Abstract

Purpose

To assess the influence of low skeletal muscle mass (LSMM) on post-operative complications in patients with hepatic malignancies grade (Clavien Dindo ≥ 3) undergoing resection.

Methods

MEDLINE, Cochrane, and SCOPUS databases were screened for associations between sarcopenia and major post-operative complications (≥ grade 3 according to Clavien-Dindo classification) after resection of different malignant liver tumors. RevMan 5.3 software was used to perform the meta-analysis. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed according to the QUIPS instrument.

Results

The analysis included 17 studies comprising 3157 patients. Subgroup analyses were performed for cholangiocarcinoma (CCC), colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastases, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). LSMM as identified on CT was present in 1260 patients (39.9%). Analysis of the overall sample showed that LSMM was associated with higher post-operative complications grade Clavien Dindo ≥ 3 (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.25–1.95, p < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, LSMM was associated with post-operative complications in CRC metastases (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.11–2.32, p = 0.01). In HCC and CCC sub-analyses, LSMM was not associated with post-operative complications in simple regression analysis.

Conclusion

LSMM is associated with major post-operative complications in patients undergoing surgery for hepatic metastases and it does not influence major post-operative complications in patients with HCC and CCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sarcopenia has been found to be an indicator of poor prognosis in oncologic diseases. It is defined as the loss of or low muscle mass, low muscle strength, and impaired muscle quality [1]. Commonly used indicators for sarcopenia are low skeletal muscle mass (LSMM) and muscle density, both of which can be assessed on computed tomography (CT) scans [2]. LSMM has been associated with poorer survival in malignancies such as gastric and esophageal cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and lymphoma, among others [3,4,5,6,7]. It has also been associated with dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) and with higher rates of cardiac and pulmonary complications in oncologic patients [8, 9]. For post-operative outcomes, a negative influence for post-operative LSMM has been shown for extrahepatic cancer entities [10,11,12].

The influence of LSMM on post-operative complications for cancer patients has been shown in meta-analyses for gastric cancer (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.53–3.08) [13] and colorectal cancer (OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 0.36–2.44) [14]. In esophageal cancer, pre-operative LSMM was associated with higher rates of post-operative pulmonary complications (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.32–3.119), but not with higher rates of complications as defined by Clavien Dindo (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.81) [15, 16]. No association with overall post-operative complications was found in a meta-analysis for pancreatic cancer (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.78–1.19), yet sarcopenic patients showed higher peri-operative mortality (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.19–4.85) [17].

The impact of LSMM on patient outcome after surgery for hepatic malignancies is not yet clear. For most primary and secondary liver tumors, surgical resection is the cornerstone of curative treatment approaches. However, liver resections remain major surgical procedures and are still associated with relevant post-operative morbidity and mortality and careful patient selection remains crucial in order to improve patient outcome [18, 19]. Prognostic indicators for patient outcome after liver surgery are wanted. It is known that age, performance status, comorbidities, and lymph node status, among others, influence post-operative complications and outcome [20, 21]. However, discriminatory accuracy of prognostic scores has been limited [22].

The aim of this study is to systematically assess the influence of LSMM on patient post-operative outcomes (grade Clavien Dindo ≥ 3) after hepatic resection for primary and secondary liver malignancies.

Methods

Search strategy

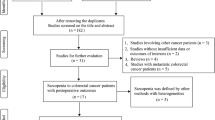

For the present analysis, we performed a search within MEDLINE library, Cochrane, SCOPUS, and Web of Science data bases using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) (Fig. 1) [23]. The search was performed according to the recommendation for literature search in surgical systematic reviews [24]. Occurrence of major (≥ grade 3 according to Clavien-Dindo classification) postoperative complications after resection of different malignant liver tumors was the endpoint of the present meta-analysis.

The following search criteria were used: “sarcopenia OR low skeletal muscle mass OR body composition OR skeletal muscle index AND liver AND postoperative complications OR postoperative complication.” The last search was performed in March 2022. Inclusion criteria for the articles were as follows:

-

original investigations with humans;

-

patients with malignant hepatic tumors treated by surgical resection;

-

estimation of presurgical LSMM/sarcopenia;

-

reported data about influence of LSMM/sarcopenia on occurrence of postoperative complications (odds ratios and 95% CI’s).

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

review articles, case reports, and letters;

-

non-English language;

-

experimental studies;

-

missing of statistical data regarding influence of LSMM/sarcopenia on occurrence of postoperative complications (odds ratios and 95% CI’s).

Data extraction

At first, the abstracts were checked. Duplicate articles, review articles, experimental studies, case reports, and non-English publications were excluded. Furthermore, the full texts of the remaining articles were analyzed. Studies with no sufficient data were excluded. The remaining articles met the inclusion criteria. The following data were acquired for the analysis: authors, year of publication, type of tumors, number of patients, prevalence of LSMM/sarcopenia, and statistical data about influence of LSMM/sarcopenia on outcomes (odds ratios and 95% CI’s).

Meta-analysis

Three observers (AS, MT and AW) in consensus analyzed the methodological quality of the included 17 studies according to the Quality in Prognosis Studies Instrument (QUIPS) instrument [25]. Risk of bias of studies was considered low if ≤ 2 items were rated “low risk” or “moderate risk.” Risk of bias was considered high if ≥ 1 item was rated “high risk.” Furthermore, a funnel plot was constructed to analyze a possible publication bias and asymmetry was quantified by using the Egger test [26]. p value of less than 0.05 indicated publication bias.

The RevMan 5.3 (Computer program, version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Center, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used [27, 28]. Heterogeneity was calculated by means of the index I2. DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models with inverse-variance weights were performed [29].

Results

Description of included studies

According to the search strategy, 870 records were initially identified. After exclusion of duplicate records, 102 studies were screened. Records that did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 73), reviews, and those not related to the topic under investigation were excluded. Of the remaining 29 studies, 12 did not report sufficient results. Ultimately, 17 studies with 3157 patients were included in our analysis (Fig. 1). Of these, five studies were from Asia (4 from Japan, one from China), ten from Europe (three from Germany, two from France, one from Austria, one from Sweden, one from the Netherlands, one from Italy, one from Switzerland), and two were from the USA. Included studies were published between 2011 and 2022. All studies were retrospective in nature.

The assessed liver malignancies were as follows: cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) (2 studies, 176 patients), colorectal liver metastases (6 studies, 1188 patients), HCC (6 studies, 1108 patients), and different primary and secondary hepatic malignancies (3 studies, 685 patients). Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Altogether, there were 2058 men (64.4%) and 1139 women (35.6%) included in the studies. The Egger test did not identify a publication bias among the included articles (p = 0.10).

According to the QUIPS checklist, 16/17 (94.1%) studies had an overall low risk of bias. A high risk of bias was assigned to one study due to a possible bias in patient selection criteria (Fig. 2). No studies were excluded due to a risk of bias.

Assessment of LSMM

Most studies used the skeletal muscle index (SMI) at the level of the third lumbar vertebra to measure LSMM (14 studies, 82.4%). One study (5.9%) used a combination of SMI and muscle strength to define LSMM [30]. The total psoas area (TPA) and the total psoas volume (TPV) were applied in one study, respectively [31, 32].

LSMM as identified by pre-operative CT scans was identified in 1260 patients (39.9%). In the subgroup analysis, the rate of sarcopenic patients ranged from 31.8% in the HCC cohort to 58.0% in the CCC cohort.

Meta-analysis for major post-operative complications

Regression of the aggregated data showed that across all studies, LSMM was associated with higher major post-operative complications (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.25–1.95, p < 0.001). The studies showed a high heterogeneity (I2 = 62%) (Fig. 3).

In the subgroup analyses, the influence of LSMM for the different tumor entities was analyzed.

In CCC, simple regression did not show an association between LSMM and major complications (OR 1.64, 95% CI 0.71–3.76, p = 0.25). There was no heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4b).

In HCC, an association between pre-operative LSMM and major post-operative complications was as follows: OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.61–3.09, p = 0.45. There was high heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 82%) (Fig. 4a).

In colorectal liver metastases, simple regression showed that LSMM was associated with higher post-operative complications (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.11–2.32, p = 0.01). There was no heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis assessing the impact of LSMM on major post-operative complications after hepatic resection for various hepatic malignancies in a large sample. It is shown that pre-operative LSMM is associated with higher rates of major complications in patients with hepatic malignancies undergoing hepatic resection.

The importance of LSMM for oncologic patients has been underlined for various clinical features. It has been shown that LSMM is associated with higher rates of post-operative cardiac and pulmonary complications in gastric cancer patients [9]. In non-small-cell lung cancer, patients with LSMM undergoing surgery had a lower 5-year OS and a lower disease-free survival rate [33]. An association between LSMM and dose limiting toxicity in oncologic patients has also been identified [8]. Metabolism of anti-cancer drugs may also be affected [34, 35]. It has been reported that LSMM is associated with elevated intracellular inflammation, oxidative stress, and high protein consumption [1, 36].

Previous meta-analyses have found an association of LSMM with OS after local therapy for CRC liver metastases [20]. For instance, Levolger et al. found poorer OS in patients with LSMM undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies [37]. Trejo-Avila et al. reported an association between LSMM and worse post-operative OS in patients with CRC [38]. Xu et al. found shorter post-operative OS in HCC patients undergoing hepatectomy [39]. Simonsen et al. identified LSMM as an increased risk for post-operative complications after surgery for gastrointestinal cancer [40]. However, a sub-analysis did not find an association between LSMM and post-operative complications after surgery for CRC liver metastases (RR 1.91, 95% CI 0.97–3.75). The fact that their analysis included only two studies [31, 41] and a low number of patients may explain the different results compared to our analysis. Also, no significant association was found for liver cancer (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.92–1.71).

With regard to complications after surgery, an association between LSMM and post-operative outcomes according to the Clavien Dindo score was reported for cancer patients after gastrectomy (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.53–3.08) [13] and surgery for colorectal cancer (OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.36–2.44) [14]. Single studies have found LSMM to be associated with post-operative complications for pancreatic cancer [42], yet a meta-analysis did not find a significant association (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.78–1.19) [17]. However, patients with LSMM showed a higher peri-operative mortality after pancreatic surgery (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.19–4.85) [17]. Similarly, in esophageal cancer, no significant influence of LSMM on post-operative complications as defined by the Clavien Dindo grading was found (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.81), yet patients with LSMM exhibited higher rates of respiratory complications [15, 16]. It was also found that patients with LSMM had higher rates of nosocomial infections after colectomy [43]. In HCC, one study found higher rates of post-operative complications in patients having undergone either hepatic resection or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [12, 44]. In patients undergoing liver resection, patients with LSMM exhibited smaller preoperative total functional liver volume [45, 46]. Cao et al. reported that different measures of LSMM, such as SMI and PMI, can predict major post-operative complications following surgery for hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies [47]. In a meta-analysis by Zhang et al. including patients undergoing treatment for primary hepatic malignancies, the rate of major complications according to Clavien Dindo ≥ 3 was not associated with the presence of LSMM [48].

In the present study, the association of LSMM with major post-operative complications was significant, yet discrete, in the aggregate analysis. A significant association was found only for CRC liver metastases in the subgroup analysis. In HCC and CCC sub-analyses, no significant impact of sarcopenia was found. The impact of sarcopenia did not differ significantly between primary hepatic malignancies and metastases. Of the studies combining different malignancies [30, 32, 49], two did not refer to SMI as a measure of sarcopenia alone, but Berardi et al. used the combination of reduced muscle mass and strength as a definition of LSMM, while Valero et al. applied TPA and TPV. Our overall results exhibit a somewhat lower OR for post-operative complications for liver resection than those published for gastrectomy or surgery for CRC [13, 14].

In our analysis, LSMM was only associated with major post-operative complications in patients with CRC liver metastases. The reason for this remains unknown. We hypothesize that the number of lesions resected is higher in liver metastases than in primary liver tumors. However, the number of lesions resected is often not indicated in the studies so that a detailed analysis is not possible.

Of the included 17 studies in our analysis, only seven studies detailed the kind of complications that occurred after surgery. The most common surgical complications were intraabdominal abscesses and biliary leakages [32, 41, 50,51,52]. Peng et al. reported post-operative bleeding as the most frequent surgical complication, while ascites was the most common complication in Berardi et al. [30, 31]. Among non-surgical complications, respiratory complications including pneumonia and cardiovascular complications were most frequently mentioned [41, 50, 51, 53]. Pleural effusion requiring drainage was the most common cited complication in the study by Peng et al. [31]. Due the low number of studies giving details on the category of complications, no sub-analysis was performed.

The present study adds to the evidence that LSMM is associated with major post-operative complications in cancer patients. The novelty of the present work is that for the first time a selective analysis of post-operative complications after surgery for different liver tumors was performed. This sub-analysis for different entities was not performed in other meta-analyses. The fractions of patients with LSMM in our studies are within the ranges reported for cancer patients in the literature [12, 54, 55]. The prevalence of LSMM differed depending on tumor entity, with HCC showing the lowest rate (29.6%) and CCC the highest rate (58.0%). It must be noted, however, that heterogeneity in the overall sample was relatively high at 62%. This is due to the low number of studies involved and heterogeneous tumor entities. This may affect the generalization of our results. Nevertheless, our findings implicate importance for the daily clinical practice.

Measurements of LSMM are easy to acquire as most patients undergo routine staging CT scans prior to surgery. Unlike other factors influencing survival, LSMM is a modifiable factor. Early identification is important and may induce treatment and improve patient outcomes. The literature has shown that the vulnerability of patients with LSMM/sarcopenia stems from limited mobility as well as from distorted metabolic and physiological pathways. Patients with LSMM have activated systemic inflammatory pathways and might have increased metabolic activity, leading to inflammation and muscle wasting [56]. Skeletal muscle has both endocrine and paracrine functions that may be inhibited by LSMM [57]. Some of these myokines may possess anti-neoplastic effect and suppress tumorigenesis [58, 59]. Thus, multimodal interventions, including supervised physical exercise and improving nutritional status, may potentially inhibit cancer cell division in patients with LSMM and improve quality of life [60]. There is increasing evidence that physical training in oncologic patients can improve muscle function [61, 62]. At the same time, dietary supplements and high protein diet may prevent the loss of muscle mass [63].Yamamoto et al. have shown that pre-operative exercise and nutritional supplementation may reduce sarcopenia and improve post-operative outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for gastric cancer [62]. For head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC), Kabarriti et al. reported improved survival (non-significant) and reduced disease progression following an additive nutritional program [64]. The two may also be intertwined, as Yokoyama et al. reported a correlation between physical activity and nutritional status before hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery [65]. Also, Kelly et al. have shown that post-operative complications represent a major risk factor for hospital readmissions after gastrointestinal surgery [66]. This can potentially be reduced by preventive interventions. Physical exercise and nutritional supplementation should be started early in the disease process and intensified prior to surgery to potentially improve outcomes. Further research will be necessary to determine the best training and nutritional protocol for patients with LSMM before surgery.

Our analysis has several limitations that need to be addressed. All studies included were retrospective. Some suffered from selection bias. We included studies in English language only. While the total number of studies screened was high, subgroup analyses may suffer from the low number of studies available. The articles included tumors of different entities and at different stages with varying surgical procedures, being reflected by the high heterogeneity of the studies in the aggregate analysis. Furthermore, definitions and measurements of LSMM were different among included studies (Table 1). Most studies in our analysis measured LSMM by means of CT, while one study used a combination of CT and handgrip strength. While CT is considered the gold standard, correlation between different methods of assessing sarcopenia is low, as was recently reported in a study by Simonsen et al. [67].

In conclusion, our meta-analysis showed that LSMM is a discrete but significant factor of post-operative complications in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal liver metastases. The presence of LSMM should be specifically mentioned in medical reports in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Addressing sarcopenia could potentially improve outcome in this patient group. LSMM does not influence major post-operative complications in patients with HCC and CCC.

Abbreviations

- CCC:

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

- CRC:

-

Colorectal carcinoma

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DLT:

-

Dose limiting toxicity

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- LSMM:

-

Low skeletal muscle mass

- PMI:

-

Psoas muscle index

- QUIPS:

-

Quality in prognosis studies instrument

- SMI:

-

Skeletal muscle index

- TPA:

-

Total psoas area

- TPV:

-

Total psoas volume

References

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J et al (2019) Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48:16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

Marcus RL, Addison O, Kidde JP et al (2010) Skeletal muscle fat infiltration: impact of age, inactivity, and exercise. J Nutr Health Aging 14:362–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-010-0081-2

Sun G, Li Y, Peng Y et al (2018) Can sarcopenia be a predictor of prognosis for patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 33:1419–1427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3128-1

Deng H-Y, Zha P, Peng L et al (2019) Preoperative sarcopenia is a predictor of poor prognosis of esophageal cancer after esophagectomy: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 32. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doy115

Mintziras I, Miligkos M, Wächter S et al (2018) Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity are significantly associated with poorer overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 59:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.09.014

Karmali R, Alrifai T, Fughhi IAM et al (2017) Impact of cachexia on outcomes in aggressive lymphomas. Ann Hematol 96:951–956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-017-2958-1

Camus V, Lanic H, Kraut J et al (2014) Prognostic impact of fat tissue loss and cachexia assessed by computed tomography scan in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Eur J Haematol 93:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12285

Surov A, Pech M, Gessner D et al (2021) Low skeletal muscle mass is a predictor of treatment related toxicity in oncologic patients. A meta-analysis Clin Nutr 40:5298–5310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.08.023

Kamarajah SK, Bundred J, Tan BHL (2019) Body composition assessment and sarcopenia in patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 22:10–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0882-2

Fukuda Y, Yamamoto K, Hirao M et al (2016) Sarcopenia is associated with severe postoperative complications in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer 19:986–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0546-4

Zhuang C-L, Huang D-D, Pang W-Y et al (2016) Sarcopenia is an independent predictor of severe postoperative complications and long-term survival after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Med (Baltimore) 95:e3164. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003164

Pamoukdjian F, Bouillet T, Lévy V et al (2018) Prevalence and predictive value of pre-therapeutic sarcopenia in cancer patients: a systematic review. Clin Nutr 37:1101–1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2017.07.010

Yang Z, Zhou X, Ma B et al (2018) Predictive value of preoperative sarcopenia in patients with gastric cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg 22:1890–1902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-018-3856-0

Xie H, Wei L, Liu M et al (2021) Preoperative computed tomography-assessed sarcopenia as a predictor of complications and long-term prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 406:1775–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02274-x

Boshier PR, Heneghan R, Markar SR et al (2018) Assessment of body composition and sarcopenia in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 31:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doy047

Papaconstantinou D, Vretakakou K, Paspala A et al (2020) The impact of preoperative sarcopenia on postoperative complications following esophagectomy for esophageal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 33:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doaa002

Bundred J, Kamarajah SK, Roberts KJ (2019) Body composition assessment and sarcopenia in patients with pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB 21:1603–1612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2019.05.018

Virani S, Michaelson JS, Hutter MM et al (2007) Morbidity and mortality after liver resection: results of the patient safety in surgery study. J Am Coll Surg 204:1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.067

Jin S (2013) Management of post-hepatectomy complications. World J Gastroenterol 19:7983. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.7983

Waalboer RB, Meyer YM, Galjart B et al (2021) Sarcopenia and long-term survival outcomes after local therapy for colorectal liver metastasis: a meta-analysis. HPB. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2021.08.947

Chang C-M, Yin W-Y, Su Y-C et al (2014) Preoperative risk score predicting 90-day mortality after liver resection in a population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore) 93:e59. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000059

Roberts KJ, White A, Cockbain A et al (2014) Performance of prognostic scores in predicting long-term outcome following resection of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 101:856–866. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9471

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535–b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Kalkum E, Klotz R, Seide S et al (2021) Systematic reviews in surgery-recommendations from the Study Center of the German Society of Surgery. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 406:1723–1731. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00423-021-02204-X

Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL et al (2013) Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 158:280–286. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Leeflang MMG (2008) Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med 149:889. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00008

Zamora J, Abraira V, Muriel A et al (2006) Meta-DiSc: a software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Med Res Methodol 6:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-31

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

Berardi G, Antonelli G, Colasanti M et al (2020) Association of sarcopenia and body composition with short-term outcomes after liver resection for malignant tumors. JAMA Surg 155:e203336. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3336

Peng PD, van Vledder MG, Tsai S et al (2011) Sarcopenia negatively impacts short-term outcomes in patients undergoing hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastasis. HPB 13:439–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00301.x

Valero V, Amini N, Spolverato G et al (2015) Sarcopenia adversely impacts postoperative complications following resection or transplantation in patients with primary liver tumors. J Gastrointest Surg 19:272–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2680-4

Deng H-Y, Hou L, Zha P et al (2019) Sarcopenia is an independent unfavorable prognostic factor of non-small cell lung cancer after surgical resection: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 45:728–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.09.026

Sjøblom B, Grønberg BH, Benth JŠ et al (2015) Low muscle mass is associated with chemotherapy-induced haematological toxicity in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 90:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.07.001

Mourtzakis M, Prado CMM, Lieffers JR et al (2008) A practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33:997–1006. https://doi.org/10.1139/H08-075

Looijaard SMLM, Lintel Hekkert ML, Wüst RCI et al (2021) Pathophysiological mechanisms explaining poor clinical outcome of older cancer patients with low skeletal muscle mass. Acta Physiol 231:13516. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13516

Levolger S, van Vugt JLA, de Bruin RWF, IJzermans JNM, (2015) Systematic review of sarcopenia in patients operated on for gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies. Br J Surg 102:1448–1458. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9893

Trejo-Avila M, Bozada-Gutiérrez K, Valenzuela-Salazar C et al (2021) Sarcopenia predicts worse postoperative outcomes and decreased survival rates in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 36:1077–1096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-021-03839-4

Xu L, Jing Y, Zhao C et al (2020) Preoperative computed tomography-assessed skeletal muscle index is a novel prognostic factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma following hepatectomy: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol 11:1040–1053. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-122

Simonsen C, de Heer P, Bjerre ED et al (2018) Sarcopenia and postoperative complication risk in gastrointestinal surgical oncology. Ann Surg 268:58–69. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002679

Lodewick TM, Van Nijnatten TJA, Van Dam RM et al (2015) Are sarcopenia, obesity and sarcopenic obesity predictive of outcome in patients with colorectal liver metastases? HPB (Oxford) 17:438–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/HPB.12373

Amini N, Spolverato G, Gupta R et al (2015) Impact total psoas volume on short- and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a new tool to assess sarcopenia. J Gastrointest Surg 19:1593–1602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-2835-y

Huang D-D, Wang S-L, Zhuang C-L et al (2015) Sarcopenia, as defined by low muscle mass, strength and physical performance, predicts complications after surgery for colorectal cancer. Color Dis 17:O256–O264. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13067

Levolger S, van Vledder MG, Muslem R et al (2015) Sarcopenia impairs survival in patients with potentially curable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 112:208–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23976

Dello SAWG, Lodewick TM, van Dam RM et al (2013) Sarcopenia negatively affects preoperative total functional liver volume in patients undergoing liver resection. HPB 15:165–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00517.x

Marasco G, Serenari M, Renzulli M et al (2020) Clinical impact of sarcopenia assessment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing treatments. J Gastroenterol 55:927–943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-020-01711-w

Cao Q, Xiong Y, Zhong Z, Ye Q (2019) Computed tomography-assessed sarcopenia indexes predict major complications following surgery for hepatopancreatobiliary malignancy: a meta-analysis. Ann Nutr Metab 74:24–34. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494887

Zhang G, Meng S, Li R et al (2017) Clinical significance of sarcopenia in the treatment of patients with primary hepatic malignancies, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 8:102474. https://doi.org/10.18632/ONCOTARGET.19687

Martin D, Maeder Y, Kobayashi K et al (2022) Association between CT-based preoperative sarcopenia and outcomes in patients that underwent liver resections. Cancers (Basel) 14:261. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14010261

Zhou G, Bao H, Zeng Q et al (2015) Sarcopenia as a prognostic factor in hepatolithiasis-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients following hepatectomy: a retrospective study. Int J Clin Exp Med 8:18245

Kroh A, Uschner D, Lodewick T et al (2019) Impact of body composition on survival and morbidity after liver resection in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 18:28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HBPD.2018.07.008

Runkel M, Diallo TD, Lang SA et al (2021) The role of visceral obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity on surgical outcomes after liver resections for colorectal metastases. World J Surg 45:2218–2226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06073-9

Seror M, Sartoris R, Hobeika C et al (2021) Computed tomography-derived liver surface nodularity and sarcopenia as prognostic factors in patients with resectable metabolic syndrome-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 28:405–416. https://doi.org/10.1245/S10434-020-09143-9/FIGURES/2

Dunne RF, Loh KP, Williams GR et al (2019) Cachexia and sarcopenia in older adults with cancer: a comprehensive review. Cancers (Basel) 11:1861. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11121861

Shachar SS, Williams GR, Muss HB, Nishijima TF (2016) Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur J Cancer 57:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.030

Dodson RM, Firoozmand A, Hyder O et al (2013) Impact of sarcopenia on outcomes following intra-arterial therapy of hepatic malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg 17:2123–2132. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11605-013-2348-5/TABLES/4

Pratesi A (2013) Skeletal muscle: an endocrine organ. Clin CASES Miner BONE Metab 10:11–14. https://doi.org/10.11138/ccmbm/2013.10.1.011

Ruiz-Casado A, Martín-Ruiz A, Pérez LM et al (2017) Exercise and the hallmarks of cancer. Trends in cancer 3:423–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRECAN.2017.04.007

Aoi W, Naito Y, Takagi T et al (2013) A novel myokine, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), suppresses colon tumorigenesis via regular exercise. Gut 62:882–889. https://doi.org/10.1136/GUTJNL-2011-300776

Nascimento CM, Ingles M, Salvador-Pascual A et al (2019) Sarcopenia, frailty and their prevention by exercise. Free Radic Biol Med 132:42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FREERADBIOMED.2018.08.035

Stene GB, Helbostad JL, Balstad TR et al (2013) Effect of physical exercise on muscle mass and strength in cancer patients during treatment–a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 88:573–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRITREVONC.2013.07.001

Yamamoto K, Nagatsuma Y, Fukuda Y et al (2017) Effectiveness of a preoperative exercise and nutritional support program for elderly sarcopenic patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 20:913–918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0683-4

Dallmann R, Weyermann P, Anklin C et al (2011) The orally active melanocortin-4 receptor antagonist BL-6020/979: a promising candidate for the treatment of cancer cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2:163–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13539-011-0039-1

Kabarriti R, Bontempo A, Romano M et al (2018) The impact of dietary regimen compliance on outcomes for HNSCC patients treated with radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer 26:3307–3313. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-018-4198-X

Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Ebata T (2021) Importance of “muscle” and “intestine” training before major HPB surgery: a review. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 28:545–555. https://doi.org/10.1002/JHBP.835

Kelly KN, Iannuzzi JC, Rickles AS et al (2014) Risk factors associated with 30-day postoperative readmissions in major gastrointestinal resections. J Gastrointest Surg 18:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11605-013-2354-7/TABLES/6

Simonsen C, Kristensen TS, Sundberg A et al (2021) Assessment of sarcopenia in patients with upper gastrointestinal tumors: prevalence and agreement between computed tomography and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Clin Nutr 40:2809–2816. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLNU.2021.03.022

Okumura S, Kaido T, Hamaguchi Y et al (2017) Impact of skeletal muscle mass, muscle quality, and visceral adiposity on outcomes following resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 24:1037–1045. https://doi.org/10.1245/S10434-016-5668-3/TABLES/2

van Vledder MG, Levolger S, Ayez N et al (2012) Body composition and outcome in patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases19. Br J Surg 99:550–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7823

Bajrić T, Kornprat P, Faschinger F et al (2022) Sarcopenia and primary tumor location influence patients outcome after liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol 48:615–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJSO.2021.09.010

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ et al (2008) Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 9:629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70153-0

Eriksson S, Nilsson JH, Strandberg Holka P et al (2017) The impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on skeletal muscle depletion and preoperative sarcopenia in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases. HPB 19:331–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HPB.2016.11.009

Kobayashi A, Kaido T, Hamaguchi Y et al (2018) Impact of visceral adiposity as well as sarcopenic factors on outcomes in patients undergoing liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg 42:1180–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00268-017-4255-5/TABLES/4

Hamaguchi Y, Kaido T, Okumura S et al (2017) Impact of skeletal muscle mass index, intramuscular adipose tissue content, and visceral to subcutaneous adipose tissue area ratio on early mortality of living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 101:565–574. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001587

Martin L, Birdsell L, MacDonald N et al (2013) Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol 31:1539–1547. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722

Meister FA, Lurje G, Verhoeven S et al (2022) The role of sarcopenia and myosteatosis in short- and long-term outcomes following curative-intent surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in a European cohort. Cancers (Basel) 14:720. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030720

Eslamparast T, Montano-Loza AJ, Raman M, Tandon P (2018) Sarcopenic obesity in cirrhosis—the confluence of 2 prognostic titans. Liver Int 38:1706–1717. https://doi.org/10.1111/LIV.13876

Takagi K, Yagi T, Yoshida R et al (2016) Sarcopenia and American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status in the Assessment of Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Undergoing Hepatectomy. Acta Med Okayama 70:363–370. https://doi.org/10.18926/AMO/54594

Voron T, Tselikas L, Pietrasz D et al (2015) Sarcopenia impacts on short- and long-term results of hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 261:1173–1183. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000743

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MT and AS. Methodology: AS, MT and AW. Acquisition of data and analysis: MT, AS, AW, and AS. Writing — original draft preparation: MT and AS. Writing — critical review and editing: JO, RD, RC, AP, and MP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thormann, M., Omari, J., Pech, M. et al. Low skeletal muscle mass and post-operative complications after surgery for liver malignancies: a meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407, 1369–1379 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02541-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-022-02541-5