Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of initialised decadal hindcasts of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre (SPG) using the HiGEM model, which has a nominal grid-spacing of 90 km in the atmosphere, and 1/3\(^{\circ }\) in the ocean. HiGEM decadal predictions (HiGEM-DP) exhibit significant skill at capturing 0–500 m ocean heat content in the SPG, and outperform historically forced transient integrations and persistence for up to a decade ahead. An analysis of case-studies of North Atlantic decadal change, including the 1960s cooling, the mid-1990s warming, and the post-2005 cooling, show that changes in ocean circulation and heat transport dominate the predictions of the SPG. However, different processes are found to dominate heat content changes in different regions of the SPG. Specifically, ocean advection dominates in the east, but surface fluxes dominate in the west. Furthermore, compared to previous studies, we find a smaller role for ocean heat transport changes due to ocean circulation anomalies at the latitudes of the SPG, and, for the 1960s cooling, a greater role for surface fluxes. Finally, HiGEM-DP predicts the observed positive state of the North Atlantic Oscillation in the early 1990s. These results support an important role for the ocean in driving past changes in the North Atlantic region, and suggest that these changes were predictable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There is substantial evidence that links changes in North Atlantic Sea Surface Temperature (SST) to important climate impacts, including the numbers of hurricanes (Goldenberg et al. 2001; Zhang and Delworth 2006; Smith et al. 2010), and the surface climate over the surrounding continents (Sutton and Hodson 2005; Zhang and Delworth 2006; Knight et al. 2006; Sutton and Dong 2012). Therefore, providing predictions of how Atlantic SSTs might evolve over the years-to-decades ahead is an important challenge for climate prediction. Encouragingly, the North Atlantic, and particularly the North Atlantic subpolar gyre (SPG), is a region where hindcasts (or retrospective climate predictions), which are initialised from observations, are found to have significant skill in capturing past variations of SST (Smith et al. 2010; García-Serrano et al. 2012; Matei et al. 2012; Doblas-Reyes et al. 2013; Kirtman et al. 2013; Shaffrey et al. 2016). However, in order to build confidence that future predictions will remain skillful, it is important to understand why hindcasts are successful, and if the dominant mechanisms are robust.

An important method for understanding the sources of skill in initialised climate predictions has been a focus on specific case studies of large decadal change. Process based analysis of hindcasts has shown that skill is not simply due to the thermal inertia of the SPG. Rather, the initialisation of ocean circulation played an important role for hindcasts to capture the major shifts in the SPG heat content (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012; Msadek et al. 2014; Robson et al. 2014b). For example, an initialisation of a weak Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and related weak ocean heat transports was important for capturing the cooling of the SPG in the late 1960s (Robson et al. 2014b). Furthermore, the initialisation of the ocean circulation, in particular a strong AMOC, in the early 1990s also appears to be important for capturing the mid-1990s warming (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012; Msadek et al. 2014; Monerie et al. 2017) and the subsequent weakening of the SPG (Msadek et al. 2014). Both the 1960s and 1990s events were also associated with significant shifts in observed surface climate over land (Sutton and Dong 2012; Hodson et al. 2014)—aspects of which appear to be captured in these case-studies (Robson et al. 2013, 2014b; Msadek et al. 2014; Müller et al. 2014).

Although there is significant skill at capturing previous shifts in North Atlantic temperatures in current prediction systems, there are still significant uncertainties. In particular, the number of well-observed case-studies of decadal change in the North Atlantic is limited. Moreover, only a few studies have explored the mechanisms behind the successful predictions in the North Atlantic and, to date, these studies have usually just focused on the 1990s warming (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012; Msadek et al. 2014; Monerie et al. 2017). The majority of models used for initialised climate prediction have also used low-resolution models (ocean resolution >1\(^{\circ }\)), which may not capture all the relevant processes in the North Atlantic. Indeed, evidence suggests that the strength of ocean-atmosphere coupling (Bryan et al. 2010), and the time-scales of ocean adjustment (Getzlaff et al. 2005; Hodson and Sutton 2012), may differ in high-resolution models compared to low-resolution. The presence of ocean eddies may also influence the dominant mechanisms of variability Volkov et al. (2008); Marzocchi et al. (2015). Therefore, in order to ensure that the best information is available to assess the robustness of predictions, and to guide model development, it is important to understand the sensitivity of skill and mechanisms to the underlying model used. The need for further understanding is especially clear given that a decadal time-scale weakening of the AMOC appears to be underway (Smeed et al. 2013; Robson et al. 2014a), and many studies are now predicting a cooling of the North Atlantic, which may have important climate impacts (Hermanson et al. 2014; Kloewer et al. 2014; McCarthy et al. 2015; Yeager et al. 2015; Robson et al. 2016).

In this paper we will explore the origin of skill in the North Atlantic in HiGEM decadal predictions [henceforth HiGEM-DP, Shaffrey et al. (2016)]. HiGEM has an eddy permitting ocean model and has an improved simulation of many aspects of the climate, including reduced biases in the North Atlantic (Shaffrey et al. 2009). Shaffrey et al. (2016) has already highlighted that HiGEM possesses substantial skill in predicting SST in the North Atlantic region. This paper will expand on the analysis of Shaffrey et al. (2016) and will use novel heat budget analysis on a range of specific case-studies to understand the physical mechanisms responsible for the improvements in skill in the North Atlantic.

The paper is set out as follows: Sect. 2 presents a brief overview of the HiGEM-DP and details of the analysis. The analysis of HiGEM-DP predictions are presented in Sect. 3, before discussion in Sect. 4. Finally, conclusions are presented in Sect. 5.

2 HiGEM-DP and analysis methods

2.1 Overview of HiGEM-DP

HiGEM-DP is based on initialising the HiGEM coupled climate model from the observed state of the climate system. The HiGEM model is a high-resolution version of the HadGEM1 model (Johns et al. 2006), and was jointly developed between UK academia and the UK Met Office (Shaffrey et al. 2009). The ocean model is based on a Bryan-Cox code (Bryan 1969; Cox 1984), and is based on the ocean component used in HadCM3 (Gordon et al. 2000). The ocean model in HiGEM has a resolution of 1/3\(^{\circ }\) \(\times \) 1/3\(^{\circ }\) on a latitude-longitude grid, and has 40 vertical levels that increase in thickness smoothly from 10 m at the ocean surface to 300m at depth. The atmospheric model resolution is 1.25\(^{\circ }\) \(\times \) 0.83\(^{\circ }\) (nominally \(\sim \)90 km in the extra-tropics) and has 38 vertical levels, with a level top at 39 km. The ice model in HiGEM is based on the Community Ice Code (CICE) elastic-viscous-plastic model (McLaren et al. 2006). For more details on the scientific construction of HiGEM the reader is referred to Shaffrey et al. (2009).

We now briefly summarise how HiGEM was initialized with observations; for further details the reader is referred to Shaffrey et al. (2016). HiGEM-DP uses an “anomaly assimilation” technique similar to that used in Smith et al. (2007). Ocean observations are introduced to the model by relaxing a fully coupled integration of HiGEM towards a gridded analysis of ocean observations of potential temperature and salinity (this experiment is referred to as the “assimilation” run). Specifically, the model is relaxed towards the observed monthly-mean anomalies derived from the UK Met Office statistical ocean reanalysis MOSORA data set (Smith and Murphy 2007; Smith et al. 2015). The observed monthly-mean anomalies are added to a monthly varying HiGEM climatology that was computed from a present day control run (i.e. with fixed boundary conditions that are representative of the 1990s). Due to the use of the present day control run for the model climatology, the observational climatology was chosen to be 1985–2005 to reflect a period of similar boundary conditions (i.e. greenhouse gases, aerosols etc). A 15-day relaxation time was chosen for the assimilation. Note that the atmosphere is not constrained by observations and is free to evolve and adjust to the ocean assimilation and historical forcings.

Hindcasts with HiGEM-DP followed the CMIP5 protocol with hindcasts started every 5 years from 1960 to 2005 (i.e. 1960, 1965, 1970...., 2005; these hindcasts will be referred to as the CMIP5 set). Hindcasts were started on November 1st, and a 4 member ensemble was generated by using lagged atmospheric initial conditions (i.e. atmospheric conditions which span the 1st–4th of November). Hindcasts were integrated for 10 years, and forced with historical changes in external forcings (greenhouse gases, anthropogenic and volcanic aerosols, and solar). Following 2005, hindcasts were forced with the RCP4.5 emissions scenario.

To be able to understand the impact of initialisation on HiGEM-DP hindcasts, an ensemble of 4 historical transient runs were also performed with HiGEM (referred to at the transient runs). Due to the computational expense, the transient runs were started in the late 1950s rather than from pre-industrial conditions. Specifically, 4 different initial conditions taken from the end of a 65-year constant forcing experiment with historical forcings (greenhouse gases, aerosols, solar and ozone) at an average of 1955–1960 taken from CMIP3. The general performance of HiGEM-DP was presented in Shaffrey et al. (2016).

To examine the ability of HiGEM to capture the evolution of the SPG in the 1990s and 1960s we have also performed additional experiments. Hindcasts are initialised every year between 1990–1995, and additional hindcasts are also performed in 1966 and 2004 and 2006. This gives a total 17 hindcasts overall, each with 4 members. Finally, for the purpose of examining the surface climate impacts in the hindcasts two additional transients were spun off in 1979 (i.e. giving a total ensemble of 6 transient runs for the satellite period 1979-present). However, the data from these additional experiments (hindcasts and transient runs) will only be used when examining the climate impacts in Fig. 7.

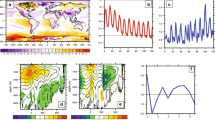

The ensemble-mean predictions of SPG 0–500 m heat content and skill. a Shows seasonal-mean 0–500 m average temperature anomalies averaged over the North Atlantic subpolar gyre region (50–65\(^{\circ }\)N,60–10\(^{\circ }\)W) for HiGEM-DP (red and orange alternating) and the HiGEM historical transient runs (1-year smoothed ensemble mean shown by the blue line, and shaded region shows the average 1\(\sigma \) spread calculated from seasonal anomalies). Black line shows the same for the observations from EN4 ocean analysis. All anomalies are made relative to the 1961–2012 period, where HiGEM-DP anomalies are defined using a time-invariant climatology computed from the assimilation run. b Shows the same but after a lead-time dependent mean-bias is removed from the HiGEM-DP hindcasts. c Shows the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) skill score for the CMIP5 start dates (1960, 1965,...2005 ) for HiGEM-DP (red), the transient runs (blue) and persistence (purple) as a function of prediction lead time. Red diamonds show where the ACC for HiGEM-DP is significantly different to the ACC of the transient runs at the p \(\le \) 0.05 based on a one-sided Monty-Carlo test (see text for details). d Shows the spread-error ratio (SER) as a function of lead-time for HiGEM-DP (red) and the transient runs (blue). SER values above (below) 1 indicate that predictions are under-confident (overconfident). Diamonds on panel d show where the SER is significantly different from 1 at the p \(\le \) 0.1 based on a Jackknife re-sampling (see text for details)

2.2 Data and analysis methods

Where possible we compare HiGEM-DP to observations. For subsurface ocean temperatures we use the EN4.0.2 data set (Good et al. 2013). For Sea Level Pressure (SLP) we use HadSLP2 (Allan and Ansell 2006). Surface Air Temperature (SAT) and Sea Surface Temperature (SST) is taken from HadCRUT4.3 (Morice et al. 2012) and HadISST (Rayner et al. 2003), respectively. For analysis of spatial fields (e.g. Figs. 5, 6 and 7) HiGEM data has been re-gridded to the lower resolution of the observed data sets. Ocean variables are re-gridded to a 1 \(\times \) 1\(^{\circ }\) grid used by EN4, and atmospheric fields are re-gridded to the 5 \(\times \) 5\(^{\circ }\) grid used by HadCRUT4.3.

Skill for predictions of subpolar gyre heat content is evaluated using the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient skill score (ACC). To test the significance of the ACC we use a similar method to that used in Shaffrey et al. (2016). We create synthetic sections of the transient runs by using a Monty-Carlo block-bootstrapping approach. Specifically, we generate a time-series of perturbations by randomly sampling a continuous 10-year block from all transient errors (i.e. the transient anomalies minus the observations, for all four transient runs over the period 1960–2014) based on the SPG time-series. For each Monty-Carlo iteration (n), we re-sample the errors for each transient run separately (i.e. four times in total), and for each HiGEM-DP start date. These perturbations are then added to the relevant section of the transient runs independently, and the ACC is then recalculated. A distribution of ACCs for the transient runs is computed based on a total of \(n=\) 1000 iterations. The ACC HiGEM-DP is considered significant if it is larger than the 95th percentile of the transient ACC distribution.

For a prediction system to be useful it is also important that predictions are reliable (Corti et al. 2012; Ho et al. 2013). Therefore, we also evaluate the dispersion characteristics of HiGEM-DP to give a simple metric of the reliability (Ho et al. 2013). Specifically we compute the spread-error ratio (SER), which is the ratio of the mean intra-ensemble standard-deviation to the root mean squared error (RMSE) as a function of lead-time [see Eq. 1 in Ho et al. (2013)]. The RMSE is calculated for the ensemble-mean anomaly after a mean-bias correction has taken place. A correction for small ensemble sizes is also applied [see Ho et al. (2013) for details]. If the SER is greater (smaller) than one, then the predictions are over-dispersed (under-dispersed) and will be under-confident (over-confident). We test the significance of the SER through a Jackknife procedure where we randomly exclude an ensemble member from each start-date before calculating both the intra-ensemble spread and RMSE. A distribution of Jackknife re-sampled SER is calculated based on a total of \(n=\) 1000 iterations, and the SER is considered significant if 1 falls outside the 5–95 percentiles.

As shown in Shaffrey et al. (2016), HiGEM-DP develops a systematic bias, or drift, in SST (see their Fig. 3). Therefore, in order to remove a lead-time dependent drift, variables are made relative to a hindcast-mean climatology, in a manner similar to Msadek et al. (2014).Footnote 1 That is, for each lead-time, the climatology is defined as the mean of all of the CMIP5 HiGEM-DP hindcasts, giving an average of 40 individual experiments (i.e. 10 starts with 4 members). For the transient runs we computed a time-invariant climatology by sampling the same years used to compute the lead-time dependent hindcast climatology (1961–2014). Note that the results were not found to be sensitive to using a lead-time dependent climatology for the transient runs. Additionally we note that HiGEM-DP also exhibits a non-linear start-date dependent adjustment, or drift, of the AMOC (Shaffrey et al. 2016). We do not attempt to remove start-date dependent drift from the hindcasts, but, the impact of this ’residual’ drift will be discussed for specific case studies.

The hindcast-mean bias and heat budget for the SPG in the 10 CMIP5 HiGEM start-dates. a Shows the seasonal-mean lead-time dependent hindcast-bias (black solid), and the lead-time dependent hindcast climatology now relative to the lead-time invariant 1985–2006 climatology used in the “assimilation” run (black dashed). b Shows the monthly-mean heat-fluxes into the upper 0–500 m of the subpolar gyre (50–65\(^{\circ }\)N, 60–10\({^{\circ }}\)W) averaged over all 10 CMIP5 start dates. The components shown are:- ocean advection and diffusion (blue), surface fluxes (purple), convection and mixed layer (red) and sea ice (yellow). c Shows the same as (b) but now for the 12-month running-mean of the anomalies, where anomalies are relative to the mean of all 10-years from (b). The sum of all the anomalous fluxes is also shown (blue dash). Finally, the 12-month running-mean of the monthly change in ocean heat content in this region, averaged over all 10 CMIP5 hindcasts and expressed in J s\(^{-1}\), is shown for comparison (black dashed); note that blue and black dash are almost identical, showing that the heat budget is closed

Previous studies used simplified heat budgets to understand initialised predictions of the SPG (Robson et al. 2012b, 2014b). We build on these studies by making use of three-dimensional ocean heat budget terms available in HiGEM (Kuhlbrodt et al. 2015). At each time-step, the temperature tendency in each grid-box due to ocean advection, diffusion (calculated as individual terms for x, y and z), convection, mixed layer physics, sea-ice physics, incoming solar, and the other surface heat fluxes (i.e. sensible, latent, and longwave) is calculated, and output in monthly-mean fields. We combine the fluxes into Ocean Advection (i.e. the sum of advection and diffusion), Surface Fluxes (i.e. including solar), Convection and Mixed layer, and Sea-Ice physics.Footnote 2 Note that there is no Gent-McWilliams parametrization in HiGEM (Shaffrey et al. 2009). Therefore, the advection component also includes advection due to the partially resolved ocean eddies (Kuhlbrodt et al. 2015).

To understand the changes in ocean heat transports we also examine changes in basin wide meridional heat transport (MHT). The total MHT, and its geometric decomposition into vertical and horizontal heat transports [commonly assumed to represent “overturning” or “gyre” heat transports, respectively, Bryan (1969)], is calculated by the model at each time-step. We also further decompose the MHT, as in previous studies (Robson et al. 2012a, 2012b, 2014b), into the component that is associated with changes in the strength of the ocean circulation (i.e. \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\)), and MHT due the advection of temperature anomalies by the mean circulation (i.e. \(\bar{v}T^{\prime }\)), and the covariance of both circulation and temperature anomalies (i.e. \(\upsilon^{\prime }T^{\prime }\)), based on Eq. 1 in Dong and Sutton (2002). These terms are calculated “offline” using three-dimensional monthly-mean temperature and meridional velocity fields. For this calculation we used a climatology computed from the present day control run to express temperature and velocity anomalies. As we are limited to the use of monthly-mean data, rather than time-step data as used by the model, we first compare the total MHT calculated in the two ways. Specifically, we compare total MHT calculated “offline” against that calculated by the model at each time-step. The correlation between the annual-mean total MHT averaged between 35–65\(^{\circ }\)N calculated offline and online is high (r = 0.99) when averaged over all hindcasts. Therefore, we conclude that the variability in MHT is adequately captured by the offline MHT diagnostics.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of SPG prediction skill, bias and the climatological heat budget

The time series of SPG (60–10\(^{\circ }\)W, 50–65\(^{\circ }\)N) 0–500 m average temperature for the HiGEM-DP CMIP5 hindcasts, relative to a time-invariant climatology, is shown in Fig. 1. For clarity we only show the ensemble mean of the hindcasts (the individual ensemble members for the 1965, 1995 and 2005 hindcast are shown in Fig. 3), and we smooth the transient runs with a 1-year running-mean. HiGEM-DP is, generally, able to capture 0–500 m average temperature in the SPG with good skill (see Fig. 1c). Hindcasts capture the cooling of the SPG in the mid-1960s, the relatively cool temperatures in the 1970s and 1980s, and the abrupt warming in the mid 1990s. The hindcast initialised in 2005 also appears to capture the subsequent cooling trend. The resulting anomaly correlation skill score (ACC) for HiGEM-DP is \(\sim \)0.9 for the first year, similar to the skill found due to persistence. However, HiGEM-DP substantially outperforms persistence at longer lead-times; the ACC for HiGEM-DP remains above 0.7 for all lead-times, but the ACC for persistence is zero by lead-time 6–8. HiGEM-DP also significantly outperforms the transient runs at all lead-times.

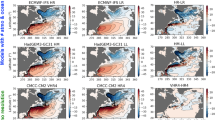

Subpolar gyre heat budgets for the 1965, 1995 and 2005 HiGEM hindcasts. a Time-series of 0–500 m temperature anomalies in the North Atlantic SPG, as Fig. 1, but now only showing the 1965 HiGEM-DP hindcast. Thick red line shows the ensemble mean, and thin lines show the individual ensemble members. b, c show the same as (a), but now for the 1995 and 2005 hindcasts. d Shows the heat content change due to ocean advection and diffusion (blue, advec), surface fluxes (purple, sflux), convection and mixed layer (red, convec), and ice (yellow) for the HiGEM-DP 1965 hindcast. Crosses and diamonds show the integrated change in heat content in corresponding section of the transient run for lead year 5 and 10, respectively. e, f Show the same as (d), but for the 1995 and 2005 hindcasts. g Shows the anomalous 3-year-mean heat fluxes in the hindcasts integrated over the SPG. h and i Show the same as (g) but now for the 1995 and 2005 hindcast. Circles show the fluxes are significantly different to the transients at the p \(\le \) 0.1, based on a Student’s T-test

The spread-error ratio for HiGEM-DP predictions of the 0–500 m average SPG temperature anomaly is smaller than one for the first year (see Fig. 2d), which is not surprising given the simple initialisation procedure for HiGEM-DP. However, SER is not statistically different to 1 for lead-times longer than one year (see Fig. 1d). Therefore, we conclude that HiGEM-DP is generally able to produce reliable predictions of the SPG 0–500 m heat content. On the other hand there is also some evidence that the HiGEM transients are under-dispersed (or over confident), although these results are also generally not significant. We find that the RMSE for the transient runs are comparable to those computed for a climatological prediction (not shown). Therefore, the over-confidence of the transient runs suggests that HiGEM underestimates the variability of the SPG 0–500 m heat content over the observed period. We also find that the observed and transient run SPG variability is also significantly different at the p \(\le \) 0.05 (based on an F-test) when using all the years available from 1960 on wards. However, more start-dates and ensemble members, as well as understanding the sensitivity to the observations used, will be needed to fully understand the SER for predictions of SPG 0–500 m heat content with HiGEM.

Although HiGEM-DP skillfully captures the evolution of 0–500 m heat content in the SPG, hindcasts do not perfectly capture the observed time-series. For example, the 1965 and 1970 hindcasts warm abruptly following a lead time of \(\sim \)5 years. The mean hindcast-bias of the 10 CMIP5 hindcasts [i.e. the average difference between predicted and observed 0–500 m temperature anomalies as a function of lead-time; see Eq. 1 in Smith (2013)] is shown in Fig. 2a (solid line). In general, HiGEM-DP predicts 0–500 m SPG heat-content that is too cool up to \(\sim \)lead-year 4. After year 4 the hindcast-bias begins to reduce and becomes positive after lead-year 8. As the ACC skill score is not sensitive to hindcast-bias (Smith 2013), we also show the 0–500 m average temperatures after the hindcast-bias in Fig. 2a is removed (see Fig. 1b). However, although the hindcasts are sensitive to this hindcast-bias correction the overall evolution does not change (i.e. cooling in the 1960s, warming in the 1990s, and cooling following 2005).

Atlantic meridional heat transport (MHT) anomalies in the 1965, 1995 and 2005 HiGEM hindcasts as a function of prediction lead-time. a Shows the MHT anomaly in the HiGEM-DP prediction started in 1965 as a function of latitude-vs-time [10\(^{14}\) W]. b, c Shows the same as (a) but now for the MHT anomaly that is associated with the anomalous ocean velocities, and the anomalous temperature anomalies respectively. d–f, and g–i Shows the same as (a–c) but now for the 1995 and the 2005 start dates. Black dashed lines show where the anomalies are significantly different to the transient anomalies at the p \(\le \) 0.1 level, based on a Student’s T-test

Contributions to 0–500 m ocean heat content change in the 1965, 1995 and 2005 hindcasts. a Shows the ensemble-mean heat content change due to ocean advection and diffusion integrated from 1 to year 10 of the HiGEM prediction started in 1965. b, c Shows the same but for surface fluxes and convection. d Shows the ensemble-mean change in heat content in the 1965 start date (e.g. year 10–year 1). Note that to compare with observations, all fluxes (in J s\(^{-1}\)) have been computed as tendencies in \(^{\circ }\)C. e Shows the observed linear trend fitted for the 10-years following 1965. Stippling shows where the magnitude of the linear trend is larger than 2\(\sigma \) of the residuals (f–j), and k–o shows the same as (a–e), but now for the 1995 and 2005 start-dates

To investigate the causes of the lead-time dependent bias in HiGEM-DP, we first compare it with the lead-time dependent hindcast climatology. We do this by making the lead-time dependent hindcast climatology relative to the time-invariant climatology computed from the assimilation run. Figure 2a shows that the lead-time dependent bias and lead-time dependent changes in the hindcast climatology are very similar (note that the bias is more noisy, which is likely due to the influence of the poorly sampled observed variability). Therefore, we conclude that in the SPG the lead-time dependent hindcast-bias is caused by the same processes that cause the lead-time dependent drift in HiGEM-DP. As the hindcast-bias and the hindcast-climatology are so similar, we further examine the lead-time dependent hindcast-climatology to elucidate the processes involved.

We start by first examining the climatology of the SPG heat budget. Figure 2b shows that the 0–500 m SPG heat budget is dominated by a balance between ocean heat transport convergence (i.e. advec) into the SPG, which provides a net warming, and surface fluxes, which provides a net cooling with a strong seasonal peak in March. Sea-Ice (cooling) and convection (warming) play a more minor role in the climatology, with both terms peaking in the winter and spring. We also find that the relative balance of terms changes with hindcast lead-time. Figure 2c shows the lead-time dependent heat flux climatology now expressed relative to its time-mean. The ocean advection term is substantially weaker in the first year when compared to the time-mean (and also when compared to the transients, not shown), which leads to relatively rapid cooling of the SPG within the first year (see Fig. 2c). However, the ocean advection term increases significantly with lead-time (towards the climatology of the transient experiments, not shown) until ocean advection is an anomalous net warming to the SPG from lead-year 4 on wards. The changes in the ocean advective heat flux is partially compensated by changes in the deep convection, which weakens significantly as the SPG warms (primarily in the Labrador Sea, not shown). Changes in surface fluxes also appear to play an important role in the hindcasts, but the surface flux term is not significant at any lead-time (not shown) and so reflects atmospheric noise.

The lead-time adjustment of ocean advection flux appears to be consistent with the evolution of the AMOC in HiGEM-DP hindcasts. In particular, the initialisation of a weak AMOC and subsequent large increase seen in the early HiGEM-DP hindcasts in the 1960s and 1970s start dates, as described by Shaffrey et al. (2016) (their Fig. 9). Excluding the HiGEM-DP hindcasts starting before 1980 from the calculation of both the lead-time dependent climatology and hindcast-bias substantially reduces the initial drop and subsequent increase in hindcast-bias and ocean advection with lead-time (not shown). However, although the lead-time dependent climatology is different when the 1960–1980 hindcasts are excluded, we still find that the lead-time dependent hindcast-bias and the lead-time dependent climatology (i.e. Fig. 2a) remains comparable (not shown). Thus, we are further satisfied that the lead-time dependent hindcast-bias and the lead-time dependence of the hindcast climatology are due to the same processes. Therefore, using the lead-time dependent climatology removes the lead-time dependent hindcast-bias.

3.2 Case studies of subpolar gyre decadal change

Now that we have examined HiGEM-DP’s overall ability to capture heat content in the SPG we turn our attention to specific case studies of decadal change. In particular, we focus on the specific case studies that have been studied previously, namely the 1960s cooling (Robson et al. 2014b) and the 1990s warming (Robson 2012b). Additionally, we also examine the cooling of the SPG from 2005–2014 Robson et al. (2016).

3.2.1 The 1960s cooling

Figure 3a shows that a cooling is captured in all members of the 1965 start date. The transient runs also cool slightly in the early 1960s, consistent with the eruption of Agung in 1963 (Stocker et al. 2014). However, the cooling of the transient runs is weak compared to the cooling in the initialised hindcasts.

Figure 3d shows that the ensemble-mean SPG (e.g. 60–10\(^{\circ }\)W, 50–65\(^{\circ }\)N) cooling is driven by both advective and surface flux anomalies. Surface fluxes appear to be the largest component in 3-year-mean anomalous fluxes for years 1–3 and 2–4 (see Fig. 3g). However, anomalously weak ocean heat transport convergence also plays an important role and is significantly weaker until the 4–6 year lead-time (see Fig. 3g). The magnitude of the implied heat content change (relative to the transient runs) resulting from anomalous ocean advection and surface fluxes are approximately equal in size after 5 years (compare the lines with the crosses in Fig. 3d). As the SPG cools a small increase in deep convection compensates (Fig. 3d), but the magnitude of the increase is not significant (see Fig. 3g). After \(\sim \)5 years the advective flux becomes anomalously positive, and becomes the dominant term after year \(\sim \)6, driving a subsequent warming of the SPG.

Figure 4a shows that the anomalously low advection in the first 5 years of the 1965 hindcast is associated with anomalously low MHT at the southern boundary of the SPG (i.e. \(\sim \)50\(^{\circ }\)N). The anomalously low MHT between 30–60\(^{\circ }\)N in the first few years is largely due to \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\) (i.e. an anomalously weak circulation) and is associated with the “overturning” component of MHT (not shown), which is similar to a previous study of the UK Met Office Decadal Prediction System (Robson et al. 2014b). However, after year 2, and at the latitudes of the SPG (i.e. 50–65\(^{\circ }\)N), \(\bar{v}T^{\prime }\) and the “gyre” component (not shown) dominates the low MHT.

Shows the same as Fig. 5, but now for the corresponding sections of the transient runs

After year \(\sim \)5 the MHT becomes anomalously strong over the 30–60\(^{\circ }\)N latitudes. The increase in MHT at 50\(^{\circ }\)N is largely associated with an increase in \(\bar{v}T^{\prime }\) at \(\sim \)50\(^{\circ }\)N (Fig. 4c), which itself follows an increase in \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\) at \(\sim \)40\(^{\circ }\)N (Fig. 4b). The increase in \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\) at \(\sim \)40\(^{\circ }\)N is, by visual inspection of time-series, similar to the evolution of the AMOC in this hindcast (i.e. a continued spin up of the AMOC; see Fig. 9 in Shaffrey et al. (2016) for AMOC at 45\(^{\circ }\)N), and is also similar to the change in the “overturning” component of MHT (not shown). Therefore, the warming of the 1965 hindcast after year 6 appears consistent with the non-linear state-dependent drifts in the AMOC.

We now turn our attention to the regional pattern of the cooling. Figure 5 shows that, over the full 10 years of the 1965 hindcast,Footnote 3 surface flux cooling dominates across the whole SPG (Fig. 5b). The cooling due to surface fluxes is strongest in the western SPG and Labrador Sea, but it is partially offset by increased deep convection (see Fig. 5c), which is significant when considering only the western SPG, 60\(^{\circ }\)W–35\(^{\circ }\)W (not shown). Ocean advection contributes to a cooling of the eastern SPG in the first 5 years (not shown), but over 10 years the advection leads to a warming along the Gulf Stream extension and eastern SPG consistent with the spin-up of the AMOC at long-leads.

To compare with the observations we fit a 10 year linear-trend over the same period as the 1965 hindcast (i.e. 1966–1975) in order to focus on the low-frequency changes. Overall the spatial pattern of the cooling in HiGEM-DP is similar to that observed (compare Fig. 5d, e). However, there is less cooling in the East SPG in HiGEM-DP, consistent with the spin-up of the AMOC in this hindcast. In contrast to HiGEM-DP, the transient runs do not capture the observed spatial pattern of the SPG cooling (see Fig. 6d). Instead the transients capture a cooling of the Gulf Stream extension (Fig. 6d), which is largely due to surface flux changes (Fig. 6b).

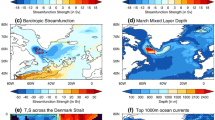

The predicted surface climate fields from hindcasts started between 1990 and 1995. a Shows November–March (NDJFM) SAT and SST predicted by HiGEM-DP hindcasts started every year between 1990 and 1995 averaged over lead-times 1–5 years, relative to lead-time dependent hindcast climatology. b, c Shows the equivalent time period (years 1991–2000) in the transient runs and observations. d, f Shows the same as (a–c) but now for sea level pressure (SLP). Stippling shows where the results are significant at the p \(\le \) 0.1 when compared to all other anomalies, based on a Student’s T test

3.2.2 The 1990s warming

The 1990s warming is captured by all of the ensemble members of the 1995 HiGEM-DP hindcast (see Fig. 3b). HiGEM-DP hindcasts initialised every year from 1990 to 1994 also capture the mid-1990s warming (see Fig. S1). Note that this following section only discusses the 1995 hindcast, but the results are consistent across the other hindcasts from the early 1990s.

The ensemble mean warming of the 1995 hindcast is dominated by an anomalous increase in ocean advective warming (see Fig. 3e), which is largely due to anomalously large ocean advective flux in the first 5 years (see Fig. 3h). The ocean advection accounts for almost all of the total heat content change in the SPG in this hindcast. In contrast, surface fluxes contribute less to the total SPG warming, but do contribute to the inter-annual variability and some warming at long-lead times. The convective flux plays a smaller role in the evolution, but does reduce significantly following the warming of the SPG (see Fig. 3h) as deep convection reduces (not shown).

The increase in ocean advection into the SPG is associated with an anomalously strong MHT into the SPG’s southern boundary (see Fig. 4d). The increase in MHT between 35–45\(^{\circ }\)N (i.e. South of the SPG) is largely due to an increase in \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\), which is also found in the “overturning” component of the heat transport (not shown). Therefore, the mid-1990s warming in HiGEM-DP is consistent with the initialisation of a stronger AMOC at this time [see Fig. 9 in Shaffrey et al. (2016)], consistent with previous studies (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012). However, between 45 and 60\(^{\circ }\)N the anomalously strong MHT is largely associated with \(\bar{v}T^{\prime }\) and the horizontal heat transport (i.e. the “gyre”; not shown).

Although ocean advection dominates the basin-wide SPG warming, a more complicated picture emerges regionally. Ocean advection dominates the eastern SPG (35–10\(^{\circ }\)W), but makes a small contribution to the western SPG (60–35\(^{\circ }\)W, see Fig. 5f). The warming in the East SPG due to advection is damped by the surface fluxes. However, in the west SPG surface fluxes act to warm the ocean (see Fig. 5g) and a reduction in deep convection damps the overall warming (see Fig. reffig:spaspshbudh). The spatial pattern of the resulting change in 0–500 m heat content for the HiGEM-DP 1995 hindcast is shown in Fig. 5i, and compares well with the observed 1996–2005 trend (Fig. 5j). In contrast the transient runs do not capture the observed spatial pattern of the SPG warming trend from 1996-2005 (see Fig. 6), and instead there is a warming of the Gulf Stream extension (Fig. 6i) due to both advection and surface fluxes (Fig. 6f, g).

3.2.3 The post-2005 cooling

The final case study that we examine is the North East Atlantic cooling trend between 2005–2014, which has been linked to a decadal-timescale slowdown in the strength of the ocean circulation in the North Atlantic (Robson et al. 2016). All the ensemble members of the 2005 HiGEM-DP hindcast simulate an overall cooling of the SPG following 2005, showing that the predicted cooling is robust. The HiGEM transient runs also simulate a cooling at this time, but the magnitude is weaker than that seen in HiGEM-DP. Note that, as discussed regarding Fig. 1, the rate of this predicted cooling in HiGEM-DP is sensitive to the choice of bias correction, or climatology. However, qualitatively the results, especially the regional heat budgets, are not sensitive to these choices (not shown). We do find, however, that the climatological balance of heat budget terms is different following 2005 when compared to earlier periods in both HiGEM-DP and the transients. Therefore, using the hindcast-mean climatology results in additional linear-trends in the integrated anomalous heat fluxes, which makes Fig. 5 harder to interpret.

The SPG cooling in the 2005 HiGEM-DP hindcast appears due to reduced ocean advection and a reduction in deep convection (Fig. 3f). However, the reduced convection is not significantly different to the transient runs, and ocean advection is only significantly smaller at long-leads (Fig. 3i). In contrast, the changes in surface fluxes and sea-ice both appear to warm the SPG (see Fig. 3f). However, although the surface fluxes appear to contribute a net warming, the warming due to surface fluxes is actually weaker in HiGEM-DP than in the transient runs (i.e. it is also a net cooling relative to the transient runs; compare line with the cross and diamond in Fig. 3f). Therefore, a complex array of mechanisms appear important for driving the basin-wide SPG 0–500 m temperatures in the 2005 hindcast.

When examining the regional heat budget the dominant drivers of 0–500 m ocean heat content become clearer. Specifically, the reduction of the ocean advection term is largely seen in the East SPG (see Fig. 5k), whereas the surface fluxes are warming the entire SPG (see Fig. 5l). In the West SPG, the warming due to surface fluxes is damped considerably by the cooling associated with a reduction in deep convection (see Fig. 5m). Therefore, the resultant spatial pattern of net cooling is dominated by a cooling of the upper ocean in the East SPG (see Fig. 5n), which compares well with the observed trend over this period (see Fig. 5o). In contrast, the transient runs show much less agreement with the observed trends, but do show a small cooling of the eastern SPG, which is also due to a weak ocean advection (see Fig. 6).

Finally, what caused the reduction in ocean advection into the East SPG in the 2005 hindcast? Figure 4g shows that HiGEM-DP simulates a weakening trend of MHT over the 2005–2014 period across much of the North Atlantic. At most latitudes this is largely a result of a decrease in \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\) (see Fig. 4h), which is seen in both vertical and horizontal components (“overturning” and “gyre”, not shown). At the latitudes of the SPG there is also a role for \(\bar{v}T^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 4i), but the magnitude is smaller than \(\upsilon^{\prime }\bar{T}\). Therefore, the cooling of the East SPG from 2005–2014 in HiGEM-DP is largely a result of a weakening of the Atlantic ocean circulation. Therefore, these results support the conclusions of Robson et al. (2016), that ocean circulation played a significant role in the observed cooling of the eastern SPG since 2005.

3.3 Predictions of sea level pressure and surface temperature

With only 10 hindcasts start dates it is difficult to identify robust skill in HiGEM-DP for variable surface climate variables. For example, Shaffrey et al. (2016) showed some limited skill for surface air temperature (SAT) over land for the HiGEM CMIP5 set, but there is no improvement in sea level pressure (SLP, not shown). However, substantial changes in the observed surface climate have been associated with large decadal change events in the North Atlantic ocean (Sutton and Dong 2012; Hodson et al. 2014). Moreover, previous decadal predictions appear to capture significant shifts in surface climate associated with the 1960s cooling and 1990s warming case-studies described above when many hindcasts are averaged together to increase the signal-to-noise (Robson et al. 2013, 2014b; Msadek et al. 2014; Müller et al. 2014). Therefore, we now explore the predicted SLP and surface temperature (SST and SAT) in HiGEM-DP. As the largest number of HiGEM-DP hindcasts and transient runs are available for the early-1990s, we combine the hindcasts initialised every year through 1990–1995 together as in Robson et al. 2014b. Note that no trends were removed from the data before averaging in Fig. 7. The sensitivity to detrending and the patterns simulated by HiGEM-DP for surface temperature in the 1960s and 2000s is shown in supplementary Fig. S2.

Figure 7 shows the comparison of extended-winter (November to March; NDJFM) from years 1–5 for HiGEM-DP hindcasts initialised between 1990–1995. Also shown is the mean of the transient runs and the observations for the verification period (1991-2000, the time period that validates years 1–5 from the 1990–1995 hindcasts). In the North Atlantic HiGEM-DP captures the observed pattern of SST—a cold SPG with anomalously warm SSTs in the Gulf Stream extension (compare Fig. 7a, c). HiGEM-DP also captures anomalously warm temperatures across the Eurasian and North American continents, similar to those seen in observations (although the observed anomalies are not significant). In contrast, the transients do not capture the observed SST pattern in the North Atlantic, and west and northern Eurasia is anomalously cool (see Fig. 7b). Figure 7 also shows that HiGEM-DP also predicts a positive North Atlantic Oscillation in the 1990s [NAO, Hurrell (1995)], which also compares well with observations (Fig. 7f). In contrast, the transient runs tend to capture a weak negative NAO (Fig. 1e). The predicted positive NAO in HiGEM-DP is still present at lags 2–6 and, to a lesser extent, in years 3–7 (not shown), i.e. the NAO signal is not only in the first winter.

Interestingly, the extended winter SST and SLP patterns predicted in Fig. 7 are similar to the patterns that lead a peak in AMOC in the HiGEM control [not shown, but see Hodson and Sutton (2012) for annual means]. As a strong AMOC is initialised in HiGEM-DP in the 1990s (see Shaffrey et al. (2016), their Fig. 9), these results suggest that the ocean plays an important role in maintaining the positive NAO. One way this could occur is through the increased meridional SST gradient increasing baroclinicity (Brayshaw et al. 2011). However, we also find large heat loss in the Gulf Stream extension and eastern SPG in these hindcasts (not shown, but see Fig. 5 for the annual mean heat loss in the 1995 HiGEM-DP hindcast). These are regions that are warmed by increased ocean advection in the hindcasts, and are areas that are thought to influence the atmosphere through changes in surface fluxes (Rodwell et al. 1999); Sato et al. (2014); Peings and Magnusdottir (2015). There is also anomalously strong surface heat loss in the Greenland Sea region in winter in HiGEM-DP, which is also driven by ocean advection (not shown). However, the wintertime response of the atmosphere to Arctic changes is thought to project weakly on the negative NAO (Deser et al. 2010; Petrie et al. 2015). Finally, SST in the tropical Pacific is also thought to influence the atmospheric circulation in the North Atlantic (Brönnimann et al. 2007), but this would not appear to be dominant in HiGEM-DP as the predicted and observed SST in the tropical east Pacific are the opposite sign to those observed.

In the extended summer (May–September; MJJAS) HiGEM-DP also captures the observed warm SST pattern in the North Atlantic, but does not capture the observed SLP anomalies (not shown). SST anomalies in the tropical east Pacific also influence atmospheric circulation in the North Atlantic region in the summer (Brönnimann et al. 2007; Folland et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2010). Thus, it may be that the erroneous prediction of cool anomalies in the tropical Pacific is an important influence of Atlantic atmospheric circulation in summer in HiGEM-DP.

4 Discussion

The results presented here are generally in agreement with the analysis of other prediction systems (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012; Msadek et al. 2014; Robson et al. 2014b; Hermanson et al. 2014), which further suggests the high predictability seen in the SPG region across multiple systems (Doblas-Reyes et al. 2013; Kirtman et al. 2013; García-Serrano et al. 2015) is robust. However, there are some details that warrant some brief discussion, including the relative importance of different mechanisms, the prediction of atmospheric anomalies, the presence of hindcast drift and the importance of model resolution.

HiGEM-DP appears to capture the evolution of the North Atlantic SPG with considerable skill, particularly for specific large events studied before, (e.g. in the 1960s and 1990s), but also for a more recent cooling of the Eastern SPG since 2005. The initialisation of ocean heat transport plays an important role in successfully predicting the SPG on decadal time-scales in HiGEM-DP in all the events. However, it is important to point out that some results are somewhat different to previous studies. For example, surface heat fluxes were found to be relatively more important in the 1960s cooling in HiGEM-DP compared to the UK Met Office’s Decadal Prediction System based on HadCM3 (Robson et al. 2014b). The advection of temperature anomalies by the mean circulation at the latitudes of the SPG (50\(^{\circ }\)N), as opposed to changes in the circulation strength, also appears to be more important in HiGEM compared to HadCM3 based hindcasts, particularly in the 1990s (Robson et al. 2012b, 2014b). Thus, the relative importance of ocean circulation for producing successful decadal predictions of the North Atlantic SPG, rather than the mean-circulation simply propagating the initialised heat content anomalies in to that region, is still not fully resolved.

The results suggesting that HiGEM-DP is able to capture the anomalous winter-time atmospheric circulation in the 1990s is also encouraging for the prospect of developing useful multi-annual climate predictions for the North Atlantic region. Although the results presented here supports a role of the ocean in driving the observed atmospheric circulation, it is worth reiterating that we find no mean skill in predicting the SLP in the North Atlantic in HiGEM. However, there is an emerging literature suggesting a large number of start-dates and ensemble members are needed for the predictable signal to emerge from the noise in current models (Scaife et al. 2014; Eade et al. 2014; Dunstone et al. 2016). The early 1990s period is the best sampled by HiGEM-DP, and so these results provide tentative evidence that the winter-time atmospheric circulation in the Atlantic sector is predictable on multi-annual timescales in HiGEM-DP, supporting recent advances in seasonal (Scaife et al. 2014; Stockdale et al. 2015) and inter-annual prediction (Dunstone et al. 2016). Ultimately, further analysis and experiments, which are beyond the scope of this study, will be needed to understand the robustness of this predictability in HiGEM-DP, and the mechanisms responsible.

The analysis has highlighted that HiGEM-DP has a lead-time dependent hindcast-bias in the 0–500 m temperature in the SPG, which is related to a non-linear state-dependent drift in the AMOC, as shown in Shaffrey et al. (2016). The AMOC adjustments clearly impact on the predictions of the SPG in the 1960s and 1970s. However, the start-date dependence of the adjustment, coupled with few hindcast start-dates, makes it difficult to untangle the impact of drift on all start-dates. Furthermore, it is also not clear what the origin of the AMOC drift is. The drift could be related to an incorrect forced response, or, due to problems with the initialisation procedure (Shaffrey et al. 2016). Therefore, understanding the origin of these drifts, and their impact on the predictions, through further detailed analysis and sensitivity experiments [i.e. Sanchez-Gomez et al. (2015)] is required in order to minimise them.

Although HiGEM has substantial skill at capturing the observed changes in SPG 0–500 m heat content, we do not argue that the skill is due to the resolution of the model. Indeed, for the limited number of start dates presented here, there is no significant difference between ACC for HiGEM and the low-resolution HadCM3 model (Smith 2013) for SPG 0–500 m heat content (not shown). Rather, here we have used HiGEM-DP to test the robustness of the mechanisms that lead to skill in decadal predictions of the North Atlantic. Although we can not say anything definitively in terms of the impact of resolution on prediction skill, evidence does support an important role for model resolution (atmosphere and ocean) in terms of capturing response of the atmosphere to oceanic anomalies (Minobe et al. 2008; Bryan et al. 2010; Siqueira and Kirtman 2016). In that regard, improved resolution may have had an impact on the atmospheric response in the early-1990s in HiGEM-DP hindcasts (i.e. Fig. 7), but further analysis and experiments will be needed to understand the impact of model resolution on decadal predictions.

5 Conclusions

In this paper we have analysed initialised decadal predictions of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre (SPG) made with the high-resolution HiGEM Decadal Prediction system (HiGEM-DP). The key results are as follows:

-

HiGEM-DP has substantial skill at predicting the evolution of the SPG heat content. Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) skill is above 0.65 for all 10 years of the hindcasts, comfortably outperforming persistence at lead-times greater than 5 years. HiGEM-DP also significantly out-performs the HiGEM transient runs at most lead-times. Therefore, initialisation with observations clearly benefits predictions in the North Atlantic SPG, consistent with previous studies (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012; Msadek et al. 2014; Robson et al. 2014b; Hermanson et al. 2014).

-

HiGEM-DP is able to capture the large-scale shifts in the SPG heat content, including the spatial pattern of decadal change, in the 1960s and in the 1990s, and also a cooling of the eastern SPG since 2005. Ocean advection is generally the dominant term for the whole SPG, consistent with previous studies (Robson 2012b; Yeager et al. 2012; Msadek et al. 2014; Robson et al. 2014b). However, when examining the regional heat budgets we find different mechanisms control the heat budget of the East (ocean advection) and West (surface fluxes) SPG.

-

In the 1960s surface flux cooling and a reduction in ocean heat transport dominate the SPG cooling in HiGEM-DP. The reduction in ocean heat transport convergence is consistent with an initially weak ocean circulation. However, a strong, and erroneous, strengthening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation [AMOC; (see Shaffrey et al. (2016))], causes the hindcasts to warm at long lead-times.

-

In the 1990s anomalously strong ocean heat transport convergence dominates the SPG warming. At latitudes south of the SPG (e.g. 40–50\(^{\circ }\)N) the initialisation of a stronger ocean circulation dominates ocean heat transports. However, at the latitudes of the SPG, the advection of anomalous temperature anomalies by the mean circulation is dominant.

-

The cooling of the SPG after 2005 is dominated by a reduction in ocean heat transport convergence, particularly in the eastern SPG. The reduced ocean heat transport is largely due to a weakening ocean circulation. Thus, the cooling in HiGEM-DP is consistent with the analysis of Robson et al. (2016).

-

Hindcasts in the early 1990s predict a significant shift towards positive NAO like conditions and are, generally, consistent with the observed NAO anomalies in the 1990s. This result suggests that the ocean’s state may provide some predictability of the NAO at multi-annual time-scales.

The analysis of SPG heat content prediction in HiGEM-DP—which has a higher resolution than the majority of models used for decadal prediction thus far (Kirtman et al. 2013)—builds confidence that North Atlantic ocean heat content can be predicted years in advance. By focusing on three independent case-studies of North Atlantic decadal change events the analysis presented here gives further support to the important role of ocean heat transport and ocean circulation in driving the observed changes in North Atlantic ocean heat content in the recent past (Robson et al. 2012a, 2014b; Yeager et al. 2012; Hermanson et al. 2014). Therefore, these results are encouraging for the prospects of making useful predictions of the North Atlantic. Nevertheless, as outlined in the discussion, further understanding is needed to quantify the robustness of the different mechanisms, to minimise hindcast drift, and to understand the role of model resolution in delivering improved predictions. Therefore, we suggest that process-based assessment of hindcasts for well observed case-studies in a range of prediction systems, alongside carefully designed sensitivity tests, will remain a valuable exercise for developing decadal prediction systems for the foreseeable future.

Notes

Note that the only exception to the use of this lead-dependent climatology is for 0–500 average temperature anomalies presented in Fig. 1a, which uses a time-invariant climatology calculated from the assimilation run, and the SER in Fig. 1d, where the lead-time dependent mean-bias has been corrected.

Note that the Sea-Ice term is usually small and highly localised. However, we include the term in the analysis for completeness.

Note, the spatial pattern for the 1965 hindcast is especially sensitive to the number of years used to calculate the trends due to the strong SPG warming after year 5. However, for consistency with the other case-studies we present the 10-year trends.

References

Allan R, Ansell T (2006) A new globally complete monthly historical gridded mean sea level pressure dataset (HadSLP2): 18502004. J Clim 19(22):5816–5842. doi:10.1175/JCLI3937.1

Brayshaw DJ, Hoskins B, Blackburn M (2011) The basic ingredients of the North Atlantic storm track. Part II: sea surface temperatures. J Atmos Sci 68(8):1784–1805. doi:10.1175/2011JAS3674.1

Brönnimann S, Xoplaki E, Casty C, Pauling A, Luterbacher J (2007) ENSO influence on Europe during the last centuries. Clim Dyn 28(2–3):181–197. doi:10.1007/s00382-006-0175-z

Bryan FO, Tomas R, Dennis JM, Chelton DB, Loeb NG, McClean JL (2010) Frontal scale air-sea interaction in high-resolution coupled climate models. J Clim 23(23):6277–6291. doi:10.1175/2010JCLI3665.1

Bryan K (1969) Climate and the ocean circulation. Mon Weather Rev 97(11):806–827

Corti S, Weisheimer A, Palmer T, Doblas-Reyes F, Magnusson L (2012) Reliability of decadal predictions. Geophys Res Lett 39:L21712. doi:10.1029/2012GL053354

Cox MD (1984) A primitive equation, 3-dimensional model of the ocean. GFDL ocean group technical report 1

Deser C, Tomas R, Alexander M, Lawrence D (2010) The seasonal atmospheric response to projected arctic sea ice loss in the late twenty-first century. J Clim 23(2):333–351. doi:10.1175/2009JCLI3053.1

Doblas-Reyes F, Andreu-Burillo I, Chikamoto Y, García-Serrano J, Guemas V, Kimoto M, Mochizuki T, Rodrigues L, Van Oldenborgh G (2013) Initialized near-term regional climate change prediction. Nat Commun 4:1715. doi:10.1038/ncomms2704

Dong B, Sutton R (2002) Variability in North Atlantic heat content and heat transport in a coupled ocean-atmosphere GCM. Clim Dyn 19(5):485–497. doi:10.1007/s00382-002-0239-7

Dunstone N, Smith D, Scaife A, Hermanson L, Eade R, Robinson N, Andrews M, Knight J (2016) Skilful predictions of the winter North Atlantic oscillation one year ahead. Nat Geosci 9:809–814. doi:10.1038/ngeo2824

Eade R, Smith D, Scaife A, Wallace E, Dunstone N, Hermanson L, Robinson N (2014) Do seasonal-to-decadal climate predictions underestimate the predictability of the real world? Geophys Res Lett 41:5620–5628. doi:10.1002/2014GL061146

Folland CK, Knight J, Linderholm HW, Fereday D, Ineson S, Hurrell JW (2009) The summer North Atlantic oscillation: past, present, and future. J Clim 22:1082–1103. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2459

García-Serrano J, Doblas-Reyes FJ, Coelho CA (2012) Understanding Atlantic multi-decadal variability prediction skill. Geophys Res Lett 39(L18):708. doi:10.1029/2012GL053283

García-Serrano J, Guemas V, Doblas-Reyes FJ (2015) Added-value from initialization in predictions of atlantic multi-decadal variability. Clim Dyn 44:2539–2555. doi:10.1007/s00382-014-2370-7

Getzlaff J, Böning CW, Eden C, Biastoch A (2005) Signal propagation related to the North Atlantic overturning. Geophys Res Lett 32(L09):602. doi:10.1029/2004GL021002

Goldenberg S, Landsea C, Mestas-Nuñez A, Gray W (2001) The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity: causes and implications. Science 293:474–479. doi:10.1126/science.1060040

Good SA, Martin MJ, Rayner NA (2013) EN4: quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J Geophys Res Oceans 118:6704–6716. doi:10.1002/2013JC009067

Gordon C, Cooper C, Senior C, Banks H, Gregory J, Johns T, Mitchell J, Wood R (2000) The simulation of SST, sea ice extents and ocean heat transports in a version of the Hadley Centre coupled model without flux adjustments. Clim Dyn 16:147–168. doi:10.1007/s003820050010

Hermanson L, Eade R, Robinson NH, Dunstone NJ, Andrews MB, Knight JR, Scaife AA, Smith DM (2014) Forecast cooling of the Atlantic subpolar gyre and associated impacts. Geophys Res Lett 41:5167–5174. doi:10.1002/2014GL060420

Ho CK, Hawkins E, Shaffrey L, Bröcker J, Hermanson L, Murphy JM, Smith DM, Eade R (2013) Examining reliability of seasonal to decadal sea surface temperature forecasts: the role of ensemble dispersion. Geophys Res Lett 40(21):5770–5775

Hodson DL, Sutton RT (2012) The impact of resolution on the adjustment and decadal variability of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in a coupled climate model. Clim Dyn 39(12):3057–3073. doi:10.1007/s00382-012-1309-0

Hodson DL, Robson JI, Sutton RT (2014) An anatomy of the cooling of the North Atlantic ocean in the 1960s and 1970s. J Clim 27:8229–8243. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00301.1

Hurrell JW (1995) Decadal trends in the North Atlantic oscillation: regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269:676–679. doi:10.1126/science.269.5224.676

Johns TC, Durman CF, Banks HT, Roberts MJ, McLaren AJ, Ridley JK, Senior CA, Williams K, Jones A, Rickard G et al (2006) The new Hadley Centre climate model (HadGEM1): evaluation of coupled simulations. J Clim 19(7):1327–1353

Kirtman B, Power S, Adedoyin J, Boer G, Bojariu R, Camilloni I, Doblas-Reyes F, Fiore A, Kimoto M, Meehl G, Prather M, Sarr A, Schär C, Sutton R, van Oldenborgh G, Vecchi G, Wang H (2013) Near-term climate change: projections and predictability. In: Stocker TF et al (eds) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kloewer M, Latif M, Ding H, Greatbatch RJ, Park W (2014) Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and the prediction of North Atlantic sea surface temperature. Earth Planet Sci Lett 406:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.09.001

Knight JR, Folland CK, Scaife AA (2006) Climate impacts of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Geophys Res Lett 33:L17706. doi:10.1029/2006GL026242

Kuhlbrodt T, Gregory J, Shaffrey L (2015) A process-based analysis of ocean heat uptake in an AOGCM with an eddy-permitting ocean component. Clim Dyn 45:3205–3226. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2534-0

Marzocchi A, Hirschi JJM, Holliday NP, Cunningham SA, Blaker AT, Coward AC (2015) The North Atlantic subpolar circulation in an eddy-resolving global ocean model. J Marine Syst 142:126–143. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2014.10.007

Matei D, Pohlmann H, Jungclaus J, Müller W, Haak H, Marotzke J (2012) Two tales of initializing decadal climate prediction experiments with the ECHAM5/MPI-OM model. J Clim 25:8502–8523. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00633.1

McCarthy GD, Haigh ID, Hirschi JJM, Grist JP, Smeed DA (2015) Ocean impact on decadal Atlantic climate variability revealed by sea-level observations. Nature 521:508–510. doi:10.1038/nature14491

McLaren A, Banks H, Durman C, Gregory J, Johns T, Keen A, Ridley J, Roberts M, Lipscomb W, Connolley W et al (2006) Evaluation of the sea ice simulation in a new coupled atmosphere-ocean climate model (HadGEM1). J Geophys Res Oceans 111(C12). doi:10.1029/2005JC003033

Minobe S, Kuwano-Yoshida A, Komori N, Xie SP, Small RJ (2008) Influence of the gulf stream on the troposphere. Nature 452:206–209. doi:10.1038/nature06690

Monerie PA, Coquart L, Maisonnave É, Moine MP, Terray L, Valcke S (2017) Decadal prediction skill using a high-resolution climate model. Clim Dyn 1–24. doi:10.1007/s00382-017-3528-x

Morice CP, Kennedy JJ, Rayner NA, Jones PD (2012) Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: the HadCRUT4 data set. J Geophys Res Atmos 117(D8). doi:10.1029/2011JD017187

Msadek R, Delworth T, Rosati A, Anderson W, Vecchi G, Chang YS, Dixon K, Gudgel R, Stern W, Wittenberg A et al (2014) Predicting a decadal shift in North Atlantic climate variability using the GFDL forecast system. J Clim 27:6472–6496. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00476.1

Müller WA, Pohlmann H, Sienz F, Smith D (2014) Decadal climate predictions for the period 1901–2010 with a coupled climate model. Geophys Res Lett 41:2100–2107

Peings Y, Magnusdottir G (2015) Wintertime atmospheric response to Atlantic multidecadal variability: effect of stratospheric representation and ocean–atmosphere coupling. Clim Dyn 1–19. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2887-4

Petrie RE, Shaffrey LC, Sutton RT (2015) Atmospheric impact of Arctic Sea ice loss in a coupled ocean-atmosphere simulation*. J Clim 28:9606–9622. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0316.1

Rayner N, Parker D, Horton E, Folland C, Alexander L, Rowell D, Kent E, Kaplan A (2003) Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J Geophys Res Atmos 108(D14):4407

Robson J, Sutton R, Lohmann K, Smith D, Palmer M (2012a) Causes of the rapid warming of the North Atlantic ocean in the mid 1990s. J Clim 25:4116–4134. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00443.1

Robson J, Sutton R, Smith D (2013) Predictable climate impacts of the decadal changes in the ocean in the 1990s. J Clim 26:6329–6339. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00827.1

Robson J, Hodson D, Hawkins E, Sutton R (2014a) Atlantic overturning in decline? Nat Geosci 7:2–3. doi:10.1038/ngeo2050

Robson J, Sutton R, Smith D (2014b) Decadal predictions of the cooling and freshening of the north atlantic in the 1960s and the role of ocean circulation. Clim Dyn 42:2353–2365. doi:10.1007/s00382-014-2115-7

Robson J, Ortega P, Sutton R (2016) A recent reversal of climatic trends in the north atlantic. Nat Geosci 9:513–517. doi:10.1038/ngeo2727

Robson JI, Sutton RT, Smith DM (2012b) Initialized predictions of the rapid warming of the North Atlantic ocean in the mid 1990s. Geophys Res Lett 25(L19):713. doi:10.1029/2012GL053370

Rodwell MJ, Rowell DP, Folland CK (1999) Oceanic forcing of the wintertime North Atlantic Oscillation and European climate. Nature 398(6725):320–323

Sanchez-Gomez E, Cassou C, Ruprich-Robert Y, Fernandez E, Terray L (2015) Drift dynamics in a coupled model initialized for decadal forecasts. Clim Dyn 46:1819–1840. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2678-y

Sato K, Inoue J, Watanabe M (2014) Influence of the Gulf Stream on the Barents Sea ice retreat and Eurasian coldness during early winter. Environ Res Lett 9(084):009

Scaife A, Arribas A, Blockley E, Brookshaw A, Clark R, Dunstone N, Eade R, Fereday D, Folland C, Gordon M et al (2014) Skillful long-range prediction of European and North American winters. Geophys Res Lett 41:2514–2519. doi:10.1002/2014GL059637

Shaffrey LC, Stevens I, Norton WA, Roberts MJ, Vidale PL, Harle JD, Jrrar A, Stevens DP, Woodage MJ, Demory ME et al (2009) UK HiGEM: the new UK high-resolution global environment model-model description and basic evaluation. J Clim 22:1861–1896. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2508.1

Shaffrey LC, Hodson D, Robson J, Stevens DP, Hawkins E, Polo I, Stevens I, Sutton RT, Lister G, Iwi A, Smith D, Stephens A (2016) Decadal predictions with the HiGEM high resolution global coupled climate model: description and basic evaluation. Clim Dyn. doi:10.1007/s00382-016-3075-x

Siqueira L, Kirtman BP (2016) Atlantic near-term climate variability and the role of a resolved gulf stream. Geophys Res Lett 43:3964–3972. doi:10.1002/2016GL068694

Smeed D, McCarthy G, Cunningham S, Frajka-Williams E, Rayner D, Johns W, Meinen C, Baringer M, Moat B, Duchez A et al (2013) Observed decline of the Atlantic Meridional overturning circulation 2004 to 2012. Ocean Sci Discuss 10:1619–1645. doi:10.5194/os-10-29-2014

Smith DM, Murphy JM (2007) An objective ocean temperature and salinity analysis using covariances from a global climate model. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2005JC003172

Smith DM, Cusack S, Colman AW, Folland CK, Harris GR, Murphy JM (2007) Improved surface temperature prediction for the coming decade from a global climate model. Science 317:796–799. doi:10.1126/science.1139540

Smith DM, Eade R, Dunstone NJ, Fereday D, Murphy JM, Pohlmann H, Scaife AA (2010) Skilful multi-year predictions of Atlantic hurricane frequency. Nat Geosci 3:846–849. doi:10.1038/ngeo10

Smith DM, Eade R, Pohlmann H (2013) A comparison of full-field and anomaly initialization for seasonal to decadal climate prediction. Clim Dyn 41:3325–3338. doi:10.1007/s00382-013-1683-2

Smith DM, Allan RP, Coward AC, Eade R, Hyder P, Liu C, Loeb NG, Palmer MD, Roberts CD, Scaife AA (2015) Earth’s energy imbalance since 1960 in observations and CMIP5 models. Geophys Res Lett 42:1205–1213. doi:10.1002/2014GL062669

Stockdale TN, Molteni F, Ferranti L (2015) Atmospheric initial conditions and the predictability of the Arctic oscillation. Geophys Res Lett 42:1173–1179. doi:10.1002/2014GL062681

Stocker T, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (2014) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sutton RT, Dong B (2012) Atlantic ocean influence on a shift in European climate in the 1990s. Nat Geosci 5(11):788–792. doi:10.1038/NGEO1595

Sutton RT, Hodson DLR (2005) Atlantic ocean forcing of North American and European summer climate. Science 309:115–117. doi:10.1126/science.1109496

Volkov DL, Lee T, Fu LL (2008) Eddy-induced meridional heat transport in the ocean. Geophys Res Lett 35(L20):601. doi:10.1029/2008GL035490

Yeager S, Karspeck A, Danabasoglu G, Tribbia J, Teng H (2012) A decadal prediction case study: late twentieth-century North Atlantic ocean heat content. J Clim 25:5173–5189. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00595.1

Yeager SG, Karspeck AR, Danabasoglu G (2015) Predicted slowdown in the rate of Atlantic sea ice loss. Geophys Res Lett 42(24):10,704–10,713. doi:10.1002/2015GL065364

Zhang R, Delworth T (2006) Impact of Atlantic multidecadal oscillations on India/Sahel rainfall and Atlantic hurricanes. Geophys Res Lett. doi:10.1029/2006GL026267

Acknowledgements

We thank Rowan Sutton and Ed Hawkins for useful discussions. J.R. was supported by the ‘Seasonal-to-Decadal Climate Prediction for the Improvement of European Climate Services’ project (SPECS, GA 308378) the ‘Dynamics and Predictability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning and Climate’ project (DYNAMOC, NE/M005127/1) and the ‘North Atlantic Climate System Integrated Study’ (ACSIS) project. I.P. was supported by BNP-Paribas foundation via the PRECLIDE project under the CNRS research convention agreement No. 30023488. L.C. was funded by the NERC IMPETUS project (NE/L010488/1), and L.C. and D.H. funded by NERC via NCAS. This work made use of the high-performance computing facilities of HECToR, which was provided by the University of Edinburgh. We thank the anonymous reviewer for their useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Robson, J., Polo, I., Hodson, D.L.R. et al. Decadal prediction of the North Atlantic subpolar gyre in the HiGEM high-resolution climate model. Clim Dyn 50, 921–937 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3649-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3649-2