Abstract

Background

Many patients with several concurrent medical conditions (multimorbidity) are seen in the primary care setting. A thorough understanding of outcomes associated with multimorbidity would benefit primary care workers of all disciplines. The purpose of this systematic review was to clarify the relationship between the presence of multimorbidity and the quality of life (QOL) or health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients seen, or likely to be seen, in the primary care setting.

Methods

Medline and Embase electronic databases were screened using the following search terms for the reference period 1990 to 2003: multimorbidity, comorbidity, chronic disease, and their spelling variations, along with quality of life and health-related quality of life. Only descriptive studies relevant to primary care were selected.

Results

Of 753 articles screened, 108 were critically assessed for compliance with study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thirty of these studies were ultimately selected for this review, including 7 in which the relationship between multimorbidity or comorbidity and QOL or HRQOL was the main outcome measure. Major limitations of these studies include the lack of a uniform definition for multimorbidity or comorbidity and the absence of assessment of disease severity. The use of self-reported diagnoses may also be a weakness. The frequent exclusion of psychiatric diagnoses and presence of potential confounding variables are other limitations. Nonetheless, we did find an inverse relationship between the number of medical conditions and QOL related to physical domains. For social and psychological dimensions of QOL, some studies reveal a similar inverse relationship in patients with 4 or more diagnoses.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm the existence of an inverse relationship between multimorbidity or comorbidy and QOL. However, additional studies are needed to clarify this relationship, including the various dimensions of QOL affected. Those studies must employ a clear definition of multimorbidity or comorbidity and valid ways to measure these concepts in a primary care setting. Pursuit of this research will help to better understand the impact of chronic diseases on patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With technological advances and improvements in medical care and public health policy, an increasingly large number of patients survive medical conditions that used to be fatal. As a result of this phenomenon, and parallel to the aging of the population, a growing proportion of primary care patients presents with multiple coexisting medical conditions. From available data, it was estimated that 57 million Americans had multiple chronic conditions in 2000 and that this number will rise to 81 million by 2020 [1]. Epidemiological data from several countries support this estimate [2–8]. On average, patients aged 65 years and older present with 2.34 chronic medical conditions [7]. In fact, 50% of patients with a chronic disease have more than one condition [9].

The terms "comorbidity" and "multimorbidity" have been used to describe this phenomenon. Feinstein [10] originally described comorbidity as "any distinct additional entity that has existed or may occur during the clinical course of a patient who has the index disease under study." Kraemer [11] later referred to comorbidity in studying specific pairs of diseases. Van den Akker and colleagues [12] further refined both concepts, reserving the term "multimorbidity" to describe the co-occurrence of two or more chronic conditions; they also proposed some qualifiers to better classify the type of multimorbidity (simple, associative and causal). Unfortunately, much confusion still exists in the literature, where the 2 terms often seem to be used interchangeably. For the purpose of this paper, the term "multimorbidity" will be used according to Van den Akker and colleagues' definition and the focus will be solely on chronic diseases.

Previous reports on multimorbidity or comorbidity have documented that this phenomenon influences outcomes in many areas of health care [13–19]. Outcome measures that have been related to multimorbidity include mortality, length of hospital stay, and readmission. An association between disability and multimorbidity in elderly patients has also been described [14, 20–22].

Quality of life (QOL) is an outcome measure that is increasingly being used to evaluate outcomes in clinical studies of patients with chronic diseases [23–26]. QOL represents a subjective concept, with a multidimensional perspective encompassing physical, emotional, and social functioning [27]. It is important to address QOL as it has been associated with health and social outcomes [28] which may contribute to the worsening of the course of the diseases. In research and the medical literature, there is little distinction between health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and overall QOL (the latter encompasses not only health-related factors but also many non medical phenomena such as employment, family relationships, and spirituality) [29]. In practice, the terms are often used interchangeably. Different evaluation scales have been proposed to measure QOL or HRQOL. Some focus on a specific disease [30, 31], while others have wider applications (i.e., generic measurements) [32–34].

Little is known about the impact of multimorbidity on QOL of primary care patients [35], although this is where most patients receive their care. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review is to clarify the association between the presence of several concurrent medical conditions and the QOL or HRQOL of patients seen or likely to be seen in a primary care setting.

Methods

Data sources

For this review, we consulted Medline and Embase electronic databases for the reference period 1990 to 2003. Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy. Since the term "multimorbidity" does not have any equivalent in the thesaurus, databases were searched for the following terms: multimorbidity, comorbidity, and their spelling variations. The term "multimorbidity" was searched as a keyword, while "comorbidity" was searched as a Medical Subject Heading (MeSH). The term "chronic disease" was used to increase the sensitivity of the search. We also used the MeSH "quality of life" and the keyword "health-related quality of life" to help target pertinent literature.

To identify studies pertinent to the primary care setting, the following search terms were used: general practice, family practice, family medicine, family physician, and primary health care. A parallel strategy was used to identify all descriptive studies, regardless of the context of care, and the results were then combined. For the initial screening, the search was restricted to studies on human subjects, published in French or English. To be complete, we directly searched the Quality of Life Research and Health and Quality of Life Outcomes journals. We also screened references from key articles retrieved (hand searching).

Study selection

One researcher (LL) performed the initial screening. Any ambiguous findings were discussed with the lead investigator (MF) and a consensus was reached.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the purpose of this systematic review, we selected original, cross-sectional, and longitudinal descriptive studies that had evaluated the relationship between multimorbidity or comorbidity and QOL or HRQOL as the main outcome of interest. As stated earlier, we focused on the population of patients seen, or likely to be seen, in the primary care setting including members of the general population and residents of nursing homes and home healthcare facilities. We also selected original descriptive studies that had examined the relationship between multimorbidity or comorbidity and QOL or HRQOL as a secondary outcome.

Figure 1 shows our exclusion criteria. In keeping with our objectives, we did not include studies on specific diseases (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency disease) or populations unlikely to represent a large part of primary care practice. We also excluded any studies that did not address physical comorbidities, including those that exclusively examined mental disorders and associated mental comorbidities. Finally, we excluded studies in which the main outcome of interest was not QOL or HRQOL as well as those that used a nonstandard approach to measuring QOL or HRQOL.

Assessment of study quality

Before being included in the synthesis, the quality of each article selected was critically analyzed. For this assessment, we devised a scale in which points were assigned for study parameters indicative of good quality (e.g., well-defined populations, clear definitions, valid measures). Using this scale (Table 1), 2 researchers independently determined a global quality score for each article. The scores for each article were then compared and adjusted by consensus. To ensure adequate methodological quality, the cut-off score for an article to be included in the synthesis was 10 out of a maximum of 20 points.

Synthesis or results

Figure 1 shows the number of articles found at each stage of the selection process. Of the 753 articles screened, 108 were evaluated according to the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria. We also assessed the quality of each study before selecting 30 for inclusion in the synthesis: 7 that had evaluated the relationship between multimorbidity or comorbidity and QOL as the main outcome (Table 2) and 23, as a secondary outcome.

Quality of life as the main outcome measure

Of the 7 studies that featured QOL as a primary outcome [36–42], 5 had been conducted in European populations. We analyzed theses studies in detail. Quality scores for these studies ranged from 10 to 18 (out of a maximum of 20 points) and were highest in 2 studies from the Netherlands, one from the United States, and another study from Sweden. Table 2 presents a synthesis of the various studies.

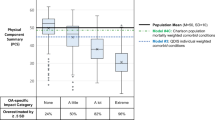

All studies came to the same conclusion, namely that there is an inverse relationship between the number of medical conditions and QOL or HRQOL. This association may be affected by the patient's age or gender. Whereas multimorbidity mostly affects physical dimensions of QOL or HRQOL [36, 37, 41], data from one study suggest that social and psychological dimensions may be affected in patients with 4 or more diagnoses [40].

In each study, investigators relied on simple count of chronic diseases from a limited list to measure multimorbidity. The chronic conditions included in this list varied among the studies, and no attempt was ever made to assess or account for the severity of each condition. Furthermore, 5 of the 7 studies did not consider psychiatric comorbidity, either because the illnesses considered did not include psychiatric diagnoses or because patients presenting with psychiatric diagnoses were excluded from the QOL evaluation. In most cases, the diagnostic information was obtained by a questionnaire that was completed by a nurse or a doctor or sometimes self-administered. One study assessed comorbidity via chart review.

To measure QOL, a variety of scales were used. Most studies (5/7) used tools from the Medical Outcomes Study i.e., the Short-Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) and Short-Form-20 Health Survey (SF-20). However, the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) was used in one study and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) was used in another. Although the number of domains explored varied from one study to the next, the measuring instruments used have excellent psychometric properties and validity.

The 4 studies associated with the highest quality scores explored only a limited number of potential confounders, namely age [37, 38], gender [36, 41], and socio-demographic and economic factors [38]. Effects of these confounders are reported in Table 2. The other 3 studies did not investigate potential confounders.

Quality of life as a secondary outcome measure

Of the 23 studies that evaluated the relationship between multimorbidity or comorbidity and QOL as a secondary outcome measure [43–65], most were done in Europe (9 studies) and the United States (12 studies). As with the main outcome studies, each used a simple count of a limited and varying number of chronic medical conditions to evaluate multimorbidity. While there was generally no attempt to assess or account for the severity of individual conditions, one study used a comorbidity index, the Duke Severity of Illness (DUSOI), for this purpose [48]. Diagnostic information was obtained from chart reviews and clinical evaluations (9 studies), from self-report questionnaires (13 studies), or both sources (1 study). Psychiatric comorbidity was evaluated in 13 studies.

As with the results from the main outcome studies, we found an inverse relationship between the number of medical conditions and the QOL relating to physical domains in all studies. However, the relationship between multimorbidity and QOL relating to psychological or social domains was less clear. Some investigators reported an effect of multimorbidity on these domains in patients with 3 or more diagnoses [54], while others reported no effect [48, 55].

As in the main outcome studies, tools from the Medical Outcomes Study, including the SF-36 (17 studies), SF-20 (3 studies), and Short-Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12) (1 study), were used to evaluate QOL in most of these studies. However, the NHP was used in one study and the Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB), in another. In the majority of studies, all of the QOL domains were explored.

Discussion

Although this systematic review confirms the inverse relationship between multimorbidity and QOL, it also raises some important questions. First, the relative lack of studies in primary care evaluating the association between multimorbidity and QOL or HRQOL is surprising given the number of patients who suffer from multiple concurrent chronic conditions. Although the existence of this association makes logical sense, it still has to be demonstrated and thoroughly studied to find ways of improving care for specially affected patients. Thus, the pressing question may not be whether there is an association but rather how strong is the association and what factors are responsible for it? Identifying these factors may contribute to better care for the affected patients. There is a clear need for further studies to address these issues.

Ultimately, multimorbidity has the potential to affect all domains of QOL. However, the influence of multimorbidity on the social and psychological dimensions of QOL is much less clear than its influence on the physical domains. It is noteworthy that several studies showed a significant decline in social and psychological dimensions of QOL in patients with 3, 4, or more concurrent diagnoses. What does this finding mean? Is there any bias that can explain this difference, or is it related to a certain capacity for adaptation? Are there other factors associated with this finding? All of these questions have yet to be answered.

All the studies examined were cross-sectional in nature. The effect of multimorbidity may vary over time. Some medical conditions may improve while others worsen resulting in various effects on QOL. Therefore, cross-sectional studies may not capture the real effect of multimobidity on QOL and predict the direction of change over time.

Defining and measuring multimorbidity

The absence of a uniform way of defining and measuring multimorbidity is of special concern and may explain some of the variability in our results. In most of the studies we evaluated, investigators had used only a simple list of diseases to identify concurrent medical conditions in patients, providing very incomplete information. Furthermore, the numbers and types of medical conditions in these lists varied among the studies, precluding comparisons.

Given the urgent need for conceptual clarity, Van den Akker and colleagues' definition of multimorbidity should be refined and advanced to achieve a common understanding. A distinction must be made between simple and complex chronic diseases. Treated hypothyroidism (simple) and ischemic heart disease (complex) obviously do not have the same impact on QOL. Moreover, the influence of single-organ versus multi-organ diseases needs to be appropriately weighed. Additional factors to be considered when defining multimorbidity include the severity of the conditions and the presence or absence of associated pain.

The use of self-reported diagnoses in many studies is another methodological limitation that may have introduced error. Patients may confuse symptoms and minor ailments with more significant disease states or may forget to report important diagnoses that are still active. Self-reporting may even be completely inaccurate in the presence of psychosomatic disorders. Conducting a chart review, clinical interview or using any specific standardized method may be a better way to obtain data related to diagnoses.

Another methodological limitation of most of the studies evaluated was their failure to consider the influence of psychiatric comorbidity. This was either because psychiatric diagnoses were not included in the lists of disease states or because patients presenting with psychiatric diagnoses were excluded from QOL assessment. Given the importance of psychiatric conditions in primary care practice with a prevalence of more than 20% [66], this limitation is simply unacceptable.

Confounders

QOL tends to decrease with age [67], whereas the number of diagnoses increases with age. Thus, it is appropriate to consider age as a potential confounding variable. The effect of age was explored in some of the studies that used QOL as a main outcome measure [37, 38, 41]. Reference to established norms would have facilitated interpretation of these results.

Only a few of the studies evaluated had explored the effect of gender. Furthermore, their results were contradictory, with gender being more detrimental to the QOL of women in some cases [41, 58] and men, in others [51].

Little has been reported about the effects of other potential confounding variables (e.g., socio-demographic and economic data, health habits, social support, number of drugs prescribed), although these factors are recognized as having an impact on QOL [68–71]. A few of the studies that used QOL as a secondary outcome measure considered the influence of socio-economic variables; however, their results were ambiguous, showing an impact in only about half of the studies. Some studies also demonstrated that, although socio-economic variables and health habits were significant predictors of QOL, the number of comorbidities was the strongest independent predictor of QOL [41, 56]. Only one study took into account social support, and this study revealed a relationship with the mental dimension of QOL [58]. Only one study took into account the number of drugs prescribed and found an impact on the physical domain of QOL [49]. This study looked specifically at comorbidities associated with arterial hypertension and their impact on QOL. Finally, other potential confounding variables such as marital status and living arrangements were considered in some studies, with demonstration of an impact on QOL in about half the studies.

Many other factors should be explored in this regard. For example, the presence of coexisting acute conditions, the time since the diagnosis of important chronic conditions, and the duration and prognosis of health problems are among factors that may explain some of the variability in QOL or HRQOL.

Research agenda

In light of the findings of this systematic review, further research is needed to clarify the relationship between multimorbidity and QOL. The early work will certainly be conceptual and theoretical. The resultant conceptual clarity would benefit both researchers and practitioners. How do we define and how should we measure multimorbidity are among the first questions to be addressed. More descriptive studies, which take into account the influence of multiple potential confounders, can then be conducted. Multivariate analyses will help control for the effects of these confounding variables. The effects of age and gender also need to be further explored, with reference to established norms. Although there is still a need for cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies are also needed to identify changes in the relationship between multimorbidity and QOL over time.

Study limitations

The main limitation of a systematic review is its inability to include all of the relevant literature. We realize that some articles may have been missed during the search stage. However, our review of a huge number of abstracts generated by different strategies improved the sensitivity of the search. Obviously, the absence of a keyword for multimorbidity is a limitation. However, we found that in the majority of cases in which the term "multimorbidity" was used to search, the term "comorbidity" also appeared in the list of keywords. Adding the term "chronic disease" also helped to circumvent the problem. Restricting the search to articles published in French or English is another limitation.

Conclusion

This systematic review focused on the relationship between the presence of several chronic coexisting medical conditions and QOL or HRQOL in a primary care setting. However, the studies evaluated had important limitations due to the lack of a uniform definition for multimorbidity or comorbidity, the absence of assessment of disease severity, the use of self-reported diagnoses, and the frequent exclusion of psychiatric diagnoses. The potential impact of important confounding variables was also neglected. In light of these observations, it seems clear that further studies are needed to clarify the impact of multimorbidity on QOL or HRQOL and its various dimensions (i.e., physical, social and psychological). A clear understanding of this relationship will ultimately help both researchers and primary health care professionals to deliver more comprehensive care.

Author contributions

MF was responsible for the conception and design of this systematic review and was also involved in the literature review. In addition, he was responsible for critically assessing the evaluated articles and drafting this manuscript. He takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and provided final approval of this version of the manuscript.

LL provided a major contribution to the literature review and critical appraisal of the identified articles. She also participated in the drafting of this manuscript and gave final approval of this version.

CH participated in both the conception and design of this review. She also contributed by critically revising this manuscript and gave final approval of this version.

AV participated in the design of this review. He also made an important contribution in critically revising the manuscript and gave final approval of this version.

ALN participated in the drafting of the manuscript and made an important contribution by critically revising it. He also gave final approval of this version.

DM participated in the drafting of the manuscript and made an important contribution by critically revising it. She also gave final approval of this version.

References

Wu SY, Green A: Projection of chronic illness prevalence and cost inflation Washington, DC: RAND Health 2000.

Daveluy C, Pica L, Audet N, Courtemanche R, Lapointe F: Enquête sociale et de santé 2 Edition Québec: Institut de la statistique du Québec 2000.

Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Lapointe L: Prévalence de la multimorbidité en médecine de première ligne. Affiche présentée à l'Association scientifique annuelle du Collège québécois des médecins de famille Québec, Canada 27 et 28 novembre 2003

Akker M vd, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA: Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 1998, 51: 367–375. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00306-5

Knottnerus JA, Metsemakers JFM, Höppener O, Limonard CBG: Chronicillness in the community and the concept of "social prevalence". Fam Pract 1992, 9: 15–21.

Schellevis FG, Velden J vd, Lisdonk E vd, Eijk JThM v, Weel C v: Comorbidity of chronic diseases in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46: 469–473. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90024-U

Metsemakers JFM, Höppener O, Knottnerus JA, Kocken RJJ, Limonard CBG: Computerized health information in the Netherlands: a registration network of family practices. Br J Gen Pract 1992, 42: 102–106.

Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G: Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002, 162: 2269–2276. 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269

Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung HY: Persons with chronic conditions: their prevalence and costs. JAMA 1996, 276: 1473–1479. 10.1001/jama.276.18.1473

Feinstein AR: The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease. J Chron Dis 1970, 23: 455–469. 10.1016/0021-9681(70)90054-8

Kraemer HC: Statistical issues in assessing comorbidity. Stat Med 1995, 14: 721–723.

Akker M vd, Buntinx F, Knottnerus A: Comorbidity or multimorbidity: what's in a name? A review of literature. Eur J Gen Pract 1996, 2: 65–70.

West DW, Satariano WA, Ragland DR, Hiatt RA: Comorbidity and breast cancer survival: a comparison between black and white women. Ann Epidemiol 1996, 6: 413–419. 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00096-8

Extermann M, Overcash J, Lyman GH, Parr J, Balducci L: Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1998, 16: 1582–1587.

Greenfield S, Apolone G, McNeil BJ, Cleary PD: The importance of co-existent disease in the occurrence of postoperative complications and one-year recovery in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Comorbidity and outcomes after hip replacement. Med Care 1993, 31: 141–154.

Librero J, Peiro S, Ordinana R: Chronic comorbidity and outcomes of hospital care: length of stay, mortality, and readmission at 30 and 365 days. J Clin Epidemiol 1999, 52: 171–179. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00160-7

Incalzi RA, Capparella O, Gemma A, Landi F, Bruno E, Di Meo F, Carbonin P: The interaction between age and comorbidity contributes to predicting the mortality of geriatric patients in the acute-care hospital. J Intern Med 1997, 242: 291–298. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00132.x

Poses RM, McClish DK, Smith WR, Bekes C, Scott WE: Prediction of survival of critically ill patients by admission comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol 1996, 49: 743–747. 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00021-2

Rochon PA, Katz JN, Morrow LA, McGlinchey-Berroth R, Ahlquist MM, Sarkarati M, Minaker KL: Comorbid illness is associated with survival and length of hospital stay in patients with chronic disability. A prospective comparison of three comorbidity indices. Med Care 1996, 34: 1093–1101. 10.1097/00005650-199611000-00004

Guralnik JM, LaCroix AZ, Evertt DF: Aging in the eighties: the prevalence of co-morbidity and its association with disability Washington, DC: DHHS (NCHS) 1989.

Mulrow CD, Gerety MB, Cornell JF, Lawrence VA, Kanten DN: The relationship between disease and function in very frail elders. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994, 42: 374–380.

Fuchs Z, Blumstein T, Novikov I, Walter-Ginzburg A, Lyanders M, Gindin J, Habot B, Modan B: Morbidity, comorbidity, and their association with disability among community-dwelling oldest in Israel. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1998, 53: M447-M455.

Fan VS, Curtis JR, Tu S-P, McDonell M, Fihn SD: Using quality of life to predict hospitalization and mortality in patients with obstructive lung diseases. CHEST 2002, 122: 429–436. 10.1378/chest.122.2.429

Howes CJ, Reid Carrington M, Brandt C, Ruo B, Yerkey MW, Prasad B, Lin C, Peduzzi P, Ezekowitz MD: Exercise tolerance and quality of life in elderly patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2001, 6: 23–29.

Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, Propert KJ, Alexander RB, Litwin MS, Nickel JC, O'Leary MP, Nadler RP, Pontari MA, Shoskes DA, Zeillin SI, Fowler JE, Mazurick CA, Kishel L, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, The Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network Group: Demographic and clinical characteristics of men with chronic prostatitis: The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort Study. J Urol 2002, 168: 593–598. 10.1097/00005392-200208000-00040

Xuan J, Kirchdoerfer LJ, Boyer JG, Norwood GJ: Effects of comorbidity on health-related quality-of-life score: an analysis of clinical trial data. Clin Ther 1999, 21: 383–403. 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88295-8

McDowell , Newell C: Measuring Health, a guide to rating scales and questionnaires 2 Edition New York: Oxford University Press 1996.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD: SF-36 physical and mental health summary scores: a user's manual Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center 1994.

Gill T, Feinstein AR: A critical appraisal of the quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 1994, 272: 619–626. 10.1001/jama.272.8.619

DCCT Research Group: Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality of life measure for the diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT). Diabetes Care 1998, 11: 725–732.

Meenan RF, Gertman PM, Mason JH: Measuring health status in arthritis: the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales. Arthritis Rheum 1980, 23: 146–152.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30: 473–483.

Hunt SM, McEwen J: The development of a subjective health indicator. Sociol Health Illness 1980, 2: 231–246. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11340686

Bergner M, Robbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS: The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care 1981, 19: 787–805.

Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A: Multimorbidity in the medical literature:A bibliometric study. Can Fam Physician 2004, in press.

Cheng L, Cumber L, Dumas C, Winter R, Nguyen KM, Nieman LZ: Health related quality of life in pregeriatric patients with chronic diseases at urban, public supported clinics. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2003, 1: 63. 10.1186/1477-7525-1-63

Wensing M, Vingerhoets E, Grol R: Functional status, health problems, age and comorbidity in primary care patients. Qual Life Res 2001, 10: 141–148. 10.1023/A:1016705615207

Michelson H, Bolund C, Brandberg Y: Multiple chronic health problems are negatively associated with health related quality of life (HRQOL) irrespective of age. Qual Life Res 2000, 9: 1093–1104. 10.1023/A:1016654621784

Cuijpers P, van Lammeren P, Duzijn B: Relation between quality of life and chronic illnesses in elderly living in residential homes: a prospective study. Int Psychogeriatr 1999, 11: 445–454. 10.1017/S1041610299006067

Grimby A, Svanborg A: Morbidity and health-related quality of life among ambulant elderly citizens. Aging (Milano) 1997, 9: 356–364.

Kempen GI, Jelicik M, Ormel J: Personality, chronic medical morbidity and health-related quality of life among older persons. Health Psychol 1997, 16: 539–546. 10.1037//0278-6133.16.6.539

Fryback DG, Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BE, Dorn N, Peterson K, Martin PA: The Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study: initial catalog of health-state quality factors. Med Decis Making 1993, 13: 89–102.

Glasgow RE, Ruggiero L, Eakin EG, Dryfoos J, Chobanian L: Quality of life and associated characteristic in a large national sample of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 1997, 20: 562–567.

Talamo J, Frater A, Gallivan S, Young A: Use of the short form 36. SF 36) for health status measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rhumatol 1997, 36: 463–469. 10.1093/rheumatology/36.4.463

Kempen GI, Ormel J, Brilman EI, Relyveld J: Adaptive responses among Dutch elderly: the impact of eight chronic medical conditions on health-related quality of life. Am J Public Health 1997, 87: 38–44.

Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Juang KD: Quality of life differs among headache diagnoses: analysis of SF-36 survey in 901 headache patients. Pain 2001, 89: 285–292. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00380-8

Katz DA, McHorney CA, Atkinson RL: Impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Gen Intern Med 2000, 15: 789–796. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.90906.x

Berardi D, Berti Ceroni G, Leggieri G, Rucci P, Ustun B, Ferrari G: Mental, physical and functional status in primary care attenders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1999, 29: 133–148.

Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Stevens P, Krediet RT: Quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: self-assessment 3 months after the start of treatment. The Necosad Study Group. Am J Kidney Dis 1997, 29: 584–592.

Ferrer M, Alonso J, Morera J, Marrades RM, Khalaf A, Aguar MC, Plaza V, Prieto L, Antó JM: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. The Quality of Life of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1997, 127: 1072–1079.

Kusek JW, Greene P, Wang SR, Beck G, West D, Jamerson K, Agodoa LY, Faulbrer M, Level B: Cross-sectional study of health-related quality of life in African Americans with chronic renal insufficiency: the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2002, 39: 513–524.

Sprangers MA, de Regt EB, Andries F, van Agt HM, Bijl RV, de Boer JB, Foets M, Hoeymans N, Jacobs AE, Kempen GI, Miedema HS, Tijhuis MA, de Haes HC: Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol 2000, 53: 895–907. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00204-3

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells K, Rogers WH, Berry SD, McGlynn EA, Ware JH: Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989, 262: 907–913. 10.1001/jama.262.7.907

Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL: Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res 2000, 8: 160–170.

Small GW, Birkett M, Meyers BS, Koran LM, Bystritsky A, Nemeroff CB: Impact of physical illness on quality of life and antidepressant response in geriatric major depression. Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996, 44: 1220–1225.

Katz DA, McHorney CA: The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Fam Pract 2002, 51: 229–235.

Erickson SR, Christian RD Jr, Kirking DM, Halman LJ: Relationship between patient and disease characteristics, and health-related quality of life in adults with asthma. Respir Med 2002, 96: 450–460. 10.1053/rmed.2001.1274

Van Manen JG, Bindels PJE, Dekker FW, Ijzermans CJ, Bottema BJ, van der Zee JS, Schade E: Added value of co-morbidity in predicting health-related quality of life in COPD patients. Respir Med 2001, 95: 496–504. 10.1053/rmed.2001.1077

Van Manen JG, Bindels PJE, Dekker FW, Bottema BJ, van der Zee JS, Ijzermans CJ, Schadé E: The influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol 2003, 56: 1177–1184. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00208-7

Sapp AL, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Hampton JM, Moinpour CM, Remington PL: Social networks and quality of life among female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer 2003, 98: 1749–1758. 10.1002/cncr.11717

Stein MB, Barrett-Connor E: Quality of life in older adults receiving medications for anxiety, depression, or insomnia: Findings from a community-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002, 10: 568–574. 10.1176/appi.ajgp.10.5.568

Osterhaus JT, Townsend RJ, Gandek B, Ware JE Jr: Measuring the functional status and well-being of patients with migraine headache. Headache 1994, 34: 337–343.

Sturm R, Wells KB: Does obesity contribute as much to morbidity as poverty or smoking? Public Health 2001, 115: 229–235. 10.1016/S0033-3506(01)00449-8

Lam CLK: Reliability and construct validity of the Chinese (Hong Kong) SF-36 patients in primary care. Hong Kong Practitioner 2003, 25: 468–475.

Vacek PM, Winstead-Fry P, Secker-Walker RH, Hooper GJ: Factors influencing quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 2003, 12: 527–537. 10.1023/A:1025098108717

Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun B, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T: Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA 1994, 272: 1741–1748. 10.1001/jama.272.22.1741

Leplège A, Ecosse E, Pouchot J, Coste J, Perneger T: Le questionnaire MOS SF-36. Manuel de l'utilisateur et guide d'interprétation des scores Paris: Estem 2001.

Parker PA, Baile WF, De Moor C, Cohen L: Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology 2003, 12: 183–193. 10.1002/pon.635

Brzyski RG, Medrano MA, Hyatt-Santos JM, Ross JS: Quality of life in low-outcome menopausal women attending primary care clinics. Fertil Steril 2001, 76: 44–50. 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)01852-0

Fincke BG, Miller DR, Spiro A: The interaction of patient perception of overmedication with drug compliance and side effects. J Gen Intern Med 1998, 13: 182–185. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00053.x

Lawrence WF, Fryback DG, Martin PA, Klein R, Klein BE: Health status and hypertension: a population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol 1996, 49: 1239–1245. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00220-X

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by grants from Pfizer Canada and the Family Medicine Department at the University of Sherbrooke.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Fortin, M., Lapointe, L., Hudon, C. et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2, 51 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-51

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-51