Abstract

Wind climate in Northwest Europe is subject to long-term persistence (LTP), also called the Hurst phenomenon. Ignorance of LTP causes underestimation of climatic variability. The quantification of multi-year variability is important for the assessment of the uncertainty of future multi-year wind yields. Estimating LTP requires long homogeneous time series. Such series of wind observations are rare, but annual mean geostrophic wind speed (U) can be used instead. This study demonstrates a method to estimate the 10-year aggregated mean U for the near and the far future and its uncertainty in Northwest Europe. Time series of U were derived from daily sea level pressure from the European Climate Assessment Dataset. Minor inhomogeneities cannot be ruled out, but were shown to hardly affect the estimated Hurst exponent \((\hat{H})\). A maximum likelihood method was adjusted to remove the biases in \(\hat{H}\). The geostrophic wind speed over the North Sea, the British Isles and along the Scandinavian coast are characterised by statistically significant H between 0.58 and 0.74, (H = 0.5 implies no LTP). The additional affect of the parameter uncertainty is estimated in a Bayesian way and is highly dependent on the record length. The assessment of structural changes in future wind fields requires general circulation models. An ensemble of seventeen simulations (ESSENCE) with one single climate model (ECHAM5/MPI-OM) was used to evaluate structural trends and LTP. The estimated \(\hat{H}\) in the ESSENCE simulations are generally close to 0.5 and not significant. Significant trends in U are found over large parts of the investigated domain, but the trends are small compared to the multi-year variability. Large decreasing trends are found in the vicinity of Iceland and increasing trends near the Greenland coast. This is likely related to the sea ice retreat within the ESSENCE simulations and the associated change in surface temperature gradients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Financiers of new wind farms are typically interested in the expected aggregated mean wind energy yield for a future operating period—usually 10–20 years—in combination with some measure of uncertainty (Albers 2004). Estimations of aggregated wind energy yields over a period of k years (Y (k)) are usually based on past wind climate time series. Vautard et al. (2010) found a downward trend in observed surface winds for most of the northern Hemisphere between 1979 and 2008. They hypothesised that this stilling is partly due to increasing surface roughness caused by increasing vegetation. For The Netherlands, this was confirmed by Wever (2011) who attributed 40% of the observed decrease (1981–2009) in 10m wind to changed local surface roughness, 30% to changed mesoscale roughness and 30% to variations in large-scale circulation. At the hub height of modern wind turbines (60–100 m) the effect of local surface roughness is limited; mesoscale roughness does still substantially affect the wind supply. Yet, for typical return on investment periods, natural variability may be dominant (Bakker et al. 2011) and changes in surface roughness play, if any, a minor role for offshore wind farms.

In Northwest Europe, the wind climate is subject to considerable long-term variability. A distinct increase has been reported from the 1960s until the mid 1990s (Pryor and Barthelmie 2003; Alexander et al. 2005). The high average wind and storm conditions in the mid nineties, however, are not so extraordinary when compared to the 1880s (e.g. Alexandersson et al. 1998, 2000; Matulla et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2009). Therefore, Kaas et al. (1996) and WASA (1998) concluded that the wind climate of northern Europe has not structurally changed in the last 100–150 years. The large multi-year fluctuations are generally ascribed to natural climate variability.

Wind and other geophysical processes often show such long-term variations (Hurst 1951). One manifestation of the “Hurst phenomenon”, or long-term persistence (LTP), is the tendency of similar extreme events to cluster close together in time, like droughts in hydrology or extreme storms in wind climate. This behaviour is referred to with several other names, like simple scaling stochastic process (SSS) (Koutsoyiannis 2006) and Hurst-Kolmogorov behaviour (Tyralis and Koutsoyiannis 2011).

In practice, fluctuations that persist for many years, are often dealt with by breaking the series up into a sequence of deterministic trends. Koutsoyiannis (2006) addressed that many hydrologists use the complete time series after detrending, i.e. subtracting some linear or non-linear trend. Sometimes, an extrapolation of the trend is used for the future prediction. In the wind industry, uncertainty estimates of Y (k) are often based on a recent “stationary” episode (e.g. Segers 2009; Knight and Harrison 2006). Both methods neglect the possibility of changes in the trend within the time range of the prediction, although such trend changes have been observed in the past. This approach may be justified if those changes are well understood; the decrease in windiness in Northwest Europe from the last decades is, for instance, partly attributed to increased surface roughness (Vautard et al. 2010; Wever 2011). On the other hand, natural variations of the atmospheric circulation were just as important or even more important and future evolution of this chaotic component of the atmospheric circulation is highly unpredictable (Bakker et al. 2011). Therefore, it is preferred to recognise the unpredictability and accept the trends as a result of stationary, natural long-term variability.

The Hurst phenomenon can be quantified through the Hurst exponent (H), which varies from 0.5 in the absence of LTP (e.g. white noise) up to 1.0 (Koutsoyiannis 2003). Let μ Y be the population mean and σ Y the population standard deviation of Y (1) then the expected value of the k-year aggregated yield mean is not dependent on H:

However, the standard deviation of Y (k) is greatly affected by H:

which for H = 0.5 reduces to the classical statistics law

To illustrate this for fixed μ Y and σ Y ; StD(Y (10)) is 1.26 times larger if H = 0.6 and 2.00 times larger if H = 0.8 compared to a process without LTP (i.e. H = 0.5).

Estimation of H (and thus estimation of long-term variability) requires long homogeneous time series, i.e. not affected by changes in measurement or local circumstances which influence the measurement. Even for time series of more than 100 observations, estimation of H remains highly uncertain (Koutsoyiannis and Cohn 2008). The high sensitivity of wind speed observations to the local environment and instrumentation implies that long homogeneous wind speed records are very rare. Therefore, long-term trends and variations in wind climate are often investigated by using proxies derived from observed pressure data, such as geostrophic wind speed (e.g. Alexandersson et al. 1998) and pressure tendency (e.g. Alexander et al. 2005; Schmith et al. 1998). If wind conditions averaged over multiple days are required, geostrophic wind speed is preferred. Monthly and annual geostrophic wind speed correlate very well to actual monthly and annual wind energy yields for large parts of northern Europe (Bakker and Bessembinder 2009; Albers 2004).

With respect to future energy resource management it is of interest whether and how northwestern Europe wind climate might change in response to increased greenhouse gases (GHG). General circulation models (GCMs) can be used to explore this response of wind climate to changes in the large scale forcings (Woth et al. 2006; Rockel and Woth 2007). Depending on the wind application, different dynamical or statistical downscaling techniques have been used (Pryor et al. 2005, 2006; Najac et al. 2009). Projected changes in European wind climate differ greatly and many authors note that the results are very uncertain due to the poor representation of the present-day climate conditions by many GCMs and regional climate models (RCMs) (WASA 1998; Pryor et al. 2006; Najac et al. 2009).

Possibly, the wide range in wind climate projections is a manifestation of LTP. Neglecting LTP can cause an erroneous detection of a significant response (Von Storch and Navarra 1995) to increased GHG. For the correct assessment of climate change the existence of LTP should be recognised. Yet, studies on the representation of LTP in GCMs are rare. We are not familiar with studies on the representation of LTP in modelled wind projections. For other variables such as temperature and precipitation LTP is generally underestimated or even absent in GCMs (Rutten 2008; Koutsoyiannis et al. 2008; Vyushin et al. 2002). This may originate from the fact that typical GCM climate runs lack natural variations in their forcings such as GHG concentrations, the solar constant or volcanic eruptions (Vyushin et al. 2004; Rybski et al. 2008).

For typical GCM simulation lengths (100–200 years), it is hard to efficiently detect significant LTP or significant stuctural changes in average wind conditions that are relatively small compared to the multi-year variability. An ensemble of simulations with a single GCM and similar evolution of the boundary conditions (e.g. emission scenario) increases the sample size and is of help in this case. The ESSENCE (Ensemble SimulationS of Extreme weather events under Nonlinear Climate changE) project (Sterl et al. 2008) provides such an ensemble of simulations with a single GCM and a given emission scenario. Differences between the members represent the internal variability at a range of time scales in the GCM.

The main objective of this study is to develop a method to estimate the 10-year mean geostrophic wind speed for the near (coming 10 years) and the far future (around 2050) and its uncertainty due to climate variability. Since LTP strongly affects the uncertainty, the annual geostrophic wind speed in Northwest Europe, derived from pressure observations, is tested for the presence of LTP. Emphasis is put on how to minimize the influence of the unavoidable inhomogeneities in the measurement series. Next, an ensemble (ESSENCE) of seventeen simulations of one global circulation model (GCM) and using one emission scenario is tested for the reproduction of LTP and for a human induced climate response in the geostrophic wind speed. Finally, the multi-year uncertainty derived from the observations is compared to the uncertainty and trends as derived from the ESSENCE ensemble.

2 Data

2.1 ECA&D dataset: sea level pressure

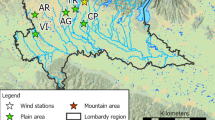

Daily geostrophic wind speed was derived from sea level pressure (slp) gradients between three measurement sites using the triangle method described by Alexandersson et al. (1998). Subsequently, the daily geostrophic wind speed was averaged to annual values (U ECA ). For comparison reasons, triangles were chosen very similar to the triangles analysed by Alexandersson et al. (1998, 2000) and Wang et al. (2009) (Fig. 1; Table 2).

For this purpose, 12 long time series of daily slp in Northwest Europe (Table 1) were obtained from the European Climate Assessment & Dataset (ECA&D) (http://eca.knmi.nl; Klok and Klein Tank 2008). Since the Valentia slp time series has a large gap (1893–1939), triangles have been based on Armagh instead. We used “non-blended” time series as supplied by the participants, which have been completed nor extended with data from nearby stations by the ECA&D-team. This does not automatically mean that all data in one single time series originate from the same source. For example, the unblended slp series of station De Bilt originates partly from Utrecht (1849–1896) and partly from De Bilt (1897–2010). For other time series such information generally lacks.

European Climate Assessment & Dataset provides quality labels together with the slp data. Values lower than 600 hPa or higher than 1,080 hPa and repetitive values for five days were labelled suspicious and have been left out of the analysis. Additionally, we used daily geostrophic wind speed to identify suspicious values. If the derived geostrophic wind speed exceeds 60 m/s, the involved slp values were compared to the surrounding spatial pressure pattern. In this way, twenty-five days have been identified for checking the slp pattern. For the period September 1957–August 2002, the suspicious data were compared to the spatial pattern according to the reanalysis slp data of ERA40 (Uppala et al. 2005). Eleven daily slp values have been labelled suspicious and were discarded; seven of them before ERA40 comparison (4x Aberdeen, 2x Esbjerg Airport, 1x Armagh) and four of them within the ERA40 comparison (4x Armagh).

The pressure time series have not been analysed for inhomogeneities, which might have resulted from changes in instrumentation or station relocations. Due to a lack of sufficient meta-data in the ECA&D database, it is not possible to distinguish between inhomogeneities and natural long-term variability. To filter out the influence of LTP, homogeneity testing is usually applied on a difference series with a strongly correlated series. However, for the long time series used in this study very few time series are available and the possible difference series are closely related to pressure gradients and so to geostrophic wind speed. Since we expect geostrophic wind to be subject to LTP, we expect this for the difference series too. Rather than homogeneity testing we performed a sensitivity analysis to inhomogeneities in the slp time series, due to (unknown) station relocations, sudden shifts (e.g. unrecorded height displacements) and changes in recording time of frequency.

2.1.1 Station relocations

Two slp series are very likely to be continuations of older nearby stations, although this was not found in the meta-data of the ECA&D database. The annual mean slp values of Thyboron and Esbjerg Airport are very similar to Vestervig and Nordby (1874–1986) respectively, which are both available until 1986. Alexandersson et al. (1998) reported relocations between 1986 and 1987 for both pairs of stations. Applying Alexandersson’s coordinates rather than the ECA&D coordinates helps to remove an obvious inhomogeneity in the geostrophic wind speed series derived from the slp series of Thyboron, Esbjerg Airport and Hammer Odde Fyr.

The use of incorrect, but nearby (<20 km) coordinates only causes obvious inhomogeneities in geostrophic wind speed for the relatively small triangle Thyboron-Esbjerg Airport-Hammer Odde Fyr. Consequently, the estimated Hurst exponent (H) appeared much higher for fixed coordinates, i.e. neglecting station relocations. For the larger triangles, the influence is relatively minor.

2.1.2 Sudden shifts

The impact of sudden shifts in the slp series was studied by perturbing the second half of one of the three stations with an amount of 0.25 hPa, which is small enough to be overlooked by visual inspection. It appeared that such small shifts rarely affect the estimation of H in time series of geostrophic wind speed.

According to ECA&D, the slp in Aberdeen is on average 0.87 hPa higher than the nearby station Dyce (at a distance of 8.0 km). To avoid inhomogeneities in geostrophic wind derived from a combined slp series, Aberdeen was corrected before. Subtracting the difference in mean slp from the slp values of Aberdeen removes most of the inhomogeneity.

2.1.3 Changes in recording time

The remaining inhomogeneity might be caused by the fact that the Dyce data represent daily mean slp between 23–23 UT and the Aberdeen data represent 0–0 UT. This inhomogeneity, however, is small and hardly affects estimated \(\hat{H}\).

For the Norwegian stations Bergen Florida and Bodø VI two types of daily slp are available. The first represents daily mean slp between 0–0UT and the second represents daily mean slp between 18–18UT (see Table 2). The 0–0UT time series start much earlier (1868) than the 18–18UT time series (1901), but the Bodø series is only available until 1995 and Bergen until 2002. Replacement of Bodø 0–0UT by 18–18UT hardly affects the annual variability and estimated \(\hat{H}\) and Bodø can safely be extended by the 18–18UT series. For Bergen the influence of such replacement depends on the triangle. Replacement does affect U ECA and \(\hat{H}\) for the triangles Bodø-Bergen-Torshavn, Bodø-Bergen-Thyboron and Esbjerg-Torshavn-Bergen. For the triangles Aberdeen-Torshavn-Bergen and Bergen-Aberdeen-Thyboron, Bergen slp is extended by the 18–18UT series. The slp data (0–0UT) of Stykkisholmur are available until 2002 and extended until 2008 by synops data (18–18UT).

2.1.4 1900

In 1900, the cross correlation structure of daily slp between the Norwegian stations Bodø and Bergen with other stations is shifted in time with respect to the cross correlation for the whole period. In general, the highest correlation between daily slp of two nearby stations is found at the same day. In 1900, however, the highest correlation is found at lag 1. This shift in cross correlation structure results in way too high U ECA . Although the cause of this shift has not been retrieved, the year 1900 is discarded from the Bodø and Bergen time series.

2.2 ESSENCE

In the ESSENCE project, an ensemble of seventeen simulations with the ECHAM5/MPI-OM climate model (Jungclaus et al. 2006) with common evolution of the boundary conditions and only slightly varying initial conditions was performed (Sterl et al. 2008). Differences between the ensemble members are caused by internal variability of the simulated climate. An ensemble of climate model simulations therefore gives the opportunity to investigate very rare events, such as extreme rainfall (Sterl et al. 2009) and to analyse decadal variability which typically demands long time series.

ECHAM5/MPI-OM fairly well reproduces the observed mean and multi-decadal slp patterns for all months, as well globally as in Europe (Van Ulden and Van Oldenborgh 2006). In winter, also the general circulation in western and central Europe is realistically covered (Demuzere et al. 2009) despite the slightly underestimated variability (Van Ulden and Van Oldenborgh 2006). Summer, however, gives too much westerly flow (Van Ulden and Van Oldenborgh 2006; Demuzere et al. 2009).

The climate model runs on a regular grid at a spatial resolution of about 200 × 200 km2. The integrations follow observed GHG concentrations and tropospheric sulphate for the initialisation and historical part (1950–2000) and the SRES A1B emission scenario (Nakicenovic et al. 2000) for the future period 2001–2100. Volcanic eruptions and variations of the solar constant have not been taken into account, although they may be important contributors for long-term variability (Vyushin et al. 2004). A long initialising period has been applied. The different ensemble members were generated by disturbing the initial atmospheric temperature field with Gaussian noise of amplitude 0.1 K. The initial ocean state was not disturbed. In this way, all members represent the same deterministic trend due to increased GHG concentrations and tropospheric sulphate and mutual independent natural (multi-year) variations.

The slp output was stored at a 3-hr temporal resolution at every grid point. Geostrophic wind speed was derived using the slp-gradient between the four surrounding grid points. Thereafter, geostrophic wind speed was averaged to annual values.

3 Estimation of the Hurst exponent and long-term variability

3.1 Methods for Hurst estimation

Although estimates for the Hurst exponent (H) and the standard deviation (σ) of a time series are mutually dependent, most methods estimate H individually. In 2011, Tyralis and Koutsoyiannis compared three methods that do simultaneously estimate H and σ; LSSD (least squares based on standard deviation, Koutsoyiannis 2003), the LSV (least squares based on variance) and the ML method (maximum likelihood, McLeod and Hipel 1978). The three methods appeared to outperform nine classical methods including DFA1 (detrended fluctuation analysis, Peng et al. 1994). Higher order DFA methods (Kantelhardt et al. 2001) were not considered.

Tyralis and Koutsoyiannis (2011) indicated ML as the most attractive method method because of its high precision with respect to alternative methods and because σ is estimated simultaneously. The relative longer computation time will stay within acceptable limits since the records are not very long (n < 1,000). An additional advantage of ML is that the estimated likelihood function enables to include the parameter uncertainty in the estimation of the prediction level for future mean aggregated geostrophic wind speed (see Sect. 5.1.2).

In Sect. 3.2 the implementation of the ML method is explained and it is shown that the estimated \(\hat{H}\) is biased. Therefore, we slightly adjusted the ML method in Sect. 3.3. Section 3.4 explains the trend estimation and detrending. In Sect. 3.5, the spatial pattern of \(\hat{H}\) is shown and interpreted.

3.2 Maximum likelihood estimation

For the estimation of the Hurst exponent (H) we slightly adapted the maximum likelihood method (ML) as proposed by McLeod and Hipel (1978). Tyralis and Koutsoyiannis (2011) found a very good performance of this method compared to other methods and emphasised the advantage that the three parameters μ, σ and H are estimated simultaneously.

Given a historical time series u n = [u 1, …, u n ] of annual average geostrophic wind speed u i of length n, the log-likelihood (logL) of \(\varvec{\theta}=[\mu,\sigma,H]\) is

where C N (H) is the n × n autocorrelation matrix [ρ|i-(i+j)|] which depends on H and lag j—not on the aggregation level k—via

Tyralis and Koutsoyiannis (2011) showed that the ML estimates of μ and σ are

with \({e}=[1,1, \ldots, 1]\) is an n-element vector. Substituting Eqs. 6 and 7 in Eq. 4 gives

The ML estimate \(\hat{H}\) is found by maximising g(H)

For typical sample sizes of annual mean geostrophic wind speed (n = 80–150) the estimates \(\hat{H},\,\hat{\sigma}\) and as a consequence \(\hat{\sigma}^{(10)}\) are biased. Figure 2 shows the spread (1,000 samples) of the ML estimates for given H = 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 and 0.9 and σ = 1.0 for sample sizes n = 50, 100, 150 and 200. The samples are generated by a “quick and dirty” algorithm (Multiple Time Scale Fluctuation Approach), which efficiently approaches Fractional Gaussian Noise (Koutsoyiannis 2002).

Boxplots (estimated of 1,000 samples) of ML-estimates for different true H (x-axis) and sample sizes (colours). The boxes represent the 1st and 3rd quartile, the black line the median and the whiskers the 5 and 95% quantiles. The underlying horizontal black line elements give the true values. Left: ML estimate \(\hat{H}\), centre: ML estimate \(\hat{\sigma}^{(1)}\) and right: ML estimate \(\hat{\sigma}^{(10)}\)

3.3 Adaptation maximum likelihood method

The negative bias is possibly a manifestation of the fact that the sample autocorrelation is a biased estimate for the true population autocorrelation for small sample sizes and H > 0.5. Therefore, the likelihood of a certain H should be based on lower correlations than in the matrix C N (H). For this purpose, the correlations are calculated by applying an adapted H in Eq. 5, expressed as H *.

which is valid for sample sizes between 50 and 200.

The use of the adapted H * considerably improves the ML estimates (ML+). The biases in \(\hat{H}\) disappear and the estimates \(\hat{\sigma}\) are exactly the same as for the original ML method. So, \(\hat{\sigma}^{(10)}\) also improves (Fig. 3).

As Fig. 2, but ML+ estimates instead of the original ML method

3.4 Trends and detrending time series

Since an apparent structural trend can be a manifestation of LTP, Hurst estimates for time series affected by trends are generally positively biased and vice versa. Therefore, the ECA&D annual geostrophic wind speed (U ECA ) series were tested for trends and if necessary detrended before evaluating LTP. Figure 4 shows the linear trends according to Sen’s non parametric trend estimator (Sen 1968).

Most of the regarded geostrophic wind speed time series do not show significant trends according to the ordinary Mann–Kendall (MK) trend test. The trends of two triangles, in front of the Norwegian coast, were tested significant using ordinary MK, but the trends turned out not to be significant using MK adapted for LTP (Hamed 2008). The geostrophic wind speed of two triangles, Aberdeen-Armagh-Torshavn & Aberdeen-Armagh-De Bilt, shows a significant decrease according to both trend tests and had been detrended before estimation of H.

3.5 Hurst exponent in ECA&D geostrophic wind speed time series

The Hurst exponent was estimated by the adapted maximum likelihood (ML+) method. The presence of missing values only introduces a minor bias and slightly wider confidence intervals, but Eq. 10 remains valid. Therefore, missing values were simply omitted as they do not add any information. The number of values (n) should be interpreted as the sum of valid and missing values where the first and last value of the series should be valid.

The confidence levels of the Hurst exponent were determined for every geostrophic wind speed time series separately by a Monte Carlo simulation (MC) using 1,000 stochastically generated time series. The MC took into account the time series length and the distribution in time of missing values. The significance of the Hurst phenomenon (H > 0.5) was tested one-sided at a 5% confidence level (Fig. 5).

The estimated Hurst exponents show a spatially coherent picture. The geostrophic wind speed derived for the triangles over the North Sea, British Islands and along the Scandinavian coast are characterised by a significant Hurst exponent between 0.58 and 0.69. The origin of this pattern is not clear.

4 Long-term variability in ESSENCE

4.1 Reproduction of past climate by ESSENCE

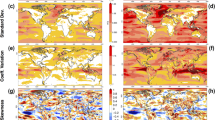

The ESSENCE simulations fairly well reproduce the ERA40 long-term mean slp patterns over North Europe between 1958 and 2002. Even in an absolute sense the differences are relatively small (Fig. 6). However, the Iceland low appears a little too deep and pressure gradients towards the southeast are generally too strong.

The difference between ERA40 and ESSENCE year-to-year variability of slp is characterised by a distinct north-south gradient (Fig. 7). The northern part of the domain is characterised by a considerable overestimation and the central southern part by an underestimation, both more than two times the standard deviation of the 17 standard deviations within the 17 individual simulations (shaded area). This suggests that the spatial pattern in the difference is not arbitrary.

Standard deviation of annual mean sea level pressure (ERA40) [hPa] (left) and difference (ESSENCE—ERA40) in standard deviation of annual mean slp [hPa] (right). Dark shaded area in right panel indicates that the difference is more than two times larger than the standard deviation of the 17 standard deviations within the 17 individual simulations

The general spatial pattern of annual mean geostrophic wind speed according to ESSENCE U ESS resembles U ERA40 well (Fig. 8, left). However, ESSENCE gives generally too high geostrophic wind speed and completely misses local minima such as in the south of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The overestimation of the geostrophic wind speed is partly caused by the slightly higher spatial resolution of ESSENCE. But the main cause is probably the too high mean slp gradient in ESSENCE. The coefficient of variation (CV) is strongly underestimated by up to 40% for the largest part of the investigated area. Only the northwestern and southeastern corner are overestimated.

4.2 Trend testing and detrending

Before estimating and significance testing of H in the ESSENCE ensemble, the geostrophic wind speed series have been tested for trends and were detrended accordingly. Figure 9 (left) shows the median trend between two arbitrary points in time (Sen’s trend estimator, Eq. 11) in the ESSENCE ensemble together with its significance. To minimise the possible influence of LTP, the significance testing is done by the application of the ordinary MK test to the ensemble mean. According to this test, the ESSENCE ensemble of climate simulations shows small, but significant trends between 1950–2100 in large parts of northern Europe.

The northwestern part of the investigated domain is characterised by a strong non-linear decrease of U ESS , starting between 2000 and 2010. However, the farmost northwestern corner (over Greenland) shows even stronger increasing trends. The strong spatial gradient of temporal trends between Iceland and Greenland could be the result of the changes in sea ice cover in the ESSENCE simulations during the twenty-first century. The strong retreat in winter and even disappearance in summer of sea ice in the Denmark Strait (not shown) may strongly affect the prevailing surface temperature gradients and as a consequence pressure gradients in these areas.

The 17 individual member simulations have been detrended prior to the estimation and testing of H. This is done by subtracting the smoothed ensemble mean because this ensemble mean appeared still rather noisy. The smoothing is done by taking the 21-year moving average.

4.3 Estimation of the Hurst exponent for the ESSENCE ensemble

The Hurst exponent of the ensemble simulations was determined using the same procedure as used for the ECA&D data and taking the median of the estimates of all ensemble members. Extension of the procedure for an ensemble of mutually independent time series is very time-consuming and turns out to give similar results.

The estimated \(\hat{H}\) in the ESSENCE simulations are generally close to 0.5 and not significant (Fig. 9, right). About 5% of the shown area is tested significant which likely originates from statistical coincidence. Yet, the significant area near Greenland substantially extends in both directions along the coast and into the Greenland Sea/Arctic ocean (not shown). Similar to the decrease of U ESS in the same area, this is likely to be caused by variations in sea ice cover, which is highly persistent between years.

5 Prediction intervals of multi-year geostrophic wind

5.1 Stochastic intervals

5.1.1 The Hurst phenomenon and natural climatic variability

In case of LTP, the variability of the multi-year aggregated mean of a process dramatically increases with the length of the averaging interval compared to classical statistics. For the aggregation level k, the standard deviation of the aggregated mean is given by the general law \(\sigma^{k}=\frac{\sigma}{k^{(H-1)}}\) (Eq. 2). It can be justified to assume predicted annual geostrophic wind speed (U (1)) approximately normally distributed (and thus U (10) too). So, the prediction limits can be calculated by multiplying σ(10) by the b-quantile of the standard normal distribution \((\zeta_{b})\). These (unconditional) prediction limits are valid for long lead times, i.e. the far future where the influence of observed u n is limited. For shorter lead times, the past information cannot be neglected. We used the approximation for the conditional intervals derived by Koutsoyiannis et al. (2007) to take the past observatios into account (see “Appendix”). The approximation is derived for sample size n = 100, but our records are of comparable length.

5.1.2 Parameter uncertainty

The prediction interval for future aggregated mean geostrophic wind speed depends on several sources of uncertainty. The measurement uncertainties have not been considered in this study, since the influence of this uncertainty is fairly low if the gestrophic wind triangles are chosen large enough (see Sect. 2). Uncertainty due to climate variability can be well quantified when the Hurst exponent (H) is known. Yet, H is very uncertain for sample sizes smaller than n = 200 (Fig. 3) and this uncertainty should be taken into account.

Climate variability and parameter uncertainty can be combined in a Bayesian way (Gelder 2000). According to Bayes theorem (Bayes 1763), describing the conditional probability, the posterior density of \(\varvec{\theta}=[\mu,\sigma,H]\) can be written as

where

- \(\pi(\varvec{\theta}|{\bf u}_{\bf n})\) :

-

the posterior density of \(\varvec{\theta}=[\mu,\sigma,H]\) after observing \({\bf u}_{\bf n}=(u_{1},\dots,u_{n})\),

- \(l({\bf u}_{\bf n}|\varvec{\theta})\) :

-

the likelihood function of the observations for known \(\varvec{\theta}=[\mu,\sigma,H]\) (see Eq. 4),

- \(\pi(\varvec{\theta})\) :

-

the prior density of \(\varvec{\theta}=[\mu,\sigma,H]\) before observing \({\bf u}_{\bf n}=(u_{1},\dots,u_{n})\) and

- \(\pi({\bf u}_{\bf n})=\int_{\varvec{\theta}}l({\bf u}_{\bf n}|\varvec{\theta})\pi(\varvec{\theta})\mathsf{d}\varvec{\theta}\) :

-

the marginal density of the observations, which can be considered as a normalising constant.

Obviously, the posterior density strongly depends on the subjective choice of the prior density. In this study we have chosen μ and σ fully dependent on H. This choice is justified since estimates for the parameters σ and H are closely related and the uncertainty of μ hardly influences the total uncertainty (Tyralis and Koutsoyiannis 2011). Given H, the ML method of Eqs. 6 and 7 was used to estimate μ and σ. For the prior density of H, the uniform distribution was used, bounded by 0.5 and 0.99. The lower boundary is chosen 0.5, since we do not think that H < 0.5 (i.e. antipersistence or negative autocorrelation) is likely to be met for annual geostrophic wind speed across northwestern Europe.

5.2 Deterministic intervals

The ESSENCE prediction intervals up to 2100 of the 10-year aggregated mean geostrophic wind speed (U (10) ESS ) have been constructed by exploiting the assumed mutual independency of the 17 simulations. For every ECA&D triangle, the ESSENCE grid box closest to the triangle center was chosen. Next, the 17 time series (1950–2000) of the annual mean geostrophic wind speed U (1) ESS were scaled such that the sample annual mean and standard deviation correspond to the sample characteristics of U (1) ECA . Then, for every year (1959–2100), the 10-year aggregated mean U (10) ESS was calculated for all members separately. The ensemble mean is used as the central prediction. A first order estimate of the 95%-prediction interval is obtained from the 17 values per year. This first order estimate is very noisy since the sample of 17 members is rather small. Therefore, this prediction interval is smoothed by taking the 21-year moving average. The obtained intervals fairly well represent climatic variability and the deterministic trend due to changed greenhouse gas concentrations represented by the ESSENCE simulations.

5.3 Comparison intervals

The evolution in time of U (10) ESS and its accompanying prediction intervals are compared to the previously discussed intervals derived from the historical time series u n :

-

classical prediction intervals (see Eq. 3)

-

prediction intervals for known H (see Sect. 5.1.1 and “Appendix”).

-

prediction intervals for uncertain H (see Sect. 5.1.2).

Figure 10 explains on the basis of the ECA&D triangle Aberdeen-Torshavn-Bergen which intervals are represented by the different lines as used in the graphs in Fig. 11. The thick black line represents the observed 10-year running mean U (10) ECA , the blue line the future central prediction of the running mean \(U^{(10)\ast}\) and the dashed blue lines the future prediction intervals. The thin gray lines represent the evolution in time (1959–2100) of U (10) ESS according to the seventeen ESSENCE simulations and the green lines are the ensemble mean (solid) and the ESSENCE prediction intervals (dashed). The unconditional prediction intervals are given by the gray, dashed lines; light-gray according to classical statistics (H = 0.5), dark-gray taking into account known H and black taking into account the uncertainty of H.

Past 10-year running mean of geostrophic wind speed together with diverse 95%-prediction intervals for future 10-year running mean. Lines are explained in Fig. 10

The incorporation of LTP gives substantially larger prediction intervals than according to classical statistics (26% for H = 0.6 and even 100% for H = 0.8 at an aggregation level of k = 10). The uncertainty of the estimated \(\hat{H}\) accounts for an additional widening of the prediction intervals. For the time series of around 90 years this widening (absolutely) amounts 17–20% with respect to the classical estimates. This rapidly reduces to about 10% for time series of approximately 110 years and longer.

The central prediction \(U^{(10)\ast}\) based on the ECA&D annual mean geostrophic wind (U (1) ECA ) nearly equals the estimated population mean for lead times longer than the aggregation level (l > k). For shorter lead times, \(U^{(10)\ast}\) is partly averaged from observed (thus known) annual averages. As a result, the prediction interval starts relatively narrow and rapidly widens until l = k. After that, the prediction interval gradually approaches the (unconditional) prediction interval since the autocorrelation of u n slowly decreases with increasing lead time.

The ESSENCE prediction intervals are smaller than the intervals derived from past geostrophic wind speed u 0,n . This should be attributed to the underestimation of H (Sect. 4, Fig. 9), since the annual mean geostrophic wind U (1) ESS was scaled and shifted such that its characteristics (mean and standard deviation) match the U (1) ECA characteristics. In the southern part of the domain even the significant trends (e.g. De Bilt-Armagh-Thyboron and Thyboron-Esbjerg Airport-Hammer Odde Fyr) are negligible compared to the large prediction intervals. In the two most northern triangles (Tasiilaq-Jan Mayen-Stykkisholmur; Jan Mayen-Torshavn-Bodoe) U ESS is characterised by a strong decrease (see Sect. 4.2).

6 Discussion

The Hurst phenomenon or LTP has been detected in time series of geostrophic wind speed over the North Sea and British islands. The presence of LTP strongly increases the uncertainty of future long-term mean wind climate compared to assuming temporal independence. Most common methods underestimate the Hurst exponent and thus the multi-year variability in case of sample sizes smaller than 100–150 years. A minor adjustment of the ML method removes those biases. However, the uncertainty of the estimated Hurst exponent (and multi-year variability) remains large. The influence of this parameter uncertainty can be taken into account in a Bayesian way.

Geostrophic wind speed is a suitable proxy for the current wind climate, but inhomogeneities in the underlying pressure data may seriously affect the derived geostrophic wind speed. The meta-data as provided with the ECA&D pressure observations is limited, but it appeared that the influence of undetected inhomogeneities is small if the area to determine the geostrophic wind was chosen large enough. Even if large areas are applied, changes in recording time may result in significant shifts in derived geostrophic wind speed and thus the estimated Hurst exponent. These areas where changes in recording time may affect the results are identified. It is unlikely that unreported and undetected inhomogeneities significantly affected our results.

Our approach of estimating the prediction intervals on the basis of historical time series is only suitable for a fairly stable climate (including multi-year variations). For structural changes deterministic models such as GCM are indispensable. The existence of a seventeen member ensemble of simulations with ECHAM5 (SRES A1B) within the ESSENCE project enabled us to distinguish between structural trends and LTP. In general, the mean and interannual variability of slp and geostrophic wind speed are fairly well captured by ESSENCE. Yet, LTP was generally not reproduced. ESSENCE prediction intervals are therefore much smaller than the prediction intervals derived from observations.

The ESSENCE simulations produce significant trends in some areas within the investigated domain. In the southern part of the domain these trends are very small compared to the large multi-year variability, but the area north of Iceland is characterised by a strong non-linear decrease of geostrophic wind speed. This trend could possibly be attributed to changes in sea ice coverage. Pressure gradients are often related to gradients in surface temperature, which strongly depends on the presence of sea ice.

The ESSENCE ensemble of GCM simulations effectively helps to distinguish multi-year variability from structural trends. Ideally, comparable ensembles from other GCMs and other scenarios should be used to take model uncertainties and uncertainties about future emissions into account. However, such ensembles are very rare and GCM simulations usually do not capture LTP.

Despite the distinct effect of mesoscale roughness on the wind energy supply over land, we did not consider changes in surface roughness. In practice, it is very hard to predict changes in surface roughness and so to estimate its influence on wind supply. A scenario approach could be considered to cope with this important source of uncertainty.

The large multi-year variability of wind climate enlarges the uncertainty of projected near and far future multi-year wind energy yields. Since LTP cannot be estimated from the relatively short time series with surface wind speed and wind yields, LTP should be estimated from some large-scale circulation indicator of which long records can be constructed. The translation of LTP in geostrophic wind speed to LTP in wind energy yields is rather straightforward and needs some more investigation. The triangles over which the geostrophic wind speed was derived are very large. It is evident that the LTP in wind climate is not homogeneous within the entire triangle and the LTP calculated will probably not be representative for all parts of the area. The equally long time series, like pressure tendency (pressure difference between two successive days) do not suffer from this problem and should therefore be analysed too.

References

Albers A (2004) Long term variation of wind potential: are we moving into a low NAO-cycle period? In: European wind energy conference & exhibition, London, UK

Alexander L, Tett S, Jonsson T (2005) Recent observed changes in severe storms over the United Kingdom and Iceland. Geophys Res Lett 32:L13704. doi:10.1029/2005GL022371

Alexandersson H, Schmith T, Iden K, Tuomenvirta H (1998) Long-term variations of the storm climate over NW Europe. Glob Atmos Ocean Syst 6:97–120

Alexandersson H, Tuomenvirta H, Schmith T, Iden K (2000) Trends of storms in NW Europe derived from an updated pressure data set. Clim Res 14:71–73

Bakker A, Bessembinder J (2009) Wind energy in a changing climate. In: 9th EMS/9th ECAM, EMS annual meeting abstracts

Bakker A, Van den Hurk B, Coelingh J (2011) Decomposition of the windiness index in The Netherlands for the assessment of future long-term wind supply. Wind Energy (in review)

Bayes T (1763) An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 53:370–418 (reprinted)

Demuzere M, Werner M, Van Lipzig N, Roeckner E (2009) An analysis of present and future ECHAM5 pressure fields using a classification of circulation patterns. Int J Climatol 29(12):1796–1810. doi:10.1002/joc.1821

Gelder P (2000) Statistical methods for the risk-based design of civil structures. PhD thesis, Delft University of Technology

Hamed K (2008) Trend detection in hydrologic data: the Mann–Kendall trend test under the scaling hypothesis. J Hydrol 349(3–4):350–363

Hurst H (1951) Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans Am Soc Civ Eng 116(770–799):35

Jungclaus J, Botzet M, Haak H, Marotzke J, Mikolajewicz U, Roeckner E, Keenlyside N, Latif M, Luo J (2006) Ocean circulation and tropical variability in the coupled model ECHAM5/MPI-OM. J Clim 19:3952–3972

Kaas E, Li T, Schmith T (1996) Statistical hindcast of wind climatology in the north Atlantic and northwestern European region. Clim Res 7:97–110

Kantelhardt J, Koscielny-Bunde E, Rego H, Havlin S, Bunde A (2001) Detecting long-range correlations with detrended fluctuation analysis. Phys A 295:441–454. doi:10.1016/S0378-4371(01)00144-3

Klok E, Klein Tank A (2008) Updated and extended European dataset of daily climate observations. Int J Climatol 29(8):1182–1191

Knight W, Harrison C (2006) Weakness exposed in wind index system. Windpower Monthly

Koutsoyiannis D (2002) The Hurst phenomenon and fractional Gaussian noise made easy. Hydrol Sci J 47(4):573–595

Koutsoyiannis D (2003) Climate change, the Hurst phenomenon, and hydrological statistics/changement climatique, phénomène de Hurst et statistiques hydrologiques. Hydrol Sci J 48(1):3–24

Koutsoyiannis D (2006) Nonstationarity versus scaling in hydrology. J Hydrol 324(1–4):239–254

Koutsoyiannis D, Cohn T (2008) The Hurst phenomenon and climate. In: EGU General Assembly 2008. Geophys Res Abstr

Koutsoyiannis D, Efstratiadis A, Georgakakos K (2007) Uncertainty assessment of future hydroclimatic predictions: a comparison of probabilistic and scenario-based approaches. J Hydrometeorol 8:261–281

Koutsoyiannis D, Mamassis N, Christofides A, Efstratiadis A, Papalexiou S (2008) Assessment of the reliability of climate predictions based on comparisons with historical time series. In: EGU General Assembly 2008. Geophys Res Abstr

Matulla C, Schöner W, Alexandersson H, von Storch H, Wang X (2008) European storminess: late nineteenth century to present. Clim Dyn 31(2):125–130

McLeod A, Hipel K (1978) Preservation of the rescaled adjusted range, a reassessment of the Hurst phenomenon. Water Resour Res 14(3):491–508

Najac J, Boé J, Terray L (2009) A multi-model ensemble approach for assessment of climate change impact on surface winds in France. Clim Dyn 32(5):615–634

Nakicenovic N, Alcamo J, Davis G, de Vries B, Fenhann J, Gaffin S, Gregory K, Grubler A, Jung T, Kram T et al (2000) Special report on emissions scenarios: a special report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge

Peng C, Buldyrev S, Havlin S, Simons M, Stanley H, Goldberger A (1994) Mosaic organization of dna nucleotides. Phys Rev E 49(2):1685

Pryor S, Barthelmie R (2003) Long-term trends in near-surface flow over the Baltic. Int J Climatol 23(3):271–289

Pryor S, Barthelmie R, Kjellström E (2005) Potential climate change impact on wind energy resources in northern Europe: analyses using a regional climate model. Clim Dyn 25(7):815–835

Pryor S, Schoof J, Barthelmie R (2006) Winds of change? Projections of near-surface winds under climate change scenarios. Geophys Res Lett 33(11):L11702

Rockel B, Woth K (2007) Extremes of near-surface wind speed over Europe and their future changes as estimated from an ensemble of RCM simulations. Clim Change 81:267–280

Rutten M (2008) Persistence in precipitation time series from AR4 general circulation models for historical and future time slices. In: EGU General Assembly 2008

Rybski D, Bunde A, Von Storch H (2008) Long-term memory in 1000-year simulated temperature records. J Geophys Res 113(D2):D02106. doi:10.1029/2007JD008568

Schmith T, Kaas E, Li T (1998) Northeast Atlantic winter storminess 1875–1995 re-analysed. Clim Dyn 14:529–536

Segers R (2009) Windex op basis van productiedata van het CBS afgeleid uit registratie van CertiQ. Technical report, Statistics Netherlands/CBS, The Hague. http://www.cbs.nl (in Dutch)

Sen P (1968) Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J Am Stat Assoc 63(324):1379–1389

Sterl A, Severijns C, Dijkstra H, Hazeleger W, van Oldenborgh G, van den Broeke M, Burgers G, van den Hurk B, van Leeuwen P, van Velthoven P (2008) When can we expect extremely high surface temperatures. Geophys Res Lett 35:L14. doi:10.1029/2008GL034071

Sterl A, Vanden Brink H, Vries H, Haarsma R, Van Meijgaard E (2009) An ensemble study of extreme storm surge related water levels in the North Sea in a changing climate. Ocean Sci 5(3):369–378

Tyralis H, Koutsoyiannis D (2011) Simultaneous estimation of the parameters of the Hurst-Kolmogorov stochastic process. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 25(1):21–33. doi:10.1007/s00477-010-0408-x

Uppala S, Kållberg P, Simmons A, Andrae U, Bechtold V, Fiorino M, Gibson J, Haseler J, Hernandez A, Kelly G et al (2005) The ERA-40 re-analysis. Q J R Meteorol Soc 131(612):2961–3012

Van Ulden A, Van Oldenborgh G (2006) Large-scale atmospheric circulation biases and changes in global climate model simulations and their importance for climate change in central europe. Atmos Chem Phys 6:863–881

Vautard R, Cattiaux J, Yiou P, Thépaut J, Ciais P (2010) Northern hemisphere atmospheric stilling partly attributed to an increase in surface roughness. Nat Geosci 3(11):756–761

Von Storch H, Navarra A (1995) Analysis of climate variability: applications and statistical techniques. Springer, Berlin.

Vyushin D, Govindan R, Brenner S, Bunde A, Havlin S, Schellnhuber H (2002) Lack of scaling in global climate models. J Phys Condens Matter 14:2275. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/9/316

Vyushin D, Zhidkov I, Havlin S, Bunde A, Brenner S (2004) Volcanic forcing improves atmosphere-ocean coupled general circulation model scaling performance. Geophys Res Lett 31. doi:10.1029/2004GL019499

Wang X, Zwiers F, Swail V, Feng Y (2009) Trends and variability of storminess in the Northeast Atlantic region, 1874–2007. Clim Dyn 33(7–8):1179–1195

WASA G (1998) Changing waves and storms in the Northeast Atlantic? Bull Am Meteorol Soc 79:741–760

Wever N (2011) Quantifying trends in surface roughness and the effect on surface wind speed observations. J Geophys Res (in review)

Woth K, Weisse R, von Storch H (2006) Climate change and North Sea storm surge extremes: an ensemble study of storm surge extremes expected in a changed climate projected by four different regional climate models. Ocean Dyn 56(1):3–15

Acknowledgments

This study was done as part of the project “Cs7—Tailoring Climate Information” within the research Programme “Climate changes Spatial Planning”. We worked closely together with Jan Coelingh of Ecofys, who taught us which climate-related questions are really important for wind engineers. We want to thank Janette Bessembinder and Gerard van der Schrier for reading and commenting on the manuscript. We also want to thank Andrew Stepek for checking the English. Finally, we want to thank the ECA&D-team and the ESSENCE staff for helping us to interpret and access the data we used in this research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Approximation conditional climatic expectation

Appendix: Approximation conditional climatic expectation

For sample size n, Koutsoyiannis et al. (2007) derived the following approximations for the conditional climatic expectation and the conditional standard deviation of U (k) l (Eqs. 13, 16)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakker, A.M.R., van den Hurk, B.J.J.M. Estimation of persistence and trends in geostrophic wind speed for the assessment of wind energy yields in Northwest Europe. Clim Dyn 39, 767–782 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-011-1248-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-011-1248-1