Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and co-existing psychiatric/psychological impairments as well as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are common among young offenders. Research on their associations is of major importance for early intervention and crime prevention. Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) warrants specific consideration in this regard. To gain sophisticated insights into the occurrence and associations of ADHD, IED, ACEs, and further psychiatric/psychological impairments in young (male and female) offenders, we used latent profile analysis (LPA) to empirically derive subtypes among 156 young offenders who were at an early stage of crime development based on their self-reported ADHD symptoms, and combined those with the presence of IED. We found four distinct ADHD subtypes that differed rather quantitatively than qualitatively (very low, low, moderate, and severe symptomatology). Additional IED, ACEs, and further internalizing and externalizing problems were found most frequently in the severe ADHD subtype. Furthermore, females were over-represented in the severe ADHD subtype. Finally, ACEs predicted high ADHD symptomatology with co-existing IED, but not without IED. Because ACEs were positively associated with the occurrence of ADHD/IED and ADHD is one important risk factor for on-going criminal behaviors, our findings highlight the need for early identification of ACEs and ADHD/IED in young offenders to identify those adolescents who are at increased risk for long-lasting criminal careers. Furthermore, they contribute to the debate about how to best conceptualize ADHD regarding further emotional and behavioral disturbances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Delinquency committed by adolescents and young adults is a common phenomenon; however, whereas most juveniles overcome offending when entering adulthood, some of them continue to develop long-lasting criminal careers [1]. With respect to their future perspectives, the economic costs, and the safety of our society, it is essential to identify young offenders who are at risk of continuous crime at an early stage of their criminal development.

Psychiatric impairments have been related to elevated risk of delinquency in young people: High rates of various psychiatric disorders were found among young detainees [2,3,4,5]. Although internalizing problems must not be neglected, externalizing problems are usually more prevalent [2]. Moreover, young offenders with high expressions of externalizing behavior problems carry an elevated risk of criminal recidivism compared to young people without or with low expressions of externalizing symptomatology [5,6,7,8].

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one externalizing disorder, which has received increased attention in research on juvenile and adult delinquency. Previous findings indicate that children with ADHD (with and without psychiatric comorbidity) show an elevated risk of early, persistent, and versatile crime involvement [9,10,11,12,13]. Meta-analyses point to ADHD prevalence rates of 26–30% within juvenile and adult detention samples, reflecting a five- to tenfold risk in comparison to the general population [14, 15]. Young detainees with ADHD showed faster and higher reoffending rates than those without ADHD [16]. Moreover, offenders with ADHD tend to be more frequently involved in impulsive-reactive violent activities than in proactive-premeditated criminality [17].

However, research on the association between ADHD and delinquency has faced several complications. There has been an ample debate about the conceptualization of ADHD. Sole reliance on an ADHD diagnosis risks to undermine specific differences among the three presentations (predominantly inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, or combined) described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [18]; yet, the empirical distinctiveness of these presentations has also been criticized [19,20,21]. Moreover, ADHD is often accompanied by further emotional and behavioral problems that are not represented by the given diagnostic criteria. There is an ongoing scientific debate whether such symptoms display characteristics of comorbid psychiatric disorders or constitute to the core symptomatology of ADHD [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Yet, the consideration of these symptoms is imperative when exploring the associations of ADHD with delinquency as they might affect further crime development [28, 29].

With regard to further examining emotional and behavioral problems accompanying ADHD, one psychiatric disorder appears of specific relevance: intermittent explosive disorder (IED). According to DSM-5 [18], IED reflects repeated acts of impulsive-aggressive outbursts (verbal or physical, against humans, animals or objects), which are clearly disproportionate to the given situation. Considering the simultaneous occurrence of ADHD and IED in young offenders is necessary taking into account the similarities of both disorders on a behavioral level and on underlying processes as well as their association with criminal behavior [23, 30, 31]. IED ranged among the most commonly reported disorders among adolescents in the US National Comorbidity Survey (14.1%), and both ADHD and IED were predictive for reported crime [32]. IED rates of 5–11% were found in juvenile and adult offender samples [33, 34]. DeLisi et al. [35] highlighted that “by its very definition, IED is an important clinical disorder with explicit linkages to criminal offending; however, the construct has been largely overlooked by researchers”. They found IED to be predictive of violent offending and persistent crime involvement and recommended to further investigate the distinct occurrence of IED in offender samples and not only consider respective symptomatology as affiliated to other behavioral disorders such as ADHD.

Additionally, neglecting shared etiological factors that contribute to ADHD, co-existing emotional/behavioral problems, and delinquency holds the risk to draw inadequate conclusions and implications. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) display such influencing factors. ACEs are common among young offenders and were proven to contribute to ADHD and the occurrence and maintenance of delinquency [3, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. ACEs were also associated with IED over and above their effects on other psychiatric disorders [45,46,47]. Research has proposed that the association of ACEs, ADHD, and IED with aggressive behavior may rely on distorted social cognition processes as a consequence of, e.g., dysfunctional social learning experiences [39, 48,49,50].

The present study intended to overcome some of the abovementioned shortcomings of previous research (e.g., categorical consideration of ADHD diagnosis or the neglect of co-occurring emotional/behavioral problems and shared risk factors such as ACEs). First, according to the dimensional character and heterogeneity of ADHD [16, 23, 51], we used latent profile analysis (LPA) to empirically derive mutually exclusive, homogeneous subtypes of ADHD in a juvenile detention sample. Similar approaches have been successfully used to examine the heterogeneity of (a) ADHD in non-forensic samples [52], and (b) adolescent delinquents regarding other disruptive behavior problems like oppositional defiant disorder [8] and conduct disorder [7], as well as ACEs [53]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet followed a latent class/profile approach to investigate subtypes of ADHD among young offenders. Second, we aimed at extending previous research by focusing on IED as a relevant representation of emotional/behavior problems co-occurring with ADHD. Since both ADHD and IED have been shown to co-exist with further psychiatric impairments [54,55,56,57,58], we also considered further internalizing and externalizing problems. Moreover, we accounted for the effects of ACEs in the associations of ADHD, IED and further internalizing and externalizing problems within young offenders. Furthermore, because our sample consisted of male and female offenders, we were able to investigate potential sex differences. Research on the associations of ADHD and crime in female offenders is rare and existing studies have so far yielded inconclusive results [4, 59]. Based on previous research, we expected to detect at least two subtypes of young offenders reflecting high and low expressions of ADHD. We anticipated higher rates of IED compared to general population samples, especially in co-occurrence with elevated ADHD severity. We assumed that participants high on ADHD and/or IED had increased rates of ACEs and showed further internalizing and externalizing problems more frequently. Due to the scarcity of research on ADHD in female offenders, we examined sex differences in exploratory manner.

Methods

Procedure

The present study was conducted as part of a pilot study that aimed to examine the feasibility of scientific data assessment in the below-mentioned juvenile detention center. The study protocol was approved by the ethical review board of the Medical Council in Rhineland-Palatine, Germany (reference number: 837.290.17 (11124); approval date: 21st September 2017). Study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data assessment took place at the juvenile detention center in Worms, Germany. The German juvenile law is usually applied for young people aged 14–21 years (at the time of offending); however, the maximum age may be expanded under specific circumstances (e.g., when several offences committed at different points in time (age periods) are summarized for one verdict). Juvenile detention is defined as an educational intervention for adolescents and young adults. In contrast, youth prison reflects a measure of punishment. Thus, juvenile detention is usually arranged for adolescents or young adults with rather minor offenses who have not yet been involved in chronic crime. The maximum duration of juvenile detention is 30 days. All adolescents and young adults who had to stay for at least 7 days in juvenile detention between May 2018 and May 2019 were provided study information via mail about three weeks before the beginning of sentence. There were no further inclusion or exclusion criteria. The document contained information about (1) study procedures, (2) the voluntariness of participation including the possibility to withdraw consent at any time, (3) the scientific purpose of data collection, (4) the anonymization of data, and (5) the fact that consent or denial of study participation would not have any consequences concerning the given sentence.

In case of study participation, written informed consent was given by the detainee (and his/her legal guardians when aged below 18 years) at the beginning of sentence. Self-report questionnaires were handed over on the first day of detention to be filled out at the detainees’ private detention rooms. Completing the questionnaires took about one hour. In case a participant did not understand the content of single items, she/he could ask a responsible staff member at the juvenile detention center for assistance. Completed questionnaires were collected in a closed box.

Participants

Since the present study represents (parts of) a pilot/feasibility study, we did not apply any sample size calculations in advance. Data were collected from a consecutive sample of a total of 161 adolescents or young adults (134 males, 27 females) with a mean age of 18.48 years (SD = 2.1; range = 14–25 years). For the present study, data were considered only from those detainees who had given full information on the questionnaires concerning ADHD and IED symptoms, leaving a total of 156 participants (129 male, 82.7%; 27 female, 17.3%) between 14 and 25 years (M = 18.53 years, SD = 2.13 years). The mean length of detention was 2.11 weeks (SD = 0.68 weeks, range = 1–4 weeks). Detainees showed an average school education of 9.29 years (SD = 0.75 years, range = 8–13 years). Males and females did not differ concerning age, length of detention, or years of education (p > 0.05).

Index offenses (most severe per participant) included (grievous) bodily harm (n = 34; 21.8%), property offenses (n = 56; 35.9%), breach of narcotics law (n = 26; 16.7%), breach of school law/excessive school skipping (n = 20; 12.8%), driving without driver`s license (n = 9; 5.8%), and others (n = 11; 7.1%). No sex differences were found, χ2(5) = 4.46, p = 0.485.

Questionnaires

Self-report Wender-Reimherr adult attention deficit disorder scale (SR-WRAADDS)

ADHD symptoms based on the Utah Criteria were assessed by the German version of the SR-WRAADDS (WR-SB) [51, 60, 61], which comprises 59 items evaluated on a five-point Likert-scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much). Items were summed up to 10 scales: (1) attention difficulties, (2) hyperactivity/restlessness, (3) temper, (4) affective lability, (5) emotional over-reactivity, (6) disorganization, (7) impulsivity, (8) oppositional symptoms, (9) academic problems, and (10) social attitude.

Satisfactory psychometric properties were proven for the English and German versions of the WR-SB [51, 60]. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for all subscales were between 0.77 and 0.90.

Intermittent explosive disorder-screening questionnaire for DSM-5 (IED-SQ)

IED was assessed using the IED-SQ [62]. The IED-SQ consists of two parts. Part 1 contains five items relating to the frequency of aggressive behaviors on a six-point Likert-scale (0 = never happened to 5 = happened “so many” times that I cannot give a number) that can be summed up to an IED total aggression score. Part 2 contains five items asking for additional aggression-related behaviors, namely (1) weekly arguments/temper outbursts, (2) annual number of aggression against people or property, (3) planned or unplanned aggression, (4) concern about/problems because of aggression, and (5) aggression without the influence of any substances. Indication of DSM-5 IED is based on a combination of an IED total aggression score of at least 12 and the fulfillment of part 2 items according to given scoring criteria (please consider to the given references for detailed scoring information). For the present study, the IED-SQ was translated into German by the shared first author and independently back-translated into English by two German master’s degree psychologists who were fluent in English and blind to the original IED-SQ. Back-translations were compared to the original IED-SQ by an English native speaker.

Good psychometric properties were proven for the IED-SQ, e.g., regarding the accordance with clinical diagnoses (к = 0.80), test–retest reliability (к = 0.71), 82% sensitivity, 97% specificity, and overall accuracy = 0.90 [62]. In the present study, internal consistency of the IED total aggression score was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Childhood trauma questionnaire-short form (CTQ-SF)

The German version of the 28-item CTQ-SF [63, 64] was used to assess ACEs in form of emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse, physical neglect, and sexual abuse occurred between the ages of 0 to 18 years. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert-scale from 0 (= never true) to 4 (= very often true). A CTQ-poly score was calculated to represent poly-victimization following a procedure applied in previous studies [42, 65]. First, items rated as 0 and 1 were coded as not present and items rated as 2 to 4 were coded as present. Second, CTQ-subscales were rated as fulfilled if one respective item was coded as present. Third, a CTQ-poly score was built by summing up the number of fulfilled subscales.

The English and German CTQ-(SF) showed good psychometric properties [63, 64, 66]. In the present study, internal consistencies for the subscales were between Cronbach’s α = 0.64 (physical neglect) and α = 0.96 (emotional neglect).

Youth self-report (YSR)

Perceived impairments during the last six months were assessed using the 103-item YSR [67, 68]. The occurrence of each item is rated as 0 (= never), 1 (= sometimes), or 2 (= always). Items can be assigned to eight subscales, which build up to three problem scales: (1) internalizing problems (withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, anxious/depressed; (2) externalizing problems (rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior); and (3) mixed problems (thought problems, attention problems, social problems). Clinical significance is present when scale scores exceed certain T-values provided in the manual. For the present study, internalizing and externalizing problem scales were considered.

The German version of the YSR showed satisfactory psychometric properties [68]. Internal consistency was good in the present study (internalizing problems: Cronbach’s α = 0.77; externalizing problems: Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS version 26.0 for Windows and in R (R Core Team, 2020). Person-centered ADHD subtypes were empirically derived by latent profile analysis (LPA) using the tidyLPA package in R [69]. The ten WR-SB scale scores served as indicators. The best fitting model was selected under consideration of several fit indices (see below). Participants were assigned to latent profiles according to their highest affiliation probability based on maximum likelihood estimations. To compare ADHD subtypes regarding further variables, we performed parametric and non-parametric analyses, e.g., χ2-statistics, ANOVAs, and MANOVAs with post-hoc Bonferroni or Games–Howell tests as well as linear and multinomial logistic regressions. Results were considered as statistically significant with p-values below 0.05.

Results

LPA on ADHD symptomatology

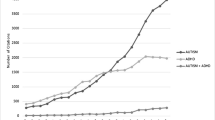

Models with one to ten profiles were compared using a hierarchical analytical process provided by the tidyLPA command in R [70], which includes several fit indices, e.g., the Akaike Information Criterion [71], Approximate Weight of Evidence Criterion [72], Bayesian Information Criterion [73], Classification Likelihood Criterion [74], and Kullback Information Criterion [75]. The model with four latent profiles fitted our data best. The entropy value of 0.93 indicated clear assignments of participants to latent ADHD profiles [76]. Profiles are presented in Fig. 1 (based on standardized z-values). According to their differences on overall ADHD severity, we labeled them (1) very low, (2) low, (3) moderate, and (4) severe ADHD subtypes.

Descriptive differences among subtypes

Descriptive data of LPA derived subtypes are presented in Table 1. Male participants were over-represented in the low ADHD subtype, females were over-represented in the severe subtype. Participants of the severe subtype were significantly older than those of the low ADHD subtype. No differences emerged regarding index offenses, length of detention, or years of education.

Subtypes differed significantly among each other in ascending order (very low, low, moderate, severe ADHD) on the WR-SB scales attention difficulties, affective lability, emotional over-reactivity, disorganization, and oppositional symptoms. Significant overall differences were also found on all other WR-SB subscales showing increasing values with elevated ADHD severity; yet, not all subtypes differed significantly from each other.

IED total aggression scores increased with elevated ADHD severity. The very low ADHD subtype differed significantly from the moderate and severe subtype, and the low subtype differed significantly from the severe subtype. A total of 56 participants (35.90%) fulfilled the criteria for DSM-5 IED diagnosis. Participants with IED diagnosis were over-represented in the severe ADHD subtype and under-represented in the low and very low subtypes.

Regarding the CTQ-SF, 85.3% of the total sample reported at least one ACE. More specifically, 18 participants (11.5%) reported one ACE, 31 (19.9%) reported two ACEs, 40 (25.6%) reported three ACEs, 41 (26.3%) reported four ACEs, and 3 (1.9%) reported five ACEs. The mean CTQ-poly score was 2.43 (SD = 1.42). No sex differences were found (p = 0.212). ADHD subtypes differed significantly on CTQ-poly scores. The severe ADHD subtype showed the highest score with significantly more ACEs than the low subtype.

According to the YSR, 19.9% (n = 31) and 32.1% (n = 50) of the total sample showed clinically significant scores on internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively. No sex differences emerged for internalizing problems, but females were over-represented among those with clinically significant externalizing problems (n = 14, 51.9%, AR = 2.4), χ2(1) = 5.88, p = 0.015. Participants from the moderate and severe ADHD subtypes showed clinically significant internalizing and externalizing problems more frequently than other participants. ADHD subtype differences were also found on dimensional internalizing and externalizing problem scores. Scores of the very low and low ADHD subtypes were significantly lower than scores of the moderate and severe subtypes.

Associations among ADHD subtypes with and without comorbid IED, ACEs, and internalizing/externalizing problems

For further analyses, we built combined groups according to ADHD severity and IED diagnoses. To guarantee sufficient subsample sizes and to account for the similarities of the very low and low ADHD subtypes as well as the moderate and severe ADHD subtypes, we combined the very low and low subtype to one group called lowADHD, and the moderate and severe subtype to one group called highADHD, resulting in two equally proportioned ADHD groups (each 50% of all participants). Combined with IED diagnoses, four groups were built: (1) lowADHD−IED (n = 67, 42.9%), (2) lowADHD+IED (n = 11, 7.1%), (3) highADHD−IED (n = 33, 21.2%), and (4) highADHD+IED (n = 45, 28.8%). Table 2 presents descriptive results concerning these groups. No differences were found for age, length of detention, years of education, or offenses. Female participants were under-represented in the lowADHD−IED group but over-represented in the highADHD+IED group. The highADHD+IED group showed a significantly higher CTQ-poly score than the lowADHD−IED group. Regarding YSR, participants with clinically significant internalizing problems were over-represented in the highADHD−IED group and under-represented in the lowADHD−IED group. Participants with clinically significant externalizing problems were over-represented in the highADHD+IED group and under-represented in the lowADHD−IED group. Internalizing problem scores of the lowADHD−IED group were significantly lower than scores of the highADHD−IED and highADHD+IED groups, and scores of the lowADHD+IED group were lower than scores of the highADHD−IED group. For externalizing problems, the highADHD+IED group showed the highest scores, followed by those of the highADHD−IED group. Both were significantly higher than scores of the lowADHD−IED group.

Results of regression analyses are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Using different models, we found that (1) the CTQ-poly score significantly predicted belonging to the ADHD+IED but not to the ADHD−IED group and (2) high YSR internalizing and externalizing problem scores. Moreover, highADHD+IED and highADHD−IED groups (3) significantly predicted internalizing and externalizing problem scores with stronger effects of the ADHD−IED group on internalizing problems, and the ADHD+IED group on externalizing problems. (4) CTQ-poly score and affiliations to highADHD+IED/highADHD−IED groups maintained their predictive effects on internalizing and externalizing problems even when considered simultaneously. Furthermore, predictive effects of sex over and above those of CTQ-poly scores were found as females showed higher risk of belonging to high ADHD groups and of internalizing problems.

Discussion

This study is the first to explore the occurrence of empirically derived ADHD-subtypes with and without co-existing IED as well as their relations to ACEs and further internalizing and externalizing problems among young offenders. Considering the major relevance of these factors for understanding the occurrence and maintenance of criminal behaviors, our examination of a sample of young offenders at an early stage of criminal development yielded several important findings that expand current knowledge in this field.

Four empirically based ADHD subtypes emerged. They differed on overall severity instead of showing varying symptom patterns, reflecting differences of rather quantitative than qualitative nature. ADHD symptoms were highly prevalent with a quarter of participants reporting at least moderate and one quarter reporting severe ADHD symptomatology. These results are in line with previous findings of high ADHD rates in young and adult offenders and underscore the importance to consider ADHD as a relevant psychiatric disorder in forensic samples [14, 77]. In addition, our results support calls not only to rely on categorical presentations of ADHD but to consider dimensional expressions of ADHD symptomatology/severity [23, 51]. Retz-Junginger and colleagues [51] compared young male detainees with and without ADHD diagnoses on seven of the 10 WR-SB scales and found similar patterns to those found on the subtypes in the present study. Compared to prior studies that have implemented LCA/LPA approaches on ADHD symptomatology [27, 52], we found fewer distinct subtypes, which might be ascribed to the specific composition of our young offender sample in contrast to more general populations as well as the fact that we did not include further co-existing emotional or behavioral symptoms in our LPA. However, the ADHD subtypes found in the present study were more distinguishable than expected, although some differences on further variables of interest were subtle and thus allowed to merge the four subtypes into two groups representing low and high ADHD severity.

A substantial prevalence of DSM-5 oriented IED (36%) was found in the present sample compared to rates reported in general population, psychiatric patient, or other offender samples [34, 35, 57, 78]. This finding indicates that IED is common among young offenders and merits more scientific consideration. However, it is possible that the prevalence found in the present study might be over-estimated at least to some extent due to bias in self-report in contrast to external clinical judgment. Yet, reliance on DSM-5 has been proposed to lead to a higher IED prevalence than earlier considerations of DSM-IV criteria [78]. In addition, young offenders in the present study showed elevated rates of further internalizing and externalizing problems; as found in previous research, externalizing problems reached clinical significance more often than internalizing problems, whereas the latter was still common, highlighting the necessity not to neglect those impairments in offender samples [2].

Our results also underline that the vast majority of young offenders is burdened with ACEs [3, 44]. More than 85% of participants reported at least one of the five assessed ACEs, and more than 28% indicated to have experienced at least four out of five ACE categories. Thus, high rates of ACEs are present in intensive and chronic young offenders [43] but also in those delinquents who are rather at an early stage of criminal development.

Regarding the associations among ADHD, IED, ACEs and further internalizing and externalizing problems, the following results require specific consideration. First, IED was particularly prevalent among participants with severe ADHD. This finding is consistent with research emphasizing the common co-existence of ADHD and IED (and other externalizing disorders) both on behavioral outcomes as well as underlying processes [23, 30, 31]. In their literature review, Gnanavel and colleagues [23] point to similarities in symptomatology (e.g. regarding aggressive and impulsive behavior) und highlight shared genetic as well as environmental risk factors, the latter including disturbed family contexts. Puiu et al. [30] refer to shared associations with emotional lability and irritability as well as comparable expressions of deficient emotion regulation in terms of, e.g., hyperarousal, intrusiveness, or distractibility. Yet, they point out that impulsive aggression of IED subjects appeared to be of greater severity compared to individuals with ADHD or other externalizing disorders. It has been proposed that the intensity of aggression in IED may be traced back to repeated experience of interpersonal ACEs, which contributed to a seriously disturbed development of emotion regulation abilities [46]. Although we are not aware of any previous study that had directly compared differences in the associations of ACEs with ADHD and IED subjects, our findings indicate that an elevated ACE history may increase the risk of IED when co-occurring with elevated ADHD symptomatology. Thus, one could assume that ADHD and IED share etiological and symptomatic factors related to emotional dysregulation, but ACEs intensify problematic outcomes in terms of (severe and impulsive) aggressive behavior. Future research should examine this assumption in more detail. Young offenders high on ADHD with or without IED were, however, not more likely to be detained for violent offenses than other participants. Yet, findings must be interpreted cautiously, because information was available only on the index offenses and not on further/previous crimes. Furthermore, young offenders with severe violent offenses are probably more likely to be found in prison populations than in juvenile detention.

Second, high ADHD severity was related to elevated rates of further internalizing and externalizing problems, highlighting the multiplicity of psychiatric impairments accompanying ADHD [51]. Under consideration of co-existing IED, those participants high on ADHD with IED showed comparably high expressions of externalizing problems, whereas those high on ADHD without IED stood out because of an elevated risk of internalizing problems. Thus, regarding further psychiatric impairments, it appears of major importance not only to consider ADHD but also co-existing IED symptoms. Concerning the debate of the conceptualization of ADHD with and without further emotional and behavioral symptoms [22, 79,80,81], the co-existence of both disorders in the present sample hints to overlapping features of ADHD (subtypes) and IED-typical presentations of emotional dysregulation, whereas the specific associations with other variables of interest indicate the distinctiveness of both disorders that rather appear to co-exist in the form of (subtype-dependent) comorbidity.

Third, high ADHD severity was related to increased ACE rates. The cumulative ACE score predicted severe ADHD, but only when co-existent with IED. Previous research has yielded different findings concerning the link between ACEs and ADHD. For example, some studies did not find predictive links between ACEs and ADHD [3], whereas others did [40] and others highlighted the role of co-occurring emotional and/or behavioral disturbances in this context [38, 82]. The present findings support the latter and indicate that considering ADHD without the psychosocial background might hinder the detection and development of explanatory approaches with respect to psychiatric burden in young offenders. In addition, cumulated ACEs positively predicted both internalizing and externalizing problems beyond the abovementioned effects of ADHD, pointing to the independent influences of ACEs and ADHD on further psychiatric impairment.

Fourth, the explanatory examination of sex differences indicated that young female offenders were more likely to show severe ADHD with or without IED as well as further behavior problems, whereas no differences were found regarding cumulative ACE burden. These findings are only partially consistent with prior studies. Some researchers reported that ADHD is common in young female detainees [59], whereas others found lower rates of ADHD in young female compared to male offenders [4]. It has been suggested that it requires more severe and frequent criminal behavior for females to get arrested, resulting in an over-representation of severely disturbed young females within forensic samples, most of them with elevated trauma histories [4].

Some qualifications must be considered for the interpretation of the present findings. Due to the primary purpose as pilot/feasibility study, data was solely assessed by self-reports and not expanded to external evaluation (e.g., interviewing) by clinical experts. The validity of self-reports on ADHD symptoms, further psychiatric impairments, and ACEs has been debated, especially in forensic samples [2, 6, 83]. We could not ensure that the young offenders’ educational levels might have affected comprehension of the questionnaires; however, as participants had experiences at least 8 years of school education, we were confident that the majority of young offenders comprehended respective items, and there was also the possibility for participants to ask staff members in case of uncertainties in item comprehension. Additionally, the application of more objective, physiological measures (e.g., electroencephalography (EEG) [31]) would have been interesting but was beyond the scope of the present study. Furthermore, we only assessed five types of ACEs, although previous research on young offenders has yielded interesting findings by including more types of both intra-familial and extra-familial ACEs [53]. We were not able to include data on former crime and re-offending or further biographical information, which are of major importance for the understanding of criminal development. Moreover, the size of the current sample was limited and only contained a small number of female subjects, requiring cautious interpretation and prohibiting generalized implications, particularly regarding sex-differences. A larger sample size would have led to greater statistical power and, thus, to more confidence regarding the interpretation of our results. Eventually, testing multiple hypotheses on one sample has been associated with the risk of type-I error inflation, and the benefits and disadvantages of applying respective correction methods have been subject to scientific debate [84]. For the present study, we decided to consider results with p-values below the general α-level of 0.05 as statistically significant, yet recommending cautious interpretation and suggesting that conclusions with higher reliability may be drawn from results with p-values of and below 0.001. However, we assessed a set of important criminogenic variables in a non-preselected sample of young offenders who were at an early stage of criminal development and who had shown a variety of (rather minor) offenses. These offenders represent a high-risk population for chronic crime as it occurs in real life settings. Thus, our findings are of special importance for developing (1) adequate measures aimed at keeping young offenders from continuing criminal behavior and (2) primary prevention strategies to preclude the occurrence of juvenile criminal conduct in the first place. In addition, we used sophisticated data analysis techniques to derive ADHD subtypes based on empirical rather than theoretical foundation which allowed the “depiction of the way these [young offenders] are naturally sorted” [27]. Furthermore, focusing on the role of IED in forensic samples has been claimed to be of major importance [35].

In conclusion, the present study showed that not only chronic and severe criminals but also young offenders at the beginning of their delinquent development are afflicted with ADHD, IED, ACEs, and further internalizing and externalizing problems. Our findings highlight the need for early identification of crime-promoting factors in young offenders, which requires standardized but individualized assessment of the young offenders’ (or high-risk samples’) risks and needs by psychiatrically/psychologically educated experts. Practitioners in psychiatry, psychology, and law enforcement as well as politicians and other stakeholders need to work together towards the realization and implementation of tailored interventions, not only to protect society from future crime and reduce respective economic costs, but also to allow young offenders and high-risk youths to develop functional and crime-free future prospects.

Change history

20 July 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-021-01308-1

References

Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701

Colins O, Vermeiren R, Vreugdenhil C et al (2010) Psychiatric disorders in detained male adolescents: a systematic literature review. Can J Psychiatr 55:255–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005500409

Bielas H, Barra S, Skrivanek C et al (2016) The associations of cumulative adverse childhood experiences and irritability with mental disorders in detained male adolescent offenders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0122-7

Plattner B, Aebi M, Steinhausen H-C, Bessler C (2011) Psychopathologische und komorbide Störungen inhaftierter Jugendlicher in Österreich. Z Kinder- Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 39:231–242. https://doi.org/10.1024/1422-4917/a000113

Bessler C, Stiefel D, Barra S, Plattner B, Aebi M (2019) Mental disorders and criminal recidivism in male juvenile prisoners. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. https://doi.org/10.1024/1422-4917/a000612

Wibbelink CJM, Hoeve M, Stams GJJM, Oort FJ (2017) A meta-analysis of the association between mental disorders and juvenile recidivism. Aggress Violent Behav 33:78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.005

Aebi M, Barra S, Bessler C, Walitza S, Plattner B (2019) The validity of conduct disorder symptom profiles in high-risk male youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01339-z

Aebi M, Barra S, Bessler C, Steinhausen H-C, Walitza S, Plattner B (2016) Oppositional defiant disorder dimensions and subtypes among detained male adolescent offenders. J Child Psychol Psychiatr Allied Discip. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12473

Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Biswas A, MacLean MG, Babinski DE, Karch KM (2011) The delinquency outcomes of boys with ADHD with and without comorbidity. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39:21–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9443-9

Mohr-Jensen C, Steinhausen H-C (2016) A meta-analysis and systematic review of the risks associated with childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on long-term outcome of arrests, convictions, and incarcerations. Clin Psychol Rev 48:32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.002

Dalsgaard S, Mortensen PB, Frydenberg M, Thomsen PH (2013) Long-term criminal outcome of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Crim Behav Ment Heal 23:86–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1860

Fletcher J, Wolfe B (2009) Long-term consequences of childhood ADHD on criminal activities. J Ment Health Policy Econ 12:119

Retz W, Rösler M (2009) The relation of ADHD and violent aggression: What can we learn from epidemiological and genetic studies? Int J Law Psychiatr 32:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.04.006

Baggio S, Fructuoso A, Guimaraes M, Fois E, Golay D, Heller P, Perroud N, Aubry C, Young S, Delessert D (2018) Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in detention settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatr 9:331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00331

Young S, Moss D, Sedgwick O, Fridman M, Hodgkins P (2015) A meta-analysis of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in incarcerated populations. Psychol Med 45:247–258. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000762

Philipp-Wiegmann F, Rösler M, Clasen O, Zinnow T, Retz-Junginger P, Retz W (2018) ADHD modulates the course of delinquency: a 15-year follow-up study of young incarcerated man. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 268:391–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-017-0816-8

Retz W, Rösler M (2010) Association of ADHD with reactive and proactive violent behavior in a forensic population. ADHD Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord 2:195–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-010-0037-8

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC

Baeyens D, Roeyers H, Vande WJ (2006) Subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): distinct or related disorders across measurement levels? Child Psychiatr Hum Dev 36:403–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-006-0011-z

Power TJ, Costigan TE, Eiraldi RB, Leff SS (2004) Variations in anxiety and depression as a function of ADHD subtypes defined by DSM-IV: do subtype differences exist or not? J Abnorm Child Psychol 32:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jacp.0000007578.30863.93

Cahill BS, Coolidge FL, Segal DL, Klebe KJ, Marle PD, Overmann KA (2012) Prevalence of ADHD and its subtypes in male and female adult prison inmates. Behav Sci Law 30:154–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2004

Faraone SV, Rostain AL, Blader J, Busch B, Childress AC, Connor DF, Newcorn JH (2019) Practitioner review: emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder–implications for clinical recognition and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 60:133–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12899

Gnanavel S, Sharma P, Kaushal P, Hussain S (2019) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: a review of literature. World J Clin Cases 7:2420. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2420

Biederman J, DiSalvo M, Woodworth KY, Fried R, Uchida M, Biederman I, Spencer TJ, Surman C, Faraone SV (2020) Toward operationalizing deficient emotional self-regulation in newly referred adults with ADHD: a receiver operator characteristic curve analysis. Eur Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.11

Reimherr FW, Roesler M, Marchant BK, Gift TE, Retz W, Philipp-Wiegmann F, Reimherr ML (2020) Types of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a replication analysis. J Clin Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19m13077

Beheshti A, Chavanon M-L, Christiansen H (2020) Emotion dysregulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatr 20:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2442-7

Ostrander R, Herman K, Sikorski J, Mascendaro P, Lambert S (2008) Patterns of psychopathology in children with ADHD: a latent profile analysis. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 37:833–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802359668

Storebø OJ, Simonsen E (2016) The association between ADHD and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) a review. J Atten Disord 20:815–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713512150

Thompson LL, Riggs PD, Mikulich SK, Crowley TJ (1996) Contribution of ADHD symptoms to substance problems and delinquency in conduct-disordered adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 24:325–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01441634

Puiu AA, Wudarczyk O, Goerlich KS, Votinov M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Turetsky B, Konrad K (2018) Impulsive aggression and response inhibition in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavioral disorders: findings from a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 90:231–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.016

Koelsch S, Sammler D, Jentschke S, Siebel WA (2008) EEG correlates of moderate intermittent explosive disorder. Clin Neurophysiol 119:151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2007.09.131

Coker KL, Smith PH, Westphal A, Zonana HV, McKee SA (2014) Crime and psychiatric disorders among youth in the US population: an analysis of the national comorbidity survey–adolescent supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 53:888–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.05.007

Mundt AP, Alvarado R, Fritsch R, Poblete C, Villagra C, Kastner S, Priebe S (2013) Prevalence rates of mental disorders in Chilean prisons. PLoS ONE 8:e69109–e69109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069109

Shao Y, Qiao Y, Xie B, Zhou M (2019) Intermittent explosive disorder in male juvenile delinquents in China. Front Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00485

DeLisi M, Elbert M, Caropreso D, Tahja K, Heinrichs T, Drury A (2017) Criminally explosive: intermittent explosive disorder, criminal careers, and psychopathology among federal correctional clients. Int J Forensic Ment Health 16:293–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2017.1365782

Björkenstam E, Björkenstam C, Jablonska B, Kosidou K (2018) Cumulative exposure to childhood adversity, and treated attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a cohort study of 543,650 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. Psychol Med 48:498–507. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001933

Fuller-Thomson E, Lewis DA (2015) The relationship between early adversities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Abuse Negl 47:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.005

Briscoe-Smith AM, Hinshaw SP (2006) Linkages between child abuse and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls: behavioral and social correlates. Child Abuse Negl 30:1239–1255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.008

Fuller-Thomson E, Mehta R, Valeo A (2014) Establishing a link between attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and childhood physical abuse. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma 23:188–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2014.873510

Ouyang L, Fang X, Mercy J, Perou R, Grosse SD (2008) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and child maltreatment: a population-based study. J Pediatr 153:851–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.06.002

De Sanctis VA, Nomura Y, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM (2012) Childhood maltreatment and conduct disorder: independent predictors of criminal outcomes in ADHD youth. Child Abuse Negl 36:782–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.003

Rucklidge JJ, Brown DL, Crawford S, Kaplan BJ (2006) Retrospective reports of childhood trauma in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 9:631–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054705283892

Fox BH, Perez N, Cass E, Baglivio MT, Epps N (2015) Trauma changes everything: examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and serious, violent and chronic juvenile offenders. Child Abuse Negl 46:163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.011

Baglivio MT, Epps N, Swartz K, Huq MS, Sheer A, Hardt NS (2014) The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. J Juv Justice 3. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/Prevalence_of_ACE.pdf

Fernandez E, Johnson SL (2016) Anger in psychological disorders: Prevalence, presentation, etiology and prognostic implications. Clin Psychol Rev 46:124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.012

Nickerson A, Aderka IM, Bryant RA, Hofmann SG (2012) The relationship between childhood exposure to trauma and intermittent explosive disorder. Psychiatr Res 197:128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.012

Lee R, Meyerhoff J, Coccaro EF (2014) Intermittent explosive disorder and aversive parental care. Psychiatr Res 220:477–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.059

Teisl M, Cicchetti D (2008) Physical abuse, cognitive and emotional processes, and aggressive/disruptive behavior problems. Soc Dev 17:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00412.x

Coccaro EF, Fanning JR, Keedy SK, Lee RJ (2016) Social cognition in intermittent explosive disorder and aggression. J Psychiatr Res 83:140–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.010

McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E (2012) The link between child abuse and psychopathology: a review of neurobiological and genetic research. J R Soc Med 105:151–156. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110222

Retz-Junginger P, Giesen L, Philipp-Wiegmann F, Rösler M, Retz W (2017) Der Wender-Reimherr-Selbstbeurteilungsfragebogen zur adulten ADHS. Nervenarzt 88:797–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-016-0110-4

Acosta MT, Castellanos FX, Bolton KL, Balog JZ, Eagen P, Nee L, Jones J, Palacio L, Sarampote C, Russell HF (2008) Latent class subtyping of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid conditions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 47:797–807. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318173f70b

Barra S, Bessler C, Landolt MA, Aebi M (2018) Patterns of adverse childhood experiences in juveniles who sexually offended. Sex Abus J Res Treat. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063217697135

Coccaro EF (2019) Psychiatric comorbidity in intermittent explosive disorder. In: Intermittent explosive disorder. Elsevier, pp 67–84

Essau CA, de la Torre-Luque A (2019) Comorbidity profile of mental disorders among adolescents: a latent class analysis. Psychiatr Res 278:228–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.007

Galbraith T, Carliner H, Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, McCloskey MS, Heimberg RG (2018) The co-occurrence and correlates of anxiety disorders among adolescents with intermittent explosive disorder. Aggress Behav 44:581–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21783

McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2012) Intermittent explosive disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatr 69:1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.592

Retz W, Retz-Junginger P, Hengesch G, Schneider M, Thome J, Pajonk F-G, Salahi-Disfan A, Rees O, Wender PH, Rösler M (2004) Psychometric and psychopathological characterization of young male prison inmates with and without attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 254:201–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-004-0470-9

Rösler M, Retz W, Yaqoobi K et al (2009) Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in female offenders: prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial implications. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 259:98–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-008-0841-8

Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, Wender PH, Gift TE (2015) Psychometric properties of the Self-report Wender-Reimherr adult attention deficit disorder scale. Ann Clin Psychiatr Off J Am Acad Clin Psychiatr 27:267–277

Wender P (1998) Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am 21:761–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70039-3

Coccaro EF, Berman M, McCloskey MS (2017) Development of a screening questionnaire for DSM-5 intermittent explosive disorder (IED-SQ). Compr Psychiatr 74:21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.12.004

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W (2003) Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus Negl 27:169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Mensebach C, Grabe H, Hill A, Gast U, Schlosser N, Höpp H, Beblo T, Driessen M (2010) Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): Erste Befunde zu den psychometrischen Kennwerten. PPmP-Psychother Psychosom Medizinische Psychol 60:442–450. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1253494

Aebi M, Linhart S, Thun-Hohenstein L, Bessler C, Steinhausen HC, Plattner B (2015) Detained male adolescent offender’s emotional, physical and sexual maltreatment profiles and their associations to psychiatric disorders and criminal behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43:999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9961-y

Karos K, Niederstrasser N, Abidi L, Bernstein DP, Bader K (2014) Factor structure, reliability, and known groups validity of the German version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Short-Form) in Swiss patients and non-patients. J Child Sex Abus 23:418–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.896840

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS (1987) Manual for the youth self-report and profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington

Döpfner M, Melchers P, Fegert J, Lehmkuhl G, Lehmkuhl U, Schmeck K, Poustka F (1994) Deutschsprachige Konsensus-Versionen der Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 4–18), der Teacher Report Form (TRF) und der Youth Self Report Form (YSR). Kindheit Entwicklung 3:54–59

Rosenberg J, Beymer P, Anderson D, van Lissa CJ, Schmidt J (2019) tidyLPA: an R package to easily carry out latent profile analysis (LPA) using open-source or commercial software. J Open Source Softw 4:978

Akogul S, Erisoglu M (2017) An approach for determining the number of clusters in a model-based cluster analysis. Entropy 19:452. https://doi.org/10.3390/e19090452

Akaike H (1974) A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 19:716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

Banfield JD, Raftery AE (1993) Model-based Gaussian and non-Gaussian clustering. Biometrics. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532201

Schwarz G (1978) Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 6:461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

Biernacki C, Govaert G (1997) Using the classification likelihood to choose the number of clusters. Comput Sci Stat 1997:451–457

Cavanaugh JE (1999) A large-sample model selection criterion based on Kullback’s symmetric divergence. Stat Probab Lett 42:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7152(98)00200-4

Clark SL, Muthén B (2009) Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf

Sebastian A, Retz W, Tüscher O, Turner D (2019) Violent offending in borderline personality disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropharmacology 156:107565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.008

Gelegen V, Tamam L (2018) Prevalence and clinical correlates of intermittent explosive disorder in Turkish psychiatric outpatients. Compr Psychiatr 83:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.03.003

Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E (2014) Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatr 171:276–293. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070966

Hirsch O, Chavanon ML, Christiansen H (2019) Emotional dysregulation subgroups in patients with adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a cluster analytic approach. Sci Rep 9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42018-y

Retz W, Stieglitz R-D, Corbisiero S et al (2012) Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD: what is the empirical evidence? Expert Rev Neurother 12:1241–1251. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.12.109

Ferrer M, Andión Ó, Calvo N, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Prat M, Corrales M, Casas M (2017) Differences in the association between childhood trauma history and borderline personality disorder or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnoses in adulthood. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 267:541–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-016-0733-2

Hardt J, Rutter M (2004) Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 45:260–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

Nakagawa S (2004) A farewell to Bonferroni: the problems of low statistical power and publication bias. Behav Ecol 15:1044–1045. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arh107

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethical review board of the Medical Council in Rhineland-Palatine, Germany (reference number: 837.290.17 (11124); approval date: 21st September 2017). Study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was given by each participant (and his/her legal guardians when aged below 18 years) before participation.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barra, S., Turner, D., Müller, M. et al. ADHD symptom profiles, intermittent explosive disorder, adverse childhood experiences, and internalizing/externalizing problems in young offenders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 272, 257–269 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01181-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01181-4