Abstract

Purpose

Evidence regarding local recurrence rates in the initial cases after implementation of robot-assisted total mesorectal excision is limited. This study aims to describe local recurrence rates in four large Dutch centres during their initial cases.

Methods

Four large Dutch centres started with the implementation of robot-assisted total mesorectal excision in respectively 2011, 2012, 2015, and 2016. Patients who underwent robot-assisted total mesorectal excision with curative intent in an elective setting for rectal carcinoma defined according to the sigmoid take-off were included. Overall survival, disease-free survival, systemic recurrence, and local recurrence were assessed at 3 years postoperatively. Subsequently, outcomes between the initial 10 cases, cases 11–40, and the subsequent cases per surgeon were compared using Cox regression analysis.

Results

In total, 531 patients were included. Median follow-up time was 32 months (IQR: 19–50]. During the initial 10 cases, overall survival was 89.5%, disease-free survival was 73.1%, and local recurrence was 4.9%. During cases 11–40, this was 87.7%, 74.1%, and 6.6% respectively. Multivariable Cox regression did not reveal differences in local recurrence between the different case groups.

Conclusion

Local recurrence rate during the initial phases of implantation of robot-assisted total mesorectal procedures is low. Implementation of the robot-assisted technique can safely be performed, without additional cases of local recurrence during the initial cases, if performed by surgeons experienced in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The primary surgical treatment of rectal carcinoma is total mesorectal excision (TME) [1]. The introduction of total mesorectal excision caused a reduction in local recurrence, although systemic recurrence rate remained stable [1]. Subsequently, the introduction of laparoscopic TME (L-TME) caused an improvement of short-term outcomes such as length of stay, but did not improve oncological outcomes [2,3,4,5,6].

Over the last two decades, a new minimal invasive technique has been introduced: robot-assisted TME (R-TME). This technique has been developed to overcome difficulties of laparoscopic surgery, which is especially seen in bulky, low rectal tumours of patients with a small pelvis and a high BMI [7]. It is suggested that R-TME might lead to lower rates of involved circumferential resection margin (CRM) and of incomplete TME specimen, due to increased visibility and precision during the surgical procedure [8, 9]. Up to now no clear benefits regarding post-operative morbidity have been shown [9,10,11]. However, in patients operated by experienced surgeons, the rate of primary anastomosis is suggested to be higher [12, 13]. Additionally, oncological outcomes are suggested to be equal between L-TME and R-TME [14].

Although oncological outcomes in patients operated by experienced surgeons might be equal, discussion remains regarding oncological results during the learning curve, especially since a previous study showed high local recurrence rates during the learning curve of R-TME [15], and two others showed high local recurrence rates during the learning curve of transanal TME (TaTME) [16, 17]. Although it is suggested that length of the learning curve of R-TME is around 40 cases [18,19,20,21], only few studies discuss oncological outcomes during the learning curve of R-TME, with varying results [19, 22]. Since multicentre data regarding local recurrence of patients operated with R-TME during the learning curve is lacking, this study aims to evaluate the 3-year local recurrence rates in the initial cases of R-TME surgeons in four large Dutch centres. It was hypothesized that the implementation phase of R-TME would be safe regarding oncological outcomes.

Materials and methods

A retrospective multicentre cohort study was performed in four large Dutch hospitals. A protocol, which was not registered, regarding the design, methods, and statistical analysis, was composed prior to the initiation of the study. This study was reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines [23]. The initial R-TME procedures since introduction of the technique in each centre were included, and a split group analysis was done for the initial 10 cases per surgeon (implementation phase), 11–40 cases per surgeon (learning phase), and 41 cases and onwards per surgeon (experienced phase), as the learning curve of R-TME is suggested to be around 40 procedures, and a recent study assessing oncological outcomes during the implementation of TaTME performed the same split group analyses for the initial 10, 11–40, and 41 cases and onwards [16, 18,19,20].

Patients

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they (1) needed total mesorectal excision, (2) were diagnosed with rectal cancer according to the definition as proposed by D’Souza et al. [24], (3) were 18 years or older, and (4) were operated in an elective setting with (5) curative intent and (6) if the performing surgeon had performed > 20 robot cases during the inclusion period. There were no predefined exclusion criteria. Pre-operative work-up, treatment, and follow-up were according to the latest Dutch national guideline for rectal cancer [25]. In short this consisted of colonoscopy with pathological biopsy of the tumour, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the rectum, imaging of the thorax and liver by either X-ray and ultrasound or CT for both. Neoadjuvant therapy in the form of chemoradiation was offered in case of threatened mesorectal fascia (MRF) or cN2 disease. In case of cT3 disease with more than 5 mm extramural invasion or cN1 disease, short-course radiotherapy was offered. Final treatment decisions were made in a multidisciplinary team meeting. Follow-up consisted of 6 monthly CEA and imaging of chest and liver during the first 2 years, and thereafter yearly up to 5 years.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the comparison of (multifocal) local recurrence at 3 years of follow-up between the initial 10 R-TME cases (implementation phase), cases 11–40 (learning phase), and case 41 and onwards (experienced phase) per surgeon. Secondary outcomes include comparison of overall survival, disease-free survival, and systemic recurrence at 3 years follow-up between the implementation phase, learning phase, and experienced phase.

Data capturing

All hospitals provided their local data of the obligatory Dutch Colorectal audit (DCRA), including the unique patient number. After pseudonymization, missing and incomplete data was added to the database by accessing the local hospitals’ electronical medical record (EMR). In addition, local recurrence, systemic recurrence, and survival data were added using the local hospitals’ EMR. Informed consent was deemed unnecessary according to the Dutch Medical Treatment Agreement Act. The regional medical ethical committee and local ethical committees of all hospitals gave approval for the study (MEC-U, AW20.002, W19.096).

Baseline characteristics included age, sex, BMI, ASA classification, distance of the tumour to the anorectal junction (ARJ) on MRI, pre-operative mesorectal fascia involvement, neoadjuvant therapy, type of procedure performed, sequential case performed per centre, clinical and pathological TNM classification, histological tumour type, positive circumferential resection margin rate and quality of the TME according to Quirke [26]. Positive CRM was defined as any tumour tissue at a distance of ≤ 1 mm from the circumferential margin. Additionally, 30-day morbidity, mortality, reintervention rate, readmission rate, and anastomotic leakage rate were registered. Thirty-day morbidity was classified according to Clavien-Dindo [27]. Major morbidity was defined as Clavien-Dindo grade III or higher. Anastomotic leakage within 30 days was registered and classified according to the definition of the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer [28]. Overall survival was defined as being alive at 3 years of follow-up. Disease-free survival was defined as being alive without recurrent disease at 3 years of follow-up. Systemic recurrence was defined as any distant metastasis, either pathologically proven or as a lesion suspect for metastasis on imaging that showed growth on consecutive imaging. Local recurrence was defined as tumour deposit located in the pelvic cavity, with pathological proven adenocarcinoma, or growth on consecutive imaging if histopathological confirmation was absent. Multifocal local recurrence was defined as two or more separate deposits of recurrence in the pelvis. Location of local recurrence was classified according to the classification by Georgiou et al. [29].

Robot-assisted training programme

All four centres started with R-TME after an e-learning, animal surgery, and proctoring of five procedures by an experienced R-TME surgeon as part of the training programme of Intuitive Surgical. The proctored cases were included in the implementation phase (cases 1–10). All surgeons adopting the R-TME technique in the four different centres had extensive experience with L-TME before starting with R-TME, with more than 200 L-TME and more than 100 open TME procedures performed per surgeon. Centres started with the technique between 2011 and 2016. In centre the A cases were operated using the DaVinci Xi, performed by one dedicated surgeon. Centre B and C used the DaVinci Si, and in both centres, two dedicated surgeons and a dedicated team of OR nurses performed the procedures. Centre D used the DaVinci Xi, performed by two dedicated surgeons.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using R (version 3.6.1). Categorical and binary variables were compared using the X2 test. Continuous variables were compared using the independent T-test or the Mann–Whitney test, depending on the distribution. Survival curves were plotted in Kaplan-Meijer graphs. Comparisons were made between the initial 10 cases (implementation phase), cases 11–40 (learning phase), and case 41 and onwards (experienced phase) per surgeon. Finally, a multivariable Cox regression analysis, using backward regression, was performed for local recurrence at 3 years of follow-up to evaluate the independent effect of case load per surgeon. Confounding factors taken into account were sex (male/female), BMI (< 25/25–30/ > 30), distance of the tumour from the ARJ (≤ 3 cm/ > 3 cm), mesorectal fascia involvement on pre-operative MRI (yes/no), neoadjuvant therapy (none/radiotherapy/chemoradiation), pathological T stage (0–2/3–4), pathological N stage (0/1–2), pathological M stage (0/1), pathological CRM (≤ 1 mm, > 1 mm), TME quality (incomplete/complete or nearly complete), and pelvic sepsis (no/yes).

Results

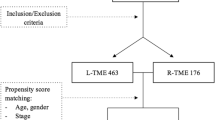

A total of 557 patients were identified in the selected hospitals as receiving an R-TME, after exclusion of 5 patients that were treated with palliative intent, and 21 cases that were treated by surgeons that performed < 20 patients. This resulted in 531 patients, with 70 patients in the implementation phase (cases 1–10 per surgeon), 189 patients in the learning phase (cases 11–40 per surgeon), and 272 patients in the experienced phase (case 41 and onwards) (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Baseline characteristics

Patients had a mean age of 67 years (SD 10.4), with a mean BMI of 26 (SD 4.0). The majority of patients (62.7%) were male, and most were classified as ASA II (62.9%). The median distance of the tumour to the ARJ was 5 cm (IQR 3–8), a cT4 tumour was present in 13.4% of the patients, and the majority of patients received neoadjuvant therapy, either by chemoradiation (36.5%) or radiotherapy alone (34.1%). In the implementation phase a lower percentage of MRF involvement was observed with a higher percentage of missing data. In the same group, a lower percentage of cT2 tumours was observed (Table 1).

Regarding the postoperative outcomes, 33.9% of the patients underwent an APR, 55.8% underwent a LAR with the construction of an anastomosis, and 10.4% underwent a LAR with the construction of an ending colostomy. The TME specimen was incomplete in 3.4% of patients, while a positive CRM was present in 5.8% of the patients (Table 2). Significantly more patients had a metastasis in the group of the implementation phase.

Local recurrence

Local recurrence at 3 years was present in 25 cases (5.5%) in the total group. This was equally distributed between the implementation phase, learning phase, and experienced phase (4.9% versus 6.6% versus 5.0%, p = 0.85). Multifocal local recurrence was seen in 0% versus 37.5% versus 12.5% of the cases of local recurrence for respectively the implementation, learning, and experienced phase (Table 3). Univariable Cox regression analysis showed that mesorectal fascia involvement, pT stage 3–4, pN stage 1–2, positive circumferential resection margin, and incomplete TME margin were associated with local recurrence. In the multivariable analysis, only mesorectal fascia involvement (OR 2.73 [95% CI: 1.21, 6.14]) and pN stage 1–2 (OR 4.27 [95% CI: 1.84, 9.93]) remained. The implementation phase, learning phase, and experienced phase were not associated with difference in local recurrence (Table 5).

Out of the 25 cases of local recurrence, three cases occurred during the implementation phase and 10 cases occurred during the learning phase. Five cases of local recurrence were solely local recurrences without additional systemic recurrences, two cases developed a systemic recurrence after an initial local recurrence, and 9 cases of local recurrence were accompanied with a systemic recurrence. In all but four patients, local recurrence was treated with palliative intent, either due to age and co-morbidities or due to progression of the disease (Tables 4 and 5).

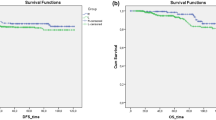

Survival and systemic recurrence

Median follow-up time was 32 months (IQR: 19–50). Overall survival at 3 years of follow-up was 89.1%, disease-free survival was 76.8%, and systemic recurrence was 20.2%. No significant differences between the different phases were found (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to describe oncological outcomes in four Dutch R-TME centres during the period of introduction of the R-TME technique, and shows a local recurrence rate of 4.9% at 3 years of follow-up for the initial 10 cases per surgeon and a local recurrence rate of 6.6% for cases 11–40 per surgeon. Implementation phase, learning phase, or experienced phase was not associated with a higher rate of local recurrence.

Local recurrence was adequate with 4.9%, 6.6%, and 5.0% at 3 years of follow-up. This is in line with results of large randomized controlled trials comparing open with L-TME, showing local recurrence rates of around 5% [3,4,5,6]. In our study, only patients with a rectal tumour according to the new definition by D’Souza et al. [24] were included, and patients with cT4 tumours or mesorectal fascia involvement on pre-operative MRI were not excluded. Compared to the aforementioned large randomized controlled trials, this could have led to the inclusion of more difficult tumours, as cT4 tumours, pre-operative mesorectal fascia involvement, and lower tumours are associated with a higher risk of local recurrence [30]. Furthermore, patients operated during the implementation phase had a significantly higher rate of pM1. Nevertheless, this did not result in worse oncological outcomes.

Other studies reporting on local recurrence rates in R-TME centres during implementation of the technique have described low local recurrence rates as well [31,32,33,34,35]. However, these studies are mostly small studies, subject to significant bias, with short follow-up times in a relatively young and healthy population. In contrast, a Dutch single-centre study regarding the initial 77 cases of R-TME showed a local recurrence rate of 9.5% at 2 years of follow-up [15]. Additionally, the authors reported a positive CRM rate of 10.4%, suggesting inadequate technical dissection, as an effect of the learning curve that had not yet been fulfilled. These results are not in line with the results of our study. Perhaps this could be explained by difference in experience of the surgeon with L-TME, as all surgeons in the present study had profound experience with L-TME. L-TME and R-TME both use a top-down approach; therefore, experience with L-TME might influence outcomes of R-TME during the initial cases. More recently, a study reporting on the implementation of R-TME in a large centre with surgeons having profound experience with L-TME showed a local recurrence rate of 4.0% at 2 years of follow-up with a median follow-up of 28 months [36]. This supports our suggestion that the learning curve of R-TME does not lead to additional local recurrences if performed by surgeons having experience with L-TME.

This is in contrast to the learning curve of TaTME that is suggested to be associated with local recurrence rates of up to 10%, with multifocal recurrence rates of up to 67% during the learning curve [16, 17, 37]. We suggest that this might be due to the fact that TaTME uses a bottom-up approach, in which anatomical landmarks are different compared with the top-down approach of open TME, L-TME, and R-TME. Additionally, the use of a purse string in the TaTME technique is suggested to be an explanation for the difference in (multifocal) local recurrence between the techniques [37]. Although high rates of local recurrence have been observed in these studies, low rates of local recurrence have been shown as well, especially in studies reporting on oncological outcomes after obtaining the learning curve of TaTME [16, 38,39,40]. Perhaps experience with the technique is more important than the technique itself [41]. Finally, reports on additional morbidity are not limited to TaTME only. During the beginning of the adaptation of laparoscopic colorectal surgery, reports demonstrated local recurrence rates of 10.5% and the occurrence of port-site metastasis during the learning curve [42, 43].

Although our results suggest that R-TME performed by experienced L-TME surgeons does not lead to additional local recurrence during the initial cases after introduction of R-TME, certain limitations should be taken into account regarding the results of this study. First, this is a retrospective study, which bares the risk of selection bias. More importantly, this might be even more apparent as patients are especially selected during the beginning of the implementation of a new technique. Mostly patients with ‘easy’ tumours are selected during the initial phase of implementation, while patients with more ‘difficult’ tumours are operated using the new technique after a certain degree of experience has been established. Although a lower rate of mesorectal fascia involvement and cT2 rate was observed in the group containing the initial 10 cases per surgeon, it is unlikely that this affected outcomes, as pathological T stage and positive CRM were comparable. Furthermore, we did not exclude patients with cT4 tumours or stage IV disease and we only included patients with a rectal tumour according to the new definition by D’Souza et al. [24]. This could potentially have led to relatively more low rectal tumours, and therefore more APRs, as recto-sigmoidal tumours have been excluded due to this definition. Nevertheless, baseline characteristics of our cohort do not reveal such selection bias after comparison with national data [44]. Secondly, although this study aims to include patients operated during the learning curve, a clear definition of the learning curve is as of yet lacking. Since earlier reports on the learning curve in R-TME suggest length of the learning curve to be between 20 and 75 patients, and a recent study aimed at assessing oncological outcomes during the implementation of TaTME included the first 40 patients who underwent TaTME, we used the latter inclusion criteria for comparability. Thirdly, this study reports on oncological outcomes during the introduction of the technique of only four centres. Preferably more centres would have been included, resulting in greater external validity. In addition, the contributing centres differed regarding the starting year of the technique, number of annually operated patients and patients included, which might have affected outcomes. However, despite these differences, local recurrence remained within clinically safe margins. Fourth, this is a non-comparative study. Therefore, additional prospective studies comparing the learning curve of the minimal invasive techniques should be performed. Finally, we did not perform a risk-adjusted cumulative sum analysis (RA-CUSUM). Although this might be the preferred method for evaluating the learning curve, this method is not favourable for outcomes with a low incidence such as local recurrence.

Concluding, the use of R-TME during the implementation of the technique, performed by experienced L-TME surgeons, is safe with regard to oncological outcomes, and more specifically local recurrence. R-TME might be a safe alternative besides L-TME and TaTME, as it does not lead to additional local recurrence during the initial cases. Nevertheless, comparative prospective studies are necessary to directly compare results of L-TME, R-TME, and TaTME during the learning curve.

References

Heald RJ, Ryall RDH (1986) Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet 327:1479–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91510-2

Vennix S, Pelzers L, Bouvy N et al (2014) Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Fleshman J, Branda ME, Sargent DJ et al (2019) Disease-free survival and local recurrence for laparoscopic resection compared with open resection of stage II to III rectal cancer: follow-up results of the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 269:589–595. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003002

Stevenson ARL, Solomon MJ, Brown CSB et al (2019) Disease-free survival and local recurrence after laparoscopic-assisted resection or open resection for rectal cancer: the Australasian Laparoscopic Cancer of the Rectum Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg 269:596–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003021

Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH et al (2014) Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 15:767–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70205-0

Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA et al (2015) A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 372:1324–1332. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1414882

Clancy C, O’Leary DP, Burke JP et al (2015) A meta-analysis to determine the oncological implications of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Color Dis 17:482–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12875

Sammour T, Malakorn S, Bednarski BK et al (2018) Oncological outcomes after robotic proctectomy for rectal cancer: analysis of a prospective database. Ann Surg 267:521–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002112

Jayne D, Pigazzi A, Marshall H et al (2017) Effect of robotic-assisted vs conventional laparoscopic surgery on risk of conversion to open laparotomy among patients undergoing resection for rectal cancer. JAMA 318:1569. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7219

Grass JK, Perez DR, Izbicki JR, Reeh M (2018) Systematic review analysis of robotic and transanal approaches in TME surgery- a systematic review of the current literature in regard to challenges in rectal cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 45:498–509

Bhangu A, Minaya-Bravo AM, Gallo G et al (2018) An international multicentre prospective audit of elective rectal cancer surgery; operative approach versus outcome, including transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME). Color Dis 20:33–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14376

Burghgraef TA, Crolla RMPH, Verheijen PM et al (2021) Robot-assisted total mesorectal excision versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision: a retrospective propensity score matched cohort analysis in experienced centers. Dis Colon Rectum

Hol JC, Burghgraef TA, Rutgers MLW et al (2021) Comparison of laparoscopic versus robot-assisted versus transanal total mesorectal excision surgery for rectal cancer: a retrospective propensity score-matched cohort study of short-term outcomes. Br J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab233

Burghgraef TA, Hol JC, Rutgers ML et al (2022) Laparoscopic versus robot-assisted versus transanal low anterior resection: 3-year oncologic results for a population-based cohort in experienced centers. Ann Surg Oncol 29:1910–1920. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10805-5

Polat F, Willems LH, Dogan K, Rosman C (2019) The oncological and surgical safety of robot-assisted surgery in colorectal cancer: outcomes of a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc 33:3644–3655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-06653-2

Van Oostendorp S, Belgers H, Hol J et al (2021) Learning curve of TaTME for rectal cancer is associated with local recurrence; results from a multicentre external audit. Color Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15722

Wasmuth HH, Færden AE, Myklebust T et al (2020) Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer has been suspended in Norway. Br J Surg 107:121–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11459

Kim HJ, Choi G-SS, Park JS, Park SY (2014) Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for robotic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: lessons from a single surgeon’s experience. Dis Colon Rectum 57:1066–1074. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000174

Park EJ, Kim CW, Cho MS et al (2014) Multidimensional analyses of the learning curve of robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: 3-phase learning process comparison. Surg Endosc 28:2821–2831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3569-8

Jiménez-Rodríguez RM, Díaz-Pavón JM, de la Portilla de Juan F, et al (2013) Learning curve for robotic-assisted laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 28:815–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-012-1620-6

Olthof PB, Giesen LJX, Vijfvinkel TS et al (2020) Transition from laparoscopic to robotic rectal resection: outcomes and learning curve of the initial 100 cases. Surg Endosc 1:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07731-0

Noh GT, Han M, Hur H et al (2020) Impact of laparoscopic surgical experience on the learning curve of robotic rectal cancer surgery. Surg Endosc 1:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-08059-5

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61:344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

DʼSouza N, de Neree Tot Babberich MPM, d’Hoore A, et al (2019) Definition of the rectum: an international, expert-based Delphi consensus. Ann Surg XX:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003251

Landelijke werkgroep Gastro Intestinale Tumoren (2019) Richtlijn colorectaal carcinoom 4.0. https://www.oncoline.nl/colorectaalcarcinoom. Accessed 13 Jan 2020

Nagtegaal ID, Van de Velde CJH, Van Der Worp E et al (2002) Macroscopic evaluation of rectal cancer resection specimen: clinical significance of the pathologist in quality control. J Clin Oncol 20:1729–1734. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.07.010

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [pii]

Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W et al (2010) Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum : a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.012

Georgiou PA, Tekkis PP, Constantinides VA et al (2013) Diagnostic accuracy and value of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in planning exenterative pelvic surgery for advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 49:72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.025

Kusters M, Marijnen CAM, van de Velde CJH et al (2010) Patterns of local recurrence in rectal cancer; a study of the Dutch TME trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 36:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2009.11.011

Pigazzi A, Luca F, Patriti A et al (2010) Multicentric study on robotic tumor-specific mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 17:1614–1620. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-0909-3

Lim DR, Bae SU, Hur H et al (2017) Long-term oncological outcomes of robotic versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision of mid–low rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy. Surg Endosc 31:1728–1737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5165-6

Ghezzi TL, Luca F, Valvo M et al (2014) Robotic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: comparative study of short and long-term outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol 40:1072–1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2014.02.235

Baek JH, McKenzie S, Garcia-Aguilar J, Pigazzi A (2010) Oncologic outcomes of robotic-assisted total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer. Ann Surg 251:882–886. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c79114

Park EJ, Cho MS, Baek SJ et al (2015) Long-term oncologic outcomes of robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 261:129–137. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000613

Hol JC, Dogan K, Blanken-Peeters CFJM et al (2021) Implementation of robot-assisted total mesorectal excision by multiple surgeons in a large teaching hospital: morbidity, long-term oncological and functional outcome. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.2227

van Oostendorp SE, Belgers HJ, Bootsma BT et al (2020) Locoregional recurrences after transanal total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer during implementation. Br J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11525

Hol JC, van Oostendorp SE, Tuynman JB, Sietses C (2019) Long-term oncological results after transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol 23:903–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-02094-8

Roodbeen SX, Spinelli A, Bemelman WA et al (2020) Local recurrence after transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Publish Ah: https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003757

Caycedo-Marulanda A, Lee L, Chadi SA et al (2021) Association of transanal total mesorectal excision with local recurrence of rectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2036330. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36330

Rockall TA (2021) Transanal total mesorectal excision: the race to the bottom. Br J Surg 108:3–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znaa053

Wexner SD, Cohen SM (1995) Port site metastases after laparoscopic colorectal surgery for cure of malignancy. Br J Surg 82:295–298

Kim CH, Kim HJ, Huh JW et al (2014) Learning curve of laparoscopic low anterior resection in terms of local recurrence. J Surg Oncol 110:989–996. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23757

Detering R, tot Babberich MPDN, Bos CRK et al (2020) Nationwide analysis of hospital variation in preoperative radiotherapy use for rectal cancer following guideline revision. Eur J Surg Oncol 46:486–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2019.12.016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the study: Burghgraef, Crolla, Smits, Consten, Verheijen, Fahim, van der Schelling, Stassen, Melenhorst, Verheijen. Acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data of the study: Fahim, Burghgraef, Crolla, Smits, Verheijen, Consten. Drafting the manuscript: Burghgraef. Revising the manuscript critically: Burghgraef, Crolla, Smits, Consten, Verheijen, Fahim, van der Schelling, Stassen, Melenhorst, Verheijen. Final approval of the manuscript: Burghgraef, Crolla, Smits, Consten, Verheijen, Fahim, van der Schelling, Stassen, Melenhorst, Verheijen.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Crolla, Verheijen, and Consten receive fees from Intuitive Surgical. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The regional and local medical ethical committees gave approval.

Consent to participate

Waived by the regional medical ethical committee.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burghgraef, T.A., Crolla, R.M.P.H., Fahim, M. et al. Local recurrence of robot-assisted total mesorectal excision: a multicentre cohort study evaluating the initial cases. Int J Colorectal Dis 37, 1635–1645 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-022-04199-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-022-04199-3