Abstract

Introduction

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) has a heterogenous clinical and radiological presentation. We investigated whether RCVS complications vary according to age.

Patients and methods

In a pooled French cohort of 345 patients with RCVS, we assessed (1) rates of clinical and radiological complications, and (2) the functional outcome at 3 months according to age as a continuous variable, and in young patients aged ≤ 49 years versus those aged ≥ 50 years. The Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté and the local ethics committee approved this study (registration number: 202100733).

Results

The risk for any focal deficit and for any brain lesion were independently associated with increasing age (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.8; p = 0.014, and OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.1; p < 0.001, respectively). Subtypes of brain lesions independently associated with increasing age were subarachnoid haemorrhage (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.3–2.3; p < 0.001) and intracerebral haemorrhage (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.2; p = 0.023). Frequency of cervical artery dissections peaked at age 30–39, and young age was independently associated with cervical artery dissections (OR 13.6, 95% CI 2.4–76.6; p = 0.003). Age had no impact on the functional outcome, with a modified Rankin scale score of 0–1 in > 96% of patients.

Conclusion

Age seems to influence rates and types of complications of RCVS, with young age being associated with cervical artery dissections, and increasing age with haemorrhagic complications. If confirmed in larger prospective studies, recognition of age-specific patterns might help to guide clinical management and to identify complications in cases of RCVS and vice versa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is characterised by severe acute headache associated with segmental cerebral vasoconstriction resolving within 3 months [1, 2]. It predominantly affects women in their forties or fifties, with an age range of 4 months to 85 years [3,4,5]. Clinical spectrum of RCVS is heterogeneous ranging from pure cephalalgic forms to complications including focal deficits, seizures, ischaemic stroke, intracranial haemorrhage, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and cervical artery dissection [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Potential risk factors for such complications include female sex, postpartum, the absence of thunderclap headache at onset, and use of serotonergic antidepressants [8,9,10, 15].

Recently, analyses of the US Nationwide Readmission and Inpatient Databases identified advanced age as an independent risk factor for intracranial haemorrhage during RCVS, for higher length-of-stay in hospital, and for poor early outcome defined by discharge from hospital other-than-home [6, 16].

Studying risk factors for complications in RCVS is crucial in order to guide clinical management including the decision of ambulatory vs in-hospital care. We aimed to investigate whether clinico-radiological complications and prognosis of RCVS vary according to age.

Materials and methods

Study design and selection criteria

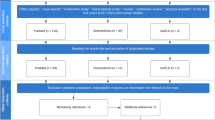

This is a pooled analysis of one prospective and two retrospective RCVS cohorts, which have been recruited at the French University Hospitals of Paris Lariboisière and Montpellier, as described before [9].

We included patients ≥ 15 years old with confirmed RCVS meeting the following criteria: (1) unusual, recent, severe headaches of sudden or progressive onset with or without focal neurologic deficit and/or seizures; (2) cerebral vasoconstriction with at least 2 narrowing on 2 different arteries, assessed by noninvasive brain vascular imaging investigations (CTA, contrast-enhanced MRA or Time-of-Flight (TOF)-MRA) or conventional cerebral angiography; and (3) disappearance of arterial abnormalities within the first 3 months.

At both hospitals, the performance of cerebral (CT, MRI) and cerebrovascular imaging investigations (CTA, MRA or conventional cerebral angiography) was left to the discretion of the physician in charge of the patient. All patients received vascular imaging at least once at onset to confirm vasoconstriction as defined above (criterion 2), and once at 3 months follow-up to confirm reversibility of vasoconstriction (criterion 3). Parenchymal imaging was repeated in case of clinical worsening. MR sequences at both hospitals included at least DWI, ADC, FLAIR and T2* or SWI, respectively.

At Lariboisière Hospital, all consecutive patients with proven RCVS were prospectively included from 2004 to 2011 (cohort A, n = 173). 70% of the patients were recruited from the emergency headache center [EHC], and 30% from the neurologic department including a stroke unit. Patient characteristics, treatment, and assessment of reversibility of vasoconstriction have been previously described [5]. All patients had a follow-up visit at 3 months in order to confirm clinical and radiological reversibility, and to assess the functional outcome. Further clinical follow-up visits were performed as previously described, with a mean follow-up period of 9.2 ± 3.3 years [17]. After the end of the prospective study at Lariboisière Hospital, patients were retrospectively included from 2012 to 2015, following the same inclusion criteria (cohort B, n = 132). 80% of the patients were recruited from the EHC, and 20% from the neurology department.

At the University Hospital of Montpellier, patients were retrospectively identified from the electronic database by using the International Classification of Diseases codes I67.84 and I67.9 from 2016 to 2019. For all identified cases (cohort C, n = 40), we analysed their medical records to ensure that they met the above-mentioned inclusion criteria. All identified patients had been admitted to the neurology department.

For both retrospective cohorts, clinical routine included a follow-up appointment at 3 months in order to clinically and radiologically confirm the diagnosis of RCVS according to the above-mentioned criteria, and to assess functional outcome.

Ethics approvals were obtained from the respective local institutional review boards. The database used in the study was approved by the Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté. The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Definitions of clinical characteristics

Migraine was diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders [18]. A thunderclap headache (TCH) was defined as a headache reaching a maximum intensity above 7/10, on an 11-point scale from 0 to 10 in < 1 min.

We assessed the delay between onset, precisely the first episode of headache or neurological deficit, and the first neurological examination. RCVS was qualified as secondary in the presence of a potential precipitating factor and as idiopathic when none could be identified.

We collected data on the occurrence of clinical symptoms (i.e., transient focal neurological deficit < 24 h, persistent focal neurological deficit ≥ 24 h, and seizure) and of radiological lesions (i.e., ischaemic stroke [IS], intracerebral haemorrhage [ICH], subarachnoid haemorrhage [SAH], subdural haematoma [SDH], posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome [PRES], and cervical artery dissections [CAD]), defined as complications of RCVS. Any clinical complication was defined as either any focal deficit and/or seizure. Any brain lesion was defined as ≥ 1 of the above-mentioned radiological lesions excluding CAD.

According to considerations for outcome definition in stroke trials [19], functional outcome was defined as good if the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 3-month clinical follow-up was 0–1, and as unfavourable if the mRS score was ≥ 2.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean (± standard deviation, SD) if normally distributed and as medians [interquartile range, IQR] if not normally distributed. Categorical variables were presented as numbers (%). Categorical variables were compared between two groups by Pearson´s chi-squared test or the Fisher exact test if Chi-square’s conditions were not met. For continuous variables, the Mann–Whitney-U-test was applied for comparison of non-normally distributed data. The mRS was dichotomised as 0–1 vs 2–6.

The univariable relationship between age and clinical characteristics was assessed in comparing younger vs older patients (≤ 49 vs > 50 years). We chose the cut-off of 50 years corresponding to the mean age of menopause, given the influence of female hormones in migraine and possibly in RCVS, and the high prevalence of migraine in patients with RCVS, decreasing after menopause [20,21,22].

The univariable relationship of age with clinical or radiological complications and with functional outcome was assessed graphically, using age groups (≤ 19, 20 to 29, 30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, ≥ 60 years), and statistically using the cutoff of 50 years.

To determine independent associations of age with the occurrence of clinical or radiological complications and an unfavourable functional outcome (mRS ≥ 2), we performed a stepwise forward logistic regression. Results are presented as multivariable odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals: OR [95% CI]. Depending on the shape of association with the outcome, age was used as a continuous variable with 10-year units, or as a categorical variable, with the a-priori cutoff of 50 years. To improve readability throughout the text, we label OR and p values ORC and pC when age was used as a continuous variable, and ORD and pD when age was used as a dichotomous variable, respectively.

Confounders known or supposed to be associated with age, with the occurrence of complications or unfavourable outcome in RCVS are: arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolaemia, current smoking, cannabis use, cocaine use, blood pressure surge, thunderclap headache at onset, sex, migraine, postpartum, anxiety or depression, and serotonergic antidepressant use. All confounders independently associated with outcomes are presented in the results. Since age was our primary exposure, we included age in every model irrespective of a statistically significant association with the outcome.

Patients with missing values for one of the covariates were excluded from multivariable analysis. Results were considered significant at a two-sided alpha-level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Clinical cohort characteristics (Table 1)

Comparison between the three pooled cohorts of RCVS patients has been presented and discussed before [9].

Mean age was 42 years (SD: 13, range 15–85). Five patients (1.4%) were younger than 18 years old, while patients ≥ 60 years represented 6.9% of the cohort. There was a female preponderance with two thirds of patients being women. A history of migraine was documented in 27% of patients.

Neurological examination in our institutions was performed with a median delay of 5 [IQR: 3–9] days after onset of symptoms. The most common triggers for headaches were sexual and physical activity. Two thirds of patients were hospitalised.

Occurrence of neurological complications

Information on the occurrence of clinical complications was available for all patients. MRI scans were performed in 97.4% (336/345) of patients. The remaining nine patients had purely cephalalgic RCVS with recurrent TCHs, normal CT imaging, and a self-limited clinical course in the absence of immunosuppressant treatment. Focal deficits and seizures were documented in 16% and 4% of patients, respectively. 27% of patients had at least one type of brain lesion. The most frequent radiological lesions were SAH, followed by CAD and ICH.

Clinical characteristics of patients aged ≤ 49 vs ≥ 50 years (Table 1)

Patients ≥ 50 years were significantly more often female (pD < 0.001), reported more often cardiovascular comorbidities, and more frequently a history of migraine (pD = 0.004). Exposure to cannabis and cocaine/crack was identified almost only in patients ≤ 49 years, while the use of serotonergic antidepressants was more common among patients ≥ 50 years (pD < 0.001, pD = 0.034; and pD = 0.003, respectively).

While the percentage of patients presenting with TCH at onset was equal between both groups, older patients reported less often sexual triggers for headache episodes, and more often other triggers including micturition and sudden movement (pD < 0.01, respectively). The frequency of physical effort, Valsalva maneuver, emotional stress and contact with water as headache triggers was similar between both groups. No difference was found concerning the delay from onset to the first neurological exam. Patients ≥ 50 years old were more frequently hospitalised (pD = 0.003).

Complications according to age

Figures 1 and 2 display the frequency of clinical and radiological complications according to age groups, indicating percentages of patients in each age group affected by each type of complication. eTable 1 supplements the absolute numbers of complications. Regarding clinical complications, seizures occurred only in patients aged ≤ 49 years, while transient deficits seemed to increase up to the age of 39 years, and persistent deficits showed a bimodal distribution with two peaks at age 30–39 years and age ≥ 50 years.

The frequency of any brain lesion, SAH and ICH increased regularly across age groups. IS were almost equally distributed between age groups ≥ 20 years to ≤ 59 years, and PRES occurred at all ages ≥ 20 years. CAD peaked at age 30–49 years.

When comparing young patients ≤ 49 vs patients ≥ 50 years, older patients were significantly more often affected by any brain lesion (40% vs 21%, pD < 0.001) and by SAH (35% vs 15%, pD < 0.001), while younger patients presented significantly more often with seizures (5% vs 0%, pD = 0.012) and CAD (12% vs 3%, pD = 0.008, Table 2).

Risk factors independently associated with the occurrence of neurological complications

Results of multivariable analysis are displayed in Table 3. No multivariable model was fitted for subdural hematoma because there were not enough events. After adjustment for potential confounders, increasing age was independently associated with the occurrence of any focal deficit (ORC = 1.4 [1.1–1.8], pC = 0.014). Other independent risk factors for any focal deficit were postpartum status and use of serotonergic antidepressants. Increasing age was independently associated with any brain lesion (ORC = 1.6 [1.2–2.1], pC < 0.001), SAH (ORC = 1.7 [1.3–2.3], pC < 0.001), and ICH (ORC = 1.5 [1.1–2.2], pC = 0.023). Other independent risk factors for any brain lesion were postpartum status, absence of TCH at onset, female sex, blood pressure surge and anxiety or depression, independently of the use of serotonergic antidepressants (data not shown). Age ≤ 49 years was an independent risk factor for CAD (ORD = 13.6 [2.4–76.6], pD = 0.003), alongside with hypercholesterolaemia, female sex, absence of TCH at onset and postpartum status. Increasing age was not associated with risk of ischaemic stroke or PRES (data not shown).

Functional outcome

Prognosis was good (mRS score 0–1) at 3 months for 96.5% of patients, without difference according to age groups. In univariable analysis, an unfavourable functional outcome (mRS ≥ 2) was more frequent in patients with SSRI/SNRI intake (13.5% vs 2.3%, p = 0.005), with IS (17.6% vs 2.7%, p = 0.017) and with ICH (33.3% vs 1.5%, p < 0.001). In multivariable analysis, the use of an SSRI/SNRI (OR = 5.5 [1.4–22.5], p = 0.017) and the occurrence of ICH (OR = 28.6 [7.6–107.2], p < 0.001) were independently associated with an unfavourable outcome.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that frequency and type of clinical and radiological complications in RCVS vary with age. While increasing age was independently associated with occurrence of a focal neurological deficit and haemorrhagic complications, young age was independently associated with cervical artery dissections.

We found an independent association between increasing age and the occurrence of a neurological deficit during the clinical course of RCVS. Other studies have reported transient or persistent deficits in 6–43% of RCVS cases, but none has investigated an association with age [7, 10]. Two studies examining risk factors for clinical worsening did not find an association between age and clinical worsening, while radiologic worsening was associated with advancing age [15, 23].

Seizures were associated with age ≤ 49 years in univariable analysis (pD = 0.012), but this association could not be tested in a multivariable model because seizures occurred only in patients ≤ 49 years. Of note, the strongest independent predictor for seizures was postpartum, a condition affecting only younger women. Precisely, 10/13 patients presenting with seizures were in a postpartum context. Headache and seizures are also key features of eclampsia [24], and RCVS, PRES and eclampsia are presumed to belong to the same spectrum of pregnancy-related diseases involving endothelial dysfunction as one important pathophysiological mechanism [25, 26]. RCVS should be considered as an important differential or concomitant diagnosis for new-onset postpartum seizures in order to treat patients accordingly and to prevent complications [27].

With respect to brain lesions, subarachnoid haemorrhage was the most common complication in the entire cohort, followed by intracerebral haemorrhage. This finding is in line with the results of the above-cited observational study from the 2016 US Nationwide Readmission Database, reporting haemorrhagic complications in 43% of patients [16]. The authors identified female sex as well as middle to older age-group as independent risk factors for a combined outcome of ICH, SAH and SDH. Topcuoglu et al. compared haemorrhagic and nonhaemorrhagic RCVS, and found that female sex but not age was a predictor for intracerebral haemorrhage [28]. A former analysis of the first 89 patients from our cohort identified female sex and migraine as risk factors for haemorrhagic manifestations of RCVS [29]. In the present study, the number of cases allowed for a separate analysis of ICH and SAH, revealing an independent association of increasing age with ICH as well as SAH. Of note, increasing age was the only independent risk factor for ICH in our cohort. Regarding SAH, increasing age was the most significant risk factor. Other risk factors included the absence of TCH at onset, the use of serotonergic antidepressants, female sex, postpartum status and migraine. In line with previous studies [16, 28, 29], arterial hypertension and blood pressure surge were not independently associated with haemorrhages.

Concerning possible pathophysiological hypotheses, it has been shown in the general population that age-dependent changes in the mechanical and structural properties of the vascular wall lead to loss of arterial elasticity and reduced arterial compliance [30]. Hence, age is one of the most important risk factors for intracerebral haemorrhage [31]. In RCVS, arterial stiffness related to age might reduce vasospasm tolerance, thereby increasing the risk for rupture with age.

Population-based studies have associated age-dependent vascular stiffness and risk of cardiovascular events including IS in the elderly, and one study identified increased arterial stiffness as a predictor of delayed IS in patients with SAH [32, 33]. Among patients with RCVS, an analysis of the US Nationwide Readmissions Database 2016–2017 found a higher risk for IS in patients with hypertension, diabetes and tobacco use, but no association with age [34]. Likewise, in our cohort, age was not associated with IS, but the number of IS was low and larger studies are required.

CAD showed a non-linear association with age, peaking at 30–39 years. To date, the causal and chronological relation between CAD and RCVS remains unclear and has been the subject of previous publications [35,36,37]. In summary, RCVS might induce CAD by affecting vessel wall vasa vasorum, or by increasing pressure upstream of multiple intracranial stenosis in susceptible patients. Conversely, the occurrence of CAD might cause release of vasoactive substances which trigger RCVS. Regarding the general population, the large CADISP study reported a mean age of 41 years for vertebral artery dissections and 46 years for carotid artery dissections, respectively [38]. Established risk factors for CAD comprise genetic and environmental factors, including migraine, a condition that also predisposes to RCVS [36, 39]. Hypercholesterolaemia is not a risk factor for CAD and conversely, there is no evidence that atherosclerotic plaques are protective against CAD [40]. Surprisingly, we found an association between hypercholesterolaemia and CAD during RCVS. Since only five patients had CAD and hypercholesterolaemia, larger studies are warranted. The predominance of CAD in younger patients with RCVS is not surprising. Higher elasticity of vascular walls at younger age might predispose for the occurrence of a subintimal tear with consequent blood stream between the layers of intima and media, or for intramural rupture of vasa vasorum, with subsequent dissection of the media and adventitia, respectively. Nevertheless, this finding is of relevance for clinicians since it highlights the need for adequate and sometimes repeated imaging to detect both dissections and RCVS in patients with unusual headache.

These findings are of clinical relevance for several reasons. First, knowing the frequency and type of clinical and radiological complications of RCVS as a function of age could guide the choice of required brain and vascular imaging, and the decision of inpatient or outpatient treatment. Up to now, scores have been proposed to differentiate RCVS from PACNS, and to evaluate severity of vasoconstriction, but there is no score predicting complications [41, 42]. Second, our findings further underscore the necessity to consider RCVS in patients presenting with non-aneurysmal convexity SAH (cSAH) or atypical ICH in the absence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). In a recent retrospective study on 70 patients with non-traumatic non-aneurysmal cSAH, CAA was the most common cause of unifocal cSAH, while RCVS was the commonest cause of multifocal SAH [43]. Another study of patients with cSAH found that RCVS was the most likely cause in patients ≤ 60 years whereas CAA was more likely in patients > 60 years [44]. In our cohort, 42% of patients ≥ 60 years presented with non-aneurysmal SAH, emphasizing that RCVS should also be considered in patients ≥ 60 years.

Aside from the distribution of complications, younger and older patients also differed with regards to sex, comorbidities, predisposing factors and triggers. As expected, cardiovascular comorbidities and use of serotonergic antidepressants were more frequent in older patients whereas use of illicit drugs, and sexual triggers for headache episodes were less frequent. Most importantly, the vast majority (> 90%) of the patients ≥ 50 years of age were women. In line with previous studies, these findings suggest a heterogenous spectrum of RCVS with the existence of subgroups of RCVS patients [7, 8, 10]. Young male patients often merely report use of illicit drugs, sexual triggers for headache and present a benign course of RCVS, young postpartum women seem to have higher prevalence of complications, and finally, older female patients seem to be characterised by a history of migraine, idiopathic RCVS or RCVS secondary to serotonergic antidepressants, and presence of haemorrhagic lesions on imaging. Larger studies with cluster analyses, such as conducted in transient global amnesia [45], a condition sharing numerous features with RCVS, are necessary to statistically confirm the existence of such subgroups.

The overall clinical outcome at 3 months of follow-up in our cohort was very good with an mRS score 0–1 in 96.5% of patients. Contrarily, an analysis of the US Nationwide Inpatient Database including 2020 patients with RCVS found a poor early outcome of discharge to another facility after hospitalisation or in-hospital death in one third of patients [6]. This discrepancy might be explained mainly by different recruitment patterns. While the US study described a population of hospitalised patients, two third of our patients were recruited from an emergency headache center, and one third of our patients were treated on an outpatient basis [9]. While the emergency headache center is easily accessible for any patient with a headache, capacities of our neurovascular units are restricted, thus limiting the transfer of severely affected patients from other hospitals or departments. This might have contributed to a selection bias for milder forms in our cohort with underestimation of the outcome severity. On the other hand, pure and mild cephalagic forms of RCVS might also be underrepresented, since those patients might not consult or might not return for 3 months follow-up, rendering impossible the definite diagnosis of RCVS. Overall, recruitment from two neurological wards and one emergency headache center might have balanced selection bias for milder cephalalgic vs more severe forms, respectively.

In our cohort, predictors for an unfavourable functional outcome included the use of serotonergic antidepressants prior to RCVS onset, and the occurrence of IS or ICH during RCVS. Only the use of serotonergic antidepressants and the occurrence of ICH were independent predictors. Prior studies have identified IS as the most consistent predictor [6, 15, 23, 34], and ICH as another independent predictor [6] for a poor functional outcome, underlining the importance of careful monitoring and rehabilitative measures in patients with these types of lesions. Concerning serotonergic antidepressants, prior studies have found an association with clinical and angiographic worsening but not poor outcome (defined as mRS > 3) [15]. Taken together, these findings suggest that patients with use of serotonergic antidepressants might benefit from in-hospital care allowing for close monitoring.

Contrarily to two prior studies [6, 46], we did not find an association of advanced age and an unfavourable outcome. In our cohort, patients aged > 50 years were significantly more often hospitalised. The in-patient stay might have allowed for a prevention of clinical worsening, e.g. by the means of blood pressure management and physical rest.

The main limitation of our study consists in the retrospective data acquisition for cohorts B and C. Further, although we describe the largest European cohort to date, the numbers for some subtypes of complications remain small. This possibly contributes to the inconsistency of findings between the different cohorts published to date, and future larger multi-centric studies could be suited to confirm or refute clinical and radiological predictors of complications and of an unfavourable functional outcome. Moreover, since we included only adult patients aged ≥ 15 years from two French hospitals, our findings may not be applicable to other populations and to pediatric patients. Finally, we have not compared the localisation, degree and number of vasospasms, possibly varying according to age and influencing the risk for complications.

Conclusion

Among adult patients with RCVS in France, rates and types of complications vary according to age. While young age was associated with CAD, increasing age predisposed for haemorrhagic complications. Larger multi-center studies are necessary to confirm possible age-specific presentations of RCVS and should consider age when developing prognostic scores helping to guide clinical decision-making.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADC:

-

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- CAA:

-

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CAD:

-

Cervical artery dissection

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- EHC:

-

Emergency headache center

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- ICH:

-

Intracerebral haemorrhage

- IS:

-

Ischaemic stroke

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance tomography

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance angiography

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ORC :

-

Odds ratio, age used as a continuous variable

- ORD :

-

Odds ratio, age used as a dichotomous variable

- p C :

-

p Value, age used as a continuous variable

- p D :

-

p Value, age used as a dichotomous variable

- PRES:

-

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

- RCVS:

-

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

- cSAH:

-

Convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDH:

-

Subdural haematoma

- SSRI:

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- SNRI:

-

Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

- SWI:

-

Susceptibility-weighted imaging

- TCH:

-

Thunderclap headache

References

Ducros A (2012) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Lancet Neurol 11:906–917

Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB (2007) Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med 146:34–44

Sanchez-Montanez A, Morana G, Mancardi MM et al (2015) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction mimicking posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in an infant with end-stage renal disease. Cephalalgia 35:1031–1033

Coffino SW, Fryer RH (2017) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome in pediatrics: a case series and review. J Child Neurol 32:614–623

de Boysson H, Parienti JJ, Mawet J et al (2018) Primary angiitis of the CNS and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a comparative study. Neurology 91:e1468–e1478

Patel SD, Topiwala K, Otite Oliver F et al (2021) Outcomes among patients with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a nationwide United States analysis. Stroke 52:3970–3977

Singhal AB, Hajj-Ali RA, Topcuoglu MA et al (2011) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes: analysis of 139 cases. Arch Neurol 68:1005–1012

Caria F, Zedde M, Gamba M et al (2019) The clinical spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: The Italian Project on Stroke at Young Age (IPSYS). Cephalalgia 39:1267–1276

Lange KS, Forster O, Mawet J et al (2022) Type of headache at onset and risk for complications in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Eur J Neurol 29:130–137

Choi HA, Lee MJ, Choi H, Chung CS (2018) Characteristics and demographics of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a large prospective series of Korean patients. Cephalalgia 38:765–775

Chen SP, Fuh JL, Lirng JF, Wang YF, Wang SJ (2015) Recurrence of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a long-term follow-up study. Neurology 84:1552–1558

Shimoda M, Oda S, Shigematsu H et al (2018) Clinical significance of centripetal propagation of vasoconstriction in patients with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a retrospective case–control study. Cephalalgia 38:1864–1875

Erhart DK, Ludolph AC, Althaus K (2023) RCVS: by clinicians for clinicians—a narrative review. J Neurol 270:673–688

Wilson D, Marshall CR, Solbach T, Watkins L, Werring DJ (2014) Intraventricular hemorrhage in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. J Neurol 261:2221–2224

Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA (2017) Glucocorticoid-associated worsening in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Neurology 88:228–236

Patel SD, Topiwala K, Saini V et al (2021) Hemorrhagic reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a retrospective observational study. J Neurol 268:632–639

Boitet R, de Gaalon S, Duflos C et al (2020) Long-term outcomes after reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Stroke 51:670–673

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2013) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33:629–808

Weisscher N, Vermeulen M, Roos YB, de Haan RJ (2008) What should be defined as good outcome in stroke trials; a modified Rankin score of 0–1 or 0–2? J Neurol 255:867–874

Silberstein SD, Merriam GR (1993) Sex hormones and headache. J Pain Symptom Manage 8:98–114

Al-Hassany L, Haas J, Piccininni M, Kurth T, Maassen Van Den Brink A, Rohmann JL (2020) Giving researchers a headache—sex and gender differences in migraine. Front Neurol 11:549038

Topcuoglu MA, McKee KE, Singhal AB (2016) Gender and hormonal influences in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Eur Stroke J 1:199–204

Katz BS, Fugate JE, Ameriso SF et al (2014) Clinical worsening in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. JAMA Neurol 71:68–73

FishelBartal M, Sibai BM (2022) Eclampsia in the 21st century. Am J Obstet Gynecol 226:S1237-s1253

Fletcher JJ, Kramer AH, Bleck TP, Solenski NJ (2009) Overlapping features of eclampsia and postpartum angiopathy. Neurocrit Care 11:199–209

Chen SP, Wang SJ (2022) Pathophysiology of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. J Biomed Sci 29:72

Aya AG, Ondze B, Ripart J, Cuvillon P (2016) Seizures in the peripartum period: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 35(Suppl 1):S13-s21

Topcuoglu MA, Singhal AB (2016) Hemorrhagic reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: features and mechanisms. Stroke 47:1742–1747

Ducros A, Fiedler U, Porcher R, Boukobza M, Stapf C, Bousser MG (2010) Hemorrhagic manifestations of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: frequency, features, and risk factors. Stroke 41:2505–2511

Jani B, Rajkumar C (2006) Ageing and vascular ageing. Postgrad Med J 82:357–362

Ariesen MJ, Claus SP, Rinkel GJ, Algra A (2003) Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population: a systematic review. Stroke 34:2060–2065

Sutton-Tyrrell K, Najjar SS, Boudreau RM et al (2005) Elevated aortic pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness, predicts cardiovascular events in well-functioning older adults. Circulation 111:3384–3390

Acampa M, Bongiorno M, Lazzerini PE et al (2021) Increased arterial stiffness is a predictor of delayed ischaemic stroke after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Heart Lung Circ 30:525–530

Garg A, Starr M, Rocha M, Ortega-Gutierrez S (2021) Predictors and outcomes of ischemic stroke in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. J Neurol 268:3020–3025

Mawet J, Boukobza M, Franc J et al (2013) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and cervical artery dissection in 20 patients. Neurology 81:821–824

Mawet J, Debette S, Bousser MG, Ducros A (2016) the link between migraine, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and cervical artery dissection. Headache 56:645–656

Topcuoglu MA, Kursun O, Singhal AB (2017) Coexisting vascular lesions in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Cephalalgia 37:29–35

Debette S, Grond-Ginsbach C, Bodenant M et al (2011) Differential features of carotid and vertebral artery dissections: the CADISP study. Neurology 77:1174–1181

Debette S, Leys D (2009) Cervical-artery dissections: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and outcome. Lancet Neurol 8:668–678

Debette S, Metso T, Pezzini A et al (2011) Association of vascular risk factors with cervical artery dissection and ischemic stroke in young adults. Circulation 123:1537–1544

Rocha EA, Topcuoglu MA, Silva GS, Singhal AB (2019) RCVS(2) score and diagnostic approach for reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Neurology 92:e639–e647

Chen SP, Fuh JL, Wang SJ et al (2010) Magnetic resonance angiography in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Neurol 67:648–656

Dakay KB, Azher I, Mahta A, Furie K, Yaghi S, Cutting SM (2021) Multifocal atraumatic convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cureus 13:e16091

Kumar S, Goddeau RP Jr, Selim MH et al (2010) Atraumatic convexal subarachnoid hemorrhage: clinical presentation, imaging patterns, and etiologies. Neurology 74:893–899

Quinette P, Guillery-Girard B, Dayan J et al (2006) What does transient global amnesia really mean? Review of the literature and thorough study of 142 cases. Brain 129:1640–1658

Song TJ, Lee KH, Li H et al (2021) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a comprehensive systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25:3519–3529

Acknowledgements

This study was not sponsored. The authors would like to thank Dr. Alexandra Macgregor for proofreading the article.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was not sponsored.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KSL, GT, AD and JM researched literature and conceived the study. KSL, JM and AD were involved in gaining ethical approval. KSL, GT, CG, CB, CR, AD and JM were involved in data collection. KSL and CD were responsible for statistical analyses and data visualisation. KSL wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in data interpretation, reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

KSL received travel and accommodation expenses from Acticor Biotech and Teva, not related to the submitted work. CR received honoraria for board membership and speaker fees Allergan/Abbvie, Homeperf, Lilly, Lundbeck, Mylan, Novartis, Ophtalmic, Orkyn, Pfizer, Sanofi and Teva, and travel, accommodation, and meeting expenses from Teva, Lundbeck and Lilly, all outside the submitted work. AD received honoraria for board membership and speaker fees from Allergan Abbvie, Lilly, Teva, Lundbeck, Pfizer and travel, accommodation, and meeting expenses from Teva, and SOS Oxygène, all outside the submitted work; she is associate editor of Cephalalgia. JM received travel, accommodation, and meeting expenses from SOS, GEP Sante, Lundbeck and Homeperf and received honoraria for advisory boards or speaker fees from Abbvie, Teva, Lilly, Lundbeck and Novartis not related to the submitted work; he is a member of the redaction committee of “La Lettre du Neurologue” without financial compensation. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the prospectively recruited patients for their anonymized information to be published. Informed consent was waived for the retrospectively included patients.

Ethical approval

The Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté and the local ethics committee of the University Hospital Montpellier approved this study (REC number: 202100733).

Guarantor

KSL.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lange, K.S., Tuloup, G., Duflos, C. et al. Complications of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome in relation to age. J Neurol 270, 3584–3594 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11708-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11708-z