Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this survey was to assess medical students’ opinions about online learning programs and their preferences for specific teaching formats during COVID 19 pandemic.

Methods

Between May and July 2020, medical students who took an online gynecology and obstetrics course were asked to fill in a questionnaire anonymously. The questionnaire solicited their opinions about the course, the teaching formats used (online lectures, video tutorials featuring real patient scenarios, and online practical skills training), and digital learning in general.

Results

Of 103 students, 98 (95%) submitted questionnaires that were included in the analysis. 84 (86%) students had no problem with the online course and 70 (72%) desired more online teaching in the future. 37 (38%) respondents preferred online to traditional lectures. 72 (74%) students missed learning with real patients. All digital teaching formats received good and excellent ratings from > 80% of the students.

Conclusion

The survey results show medical students’ broad acceptance of the online course during COVID 19 pandemic and indicates that digital learning options can partially replace conventional face-to-face teaching. For content taught by lecture, online teaching might be an alternative or complement to traditional education. However, bedside-teaching remains a key pillar of medical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has posed challenges for medical education facilities, with the need to shift rapidly from the usual face-to-face teaching to online learning as routines in hospitals and medical schools have been interrupted by COVID-19 lockdown [1, 2]. Digital learning platforms like AMBOSS have been established in the past few years in German medical schools and universities and expand traditional teaching with digital options [3, 4]. Nevertheless, digital learning options provided by medical schools itself only took a minor part in students education due to the lack of infrastructure and technology at universities and negative attitudes among educators [5, 6]. Most digital learning studies conducted before the coronavirus outbreak had theoretical foci and demonstrated how such learning can improve students’ knowledge in domains such as communication skills [7, 8]. Data on medical students’ attitudes toward online education in clinical specialties, such as internal medicine, surgery, and gynecology, and techniques for the digital teaching of practical skills and examination administration, are sparse. The present survey-based study was conducted to assess medical students’ opinions about and attitudes toward online learning programs, and to identify their digital teaching format preferences.

Materials and methods

Setting and participants

The survey was conducted among medical students in the fifth clinical semester who completed a digital course between May and July 2020 at the Department of Gynecology, Obstetrics and Reproductive Medicine, Saarland University Hospital, Homburg/Saar, Germany. Regarding the level of familiarity with online teaching, students had access to the online learning platforms (e.g., AMBOSS) since 2018, but had no further experience with online teaching. The 5-day online course that took 3 h daily replaced a practical course in gynecology and obstetrics and was administered using different digital education formats: online lectures in gynecology and obstetrics, including live presentations on the main gynecological and obstetric diseases; video tutorials featuring real patient scenarios on topics such as vaginal delivery and caesarian section; and online education in gynecological examination and practical skills (e.g., cardiotocography).

After completing the course, students were invited to fill in a written questionnaire anonymously. The obtained questionnaires were stored at the hospital’s Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Questionnaire data and those on respondents’ gender and age, extracted from their course registration files, were entered into an SPSS (version 19; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) database.

Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was used to investigate medical students’ opinions about digital learning in the context of the gynecological curriculum, and their attitudes toward different online teaching formats. It was adapted in 2020 for digital course evaluation from a standardized questionnaire developed by medical educators at our hospital for curriculum evaluation, which was approved in 2017.

The questionnaire had two parts. The first part comprised nine items covering students’ opinions about the online course and attitudes toward digital learning in general. Respondents rated their degree of agreement with the item statements (“true”; mostly true”; “neutral”; “mostly untrue”; “not true”). The second part was used to characterize students’ acceptance of three different digital teaching formats (lectures, videos featuring real patient scenarios, and online practical skills education). Rating options ranged on a five-item from (1) excellent, (2) good, (3) sufficient, (4) moderate, to (5) poor.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to characterize the data. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Teaching format data were analyzed using the Chi-squared and Kruskal–Wallis tests. The analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 19; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

One hundred of 103 students who took the digital course submitted questionnaires after course completion (97% response rate). After the exclusion of two incomplete questionnaires, data from 98 (98%) questionnaires were included in the analysis. Forty (41%) of the respondents were male and 58 (59%) were female. The median age was 25 years (range, 23–50 years, Table 1).

Students’ opinions about the online course content and structure

Most [n = 87 (89%)] students agreed that the online course topics were relevant for praxis [“true”, n = 58 (59%); “mostly true”, n = 29 (30%)]. Three (3%) students found the chosen topics not to be relevant [“mostly untrue”, n = 1 (1%); “not true”, n = 2 (2%)]. Seventy-four (76%) students agreed that the instruction of the online course was well prepared [“true”, n = 40 (41%); “mostly true”, n = 34 (35%)], whereas six (6%) students did not [“mostly untrue” and “not true”, n = 3 (3%) each]. A majority [n = 84 (86%)] of students could follow the online course [“true”, n = 53 (54%); “mostly true”, n = 31 (32%)]; four (4%) students indicated that they had difficulty following it [“mostly untrue”, n = 1 (1%); “not true”, n = 3 (3%)]. Eighty-four (86%) students agreed that the online course improved their knowledge of gynecology and obstetrics [“true”, n = 53 (54%); “mostly true”, n = 31 (32%)]. Eleven (11%) students had a neutral position on this statement, and three (3%) students disagreed with it (Table 2).

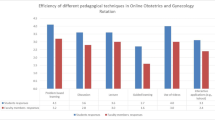

Acceptance of the three digital teaching formats

Overall, ratings for all three teaching formats were good or excellent. Forty-four (45%) rated the online lectures as excellent and 38 (39%) rated them as good [total, n = 82 (84%)]. Similar results were obtained for the video tutorials [n = 86 (88%); excellent, n = 47 (48%); good, n = 39 (40%); < good, n = 12 (12%)] and online education in practical skills [n = 87 (89%); excellent, n = 51 (52%); good, n = 36 (37%); < good, n = 11 (11%)] (Table 3). The median rating was highest for the online lectures [1.7 (range, 1–4)], followed by the video tutorials [1.7 (range, 1–5)] and online education in practical skills [1.6 (range, 1–6)], but the ratings did not differ significantly among formats (p = 0.368).

Students’ opinions about online learning

Most [n = 74 (76%)] students indicated that an online course cannot replace a practical course with patient contact in the hospital. Eleven (13%) students had neutral responses to this item and 13 (13%) students agreed that an online course can replace a practical course [“true”, n = 4 (4%); “mostly true”, n = 9 (9%)]. 47 students (46%) indicated that they did not prefer online to traditional lectures [“mostly untrue”, n = 27 (28%); “not true”, n = 19 (19%)]; 38% (n = 37) of students preferred online lectures [“true”, n = 19 (19%); “mostly true”, n = 18 (18%)] and 15% (n = 16) had neutral opinions on this statement. Seventy (71%) students indicated that they would welcome the integration of more online teaching in the future [“true”, n = 45 (46%); “mostly true”, n = 25 (26%)] (Table 2).

Students’ opinions about learning without real patients

Most [n = 72 (74%)] students missed learning with real patients [“true”, n = 45 (46%); “mostly true”, n = 27 (28%)]; 13 (13%) students had a neutral opinion on this statement and 13 (13%) students did not agree with it [“mostly untrue”, n = 10 (10%); “not true”, n = 3 (3%)]. The majority [n = 89 (91%)] of students indicated that they desired further learning with real patients [“true”, n = 72 (74%); “mostly true”, n = 17 (17%)] (Table 2).

Discussion

This survey of medical students who took an online course in gynecology and obstetrics that replaced a face-to-face practical course emphasizes that for medical students online teaching can be a good option for learning during COVID 19 pandemic, but cannot replace conventional teaching in the university hospitals. Most participants indicated that they desire more integration of online teaching in the future. In addition, all three digital teaching formats used in the course (online lectures, video tutorials featuring real patient scenarios and online education in practical skills) received good ratings.

As modern technology and web-based systems are now integral parts of everyday life, medical students’ demand for and use of digital learning options (e.g., self-directed programs from local universities and other institutions) has increased [9]. These students’ use of social media platforms has also increased and provides the opportunity to interact, discuss cases, and study in session for examinations [10]. The COVID-19 pandemic obligated students to engage in digital learning and revitalized digital learning options [11]. For example, during the period of campus closure, universities in China implemented 24,000 online courses (401 including virtual experimental simulation and 22 providing learning platforms), coordinated by the Chinese Ministry of Education, which monitored online education progress and quality [12]. A survey of 39,854 students at the Southeast University in China emphasized the importance of this tremendous undertaking; 50% of respondents believed that the planned teaching objectives were attained fully [12]. The survey also revealed that students prefer a mixture of different learning formats, such as the use of recorded videos in combination with live courses; this mixed teaching style appeared to increase students’ participation and mitigate the impact of unstable networks [12]. The researchers concluded that in the absence of face-to-face communication, teachers need to put greater effort into preparing for online courses, innovating and designing lessons [12]. The good ratings that students gave to the different teaching formats in this study are in line with these findings, but our students also indicated that teaching and learning with real patients is elementary for future curricula.

Data from the University of Washington document a tenfold increase in digital education in pathological anatomy for distant students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such a course similar to ours was a comprehensive 2-week remote-learning program for third- and fourth-year students that included lectures, slide presentations, virtual discussion groups, and case-based activities [13]. A survey on course effectiveness yielded positive student feedback; in contrast to our findings, the students found the educational quality to be equivalent to that of an in-person course [13]. This difference might be explained by the differences in course objectives and teaching subjects, which included a practical skill development in our course in comparison to a theoretical subject like pathological anatomy in the other.

Schulz-Quach et al. examined 670 medical students’ acceptance of a digital course in palliative care that included online lectures, YouTube videos, self-reflection exercises, and interactive case management, and culminated in a multiple-choice examination. In line with our results, responses to a standardized university questionnaire on students’ palliative care competence revealed broad acceptance of digital learning in e-learning and non-e-learning subgroups [14]. The authors also observed no difference in self-estimated palliative care competence between groups, argued to be attributable to the lack of experience-based learning with real patients. Like our findings, this result emphasizes the need for patient contact in the teaching of skills to medical students.

Investigations in 205 medical students found that video lectures were as effective as live lectures for preparation for a medical examination and could be complementary in medical education. The majority, 48% of students preferred live lectures and 27% preferred video lectures [15]. These results are in line with our findings of lecture rating and some students’ preference of online over traditional lectures.

The affinity toward digital learning is known to vary among students; based on a two-semester-long prospective study, Backhaus et al. identified a digital native and traditional learner type. Digital learners had greater difficulty with traditional lectures than with e-learning, whereas traditional learners showed no difference in knowledge gain between formats. The author emphasized that medical educators should be aware of changes in learning habits, and our results may provide hints of such changes [16].

The implementation of video tutorials can be part of skills training like ultrasound teaching, improving participants knowledge and hands-on skills [17]. In a randomized study, Gonzalves et al. investigated the use of video tutorials and slide shows to teach maneuvers for shoulder dystocia to medical and midwifery students. At the end of the course students were evaluated by graders. Scores in practice and theory were significantly higher among students in the video tutorial group, leading the authors to conclude that video tutorials improved learning relative to standard lectures alone [18]. Our survey also showed broad acceptance of video tutorials among medical students.

Schlupeck et al. reported medical students’ acceptance of an online course on wound care; 69% of students found the online course to be superior to a conventional lecture, and students’ perceived competence increased significantly. In line with these results, our students rated the online course highly [19].

Despite the good performance of the digital teaching formats and the broad acceptance of digital learning, our results reflect an important limitation of digital education, namely that it does not allow for learning with real patients. Our students indicated that the online course could not replace a practical course with patient contact and indicated that they missed patient-centered learning, an elementary educational component that enhances students’ understanding and awareness of the complexity of patient care [20, 21]. In addition to bedside-teaching, practical units on diverse topics (e.g., intrauterine devices, conization, laparoscopy, and obstetric ultrasound) with patient contact or realistic scenarios improve medical students’ knowledge and understanding [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

A review of e-based learning programs for nursing students yielded that e-learning is a flexible teaching method, but is not superior to face-to-face patient simulation. The authors concluded that combined traditional and e-based learning could achieve the best results [31].

The limitations of this study include those inherent to survey-based research. Our survey reflects only one semester during COVID 19 pandemic and was performed as single center. Experiences from other universities would be interesting to compare for further approach. In addition, we evaluated only students’ opinions, and not the effectiveness of online teaching, as reflected for example in examination scores. Thus, although the students showed broad acceptance of online teaching, we cannot comment on the effectiveness of this educational approach in terms of knowledge and medical skill acquisition. As the degree of knowledge transfer is a key indicator in the evaluation of teaching methods, additional studies of the relative effectiveness of online and conventional teaching formats are needed.

Conclusion

In this study, we found a high degree of acceptance of digital teaching formats among medical students during COVID 19 pandemic. In particular, the teaching of knowledge via lectures seems to be partially transferable to an online format. To learn practical skills and patient treatment, medical students require patient-centered education. These findings can be used to further implement digital online formats into students’ medical education.

Availability of data and material

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Sahu P (2020) Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Schluchter H, Nauman AT, Ludwig S et al (2020) Quantitative and qualitative analysis on sex and gender in preparatory material for national medical examination in Germany and the United States. J Med Educ Curric Dev 7:238212051989425. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519894253

Müller A, Schmidt F, Pfeiffer N et al (2021) Evaluation eines nutzerorientierten eLearning-Angebots für die Augenheilkunde. Ophthalmologe. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-020-01306-z

O’Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J et al (2018) Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education—an integrative review. BMC Med Educ 18:130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0

Alqudah NM, Jammal HM, Saleh O et al (2020) Perception and experience of academic Jordanian ophthalmologists with E-Learning for undergraduate course during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Med Surg 59:44–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.09.014

Singh A, Min AKK (2017) Digital lectures for learning gross anatomy: a study of their efficacy. Korean J Med Educ 29:27–32. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2017.50

Sandhu P, de Wolf M (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on the undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ Online 25:1764740. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2020.1764740

Scott K, Morris A, Marais B (2018) Medical student use of digital learning resources. Clin Teach 15:29–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12630

Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR (2014) The use of Facebook in medical education—a literature review. GMS Zeitschr Med Ausb 31(3):Doc33. ISSN 1860-3572. https://doi.org/10.3205/ZMA000925

Tabatabai S (2020) COVID-19 impact and virtual medical education. J Adv Med Educ Profession 8. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2020.86070.1213

Sun L, Tang Y, Zuo W (2020) Coronavirus pushes education online. Nat Mater 19:687–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0678-8

Parker EU, Chang O, Koch L (2020) Remote anatomic pathology medical student education in Washington State. Am J Clin Pathol aqaa154. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa154

Schulz-Quach C, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Fetz K (2018) Can elearning be used to teach palliative care?—medical students’ acceptance, knowledge, and self-estimation of competence in palliative care after elearning. BMC Med Educ 18:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1186-2

Brockfeld T, Müller B, de Laffolie J (2018) Video versus live lecture courses: a comparative evaluation of lecture types and results. Med Educ Online 23:1555434. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2018.1555434

Backhaus J, Huth K, Entwistle A et al (2019) Digital affinity in medical students influences learning outcome: a cluster analytical design comparing vodcast with traditional lecture. J Surg Educ 76:711–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.12.001

Back SJ, Darge K, Bedoya MA et al (2016) Ultrasound tutorials in under 10 minutes: experience and results. Am J Roentgenol 207:653–660. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.16402

Gonzalves A, Verhaeghe C, Bouet PE et al (2018) Effect of the use of a video tutorial in addition to simulation in learning the maneuvers for shoulder dystocia. J Gynecol Obstetr Hum Reprod 47:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.01.004

Schlupeck M, Stubner B, Erfurt‐Berge C (2020) Development and evaluation of a digital education tool for medical students in wound care. Int Wound J iwj.13498. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13498

Smith SR, Cookson J, Mckendree J, Harden RM (2007) Patient-centred learning—back to the future. Med Teach 29:33–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701213406

Dickinson BL, Lackey W, Sheakley M et al (2018) Involving a real patient in the design and implementation of case-based learning to engage learners. Adv Physiol Educ 42:118–122. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00174.2017

Field C, Benson LS, Stephenson-Famy A, Prager S (2019) Intrauterine device training workshop for preclinical medical students. MedEdPORTAL 15:mep_2374-8265.10841. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10841

Findeklee S, Breitbach G-P, Radosa JC et al (2020) Significant improvement of laparoscopic knotting time in medical students through manual training with potential cost savings in laparoscopy - an observational study. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 21:150–155. https://doi.org/10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2020.2020.0019

Findeklee S, Spüntrup E, Radosa JC et al (2019) Endoscopic surgery: talent or training? Arch Gynecol Obstet 299:1331–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05116-w

Takacs FZ, Gerlinger C, Hamza A et al (2020) A standardized simulation training program to type 1 loop electrosurgical excision of the transformation zone: a prospective observational study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 301:611–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05416-1

Takacs FZ, Radosa JC, Gerlinger C et al (2019) Introduction of a learning model for type 1 loop excision of the transformation zone of the uterine cervix in undergraduate medical students: a prospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 299:817–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-018-5019-7

Takacs FZ, Solomayer E-F, Juhasz-Böss I et al (2020) Conisation course for medical students-experience from a German University Hospital. J Turk German Gynecol Assoc 21:79–83. https://doi.org/10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2019.2019.0126

Hamza A, Solomayer E-F, Takacs Z et al (2016) Introduction of basic obstetrical ultrasound screening in undergraduate medical education. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294:479–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-4002-9

Hamza A, Radosa JC, Solomayer E-F et al (2019) Introduction of a student tutor-based basic obstetrical ultrasound screening in undergraduate medical education. Arch Gynecol Obstet 300:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05161-5

Hamza A, Warczok C, Meyberg-Solomayer G et al (2020) Teaching undergraduate students gynecological and obstetrical examination skills: the patient’s opinion. Arch Gynecol Obstet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05615-1

McDonald EW, Boulton JL, Davis JL (2018) E-learning and nursing assessment skills and knowledge—an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today 66:166–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.011

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Jennifer Piehl for assistance in editing the final draft of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by a research grant by the Saarland University Hospital (no. HOMFOR2016 T201000789).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GL Olmes: manuscript writing and data management. JSM Zimmermann: data analysis and critical revision of manuscript. L Stotz: data acquisition and editing of the manuscript. ZF Takacs: data acquisition and editing of the manuscript. A Hamza: data acquisition and editing of the manuscript. MP Radosa: project development and critical revision of the manuscript. S Findeklee: providing the questionnaire. E-F Solomayer: project development. JC Radosa: project development, manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following conflicts of interests. JC Radosa has received travel grants from Medac GmbH (Wedel, Germany), Gedeon. Richter (Budapest, Hungary), Celgene (Summit, NJ, USA), Daiichi Sankyo (Tokyo, Japan), and Pfizer (New York City, NY, USA) and has been an honorary speaker for Pfizer. L.S. has received travel grants from Medac GmbH (Wedel, Germany) and Celgene (Summit, USA) outside the scope of this work. E.-F.S. is receiving grants from the University of Saarland, Storz, and Erbe; personal fees and other compensation from Roche (Basel, Switzerland), Pfizer (New York City, NY, USA), Celgene (Summit USA), Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), and Astra Zeneca (Cambridge, UK); and other fees from Esai (Tokyo, Japan), Ethicon (Somerville, NJ, USA), Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, NJ, USA), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), Tesaro (Waltham, MA, USA), Teva (Petach Tikwa, Israel), Medac GmbH (Wedel, Germany), MSD (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Vifor (Sankt Gallen, Switzerland), Gedeon Richter (Budapest, Hungary), Takeda (Tokyo, Japan), and AGE (Buchholz, Germany). L Stotz has received travel grants from Medac GmbH and Celgene outside the submitted work in the past. ZF Takacs has been honary speaker for Samsung and Dr. Kade GmbH. GL Olmes, JSM Zimmermann, A Hamza, MP Radosa, S Findeklee do not have conflicts of interests.

Ethics approval

Waiver.

Consent to participate

Waiver.

Consent for publication

Waiver.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olmes, G.L., Zimmermann, J.S.M., Stotz, L. et al. Students’ attitudes toward digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey conducted following an online course in gynecology and obstetrics. Arch Gynecol Obstet 304, 957–963 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-06131-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-06131-6