Abstract

Background

Selection criteria and prognostic factors for patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) undergoing cytoreductive surgery (CRS) plus hyperthermic intra-operative peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) have not been well defined, and the literature data are not homogeneous. The aim of this study was to compare prognostic factors influencing overall (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in a population of patients affected by AGC with surgery alone and surgery plus HIPEC, both with curative (PCI, peritoneal carcinomatosis index > 1) and prophylactic (PCI = 0) intent.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected database was conducted in patients affected by AGC from January 2006 to December 2015. Uni- and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors were performed.

Results

A total of 85 patients with AGC were analyzed. A 5-year OS for surgery alone, CRS plus curative HIPEC, and surgery plus prophylactic HIPEC groups was 9%, 27% and 33%, respectively. Statistical significance was reached comparing both prophylactic HIPEC vs surgery alone group (p = 0.05), curative HIPEC vs surgery alone group (p = 0.03), and curative vs prophylactic HIPEC (p = 0.04). A 5-year DFS for surgery alone, CRS + curative HIPEC, and surgery + prophylactic HIPEC groups was 9%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. Statistical significance was reached comparing both prophylactic HIPEC vs surgery alone group (p < 0.0001), curative HIPEC vs surgery alone group (p = 0.008), and curative vs prophylactic HIPEC (p = 0.05).

Conclusions

Patients with AGC undergoing surgery plus HIPEC had a better OS and DFS with respect to patients treated with surgery alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the sixth most prevalent malignant tumor worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related death. The International Agency for Research on Cancer estimated that there were about one million new cases of gastric cancer and 782,685 deaths from gastric cancer in 2018 [1]. Many patients in the western world with AGC die from metastases [2].

The peritoneal cavity is also a frequent site for metastatic disease after resection, particularly in patients with serosa-infiltrating tumors [3, 4]. Patients with AGC and peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) have a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 3.1 months without treatment [5]. Systemic chemotherapy extended the median survival time to 11 months in patients with AGC compared with best supportive care alone [6].

Extended resection involving gastrectomy and peritonectomy combined with administration of HIPEC may improve survival in patients with PC [7,8,9]. HIPEC possesses a theoretical advantage over systemic treatment delivering high drug concentrations directly to the peritoneal cavity, resulting in a reduced systemic toxicity [10,11,12]. In addition, high drug concentrations are achieved in the portal vein [13, 14].

Extended survival with HIPEC in AGC has been demonstrated, but the lack of standardized protocols has led to difficulties comparing and interpreting results [15]. A meta-analysis demonstrated improved overall survival with HIPEC with or without early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy [16].

Perhaps the most appropriate use of HIPEC in AGC would be prophylactic, suggesting an adjunct to curative surgical resection in patients with a high risk of peritoneal recurrence. Not surprisingly, the majority of data related to HIPEC in AGC is prophylactic against peritoneal recurrences. The theoretical rationale and synergistic effect is that large diluent volumes in HIPEC wash out most of the intraperitoneal free cancer cells and chemotherapy destroys remaining cancer cells [17].

With the aim of contributing to this issue, we have conducted a comparative observational analysis between patients undergoing CRS alone and those who received gastrectomy plus HIPEC both with curative (PCI > 1) and prophylactic (PCI = 0) intent.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data was conducted regarding patients with AGC observed and treated at the Digestive Surgery Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “A. Gemelli” IRCCS, from January 2006 to December 2015.

We preliminarily obtained Institutional Review Board approval to use patient data.

Patients analyzed were divided into the following 3 groups:

-

Surgery plus HIPEC with curative intent: AGC patients with apparent peritoneal dissemination who underwent cytoreductive surgery, including gastrectomy and partial peritonectomy of peritoneal sections affected by implants, followed by HIPEC

-

Surgery plus HIPEC with prophylactic intent: AGC patients with serosa invasion and consequent high risk of intraperitoneal progression, who underwent gastrectomy followed by HIPEC

-

Surgery alone: AGC patients who underwent only gastrectomy due to the presence of exclusion criteria for HIPEC

The same team of oncologists performed all surgeries, and all patients had to provide a written informed consent before the intervention.

Patients were divided according to the type of surgical procedure performed.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All patients were submitted to a complete clinical evaluation, including laboratory tests, with complete blood cell count and serum chemistry.

In order to exclude extra-abdominal disease and to assess the possibility of optimal cytoreduction, all patients underwent to a CT scan or FDG-PET/CT scan. A preoperative laparoscopy was selectively performed for the purpose of selecting patients for neoadjuvant therapy.

Patients with histologically documented AGC, with a preoperative stage II to IV, with peritoneal carcinomatosis (stage IV) or at high risk to develop it due to serosal involvement, were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18–80 years, normal cardiac, respiratory, liver and renal functions, and no hematological alterations.

Exclusion criteria for HIPEC were uncontrolled severe infection and/or medical problems unrelated to malignancy which would limit full compliance with the protocol or expose the patient to extreme risk of life.

All patients in surgery alone group were excluded from HIPEC due to the presence of an exclusion criteria.

All patients included were analyzed without defining any cut-off value for PCI and CC score.

We recorded hospital morbidity and mortality, type of treatment, histologic type according to Lauren [18], and demographic characteristics, tumor size, and tumor location. The disease was staged according to the 8th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the International Union Against Cancer Staging System (UICC) [19, 20].

Surgical rules

Based on categories established by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association [21], the regional extent of nodal involvement after radical procedures was also recorded.

At the end of the operation, the surgeon resected all lymph nodes from the surgical specimen and identified their distribution and tumor location according to the classification by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association [21].

The PCI score was calculated at laparotomy [22]. The CC score was calculated for all patients in the three groups. CC-0 reflected no remaining visible disease. CC-1, 2, and 3 implied remaining disease less than 2.5 mm, 2.5 to 2.5 cm, and greater than 2.5 cm [22].

After total gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection, esophagojejunostomy (using a circular stapler, diameter 25 mm) was used routinely for Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

In case of subtotal gastrectomy, intestinal continuity was restored by means of Billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, at discretion of the surgeon.

In case of carcinomatosis, CRS was performed removing all peritoneum and visceral organs involved.

Extensive surgery (associated resections) because of suspicion of direct tumor invasion or carcinomatosis was defined as combined resection of adjacent organs (spleen, left pancreas, liver, colon, adrenal gland, diaphragm, abdominal wall, and small intestine).

HIPEC

HIPEC was carried out according to the coliseum technique [22]. Two inflow and two outflow 29 French catheters were placed in the upper and lower abdominal quadrants, respectively. The HIPEC procedure was administered for 90 min with an inflow temperature of 41–42 °C and an outflow temperature of 39–40 °C, using mitomycin C (MMC) at a dose of 15 mg/m2 and cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m2. As perfusate volume, a 2 L/m2 0.9% NaCl solution was used. At the end of the procedure, an abdominal washout was performed with 3 L of crystalloid solution. After 90 min of perfusion, the abdomen was cautiously re-explored to control the hemostasis.

The temperature was monitored using digital probes placed in abdominal cavity at circuit level.

Pathological data

Based on definitive pathologic findings, the potentially curative operations were classified as radical (R0-microscopic tumor free) or as R1-microscopic residual disease—according to the presence or absence of residual tumor. Palliative resection was classified based on R2 macroscopic

disease left behind. Frozen sections were not routinely used in the evaluation of margins, but only in the suspicion of a possible tumor infiltration.

Postoperative course

The patients were monitored for 30-day postoperative complications and mortality.

Early postoperative complications were considered occurring within 30 days from surgery and with a severity grade 2 or more according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [23]. All postoperative complications were registered in the database during hospitalization or at the first follow-up, by telephone contact, within 30 days from surgery.

Postoperative mortality was defined as death within 30 days from surgery.

Perioperative chemotherapy was administered, in the majority of cases, according to the MRC Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy (MAGIC) protocol [24].

The oncologists decided about adjuvant chemotherapy administration, as previously reported [25], resulting in heterogeneity regarding chemotherapy, treatment protocols, and a number of cycles performed.

All patients included in the study were regularly followed up with a standardized protocol [26].

Statistical analyses

All clinical and pathological data were prospectively stored in a GC database and evaluated for this study. All variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (±), median, and interquartile range (IQR) when appropriate. The statistical significance of the difference between mean values was evaluated using the Student’s t test. All tests were two tailed. Categorical variables were assessed by the Pearson’s Chi-square test. Multivariable analysis was undertaken using the Cox proportional hazards model. The survival adjusted for censoring was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the medians were compared using the log-rank test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All data were analyzed by SPSS version 25® (IBM, IL, USA).

Results

During the study period, a total of 427 patients with GC underwent surgery with curative intent at the Digestive Surgery Unit of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “A. Gemelli” IRCCS of Rome.

Among them, 85 patients with advanced GC were retrospectively analyzed for this observational study. More specifically, forty-six patients (F/M ratio 25/21; mean age 55 years, range 28–76) underwent surgery plus HIPEC. In 50% (23/46) of cases, indication for HIPEC was a T3/T4 gastric cancer without peritoneal carcinomatosis (PCI = 0). Thirty-nine patients received CRS alone.

Clinico-demographic characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1.

The median follow-up (IQR) was 68 months.

Excluding 4 patients lost during the study period and 3 patients who died during the postoperative hospital stay (1 in the curative HIPEC group and 2 in the only surgery group), follow-up was completed in 78 cases (91.7%). At the last evaluation, 54 (63.5%) patients had died.

Positive cytology was present only in 6 patients (26%) who underwent prophylactic HIPEC.

Thirty-eight patients (44.7%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a pathological response in 19 cases (50%).

The majority of patients was preoperatively classified as ASA 2 (50 patients, 59%).

Seventy-seven patients (90.6%) had ≥ 15 lymph nodes retrieved, and 75 (88.2%) were N+.

The mean duration of surgical procedures was 338 (± 92.7) minutes, and the mean length of postoperative hospital stay was 13.4 (± 9.3) days.

Forty-one patients (48.2%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Clinico-demographic characteristics of the three groups are shown in Table 2.

A significant difference among the three groups was noticed regarding the distribution of ASA score, tumor location and tumor stage, PCI range, CC score, and R status.

Intra-operative and short-term outcomes for the three groups are shown in Table 3.

Among the three groups, a significant difference was detected as far as associated resections and operation time were concerned (p = 0.008 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

No differences between the three groups neither in terms of postoperative complications (p = 0.8) nor in terms of postoperative mortality (p = 0.55) rates were observed.

In the groups of patients who received HIPEC, only one case of postoperative intestinal ischemia, and one episode of acute renal failure was observed, probably HIPEC-related.

Prognostic factors affecting OS and DFS according to univariate analysis are shown in Table 4.

Tumor location, stage IIIB, PCI ≥ 6, CC score > 0, N+, type of resection, HIPEC, and the type of HIPEC (prophylactic vs curative) significantly affected both OS and DFS. R status significantly affected only DFS (p < 0.0001).

Table 5 shows multivariate analysis of factors associated with OS and DFS.

At the multivariate analysis for OS, PCI ≥ 6, CC > 0, N+ status, and the absence of HIPEC were statistically significant.

On the other hand, at the multivariate analysis, DFS was significantly influenced by PCI ≥ 6, CC > 0, R status, and the absence of HIPEC.

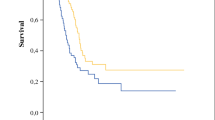

A 5-year OS for surgery alone, CRS + curative HIPEC, and surgery + prophylactic HIPEC groups was 9%, 27%, and 33%, respectively (Fig. 1). Statistical significance was reached comparing both prophylactic HIPEC vs surgery alone group (p = 0.05) and curative HIPEC vs surgery alone group (p = 0.03).

Forty-six patients (54.1%) experienced a cancer recurrence, 23 in surgery alone group, 13 in curative HIPEC group, and 10 in prophylactic HIPEC group. In all cases, it was a peritoneal dissemination. A 5-year DFS for surgery alone, CRS plus curative HIPEC, and surgery plus prophylactic HIPEC groups was 9%, 20%, and 30%, respectively (Fig. 2) (p = ns). Statistical significance was reached comparing prophylactic HIPEC vs CRS alone group (p = 0.008).

The intraperitoneal recurrence rates in patients in surgery plus HIPEC with curative intent group, surgery in surgery plus HIPEC with prophylactic intent group, and in surgery alone group were 28.2%, 21.7%, and 65.4%, respectively (p = 0.007).

Discussion

Despite the high level of evidence, data supporting the use of CRS + HIPEC for treating AGC, with or without PC, is still not accepted as a standard treatment, likely because AGC is still associated with a poor prognosis, even without peritoneal disease [27, 28].

Intraperitoneal administration of chemotherapy results in a regional dose intensification, i.e., a high

intraperitoneal concentration of the drug with a low plasma concentration [29].

Scaringi et al. [30] reported that complete CRS plus HIPEC increased advanced AGC patients’ survival rates, especially in those without macroscopic peritoneal residuals.

However, wide application of CRS plus HIPEC is hampered by the adverse effects of chemotherapy.

To the best of our knowledge, our study represents the first experience comparing CRS alone, CRS plus HIPEC with curative intent, and CRS plus HIPEC with prophylactic intent in patients with AGC.

In our paper, we demonstrated that tumor location, advanced T stage, PCI > 6, CC score > 0, N+, type of resection, and the use of HIPEC significantly affected both OS and DFS. R status significantly affected only DFS (p < 0.0001).The earliest report of the use of HIPEC as an adjuvant treatment to prevent peritoneal recurrence was by Koga et al. [31]. They reported two studies, the first a historical study comparing 38 GC patients with serosal invasion who underwent curative surgery followed by HIPEC using MMC with a control group of 55 patients who underwent curative surgery without HIPEC. They found that the HIPEC group had a significantly improved 3-year survival (74% vs 53%, p < 0.04) with fewer peritoneal recurrences (36% vs 50%) respectively. Subsequently, they performed a randomized study in which patients were randomized to undergo curative surgery with HIPEC or only surgery. In this study also, they found that patients who received HIPEC had a trend towards a better 30-month survival compared to the control group (83% vs 67%) although this was not statistically significant.

Fujimoto et al. [32] reported a prospective study of 59 patients, 32 of whom had advanced AGC without PC who underwent curative surgery. The 2-year survival of the 10 patients who received HIPEC was significantly higher than that of the 20 patients who did not (56.5% vs 12.9%, p = 0.01). While no patient in the former group developed peritoneal recurrence, 8 patients in the latter group died due to peritoneal recurrence.

There have been various randomized controlled trials comparing HIPEC vs no HIPEC in patients with locally AGC who underwent a potentially curative resection [17]. Although there is some heterogeneity in these trials with respect to the drugs used, their dosage, duration of HIPEC, temperature achieved, etc., these trials provide level 1 evidence of the ability of adjuvant HIPEC to reduce peritoneal recurrence and improve survival. Not many studies have evaluated the effects of prophylactic HIPEC in patients with Cy+/P0 GC [33].

In a meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, Sun et al. [34] demonstrated a significant advantage in survival with the use of HIPEC, regardless of the chemotherapy used (MMC or 5-FU) and also regardless of whether adjuvant systemic chemotherapy was used or not.

In a pooled analysis of 16 RCTs, Mi et al. [28] reported a significant improvement in the 1, 2, 3, 5, and 9-year survival and a reduction in the peritoneal recurrence rates at 2, 3, and 5 years in patients who received HIPEC compared to those who did not.

These results indicate that intraperitoneal chemotherapy is best delivered at the time of surgery to treat the microscopic dissemination that occurs before or during surgery [28] and that hyperthermia has a synergistic effect with intraperitoneal chemotherapy perfusion.

In summary, adjuvant HIPEC used as prophylaxis against peritoneal recurrence in patients with high-risk GC (serosal invasion or nodal metastasis) is safe, significantly improves the survival, and reduces the risk of peritoneal recurrence. However, most of these RCTs have been conducted in Asian countries, and the data from the western world is scarce.

The GASTRICHIP study is a phase III randomized European multicenter study evaluating the role

of HIPEC with oxaliplatin in patients with GC who have either serosal infiltration and/or lymph nodal involvement and/or positive peritoneal cytology treated by a curative gastrectomy [35]. The most recent meta-analysis by Desiderio et al. [36] demonstrated a survival advantage of the use of HIPEC as a prophylactic strategy and suggests that patients whose disease burden is limited to positive cytology and limited nodal involvement may benefit the most from HIPEC. Moreover, for patients with extensive carcinomatosis, the completeness of cytoreductive surgery is a critical prognostic factor for survival [37]. Future RCTs should better define patient selection criteria.

The first report from the western world on role of extensive surgery plus HIPEC came from Sayag-Beaujard et al. [38]. The authors reported a phase II study of 42 patients with AGC with peritoneal disease who underwent HIPEC with MMC. The overall median survival was 10.3 months, and the 5-year survival was 8%.

In a large series of 107 patients reported in 2005, Yonemura et al. [39] compared 65 patients who underwent conventional surgery followed by HIPEC for PC from GC with 42 patients who had a peritonectomy as described by Sugarbaker [7] followed by HIPEC. The median survival for all 107 patients was 11.5 months, and the 5-year survival was 6.7%, but the 5-year survival for the patients who underwent peritonectomy and HIPEC was 27%. Performing a peritonectomy enabled a higher rate of complete cytoreduction and, subsequently, a better survival.

Compared to the most recent literature experiences, our study presented better 5-year-OS rates both for curative and prophylactic HIPEC (27% and 33%, respectively) comparing to CRS alone group (9%). Also, 5-year-DFS rates resulted significantly higher in patients undergoing HIPEC with respect to those who did not (20% and 30% vs 9%, respectively).

The French CYTO-CHIP study by Bonnot et al. [40] is the most recent multicentric study from 19 centers of the FREGAT and the BIG-RENAPE networks that focused especially on the effect of HIPEC after complete CRS using a propensity score analysis. With 277 patients, it represents actually the largest study concerning CRS-HIPEC and gastric cancer. It showed a strong positive effect of HIPEC after CRS versus CRS alone without additional morbidity. Survival rates were similar to those reported in our study. Despite that our study represents the first experience comparing HIPEC with curative and prophylactic intent respect to surgery alone, some major limitations should be evidenced.

First, all data were retrospectively collected, and hence, potential biases could derive from the study design. Second, it reports a single-center non-randomized experience with small sample size groups.

Thirdly, patients with uncontrolled severe infection and/or medical problems unrelated to malignancy were excluded from HIPEC. The selection of treatment results in uncontrollable biases.

Even so, we can conclude that in our experience, in selected patients with AGC, surgery plus HIPEC had a better OS and DFS with respect to patients treated with surgery alone.

Conclusions

In conclusion, according to the results of the present study, patients with AGC undergoing surgery plus HIPEC, both with prophylactic and curative intent, had a better OS and DFS with respect to patients treated with surgery alone. Nevertheless, the role of CRS with HIPEC in AGC with macroscopic PC is still evolving and needs to be addressed in large multi-institutional randomized trials.

Moreover, some issues in the use of HIPEC as an adjuvant treatment in GC—choice of drug, dosage, duration of treatment, for which there is no consensus—are far to be resolved.

Widespread acceptance and adoption of prophylactic and curative HIPEC in AGC require a satisfactory answer to these issues.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424

Sugarbaker PH, Yonemura Y (2000) Clinical pathway for the management of resectable gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding: best palliation with a ray of hope for cure. Oncology 58:96–107

Chu DZ, Lang NP, Thompson C, Osteen PK, Westbrook KC (1989) Peritoneal carcinomatosis in nongynecological malignancy. A prospective study of prognostic factors. Cancer 63:364–367

Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS (2000) Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg 87:236–242

Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, Fontaumard E, Brachet A, Caillot JL, Faure JL, Porcheron J, Peix JL, François Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN (2000) Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE I multicentric prospective study. Cancer 88:358–363

Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J et al (2010) Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 17(3):CD004064. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3

Sugarbaker PH (1995) Peritonectomy procedures. Ann Surg 221:29–42

Gilly FN, Carry PY, Sayag AC, Brachet A, Panteix G, Salle B, Bienvenu J, Burgard G, Guibert B, Banssillon V (1994) Regional chemotherapy (with mitomycin C) and intra-operative hyperthermia for digestive cancers with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Hepatogastroenterology 41:124–129

Fujimoto S, Takahaschi M, Mutou T, Kobayashi K, Toyosawa T, Isawa E et al (1997) Improved mortality rate of gastric carcinoma patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion combined with surgery. Cancer 79:884–891

Yonemura Y, Ninomiya I, Kaji M, Sugiyama K, Fujimura T, Sawa T et al (1995) Prophylaxis with intraoperative chemohyperthermia against peritoneal recurrence of serosal invasion-positive gastric cancer. World J Surg 19:450–455

Dedrick R (1985) Theoretical and experimental bases of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Semin Oncol 12:1–6

Shimada T, Nomura M, Yokogawa K, Endo Y, Sasaki T, Miyamoto K, Yonemura Y (2005) Pharmacokinetic advantage of intraperitoneal injection of docetaxel in the treatment for peritoneal dissemination of cancer in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol 57:177–181

Speyer JL, Sugarbaker PH, Collins JM, Dedrick RL, Klecker RW Jr, Myers CE (1981) Portal levels and hepatic clearance of 5-fluorouracil after intraperitoneal administration in humans. Cancer Res 41:1916–1922

Laundry J, Tepper JE, Wood WC, Moulton EO, Koerner F, Sullinger J (1990) Patterns of failure following curative resection of gastric carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 19:1357–1362

Glockzin G, Schlitt HJ, Piso P (2009) Peritoneal carcinomatosis: patients selection, perioperative complications and quality of life related to cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol 7:5

Yan TD, Black D, Sugarbaker PH, Zhu J, Yonemura Y, Petrou G, Morris DL (2007) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials on adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 14:2702–2713

Seshadri RA, Glehen O (2016) Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 22:1114–1130

Lauren P (1965) The two histological main types of gastric cancer carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 64:31–49

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP (2017) The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. Ca - Cancer J Clin. 67:93–99

O'Sullivan B, Brierley J, Byrd D, Bosman F, Kehoe S, Kossary C, Piñeros M, van Eycken E, Weir HK, Gospodarowicz M (2017) The TNM classification of malignant tumours-towards common understanding and reasonable expectations. Lancet Oncol 18:849–851

(2011) Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 14(2):101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5

Sugarbaker PH (1999) Management of peritoneal-surface malignancy: the surgeon’s role. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 384:576–587

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 240:205–213

Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M et al (2006) Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 355:11–20

Rosa F, Alfieri S, Tortorelli AP, Fiorillo C, Costamagna G, Doglietto GB (2014) Trends in clinical features, postoperative outcomes, and long-term survival for gastric cancer: a Western experience with 1,278 patients over 30 years. World J Surg Oncol 16(12):217

Baiocchi GL, Marrelli D, Verlato G, Morgagni P, Giacopuzzi S, Coniglio A, Marchet A, Rosa F, Capponi MG, di Leo A, Saragoni L, Ansaloni L, Pacelli F, Nitti D, D'Ugo D, Roviello F, Tiberio GA, Giulini SM, de Manzoni G (2014) Follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer: an appraisal of the Italian research group for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 21:2005–2011

Imano M, Yasuda A, Itoh T, Satou T, Peng YF, Kato H, Shinkai M, Tsubaki M, Chiba Y, Yasuda T, Imamoto H, Nishida S, Takeyama Y, Okuno K, Furukawa H, Shiozaki H (2012) Phase II study of single intraperitoneal chemotherapy followed by systemic chemotherapy for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. J Gastrointest Surg 16:2190–2196

Mi DH, Li Z, Yang KH, Cao N, Lethaby A, Tian JH, Santesso N, Ma B, Chen YL, Liu YL (2013) Surgery combined with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IHIC) for gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Hyperthermia 29:156–167

González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G (2010) Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2:68–75

Scaringi S, Kianmanesh R, Sabate JM, Facchiano E, Jouet P, Coffin B, Parmentier G, Hay JM, Flamant Y, Msika S (2008) Advanced gastric cancer with or without peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a single western center experience. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 34:1246–1252

Koga S, Hamazoe R, Maeta M, Shimizu N, Murakami A, Wakatsuki T (1988) Prophylactic therapy for peritoneal recurrence of gastric cancer by continuous hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion with mitomycin C. Cancer 61:232–237

Fujimoto S, Shrestha RD, Kokubun M, Kobayashi K, Kiuchi S, Konno C et al (1990) Positive results of combined therapy of surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion for far-advanced gastric cancer. Ann Surg 212:592–596

Sugarbaker PH, Yu W, Yonemura Y (2003) Gastrectomy, peritonectomy, and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: the evolution of treatment strategies for advanced gastric cancer. Semin Surg Oncol 21:233–248

Sun J, Song Y, Wang Z, Gao P, Chen X, Xu Y, Liang J, Xu H (2012) Benefits of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for patients with serosal invasion in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 12:526

Glehen O, Passot G, Villeneuve L, Vaudoyer D, Bin-Dorel S, Boschetti G, Piaton E, Garofalo A (2014) GASTRICHIP: D2 resection and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in locally advanced gastric carcinoma: a randomized and multicenter phase III study. BMC Cancer 14:183

Desiderio J, Chao J, Melstrom L, Warner S, Tozzi F, Fong Y, Parisi A, Woo Y (2017) The 30-year experience-A meta-analysis of randomised and high-quality non-randomised studies of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 79:1–14

Yang XJ, Huang CQ, Suo T, Mei LJ, Yang GL, Cheng FL, Zhou YF, Xiong B, Yonemura Y, Li Y (2011) Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol 18(6):1575–1581

Sayag-Beaujard AC, Francois Y, Glehen O, Sadeghi-Looyeh B, Bienvenu J, Panteix G, Garbit F, Grandclément E, Vignal J, Gilly FN (1999) Intraperitoneal chemo-hyperthermia with mitomycin C for gastric cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Anticancer Res 19:1375–1382

Yonemura Y, Kawamura T, Bandou E, Takahashi S, Sawa T, Matsuki N (2005) Treatment of peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer by peritonectomy and chemohyperthermic peritoneal perfusion. Br J Surg 92:370–375

Bonnot PE, Piessen G, Kepenekian V, Decullier E, Pocard M, Meunier B, Bereder JM, Abboud K, Marchal F, Quenet F, Goere D, Msika S, Arvieux C, Pirro N, Wernert R, Rat P, Gagnière J, Lefevre JH, Courvoisier T, Kianmanesh R, Vaudoyer D, Rivoire M, Meeus P, Passot G, Glehen O, on behalf of the FREGAT and BIG-RENAPE Networks (2019 Aug 10) Cytoreductive surgery with or without hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastases (CYTO-CHIP study): a propensity score analysis. J Clin Oncol. 37(23):2028–2040

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Rosa, Ricci, Quero, Longo, Alfieri

Acquisition of data: Covino, Rosa, Galiandro, Longo

Analysis and interpretation of data: Rosa, Ricci, Galiandro, Quero, Tortorelli, Alfieri

Drafting of manuscript: Rosa, Galiandro, Quero

Critical revision: Tortorelli, Alfieri

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosa, F., Galiandro, F., Ricci, R. et al. Survival advantage of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for advanced gastric cancer: experience from a Western tertiary referral center. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406, 1847–1857 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02102-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02102-2