Abstract

Objective

Compassion is widely regarded as an important component of high-quality healthcare. However, its conceptualization, use, and associated outcomes in the care of people with multiple sclerosis (PwMS) have not been synthesized. The aim of this review is to scope the peer reviewed academic literature on the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS.

Methods

Studies were eligible for inclusion if reporting primary research data from quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies on the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS. Relevant studies were identified through searching five electronic databases (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO) in January 2022. We followed the guidance outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) manual for evidence synthesis, and also referred to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist (PRISMA-ScR). Simple descriptive methods were used to chart quantitative findings, and a descriptive approach with basic content analysis was employed to describe qualitative findings.

Results

Fifteen studies were included (participant n = 1722): eight quantitative, six mixed-methods, one exclusively qualitative. Synthesized qualitative data revealed that PwMS conceptualize compassion as involving self-kindness, agency, and acceptance. PwMS report using self-compassion in response to unpleasant sensations and experiences. Quantitative findings suggest that compassion may mediate benefit finding, reduced distress, and improved quality of life (QoL) in PwMS, that those with the condition may become more compassionate through time, and that self-compassion specifically can be increased through training in mindfulness. In this context, greater self-compassion in PwMS correlates with less depression and fatigue, better resilience and QoL. Among studies, self-compassion was the most common outcome measure for PwMS.

Conclusions

A nascent literature exists on the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS. Further research is required to better understand what compassion means to PwMS and those caring for them. However, self-compassion can be cultivated among PwMS and may be helpful for managing unpleasant somatic symptoms and in benefit finding. Impact on other health outcomes is less clear. The use of compassion by health care providers in the care of PwMS is unstudied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive, neurodegenerative condition typically diagnosed between 20 and 40 years of age [1]. Around the world, incidence and prevalence of MS are increasing [2]. MS is an expensive condition, both for PwMS and for health services [3]. In the early stages, disease-modifying treatments are associated with most cost. As the condition progresses, social care costs dominate. However, around a third of all costs relate to intangible costs, deriving from patient suffering (stress, pain, fatigue), the so-called ‘hidden symptoms’ [4]. Indeed, people with multiple sclerosis (PwMS) commonly describe the condition as stressful, yet highlight how emotional aspects of care are frequently overlooked by their healthcare providers (HCPs) [5]. Stress is toxic for PwMS, increasing rates of anxiety and depression, and lowering quality of life (QoL) [6]. Unfortunately, effective mental health treatments for PwMS are limited, with current evidence favoring cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) [7, 8]. How CBT and MBIs improve stress, anxiety, and depression in PwMS is not entirely clear, though for MBIs compassion for oneself appears to play a mediatory role [9, 10]. Given the high prevalence of mental health impairment in PwMS, relative lack of effective treatments, and elevated care costs associated with hidden symptoms, it is important to explore novel treatments and self-management strategies that are acceptable, effective, affordable, and sustainable.

Compassion is a widely debated subject [11,12,13]. It has been defined empirically as the recognition of suffering in another coupled with a deep desire to alleviate that suffering [14]; and this latter aspect of compassion is suggested to differentiate it from empathy, which need not be coupled with a desire to alleviate suffering [15]. The empirical definition echoes earlier philosophical descriptions; Schopenhauer saw compassion as innate, being the basis for non-egoistic morality, justice and loving kindness [16]. From a biological perspective, compassion is thought to have evolved in mammals by necessity, to facilitate increased ‘in-group’ survival [17].

Compassion commonly features in mission statements and competency frameworks in many professional healthcare organizations [18,19,20], is regarded as an important component of quality healthcare [21], is widely taught in health professional education [22], and can be improved through targeted education [11, 23]. When patients perceive their HCP to be more empathic and compassionate, they report improved outcomes for stress, anxiety, depression, and pain [24]. Of concern, those medical specialists who routinely care for PwMS i.e., Neurology, Rehabilitation Medicine, and Primary Care providers are reported to have high levels of compassion fatigue [25] and burnout [26, 27]. which can lower empathic concern and compassionate responding through increased stress, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization [28]

Both mindfulness- and compassion-based interventions can effectively reduce burnout and improve compassionate care in HCPs [29, 30]. Among patients (non-MS populations), interventions designed to cultivate compassion or self-compassion are associated with improvements in anxiety, depression, pain, and QoL [31, 32]. Indeed, in long term neurological conditions other than MS, greater self-compassion is correlated with improved resilience to stress, anxiety, and depression [33], though for unclear reasons effects are much smaller among those with chronic diseases, when compared to the general population [34].

To our knowledge, the academic literature on the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS has not been synthesized previously, and the aim of this scoping review is to map the existing evidence in this area.

Methods

The protocol for this scoping review was registered on the Open Science Framework Register on January 13, 2022, Registration https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/M5PHF. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for scoping reviews [35] as a guiding framework, and referred to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist (PRISMA-ScR) [36].

Developing a search strategy

An initial search of the included databases was conducted, allowing analyses of text and index terms to be used across identified articles. Identified terms were integrated into our search strategy. Lastly, five databases were searched (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO), with medical subject headings and key words relating to compassion and MS, using controlled vocabulary, search symbols, and Boolean operators.

Evidence screening and selection

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if reporting primary research data in English, from any year, inclusive of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods findings on the conceptualization, use, and/or outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS. If including other health conditions, data had to be extractable for PwMS specifically.

Screening and selection

We used Endnote and Covidence to store, screen, and sort results. Two reviewers (SP, RS) independently screened titles and abstracts of bibliographic records derived from the search. After removing duplicates, two reviewers conducted title and abstract review. Pilot testing of source selectors was conducted by assessing a random sample of 25 titles/abstracts, where our research team screened these using our eligibility criteria. We undertook full screening only once our team achieved > 80% agreement. Our agreement was defined by Cohen’s Kappa, κ = 0.83.

Data extraction

Included studies were charted by two independent reviewers using the JBI manual data extraction template [37]. First, we performed a pilot extraction, whereby we trialed the extraction template for 2–3 sources to ensure all relevant results were being extracted. The following data were extracted: author(s), publication year, country, study aims, study type, methodology/methods, population/sample size, intervention/comparator, outcomes, and findings relating to the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS.

Analysis

Simple descriptive methods were used to chart the quantitative data, and a descriptive approach with conventional content analysis was undertaken to describe qualitative data [38]. An assessment of study quality was deemed overly complex with little added value given the wide ranging nature of study designs; an acceptable approach within scoping review methodology [36].

Results

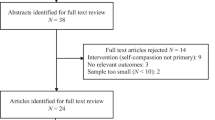

Our search in January 2022 generated 1145 ‘hits’. Following de-duplication, there were 919 records. After title and abstract screening, 16 full text studies were deemed eligible, retrieved, and reviewed; however, one was a duplicate study. Thus, 15 articles were included in the final review. Search results are detailed in Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Moher et al. [53]

Study characteristics

Eight studies used a quantitative methodology; one a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [39], four used cross-sectional surveys [40,41,42,43], one a longitudinal survey [44], one was a ‘unicentric prospective observational cohort study’ [45], and one a ‘cross sectional naturalistic design’ [46]. Six studies utilized a mixed-methods approach; one a ‘parallel pilot RCT and qualitative interview study’ [10], one a ‘pilot study’ with a single intervention condition [47], one described as a ‘quali-quantitative survey’ [48], one study comprised surveys and interviews [49], and two studies undertook respectively process and implementation analyses for an RCT [50, 51]. Lastly, one study adopted a qualitative approach using interviews [52]. Nine studies were conducted in Europe [10, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 50, 51], two in Australia [44, 47], two in Asia [40, 52], one in the United States [43], and one between the United States and Europe (Table 1) [49].

Participant characteristics

The majority of included studies were comprised exclusively of PwMS [10, 39,40,41, 43, 47, 49, 50, 52]. Two studies also included healthy volunteer controls [42, 45] and another included PwMS and their ‘carers’ [44, 46]. Two studies featured MS clinicians [48, 51]. Disability was characterized according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) in eight studies [10, 39, 41, 42, 45, 49,50,51]. Of these, seven reported mean (SD) EDSS [10, 39, 41, 42, 45, 49, 51], which ranged from 1.51 (1.63) to 6.8 (1.6). One study reported an EDSS range of 1.0–7.0 [50]. Two studies reported ‘levels of severity of disease’ [40, 52], while two reported disability through the Activities of Daily Living Self-Care Scale for Persons with MS [44, 47]. Two studies did not measure disability, but rather general health [46] or health status [43]. In one study, participants were exclusively comprised of HCPs [48]. Participant ethnicity was reported in six studies [10, 39, 43, 45, 50, 51], with most participants being “White” or “Caucasian”. All but one study reported participant age [52], with most participants having an age range between 21 and 66, and median age between 40 and 50 across all studies. Participant sex was reported in all studies, with % female ranging between 57.3 and 94.0%. Four studies from Europe reported on socioeconomic status (SES); in one ‘middle class workers prevailed’ [45]; in another, 61% of participants perceived their income as ‘moderate’ [41]; another reported ‘postcode-derived SES of 4’ (on a scale of 1–10, 1 delineating the most deprived, 10 the least) [51] and a further study included participants ranging from the ‘most deprived’ to the ‘most affluent’ [50]. Education level was reported in 12 studies, with eight reporting that most participants completed higher education, university or college [10, 39, 41, 44,45,46, 50,51,52], three reporting that most participants had completed high school [40, 42, 49], and one reporting that most participants completed ‘TAFE/apprenticeship’ [47]. Across studies, the sample size ranged from 23 to 620, with a total of 1722 participants (Table 2).

Intervention characteristics and adherence

Five studies were interventional [10, 39, 47, 50, 51], all being “Mindfulness-based”—with the aim being to decrease distress and improve psychological well-being. Each intervention occurred over 8 weeks, with sessions ranging from 1- to 2.5-h duration, and were facilitated by psychologists or physicians. One intervention ran virtually, over Skype [10], one was conducted across different community-based venues [47], and three were held in a medical clinic [39, 50, 51]. In the parallel pilot mixed-methods study from Europe, all participants completed four (or more) of eight sessions. In the pilot study from Australia, 80% of participants attended four to five of five sessions. In the RCT from Europe, 60% of participants met the criteria for course completion (> 4 sessions). Of the two mixed-methods studies conducted following a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) intervention, one reported that 17% of participants did not complete the course [51], while the other reported 18% attrition (Table 3) [50].

Conceptualization of compassion in the care of PwMS

Compassion and compassion-related constructs were explicitly defined a priori in eight studies [10, 40, 41, 43, 46,47,48, 52]. Posteriori conceptualizations across studies solely spoke to the construct of self-compassion [10, 47, 50,51,52].

Among a priori definitions, self-compassion was defined most often (n = 7) [10, 40, 41, 43, 46, 47, 52], followed by compassion (n = 1) [46], and compassion fatigue (n = 1) [48]. Each construct was reflected in the process measures chosen within respective studies. Across studies, compassion was measured using a variety of validated outcome measures, including the Self-Compassion Scale-short form [10, 33], the Self-Compassion Scale [35,36,37, 40, 41], and the Compassion Scale [40]. One study utilized a non-validated ‘self-compassion researcher-made questionnaire’ [34]. Other studies used proxy measures for compassion, such as compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue [48], the DECAS [Deschidere (Openness), Extraversiune (Extraversion), Conştiinciozitate (Conscientiousness), Agreabilitate (Agreeableness)] Personality Inventory [39], and the Benefit Finding in Multiple Sclerosis Scale (BFiMSS) [38, 43]. Other quantitative outcomes evaluated in relation to compassion included acceptance, QoL, distress, perceived stress, and self-esteem.

In qualitative analyses with posteriori conceptualizations, self-compassion was described as involving an awareness of the need to care for oneself and indeed to be an active agent in this sense, [52] whereas adopting self-kindness towards one’s psychological state and physical body were characterized by acceptance, and the active distillation of negative self-talk and self-criticism [10, 47]:

“The course taught me so much more about myself & helped me accept my experience” [47]

Use of compassion in the care of PwMS

The use of compassion in the care of PwMS was discussed both in terms of relating to oneself (self-compassion) and in relation to others. Self-compassion was often used during mindfulness training to allow PwMS to replace prior tendencies towards self-judgment and criticism. For example, in a mixed-methods study from Europe, PwMS reported that mindfulness training aided them in developing a sense of compassion and self-directed kindness, rather than feelings of “guilt” and patterns of “negative self-talk” that they experienced previously [10]. One participant reported that she could now, “actually do things on my own and be happy with my own company” rather than seeking comfort and assurance from others [10, 50]. In a qualitative study from Asia, mindfulness was evoked by PwMS as being a component of self-compassion, in which one could actively replace ruminating on the “negative impacts” of MS with “self-construction and turning the bad feeling into good ones” where self-kindness included “not blaming self because of the disease” [52]. In another mixed-methods study from Europe, PwMS reported that mindfulness training allowed them to learn more about themselves and helped them to “accept their experience” living with illness [47]. Notably, PwMS reported initial difficulties channeling a sense of self-compassion during somatically focused mindfulness practices but that this “changed over time” as individuals eventually felt more “accepting” and “self-compassionate” towards themselves. Another mixed-methods study from Scotland, also reported that PwMS found being attentive to bodily sensations increased awareness of MS symptoms, but that eventually “this initial discomfort with coming face-to-face with their MS changed over time, into a more accepting and self-compassionate approach” [50]. In one case, a participant recounted how he was able to replace a previously automatic anger response to painful muscle spasms with equanimity instead:

“An awful lot of MS people, we get really bad sort of spastic muscle spasms and I used to get so angry . . . you know sort of like shouting and swearing and things because there is nothing you can do except wait until it goes, but I learned to be calmer about the episodes, more gentle about it and that really worked very well and that still works” [50].

A compassionate approach towards one’s experience was also used by PwMS in response to impaired mobility, evoking the idea that for PwMS there may at times be a somatic or functional trigger to practice self-compassion. For example, PwMS reported that while mobility difficulties previously led to negative self-talk and self-blame, such moments now served as a reminder to practice self-compassion [10]

In quantitative analyses, PwMS were reported to present themselves in a more passive and compassionate manner compared to healthy controls, which the authors suggested may predispose PwMS to practice social compliance to avoid conflict [45].

Outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS

Outcomes among PwMS

Across several studies, self-compassion among PwMS varied with self-esteem, mental health diagnoses, QoL, and level of disability. In a mixed-methods study from Europe, participants reported gains in compassion towards oneself since being diagnosed with MS, independent of sex, gender, and ethnicity [49]. In a longitudinal survey study from Australia, factor analysis of the BFiMSS revealed that compassion/empathy was linked to finding benefits within the context of an MS diagnosis, where increased age and time since diagnosis were weakly linked to greater compassion/empathy [44]. A cross-sectional study from Bulgaria indicated that although total self-compassion scores among PwMS did not differ compared with healthy controls, scores on self-compassion subscales did differ according to one’s level of disability. Specifically, those PwMS with the highest level of disability reported greatest self-kindness and lowest self-judgment, while healthy controls reported greatest self-judgment and lowest self-kindness [42].

In other cross-sectional studies, self-compassion was also linked with a variety of physical and mental health outcomes in PwMS. A study from Spain found that after ‘strict confinement’ due to COVID-19, self-compassion among PwMS was significantly and positively correlated to physical role, social function, vitality, and global health, and negatively correlated with global fatigue and cognitive fatigue [46]. A study from Iran found direct, but statistically insignificant correlations between self-esteem and various subscales of self-compassion, such as self-kindness, and self-judgment [40]. A study from Turkey revealed that non-depressed PwMS had higher self-compassion scores and better QoL compared to those with depression [41]. In another study, compassion was positively related to anxiety and inversely related to depression [44]. A study from the USA found that self-compassion was significantly correlated with QoL as well as resilience [43]. In a study from the UK, self-compassion had small mediation effects in lessening distress immediately following an MBI, with moderate sized effects at follow-up [10]. In a study from Australia, total scores on the Self-Compassion Scale increased for PwMS following an MBI, while in a study from Scotland, significant, large, and sustained effect sizes were evident for self-compassion immediately following an MBI and 3 months later [39].

Outcomes among caregivers of PwMS

A longitudinal study from Australia found that factors of the BFiMSS had external validity, as caregiver ratings of benefit finding were positively, and significantly correlated with BFiMSS factors, including compassion/empathy, and overall score among PwMS [44]. In addition, results from a cross-sectional study from Spain indicated that caregivers of PwMS had ‘high’ compassion scores, and that such scores were not significantly correlated to their mental, physical, global health, or fatigue [46].

Outcomes among HCPs of PwMS

Healthcare provider (HCP) compassion for PwMS was not measured directly in any study. However, in a study from Italy, differences in compassion fatigue emerged according to HCP role as well as age. Specifically, neurologists, compared to nurses, had lower compassion satisfaction and an elevated risk of burnout, although both groups reported high levels of compassion fatigue. Younger (< 45 years old) HCPs had lower compassion satisfaction (i.e., derived less fulfillment from vocational role) in caring for PwMS and higher burnout, although both groups had high levels of compassion fatigue [48].

Table 4 provides an overview of the conceptualization, use, and outcomes of compassion in the care of PwMS.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This scoping review has explored the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS. Among studies included in this review, compassion was most often conceptualized based on established, a priori definitions, including compassion in relation to oneself and, as is more traditional, towards others. However, posteriori definitions exclusively described self-compassion, conceptualized as involving self-kindness towards one’s psychological and physical being, abandonment of self-criticism, acceptance, and a sense of agency. Quantitative findings suggest that greater compassion may mediate benefit finding, reduced distress, and better QoL among PwMS, that those with the condition become more compassionate through time, and that self-compassion specifically can be increased through training in mindfulness. In terms of outcomes, greater self-compassion among PwMS correlates with less depression and fatigue, better resilience and QoL.

Comparison to existing literature

Conceptualization of compassion

Considerable debate remains as to the construct of compassion and its conceptualization generally [11, 55]. In the context of MS, very little data exists on how PwMS conceptualize compassion from others, or how HCPs use compassion in caring for those with the condition. This latter point is a notable finding, in part because more general evidence syntheses suggest that compassion is most often studied in HCPs and much less so among patients [11], but also because PwMS value when HCPs attune to their emotional needs and take steps to address their distress [5, 56]. Indeed, PwMS report how a perceived lack of empathy from HCPs weighs heavily in the ‘cost’ they consider when deciding whether or not to seek out help through mainstream health services [57]. This is problematic for many reasons. Firstly, the needs of PwMS are complex and are accentuated at times of greatest stress, such as at diagnosis, during a relapse, or as disability progresses [58,59,60,61,62]. Secondly, many of the symptoms of MS are ‘hidden’ [63] and therefore may go unnoticed by HCPs, perhaps explaining the lack of attention as perceived by PwMS. However, as the empirical definition of compassion depends upon the recognition of suffering in another, it seems crucially important that HCPs know to ask about ‘hidden’ suffering, even if not apparent on superficial review, besides how to respond [with compassion] when hidden suffering does exist. If such needs are not met in mainstream services, PwMS may end up paying out of pocket for alternative treatments [64, 65] where providers may be perceived as having better ‘listening skills’ and demonstrating ‘more care and concern’ [66].

The debate as to the conceptualization of compassion generally notwithstanding, it seems important to better understand what compassion means to PwMS and their HCPs. This type of study has been done previously in palliative care, using a Grounded Theory approach, with findings suggesting distinct and overlapping meanings for compassion between patients and HCPs [67, 68]. Pursuing such an approach would appear beneficial in informing care optimization for PwMS, given the current mismatch reported between what care PwMS want, versus what they receive [5, 56, 57, 62].

Use of compassion

In terms of how compassion is used in the care of PwMS, findings suggest that self-compassion is an important factor in the adjustment process, where benefit finding plays a part in discovering positive perspectives on life because of, or in spite of, having MS. This fits with the general academic literature on benefit finding, where factor analysis has previously confirmed compassion as an important component in this complex, multifactorial process, along with conceptually similar post-traumatic growth models [69]. However, besides training in MBIs, which addresses compassion broadly and, arguably, indirectly [9], from this review of the literature it seems that compassion is not being used explicitly in the care of PwMS, by either HCPs or caregivers.

Compassion should, in theory, be a core part of HCP treatment of PwMS. However, high levels of compassion fatigue and burnout are reported in key specialties caring routinely for PwMS, including Neurology [70], Rehabilitation Medicine [26], and Primary Care [27], a scenario likely to have been accentuated greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Known drivers of compassion fatigue and burnout (time constraints, inadequate staffing, excessive workload, care fragmentation, use of technology, lack of resources, organizational culture) [71] have also been identified as common barriers to the delivery of compassionate care [11]. Compassion fatigue and HCP burnout matter because they are associated with reduced productivity, lower quality patient care, and worse health in HCPs, increased risk of medical errors, increased costs, and lower patient satisfaction [71]. Interventions for compassion fatigue and burnout need to be multifaceted to be effective [72], but arguably should include compassion-based interventions [22, 29, 73, 74]. However, how compassion is defined in this context needs to be considered carefully [75, 76] as the link between the empirical definition of compassion [14, 75] and compassion fatigue, although perhaps intuitive, is scientifically tenuous at best [77].

Only one study in this review addressed the role of compassion among PwMS within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [46]. Further study in this area may be beneficial, as in the general population, greater perceived compassion from others and towards one’s self are associated with less psychological distress and fears of contracting COVID-19 [78]. Virtual interventions to facilitate increased self-compassion among PwMS may represent an effective way of addressing the surge of psychological distress reported by PwMS during the COVID-19 pandemic [79, 80]. Online MBIs appear to be acceptable to PwMS [81], are effective at reducing stress [82, 83] and improving self-compassion [69], but do not have compassion as the core focus of treatment and compassion-based interventions may be more effective at improving compassion specifically [9].

Nevertheless, mindfulness and compassion in the care of PwMS appear linked, in that MBI training is associated with an increase in levels of self-compassion while course participants also describe a newfound sense of care and concern for an ailing body. Qualitative research findings in this review certainly suggest that MBI training can help PwMS to develop a more compassionate approach toward themselves, and in relation to others, which may be associated with improved interpersonal functioning and social supports, and fits with existing evidence in general that MBI training is an effective way of improving compassion [29], prosociality [84], and interpersonal relationships [54]. However, learning to be compassionate towards oneself and/or others may take time develop and those PwMS who are older and more disabled report being more compassionate in comparison to younger and less disabled counterparts. When viewed as part of a longitudinal adjustment process, this finding may in part be explained by MS being a ‘moving target’ [85, 86]; particularly in the early stages where fluctuations in disease activity, treatment regimens, and distressing symptoms can be pronounced [87, 88], and present the greatest challenges socially [89, 90].

Outcomes of compassion

In terms of outcomes, the measurement of compassion among PwMS is a relatively nascent area. Quantitative measures most commonly included the Self-Compassion Scale, which is a six-factor scale including dimensions of self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification [91]. Although widely validated in the non-MS literature, this measure has not been validated specifically for use among PwMS, which matters because generic well-being outcome measures may fail to capture what matters most to those affected with MS [92]. Furthermore, the lack of empirical validation for PwMS limits interpretation of findings, in that although there may be face validity for the construct of compassion in the context of managing MS, we cannot be sure about the ecological validity and reliability of the measurement scales in this specific population, as this has not been empirically tested.

Lastly, it is important to determine the outcomes of compassion among caregivers of PwMS. Within the literature examining the experiences of caregivers for older adults, and individuals with dementia, compassion is often linked to compassion fatigue [93,94,95,96]. Findings from this review suggest that the experiences of caregivers’ of PwMS are not linked to their QoL and well-being [46], but further research is needed to examine specifically the link between compassion and caregiver well-being within the context of caring for a person with MS.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review provides a comprehensive examination of the evidence for the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS. In keeping with the general literature on compassion in healthcare [11], findings from this current review highlight gaps in the evidence base, such as the paucity of RCTs assessing the effectiveness of compassion as an intervention for improving outcomes for PwMS, or even more generally how compassion is used by HCPs in caring for PwMS. A wide range of validated measures of compassion have been applied to PwMS but have not been validated in this population per se. Lastly, participants across included studies were mainly “white”. This raises the question of how compassion in the care of PwMS from diverse ethnic and racial groups is conceptualized, used, and measured, prompting the need for cultural humility and targeted research across more diverse populations. For example, among some cultures compassion may not be viewed positively in a healthcare context [97].

Implications

Preliminary conceptualizations of compassion among PwMS have been identified in this scoping review, but more qualitative research is needed to better conceive of the meaning of compassion in the care of PwMS, particularly from the perspectives of care partners and HCPs. Once a clear conceptualization is made, then use and outcomes may be more closely scrutinized. Lastly, there is a need to test compassion-based interventions within the context of MS, as most of the synthesized literature reports on MBIs, in which compassion is only a component part [9]. HCPs may wish to consider how to acquire skills in compassion for them to use in their clinical practice, besides how to train PwMS in self-compassion, which seems particularly promising. Recent systematic review evidence on the nature of compassion education reported a large variety of ‘humanities-based reflective practices’ to facilitate learning about compassion in the context of healthcare [22]. Training practices included reflexive writing, visual analysis of images, watching movies and listening to music [22]. Additional studies indicate that role play and mindfulness may facilitate the cultivation of compassion [73, 98]

Conclusion

A nascent literature exists on the conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of PwMS. Further research is required to better understand what compassion means to PwMS and those caring for them. However, self-compassion can be cultivated among PwMS and may be helpful for managing unpleasant somatic symptoms and in benefit finding. Impact on other health outcomes is less clear. The use of compassion by health care providers in the care of PwMS is unstudied.

References

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F et al (2018) Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 17(2):162–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2

Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C et al (2014) Atlas of multiple sclerosis 2013: a growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology 83(11):1022–1024. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000768

Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C et al (2011) Treatment experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in multiple sclerosis: the costs and utilities of MS patients in Canada. Journal of population therapeutics and clinical pharmacology = Journal de la therapeutique des populations et de la pharamcologie clinique 19(1):e11–e25

Wundes A, Brown T, Bienen EJ et al (2010) Contribution of intangible costs to the economic burden of multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ 13(4):626–632. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2010.525989

White CP, White M, Russell CS (2007) Multiple sclerosis patients talking with healthcare providers about emotions. J Neurosci Nurs 39(2):89–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-200704000-00005

Wollin JA, Spencer N, McDonald E et al (2013) Longitudinal changes in quality of life and related psychosocial variables in Australians with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 15(2):90–97. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2012-032

Reynard AK, Sullivan AB, Rae-Grant A (2014) A systematic review of stress-management interventions for multiple sclerosis patients. Int J MS Care 16(3):140–144. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2013-034

Simpson R, Simpson S, Ramparsad N et al (2019) Mindfulness-based interventions for mental well-being among people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 90(9):1051–1058. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-320165

Roca P, Vazquez C, Diez G et al (2021) Not all types of meditation are the same: Mediators of change in mindfulness and compassion meditation interventions. J Affect Disord 283:354–362

Bogosian A, Hughes A, Norton S et al (2016) Potential treatment mechanisms in a mindfulness-based intervention for people with progressive multiple sclerosis. Br J Health Psychol 21(4):859–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12201

Malenfant S, Jaggi P, Hayden KA et al (2022) Compassion in healthcare: an updated scoping review of the literature. BMC Palliat Care 21(1):1–28

White R (2017) Compassion in philosophy and education. The pedagogy of compassion at the heart of higher education. Springer, pp 19–31

Strauss C, Taylor BL, Gu J et al (2016) What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin Psychol Rev 47:15–27

Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E (2010) Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull 136(3):351

Stevens L, Woodruff C (2018) The neuroscience of empathy, compassion, and self-compassion. Academic Press

Schopenhauer A (1998) On the basis of morality. Hackett Publishing

De Waal FB, Preston SD (2017) Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nat Rev Neurosci 18(8):498–509

Ontario CoPaSo (2022) Advice to the Profession: Professional Obligations and Human Rights CPSO website. https://www.cpso.on.ca/Physicians/Policies-Guidance/Policies/Professional-Obligations-and-Human-Rights/Advice-to-the-Profession-Professional-Obligations. Accessed Mar 23 2022.

Ontario RCoPaSo (2022) Compassion and caring RCPSC website. https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/framework/canmeds-role-professional-e. Accessed Mar 23 2022.

Fiske A, Henningsen P, Buyx A (2019) Your robot therapist will see you now: ethical implications of embodied artificial intelligence in psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy. J Med Internet Res 21(5):e13216

Organization WH (2020) Quality Health Services 2020, 2020.

Sinclair S, Kondejewski J, Jaggi P et al (2021) What is the state of compassion education? A systematic review of compassion training in health care. Acad Med 96(7):1057

Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S et al (2019) Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 14(8):e0221412

Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen ALM (2013) Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 63(606):76–84. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X660814

Turalde CWR, Espiritu AI, Macinas IDN, et al (2021) Burnout among neurology residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional study. Neurol Sci 1–9

Sliwa JA, Clark GS, Chiodo A et al (2019) Burnout in diplomates of the american board of physical medicine and rehabilitation—prevalence and potential drivers: a prospective cross-sectional survey. PM & R 11(1):83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.07.013

Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L (2020) Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 77(5):387–401

Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L et al (2017) Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Burn Res 6:18–29

Wasson RS, Barratt C, O’Brien WH (2020) Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on self-compassion in health care professionals: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness 11(8):1914–1934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01342-5

Luberto CM, Shinday N, Song R et al (2018) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and prosocial behaviors. Mindfulness 9(3):708–724

Kirby JN, Tellegen CL, Steindl SR (2017) A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: current state of knowledge and future directions. Behav Ther 48(6):778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

MacBeth A, Gumley A (2012) Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 32(6):545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003

Sirois FM, Molnar DS, Hirsch JK (2015) Self-compassion, stress, and coping in the context of chronic illness. Self Identity 14(3):334–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.996249

Mistretta EG, Davis MC (2021) Meta-analysis of self-compassion interventions for pain and psychological symptoms among adults with chronic illness. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01766-7

Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC et al (2020) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synt 18(10):2119–2126

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W et al (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473

Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC et al (2021) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implement 19(1):3–10

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288

Simpson R, Mair FS, Mercer SW (2017) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis—a feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMC Neurol 17(1):94–94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0880-8

Dahmardeh HS, Afsaneh, Mohammadi E, Kazemnejad A (2020) Correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion in patients with multiple sclerosis—a cross-sectional study. Ceska a Slovenska Neurologie a Neurochirurgie 84(2):169–173. https://doi.org/10.48095/cccsnn2021169

Gedik Z, Idiman E (2020) Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Links to mental health, self-esteem, and self- compassion. Dusunen Adam. https://doi.org/10.14744/DAJPNS.2019.00061

Ignatova V (2016) Social Cognition Impairments in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Comparison with Imaging Studies, Disease Duration and Grade of Disability: IntechOpen

Nery-Hurwit M, Yun J, Ebbeck V (2018) Examining the roles of self-compassion and resilience on health-related quality of life for individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Disabil Health J 11(2):256–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.10.010

Pakenham KI, Cox S (2009) The dimensional structure of benefit finding in multiple sclerosis and relations with positive and negative adjustment: a longitudinal study. Psychol Health 24(4):373–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440701832592

Davidescu EI, Odajiu I, Tulbă D et al (2021) Characteristic personality traits of multiple sclerosis patients-an unicentric prospective observational cohort study. J Clin Med 10(24):5932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10245932

Giménez-Llort L, Martín-González JJ, Maurel S (2021) Secondary impacts of COVID-19 pandemic in fatigue, self-compassion, physical and mental health of people with multiple sclerosis and caregivers: the Teruel study. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091233 (published Online First: 2021/09/29)

Spitzer E, Pakenham KI (2018) Evaluation of a brief community-based mindfulness intervention for people with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Clin Psychol (Australian Psychological Society) 22(2):182–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12108

Chesi P, Marini MG, Mancardi GL et al (2020) Listening to the neurological teams for multiple sclerosis: the SMART project. Neurol Sci 41(8):2231–2240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04301-z

Lex H, Weisenbach S, Sloane J et al (2018) Social-emotional aspects of quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med 23(4):411–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1385818

Simpson R, Byrne S, Wood K et al (2018) Optimising mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn 14(2):154–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395317715504

Simpson R, Simpson S, Wood K et al (2019) Using normalisation process theory to understand barriers and facilitators to implementing mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn 15(4):306–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395318769354

Dahmardeh H, Sadooghiasl A, Mohammadi E et al (2021) The experiences of patients with multiple sclerosis of self-compassion: a qualitative content analysis. Biomedicine (Taipei) 11(4):35–42. https://doi.org/10.37796/2211-8039.1211

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Sedlmeier P, Eberth J, Schwarz M et al (2012) The psychological effects of meditation: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 138(6):1139

Strauss C, Lever Taylor B, Gu J et al (2016) What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin Psychol Rev 47:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

Senders A, Sando K, Wahbeh H et al (2016) Managing psychological stress in the multiple sclerosis medical visit: patient perspectives and unmet needs. J Health Psychol 21(8):1676–1687

Pétrin J, Donnelly C, McColl MA et al (2020) Is it worth it?: The experiences of persons with multiple sclerosis as they access health care to manage their condition. Health Expect 23(5):1269–1279. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13109

McCabe MP, Ebacioni KJ, Simmons R et al (2014) Unmet education, psychological and peer support needs of people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res 78(1):82–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.010

Artemiadis AK, Anagnostouli MC, Alexopoulos EC (2011) Stress as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis onset or relapse: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 36(2):109–120

Matza LS, Kim K, Phillips G et al (2019) Multiple sclerosis relapse: qualitative findings from clinician and patient interviews. Multiple Sclerosis Relat Disord 27:139–146

O’Loughlin E, Hourihan S, Chataway J et al (2017) The experience of transitioning from relapsing remitting to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: views of patients and health professionals. Disabil Rehabil 39(18):1821–1828

Malcomson K, Lowe-Strong A, Dunwoody L (2008) What can we learn from the personal insights of individuals living and coping with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil 30(9):662–674

Lakin L, Davis BE, Binns CC et al (2021) Comprehensive approach to management of multiple sclerosis: addressing invisible symptoms—a narrative review. Neurol Ther 10(1):75–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00239-2

Pucci E, Cartechini E, Taus C et al (2004) Why physicians need to look more closely at the use of complementary and alternative medicine by multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol 11(4):263–267

Rommer PS, König N, Sühnel A et al (2018) Coping behavior in multiple sclerosis—complementary and alternative medicine: a cross-sectional study. CNS Neurosci Ther 24(9):784–789

Shinto L, Yadav V, Morris C et al (2005) The perceived benefit and satisfaction from conventional and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in people with multiple sclerosis. Complement Ther Med 13(4):264–272

Sinclair S, Hack TF, Raffin-Bouchal S et al (2018) What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: a grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. BMJ Open 8(3):e019701

Sinclair S, Beamer K, Hack TF et al (2017) Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: a grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliat Med 31(5):437–447

McMillen JC, Fisher RH (1998) The Perceived Benefit Scales: measuring perceived positive life changes after negative events. Soc Work Res 22(3):173–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/22.3.173

Turalde CWR, Espiritu AI, Macinas IDN et al (2021) Burnout among neurology residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional study. Neurol Sci 43(3):1503–1511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05675-4

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD (2018) Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 283(6):516–529

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ et al (2016) Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 388(10057):2272–2281

Lamothe M, Rondeau É, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C et al (2015) Outcomes of MBSR or MBSR-based interventions in health care providers: a systematic review with a focus on empathy and emotional competencies. Complement Ther Med 24:19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.001

Braun SE, Kinser PA, Rybarczyk B (2019) Can mindfulness in health care professionals improve patient care? An integrative review and proposed model. Transl Behav Med 9(2):187–201

Sinclair S, Hack TF, Raffin-Bouchal S et al (2018) What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: a grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. BMJ Open 8(3):e019701-e19801. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019701

Sinclair S, Russell LB, Hack TF et al (2016) Measuring compassion in healthcare: a comprehensive and critical review. The Patient 10(4):389–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0209-5

Sinclair S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Venturato L et al (2017) Compassion fatigue: a meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud 69:9–24

Matos M, McEwan K, Kanovský M et al (2022) Compassion protects mental health and social safeness during the COVID-19 pandemic across 21 countries. Mindfulness 1–18

Costabile T, Carotenuto A, Lavorgna L et al (2021) COVID-19 pandemic and mental distress in multiple sclerosis: implications for clinical management. Eur J Neurol 28(10):3375–3383

Motolese F, Rossi M, Albergo G et al (2020) The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol 11:1255

Simpson R, Simpson S, Wasilewski M et al (2021) Mindfulness-based interventions for people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-aggregation of qualitative research studies. Disabil Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1964622

Cavalera C, Rovaris M, Mendozzi L et al (2018) Online meditation training for people with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Multi Scler J. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458518761187

Bogosian A, Chadwick P, Windgassen S et al (2015) Distress improves after mindfulness training for progressive MS: a pilot randomised trial. Multi Sclero J. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458515576261

Donald JN, Sahdra BK, Van Zanden B et al (2019) Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behaviour. Br J Psychol 110(1):101–125

Topcu G, Griffiths H, Bale C et al (2020) Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a meta-review of systematic reviews. Clin Psychol Rev 82:101923–102023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101923

Dennison L, McCloy Smith E, Bradbury K et al (2016) How do people with multiple sclerosis experience prognostic uncertainty and prognosis communication? A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 11(7):e0158982-e159082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158982

Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C et al (2006) Relationship between multimorbidity and health-related quality of life of patients in primary care. Qual Life Res 15(1):83–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-8661-z

Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C et al (2004) Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2(1):51–51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-51

Dennison L, Smith EM, Bradbury K et al (2016) How do people with multiple sclerosis experience prognostic uncertainty and prognosis communication? A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 11(7):e0158982

Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T (2009) A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev 29(2):141–153

Neff KD (2003) The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and identity 2(3):223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González J-MM et al (2005) Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol 4(9):556–566

Day JR, Anderson RA (2011) Compassion fatigue: an application of the concept to informal caregivers of family members with dementia. Nutr Res Pract 2011:408024. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/408024

Schumacher K, Beck CA, Marren JM (2006) FAMILY CAREGIVERS: caring for older adults, working with their families. Am J Nurs 106(8):40–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-200608000-00020

Croog SH, Burleson JA, Sudilovsky A et al (2006) Spouse caregivers of Alzheimer patients: problem responses to caregiver burden. Aging Ment Health 10(2):87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500492498

Taylor DH Jr, Ezell M, Kuchibhatla M et al (2008) Identifying trajectories of depressive symptoms for women caring for their husbands with dementia. J Am Geriatrics Soc (JAGS) 56(2):322–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01558.x

Papadopoulos I, Taylor G, Ali S et al (2017) Exploring nurses’ meaning and experiences of compassion: an international online survey involving 15 countries. J Transcult Nurs 28(3):286–295

Howick J, Steinkopf L, Ulyte A et al (2017) How empathic is your healthcare practitioner? A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient surveys. BMC Med Educ 17(1):136–236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0967-3

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simpson, R., Posa, S., Bruno, T. et al. Conceptualization, use, and outcomes associated with compassion in the care of people with multiple sclerosis: a scoping review. J Neurol 270, 1300–1322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11497-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11497-x