Abstract

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a combination of motor and non-motor dysfunction. Dysphagia is a common symptom in PD, though it is still too frequently underdiagnosed. Consensus is lacking on screening, diagnosis, and prognosis of dysphagia in PD.

Objective

To systematically review the literature and to define consensus statements on the screening and the diagnosis of dysphagia in PD, as well as on the impact of dysphagia on the prognosis and quality of life (QoL) of PD patients.

Methods

A multinational group of experts in the field of neurogenic dysphagia and/or PD conducted a systematic revision of the literature published since January 1990 to February 2021 and reported the results according to PRISMA guidelines. The output of the research was then analyzed and discussed in a consensus conference convened in Pavia, Italy, where the consensus statements were drafted. The final version of statements was subsequently achieved by e-mail consensus.

Results

Eighty-five papers were used to inform the Panel’s statements even though most of them were of Class IV quality. The statements tackled four main areas: (1) screening of dysphagia: timing and tools; (2) diagnosis of dysphagia: clinical and instrumental detection, severity assessment; (3) dysphagia and QoL: impact and assessment; (4) prognostic value of dysphagia; impact on the outcome and role of associated conditions.

Conclusions

The statements elaborated by the Consensus Panel provide a framework to guide the neurologist in the timely detection and accurate diagnosis of dysphagia in PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder worldwide [1]. The prevalence of PD is estimated at 6.1 million individuals globally and will likely increase worldwide with increased life expectancy [2]. PD is characterized by motor features such as tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia, and several non-motor features such as dysphagia, autonomic dysfunction, sleep disorders, cognitive impairment, depression, and psychosis that may occur at any time during the disease course, but become more frequent with advanced disease [3, 4].

Dysphagia in PD is a manifestation of swallowing dysfunction that may involve oral, pharyngeal or esophageal phases of swallowing and may be present in every stage of the disease [5]. Indeed, even though swallowing disorders become apparent mostly in the advanced stage of PD, they may already be present in the early stages, when they often go undetected [5]. Dysphagia frequently worsens with disease progression and may vary with motor fluctuations [6,7,8]. Globally, the prevalence of dysphagia in PD is estimated between 40 and 80% depending on type of assessment performed [7].

Dysphagia can negatively affect the quality of life (QoL) of individuals because of the progressive difficulty of oral intake (food, drinks or oral medication), weight loss, dehydration, malnutrition and limitation of social activities [9]. Moreover, aspiration pneumonia due to swallowing dysfunction is an important and common cause of hospitalization in patients with PD [10, 11], resulting in severe complications and even death [12,13,14].

To date, there is no generally accepted approach to the screening and the diagnosis of dysphagia in PD. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify standardized protocols for the clinical assessment and investigation of dysphagia in this population. Moreover, it is important to emphasize the need for the early identification of swallowing abnormalities in patients with PD, especially as initially they may be asymptomatic [6].

An established and formal methodology to provide reliable guidance in complex health issues in the absence of high-quality evidence is represented by a consensus-based process. In this process, expert professionals reach a consensus on statements aimed at providing a guide for clinical practice on the basis of the best available evidence and the group’s expertise. Typically, a panel of experts, after examining the relevant scientific information and discussing the clinical issues, produce statements that reflect their shared views, in agreement with available evidence [15].

To increase the awareness of dysphagia in PD in the neurological health care practice and to optimize its screening and diagnosis, a group of experts in the field of dysphagia and/or PD set forth a Multinational Consensus Conference (MCC) with the following objectives:

-

(1)

To define the appropriate timing for screening dysphagia in patients with PD and to identify reliable modalities;

-

(2)

To define appropriate investigations for detecting swallowing alterations in PD and to assess their severity;

-

(3)

To assess the impact of dysphagia on the QoL of patients;

-

(4)

To assess the prognostic values of dysphagia in PD outcome;

-

(5)

To identify unmet needs and highlight areas for future research.

Methods

The project was initiated by the Organizing Committee during the 2018 edition of the ‘Dysphagia Update’ Meeting, an international scientific event focused on neurogenic dysphagia that has been held biannually since 2008 under the patronage of the Italian Society of Neurology, the Italian Society of Neurorehabilitation, and the European Society for Swallowing Disorders. The MCC method was designed according to the US National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program (http://consensus.nih.gov) [16] and the Methodological Handbook of the Italian National Guideline System [17].

The project was developed over a period of 36 months following five steps: (1) assignment phase, (2) scoping phase, (3) assessment phase, (4) face-to-face MCC, held on 27–28th September 2019, at the IRCCS Mondino Foundation, and finally (5) update of the evidence (up to February 2021) and refinement of statements by e-mail.

The core of the consensus panel was formed by Italian neurologists who met regularly at the ‘Dysphagia Update’ meetings. Additional specialists, also from different medical disciplines and from other Countries were invited to achieve a broad geographic and multidisciplinary representation. Participants were selected based on their recognized involvement in the care of large cohorts of PD patients and/or their involvement in research projects on PD and/or neurogenic dysphagia, and/or because of their publication record on neurogenic dysphagia in peer-reviewed journals. Participants were invited by e-mail. A single reminder was sent to those who did not reply to the first invitation. The final group was formed by 21 neurologists, 4 ENT specialists, three phoniatricians, two gastroenterologists, 4 speech-language pathologists, 2 clinical nutritionists, one radiologist and a statistician.

In the assignment phase, four working teams with specific roles were identified:

-

1.

The Scientific Committee, comprising seven members, planned and organized the whole project and developed the questions following the Classification of Evidence Schemes of the Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual of the American Academy of Neurology [18]. Several clinically relevant questions were proposed by the Scientific Committee and discussed during several iterations according to the PICO format as stated in Appendix 1. The selection of the final questions to be answered in this review was also guided by the results of a preliminary literature search conducted to evaluate whether there was available evidence to support the answers. The selection of the clinical questions was ultimately driven by the following criteria: i) to identify clinically relevant, focused topics (not taking too narrow a focus nor too broad), ii) to select questions that could be answered, at least partly, on the basis of published, peer-reviewed evidence.

-

2.

The Technical Committee, formed by six members, systematically reviewed the evidence, organized the results into tables, and assisted the other teams in all steps of the project;

-

3.

A working group (WG) formed by nine members whose tasks were: 1) to prepare the first draft of answers to the proposed questions prior to the consensus conference and 2) to point out the research gaps in current knowledge and to propose areas for future research;

-

4.

The consensus development panel, comprising six members, was responsible for defining the presentation procedures at the MCC and for the assessment of the final statements.

In the scoping phase, the details of the literature review necessary to answer the questions developed by the Scientific Committee (Appendix 1) were defined, together with protocol for the conference. In the assessment phase, the Technical Committee carried out a systematic review of the literature, which was reported according to PRISMA guidelines [19]. Studies eligible for inclusion were those reporting original data on patients with PD suffering from dysphagia on screening, diagnosis, prognosis and QoL, regardless of the design type, published since January 1990. The following types of studies were excluded: studies published in abstract form only, case reports, reviews, editorials, letters, studies on animals, and studies including patients with dysphagia of mixed etiology where data regarding PD could not be clearly enucleated. Published studies were identified from the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE database, by means of specific search strategies, using a combination of exploded MeSH terms and free text (search strategy is reported in Appendix 2). Reference lists of identified articles were reviewed to find additional references. All abstracts or full papers without electronic abstracts were reviewed independently by two reviewers to identify potentially relevant studies. Disagreement was resolved by discussion. Each study was classified according to various descriptors, including topic domain, sample size, design, and level of evidence according to the Classification of Evidence Schemes of the Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual of the American Academy of Neurology [18].

Each study was graded according to its risk of bias from Class I (highest quality) to Class IV (lowest quality). Risk of bias was judged by assessing specific quality elements (i.e., study design, patient spectrum, data collection, masking) for each clinical topic (screening, diagnosis, prognosis, treatment). This classification was performed by two reviewers, with disagreement resolved by discussion.

In consideration of the multidisciplinary of the expert groups and the generally weak strength of evidence emerged from the systematic analysis of the literature, we adopted the modified Delphi method [18] to achieve consensus and develop the final statements. The method consisted in four subsequent rounds. The first one was performed electronically: a first set of statements were generated and sent by e-mail to the experts of the WG. Answers were collected and analyzed to inform necessary changes. The second and the third rounds were carried out face-to-face, during the first and the second day of the MCC, respectively, with the participation of the entire panel. The fourth round was performed electronically: the final version of the statements, adapted, when required, according to the additional analysis of paper published since the consensus conference, was circulated by e-mail to the experts. On every round, a minimum of 80% agreement for each statement was required for inclusion in the final consensus statement (25/31).

Ultimately, the systematic literature analysis covered the period from January 1990 to February 2021.

Results

Questions of the consensus conference

The Scientific Committee formulated and submitted three questions each on the screening and the diagnosis of dysphagia in PD and two questions each on the QoL and the prognosis of patients with PD and dysphagia.

Questions on screening:

-

a)

When is it indicated to screen for dysphagia in patients with PD?

-

b)

When should dysphagia be suspected in patients with PD?

-

c)

What clinical tools should be used to screen for dysphagia in patients with PD?

Questions on diagnosis:

-

a)

What clinical tools should be used to detect the presence of dysphagia?

-

b)

What instrumental investigations should be used to detect the presence of dysphagia?

-

c)

How should severity of dysphagia be assessed?

Questions on QoL:

-

a)

What is the effect of dysphagia on the QoL of patients with PD?

-

b)

How should dysphagia-related QoL in patients with PD be clinically assessed?

Questions on prognosis:

-

a)

Does dysphagia influence the prognosis of PD?

-

b)

What factors or associated conditions can influence the prognosis of dysphagia in PD?

For each question, specific eliciting questions were formulated by the Technical Committee to stimulate and guide the discussion among the members of the WG (Supplementary material 1).

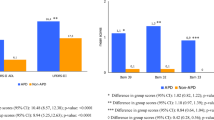

Systematic review

The literature search retrieved 747 citations from electronic search and 8 records from manual search in the reference lists (Fig. 1). The abstract of the 747 citations were reviewed to assess potential relevance, and 249 were included for full text evaluation. A total of 174 papers finally met the prespecified inclusion criteria. Of these, 117 papers dealt with the questions posed, but only 85 contained useful findings to elaborate the statements. The majority of studies were of Class IV quality. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the studies retrieved (see Supplementary material 2 for complete list of references), whereas Table 2 depicts the main information on the single studies used as the basis for the statements.

Screening of dysphagia in PD

Although dysphagia is a common symptom in PD, most patients with PD do not complain of swallowing difficulties even when specifically asked, because they are generally not aware of their swallowing problems [20, 21].

Therefore, there is a gap in the literature on dysphagia prevalence between subjectively reported impairment (35%) and objectively confirmed swallowing impairments by screening questionnaires or clinical evaluations (85%) [7, 22]. Indeed, signs of penetration and/or aspiration may be detected in 20% of the PD population without any complaint of swallowing difficulties [23, 24].

The early diagnosis of dysphagia in PD may be challenging. However, many symptoms and signs may indicate the need for a screening. These are: increased duration of meals, difficulty in tablet swallowing and sensation of food sticking or persisting in the throat after swallowing, coughing and choking during ingestion of food and liquids, post-swallowing changes in voice (e.g. gurgling voice), weight loss or low body mass index while recurrent chest infections [25,26,27,28,29]. Also, drooling is considered by some authors as a possible indirect marker of dysphagia, since it can be the consequence of oropharyngeal swallowing alterations [30]. Using a modified barium swallowing videofluoroscopy, Nóbrega et al. [30] showed that all patients with PD and drooling also presented changes in the oral phase of swallowing, whereas alterations in the pharyngeal phase were detected in 94% of subjects. Drooling also correlates with dysphagia severity and may have a negative prognostic value, as it is associated with an increased risk of salivary aspiration without any outward sign of coughing, choking, or respiratory change (silent aspiration) [30,31,32].

A recent study [33] conducted in patients with PD aged > 63.5 years identified the following characteristics as predictors of an increased risk to develop dysphagia: a daily levodopa equivalent dose higher than 475 mg and a PD clinical subtype characterized by early postural instability and gait difficulty.

Altogether, the data from the literature suggest that dysphagia in PD should be suspected in the presence of direct symptoms (coughing or choking when eating or drinking, wet-sounding voice when eating or drinking, sensation of food stuck in the throat and difficulty of chewing food properly), or indirect signs (congestion of the lower respiratory tract, bronchitis or pneumonia and unintentional weight loss).

In these cases, a screening evaluation should be completed regardless of PD disease stage [5, 34].

The presence of different symptoms and/or signs in combination can increase the sensitivity and specificity of the screening procedures [35, 36].

Different clinical scales and questionnaires have been proposed for screening dysphagia in neurodegenerative diseases [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], though there is no agreement on the best algorithm for evaluating patients with PD.

The following clinical scale and questionnaires (evidence of class III and IV) may be used for screening of dysphagia in PD:

-

Swallowing disturbance questionnaire (SDQ) [38]: a self-reported questionnaire containing 15 items on swallowing disturbances. It is considered a validated tool to detect early dysphagia in patients with PD. It has a good sensitivity and specificity (80.5 and 81.3%, respectively).

-

Munich Dysphagia test-Parkinson’s disease (MDT-PD) [39]: a self-reported questionnaire useful to screen for initial oropharyngeal symptoms and the risk of laryngeal penetration and/or aspiration in PD. It consists of 26 items divided into 4 categories. The MDT-PD is considered a sensitive and specific questionnaire; however, it was reported that compared with FEES it has a low sensitivity in detecting aspiration, though maintaining good specificity [46].

-

Swallowing Clinical Assessment Score in Parkinson’s disease (SCAS-PD): a quantitative clinical scale consisting of 12 items designed to detect alterations in the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing in PD [36]. Branco et al. [40] validated this scale using the videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) as the reference diagnostic test. They showed that SCAS-PD has a high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (87.5%) and it enables to detect clinical signs of aspiration with a good concordance with the gold standard VFSS (weighted kappa concordance rate of 0.71).

-

Radboud Oral Motor Inventory for Parkinson’s disease (ROMP) [41]: a questionnaire developed to assess three main domains: speech, swallowing, and saliva control. This scale represents a valid tool to identify swallowing difficulties in PD, though it contains a limited number of items.

-

Handheld Cough Testing (HCT), a novel tool for cough assessment and dysphagia screening in PD. The HCT is able to identify differences in cough airflow during reflex and voluntary cough tasks, and screen for people with dysphagia in PD with high sensitivity and specificity (90.9% sensitivity; 80.0% specificity)[47].

Although these screening tools look promising for an early diagnosis of dysphagia in patients with PD, they are not cross-culturally validated. Therefore, there is an unmet need to translate, adapt, and cross-culturally validate screening measures.

Diagnosis of dysphagia in PD

The clinical swallowing examination has a higher sensitivity to identify swallowing abnormalities compared to screening questionnaires [6, 24]. Thus, it is indicated in all patients with a positive screening test result. The clinical swallowing examination is performed preferably by a speech-language pathologist and includes a patient/caregiver interview, evaluation of cognition and communication abilities, oral motor assessment, and swallowing trials. For those centres who do not have a speech-language therapist with an expertise in the evaluation of neurogenic dysphagia, a referral pathway should be put in place.

The Water Swallow Test (WST) is among the most common tools used during clinical swallowing examination because of its rapidity and ease of use. The WST may detect dysphagia early in PD [48] and identify subjects at risk of aspiration [49]. However, it may underestimate the incidence of oropharyngeal dysphagia, since its diagnostic accuracy depends on the preservation of the cough reflex and pharyngo-laryngeal sensitivity. Therefore, the combination of the WST with clinical tests assessing voluntary and/or reflex cough function increases the positive and negative predictive value of the clinical swallowing assessment [50, 51].

In addition to the above, cough testing can be useful for assessing severity of dysphagia and aspiration risk [27, 52]. In particular, compared to voluntary cough testing, reflexive cough testing can be more sensitive in distinguishing between patients with PD with mild (PAS 3–5) or severe dysphagia (PAS 6–8), as well as between patients with penetration above (PAS 2–3) or below (PAS 4–8) the level of the vocal folds [27].

Two studies have shown that reduced tongue pressure and motility are among other possible indicators of early dysphagia in PD [42, 53].

Several instrumental investigations detect swallowing abnormalities with higher sensitivity than the clinical swallowing examination. Swallowing abnormalities of swallow have been observed in almost all patients using different diagnostic techniques, even in the early stages of disease in studies performed by different groups [23, 24, 54,55,56,57,58,59]. There is no consensus on whether these investigations should be carried out in all patients with PD regardless of the presence of signs and symptoms associated with dysphagia. This represented one of the main subjects of debate during the MCC. On one hand, when considering that silent aspiration may go undetected by clinical evaluation and it may be present even in the early stages of the disease, it seems reasonable to apply instrumental investigations also in subjects with clinically safe and functional swallowing, [5, 20, 58]. On the other hand, it seems important to consider that some instrumental diagnostic investigations for dysphagia are not widely available. Thus, the prevailing view was to consider mandatory such evaluation only in patients with clinical signs of dysphagia (see statement below).

Several studies have evaluated the role of different investigation methods in the diagnosis of dysphagia in PD. VFSS and FEES should be used as a first approach, as they enable detection of aspiration, penetration, and residue with similar high sensitivity and specificity [60]. VFSS directly reveals penetration/aspiration [61,62,63], also providing useful information when the oral and/or esophageal phase is impaired [64,65,66,67,68]. FEES ensures an appropriate assessment of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing and the detection of penetration/aspiration phenomena, both directly (before or after the swallow, i.e. in case of premature spillage and residue, respectively) and indirectly [5, 31, 69,70,71]. FEES has the advantage over VFSS of being easier to perform, even at the patient’s bedside, and allows to test swallowing of real food and to assess secretion management. Moreover, as FEES does not require the use of radiation, it can be repeated even at short time intervals, thus allowing accurate follow-ups.

Oro-Pharyngo-Esophageal Scintigraphy (OPES) is a useful tool for the early detection of dysphagia [72], but its diagnostic role in PD remains to be ascertained as only a single study has been carried out in this patient population [73]. Although only preliminary evidence is available, swallowing evaluation with high-resolution manometry (HRM) represents another interesting diagnostic tool, capable to show subtle swallowing changes in the early stages of PD even in the absence of swallowing changes on VFSS [57, 74].

The Electro-Kinesiologic Swallowing Study (EKSS) represents an additional useful diagnostic tool to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms of oropharyngeal dysphagia and provide clues for treatment selection [56, 75,76,77]. For example, electromyography of the cricopharyngeal muscle (i.e., the main component of the upper esophageal sphincter, UES) helps to clarify whether failure in UES opening during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing is due to persistent sphincter hyperactivity or to reduced elevation of the pharyngeal-laryngeal structures [78, 79]. In the former case, botulinum toxin injection into the cricopharyngeal muscle may be beneficial [78, 79]. However, very few centers use UES electromyography routinely, thus this examination cannot currently be considered as a standard test for dysphagia.

Gastroenterological investigations including esophageal manometry, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, acid- and reflux-related tests, and/or radiological investigations such as barium swallow should always be carried out in the presence of esophageal symptoms (e.g. dysphagia for solid foods, regurgitation, food sticking after swallowing) and/or when oropharyngeal evaluations detect findings suggestive of structural or functional deficits in the esophagus, including a Zenker’s diverticulum, a neoplasm or an esophageal motility dysfunction [58, 80]. In recent years, pharyngo-esophageal HRM has provided useful insights into the process of swallowing by enabling the detection of esophageal dysmotility, with particular interest in upper and lower esophageal sphincters [81, 82]. Manometry studies, often in combination with VFSS or FEES, have shown that dysphagia in PD is associated with a high prevalence of esophageal motility disturbances [57, 80, 83, 84]. However, the impact of these alterations on swallowing and their role in influencing the clinical management of dysphagia remain to be clarified [58].

Clinicians should keep in mind that findings from clinical and instrumental investigations of swallowing may not be entirely representative of the patient’s eating and drinking performance in real life. Variables such as distractions, specific consistencies and bolus size, medications, motor fluctuations and dyskinesias may impact the testing results [85, 86]. Thus, it is important to observe patients in their usual eating and drinking habits, or alternatively gather this information in the case history or with questionnaires [87]. The therapeutic effect of the anti-parkinsonian drugs on swallowing function is highly variable and can affect results from swallowing investigations. Though the dopaminergic medications might improve dysphagia in some patients, in others, they either showed no effect or negatively affected the swallowing function, also depending on the stage of the disease [88,89,90]. Similarly, studies testing the effect of deep brain stimulation (DBS) on swallowing function have yielded conflicting findings, showing beneficial, absent or detrimental effects [91].

Once the diagnosis of dysphagia is provided, standardized methods to assess swallowing severity should be carried out to guide the best treatment strategy and for prognostic assessment. Most of the studies conducted in patients with PD have adopted the Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) [92]. A few studies have used other validated scales such as the Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale (DOSS) [93], and the Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) [94].

Relevance of dysphagia for the quality of life of patients with PD

Dysphagia negatively affects QoL in PD. The progression of swallowing difficulties may cause choking, coughing or breathing problems during the meal, and often leads to dietary restrictions and prolonged meal duration. Altogether, these changes have an important psychosocial burden for patients with PD because they may discourage or impair social activities and relationships [106,107,108,109]. Swallowing problems negatively influence wellbeing, self-confidence and social integrations [108], which in turn result in frustration and isolation. Depression is indeed frequently associated with reduced QoL in patients with PD with swallowing disorders [107, 110,111,112].

Moreover, difficulty in taking oral anti-parkinsonian therapy with consequent worsening of motor and non-motor symptoms is another problem that frequently affects patient’s QoL [113].

In the late stages of the disease, due to severe dysphagia, PEG placement becomes mandatory when medium/long-term enteral feeding is needed to prevent malnutrition, weight loss and aspiration. This interventional procedure is often not well accepted by the patients and their caregivers and may thus have a further negative impact on QoL [108, 114].

Though not specific for PD, the Swallowing Quality of Life (SWAL-QOL) is the most widely used questionnaire to assess the impact of dysphagia on the QoL of patients with PD both in the literature and in the clinical practice [107, 109, 115]. SWAL-QOL [116] assesses different aspects of the swallowing function that are experienced by the patient (i.e., food selection, social functioning, fear, eating duration, eating desire, communication) with a recall period of 1 month. The questionnaire is available and validated in several languages.

The 39-item Parkinson’s disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) and the short-form 8-item Parkinson’s disease Questionnaire (PDQ-8) are also used in PD to assess the psychosocial impact of dysphagia on QoL, but they are not specific for swallowing disturbances [117].

A limited number of studies have investigated the relationship between dysphagia severity and the impact on QoL [106, 112, 115, 118, 119]. The severity of dysphagia significantly affects QoL and the progression of the disease [12, 13, 120], though this relationship is not linear. In the study by Leow et al. [106], QoL deterioration was proportional to the progression of dysphagia, and the subjects who required diet modifications presented with significantly reduced SWAL-QOL scores.

Prognostic value of dysphagia and prognostics factors for dysphagia in PD

In this paragraph, we focus on the impact of dysphagia on comorbidities and life expectancy of subjects with PD, and on the factors that are associated to dysphagia severity.

The incidence of aspiration pneumonia is more than three-fold higher in PD subjects than age-matched controls [12], and patients with dysphagia are more likely to die of pneumonia than those with normal swallowing [121]. Presence of comorbidities (e.g., chronic respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular disease, chronic renal or liver disease) and lower level of compliance to enteral feeding in PD patients with severe dysphagia increases the risk of pneumonia and choking [122]. Weight loss is more frequent in patients with PD with eating problems [113], and the risk of malnutrition appears to be dependent on dysautonomic symptoms including dysphagia [9].

Survival after onset of dysphagia is poor in PD [120]. Moreover, the severity of dysphagia represents the most important prognostic factor for the occurrence of death in the later stages of the disease. [13, 14] Pneumonia represents the most common cause of death in PD [123, 124]. Aspiration of solid food, liquids, saliva or gastric contents represents the leading cause of pneumonia in this patient population, [11] and it is significantly associated with survival from diagnosis [125].

As regards the factors that may be associated to dysphagia severity, disease progression is associated with more severe swallowing difficulties. [6, 41, 126] Furthermore, an impaired cough response has a negative impact on dysphagia severity [52]. This agrees with the notion that integrity of pharyngeal–laryngeal sensitivity and cough efficiency influence the risk of aspiration pneumonia, as reflex and voluntary cough are important mechanisms of airway protection during swallowing [27, 127]. The association between pneumonia and reduced oral hygiene is well documented [128, 129]. However, we did not find any specific evidence regarding the prognostic value of reduced oral hygiene on dysphagia and/or PD outcome. Yet, it is conceivable that poor oral hygiene may have a negative impact on dysphagic patients with PD. Finally, a relationship between cognitive impairment, dysphagia severity and risk of aspiration pneumonia has been shown in PD [6, 130].

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of the present work are worth mentioning. The first regards the recruitment of participants, which, in the absence of a strictly codified methodology for selection, was based on practical considerations and on their voluntary acceptance of our invitation. This approach led to the formation of an expert group with a prevalent representation of neurologists compared to other specialists, and a prevalence of Italian specialists compared to specialists from other countries. Thus, it is possible that the statements elaborated by this panel group do not reflect entirely the point of view of the wider international medical and scientific communities. It is worth noting, however, that we put in place several measures to involve as many experts in the field as possible and that, once the panel was created based on voluntary adhesion, the ruling process was supported by a thorough revision of the data available from the literature. This approach seemed the best compromise between spending more time in trying to include a larger group of experts and the need to deliver this consensus in an acceptable time frame to provide timely guidance to clinician on a critical issue in the management of PD patients. Another shortcoming of our consensus statements is that PD patients, their carers or representatives were not involved in the process. Indeed, their contribution would have certainly been relevant, especially as regards the quality of life topic .

Unmet needs, areas for future research

This consensus process identified several critical areas for the timely and correct diagnosis of dysphagia in PD that could not be properly addressed by the panel of experts due to the lack of reliable evidence. Future studies need to focus on the reliability of clinical methods to screen and assess dysphagia in PD and should better define the conditions when instrumental investigations are required. Other areas worth attention are the development of validated all-inclusive (clinical and instrumental) scales for rating dysphagia severity in PD, and of PD-specific tools to assess the impact of dysphagia on QoL.

In particular, there was agreement among the consensus participants that future research should aim to address the following additional questions:

-

1)

What are the pathophysiological elements of dysphagia in PD and their neurophysiological correlates in terms of oropharyngeal sensory and motor impairment?

-

2)

What is the role played by esophageal dysmotility in PD?

-

3)

In which way malnutrition and dehydration in PD affect dysphagia severity and the risk of complications?

-

4)

Does PEG insertion change the prognosis and QoL of patients with severe dysphagia?

-

5)

Are there useful biomarkers for the early detection of PD-related dysphagia, e.g. levels of substance P in saliva?[133]

-

6)

How should we choose the best timing of clinical and instrumental evaluation in relation to the motor fluctuation of patients in specific situations (severe dyskinesias, DBS, etc.)?

-

7)

Are the biomechanical or pathophysiological elements of dysphagia in PD affected by different anti-parkinsonian treatment strategies or different complications?

References

Elbaz A, Carcaillon L, Kab S, Moisan F (2016) Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Rev Neurol (Paris) 172:14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2015.09.012

Armstrong MJ, Okun MS (2020) Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease. JAMA 323:548. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.22360

Jankovic J (2008) Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79:368–376. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045

Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M et al (2015) MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 30:1591–1601. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26424

Pflug C, Bihler M, Emich K et al (2018) Critical dysphagia is common in Parkinson disease and occurs even in early stages: a prospective cohort study. Dysphagia 33:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9831-1

Miller N, Allcock L, Hildreth AJ et al (2009) Swallowing problems in Parkinson disease: frequency and clinical correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80:1047–1049. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2008.157701

Kalf JG, de Swart BJM, Bloem BR, Munneke M (2012) Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18:311–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.006

Sapir S, Ramig L, Fox C (2008) Speech and swallowing disorders in Parkinson disease. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 16:205–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282febd3a

Barichella M, Cereda E, Madio C et al (2013) Nutritional risk and gastrointestinal dysautonomia symptoms in Parkinson’s disease outpatients hospitalised on a scheduled basis. Br J Nutr 110:347–353. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512004941

Martinez-Ramirez D, Almeida L, Giugni JC et al (2015) Rate of aspiration pneumonia in hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol 15:104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0362-9

Fujioka S, Fukae J, Ogura H et al (2016) Hospital-based study on emergency admission of patients with Parkinson’s disease. eNeurologicalSci 4:19–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensci.2016.04.007

Akbar U, Dham B, He Y et al (2015) Incidence and mortality trends of aspiration pneumonia in Parkinson’s disease in the United States, 1979–2010. Park Relat Disord 21:1082–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.06.020

Cilia R, Cereda E, Klersy C et al (2015) Parkinson’s disease beyond 20 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 86:849–855. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2014-308786

Fabbri M, Coelho M, Abreu D et al (2019) Dysphagia predicts poor outcome in late-stage Parkinson’s disease. Park Relat Disord 64:73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.02.043

Institute of Medicine (US) (1992) Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From Development to Use. Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). PMID: 25121254

Nair R, Aggarwal R, Khanna D (2011) Methods of formal consensus in classification/diagnostic criteria and guideline development. Semin Arthritis Rheum 41:95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.12.001

Candiani G., Colombo C. et al (2009) Come organizzare una conferenza di consenso. Manuale metodologico, Roma, ISS-SNLG.

AAN (American Academy of Neurology) (2011) Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual. MN: The American Academy of Neurology. Ed. St. Paul

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al (2016) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Rev Esp Nutr Humana y Diet. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Monteiro L, Souza-Machado A, Pinho P et al (2014) Swallowing impairment and pulmonary dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: the silent threats. J Neurol Sci 339:149–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.004

Hartelius L, Svensson P (1994) Speech and swallowing symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis: a survey. Folia Phoniatr Logop 46:9–17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000266286

Takizawa C, Gemmell E, Kenworthy J, Speyer R (2016) A systematic review of the prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, head injury, and pneumonia. Dysphagia 31:434–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9695-9

Ali G, Wallace K, Schwartz R et al (1996) Mechanisms of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Gastroenterology 110:383–392. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566584

Bird MR, Woodward MC, Gibson EM et al (1994) Asymptomatic swallowing disorders in elderly patients with parkinson’s disease: a description of findings on clinical examination and videofluoroscopy in sixteen patients. Age Ageing 23:251–254. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/23.3.251

Wallace KL, Middleton S, Cook IJ (2000) Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology 118:678–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70137-5

Roy N, Stemple J, Merrill RM, Thomas L (2007) Dysphagia in the elderly: preliminary evidence of prevalence, risk factors, and socioemotional effects. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116:858–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940711601112

Troche MS, Schumann B, Brandimore AE et al (2016) Reflex cough and disease duration as predictors of swallowing dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 31:757–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9734-6

Sampaio M, Argolo N, Melo A, Nóbrega AC (2014) Wet voice as a sign of penetration/aspiration in Parkinson’s disease: does testing material matter? Dysphagia 29:610–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9552-7

Buhmann C, Bihler M, Emich K et al (2019) Pill swallowing in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective study based on flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Park Relat Disord 62:51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.02.002

Nóbrega AC, Rodrigues B, Torres AC et al (2008) Is drooling secondary to a swallowing disorder in patients with Parkinson’s disease? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 14:243–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.08.003

Rodrigues B, Nóbrega AC, Sampaio M et al (2011) Silent saliva aspiration in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 26:138–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.23301

van Wamelen DJ, Leta V, Johnson J et al (2020) Drooling in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence and progression from the non-motor international longitudinal study. Dysphagia 35:955–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10102-5

Claus I, Muhle P, Suttrup J et al (2020) Predictors of pharyngeal dysphagia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 10:1727–1735. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-202081

Potulska A, Friedman A, Królicki L, Spychala A (2003) Swallowing disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 9:349–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1353-8020(03)00045-2

Lam K, Kwai Yi Lam F, Kwong Lau K et al (2007) Simple clinical tests may predict severe oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 22:640–644. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21362

Loureiro F, Caline A, Sampaio M et al (2013) A Swallowing Clinical Assessment Score (SCAS) to evaluate outpatients with Parkinson’s disease. Pan Am J Aging Res 1:16–19

Singer C, Weiner WJ, Sanchez-Ramos JR (1992) Autonomic dysfunction in men with Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neurol 32:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1159/000116810

Manor Y, Giladi N, Cohen A et al (2007) Validation of a swallowing disturbance questionnaire for detecting dysphagia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 22:1917–1921. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21625

Simons JA, Fietzek UM, Waldmann A et al (2014) Development and validation of a new screening questionnaire for dysphagia in early stages of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20:992–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.06.008

Branco LL, Trentin S, Augustin Schwanke CH et al (2019) The Swallowing Clinical Assessment Score in Parkinson’s Disease (SCAS-PD) is a valid and low-cost tool for evaluation of dysphagia: a gold-standard comparison study. J Aging Res 2019:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7984635

Kalf JG, Borm GF, De Swart BJ et al (2011) Reproducibility and validity of patient-rated assessment of speech, swallowing, and saliva control in parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92:1152–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.011

Minagi Y, Ono T, Hori K et al (2018) Relationships between dysphagia and tongue pressure during swallowing in Parkinson’s disease patients. J Oral Rehabil 45:459–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12626

Vogel AP, Rommel N, Sauer C et al (2017) Clinical assessment of dysphagia in neurodegeneration (CADN): development, validity and reliability of a bedside tool for dysphagia assessment. J Neurol 264:1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8499-7

Volonte’ MA, Porta M, Comi G (2002) Clinical assessment of dysphagia in early phases of Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci 23:s121–s122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100720200099

Belo LR, Gomes NAC, Coriolano MDGWDS et al (2014) The relationship between limit of dysphagia and average volume per swallow in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 29:419–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-013-9512-7

Buhmann C, Flügel T, Bihler M et al (2019) Is the Munich dysphagia Test-Parkinson’s disease (MDT-PD) a valid screening tool for patients at risk for aspiration? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 61:138–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.10.031

Curtis JA, Troche MS (2020) Handheld cough testing: a novel tool for cough assessment and dysphagia screening. Dysphagia 35:993–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10097-z

Kanna SV, Bhanu K (2014) A simple bedside test to assess the swallowing dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 17:62–65. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.128556

Miyazaki Y, Arakawa M, Kizu J (2002) Introduction of simple swallowing ability test for prevention of aspiration pneumonia in the elderly and investigation of factors of swallowing disorders. Yakugaku Zasshi 122:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi.122.97

Mari F, Matei M, Ceravolo MG et al (1997) Predictive value of clinical indices in detecting aspiration in patients with neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 63:456–460. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.63.4.456

Clarke CE, Gullaksen E, Macdonald S, Lowe F (2009) Referral criteria for speech and language therapy assessment of dysphagia caused by idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 97:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.1998.tb00605.x

Troche MS, Brandimore AE, Okun MS et al (2014) Decreased cough sensitivity and aspiration in Parkinson disease. Chest 146:1294–1299. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0066

Pitts LL, Morales S, Stierwalt JAG (2018) Lingual pressure as a clinical indicator of swallowing function in Parkinson’s disease. J Speech Lang Hear Res 61:257–265. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-17-0259

Coates C, Bakheit AMO (1997) Dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neurol 38:49–52. https://doi.org/10.1159/000112902

Ertekin C, Tarlaci S, Aydogdu I et al (2002) Electrophysiological evaluation of pharyngeal phase of swallowing in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 17:942–949. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.10240

Alfonsi E, Versino M, Merlo IM et al (2007) Electrophysiologic patterns of oral-pharyngeal swallowing in parkinsonian syndromes. Neurology 68:583–589. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000254478.46278.67

Jones CA, Ciucci MR (2016) Multimodal swallowing evaluation with high-resolution manometry reveals subtle swallowing changes in early and mid-stage Parkinson disease. J Parkinsons Dis 6:197–208. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-150687

Suttrup I, Suttrup J, Suntrup-Krueger S et al (2017) Esophageal dysfunction in different stages of Parkinson’s disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 29:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12915

Ding X, Gao J, Xie C et al (2018) Prevalence and clinical correlation of dysphagia in Parkinson disease: a study on Chinese patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 72:82–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2017.100

Giraldo-Cadavid LF, Leal-Leaño LR, Leon-Basantes GA et al (2017) Accuracy of endoscopic and videofluoroscopic evaluations of swallowing for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Laryngoscope 127:2002–2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26419

Stroudley J, Walsh M (1991) Radiological assessment of dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Br J Radiol 64:890–893. https://doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-64-766-890

Tomita S, Oeda T, Umemura A et al (2018) Video-fluoroscopic swallowing study scale for predicting aspiration pneumonia in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 13:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197608

Gaeckle M, Domahs F, Kartmann A et al (2019) Predictors of penetration-aspiration in Parkinson’s disease patients with dysphagia: a retrospective analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 128:728–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419841398

Nagaya M, Kachi T, Yamada T, Igata A (1998) Videofluorographic study of swallowing in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 13:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00009562

Argolo N, Sampaio M, Pinho P et al (2015) Swallowing disorders in Parkinson’s disease: impact of lingual pumping. Int J Lang Commun Disord 50:659–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12158

Argolo N, Sampaio M, Pinho P et al (2015) Videofluoroscopic predictors of penetration-aspiration in Parkinson’s disease patients. Dysphagia 30:751–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-015-9653-y

Wakasugi Y, Yamamoto T, Oda C et al (2017) Effect of an impaired oral stage on swallowing in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Oral Rehabil 44:756–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12536

Schiffer BL, Kendall K (2019) Changes in timing of swallow events in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 128:22–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489418806918

Hammer MJ, Murphy CA, Abrams TM (2013) Airway somatosensory deficits and dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 3:39–44. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-120161

Suntrup S, Teismann I, Wollbrink A et al (2013) Magnetoencephalographic evidence for the modulation of cortical swallowing processing by transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroimage 83:346–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.055

Warnecke T, Suttrup I, Schröder JB et al (2016) Levodopa responsiveness of dysphagia in advanced Parkinson’s disease and reliability testing of the FEES-Levodopa-test. Park Relat Disord 28:100–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.04.034

Grosso M, Duce V, Fattori B et al (2015) The value of oro-pharyngo-esophageal scintigraphy in the management of patients with aspiration into the tracheo-bronchial tree and consequent dysphagia. North Am J Med Sci 7:533–536. https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.170628

Mamolar Andrés S, Santamarina Rabanal ML, Granda Membiela CM et al (2017) Swallowing disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Otorrinolaringol (English Ed) 68:15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otoeng.2017.01.003

Jones CA, Hoffman MR, Lin L et al (2018) Identification of swallowing disorders in early and mid-stage Parkinson’s disease using pattern recognition of pharyngeal high-resolution manometry data. Neurogastroenterol Motil 30:e13236. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13236

Ertekin C, Pehlivan M, Aydoǧdu I et al (1995) An electrophysiological investigation of deglutition in man. Muscle Nerve 18:1177–1186. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.880181014

Cosentino G, Tassorelli C, Prunetti P et al (2020) Reproducibility and reaction time of swallowing as markers of dysphagia in parkinsonian syndromes. Clin Neurophysiol 131:2200–2208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2020.06.018

Kim J, Watts CR (2020) A comparison of swallow-related submandibular contraction amplitude and duration in people with Parkinson’s disease and healthy controls. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1766566

Alfonsi E, Merlo IM, Ponzio M et al (2010) An electrophysiological approach to the diagnosis of neurogenic dysphagia: implications for botulinum toxin treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.174698

Alfonsi E, Restivo DA, Cosentino G et al (2017) Botulinum toxin is effective in the management of neurogenic dysphagia. Clinical-electrophysiological findings and tips on safety in different neurological disorders. Front Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00080

Su A, Gandhy R, Barlow C, Triadafilopoulos G (2017) Clinical and manometric characteristics of patients with Parkinson’s disease and esophageal symptoms. Dis Esophagus 30:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/dow038

Blais P, Bennett MC, Gyawali CP (2019) Upper esophageal sphincter metrics on high-resolution manometry differentiate etiologies of esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31:e13558. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13558

Taira K, Fujiwara K, Fukuhara T et al (2021) Evaluation of the pharynx and upper esophageal sphincter motility using high-resolution pharyngeal manometry for Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 201:106447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106447

Bassotti G, Germani U, Pagliaricci S et al (1998) Esophageal manometric abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 13:28–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00009546

Castell JA, Johnston BT, Colcher A et al (2001) Manometric abnormalities of the oesophagus in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 13:361–364. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00275.x

Monte FS, da Silva-Júnior FP, Braga-Neto P et al (2005) Swallowing abnormalities and dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 20:457–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20342

Broadfoot CK, Abur D, Hoffmeister JD et al (2019) Research-based updates in swallowing and communication dysfunction in parkinson disease: implications for evaluation and management. Perspect ASHA Spec Interes Groups 4:825–841. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_pers-sig3-2019-0001

Martin-Harris B, Jones B (2008) The videofluorographic swallowing study. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 19:769–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2008.06.004

Coelho M, Marti MJ, Tolosa E et al (2010) Late-stage Parkinson’s disease: the Barcelona and Lisbon cohort. J Neurol 257:1524–1532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5566-8

Lim A, Leow LP, Huckabee ML et al (2008) A pilot study of respiration and swallowing integration in Parkinson’s disease: “On” and “Off” levodopa. Dysphagia 23:76–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-007-9100-9

Michou E, Hamdy S, Harris M et al (2014) Characterization of corticobulbar pharyngeal neurophysiology in dysphagic patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:2037-2045.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.03.020

Suttrup I, Warnecke T (2016) Dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 31:24–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-015-9671-9

Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB et al (1996) A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 11:93–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00417897

O’Neil KH, Purdy M, Falk J, Gallo L (1999) The dysphagia outcome and severity scale. Dysphagia 14:139–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00009595

Crary MA, Carnaby Mann GD, Groher ME (2005) Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86:1516–1520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.049

Pitts T, Troche M, Mann G et al (2010) Using voluntary cough to detect penetration and aspiration during oropharyngeal swallowing in patients with Parkinson disease. Chest 138:1426–1431. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-0342

Silverman EP, Carnaby G, Singletary F et al (2016) Measurement of voluntary cough production and airway protection in parkinson disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 97:413–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.10.098

Hegland KW, Okun MS, Troche MS (2014) Sequential voluntary cough and aspiration or aspiration risk in Parkinson’s disease. Lung 192:601–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-014-9584-7

Moreau C, Devos D, Baille G et al (2016) Are upper-body axial symptoms a feature of early Parkinson’s disease? PLoS One 11:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162904

Fuh JL, Lee RC, Wang SJ et al (1997) Swallowing difficulty in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 99:106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0303-8467(97)00606-9

Johnston BT, Castell JA, Stumacher S et al (1997) Comparison of swallowing function in Parkinson’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 12:322–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.870120310

Ws Coriolano Md, R Belo L, Carneiro D, G Asano A, et al (2012) Swallowing in patients with Parkinson's disease: a surface electromyography study. Dysphagia 27(4):550-555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9406-0

Lee KD, Koo JH, Song SH et al (2015) Central cholinergic dysfunction could be associated with oropharyngeal dysphagia in early Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm 122:1553–1561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-015-1427-z

Ellerston JK, Heller AC, Houtz DR, Kendall KA (2016) Quantitative measures of swallowing deficits in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 125:385–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489415617774

Wang C-M, Shieh W-Y, Weng Y-H et al (2017) Non-invasive assessment determine the swallowing and respiration dysfunction in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 42:22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.05.024

Lee WH, Lim MH, Nam HS et al (2019) Differential kinematic features of the hyoid bone during swallowing in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 47:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2019.05.011

Leow LP, Huckabee M-L, Anderson T, Beckert L (2010) The Impact of dysphagia on quality of life in ageing and Parkinson’s disease as measured by the Swallowing Quality of Life (SWAL-QOL) questionnaire. Dysphagia 25:216–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9245-9

Manor Y, Balas M, Giladi N et al (2009) Anxiety, depression and swallowing disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15:453–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.11.005

Plowman-Prine EK, Sapienza CM, Okun MS et al (2009) The relationship between quality of life and swallowing in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24:1352–1358. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.22617

Van Hooren MRA, Baijens LWJ, Vos R et al (2016) Voice- and swallow-related quality of life in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Laryngoscope 126:408–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25481

Barone P, Antonini A, Colosimo C et al (2009) The PRIAMO study: a multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24:1641–1649. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.22643

Han M, Ohnishi H, Nonaka M et al (2011) Relationship between dysphagia and depressive states in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Park Relat Disord 17:437–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.006

Miller N, Noble E, Jones D, Burn D (2006) Hard to swallow: dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Age Ageing 35:614–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl105

Lorefält B, Granérus AK, Unosson M (2006) Avoidance of solid food in weight losing older patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01454.x

White H, King L (2014) Enteral feeding pumps: efficacy, safety, and patient acceptability. Med Devices (Auckl)7:291-298. https://doi.org/10.2147/MDER.S50050. PMID: 25170284; PMCID: PMC4146327

Carneiro D, Coriolano Md Ws, Belo LR et al (2014) Quality of life related to swallowing in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 29:578–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9548-3

McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE et al (2002) The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: I conceptual foundation and item development. Dysphagia 15:115–121

Storch A, Schneider CB, Wolz M et al (2013) Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology 80:800–809. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318285c0ed

Silbergleit AK, Lewitt P, Junn F et al (2012) Comparison of dysphagia before and after deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 27:1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25259

Wang C-M, Tsai T-T, Wang S-H, Wu Y-R (2020) Does the M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory correlate with dysphagia-limit and the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale in early-stage Parkinson’s disease? J Formos Med Assoc 119:247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2019.05.005

Müller J, Wenning GK, Verny M et al (2001) Progression of dysarthria and dysphagia in postmortem-confirmed parkinsonian disorders. Arch Neurol 58:259–264. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.58.2.259

Lo RY, Tanner CM, Albers KB et al (2009) Clinical features in early Parkinson disease and survival. Arch Neurol 66:1353–1358. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.221

Goh KH, Acharyya S, Ng SYE et al (2016) Risk and prognostic factors for pneumonia and choking amongst Parkinson’s disease patients with dysphagia. Park Relat Disord 29:30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.05.034

Morgante L, Salemi G, Meneghini F et al (2000) Parkinson disease survival: a population-based study. Arch Neurol 57:507–512. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.57.4.507

Auyeung M, Tsoi TH, Mok V et al (2012) Ten year survival and outcomes in a prospective cohort of new onset Chinese Parkinson’s disease patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:607–611. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2011-301590

Hussain J, Allgar V, Oliver D (2018) Palliative care triggers in progressive neurodegenerative conditions: an evaluation using a multi-centre retrospective case record review and principal component analysis. Palliat Med 32:716–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318755884

Robbins J, Gensler G, Hind J et al (2008) Comparison of 2 interventions for liquid aspiration on pneumonia incidence: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 148:509–518. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00007

Ebihara S, Saito H, Kanda A et al (2003) Impaired efficacy of cough in patients with Parkinson disease. Chest 124:1009–1015. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.124.3.1009

El-Solh AA (2011) Association between pneumonia and oral care in nursing home residents. Lung 2011189(3):173-180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-011-9297-0. Epub 2011 Apr 30. PMID: 21533635

El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A et al (2004) Colonization of dental plaques: a reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital-acquired pneumonia in institutionalized elders. Chest. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.126.5.1575

Lee JH, Lee KW, Kim SB et al (2016) The functional dysphagia scale is a useful tool for predicting aspiration pneumonia in patients with Parkinson disease. Ann Rehabil Med 40:440–446. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2016.40.3.440

Malmgren A, Hede GW, Karlström B et al (2011) Indications for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and survival in old adults. Food Nutr Res 55:1–6. https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v55i0.6037

Cereda E, Cilia R, Klersy C et al (2014) Swallowing disturbances in Parkinson’s disease: a multivariate analysis of contributing factors. Park Relat Disord 20:1382–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.09.031

Schröder JB, Marian T, Claus I et al (2019) Substance P saliva reduction predicts pharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurol 10:1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00386

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The consensus conference was funded by the IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made an intellectual contribution through discussion at a consensus meeting and approved the manuscript. Paper writing: GC, MA (these authors contributed equally to this paper). Study supervision: EA, CM, AS, CT. Intellectual content: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Research questions based on PICO

Participants/population

Patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Intervention(s), exposure(s)

Questions on screening and diagnosis: presence and absence of oropharyngeal dysphagia, and any diagnostic test or screening test.

Questions on prognosis: oropharyngeal dysphagia as exposures.

Question on treatment: any treatment of oropharyngeal dysphagia.

Comparator(s)/control

Not applicable.

Main outcome(s)

The primary outcome of the systematic review is to gather evidence on: (1) screening approach to oropharyngeal dysphagia in PD; (2) definition of the diagnostic criteria of oropharyngeal dysphagia in PD; (3) definition of the prognostic value of oropharyngeal dysphagia on QoL and PD outcome.

Such evidence will inform the statements of a Multinational Consensus Conference to provide guidance to clinicians on the above listed topics.

Appendix 2. Search strategy on MEDLINE

("deglutition disorders"[MeSH] OR ("deglutition disorder"[All Fields] OR "deglutition disorders"[All Fields] OR "swallowing disorders"[All Fields] OR "swallowing disorder"[All Fields] OR ("deglutition disorders"[MeSH Terms] OR ("deglutition"[All Fields] AND "disorders"[All Fields]) OR "deglutition disorders"[All Fields] OR "dysphagia"[All Fields]))).

AND

("Parkinson Disease"[Mesh] OR ("Parkinson's disease"[All Fields] OR "Parkinson disease"[All Fields] OR Parkinson[All Fields])).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cosentino, G., Avenali, M., Schindler, A. et al. A multinational consensus on dysphagia in Parkinson's disease: screening, diagnosis and prognostic value. J Neurol 269, 1335–1352 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10739-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10739-8