Abstract

The interplay between stress and chemical processes is a fundamental aspect of how rocks evolve, relevant for understanding fracturing due to metamorphic volume change, deformation by pressure solution and diffusion creep, and the effects of stress on mineral reactions in crust and mantle. There is no agreed microscale theory for how stress and chemistry interact, so here I review support from eight different types of the experiment for a relationship between stress and chemistry which is specific to individual interfaces: (chemical potential) = (Helmholtz free energy) + (normal stress at interface) × (molar volume). The experiments encompass temperatures from -100 to 1300 degrees C and pressures from 1 bar to 1.8 GPa. The equation applies to boundaries with fluid and to incoherent solid–solid boundaries. It is broadly in accord with experiments that describe the behaviours of free and stressed crystal faces next to solutions, that document flow laws for pressure solution and diffusion creep, that address polymorphic transformations under stress, and that investigate volume changes in solid-state reactions. The accord is not in all cases quantitative, but the equation is still used to assist the explanation. An implication is that the chemical potential varies depending on the interface, so there is no unique driving force for reaction in stressed systems. Instead, the overall evolution will be determined by combinations of reaction pathways and kinetic factors. The equation described here should be a foundation for grain-scale models, which are a prerequisite for predicting larger scale Earth behaviour when stress and chemical processes interact. It is relevant for all depths in the Earth from the uppermost crust (pressure solution in basin compaction, creep on faults), reactive fluid flow systems (serpentinisation), the deeper crust (orogenic metamorphism), the upper mantle (diffusion creep), the transition zone (phase changes in stressed subducting slabs) to the lower mantle and core mantle boundary (diffusion creep).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Pressure influences all chemical reactions, including those that occur in the Earth spanning simple transformations such as diamond to graphite to complex ones including many phases. This implies that stress, a more general state in which forces per unit area are different in different directions, must also influence reactions. Interactions of stress and chemical processes affect many aspects of Earth behaviour such as the rheology of the mantle when undergoing diffusion creep, reactive fluid flow in deforming media and fracturing of minerals due to reaction. One possible cause of intermediate-depth earthquakes in subduction zones is the volume reduction during the transformation of basalt to eclogite possibly accommodated by huge stress buildups (Nakajima et al. 2013). These interactions are of practical importance in understanding for example how olivine fractures during serpentinisation, with implications for CO2 sequestration (Kelemen et al. 2011). Addition of water to anhydrite, forming gypsum, led to uplift and damage to an entire town when the solid volume increase of the reaction overcame the weight of overlying rocks (Schweizer et al. 2019); yet elsewhere the same reaction occurred without apparent deformation [e.g. Fig. 2c of De Paola et al. (2008)]. These examples show it is important to understand how stress and chemical processes influence each other.

Our understanding of the effect of pressure on reaction is underpinned by standard thermodynamics, which describes systems where there is no differential stress, and the stress can be described as isotropic. However, there is no agreed theory which extends thermodynamics to include anisotropic stress and how it affects reaction and since many parts of the Earth are under stress, this is a significant gap in our understanding. It might be expected that the effects of stress are the same on rocks as on other polycrystalline materials so that Earth science could call upon such work, but to the writer’s knowledge, there is no text summarising those effects in any branch of science. There are several widely quoted works on mathematical foundations, but those works are not always tied directly to the experiments conducted in other studies. In Earth science opinions differ on the importance of stress, in terms of the magnitude of effects on chemical equilibrium and even whether equilibrium exists (Hobbs and Ord 2017; Powell et al. 2018; Tajcmanova et al. 2015; Wheeler 2014, 2018). Those papers are all based on mathematical arguments and it would be useful to substantiate and test the contrasting predictions through experiments. Here I show that there are several different types of experiments already published over several decades which independently point to the same mathematical description of the effects of stress on chemical processes: namely, a single equation that applies at interfaces between crystals and relates local stresses to chemistry.

To proceed, definitions of pressure and stress are needed. “Stress” is a second rank tensor σ from which the force per unit area on a notional surface of any orientation can be deduced. In this contribution, compressive stresses are taken as positive. “Pressure” strictly is used to imply an isotropic state of stress, in which the force per unit area is the same in all directions; commonly the phrase “hydrostatic pressure” is used, even though fluids need not be involved. Then, the well-established theory of thermodynamics is “hydrostatic thermodynamics”, and extensions of it to address stressed systems are aspects of “non-hydrostatic thermodynamics”. The nomenclature is perhaps not the best but is firmly established.

The word “pressure” has been used in different ways in different works both within and outside Earth science. Some works define pressure as the average of the three principal stresses: here, to avoid ambiguity, I call this the “mean stress” σm. It is a simple and unique function of the stress tensor. Other works sometimes use the word pressure for the force per unit area across a particular interface, the “normal stress” σn. This value depends on the interface orientation. It can have different values even for a single stress tensor because interfaces of different orientation are always present in a polycrystal. The symbol P might also be used to indicate hydrostatic pressure in a reference system (not the actual system), pressure in one part of a system and so forth; I point out its differing meanings in the works I review.

In this contribution, I give a brief mathematical background and then show how descriptions of eight different types of experiment are in accord with a particular equation. Each work uses different language and notation, so it is necessary to explain some details to illustrate the extent to which the works overlap. Then I discuss the consequences of the equation, for a broader perspective on what the experiments tell us and to show how it should form a key part of grain-scale mathematical models: such models are a prerequisite for predicting larger-scale behaviour.

Brief mathematical framework

Some maths is required here to understand how the various experiments reviewed are linked back by the authors to basic thermodynamics. The physics of stress is well established; in terms of its chemical effects, although there is controversy, any mathematical description of the effects of stress must reduce to hydrostatic thermodynamics when the stress is isotropic and pressure has a single clearly defined value.

Hydrostatic thermodynamics

In hydrostatic thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy is a number which is minimised in a system at equilibrium. For each phase, it has a functional dependence G(P, T) on pressure and temperature. G is measured in J or J/mol. If we express G in J, and the number of moles of a particular chemical component as N, then the chemical potential of that component is μ\((=\partial \mathrm{G}/\partial \mathrm{N}\)). In this contribution, I do not address solid solutions (although the discussion here is relevant for them) because the experiments reviewed do not involve solid solutions. Consequently, if we express G in J/mol for a phase (as will be done in the rest of this contribution), then the chemical potential of a component with the composition of that phase is equal to G. This allows the thermodynamics of stressed systems to be related back to hydrostatic thermodynamics.

When there is a mixture of reactants and products then the overall “driving force” for a reaction is often written as ΔG = Gproducts−Greactants, with suitable coefficients to ensure the reaction is balanced using chosen mineral formulae (e.g. MgSiO3 versus Mg2Si2O6 for enstatite). ΔG has units of J/mol and depends on the chosen coefficients. For instance the reaction albite = jadeite + quartz could also be written as 2 albite = 2 jadeite + 2 quartz. The latter would have a ΔG double that of the former, but so long as the reaction is defined in a consistent fashion then this is not a problem. Changes in Helmholtz free energy ΔF and molar volume ΔV should be defined using the same reaction coefficients (notation used here is summarised in Table 1). In this contribution, there is a need in places to refer to the solid volume change in a reaction ΔVs which again should be defined using the same reaction coefficients as used for defining the other Δ quantities but omitting those related to the fluid. In a hydrostatic system, the driving forced for reaction can be defined as affinity. There are two IUPAC definitions for affinity, but they are numerically identical. Affinity is relevant for quantifying nucleation of product phases (Pattison et al. 2011) but nucleation is outside the scope of this contribution. For an ongoing reaction involving existing phases we can write affinity A = − ΔG. When we are dealing with stoichiometric phases this can also be written in terms of chemical potentials. For instance, if we take albite into the stability field of jadeite and quartz then we would have A = μalb − μjd − μq. In stressed systems referring to μ and A rather than to G and ΔG proves advantageous.

Nonhydrostatic thermodynamics

There is a common assumption that a generalised version of Gibbs free energy must exist in a stressed system, and once the generalised form of G is established, the equations, methods and databases of hydrostatic thermodynamics can be used to calculate equilibria: the choice is to use mean stress. In contrast, others (Paterson 1973; Wheeler 2018) argue that there is no Gibbs free energy in a stressed system, and local chemical potentials vary from place to place, governed by different interface orientations and local normal stresses. Both approaches reduce to hydrostatic thermodynamics when stress is isotropic, but their predictions are quite different, so clarification is required. Given the ambiguity over the existence of G, I express the mathematics in terms of local chemical potentials. There is a single equation which applies at an interface and, I will argue, is supported by the experiments I review:

Here μ is chemical potential (of a chemical component with the same composition as the solid), F is the Helmholtz free energy per mole (not itself strongly dependent on stress) and V is the molar volume of the crystalline solid (again not strongly dependent on stress since crystalline solids are not very compressible). The equation indicates that chemical potential is a function of each particular interface and its orientation, and is roughly linear in σn, although there are circumstances in which the small non-linear dependence on F on stress also plays a role in explaining experimental results. There are also circumstances in which the curvature of the interface is large enough that surface energy makes a significant contribution. If the surface or interface energy is γ then a term is added as follows.

where κ is the curvature (positive for convex-out surfaces). Since differences in chemical potential drive transport and reaction, and chemical potential depends on interface orientation I argue that there is no chemical equilibrium in a stressed system (Wheeler 2014, 2018). In hydrostatic thermodynamics, for a single component solid the chemical potential is equal to the Gibbs free energy per mole as follows:

When stress is isotropic, the normal stress is equal to P regardless of interface orientation, and Eq. 1 reduces to Eq. 3. Equilibrium is possible since interface orientation no longer appears in the mathematical description. In contrast to Eq. 1 other works e.g. (Tajcmanova et al. 2015; Verhoogen 1951) assert that for a single component solid the chemical potential and Gibbs free energy are as follows:

where σm is the mean stress—not dependent on any particular interface. Again, this reduces to Eq. 3 when stress is isotropic.

Equation 1 was proved by Gibbs for a stressed solid next to a fluid. Disputes arise when its use is extended to solid/solid boundaries, and confusion arises when there is an absorbed aqueous film along a solid/solid boundary. Such films are commonly described as “fluid films” and then maybe incorrectly thought to be at fluid pressure Pf, but in general, they carry stress (Gratier et al. 2013; Wheeler 2018). I assert that existing theoretical work in Earth and other branches of science justifies the use of Eq. 1 as a start to describe chemical behaviour at all incoherent interfaces (Wheeler 2018), which comprise the overwhelming majority of crystalline interfaces in the Earth. However theoretical arguments on their own are not conclusive, in terms of whether the theory is accepted and how it is to be applied. So, in this contribution, I summarise 8 different types of the experiment (Table 2, Fig. 1) that support Eq. 1, and in some instances explain why the experiments contradict Eq. 4. The experiments encompass a wide range of conditions: temperatures from − 100 to 1300 degrees C and pressures from 1 bar to 1.8 GPa (Table 3). Because the use of G is at best ambiguous in stressed systems, it is necessary to rephrase the mathematical development used in published works in terms of chemical potential, without changing the actual mathematical results. Similarly, rather than refer to ΔG as a driving force for reaction, I generalise the affinity. As discussed for a hydrostatic system A can be written as a difference between chemical potential of reactants and products—according to Eq. 1 in a stressed system that will be dependent on the interfaces involved. In Wheeler (2014) I used the idea of a reaction pathway to describe which interfaces are involved in the reaction. This is relevant for relating the various experiments I review to each other, and the pathways are shown by grey arrows in Fig. 1. The term “generalised affinity” was in fact used previously by Schmid et al. (2009), to explain an experiment involving a solid-state reaction under stress which is discussed later.

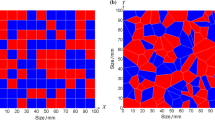

Schematic diagrams to illustrate the experiments described. In each diagram green indicates a particular solid, other solids are labelled, and pale blue indicates an aqueous solution held in a notional beaker (grey). Red arrow indicates maximum compressive stress, pink arrow indicates minimum compressive stress, and grey arrow indicates the transport pathway for one or more chemicals. In most experiments stress is heterogeneous on some scale as described in Table 2

The experiments I discuss are directly related to Earth science but some involve soluble salts and overlap with other research fields. Chemical potential and local stresses cannot easily be measured directly, so there are inferences built into the justification of Eq. 1 which will be discussed in each case. It can be used to formulate driving forces for various processes, using some mathematical details summarised in Appendix 1. In all the processes discussed, kinetics are important and are not always easy to quantify, and stress is generally heterogeneous. Despite these issues, I will show that Eq. 1 provides explanatory power.

Experimental support for the equation

Stressed solid next to fluid

This first section discusses “free” surfaces of solids next to fluids. Mechanical equilibrium at the surface dictates that fluid pressure Pf equals normal stress σn in the solid. If σn is fixed, changes in tangential stresses σt might give rise to observable effects: changes in the chemical potential of the solid will give rise to changes in local equilibrium concentration in the fluid.

Ristic et al. (1997) grew alum from a supersaturated solution, comparing unstressed crystals with others under tension. The tensile stress led to a reduction in growth rate relative to the unstressed state. The alum deformed plastically to a small extent but the work shows that the dislocations involved could not have influenced growth kinetics. The growth rate will be a function of the affinity (driving force) \({A= \mu }^{solution}- {\mu }^{solid}\). A slower growth rate would be in accord with the chemical potential of the solid under stress (with tangential stress σt ≠ normal stress σn) being higher than its value under unstressed conditions, reducing the affinity. McLellan (using Eq. 1) shows that, regardless of whether the tangential stress is relative tension or compression, the chemical potential always increases under stress; a version of that derivation is given in Appendix 1. Consequently, the driving force for growth is smaller in the stressed situation, in accord with the observed slower growth rate. In contrast Eq. 4 predicts that “the potential is thus increased by a compression, decreased by a traction” (Verhoogen 1951). Thus, crystals under tension (from context, his “traction” means tension) would decrease their solubility, and the growth rate should be faster. Equation 4 is therefore not in accord with observations.

Morel and den Brok (2001) undertook experiments on crystals under compressive as well as tensile stress. They chose sodium chlorate (NaClO3) because it has elastic–brittle mechanical behaviour at room temperature, thus avoiding any complications introduced by plastic deformation. In each experiment, they drilled a hole in the crystal to create a heterogeneous stress state, with varying states of tangential stress around the hole (including compressive and tensile). The fluid involved was “saturated sodium chlorate solution” (i.e. a solution that would be in equilibrium with an unstressed crystal at 1 bar), with a small additional dilution, so the dissolution of the solid would be expected. They compared the dissolution behaviour of stressed and unstressed crystals. Regardless of whether the tangential stress was tension or compression, they found that stressed crystals dissolved faster than unstressed ones. They quantified the excess driving force due to stress in terms of the change in elastic strain energy given as their Eq. 1.

I give a more general justification of their equation (based on Eq. 1 here) in Appendix 1. Their discussion can therefore be rephrased in terms of changes in μ given by Eq. 1. Morel and den Brok (2001) use this to show that the change in driving force (Δμ) for dissolution due to stress (~ 0.1 J/mol) is minor in comparison to the driving force due to undersaturation (~ 60 J/mol), yet the actual change in dissolution rate is disproportionately large. Therefore, these experiments are in qualitative agreement with Eq. 1 in terms of the sign, but not quantitative agreement. One explanation may relate to instabilities and roughening of the stressed surface which might modify the average dissolution rate. Such instabilities are discussed in the next section.

Ostapenko et al. (1972) undertook experiments on stressed halite in solution, motivated by the need to understand, in their words, “two diametrically opposed theories” about the chemical potential of a solid under conditions of non-hydrostatic stress. They are referring to the difference between Eq. 1 (they cite Gibbs) and Eq. 4 (they cite Verhoogen (1951)). This is a reminder that the controversy I mention here is not new. One aspect of their interpretation requires modification (Appendix 3) but this does not affect their conclusion. In brief, they used an optical method to detect minute changes in concentration adjacent to a crystal of halite in solution. They applied compressive stresses and found no detectable changes in concentration adjacent to the crystal. They argued that Eq. 4 predicts changes in concentration large enough that their method would have detected them, while Eq. 1 predicts concentration changes below the detectability limit. Consequently, this paper rejected Eq. 4 in favour of Eq. 1.

Stressed solid next to fluid - instabilities

den Brok and Morel (2001) put crystals of alum under compressive stress in a slightly undersaturated solution and discovered that instabilities develop. As in their experiments on sodium chlorate described above, they drilled a hole in the crystal to create a heterogeneous stress field, amplified around the hole. They found grooves developed in the initially planar crystal surface and the groove spacing in some experiments was smaller at higher stress. For example, for local amplified stress of 15 MPa near the hole, the groove wavelength was 20–40 μm (Fig. 2).

Grooves showing surface instability in alum crystal under compressive stress (up-down) surrounded by solution. Bulk stress was 2.7 + 0.2 MPa, amplified to 13–14 MPa around the hole (den Brok and Morel 2001)

To explain this they invoked theory from materials science. Asaro and Tiller (1972) and Grinfeld (1986) show mathematically that a stressed planar interface is chemically unstable with respect to the development of periodic undulations above a certain wavelength, named after these works as Asaro-Tiller-Grinfeld (ATG) instabilities. In an undulation, the normal stress remains fixed but the normal direction varies spatially. The stress field near the surface is then non-uniform, though it becomes uniform over a distance of a few wavelengths inside the solid (Srolovitz 1989).

Figure 3 shows that in this non-uniform stress state the elastic strain energy (Helmholtz free energy) is more in a trough than in a peak. At any interface, normal stresses must balance on either side, so here σn = Pf ≈ 0 in comparison to the larger tangential stresses. In accord with Eq. 1 and setting σn = 0, there is a chemical potential difference between troughs and peaks. This is a driving force for dissolution in troughs and precipitation at peaks, so any perturbation will amplify regardless of wavelength. However, the surface energy provides an opposite effect. The troughs are concave outwards and peaks are convex outwards, so there is a driving force for peaks to dissolve and material to precipitate in troughs, and any perturbation will diminish: the minimum energy configuration is a flat surface. Analysis incorporating both effects (Eq. 10 of Srolovitz (1989), which is Eq. 2 here) shows that for short wavelengths the surface energy effect dominates but for long wavelengths λ the stress effect dominates. Srolovitz made a “crude” initial estimate of critical wavelength as,

Helmholtz free energy near an undulating crystal surface when a N–S differential stress is applied, displayed in multiples of the uniform value in the crystal interior. Calculated using Matlab PDE solver with Poisson’s ratio 0.3; when scaled this way, the pattern does not depend on the Young’s modulus value

where γ is surface energy. Using this den Brok and Morel (2001) showed that for local amplified stress of 15 MPa near the hole, the wavelength is predicted to be 35 μm. It is observed to be 20–40 μm. I note here that a more detailed analysis shows that perturbations are predicted to amplify for,

There is a wavelength at which a maximum growth rate is predicted, a small multiple of λ0 depending on the kinetics (e.g. surface diffusion, volume diffusion, evaporation—condensation). Assuming that the instability develops via diffusion through the fluid, analogous to evaporation—condensation [Sect. 3B of Srolovitz (1989)] then the maximum growth rate is for λ = 2λ0 giving 28 μm for the alum example. There is broad agreement between predicted and observed wavelengths, and larger stresses decrease observed wavelengths, so ATG theory (based on Eq. 1 and Eq. 2) has explanatory power, though more experiments are needed to consolidate the link to theory.

In subsequent sections I deal with situations in which the second-order terms in stress do not have a significant effect, so Eqs. 1 and 3 can both be considered linear in stress.

Pressure solution

Pressure solution is a deformation mechanism where strain is accommodated by diffusion of material through an aqueous grain boundary film from interfaces with high normal stress to those with low normal stress. The film “should only with the greatest care be treated as continuous with the fluid in the pore space and is perhaps better treated as a separate thermodynamic phase” (Gratier et al. 2013); it is itself stressed. As material moves away from high-stress interfaces, shortening occurs parallel to σ1, and as the material precipitates at low-stress interfaces, extension occurs parallel to σ2 and/or σ3. Natural microstructures provide evidence for this, most clearly when the regions of precipitation have distinct features. Pore water may form part of the diffusion path in porous aggregates.

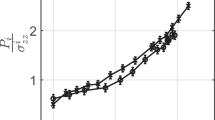

Figure 4 shows aspects of the flow law in experiments on pressure solution of halite from Spiers et al. (1990). The form of the flow law in deformation experiments, in general, can be described by strain rate being proportional to (stress)n × (grain size)−p. Other quantities such as temperature are involved but it is the exponents n and p which are relevant here as they give insight into the underlying processes. In experiments on pressure solution (e.g. Fig. 4) there are often two key features: first, the strain rate is linear in differential stress (n = 1) and secondly, it is inversely proportional to the cube of grain size (p = 3).

(a) Log–log plot of strain rate (volumetric compaction rate) versus effective stress σe, for the values of volumetric strain (ev) shown, for compaction of halite (Fig. 4 of Spiers et al. (1990)). Note slopes near 1. (b) Log–log plot of compaction rate versus grain size d (Fig. 5 of that work). Note slopes near − 3

A flow law fitting such observations can be derived theoretically beginning with a local equilibrium relationship between chemical potential and stress at an interface (e.g. Rutter (1983) Eq. 2)

which is the same as Eq. 1 above. The local equilibrium is between the stressed solid and its dissolved form in the adjacent grain boundary film or in an adjacent pore fluid

In pressure solution, we have long-range diffusive transport from high-stress interfaces to low-stress interfaces, through the grain boundary film. The driving force is then, for a single chemical component and ignoring σ2 for simplicity,

Note this quantity is not normally thought of as a chemical affinity, but it is consistent with other usage to call it that. The driving force is linear in the differential stress, so the strain rate is linear in differential stress, as observed (Newtonian viscosity), unless some kinetic factors are nonlinear. The full derivation of the flow law has been presented many times (Gratier et al. 2013; Rutter 1976, 1983). If local equilibrium is assumed between the stressed solid and the solid dissolved in the immediately adjacent grain boundary film, so diffusion is the main rate-controlling step, then

[e.g. (Rutter 1976)] where \(\dot{e}\) is strain rate, B a dimensionless constant, D is grain boundary diffusion coefficient, c is concentration of solute in grain boundary (mol/m3), w is grain boundary width, R the gas constant and d the grain size. The constant B depends on microstructural details such as porosity (Keszthelyi et al. 2016) and grain shape (Wheeler 2010), but what matters here is that the flow law predicts n = 1 and p = 3.

de Meer and Spiers (1995) show that for gypsum deforming by pressure solution, under certain circumstances the strain rate is proportional to the inverse grain size (p = 1). This is explained considering that dissolution and precipitation of the solid may be difficult; for example, for precipitation, thought to be rate controlling for gypsum, we require supersaturation in the pore fluid.

This means that the chemical potential difference \({\mu }_{1}^{gbf}- {\mu }_{3}^{gbf}\) which drives diffusion, in particular, is no longer derived from Eq. 6 and the flow law is modified by dissolution and precipitation rate terms e.g. Table 2.3, Eqs. 2.33 of Gratier et al. (2013). However, the key point is that Eq. 1 still underpins the derivation of the flow law via their Eq. 2.14 (Eq. 6 here).

Equation 4 has never been used to explain pressure solution phenomena, and it is difficult to see how it could help. For example, suppose we stress a single-phase polycrystal uniformly. Then Eq. 4 predicts that G and chemical potential would have a single value everywhere, and there would be no driving force for deformation by chemical transport.

Diffusion creep

Diffusion creep is similar to pressure solution except the grain boundaries are essentially dry (there may be some water molecules which enhance diffusion rates but there is no aqueous film) and an additional diffusion pathway may act through grain interiors by volume diffusion. Elliott (1973) first highlighted the similarities between the pressure solution and diffusion creep. Karato et al. (1986) found a deformation regime in fine-grained olivine where the stress exponent was n ~ 1.4 and the grain size exponent p ~ 2–3. To explain this they called upon flow laws such as derived by Raj and Ashby (1971). To derive that flow law, that work states the following.

“Chemical equilibrium in the boundary plane means that the chemical potential μ, of vacancies at, and immediately adjacent to a point on the boundary is related to the normal stress σn, acting on the boundary at that point [Raj and Ashby (1971) Eq. B2]:

where Ω is the atomic volume, and \({\mu }_{0}\) the chemical potential appropriate to a stress-free reference state”. Here they define chemical potential per atom rather than per mole. Noting that the chemical potential of a vacancy is minus the chemical potential of the missing atom, this is the same as Eq. 1 except that the relatively small second-order stress terms in the Helmholtz free energy have been neglected. Larché and Cahn (1985) include the second-order term but reiterate it is relatively small and can be neglected under many circumstances.

Raj and Ashby (1971) present flow laws (their Eqs. 22 and 23) with n = 1, and p = 2 (for volume diffusion) or p = 3 (for grain boundary diffusion). For the latter, using notation as in Eq. 7,

Note that the two equations have the same form except that the concentration c is missing in Eq. 8; the two equations are reconciled by recognising that the concentration c of a material in a solid boundary is equal to 1/V, and putting cV = 1 in Eq. 7 gives Eq. 8. The values of D are very different between pressure solution and diffusion creep but the form of the flow law is the same.

Using the flow laws for lattice and grain boundary diffusion creep Karato et al. (1986) appeal to volume diffusion (as they find p near 2) under dry conditions and grain boundary diffusion (as they find p near 3) in wet conditions. The stress exponent n > 1 is due to the operation of other deformation mechanisms in parallel with diffusion creep. As for pressure solution, then, Eq. 1 can be used to help explain the observed rheologies.

Force of crystallisation—single solid

Force of crystallisation is a phrase which covers several phenomena in which stress and chemical processes interact and is related to pressure solution. I suggest it is useful to distinguish two “end member” scenarios in which the phrase is used.

1. Experiments where dead weights are rested on crystals growing from supersaturated solutions (such as alum, Becker and Day (1916)). The crystal may be lifted, showing that the chemical process of crystallisation causes work to be done against an applied force. Here the force is applied externally, does not change, and the system is not confined.

2. Experiments where a solid reaction is mediated by fluid, and involves a solid volume increase, and occurs in a confined space may result in forces as the growing crystals push against their surroundings (Wolterbeek et al. 2016, 2017). The chemical processes give rise to stress, which can play a role in fracturing and lead to practical engineering problems. Because of the confinement, the volume change cannot be manifest, instead of volume is conserved and elastic stresses increase. Force is developed internally, it builds up through time, and the system is confined.

These are “end member” scenarios and in reality confined experiments may allow some displacements, for example, because the confining vessel is elastic (Wolterbeek et al. 2017) or deforms plastically (Ostapenko and Yaroshenko 1975). In both scenarios, chemical disequilibrium (e.g. CaO in the presence of water, water supersaturated with alum) causes new and existing phases to grow with some contribution from transport along with aqueous grain boundary films into interfaces under high stress.

Correns (1949) undertook experiments in which a crystal of alum was placed in a supersaturated solution, with a force applied from above by a weighted lever and pushrod. The sideways stress on the crystal was 1 bar, since the system was not confined, and the vertical stress was > 1 bar in accord with the pushrod force and the area over which it was applied. Despite the “extra” vertical force, crystal growth displaced the pushrod upwards; the maximum stress that would still allow upwards displacement of the pushrod depended on the level of supersaturation in the solution. At low supersaturations the relationship was linear and at high supersaturations, it was nonlinear and also depended on the crystal face being loaded (Fig. 5).

Relationships between supersaturation in an alum solution and vertical stress that can be supported by a growing crystal: Fig. 8 of Flatt et al. (2007), itself redrawn from Correns and Steinborn (1939). a) calculated curve from Eq. 12. b Curve fitted to data for stressed (111) faces (open triangle no growth, filled triangle growth). c Curve fitted to data for stressed (110) faces (open circle no growth, filled circle growth)

The figure includes a theoretical curve and to understand this we need an expression for chemical potential in stressed interfaces. When these potentials are lower than those in the surroundings, inwards diffusion will occur along with the interface, and upwards displacement can occur. Correns provided a framework for explaining the observations, but Flatt et al. (2007) point out various ambiguities so here we will refer to their subsequent commentary. Considering the growth of a crystal from supersaturated solution, Steiger (2005) states “the chemical potential μp of a crystal face under pressure p takes the form” (his Eq. 4, verbatim)

Despite describing p as “pressure”, from the context it is clear the system is not under hydrostatic (isotropic) pressure p, but p is actually the normal stress across a loaded interface—so I choose here to rename the chemical potential in a stressed interface as \({\mu }_{\sigma }\). Steiger defines μ0 is the chemical potential of the solid in the unstressed reference state, and w as molar [elastic] strain energy, so that \({\mu }_{0}+w=F\). Noting that Vm is the molar volume of the solid in the stressed state, his Eq. 4 is seen to be the same as Eq. 1 here. Chemicals will diffuse into a stressed interface from a pore fluid if affinity \({\mu }^{pf}- {\mu }_{\sigma }=A>0\) so the maximum stress that can be supported is when those two chemical potentials are equal. Because the alum solution has more than one ionic species in solution it is sensible to write the relationship in terms of activity; the link to concentration comes later.

where \({\mu }_{0}^{pf}\) is a reference chemical potential at reference activity \(a\). Choosing this reference as the chemical potential of the solid under hydrostatic pressure p, written here as \({\mu }_{p}\) then this equation can be expressed in terms of the activity \({a}_{s}\) of dissolved material that would be in equilibrium with that solid at hydrostatic pressure p, i.e. the activity at which the solution is saturated.

Then the maximum stress that can be sustained is when A = 0 and

But \({\mu }_{\sigma }\) and \({\mu }_{p}\) are both given by Eq. 1. Assuming uniform stress in the crystal, the Helmholtz free energy has the same value on stressed and free interfaces, as does the molar volume, so

which is rearranged to

Here the LHS is sometimes referred to as “crystallization pressure”, but it should be noted it is not a pressure: it is the numerical difference between the normal stress on a loaded interface and the pressure in a nearby fluid. When Fig. 5 was first drawn, Correns and Steinborn (1939) implicitly assumed that activity was equal to concentration so

Flatt et al. (2007) and Appendix 2 explain that Correns had not considered the ionic nature of his alum solution, so his equation relating chemical potential to concentration was incorrect; instead

where n is about 3.5. The calculated curve in Fig. 5 when recalculated no longer fits the data. Rather than modify Eq. 9, Flatt et al. (2007) suggest that for a number of reasons the measured “pressures” (stresses) were actually higher than those presented, but the original works to not provide enough experimental detail to be sure. Attempts to repeat the experiments have proved difficult (Caruso and Flatt 2014). There are many other experiments, focussed on building stone deterioration, which are interpreted using Eq. 10 but they are generally complex and are not quite direct tests of the equation.

Force of crystallisation—two or more solids

So far we have considered a system with just one solid, and a supersaturated solution. Force of crystallisation is also manifest in systems where reactions involve one solid reacting to another, mediated by and involving fluid. The examples I cite are all hydration reactions, one with CO2 also involved, where experiments and theory have been compared: lime to portlandite (Ostapenko and Yaroshenko 1975; Wolterbeek et al. 2017), bassanite to gypsum (Ostapenko and Yaroshenko 1975; Skarbek et al. 2018), periclase to brucite (Ostapenko 1976; Zheng et al. 2018) and olivine carbonation (Xing et al. 2018).

In these papers a particular equation appears repeatedly, relating force of crystallisation to the ΔG of reaction, i.e. the change in Gibbs free energy between reactants and products, or departure from chemical equilibrium. Some works assert that G is not defined in a stressed system (Kamb 1961; Paterson 1973; Wheeler 2018), therefore such expressions should be treated with care. However, in the equation below it is defined as the ΔG the reaction would have if all reactants and products were under hydrostatic fluid pressure P, which remains a well-defined number (from context, it means G(reactants) – G(products)). Then

using my notation and where ΔVs is the solid volume change (in m3/mol) calculated using the same reaction coefficients as used for ΔG. Note the similarity with Eq. 11 except instead of V we have ΔVs in the denominator. There is some uncertainty over this equation, for example (Kelemen et al. 2011) write “the volume used in the denominator of [their] Eq. 7 should probably be ΔVs, as written” (my italics), so it is useful to trace the history of its derivation. Wolterbeek et al. (2017) derive an expression like Eq. 13 (their Eq. 13) beginning with their Eq. 6 which apart from notation is the same as Eq. 1.

The approximation is indicated because the surface energy term (Eq. 2) is omitted (Wolterbeek pers. comm.). The earliest use of Eq. 13 known to me is in Ostapenko and Yaroshenko (1975) though that work does not refer to Eq. 1. In Appendix 4 I show how their approach is equivalent to that of Wolterbeek et al. (2017) and explained by Eq. 1. I argue that the equation relates to a specific reaction pathway, in this case, water moving into an interface where both lime and portlandite are stressed, followed by lime reacting to portlandite as CaO moves across that interface. Wolterbeek et al. (2017) indicate there are other possibilities, saying “In principle, any thermodynamic driving force that can produce a supersaturation with respect to the solid product phase can generate a FoC, as long as precipitation can occur under confined conditions, e.g. within load-bearing grain contacts” and focus on one such scenario. Other pathways are in principle possible, for example, lime dissolving directly in pore fluid and precipitating portlandite in pores in which case I assert that Eq. 13 would not apply.

In some hydration experiments, the stresses recorded during the ongoing reaction are much lower than those calculated using Eq. 13. Ostapenko and Yaroshenko (1975), Wolterbeek et al. (2017) and Zheng et al. (2018) all suggest that the grain boundary film is squeezed out at high normal stress, shutting down the transport pathway before the maximum predicted stress is reached. Ostapenko (1976) modified the explanation, proposing that water molecules diffuse into the periclase-brucite interfaces and cause volume expansion (hence stress) “by enlargement of inter-grain spaces” before reaction. Then the reaction itself, considering the volumes of brucite, periclase and water, has a small (in fact negative) volume change in comparison to a large positive volume change of solids. Hence reaction would not affect the stress state. This explanation was not developed into a quantitative model, but it does draw attention to the possibility that the locations of volume changes in the microstructure (depending on kinetics) are likely to influence stresses produced. That is the same as saying that specific reaction pathways have different effects, and I address this in the Discussion. A further reason why measured stresses are below theoretical maxima is that pores are clogged by reaction products, inhibiting further reaction (Wolterbeek et al. 2017). Skarbek et al. (2018) present a numerical model involving compaction of the porous bassanite + gypsum aggregate as well as reaction, which successfully predicts the initial expansion of the aggregate, i.e. work done against the applied stress, and then compaction. This includes an empirical reaction rate not explicitly coupled so cannot be regarded as a test of Eq. 1, but it would be illuminating to include that equation in future models.

Xing et al. (2018) made porous cylindrical olivine “cups”, filled them with olivine sand, and added NaHCO3 aqueous solution. This is out of equilibrium so carbonation and hydration reactions result, to form magnesite and other products. Evolution was observed in a synchrotron. In some experiments, the cups cracked, with fracturing beginning on the outer surfaces whilst the interior was reacting. Grain positions were tracked using the synchrotron data and this gave a strain estimate of 0.03 which, in the elastic outer layer of the cup, gives a stress estimate of ~ 300 MPa which they note is in accord with estimates of “crystallisation pressure” (Kelemen et al. 2013). However, the cracks are not at the actual reaction site, and there many signs of dissolution in the interior, which would not be conducive to building up forces. It is not easy to link the experiments back to fundamental theory.

This section has shown that experiments more complex systems show evidence for “force of crystallisation” but in no case is it easy to link the observations back to theory. In the discussion, I will reiterate that consideration of multiple reaction pathways will help to overcome these problems.

Polymorphic transformations under stress

Here I will document experiments showing that the direction of reaction in some are in accord with Eq. 1, and for one other is claimed to be in accord with Eq. 4. Vaughan et al. (1984) studied the transformation of olivine to spinel under stress in a germanate analogue system, using a Griggs apparatus with confining pressure of 1–1.8 GPa and differential stress of 0.1 to 1.2 GPa. This reaction is analogous to that which defines the 410 km seismic discontinuity in the mantle.

Under stress, the microstructure showed anisotropic growth: the stress orientation had a direct effect on reaction (Fig. 6). Spinel nucleated and grew preferentially on interfaces perpendicular to σ1. To explain the growth, they first noted that reaction kinetics under hydrostatic pressure can be described “fairly well”. For reactions under stress they state: “For the case of nonhydrostatic stress, however, the formulation is less straightforward because the generalization of the Gibbs function to nonhydrostatic situations is somewhat controversial and often misunderstood”, citing reviews from Kamb (1961) and Paterson (1973). This is a reminder that the controversies motivating this contribution are not new. Vaughan et al. (1984) went from first principles to derive a condition for chemical equilibrium between olivine and spinel across an interface, in their notation

Optical micrographs of spinel forming from germanate olivine, with maximum stress aligned top to bottom. Top: crossed polarizers, spinel in black: note residual lenses of olivine perpendicular to maximum stress (Fig. 1 of Vaughan et al. (1984)). Bottom: uncrossed and crossed polarizer images of spinel “fingers” (elongate parallel to maximum stress) separated by very thin spikes of olivine (Fig. 3 of that work)

where

Here u is internal energy and s is entropy. Since F = u − Ts (Appendix 1), we see that their g is equal to μ here, as in Eq. 1. Consequently, their Eq. 2 states that local equilibrium between olivine and spinel is described by

where μ is defined as in Eq. 1, supporting that definition of chemical potential in a stressed system. Although they use the symbol g, and state it will reduce to the usual Gibbs free energy when the stress is hydrostatic, they do not call it Gibbs free energy, and make clear it is anisotropic as follows. “When the stress is nonhydrostatic, however, g varies with the orientation of the interface because σn does. It is this property that provides an explanation of the anisotropic grain growth that we observe”. They elaborate upon this by defining a driving force for reaction, in my notation

If A > 0 there is a drive for olivine to convert to spinel at the particular interface under consideration. Expanding Eq. 16 we find

where Δ indicates the difference (value for product spinel) – (value for reactant olivine). Note that this is different to Eq. 6 but both are derived from Eq. 1. In the polymorphic reactions discussed here, long-range transport of chemicals is not required: to turn one polymorph into another only requires transport across an interface, not along it. Hence, only a single local normal stress value appears in mathematics. Since ΔV < 0, A is a maximum where σn is a maximum, namely where σn = σ1. On other interfaces A may be smaller (slower reaction) or even negative (no, or reverse reaction). This explains why spinel nucleates first, or preferentially, on olivine boundaries perpendicular to σ1. When it grows, the spinel then forms “fingers” parallel to σ1. This is in accord with a greater driving force on interfaces perpendicular to σ1, hence faster growth parallel to σ1. Vaughan et al. (1984) use Eq. 17 to explain finger growth morphology and aspect ratio in some detail.

At higher stresses, the reaction is shear-induced across coherent interfaces (Burnley and Green 1989). Under these circumstances, a thermodynamic description different to Eq. 1 may apply (Heidug and Lehner 1985; McLellan 1980). The olivine to spinel transition (via wadsleyite) is very important in the Earth but most solid-state transformations proceed across incoherent interfaces; coherent interfaces are not discussed further here.

Kirby et al. (1991) used polymorphic transformations in water ice (ice I to denser ice II) as analogues for transformational faulting in the mantle. As the sample of ice, I shortened under stress, there was very little radial strain: the volume reduction due to transformation was the main deformation mechanism. Direct microstructural observations were not made; instead, the indium metal jackets, peeled off the samples, were used to determine the surface topography of the samples. Lenses of ice II, elongate perpendicular to σ1, were diagnosed. The authors assert: “Samples that transformed in bulk did so at essentially the same σ1 values as the pressures at which undeformed ice I transformed under hydrostatic conditions”. What they mean is that if ice transforms under hydrostatic pressure P, it also transforms under a more general state of stress when σ1 = P. This study is in accord with the olivine to spinel study in terms of driving force and microstructure, and in accord with Eq. 1.

Hirth and Tullis (1994) caused quartz to transform to coesite in experiments investigating the brittle-plastic transition in quartz. The coesite formed, in part, along grain boundaries perpendicular to σ1. To clarify the thermodynamics of this reaction they plotted the conditions of coesite formation against σ1 (Fig. 7, inverted triangles) and separately against mean stress σm.

The effects of differential stress on the quartz to coesite transformation from Fig. 5 of (Richter et al. 2016): round symbols are from that work; earlier results from Hirth and Tullis (1994) and Zhou et al. (2005) are incorporated. Filled symbols show conditions where coesite was found, plotted using mean stress (above) and maximum principal stress (below)

As Fig. 7 shows, using σm as a proxy for pressure does not easily explain the formation of coesite. This, together with the preferential formation of coesite along grain boundaries perpendicular to σ1, seems to be in accord with an equation similar to Eq. 17 for the olivine to spinel transformation. The authors point out that the stress field in the experiment will be heterogeneous, and near the pistons (where most coesite formed) the stress might be roughly isotropic. In those regions locally σm ≈ σ1, implying ambiguity in how the coesite formation is to be interpreted. However, away from these “strain shadows” coesite is still found, and preferentially along grain boundaries perpendicular to σ1, implying “the importance of σ1 in controlling the transition”. This illustrates that it is not straightforward to test fundamental thermodynamic ideas through experiments. Stress fields are commonly heterogeneous on the scale of a sample (Table 2), and even if they are initially uniform on that scale, there are likely to be grain-scale variations brought on in part by the volume changes associated with the reaction.

Richter et al. (2016) revisited the quartz to coesite transformation, using two modified Griggs apparatus, and simple shear of a layer of quartz (initially powder) rather than pure shear of a cylinder. The layer was confined between two strong pistons cut at 45 degrees to the apparatus axis, so shortening was manifest as simple shear in the quartz layer. They found that “σ1 is the critical parameter for the quartz-to-coesite transformation—not Pc or σm” (Fig. 7 circles, and diamonds from Zhou et al. (2005)). This is in agreement with Hirth and Tullis (1994) as discussed above, but with a different strain geometry hence extending the scope. Richter et al. (2016) also document the reverse transformation of coesite back to quartz when σ1 fell below the local equilibrium value (numerically, the value of isotropic pressure for equilibrium between quartz and coesite). During pure shear, the local strain shadows result from friction on the pistons, whereas in simple shear the friction drives an approximately uniform deformation across the width of the quartz layer, except at the ends of that layer where the pistons no longer overlap due to shear displacement. Microstructures figured in Richter et al. (2016) do show some clustering and patterns formed of coesite grains (e.g. their Fig. 9) but those patterns are themselves distributed uniformly across the slab.

Cionoiu et al. (2019) undertook experiments where an ellipsoidal strong alumina inclusion was embedded in calcite and then taken to high-pressure conditions with a uniaxial load. Aragonite was produced in a non-uniform pattern, particularly above and below the inclusion. A mechanical model of the stress field is used to show that the pattern of σm mimics the pattern of aragonite abundance and thus the experiments are claimed to support Eq. 4. Do they prove that equation though? Consider the following points.

1. As the authors point out, the reaction was not completed: calcite remains in the aragonite bearing areas. Kinetics thus need to be considered, which makes it less easy to prove the link between aragonite distribution and stress-related driving forces.

2. There were temperature variations within the sample: these were modelled but again making interpretation less easy.

3. The stress was calculated using a 2D model with viscous power-law rheology for calcite. So, the effects of aragonite rheology are not accounted for, nor is the direct contribution of the aragonite volume reduction on the strain, nor are 3D effects.

4. There is scope for alternative explanations: for example, variation in σ1, which is not illustrated in that work. By definition, σ1 > σm so anywhere that σm might trigger a reaction (because it is above the hydrostatic pressure for equilibrium), σ1 would also. A test could be made in the lower mean stress regions, where σ1 might be high enough to trigger a reaction but σm might be too low, but the required information is not given in the paper.

5. Fletcher (2015) modelled a microstructure of square grains of two polymorphs arranged in a chessboard pattern. He modelled the effect of stress on reaction using Eq. 1 (implicit in his Eq. 1), including reaction on both low and high-stress interfaces. He showed that the net direction and rate of reaction would then be governed by mean stress σm. This does not mean that an equilibrium exists governed by σm, and the results break down as soon as elongate grain are considered (Fletcher 2015; Wheeler 2015). However, the model might assist in explaining the results of Cionoiu et al. (2019) in a way that accords with Eq. 1 if one assumes that we see a quenched “snapshot” of an evolving system. The model is of more general significance because it is a precise description of what happens when two reaction pathways operate in parallel (here, the pathways relate to the reaction at low and high-stress interfaces).

So, these are intriguing experiments but for these five reasons fall short of “proof” that Eq. 4 applies rather than Eq. 1: there is scope for more such investigations. One key point of agreement, which is made elsewhere here as well, is “… the locally resolved knowledge of the stress-state is essential to better understand the bulk deformation and material property changes”.

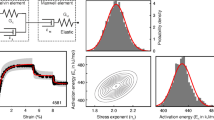

Solid-state reaction with volume change

In metamorphic reactions solid volume changes are ubiquitous, but it remains unclear how these are accommodated, and how the accommodation mechanisms affect reaction rate. As described in “Force of crystallisation—two or more solids”, it seems that volume changes give rise to stresses in reactions involving water. Fracturing can result from stresses caused by solid-state volume change (e.g. coesite as inclusions in garnets transforming to quartz (Gillet et al. 1984)). It is hard to envisage how volume changes, in general, can occur without giving rise to local stresses in some fashion, and there may be feedbacks between stress and chemical processes. To understand such possibilities better, Milke et al. (2009) and Schmid et al. (2009) studied the reaction between olivine and quartz to grow orthopyroxene, involving a 6% volume reduction. If we imagine the reactants floating in fluid, which is not involved in the reaction except as a diffusion pathway in a system that changes volume easily so as to maintain pressure, then hydrostatic thermodynamics would describe the driving force for reaction. However, that is not the setting for solid-state reactions through much of the Earth; instead, solids are surrounded by other solids and porosity is negligible. Milke et al. (2009) hypothesised that, if one mineral were included in a matrix of the other, this volume change was too large to be accommodated by elastic strain; plastic strain would be required for the matrix to collapse inwards around the inclusion. They designed experiments in which olivine was embedded in quartz (so the quartz would have to deform) and quartz was embedded in olivine (so the olivine would have to deform). They argued that the intrinsic kinetics of orthopyroxene reaction rim growth would be the same in both configurations, so the effects of matrix deformation could be distinguished separately. This was shown to be the case, as reaction rims for quartz in an olivine matrix were for example 10.3 μm wide whilst those for olivine in a quartz matrix were 6.1 μm under identical imposed conditions. The quartz matrix was stronger and inhibited growth.

To quantify the effect Schmid et al. (2009) provided a combined mechanical and thermodynamic theory, based on an idealised spherically symmetric system. Their model is, in brief, as follows: in the next paragraph, I will suggest how it may be rephrased and provide additional insights. Suppose the imposed large-scale pressure is P, then the overall driving force for the reaction would be, under hydrostatic conditions

where the enstatite formula is Mg2Si2O6 and Ω0 is the reaction affinity at pressure P. However, in a solid system, volume change must be accommodated, and stresses build up—in this case, a state of relative radial tension in the matrix, as it must deform so as to collapse around the growing reaction rim. Stresses will modify affinity. They consider a radial stress σr (with tension as positive but I will rewrite using compression as positive as in the rest of this contribution). Far from the inclusion, we will have σr = P, the far-field confining pressure. Near the inclusion, σr decreases with 1/r3 where r is the distance from the centre. Assuming that σr on either side of the reaction rim is the same, their Eq. (26) gives the effect of stress on what they call “generalized reaction affinity” as

where P is the “far field” or imposed pressure. As \({\sigma }_{r}<P\) this reduces affinity and slows the reaction rim growth rate. They use this result to derive an overall reaction rate (their Eq. (29)) which shows that reaction rate is slower for higher matrix viscosity and zero when the matrix cannot deform plastically (infinite viscosity).

I now re-express what they say, without changing the mathematics itself but showing some additional implications. G is undefined in the stressed system (though the definition of Ω0 in hydrostatic reference system can be retained). Instead consider chemical potentials of the three phases, specifically on interfaces perpendicular to σr, assuming these are where the phases dissolve and precipitate (as in standard reaction rim models where growth proceeds by dissolution and precipitation on interfaces parallel to the rim). Then the affinity for that particular reaction pathway (i.e. involving those particular interfaces) is, using Eq. 1,

Numerically we recover Eq. (26) of Schmid et al. (2009), So, their approach is in accord with Eq. 1 and is then shown to be in accord with observed rim growth and known rheologies of quartz and olivine. There is an additional implication of re-expressing their argument. The affinity as defined here depends on a particular reaction pathway: exchange of chemicals from one side of the reaction rim to the other). There is then the possibility of different reaction pathways with different affinities (c.f. Wheeler (2014)). For example, if the matrix deforms by diffusion creep, chemicals for the reaction might be supplied from radial interfaces (under high normal stress \({\sigma }_{\theta }>P\)) and a different expression for affinity will result.

Discussion

All of the experiments I describe are qualitatively or quantitatively in accord with Eq. 1 as summarised in the last column of Table 2, apart from that of Cionoiu et al. (2019) (type 7) which could perhaps be reinterpreted. I cannot see how pressure solution (type 3) and diffusion creep (4) could be explained using thermodynamics based on mean stress, I cannot see how such an approach could explain oriented microstructures (6), and for olivine, ice, and quartz it is not in accord with conditions for polymorphic transformation (7). Surely at a fundamental level, we need consistent mathematics to explain all the experiments I refer to so in the rest of the discussion I focus on implications of Eq. 1.

Other driving forces for reaction

Changes in hydrostatic pressure and temperature are fundamental drives for reaction. I argue here that stress is important, and so is surface energy as noted in Eq. 2 and “Stressed solid next to fluid-instabilities”. Dislocations trapped in lattices increase energy as well. This is in truth not a distinct form of energy and the driving force it provides can be described by Eq. 1. Near dislocations, stresses are locally large and the Helmholtz free energy is elevated. Thus, regions near dislocations are less stable and more soluble, which explains why dislocations are picked out as pits by etching. Usually, the dislocation energies are averaged to provide a simple link between energy and dislocation density [e.g. Wintsch and Dunning (1985)]. Figure 8 shows a visual comparison of three driving forces [c.f. Fig. 5 of Wheeler (1991)] using quartz properties (V = 2.7 × 10–5 m3/mol, γ = 1 J/m2, shear modulus = 48.4 GPa). Limits of box mark a change in the affinity of A = 1000 J/mol, with corresponding values of differential stress for (as an example) pressure solution (Eq. 6) using A/V, the radius of curvature 2 γV/A and dislocation density from Wintsch and Dunning (1985) Eq. 2. The precise values are not as important as the general illustration that stress provides a relatively large driving force for chemical change in relation to common values of curvature and dislocation density. The other driving forces are not discussed further here.

Three building-block ideas

Equation 1 is, I have shown, a foundation for understanding and quantification of processes where stress and chemistry interact. It is a local quantitative link between stress and chemical potential. It implies that there is no chemical equilibrium in a stressed system because chemical potentials take different values on different interfaces, so we need to describe system evolution in terms of kinetics. The third key idea is that of reaction pathways which have specific affinities (driving forces).

In Wheeler (2014) I introduced that idea and showed that the affinities varied by significant amounts but did not discuss the likelihood that multiple pathways will operate in parallel—in general, they will and an example is provided by comparing the types of experiment labelled 1 and 5 here. In both, the reaction is alum precipitation, but by different pathways. Figure 9 shows both pathways—surely in general they will both be active, but the papers I cite above have looked in detail at one or the other, not both. In an unstressed system, all pathways will have the same affinity but in a stressed system, the affinities may be different. The relative contribution of each pathway will be determined not just by the affinity but by the kinetics along that pathway. The kinetic factors are not intuitive. For example, one might imagine that free face precipitation is easy, and given that pathway also has a bigger affinity, it would be the dominant precipitation mechanism: yet in Correns’s experiment, the weight moves up so the pathway with smaller affinity still functions. I suggest that more complex pathways as in Wheeler (2014) will similarly work in parallel, with the overall evolution being a result of affinity combined with kinetic factors along each pathway. I also suggest that the reaction pathway idea, being flexible, could help explain the discrepancies between experiments and theory in the force of crystallisation experiments (“Force of crystallisation—two or more solids”). The works I refer to use Eq. 13 to predict stresses, but that is based on a particular reaction pathway in which the hydration product grows at solid–solid boundaries. Suppose instead that reaction products grow in pores (same reaction, different pathway)—then there is no reason for the matrix to deform, and no extra stress is to be expected. Growth in pores is the reaction pathway documented for gypsum dehydration (Bedford et al. 2017; Llana-Funez et al. 2012). In Table 2 I give examples of alternative reaction pathways for each type of experiment; each will have a different affinity to the main pathway discussed.

Combining experiment types 1 and 5 to illustrate the possibility of different reaction pathways. On left, grey arrows illustrate two possible transport pathways for solute (arrow length is of no significance). On right, diagram shows that the two pathways have different affinities (chemical potential drops) indicated by arrow lengths

Implications for understanding geological processes

Stress is ubiquitous in the Earth—even where large scale stresses are not apparent, there are likely to be grain-scale stresses, for example in porous media where fluid pressure differs from lithostatic. Volume change during the reaction can itself produce stress. Chemical processes may occur in response to such stresses but are unlikely to relax large scale stresses since these are produced by for example ridge push, slab pull, orogenic topography and density structure. These large scale stresses thus evolve on long length and time scales. If stresses relax whilst rocks are still hot, then the reaction might outlive deformation and syntectonic features might be overprinted. However, there are many examples in regional metamorphism where minerals demonstrably grow during deformation. Because stress prevails in the Earth, Eq. 1 can contribute to understanding and modelling diverse processes.

Diffusion creep and pressure solution in polymineralic rocks

Wheeler (1992) predicted, using Eq. 1, that chemical interactions between the two phases mean that polymineralic rocks might be much weaker than their single-phase equivalents. The argument was based on a simple microstructure illustrating that in monomineralic rocks diffusion creep is controlled by the slowest diffusing chemical but in polymineralic creep it might be controlled by a faster chemical. Experiments on olivine-orthopyroxene diffusion creep find, tentatively, the predicted weakening (Sundberg and Cooper 2008) and the migration of boundaries between those phases which underlies the prediction. Zhao et al. (2019) find that mixtures of olivine and clinopyroxene deform up to ∼30 times faster than either of the end-members when scaled to the same experimental conditions and appealed to the possibility that a faster diffusing species could account for this. A precise grain-scale model for polymineralic diffusion creep is yet to be created (Ford and Wheeler 2004) so currently, the links between theory and experiment are tantalising and require reinforcement. This is important since regions in the Earth undergoing pressure solution or diffusion creep are significant in size and/or significance – for example the lower mantle, major parts of active orogens (Wintsch and Yi 2002) and fault rocks undergoing slow compaction creep in between earthquakes (Sleep and Blanpied 1992).

Solid-state reaction under stress

Reactions occur under stress in regional metamorphism, in subducting slabs and in hydrothermal systems where fluid pressure differs from lithostatic. It is well known that there are feedbacks between deformation and metamorphism in nature (Teall 1885) and experiment (e.g. de Ronde and Stunitz (2007)) Brodie and Rutter (1985) document many feedbacks yet the direct effects of stress on reaction are not emphasised or quantified. For solid-state reactions Wheeler (2014) predicted, using Eq. 1, that stress may cause reactions to occur under quite different conditions to those predicted by hydrostatic thermodynamics, which could modify the way we interpret metamorphic assemblages in deformed rocks. That paper shows the effects of different reaction pathways in isolation, and the predictions could be enhanced by modelling effects of pathways operating in parallel, and by experimental tests.

Reactions involving fluid

When fluids are involved in reaction there are important consequences: fluids from dehydration may trigger earthquakes, and the reaction of CO2 bearing fluids with solids may be a way of sequestering CO2 and mitigating climate change (Kelemen et al. 2011). Experiments show visible links between dehydration reaction and deformation (Leclere et al. 2016; Rutter and Brodie 1988). With the possibility of fluid flow as well as reaction and deformation, these situations are more complex to model than the previous two topics, which are not themselves simple. This makes it particularly important to build on robust grain-scale models and the reaction pathway idea remains helpful. For example, during dehydration, the reaction pathway may be through pore fluid (Bedford et al. 2017; Llana-Funez et al. 2012) but on longer timescales, pressure solution may play a role and pathways involving grain boundaries will have an effect. During rehydration (or reaction with CO2 bearing fluids) the effects of local stresses built up during reaction are evident in e.g. the abundance of fracture patterns in partly serpentinised olivine. Such fracturing is likely to assist in establishing permeable pathways and sustaining reaction so we need to understand how chemical reactions induce stress sufficient to fracture rocks if we are to sequester CO2 in peridotite (Kelemen et al. 2011). Equation 13 has been used to predict the stresses involved (Kelemen et al. 2011; Plümper et al. 2012) but I suggest here it relates to just one of many possible reaction pathways. Different reaction pathways will have different effects: microstructures in nature and experiment and in situ studies will help to determine which pathways operate.

Tectonic overpressure

This contribution is not about tectonic overpressure but is relevant for that topic. Tectonic overpressure (or underpressure) is defined as (mean stress)—(lithostatic pressure), where lithostatic pressure is calculated by integrating the density-depth profile e.g. Schmalholz et al. (2014). In dynamic situations, numerical models predict that overpressure can be considerable. This may influence the development of metamorphic assemblages so there is some overlap with the topic of this contribution. To my knowledge, the great majority of works on overpressure relate it to metamorphism by (often implicitly) assuming that mean stress takes the role of pressure in controlling assemblages. As my contribution here shows, this may not be the case. Gerya (2015) acknowledges that, mentioning how coesite produced from quartz in some experiments cannot be well explained in terms of mean stress and citing Hirth and Tullis (1994). This was discussed in “Polymorphic transformations under stress” here but is part of a broader picture in which stress affects mineral reactions as well as (relatively simple) polymorphic transformations. 10s of km error in estimated burial depths can result from over and under-pressure, but 10s of km error in estimated burial depths can also result from modest applied stresses depending on the grain scale reaction pathways, according to Wheeler (2014). I emphasise that these are separate, distinct predictions.

-

Here, I discuss the effects of grain-scale stresses (regardless of the source of stress, whether it be tectonic or imposed in experiments) on reaction. I argue there is no equilibrium, and that mean stress does not have a central role in influencing reaction.

-

In work on tectonic overpressure, the focus is on large scale dynamic stress systems and how models predict mean stresses quite different to lithostatic. Mineral assemblages are then discussed based on a common assumption that there is in principle an equilibrium, and it is controlled by mean stress.

It will be useful, though not easy, to reconcile these predictions.

Reaction is a deformation mechanism

The idea that reaction is a deformation mechanism is implicit in many of the experiments that I describe here. Pressure solution (experiment type 3) and diffusion creep (4) are obviously deformation mechanisms but can also be thought of as reactions in which reactants and products have the same chemistry. Correns’s experiment (5) moves a weight and if such a system is confined (6) stress will build up with consequent elastic or inelastic deformation. Polymorphic transformation may involve a volume change in a particular direction—deformation again (7). More general solid-state reactions themselves may trigger surrounding deformation, but again are a deformation mechanism themselves (8). Even with a planar interface between olivine and quartz, one might expect the volume change to be manifest as shortening perpendicular to the reaction rim. What this implies is that, as numerical models are developed, it is to be expected that if stress terms appear in reaction rate, then reaction rate should appear in rheology.

An example of the importance of these issues is the proposal of Nakajima et al. (2013) that subducting plates, the volume changes involved in oceanic crust transforming to eclogite give rise to stresses which trigger earthquakes. The volume reduction in their model involves shortening in all directions and to accommodate this adjacent to mantle, which does not undergo densification, tensional stresses are generated in the crust. These are of the order of GPa (Kirby et al. 1996) so it would be useful to know how the stresses feedback on the eclogitisation reactions and the way in which the volume changes are manifest.

Future work

Ideas here could stimulate new ways of interpreting existing experiments, the design of new experiments and new ways of interpreting natural microstructures.

Numerical models are always required to allow extrapolation of experimental results. All the experiments discussed here show that the kinetics of reaction will influence observations, so need to be included in future detailed numerical models. I suggest the “reaction pathway” idea (Wheeler 2014) is useful here, though it is a simplified description of behaviour. Future grain-scale models should include local links between stress, chemistry and kinetics and quantitative description of larger-scale behaviour should emerge (reaction pathways would then form part of a simplified qualitative description of the quantitative behaviour). Grain scale models for diffusion creep are the best example of this idea. However, it is not trivial to extend such models: for example, there are mathematical difficulties in establishing precise models for bimineralic diffusion creep (Wheeler and Ford 2007). Experiments would assist in overcoming such problems, by illuminating the processes and kinetics involved. A key aspect of any grain-scale model is that stress will be heterogeneous on the grain scale. Stress is almost certainly non-uniform on some scale in the experiments discussed (Table 2), whether they be designed thus (Cionoiu et al. 2019; den Brok and Morel 2001) or whether it be intrinsic to a process such as grain scale stress variations due to elastic (Burnley and Zhang 2008) or diffusion creep responses (Wheeler and Ford 2007). Such variations need to be included in numerical models to enable interpretation of experiments with complicated geometries (including any polycrystal), and hence extrapolate those results to describe how stress and chemical processes interact in the Earth.

Conclusions

-

An equation relating chemical potential to normal stresses on crystalline interfaces and surfaces is broadly in accord with published analyses of eight diverse types of experiment that involve interactions of stress and chemical effects.

-

Where quantitative agreement is lacking, the equation is still used, directly or indirectly, to assist the explanation.

-

Because the equation relates to particular interfaces, there is the possibility of different reaction pathways with different affinities, depending on which interfaces are involved in the reaction. The overall behaviour of an experiment or natural system will depend on kinetics as well as the affinities of various reaction pathways. This idea may help to resolve the lack of quantitative agreement between the force of crystallisation experiments and theory—not all reaction pathways have been considered.

-

Large-scale predictions of how stress interacts with chemical processes, including reaction rates and rheology, need to be based on grain-scale models for those interactions. The equation highlighted here should be used in building such grain-scale models.

References

Aki K, Richards PG (2002) Quantitative seismology. University Science Books

Asaro RJ, Tiller WA (1972) Interface morphology development during stress-corrosion cracking.1 Via surface diffusion. Metall Trans 3:1789–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02642562

Becker GF, Day AL (1916) Note on the linear force of growing crystals. J Geol 24:313–333. https://doi.org/10.1086/622342

Bedford J, Fusseis F, Leclere H, Wheeler J, Faulkner D (2017) A new 4D view on the evolution of metamorphic dehydration reactions. Sci Rep 7:6881. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07160-5

Brodie KH, Rutter EH (1985) On the relationship between deformation and metamorphism, with special reference to the behaviour of basic rocks. In: Thompson AB, Rubie DC (eds) Metamorphic reactions: Kinetics, Textures and Deformation, vol 4. Advances in Physical Geochemistry. Springer-Verlag, Holland, pp 138–179

Burnley PC, Green HW (1989) Stress dependence of the mechanism of the olivine spinel transformation. Nature 338:753–756. https://doi.org/10.1038/338753a0