Abstract

Purpose

Anal cancer is a mainly treated with chemoradiotherapy. A small number of patients undergo salvage surgery. There are few published studies investigating quality of life and functional outcome after treatment for anal cancer. The aim of this review was to explore the literature and identify areas for further research.

Methods

A search was conducted in Medline using MESH terms related to anal cancer and quality of life. Two investigators selected and reviewed articles based on titles and abstracts. Three investigators read and reviewed the included articles and collected relevant data. The included articles were evaluated using the minimum standard checklist, and key findings were summarised in a chart.

Results

Some 15 articles, and a total of 802 patients, were deemed eligible. The results differed slightly among the studies. The incidence of symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, insomnia and appetite loss was higher than among healthy volunteers. Bowel function, urinary function and sexual function were negatively affected. Some studies found that, compared with the normal population, anal cancer survivors scored clinically significant worse in the functional scales in QLQ-C30.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is apparent that several functional problems affect the quality of life of patients with anal cancer. There are few studies which have investigated quality of life after treatment for anal cancer. Interventions to address issues related to anal cancer treatment may improve long-term quality of life in this patient group.

Trial registration

CRD42017059787

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anal cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) is a rare disease with an annual incidence between 1 and 2 per 100,000 inhabitants accounting for 1–1.5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. In Sweden, 150–200 new cases are registered each year with increasing incidence [1]. Like cervical cancer, anal cancer is strongly associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is the leading cause of approximately 80–85% of the tumours [2, 3].

Radio and chemotherapy (RCT) has been the cornerstone treatment of anal cancer since the 1970s, when studies by Nigro et al. showed that the survival rate for patients treated with RCT was as good or higher than for patients who underwent surgery alone [4,5,6]. Today, a majority of patients with anal carcinoma are treated with fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C (MMC) in combination with radiotherapy, in doses normally up to 45–60 Gy, depending on TNM-stage. A small group of patients undergo salvage surgery with a permanent colostomy due to lack of treatment response or tumour recurrence. A large Nordic study recently showed that inclusion in a treatment protocol has a positive effect on outcome [7].

Studies investigating QoL after treatment for anal cancer are rare. A review article by Sodergren et al. summarised the few published studies up to 2014 and found that the most common complications after treatment for anal cancer were skin conditions, faecal incontinence and sexual problems, but psychological side effects such as depression and fatigue also occurred [8]. However, since then, some longitudinal studies with baseline data have been published [9,10,11,12].

Quality of life in other types of malignancy in the gastrointestinal canal than anal cancer has been widely investigated using standardised questionnaires such as focusing on anorectal, bladder and sexual function after treatment. These questionnaires were designed for patients treated for rectal cancer and other malignancies in the gastrointestinal canal. Recently, however, Sodergren et al. published an EORTC questionnaire for anal cancer, EORTC QLQ-ANL27, which has not yet been used in any other study [13] as far as we know. The aim of this review article is to investigate the existing research on quality of life and evaluate the need for further research in the subject.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

The trial is registered in the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews, registration number: CRD42017059787.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies were published prior to December 2016. Endpoints were quality of life after treatment of anal cancer. Case reports, editorials, review articles and comments were excluded.

Information sources/search strategy

The PICO that was set up was patients with anal cancer, treatment with chemoradiotherapy and or surgery, no control was used, the outcome was functional outcome and quality of life. A search using the PICO was conducted in Medline, for English language articles only. A combination of MESH terms and other terms related to anal cancer, treatment, and quality of life were used (see Table 1). Articles of interest, found through references in the published articles, were also assessed for eligibility.

Study selection

Two investigators independently reviewed and selected articles by reading the titles and abstracts. Articles concerning other diseases than carcinoma of the anal canal, and studies lacking quality of life as an endpoint after treatment of anal carcinoma, were excluded. We included randomised controlled trials, case-report trials and prospective trials. Disagreement between the two independent investigators was solved by discussion.

Data collection process

Three reviewers read the full articles that were selected for a closer investigation. Relevant data were retrieved and collected in a data form as Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Data items

Data about main author, year of publication, type of trial, number of patients, method of evaluating quality of life, and main findings were abstracted by two authors and collected in a data form.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two investigators assessed risk of bias by studying the included articles using the minimum standard checklist developed by Efficace et al. [14].

Summary measures

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the minimum standard checklist for studies assessing QoL, developed by Efficace et al. [14].

Synthesis of results

The key findings and study characteristics from all included studies were summarised in a chart.

The results regarding general quality of life, symptom scales and long-term results from the studies that used the EORTC QLQ-C30 for evaluating quality of life were summarised in a table and compared with a cohort of healthy volunteers.

Risk of bias across studies

Risk of bias was assessed by one author and summarised in the results.

Result

Study selection and literature search

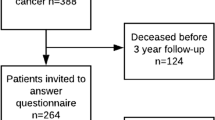

After screening 736 potential studies using title and abstract, 15 articles were found eligible and in total, 802 patients were included in the review (see Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 15 included observational studies are listed in Table 1. Twelve studies were cross sectional out of which ten were single-centres with inclusion periods varying from 8 to 24 years. Two Scandinavian multi-centre cross-sectional studies retrieved patients using national registers recruiting relatively large cohorts. Three studies were longitudinal assessing quality of life before and after treatment of anal cancer; in one of these, the authors compared two different techniques of radiation [15]. The earliest inclusion period started in the 1970s, but the majority of patients received treatment during the 1990s up to the 2010s.

The quality of the QoL items reported was generally high with a mean of 8.3 for the 15 studies, well above the recommended level of 8 (Table 2) [14].

The time interval from treatment to assessment of QoL differed between the studies. In order to ensure long-term QoL evaluation, five studies required a minimum follow-up period of 2 years. Two of the longitudinal studies measured QoL in time intervals up to several years after treatment, while the third longitudinal study assessed QoL at two occasions only, before and directly after treatment.

The number of patients enrolled varied from 14 to 128. The two largest studies, including 128 and 84 patients, respectively, were based upon national registries [10, 16]. Median age varied from 51 to 69 years and the response rate of QoL assessment was between 40 and 89%.

Drop-out analysis

A drop-out analysis was performed in 8 of the 14 studies. Knowles and Bentzen reported that patients who declined participation were older with more comorbidities, but no differences in tumour characteristics were seen [11, 16]. Tournier-Rangeard found that patients, who answered the follow-up QoL questionnaire, had higher QoL in the baseline questionnaire [17]. Drop-out analyses in the remaining studies showed no difference in characteristics between responders and non-responders concerning tumour characteristics, age or comorbidities.

QoL instruments

In the absence of a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire designed for anal cancer survivors, most authors have used previously validated QLQ-CR38/QLQ-CR29 or FACT-C designed for colorectal cancer [18]. These questionnaires collect information regarding anxiety, body image, sexual function, urinary function and anorectal function.

QLQ-C30, a generic cancer instrument, has previously been validated numerous times for different cancer cohorts [19, 20] in different countries and cultures [21,22,23,24], as well as for patients with curable and palliative disease. QLQ-C30 contains 30 items, 5 multi-item functional scale (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning), 6 single-item symptom scale (including fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation diarrhoea and financial difficulties) and a multi-item named global health score measuring the overall physical condition and general QoL. A low global health score indicates poor physical condition and/or low overall quality of life [25]. In nine of the included studies, QoL was assessed using QLQ-C30 with the addition of QLQ-CR29 or QLQ-CR38 [26].

When analysing and comparing results from QLQ-C30, the authors have used the recommendations of Osoba et al. [27] grading a change of less than 5 to be small, 5–10 to be moderately relevant and any change above 10 points to be clinically significant.

Two authors chose to evaluate QoL using the validated FACT-C, a part of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) [28, 29] measurement system. This questionnaire contains self-reporting instruments for evaluating QoL in patients with cancer and other chronic illnesses [30]. FACT-C combines FACT-G, assessing general QoL with the 9-item colorectal cancer subscale (CCS). Two of these items address issues concerning stoma. FACT-C contains four items: physical, social, emotional and functional wellbeing [31, 32]. In all, FACT-C contains 36 items presented on a 5-point Likert scale.

Two studies used a questionnaire developed by Eypasch for gastrointestinal disease, not limited to cancer [33]. Sunesen and co-workers constructed their own anal cancer–specific questionnaire [10]. This questionnaire is based on existing validated questionnaires and an expert panel including three colorectal surgeons and one radiation oncologist.

Synthesis of studies

General quality of life

Results from the QLQ-C30 questionnaire from six cross-sectional studies [11, 16, 34,35,36,37] are listed in Table 3, together with reference data from a Swedish [38] and a German [39] healthy cohort. The numerical value of global health status, after treatment of anal carcinoma, varies from 60 to 72.

Data of QLQ-C30 score from the three longitudinal studies [9, 12, 17] are displayed in Table 4. After an initial decrease immediately after treatment, global health status increased to baseline levels [12] or well beyond a few months after treatment [9, 17].

In several studies [34, 36, 40, 41], sphincter function was found to independently affect overall QoL. Fakhiran as well as Vordermark found that stool incontinence as well as urgency (only Fakhiran) lowered QoL [ref. 42]. Dyspareunia also negatively affected QoL (ref. Fakhiran) as did higher age [43].

Functioning scales in QLQ-C30

Bentzen et al. [16] and Welzel et al. [34] found that anal cancer survivors scored clinically significantly worse for all five functional scales in QLQ-C30 compared with the normal population. The largest difference (> 20p) was seen for role and social functioning. Provencher [37] also found a clinically significant difference for social function and Jephcott [35] demonstrated a difference for all functions, but clinically non-significant for emotional and cognitive functioning.

As with global health score, however, functional scales were back to baseline values within a year, except from role function and social function, which had improved clinically significantly compared with baseline data.

Symptom scales, long-term results

General cancer–specific symptoms addressed in QLQ-C30 are listed for the applicable studies in Tables 3 and 4. Compared with volunteers, Bentzen et al. [16] found that anal cancer survivors scored worse for all symptoms and single items in QLQ-C30 and CR29. Similar findings were made by Welzel et al. who compared their cohort with the German background population. In their study T3/4, low tumour localisation, a long follow-up time, surgery, male gender and being physically inactive had a significantly negative impact on role function and fatigue [34].

One year after treatment, as assessed by Joseph et al. [9], fatigue, pain, appetite loss and constipation were clinically significantly improved compared with baseline data, as was financial difficulties.

Bowel function

In the anal cancer–specific questionnaire created by Sunesen [10], symptoms were identified according to the extent of distress they caused, graded as none, little, moderate or great. Faecal incontinence, faecal urgency and frequency of bowel movements were common and caused great distress. Knowles et al. [11] found that 29% of patients altered their daily activity because of bowel dysfunction. As seen in Table 4, diarrhoea increased after treatment and remained increased for the study period in the longitudinal studies. Anal cancer survivors had more diarrhoea than healthy volunteers (Table 3).

Urinary symptoms

Increased urinary frequency was common among anal cancer survivors [9, 37, 42], as was urinary incontinence that increased 10% after treatment [9]. In Sunesen’s study [10], urinary incontinence caused great distress for the majority of the 45% of patients who experienced it.

Symptoms affecting sex life

It was common with a low response rate for questions regarding sex. Women neglected to answer these questions to a larger extent than men, as did anal cancer survivors compared with volunteers. In Sunesen’s study, half of the patients did not answer questions evaluating sexual function and the majority of those stated complete absence of sexual desire and activity as a reason. In Jephcott et al., only 54% of anal cancer survivors answered compared with 80% of healthy volunteers [35] and similar response frequencies have also been reported by Knowles, Welzel and Allal [11, 34, 36].

Compared with healthy volunteers, anal cancer survivors scored worse for sexual problems and men scored worse than women (see Table 5). In Joseph et al., sexual function was significantly decreased for both women and men during treatment, but returned to baseline values after treatment [9].

Bentzen found a clinically significant difference in sexual interest between anal cancer survivors and volunteers for both genders, supported by Provencher and Sunesen [10, 16, 37]. The latter also found that women not interested in sexual activity rated their sexual desire to be “severely decreased” or “non-existing”.

Erectile dysfunction in men and dyspareunia in women was found to be common after anal cancer treatment. Bentzen, Sunesen and Fakhrian all report an incidence of erectile dysfunction between 60 and 71% [10, 16, 40]. Among healthy volunteers, this was 20% [16]. Up to 60% of the female patients experienced some degree of dyspareunia [10, 40] and Joseph et al. found dyspareunia to be the only symptom that did not return to baseline 1 year after treatment [9]. Bentzen et al. found that the biggest difference in QoL was found among female patients experiencing grade 3 dyspareunia compared with those free of dyspareunia, which indicates that dyspareunia is a symptom of great importance [16]. This is corroborated by Sunesen et al. [10].

Discussion

Patients treated for anal cancer have a long-term reduced quality of life compared with healthy individuals, which is accompanied by and in some part due to bowel, urinary and sexual dysfunction. Compared with pre-treatment QoL, the deterioration in QoL seen immediately after treatment improved substantially within the first year.

The decrease in global QoL seen in anal cancer survivors compared with Swedish reference material [38] and healthy volunteers [16, 35] seems to be multifactorial. Consistently throughout the studies, bowel dysfunctions such as faecal incontinence, faecal frequency and faecal urgency seem to have a large impact on quality of life [10, 11, 36, 40]. In the case of bowel dysfunction, a stoma might alleviate some of these symptoms. In one of the included studies, it was shown that patients who underwent an abdominoperineal resection, APR, experienced an increase in general health score and decrease of rectal pain after surgery. Colostomy-free survival is often used as a measure of clinical success. However, for some patients, a stoma might be a relief. In fact, in patients with rectal cancer, it is not certain that a stoma will reduce quality of life [44]. We suggest that perhaps more patients treated for anal cancer would benefit from meeting with a surgeon to evaluate the possible benefit of having a stoma.

Urinary incontinence was identified in several studies as a factor influencing quality of life. The frequency of urinary incontinence was lower than among patients operated for rectal cancer [45,46,47,48,49,50] but in contrast to patients treated for rectal cancer, it remained for a longer period of time [48].

In order to more precisely describe the aetiology of the symptoms, it is important to also evaluate QoL and body functions before treatment. A pre-treatment questionnaire could then be used to identify patients at risk and provide useful information to assist patients early in the post-treatment period to improve quality of life.

Patients treated for anal cancer have an altered sexual life. It is evident from this review that this issue needs to be addressed. The low response rate, however, makes interpretation difficult. In the future, more research should be focused on this area to improve the quality of data. Male sexual function seems to be similar to patients treated for rectal or prostate cancer [48, 51] and it is important that patients are referred to urologists after treatment to try different treatment options. In women, dyspareunia was reported as causing distress and affecting quality of life. This can sometimes be alleviated with support from gynaecologists, but as with sexual problems in men, the issue must be addressed with the patients after treatment cessation.

Risk of bias

The quality of the included papers was assessed using the minimal checklist and the overall quality is high. However, some particular risk of bias is worth mentioning. Anal cancer is a rare disease and the retrospective studies included have inclusion periods well beyond 10 years. The heterogeneity suggests that patients have received different therapies within and across studies. There is also a difference between the trials regarding length of follow-up time, and time from treatment to first evaluation. The low response rates cause a serious risk of selection bias. Few patients in general and women in particular answered questions regarding sexual life rendering this important research field difficult to assess.

The external validity of the studies is compromised by the use of single-centred studies. Only two national cohorts were used. Reports from single-centres may be misleading on a national or international level since these centres may share a special interest in these issues and treat patients accordingly.

Only one study included a questionnaire specifically intended for patients with anal cancer. It is possible that the questionnaires used are insufficient to fully explore the functional results of anal cancer treatment and its impact on quality of life. A validated questionnaire based on in-depth interviews with patients with anal cancer has recently been published [13] and it will be interesting to evaluate whether this will facilitate proper follow-up and identification of functional problems. It is interesting to note that the base line values in several domains of QLQ C-30 are much lower than in a rectal cancer cohort prior to treatment [48]. It is difficult to interpret this, but it may be that the patients with anal cancer present with much more symptoms than patients with rectal cancer.

In summary, it is apparent that patients with anal cancer have several functional problems affecting general QoL. Interventions to address these issues may in the end improve the long-term quality of life in this patient group.

References

Brewster DH, Bhatti LA (2006) Increasing incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus in Scotland, 1975-2002. Br J Cancer 95(1):87–90

Bjorge T, Engeland A, Luostarinen T, Mork J, Gislefoss RE, Jellum E et al (2002) Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for anal and perianal skin cancer in a prospective study. Br J Cancer 87(1):61–64

Grulich AE, Jin F, Conway EL, Stein AN, Hocking J (2010) Cancers attributable to human papillomavirus infection. Sex Health 7(3):244–252

Buroker TR, Nigro N, Bradley G, Pelok L, Chomchai C, Considine B, Vaitkevicius VK (1977) Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a follow-up report. Dis Colon Rectum 20(8):677–678

Nigro ND (1984) An evaluation of combined therapy for squamous cell cancer of the anal canal. Dis Colon Rectum 27(12):763–766

Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B Jr (1974) Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum 17(3):354–356

Leon O, Guren M, Hagberg O, Glimelius B, Dahl O, Havsteen H, Naucler G, Svensson C, Tveit KM, Jakobsen A, Pfeiffer P, Wanderås E, Ekman T, Lindh B, Balteskard L, Frykholm G, Johnsson A (2014) Anal carcinoma - survival and recurrence in a large cohort of patients treated according to Nordic guidelines. Radiother Oncol 113(3):352–358

Sodergren SC, Vassiliou V, Dennis K, Tomaszewski KA, Gilbert A, Glynne-Jones R et al (2015) Systematic review of the quality of life issues associated with anal cancer and its treatment with radiochemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 23(12):3613–3623

Joseph K, Vos LJ, Warkentin H, Paulson K, Polkosnik LA, Usmani N, Tankel K, Severin D, Nijjar T, Schiller D, Wong C, Ghosh S, Mulder K, Field C (2016) Patient reported quality of life after helical IMRT based concurrent chemoradiation of locally advanced anal cancer. Radiother Oncol 120(2):228–233

Sunesen KG, Norgaard M, Lundby L, Havsteen H, Buntzen S, Thorlacius-Ussing O et al (2015) Long-term anorectal, urinary and sexual dysfunction causing distress after radiotherapy for anal cancer: a Danish multicentre cross-sectional questionnaire study. Color Dis 17:O230–O239

Knowles G, Haigh R, McLean C, Phillips H (2015) Late effects and quality of life after chemo-radiation for the treatment of anal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(5):479–485

Han K, Cummings BJ, Lindsay P, Skliarenko J, Craig T, Le LW et al (2014) Prospective evaluation of acute toxicity and quality of life after IMRT and concurrent chemotherapy for anal canal and perianal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 90(3):587–594

Sodergren SC, Johnson CD, Gilbert A, Tomaszewski KA, Chu W, Chung HT et al (2017) Phase I-III development of the EORTC QLQ-ANL27, a health-related quality of life questionnaire for anal cancer. Radiother Oncol 126(2):222–228

Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, Gotay C, Flechtner H, D’Haese S et al (2003) Beyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures: a checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials--does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making? J Clin Oncol 21(18):3502–3511

Oehler-Janne C, Seifert B, Lutolf UM, Studer G, Glanzmann C, Ciernik IF (2007) Clinical outcome after treatment with a brachytherapy boost versus external beam boost for anal carcinoma. Brachytherapy. 6(3):218–226

Bentzen AG, Balteskard L, Wanderas EH, Frykholm G, Wilsgaard T, Dahl O et al (2013) Impaired health-related quality of life after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer: late effects in a national cohort of 128 survivors. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 52(4):736–744

Tournier-Rangeard L, Mercier M, Peiffert D, Gerard JP, Romestaing P, Lemanski C, Mirabel X, Pommier P, Denis B (2008) Radiochemotherapy of locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: prospective assessment of early impact on the quality of life (randomized trial ACCORD 03). Radiother Oncol 87(3):391–397

Ganesh V, Agarwal A, Popovic M, Cella D, McDonald R, Vuong S, Lam H, Rowbottom L, Chan S, Barakat T, DeAngelis C, Borean M, Chow E, Bottomley A (2016) Comparison of the FACT-C, EORTC QLQ-CR38, and QLQ-CR29 quality of life questionnaires for patients with colorectal cancer: a literature review. Support Care Cancer 24(8):3661–3668

Kaasa S, Bjordal K, Aaronson N, Moum T, Wist E, Hagen S et al (1995) The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30): validity and reliability when analysed with patients treated with palliative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 31A(13–14):2260–2263

Michels FA, Latorre Mdo R, Maciel Mdo S (2013) Validity, reliability and understanding of the EORTC-C30 and EORTC-BR23, quality of life questionnaires specific for breast cancer. Rev Bras Epidemiol 16(2):352–363

Nowak W, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, Brzyski P, Salowka J, Kulis D, Richter P (2011) Adaptation of quality of life module EORTC QLQ-CR29 for Polish patients with rectal cancer: initial assessment of validity and reliability. Pol Przegl Chir 83(9):502–510

Kyriaki M, Eleni T, Efi P, Ourania K, Vassilios S, Lambros V (2001) The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30, version 3.0) in terminally ill cancer patients under palliative care: validity and reliability in a Hellenic sample. Int J Cancer 94(1):135–139

Shuleta-Qehaja S, Sterjev Z, Shuturkova L (2015) Evaluation of reliability and validity of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30, Albanian version) among breast cancer patients from Kosovo. Patient Prefer Adherence 9:459–465

Cankurtaran ES, Ozalp E, Soygur H, Ozer S, Akbiyik DI, Bottomley A (2008) Understanding the reliability and validity of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in Turkish cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care 17(1):98–104

King MT (1996) The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 5(6):555–567

Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK (1999) The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 35(2):238–247

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16(1):139–144

Webster K, Cella D, Yost K (2003) The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:79

Lent L, Hahn E, Eremenco S, Webster K, Cella D (1999) Using cross-cultural input to adapt the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) scales. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 38(6):695–702

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):570–579

Ward WL, Hahn EA, Mo F, Hernandez L, Tulsky DS, Cella D (1999) Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res 8(3):181–195

Yost KJ, Cella D, Chawla A, Holmgren E, Eton DT, Ayanian JZ et al (2005) Minimally important differences were estimated for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) instrument using a combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches. J Clin Epidemiol 58(12):1241–1251

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H (1995) Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 82(2):216–222

Welzel G, Hagele V, Wenz F, Mai SK (2011) Quality of life outcomes in patients with anal cancer after combined radiochemotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 187(3):175–182

Jephcott CR, Paltiel C, Hay J (2004) Quality of life after non-surgical treatment of anal carcinoma: a case control study of long-term survivors. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol (Great Britain)) 16(8):530–535

Allal AS, Sprangers MA, Laurencet F, Reymond MA, Kurtz JM (1999) Assessment of long-term quality of life in patients with anal carcinomas treated by radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 80(10):1588–1594

Provencher S, Oehler C, Lavertu S, Jolicoeur M, Fortin B, Donath D (2010) Quality of life and tumor control after short split-course chemoradiation for anal canal carcinoma. Radiat Oncol 5:41

Michelson H, Bolund C, Nilsson B, Brandberg Y (2000) Health-related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30--reference values from a large sample of Swedish population. Acta Oncol 39(4):477–484

Schwarz R, Hinz A (2001) Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer 37(11):1345–1351

Fakhrian K, Sauer T, Dinkel A, Klemm S, Schuster T, Molls M, Geinitz H (2013) Chronic adverse events and quality of life after radiochemotherapy in anal cancer patients. A single institution experience and review of the literature. Strahlenther Onkol 189(6):486–494

Vordermark D, Sailer M, Flentje M, Thiede A, Kolbl O (1999) Curative-intent radiation therapy in anal carcinoma: quality of life and sphincter function. Radiother Oncol 52(3):239–243

Bentzen AG, Guren MG, Vonen B, Wanderas EH, Frykholm G, Wilsgaard T et al (2013) Faecal incontinence after chemoradiotherapy in anal cancer survivors: long-term results of a national cohort. Radiother Oncol 108(1):55–60

Das P, Cantor SB, Parker CL, Zampieri JB, Baschnagel A, Eng C, Delclos ME, Krishnan S, Janjan NA, Crane CH (2010) Long-term quality of life after radiotherapy for the treatment of anal cancer. Cancer 116(4):822–829

Marinez AC, Gonzalez E, Holm K, Bock D, Prytz M, Haglind E et al (2016) Stoma-related symptoms in patients operated for rectal cancer with abdominoperineal excision. Int J Color Dis 31(3):635–641

Kasparek MS, Hassan I, Cima RR, Larson DR, Gullerud RE, Wolff BG (2012) Long-term quality of life and sexual and urinary function after abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 55(2):147–154

Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Lindegaard JC, Laurberg S (2015) Urinary and sexual dysfunction in women after resection with and without preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Color Dis 17(1):26–37

Jayne DG, Brown JM, Thorpe H, Walker J, Quirke P, Guillou PJ (2005) Bladder and sexual function following resection for rectal cancer in a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open technique. Br J Surg 92(9):1124–1132

Andersson J, Abis G, Gellerstedt M, Angenete E, Angeras U, Cuesta MA et al (2014) Patient-reported genitourinary dysfunction after laparoscopic and open rectal cancer surgery in a randomized trial (COLOR II). Br J Surg 101(10):1272–1279

Lange MM, van de Velde CJ (2011) Urinary and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment. Nat Rev Urol 8(1):51–57

Tekkis PP, Cornish JA, Remzi FH, Tilney HS, Strong SA, Church JM, Lavery IC, Fazio VW (2009) Measuring sexual and urinary outcomes in women after rectal cancer excision. Dis Colon Rectum 52(1):46–54

Haglind E, Carlsson S, Stranne J, Wallerstedt A, Wilderang U, Thorsteinsdottir T et al (2015) Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction after robotic versus open radical prostatectomy: a prospective, controlled, nonrandomised trial. Eur Urol 68(2):216–225

Funding

Lion’s Cancer Research Fund of Western Sweden, the Swedish Society of Medicine, The Swedish Research Council 2017-01103, The Swedish Cancer Society 2016/509, Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Agreement concerning research and education of doctors ALFGBG-493341 and ALFGBG-426501, The Healthcare Committee, Region Västra Götaland, VGRFOU 569701 and VGRFOU 644421.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anton Sterner and Eva Angenete designed the study; Anton Sterner, Hanna Nilsson and Eva Angenete collected data; Anton Sterner, Hanna Nilsson and Eva Angenete analyzed the data; Anton Stener, Kristoffer Derwinger, Caroline Staff, Hanna Nilsson and Eva Angenete interpreted the results; Anton Sterner, Hanna Nilsson and Eva Angenete drafted the article; Anton Stener, Kristoffer Derwinger, Caroline Staff, Hanna Nilsson and Eva Angenete all critically revised the article and gave final approval for submission.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sterner, A., Derwinger, K., Staff, C. et al. Quality of life in patients treated for anal carcinoma—a systematic literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis 34, 1517–1528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03342-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03342-x