Abstract

Introduction

The open surgical wound is exposed to cold and dry ambient air resulting in heat loss mainly through radiation and convection. This cools the wound and promotes local vasoconstriction and hypoxia. Carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapor are greenhouse gases with a warming effect. The aim was to evaluate if warm humidified CO2 insufflated in surgical wound can affect long-term overall mortality

Methods

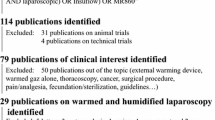

This is a retrospective study of two clinical trials, where patients were randomized to warm humidified CO2 (n = 80) or not (n = 78). All patients underwent elective major open colon surgery. Patients in the treatment group received insufflation of warm humidified CO2 into the open wound cavity via a gas diffuser to create a local atmosphere of 100 % CO2. Temperature in the wound cavity was measured with a heat-sensitive infrared camera. Core temperature was measured at the tympanic membrane. Median follow-up was 70.9 months.

Results

A multivariate analysis adjusted for age (p = 0.001) and cancer (p = 0.165) showed that the larger the temperature difference between final core temperature and wound edge temperature, the lower the overall survival rate (p = 0.050). Patients receiving insufflation of warm humidified CO2 had a tendency to a better overall survival compared with control patients (p = 0.508). End-of-operation wound edge temperature was negatively associated with mortality (OR = 0.80, 95 % CI = 0.68-0.95, p = 0.011), whereas mortality was positively associated with age (10-year increase, OR = 1.78, 95 % CI = 1.37-2.33, p < 0.001) and cancer (OR = 8.1, 95 % CI = 1.95–33.7, p = 0.004).

Conclusions

A small end-of-operation temperature difference between final core and wound edge temperature was positively associated with patient survival in open colon surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Open colorectal surgery under general anesthesia almost always results in intraoperative hypothermia. This is due to anesthesia-induced thermoregulatory inhibition combined with exposure to a cold operating room environment [1]. Heat loss through convection and radiation accounts for the majority of the total perioperative heat loss. A large open surgical wound will amplify evaporation and radiation from the exposed surfaces of the internal organs. Hypothermia is traditionally defined as a core temperature of <36.0 °C [2], and perioperative core hypothermia increases the risk of surgical wound infection [3–5], as a consequence of decreased local tissue blood flow and tissue oxygenation [6, 7]. Also, it impairs immune function [8, 9], increases perioperative bleeding and transfusion requirements [10], enhances the incidence of postoperative shivering and morbid cardiac events [11], and it prolongs hospital stay and increases costs. Current guidelines [2, 12–14] therefore recommend active counter measures to maintain normothermia, including passive insulation and, active transfer of heat to the body with resistive-heating or forced-air warming blankets, as well as fluid warming systems. However, more than one third of general surgery patients undergoing open abdominal operations have been reported to be hypothermic on arrival in the postoperative care unit [14, 15].

Warming the open surgical wound by local insufflation of warmed humidified carbon dioxide (CO2) during colorectal surgery has been shown to significantly increase both core and wound temperatures in two randomized clinical trials [16, 17]. The creation of a CO2-saturated atmosphere within the surgical wound cavity offers unique possibilities, because CO2 acts like a greenhouse gas that will trap heat radiating from the organ surfaces and decrease evaporative heat loss and convection resulting from the operating room ventilation [18, 19]. Furthermore, locally applied CO2 is known to cause vasodilatation of micro vessels in the skin and muscular arterioles [20], leading to increased local tissue perfusion in the surgical wound.

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether increased wound and core temperatures during major open colorectal surgery induced by local insufflation of warm humidified CO2 is related to long-term overall morbidity and mortality.

Methods

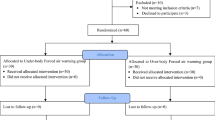

This study is a post hoc retrospective single-center study of two clinical trials where patients were randomized to a warm humidified CO2 group (n = 80) or a control group (n = 78). All included patients underwent elective major open colon surgery between March 2007 and November 2013 at Karolinska University Hospital. For this type of study, formal consent is not required. Postoperative morbidity and mortality were obtained May 2015, from the hospital’s medical records that are linked to the national Swedish database on mortality, the Total Population Registry (Approved by the Regional Ethical Committee in Stockholm, 2015/1063-32). None of the patients were lost to follow-up. Patients randomized to the treatment group received insufflation of warm humidified CO2 into the open wound cavity via a humidification system and a gas diffuser (Carbon Vita®, Cardia Innovation AB, Stockholm, Sweden). In the first trial [17], a noncommercial system that delivered humidified CO2 at 93 % relative humidity and 30 °C (n = 80) was used, whereas in the second trial [16], a commercial system delivered 100 % relative humidity and 37 °C (n = 78) to the surgical wound (HumiGard™, Fisher & Paykel HealthCare Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand). All but 10 patients (6 %) received a thoracic epidural blockade in addition to general anesthesia. The temperature in the wound cavity was measured every 10 min with a heat-sensitive infrared camera (ThermaCAM™ B2, FLIR Systems AB, Danderyd, Sweden). Core temperature was measured in degrees Celsius at the tympanic membrane every 30th minute by a thermometer (CORE-CHECK™ Tympanic Thermometer System, Cardinal Health, Dublin, OH) from the time that the patient was anesthetized until the end of surgery. Further details regarding the trials were previously published [16, 17]. In addition to the exclusion criteria described [16, 17], patients who underwent colostomy surgery were excluded since the focus was on major colon surgery.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as numbers and percentages. Survival in the CO2 group and the treatment group, as well as final core temperature ≥36.0 °C, respectively, was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves. To identify variables associated with mortality, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed. The relationship between core and wound edge temperature differences at the end of surgery, and mortality, was analyzed using the Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age and cancer. The p values for the differences in patient characteristics were obtained by chi-square or t tests. SPSS software (version 22, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) was used for statistical analyses. All tests were two-sided. Statistical significance was accepted for p values ≤0.05.

Results

The total study population comprised of 91 men and 67 females with a median age of 63 years. Median follow-up was 70.9 months, and no patients were lost to follow-up. Preoperative patient characteristics did not differ significantly between the treatment groups Table 1.

All temperatures at the end of surgery as well as the temperature differences between core and wound were significantly higher in the CO2 group. Mean operating time was 218 min in both groups, and all remaining end points tended to be in favor of the CO2 group (Table 2; peri- and postoperative end points).

Of the 158 patients, 117 (74 %) patients underwent open colon/rectal cancer surgery, with the remainder operated on for inflammatory bowel disease involving the colon. Forty-one (26 %) died during the complete follow-up period including 3 patients (2 %) who died within 30 days of the operation. Primary causes of death (disease or condition directly leading to death) within 30 days were cardiovascular (n = 3), whereas the primary causes of death after 30 days were cancer (n = 20), cardiovascular (n = 7), ileus (n = 1), renal insufficiency (n = 1), sepsis (n = 1), and unknown (n = 8).

Patients receiving insufflation of warm humidified CO2 had a tendency to a better overall survival compared with control patients (p = 0.508). Figure 1 depicts the survival in the CO2 group and the treatment group in all subjects. Patients with a core temperature ≥36.0 °C at the end of surgery exhibited a better overall survival compared with those with core temperature <36.0 °C at the end of surgery (OR 0.5, 95 % CI 0.26-096, p = 0.035), Fig. 2.

Overall univariate mortality predictions for all patients during elective major open colon cancer surgery are shown in Table 3. As expected, age and cancer showed a strong association with mortality (p = <0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively). Moreover, a final core temperature ≥36.0 °C (p = 0.035) and a higher final wound edge temperature (p = 0.011) were associated with lower mortality, whereas a smaller difference between final core and final wound edge temperature (p = 0.017) improved survival. A multivariate analysis (Table 3) adjusted for age (p = 0.001) and cancer (p = 0.165) showed that the temperature difference between final core and final wound edge temperature was associated with a better overall survival (p = 0.050).

Discussion

This is a hypothesis-generating, retrospective single-center study following two smaller randomized trials. This work has shown that long-term mortality is associated with core and wound edge temperatures at the end of major open colorectal surgery as well as to age and cancer diagnosis. The difference between core and wound edge temperature at end of surgery significantly influenced mortality in a multivariate model, when controlling for age and cancer diagnosis. Insufflation of warmed humidified CO2 in the open surgical wound increased final core and wound temperatures during surgery but did not significantly affect mortality.

The potential ability of increased wound temperature to improve long-term survival after major open colon surgery can be attributed to at least three different mechanisms.

First, perioperative hypothermia has been demonstrated to lead to increased cardiac demand and, subsequently, increased risk of cardiac morbidity [21]. Patients who survived a postoperative cardiac event continued to be at a considerable risk of cardiac death, with a hazard ratio of 18 (95 % CI, 6–57) in the first 6 month after discharge. In patients with cardiac risk factors who are undergoing noncardiac surgery, the perioperative maintenance of normothermia is associated with a reduced incidence of morbid cardiac events and ventricular tachycardia [11]. These numbers are consistent with our findings that patients with a core temperature ≥36.0 °C at the end of surgery exhibited a significantly better overall survival compared with those with core temperature <36.0 °C at the end of surgery. Also, the treatment group with insufflation of warm humidified CO2 tended to have a better longtime survival, although this did not reach significance, possibly due to a type II error.

Second, insufflation of warm humidified CO2 in the open surgical wound increased core and wound temperatures and decreased the difference between core and wound temperatures. These changes may indicate a better perfusion and a better oxygenation of the open surgical wound, where wound edge temperature is a more sensitive indicator of wound tissue perfusion than wound area, since the latter temperature is influenced by all exposed internal tissues. A recently published rat model showed that insufflation of warm humidified CO2 into the abdominal cavity during open abdominal surgery caused a rapid increase in wound tissue oxygen tension [22]. The humidification and warming to physiological temperature of the insufflated CO2 decrease desiccation from the open wound and increase overall wound temperature thereby improving general wound perfusion and oxygenation.

Third, preventing desiccation of the exposed peritoneal mesothelium by insufflation of warm humidified CO2 has been shown to reduce intraperitoneal tumor dissemination in animal models, a finding which is consistent with maintaining the physiological integrity of the mesothelium as an intact barrier to tumor infiltration [23, 24]. The peritoneum was the sole site of metastasis in >50 % of patients with metastatic disease [25], and such metastasis remains fatal [26]. This could have impacted the long-term survival in our study.

Potential limitations are that this was a retrospective post hoc study of postoperative morbidity and mortality, although patients had been randomized before surgery. Potentially relevant data are missing in the records such as prospective evaluation of wound infections. Moreover, the study is relatively small with a concurrent probability of type II errors. Also, two different heating systems were used in the study.

The strength of the study is that the long-term effects of intraoperative wound area and wound edge temperatures have to our knowledge not been studied before. Importantly, patients were warmed with standard warming measures according to the NICE guidelines [2]. In addition, 94 % of the patients received epidural analgesia together with general anesthesia, and this combination has been shown to increase long-term survival after colon surgery in a retrospective study [27], which could be due to a reduction in neuroendocrine response and attenuated immunosuppression. Furthermore, none of our patients were lost to follow-up.

In conclusion, our study shows that insufflation of warm humidified CO2 into the open wound significantly increases wound and core temperatures. Normothermia at end of surgery as well as a small end-of-operation temperature difference between final core and wound edge temperature was significantly associated with better patient survival in open colon surgery. Moreover, patients with a core temperature ≥36.0 °C at end of surgery exhibited a better overall survival compared with those with core temperature <36.0 °C.

References

Sessler DI (2008) Temperature monitoring and perioperative thermoregulation. Anesthesiology 109:318–38

NICE clinical guideline 65 (2010) Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London

Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R (1996) Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. N Engl J Med 334:1209–15

Melling AC, Ali B, Scott EM, Leaper DJ (2001) Effects of preoperative warming on the incidence of wound infection after clean surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 358:876–80

Sessler DI (2001) Complications and treatment of mild hypothermia. Anesthesiology 95:531–43

Greif R, Akca O, Horn EP, Kurz A, Sessler DI (2000) Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection. Outcomes Research Group. N Engl J Med 342:161–7

Sheffield CW, Sessler DI, Hopf HW MS, Moayeri A, Hunt TK, West JM (1996) Centrally and locally mediated thermoregulatory responses alter subcutaneous oxygen tension. Wound Rep Reg 4:339–45

Beilin B, Shavit Y, Razumovsky J, Wolloch Y, Zeidel A, Bessler H (1998) Effects of mild perioperative hypothermia on cellular immune responses. Anesthesiology 89:1133–40

Wenisch C, Narzt E, Sessler DI, Parschalk B, Lenhardt R, Kurz A, Graninger W (1996) Mild intraoperative hypothermia reduces production of reactive oxygen intermediates by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anesth Analg 82:810–6

Rajagopalan S, Mascha E, Na J, Sessler DI (2008) The effects of mild perioperative hypothermia on blood loss and transfusion requirement. Anesthesiology 108:71–7

Frank SM, Fleisher LA, Breslow MJ, Higgins MS, Olson KF, Kelly S, Beattie C (1997) Perioperative maintenance of normothermia reduces the incidence of morbid cardiac events. A randomized clinical trial. Jama 277:1127–34

Frank SM, Higgins MS, Breslow MJ, Fleisher LA, Gorman RB, Sitzmann JV, Raff H, Beattie C (1995) The catecholamine, cortisol, and hemodynamic responses to mild perioperative hypothermia. A randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 82:83–93

Sessler DI (2009) New surgical thermal management guidelines. Lancet 374:1049–50

Forbes SS, Eskicioglu C, Nathens AB, Fenech DS, Laflamme C, McLean RF, McLeod RS (1996) Evidence-based guidelines for prevention of perioperative hypothermia. J Am Coll Surg 209:492–503

Hedrick TL, Heckman JA, Smith RL, Sawyer RG, Friel CM, Foley EF (2007) Efficacy of protocol implementation on incidence of wound infection in colorectal operations. J Am Coll Surg 205:432–8

Frey JM, Janson M, Svanfeldt M, Svenarud PK, van der Linden JA (2012) Local insufflation of warm humidified CO(2) increases open wound and core temperature during open colon surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg 115:1204–11

Frey JM, Janson M, Svanfeldt M, Svenarud PK, van der Linden JA (2012) Intraoperative local insufflation of warmed humidified CO(2) increases open wound and core temperatures: a randomized clinical trial. World J Surg 36:2567–75

Frey JM, Svegby HK, Svenarud PK, van der Linden JA (2010) CO2 insufflation influences the temperature of the open surgical wound. Wound Repair Regen 18:378–82

Persson M, Elmqvist H, van der Linden J (2004) Topical humidified carbon dioxide to keep the open surgical wound warm: the greenhouse effect revisited. Anesthesiology 101:945–9

Minamiyama M, Yamamoto A (2010) Direct evidence of the vasodilator action of carbon dioxide on subcutaneous microvasculature in rats by use of intra-vital video-microscopy. J Biorheology 24:42–46

Devereaux PJ, Goldman L, Cook DJ, Gilbert K, Leslie K, Guyatt GH (2005) Perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a review of the magnitude of the problem, the pathophysiology of the events and methods to estimate and communicate risk. CMAJ 173:627–34

Marshall JK, Lindner P, Tait N, Maddocks T, Riepsamen A, van der Linden J (2015) Intra-operative tissue oxygen tension is increased by local insufflation of humidified-warm CO2 during open abdominal surgery in a rat model. PLoS ONE 10(4):e0122838

Binda MM, Corona R, Amant F, Koninckx PR (2014) Conditioning of the abdominal cavity reduces tumor implantation in a laparoscopic mouse model. Surg Today 44:1328–35

Carpinteri S, Sampurno S, Bernardi MP, Germann M, Malaterre J, Heriot A, Chambers BA, Mutsaers SE, Lynch AC, Ramsay RG (2015) Peritoneal tumorigenesis and inflammation are ameliorated by humidified-warm carbon dioxide insufflation in the mouse. Ann Surg Oncol. [Epub ahead of print].

Segelman J, Granath F, Holm T, Machado M, Mahteme H, Martling A (2012) Incidence, prevalence and risk factors for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 99:699–705

Kerscher AG, Chua TC, Gasser M, Maeder U, Kunzmann V, Isbert C, Germer CT, Pelz JO (2013) Impact of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the disease history of colorectal cancer management: a longitudinal experience of 2406 patients over two decades. Br J Cancer 108:1432–9

Vogelaar FJ, Abegg R, van der Linden JC, Cornelisse HGJM, van Dorsten FRC, Lemmens VE, Bosscha K (2015) Epidural analgesia associated with better survival in colon cancer. Int J Colorect Dis 30:1103–07

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Frey, J., Holm, M., Janson, M. et al. Relation of intraoperative temperature to postoperative mortality in open colon surgery—an analysis of two randomized controlled trials. Int J Colorectal Dis 31, 519–524 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2467-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2467-4