:76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2013.05.026

Ye Q, Zeng C, Dong L, Wu Y, Huang Q, Wu Y (2019) Inhibition of ferroptosis processes ameliorates cognitive impairment in kainic acid-induced temporal lobe epilepsy in rats. Am J Transl Res 11:875–884

Zhang Z et al (2014) Brain iron redistribution in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. BMC Neurosci 15:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-014-0117-3

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all volunteers for their participation in the study and Lester Melie-Garcia for support on MRI data preprocessing.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 720270 (HBP SGA1). This work was carried out on the MRI platform of the Département des Neurosciences Cliniques—Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), which is generously supported by the ROGER DE SPOELBERCH and Partridge Foundations. AL is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No 320030_184784) and the ROGER DE SPOELBERCH Foundation. MS is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project Grants 163398 and 180365). BD is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (NCCR Synapsy, project Grant No. 32003B_135679, 32003B_159780, 324730_192755 and CRSK-3_190185) and the Leenaards Foundation. BD and ER are supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SPUM 33CM30_140332/1). FK received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and the MORPHEMIC Grant (Grant No. 871643).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee, the Cantonal Commission on Ethics in Human Research Vaud, Lausanne.

Consent to participate and for publication

Prior to study inclusion, we obtained written informed consent from each participant to participate in the study and to allow publication of the collected anonymized data. All procedures were performed in accordance with national and international guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roggenhofer, E., Toumpouli, E., Seeck, M. et al. Clinical phenotype modulates brain’s myelin and iron content in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Struct Funct 227, 901–911 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-021-02428-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-021-02428-z