Abstract

We experimentally test the effect of aggressive audit strategies on tax compliance. Taxpayers first go through a phase of audits managed by a human tax agent who is requested to follow a rule imposed by a fair random device. However, the tax agent can freely decide to break the rule and over-inspect. Afterward, taxpayers are exposed to a genuinely random audit process governed by an algorithm, which makes compliance a strategically dominated option. We find that taxpayers are generally over-inspected by the human tax agents and react to this with nearly full compliance. Our main result is that these high levels of compliance also persist when controls are implemented by the algorithm. This suggests that tax authorities can use aggressive audit strategies to raise and sustain tax compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Legal and economic considerations usually constrain state measures to fight tax evasion. In some cases, audits are determined based on sophisticated computer algorithms that can detect discrepancies or construct risk profiles based on tax returns. In other cases, tax authorities target taxpayers according to observable characteristics, like their profession or domicile.Footnote 1

Periods of intensive controls are a widely discussed tool for preventing crime (Sherman 1990; Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2003; Kleiman 2009; Eeckhout et al. 2010). Auditing specific categories or groups more intensively may help a tax authority coordinate its efforts for a given period. Those targeted by these policies might increase their compliance temporarily to avoid sanctions. However, they might also feel unjustly treated, e.g., compared to taxpayers in similar categories or other locations who are not inspected with the same intensity. This could lead such policies to backfire, as taxpayers could stop complying once the pressure is reduced or start misbehaving in other contexts, e.g., by not pay other kinds of taxes.Footnote 2 What are the effects of these policies? Do taxpayers become more compliant both while and after they are targeted?

We investigate both the dynamic evolution of tax compliance under aggressive audit policies and how these policies affect tax compliance once the pressure on taxpayers is alleviated. In our experiment, taxpayers are asked to contribute repeatedly to a public project that generates indistinct benefits to the group of contributors.Footnote 3 Tax agents are instructed to implement inspections only when the roll of a fair die delivers a certain outcome. This sets a rule they are supposed to follow, deontologically. However, tax agents are free to misreport the outcome and implement as many inspections as they like and force taxpayers to comply. When a tax inspection is implemented, taxpayers are sanctioned with a fine proportional to the amount of taxes evaded. The reward of tax agents is experimentally manipulated and is either fixed (Flat) or proportional to the taxes paid (Contingent). We hypothesize that tax agents will break the rule and try to enforce high compliance with frequent inspections, if their monetary incentives outweigh their lying costs. However, our main focus is on how taxpayers respond to these inspections. Our prediction derived from a standard model is that they should fully comply if they perceive the probability of being inspected to be high enough. Taxpayers, then, go through a phase in which they face a fixed probability of being inspected. This recreates a situation in which pressure is reduced after a period of intensive audits. Fines are non-deterrent, as we want to look at potential spillover effects from the previous phase. More specifically, if taxpayers respond only to monetary incentives or feel that the pressure put on them was unjust, they could start evading to voice their disapproval. Alternatively, taxpayers might internalize the norm of high compliance and continue paying their taxes.

We find that, as expected, tax agents tend to violate the rule set by the random device and over-inspect their taxpayers. However, they do so irrespectively of their incentive scheme. Taxpayers who are more frequently inspected display a higher degree of tax compliance. Crucially, compliance stays high also when audits become random, and the expected impact of fines is not large enough to deter evasion, showing a positive spillover effect and no major backfire effect. Interestingly, tax agents can be classified into distinct types based on their auditing strategies. Some of them implement constant inspections, while others adopt more sophisticated strategies that teach taxpayers high compliance. Tax agents following the rule set by the random device never manage to discipline their taxpayers.

Our experiment offers a unique test-bed to investigate the effect of aggressive auditing policies on compliance. First, it allows us to track compliance levels precisely. Second, it enables us to get at the causal effects of policies that would be very hard to evaluate with real-world data. Our results suggest that aggressive audit strategies can be used to increase tax compliance and that, once high compliance is reached, tax authorities can release pressure without the fear of a backfire effect. We provide a more extensive discussion of the implications and limitations of our findings in the “Conclusion” (see Sect. 6).

2 Related literature

Tax compliance can be tackled from various perspectives, going from its behavioral determinants (see Kirchler et al. 2007, for a review) to its macroeconomic consequences. Similarly multifaceted are the methodological approaches, ranging from theoretical studies (see Allingham and Sandmo 1972; Srinivasan 1973; Yitzhaki 1974 for some of the first theoretical models) to field experiments (see, e.g., Fellner et al. 2013; Hallsworth et al. 2017). Laboratory experiments on tax compliance have by now a long-standing tradition (see Friedland et al. 1978; Alm 1991; Webley 1991, for early examples).Footnote 4 Early laboratory experiments were mainly employed to test theoretical models (see, e.g., Alm et al. 1992), but have now gained a more prominent role in the discipline (Alm and Jacobson 2007). Their internal validity and flexibility can offer broad insights into tax-paying behavior (Slemrod and Weber 2012). Work by Alm et al. (1999), for example, highlighted the importance of social norms in tax compliance, while that of Fortin et al. (2007) stressed the relevance of social interactions. Hence, if well designed, an experiment can be a valuable source of knowledge to understand tax compliance behavior (Alm 2012).

Our work is closely linked to experiments investigating the effect of different auditing schemes on compliance levels (for early work on this topic see, Mittone 1997). Research in this field has found two major regularities: the echo and the bomb crater effect (see Guala 2005; Mittone 2006). The bomb crater effect captures a drop in compliance observed after an inspection has taken place.Footnote 5 The echo effect refers to a regularity of behavior leading to higher overall compliance caused by repeated inspections placed in the early part of an individual’s taxpaying life. We provide an original contribution to this literature with the introduction of endogenously generated inspection schemes by a tax agent.Footnote 6

In a related study, Clark et al. (2004) compares random audits with different conditional audit schemes according to which participants are assigned to a “good” and a “bad” pool as a function of their past compliance. Conditional audit schemes increase compliance (on this see also, e.g., Cason et al. 2016). We analyze a different policy instrument since aggressive audit strategies are a temporary measure, which could, in principle, come on top of such conditional audit schemes. Dai et al. (2017) look at a similar policy in the context of fare-dodging and find that people tend to commit more fraud when crackdowns end. Galbiati et al. (2018), on the other hand, find that past fines, even if no longer in force, help sustain cooperation. Our study looks at tax compliance in a context in which taxes paid provides a collective benefit. Our work also offers a methodological innovation since these aggressive audit strategies are performed by humans.

To create a setup where a preset rule can be overturned by a tax agent, we rely on the die-under-the-cup paradigm (Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi 2013), which has extensively been adopted in the literature about truth-telling. The essential feature of this procedure is that the real outcome of the random device is known only to the participant rolling the die, leaving her completely free to choose what to report. According to the rule in the experiment, an inspection should take place whenever tax agents roll the number 3.Footnote 7 However, they are free to report whichever outcome they want. Abeler et al. (2019) review a large number of studies adopting this paradigm and find that, overall, participants do not lie as much as a purely selfish money maximizer would. We exploit these findings and expect to observe some, but not too many, departures from the preset audit rule. At the same time, the preset rule constitutes a reference point for taxpayers in our experiment, such that deviations therefrom naturally mimic a situation in which they are put under pressure.

3 Methodology

3.1 The tax game

Participants in the experiment are randomly assigned to one of two roles, Tax Agents (TA) and Tax Payers (TP)Footnote 8. Each TA is matched with 4 TPs, and together they constitute an independent group of 5 throughout the experiment (partner matching).

In each of the 30 rounds of the experiment, participants in the role of TPs are given an endowment \(E=100\) ECU (Experimental Currency Unit) and are asked to pay a tax t that contributes to a public project (tax rate of 30%)Footnote 9. The tax t is subtracted from E and can be freely chosen over the interval \(\{{\underline{T}}, 1 \ldots {\overline{T}}\}\), with \({\underline{T}}=0\) and \({\overline{T}}=30\) ECU. The taxes collected in a group of 4 TPs are multiplied by an efficiency factor \(\alpha =1.5\), and the result is equally divided among the four of them. This results in a marginal per-capita return (MPCR) of the projects equal to 0.375.

Before knowing the amount of taxes collected, the TA can decide to implement an inspection, as detailed below. If she chooses to do so, all TPs in her group are inspected. When a tax inspection is implemented, a fine F is paid by each TP. The size of F is given by the difference between the tax due \(({\overline{T}})\) and the amount actually paid t, multiplied by a penalty factor \(\phi =1.5\). Given this setting, the payoff of TPs is given by \(\Pi ^{TP}_{i}=E-t_i-C\bigl (({\overline{T}} -t_i)\phi \bigr ) + \frac{\alpha }{4}\sum _{j=1}^4 t_j\), where C is equal to 1 when an inspection is implemented, and to 0 when it is not.

The design of controls by TAs presents two main features: controls happen at the group level and are implemented before knowing the actual contribution level in the period. We adopted this design to improve the reading of inspection choices that do not depend upon the TPs’ specific behavior in a given round. Thus, decisions to inspect can only be conditional upon group behavior in previous rounds. In terms of realism, our setting captures a situation in which taxpayers in a given cluster are inspected, maybe because it is known from their past behavior that this target group is more likely to dodge taxes. Still, within the cluster, controls happen randomly without prior information about individual behavior.

3.2 Treatments

We experimentally manipulate two factors that affect the way inspections are implemented by the TA (see Table 1): in a within-subjects manipulation, we alter the mechanism governing the tax inspections (Inspection Rule), and in a between-subjects manipulation, we alter the payoff function of the TA (Inspection Incentives).

Concerning the Inspection Rule, in the first 20 rounds of the experiment, TAs are asked to roll a fair six-sided die and are instructed to perform a tax inspection when the outcome of the roll is equal to 3. Obviously, the probability of obtaining such an outcome is equal to 1/6. However, the roll of the die is privately performed, and participants are aware that no one in the room will be able to check if the actual outcome of the roll corresponds to the self-reported one (see Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi 2013).Footnote 10 This phase is labeled Human because the actual implementation of inspection rests upon the judgment of the TA: each TA can freely choose to report the outcome of the roll faithfully, as requested to do, or to report a different outcome, knowing that no sanction, neither monetary nor non-monetary, is associated to the misreporting. Note that TPs were aware of how TAs were instructed to act and of the procedure that determined inspections in this phase. In rounds 21–30, the inspection is performed by the computer (i.e., the Machine) in a genuinely random way with a probability of 1/6 in each round.Footnote 11 All participants learned about the two phases at the beginning of the experiment; this information was common knowledge.

Concerning the Inspection Incentives, in condition Contingent the TA earns an amount which is proportional to the sum of taxes paid by the TPs in her group.Footnote 12 Specifically, the payoff of the TA is given by \(\Pi _{TP}=\beta \sum _{j=1}^4 t_j\), where \(\beta =1.5\). Differently, in condition Flat, the payoff of the TA in each round is fixed and does not depend on the choices of the TPs in her group. (\(\Pi _{TP}=K\), with K equal to 100 ECU).Footnote 13 Note that the incentives of TAs as well as those of TPs were common knowledge.

3.3 Hypotheses

We start by analyzing TPs’ behavior since we want to understand how they react to aggressive audit strategies both when they are in place and when they are not anymore. A selfish risk-neutral TP is going to evade taxes fully, i.e., to set \(t={\underline{T}}\), as long as the likelihood of being inspected is \(P(C) \le 0.417\). At the other extreme, when \(P(C)> 0.417\), full tax compliance, i.e., \(t={\overline{T}}\), should be observed.

We now spell out our predictions for condition Human, where the level of compliance will depend on the expected inspection frequency of TAs. To understand TAs’ behavior, we should examine their payoff incentives. In condition Flat, where the payoff of a TA is not a function of TPs’ choices, we predict that she is going to report the outcome truthfully. This prediction is obtained under the assumption of weak preferences for truth-telling, i.e., TAs are going to report the truth as long as this comes at no material cost to them. Consequently, given that TAs truthfully report the actual outcome of the die, full tax evasion should be observed on the side of TPs.

Viceversa, in condition Contingent, the payoff of a TA is linearly increasing in the size of the public project. Thus, she strictly prefers an outcome of full compliance to all other outcomes. It can easily be shown that two possible equilibria in pure strategies may exist: one without inspection and full evasion (no inspection equilibrium) and one with inspection and full compliance (inspection equilibrium). It is worth noting here that the latter equilibrium is payoff dominant: in the inspection equilibrium, the payoffs of TPs are equal to 115 ECU, and that of the TA is equal to 180 ECU; in the no-inspection equilibrium, the payoffs are 55 ECU and 0 ECU, respectively.Footnote 14 Hence, we argue that over rounds, TAs will enforce a regime of full inspections, misreporting the outcome of the die roll. Anticipating this, TPs will fully comply in each round. We summarize our predictions in the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1a

TAs will misreport the outcome of the die and always inspect TPs in Contingent, while they will follow the indication of the die in Flat.

Hypothesis 1b

As a consequence, TPs will fully comply in Contingent and fully evade in Flat.

In condition Machine, i.e., when the roll of the die governs inspections, we predict full evasion. This is straightforward since \(P(C)=1/6 < 0.417\). In turn, this means that TA in condition Contingent/Machine will earn nothing.

Hypothesis 2

TPs will fully evade taxes in Machine.

From the standpoint of standard economic analysis, compliance levels in Human should not influence TPs’ behavior in Machine. However, potential spillover effects might lead to different results. On the one hand, if a norm of compliance has been established in Human, it might carry over in Machine and promote tax compliance. On the other hand, if TPs feel unjustly treated by TAs they might decide to evade taxes as a retaliatory measure. Our analysis investigates whether these spillovers from one phase to the other are in place.

For the sake of simplicity, we built our main hypotheses under the assumption of rational selfish preferences. On the side of TAs, deviations from these benchmark predictions may be observed if a psychological cost is associated with lying. This cost may originate either from moral or self-image concerns.Footnote 15 A psychological cost of lying may counteract the monetary incentives to misreport the outcome in condition Contingent. If the costs of lying are high enough, TAs may prefer to report the outcome of the die roll truthfully. The meta-study by Abeler et al. (2019) shows that people vary in how often they lie. Some refrain from lie maximally or constantly, achieving sub-optimal payoffs, and all possible outcomes are reported with positive probability. We expect this heterogeneity to play itself out in TAs’ inspection strategies (see Sect. 4.3 for an exploratory analysis of types). At the same time, TAs may also suffer from seeing a compliance norm violated by the TPs they are meant to inspect. This could push them to inspect more often and help them find a justification for lying. Non-standard preferences such as social preferences could also influence TPs’ behavior since the taxes paid generate a public good. In fact, individuals with a taste for efficiency (Engelmann and Strobel 2004) and/or a distaste for inequity (Fehr and Schmidt 1999) could possibly pay their taxes. However, standard public good experiments show that this is often not enough to sustain cooperation, especially in the long run (Fischbacher et al. 2001).

3.4 Participants and procedures

We conducted a total of 8 experimental sessions, 4 for each between-subjects treatment. The computerized experiment was programmed using the z-Tree software (Fischbacher 2007). A total of 150 subjects took part in the experiment, 80 in the Flat and 70 in the Contingent treatment.Footnote 16 When entering the laboratory, participants were randomly assigned to a cubicle and were provided with printed instructions (see Appendix 1).

Participants were given some minutes to go through the instructions privately. Then, a member of the staff read them aloud and answered questions. Before participants were assigned to their roles, they had to answer some control questions, checking their comprehension of the instructions. Only after everybody had answered these questions correctly did the actual experiment start.

We set the exchange rate at 0.4 euro for 100 tokens (1 token = 0.004 euros). Participants were paid cumulatively over the 30 rounds of the experiment. They received a fixed amount of 3 euros for having shown up. The experiment lasted between 45 min and 1 h. On average, participants earned a total of 15.35 euros.

After condition Human, all participants had to fill in a short questionnaire to access the second part of the experiment (see Appendix 2, also for results). Subjects reported their degree of agreement to some statements on a 5-point Likert scale. For TPs, we had three items investigating their motivation to comply (if for themselves, for the group, or to avoid sanctions). Moreover, four other items were dedicated to an evaluation of the behavior of TAs. Concerning TAs, we had three items asking them to evaluate their own behavior and an additional item asking how they thought others would have acted in their role. At the end of the experiment, TPs had to fill in a questionnaire similar to the previous one (see, again, Appendix 2).

4 Results

In this section, we, first, look at inspections and tax compliance following the hypotheses spelled out in Sect. 3.3. Then, we investigate potential spillover effects of inspections on compliance to answer the main research question of our paper. We, finally, perform an exploratory analysis of different types of audit strategies adopted by TAs.

4.1 Inspections

As a first step, we need to understand TAs’ behavior in the Human treatment, as this builds the stepping stone to understand TPs’ behavior, in which we are ultimately interested. TAs could influence the game by self-reporting the value from the die roll in each of the first 20 rounds, thus determining the occurrence of inspections. We have a total of 30 TAs, 14 in the condition Contingent and 16 in condition Flat.

In Fig. 1, we provide a representation of the distribution of the total number of inspections performed by each TAs (bars) together with the theoretical density distribution obtained from a binomial distribution with 20 random draws and a probability of success of 1/6 (solid line). The vertical dashed line captures the mean of the empirically observed distribution.

Binomial probability distribution vs actual frequency distribution. Note: The bars in the two graphs depict the relative frequency distribution of the total number of inspections carried out by TAs in condition Human for incentive condition Contingent in the top part (14 observations) and Flat in the bottom part (16 observations); the dashed vertical lines show their mean. As a comparison, the solid lines connecting the circles in the two graphs represent the same theoretical density distribution of inspections generated, taking 20 random draws from a binomial distribution with a success probability of 1/6

The overall frequency of inspections is equal to 32.8% and 31.1% in conditions Flat and Contingent, respectively. A binomial test shows that both frequencies are significantly different from the expected frequency of 16.7% (exact binomial test, for both p < 0.001). This means that, in line with Hypothesis 1a, TAs in Contingent tend to over-inspect TPs. However, in contrast to Hypothesis 1a, Fig. 1 highlights a strong similarity in behavior across treatments. The average number of inspections is equal to 6.2 and 6.6 in conditions Contingent and Flat, respectively. Non-parametric tests show that the two distributions do not statistically differ from each other (Wilcoxon rank sum test, \(p = 0.883\); Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, \(p = 1.000\)).

Result 1

Inspections are more frequent than predicted by the roll of the die, both in condition Contingent and Flat. There is no significant difference in inspection frequencies across conditions Contingent and Flat.

The questionnaire provides us with some more insights into TAs’ self-reported motivations that might help explain these results (see Appendix 2). The motivation that attracts the highest level of agreement is “I acted to enforce the rules”, with an average agreement score of 4.4. Most TAs disagree on the fact that they acted in their own personal interest. Finally, the interest of the group seems not to be a strong motivation driver, and most of the TAs believe that others in the same role would have behaved as they did. Overall, TAs’ answers do not significantly differ in Contingent and Flat (Wilcoxon rank sum tests, all \(p>\) 0.200). Furthermore, answers in the questionnaire are not correlated to the number of inspections implemented (Spearman’s rank correlation \(\rho\), all \(p>\) 0.161).

4.2 Tax compliance

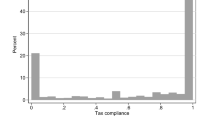

Figure 2 provides a representation of the distribution of taxes paid in the 30 rounds of the experiment. In addition to the conventional pieces of information provided by the boxplots, the diamond dots capture mean values in each round. The dashed horizontal line shows the average value for each of the four experimental conditions separately.

Taxes paid by the TPs. Note: We present boxplots on tax payments for each round. Incentive condition Contigent is shown in the top block and Flat in the bottom one. Diamonds represent each round’s average. The dashed horizontal line depicts average tax payments for condition Human and Machine for each of the two incentive conditions

Considering inspection condition Human first, the average taxes paid are equal to 18.3 and 17.9 in conditions Contingent and Flat, respectively. To gather a measure of the heterogeneity of contributions within the groups, we computed the distribution of the standard deviations of taxes paid within each group in a given taxation round. The average values of the distribution are rather large and equal to 9.898 and to 9.091 in conditions Contingent and Flat, respectively.Footnote 17

As shown by the boxplots, the central tendency of the distribution is larger than the full evasion prediction obtained under the assumption of risk neutrality and inspections faithfully determined by the outcome of the die. Furthermore, taxes paid are quite stable throughout the 20 rounds of condition Human. Spearman’s rank correlation tests do not show any significant correlation between taxes paid at the group level and round number, neither in Contingent (\(\rho = -0.033\) , \(p = 0.588\) ) nor in Flat (\(\rho = -0.085\) , \(p = 0.131\) ). Furthermore, taxes paid in the two incentive regimes of the Human treatment do not statistically differ (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, \(p = 0.984\) ). This is a straightforward consequence of what we reported in Result 1 and goes partly against Hypothesis 1b.

Result 2

In condition Human, taxes collected are high, quite stable over rounds, and do not differ across condition Contingent and Flat.

The analysis reported in Appendix 3 shows a positive correlation between the number of inspections and tax compliance. Indeed, questionnaire data (see Appendix 2) reveal that the main motivation to pay taxes in condition Human is one’s own personal interest, driven by the urge to avoid sanctions. Most of the TPs disagree on the fact that the TA followed her personal interest or the group’s interest. The majority of TPs moderately agree on the fact that the TA followed the rules in a transparent way. The amount of taxes paid in Human is positively and significantly correlated to the belief that the tax agent acted in the group’s interest (Spearman’s rank correlation \(\rho\) = 0.194, p = 0.034). There is also a positive correlation between taxes paid and agreement about the payment of taxes in the group’s interest (\(\rho\) = 0.372, \(p<\) 0.001) and to avoid sanctions (\(\rho\) = 0.245, p = 0.007). The same pattern emerges also in condition Machine (\(\rho\) = 0.234, \(p<\) 0.010, and \(\rho\) = 0.229, \(p<\) 0.012). All other correlations between answers in the questionnaire and total taxes paid are not statistically significant (all \(p>\) 0.154).

Concerning taxes collected in condition Machine, we find that both for condition Contingent and Flat average compliance stays well above the full evasion benchmark predicted in Hypothesis 2 (18 and 15.5). The average standard deviation of taxes paid within groups is equal to 10.747 in Contingent and to 10.255 in Flat. These values are larger than those observed in condition Human. While there is no significant difference in taxes paid between the two incentive conditions (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, p = 0.334), we register a drop in taxes paid in incentive condition Flat between condition Machine and Human. This drop between Flat/Human and Flat/Machine is moderate (2.4 points), but statistically significant (Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, p = 0.003). There is no significant difference between Contingent/Human and Contingent/Machine (p = 0.808).

Result 3

In condition Machine, taxes collected are high and quite stable. No significant differences can be observed between condition Contingent and Flat.

To provide further support for our results, we perform a regression analysis on the taxes paid by TPs. The dependent variable Taxes Paid is regressed against a set of explanatory variables: Contingent is equal to 1 in incentive condition Contingent and equal to 0 in Flat; Period captures the round in which taxes are paid and spans the range 1–20 in Human and 1–10 in Machine; Machine is equal to 1 in condition Machine and to 0 in Human. Table 2 presents the estimation outcomes of a linear mixed model with clustered random effects at the individual and group level.

As shown by estimates in Table 2, taxes paid are positive and stable over rounds, though slightly declining in Human. We confirm that there is no significant difference between incentive conditions, as the coefficient of Contigent shows. The positive interaction term Contingent:Machine points to a significant difference between the Human condition in incentive condition Flat and the Machine condition in incentive condition Contingent. However, a linear hypothesis test (Contingent + Contingent:Machine = 0, Chi-square test, p = 0.206) shows no difference between Contingent and Flat in Machine. Furthermore, no significant drop in taxes paid between Human and Machine is observed, neither in condition Contingent (see coefficient of Machine) nor in condition Flat (Machine + Contingent:Machine = 0, Chi-square test, p = 0.491). In addition, estimated parameters show that the drop in contributions observed in Machine for incentive condition Flat is not statistically significant. These findings confirm the results on compliance reported above.

After having established that taxes paid in both the Human and the Machine condition are high, quite stable and that high tax compliance persists even when inspection rates are lowered below the deterrence threshold, we provide here an assessment of the impact of controls in Human on compliance in Machine (spillover effects). We identify a strong positive correlation (Spearman’s rank correlation \(\rho\)) between total number of controls in a group in Human and total taxes paid in Machine, both in Contingent (\(\rho = 0.560\), \(p = 0.037\)) and in Flat (\(\rho = 0.515\), \(p = 0.041\)). The presence of positive spillover effects is also corroborated by Table 3, reporting the fit of a linear mixed model with random effects at the individual and group levels. The dependent variable is given by taxes paid by an individual in a given period. The spillover effect is captured by the explanatory variable Inspections(cum).H, which counts the number of inspections performed by the TA. We also control for incentive schemes (Contingent vs. Flat) and for the Period of tax collection.

As the estimated coefficient of Inspections(cum).H shows, more inspections performed by a TA determine higher compliance levels in the Machine condition when inspections are fully random and non-deterrent. No significant difference between the two incentive schemes is registered.

Result 4

More inspections performed by the TAs in Human result in higher compliance in condition Machine.

4.3 Types of audit strategies

We complement our main results with an exploratory analysis of the inspection strategies employed by the TAs. TAs implement very different inspection strategies, which in turn lead to different compliance levels on the TPs’ side. To gain insight into this, we categorize TAs according to the total number of inspections performed in condition Human and the average compliance reached therein (see Appendix 3, where we display group compliance patterns together with audit strategies). A hierarchical cluster analysis leads to the isolation of three major groups,Footnote 18 as displayed in Figure 3. We label the three groups in the following way: Honests (triangles), Beaters (squares), and Educators (circles).

Categorization of audit strategies by TAs. Note: The graph depicts TAs as points on the graph displaying the relationship between the total number of inspection implemented during condition Human and the average taxes collected within that period. A hierarchical cluster analysis provides a categorization of TAs in three distinct types: Beaters (squares), Educators (circles) and Honests (triangles)

Beaters perform a large number of inspections and the TPs to whom they are associated display high levels of tax compliance. Educators perform fewer inspections, but achieve high tax compliance as well employing particular audit strategies (see Appendix 3). Honests implement the lowest number of inspections and register the lowest level of compliance. Non-parametric tests show that Beaters perform significantly more inspections than Educators and Honests (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.008 and p = 0.010, respectively). At the same time, Educators inspect more often than Honests (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p < 0.001). The frequency of inspection of the latter does not significantly differ from the truthful frequency of 1/6 (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.115).

Concerning the effects on tax compliance, Educators and Beaters reach significantly higher levels compared to the Honests (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, p < 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively). In contrast, no significant difference in taxes collected is registered when comparing Educators and Beaters (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, p = 0.421).

Result 5

Three alternative styles of inspection strategies can be identified: Honests, Beaters, and Educators. Honests perform inspections in line with the preset inspection rule but obtain low compliance. The other two obtain high compliance. However, Educators perform significantly less inspection than Beaters.

5 Discussion

Assigning real participants to the role of TA and leaving them some discretion led to more inspections than prescribed by the preset rule (Result 1). This is only partially in line with our predictions, as the behavior of TAs did not differ across incentive conditions Flat and Contingent (Result 1). We conjecture that TAs might have had other, non-monetary, interests in reaching and keeping a norm of high compliance among their TPs. Questionnaire results support this: TAs state to be guided by the intention to enforce the rules in their audit strategies. Thus, some TAs seem to have interpreted their role more broadly and to have been motivated to increase tax compliance regardless of their monetary incentives. It is important to note here that high compliance comes at a monetary benefit for TPs and, hence, TAs’ lies were “efficient”. Indeed, research on lying shows that people lie more when their lies benefit others (Erat and Gneezy 2012; Gino et al. 2013). This motive seems to outweigh the monetary incentives and level the predicted difference in behavior in our setting.Footnote 19 Our findings also resonate with the vast literature on third party punishment showing that people are willing to intervene to sustain fairness norms even at a cost for themselves and despite not being the victim of norm violation (see, e.g., Fehr and Fischbacher 2004). In sum, this suggests that the main driver of TAs’ behavior were not their monetary incentives but a desire to contrast evasion in their group and that this led them to behave similarly across both incentive conditions.

Moving to the main focus of this paper, we find that in condition Human, i.e., when TAs determine the occurrence of audits, taxes paid are high, quite stable over rounds, and not influenced by the incentive condition TPs were in (Result 2). This establishes a positive effect of aggressive audit strategies on tax compliance while these policies are still in place in our experiment. We also find that compliance in condition Machine stays well above the predicted level of zero and does not differ across incentive conditions (Results 3). We show that these results are caused by the intensity with which TAs inspect TPs in their group and provide direct causal evidence for a positive spillover effect between inspections in condition Human and compliance in condition Machine (Result 4).

Our findings point to the fact that TPs internalized (knowingly or not) the high compliance norm, if subject to its enforcement, and stuck to the virtuous high compliance equilibrium. This finding is at odds with results on the effect of peer punishment on cooperation, where subjects start misbehaving as soon as such opportunities are taken away (Fehr and Gachter 2000). Dai et al. (2017) report a similar finding in a “daily public transportation game”, in which participants are exposed to intense audits and have to decide whether or not to buy a ticket. However, in their setting, audits are exogenously imposed, while in our case, it is a human TA who makes this decision. This endogenous element can provide a signal that a high compliance norm is desirable and hence be more effective once audits become less frequent. Our results are also in line with recent findings by Galbiati et al. (2018), who show that fines can positively influence cooperation even when no longer in place due to reciprocal preferences. In our setting, this result could be explained by a preference for perfect conditional cooperation (Fischbacher et al. 2001) induced in the first phase of the experiment. This points to the fact that the public good component in our experiment might be crucial to sustaining compliance in the long run. Groups of TPs that were led to high compliance seem to have recognized its benefits and continued to comply. In sum, TAs in our experiment seem to have established a norm of high compliance, which outlived their possibility of intervening.

Finally, our analysis of types shows that TAs reached this high compliance norm with widely different strategies. While adhering to the preset rule did not benefit Honests, bluntly ignoring it obviously led to higher compliance for Beaters in the Human and even in condition Machine. In comparison to the Beaters, Educators obtained similar levels of compliance by adopting much fewer inspections. By departing less evidently from the rule, they manage to educate their TPs to the high compliance norm without beating them too hard. These differences in audit patterns are particularly relevant in the evaluation of results reached by Educators and Beaters since Educators adopt a more efficient strategy for two reasons, a direct and an indirect one. First, by implementing fewer inspections, their strategy is clearly more cost-effective. Indeed, if one were to introduce a cost of the inspection, Educators would arguably fare better than Beaters in a cost-benefit comparison. Second, more subtle deviations from the preset rule might positively influence how TPs perceive the use of TAs’ power. In turn, this can lead to more compliant behavior in general, especially in areas where the use of raw power by tax authorities is more difficult.

6 Conclusion

We present an innovative design that allows us to test the effect of aggressive audit policies on tax compliance. We find that participants in the role of the tax authority bend the rules to reach high compliance, even if they have no direct interest in the level of taxes paid. This behavior puts participants in the role of taxpayers under pressure and leads to higher tax compliance. Once a norm of high compliance is reached, it is carried over even when fines are non-deterrent. Our results provide evidence in favor of a positive effect of aggressive audit strategies both when these policies are in place and after they end. Taxpayers reach a high compliance equilibrium and stick to it even when not forced to do so. Our study also provides an original methodological contribution, which offers new ways to investigate how the relationship between tax authorities and taxpayers influences compliance in a controlled setting.

Using experiments to study real-life phenomena like tax compliance, which involve policy interventions, can paint only a partial picture. While our results suggest that these policies can constitute an effective instrument in the toolbox of tax authorities, our experiment abstracts away from some features that are relevant in the real world. For example, to evaluate the overall welfare effects of aggressive audit strategies, one should also consider the costs of audits (both direct costs and opportunity costs). Another important consideration is that these policies could crowd out decentralized norm enforcement by the taxpayers themselves (Kube and Traxler 2011) and could also have spillovers in other domains. Similarly, frequent inspections could signal to law-abiding taxpayers that others are evading and, as a consequence, they might start evading as well. Finally, self-selection of more selfish individuals into jobs where income is self-reported could potentially alter some of our results. To sum up, while a great advantage of lab experiments is that they can establish clear causality relationships and open the way to controlled manipulations in the field, the evidence provided in this paper has to be complemented with further empirical data and validated with different methods. Evidence presented here may encourage this venture.

Notes

As an example, this is routinely done by the Italian tax authority. Some recent cases involve dentists (Trentino 2014), Bed & Breakfasts (Studio Legale Leone-Fell 2018), or boutiques in the famous winter destination of Cortina D’Ampezzo (Il Fatto Quotidiano 2012). In the US, the IRS has also been targeting its audits, e.g., on small businesses (William 2019). Another prominent case in the US saw allegations that the Obama administration was targeting certain political groups via the IRS (CNN Library 2018).

This resentment is exemplified by the many websites and articles dedicated to help the targets to fight back (Harrison 2013).

As discussed in the description of our experimental design, we focus on income taxes following the tradition of most lab experiments (Alm 2012). We thereby leave out cases in which taxpayers are forced to report their income, which restricts our analysis to a subset of taxpayers.

Muehlbacher and Kirchler (2016) review the methodological debate on the experimental approach to tax compliance, focusing on its external validity.

This drop might be due to a misconception of probabilities leading experimental taxpayers to evade more just after they have been detected, Another explanation is that subjects evade more to recover the losses due to fines. Kastlunger et al. (2009) found that a possible way to remove the bomb crater effect is to perform two sequential inspections.

A further reason why we implement endogenous inspections is that, as Baldry (1986) points out, the decision whether to evade or not taxes should not be reduced to a gambling decision. Recent work has introduced endogenous audit schemes in a tax evasion experiment (see, e.g., Vossler and Gilpatric 2017). However, inspections were still managed by the computer and not by a human.

Clearly, tax authorities do not inspect (only) based on random draws. However, once the pool of potential evaders has been narrowed down using risk profiles and other techniques, audits can be seen as nearly random events ceteris paribus.

The experiment was framed. See Appendix 1 for instructions.

This procedure is equivalent to declaring an income and paying a tax according to a given tax rate. Since the ultimate aim of evading taxes is paying lower taxes and not declaring a lower income, we undertook this simplification in our experimental procedures.

TPs also had to roll a die and report the outcome. Although the outcome reported by TPs had no influence on the game, we decided to let them roll their die to create a fully private condition for tax agents. To this end, each cubicle was made soundproof with a bubble-wrap layer.

TAs were asked to estimate the total contribution of TPs in their group in each round during condition Machine.

The TA’s earnings are independent of the fines as this would create redundancy in her payoff function.

This amount was chosen to avoid any ex-ante inequality concerns.

Note that the inspection equilibrium is also weakly payoff dominant with respect to all mixed strategy equilibria.

We perform a hierarchical cluster analysis with complete linkage using Euclidean distances based on two dimensions: total number of inspections performed by the TA in condition Human and the average compliance level reached by her group in the same condition. Using a divisive approach, this analysis leads to the identification of 3 main clusters, since for any further splits gains are negligible.

Note that our predictions in condition Flat are based on the assumption of a weak preference for truth-telling. If TAs also derive utility from upholding a norm of compliance, this could outweigh small lying costs and lead TAs to misreport the outcome of the die roll.

References

Abeler J, Nosenzo D, Raymond C (2019) Preferences for truth-telling. Econometrica 87(4):1115–1153

Allingham MG, Sandmo A (1972) Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. J Public Econ 1(3–4):323–338

Alm J (1991) A perspective on the experimental analysis of taxpayer reporting. Account Rev 66(3):577–593

Alm J (2012) Measuring, explaining, and controlling tax evasion: lessons from theory, experiments, and field studies. Int Tax Public Finance 19(1):54–77

Alm J, Jacobson S (2007) Using laboratory experiments in public economics. Natl Tax J 60:129–152

Alm J, McClelland GH, Schulze WD (1992) Why do people pay taxes? J Public Econ 48(1):21–38

Alm J, McClelland GH, Schulze WD (1999) Changing the social norm of tax compliance by voting. Kyklos 52(2):141–171

Baldry JC (1986) Tax evasion is not a gamble: a report on two experiments. Econ Lett 22(4):333–335

Cason TN, Friesen L, Gangadharan L (2016) Regulatory performance of audit tournaments and compliance observability. Eur Econ Rev 85:288–306

Clark J, Friesen L, Muller A (2004) The good, the bad, and the regulator: an experimental test of two conditional audit schemes. Econ Inquiry 42(1):69–87

Dai Z, Galeotti F, Villeval MC (2017) The efficiency of crackdowns: a lab-in-the-field experiment in public transportations. Theory Decis 82(2):249–271

Di Tella R, Schargrodsky E (2003) The role of wages and auditing during a crackdown on corruption in the city of Buenos Aires. J Law Econ 46(1):269–292

Eeckhout J, Persico N, Todd PE (2010) A theory of optimal random crackdowns. Am Econ Rev 100(3):1104–35

Ellingsen T, Johannesson M (2004) Promises, threats and fairness. Econ J 114(495):397–420

Engelmann D, Strobel M (2004) Inequality aversion, efficiency and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments. Am Econ Rev 94(4):857–869

Erat S, Gneezy U (2012) White lies. Manag Sci 58(4):723–733

Fehr E, Fischbacher U (2004) Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol Hum Behav 25(2):63–87

Fehr E, Gachter S (2000) Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev 90(4):980–994

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Q J Econ 114(3):817–868

Fellner G, Sausgruber R, Traxler C (2013) Testing enforcement strategies in the field: threat, moral appeal and social information. J Eur Econ Assoc 11(3):634–660

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Fischbacher U, Föllmi-Heusi F (2013) Lies in disguise—an experimental study on cheating. J Eur Econ Assoc 11(3):525–547

Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Fehr E (2001) Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ Lett 71:397–404

Fortin B, Lacroix G, Villeval M-C (2007) Tax evasion and social interactions. J Public Econ 91(11):2089–2112

Friedland N, Maital S, Rutenberg A (1978) A simulation study of income tax evasion. J Public Econ 10(1):107–116

Galbiati R, Henry E, Jacquemet N (2018) Dynamic effects of enforcement on cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(49):12425–12428

Gërxhani K, Schram A (2006) Tax evasion and income source: a comparative experimental study. J Econ Psychol 27(3):402–422

Gino F, Ayal S, Ariely D (2013) Self-serving altruism? The lure of unethical actions that benefit others. J Econ Behav Organ 93:285–292

Guala F (2005) The methodology of experimental economics. Chapter 3. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hallsworth M, List JA, Metcalfe RD, Vlaev I (2017) The behavioralist as tax collector: Using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. J Public Econ 148:14–31

Kartik N (2009) Strategic communication with lying costs. Rev Econ Stud 76(4):1359–1395

Kastlunger B, Kirchler E, Mittone L, Pitters J (2009) Sequences of audits, tax compliance, and taxpaying strategies. J Econ Psychol 30(3):405–418

Kirchler E, Muehlbacher S, Kastlunger B, Wahl I (2007) Why pay taxes? A review of tax compliance decisions. Int Stud Program Work Pap 7:30

Kleiman MA (2009) When brute force fails: How to have less crime and less punishment. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Kube S, Traxler C (2011) The interaction of legal and social norm enforcement. J Public Econ Theory 13(5):639–660

Mittone L (1997) Subjective versus objective probability: results from seven experiments on fiscal evasion

Mittone L (2006) Dynamic behaviour in tax evasion: an experimental approach. J Socio-Econ 35(35):813–835

Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E (2016) Taxperiments: about the external validity of laboratory experiments in tax compliance research. Die Betriebswirtschaft 76(1):7–19

Sherman LW (1990) Police crackdowns: Initial and residual deterrence. Crime and Justice 12:1–48

Slemrod J, Weber C (2012) Evidence of the invisible: toward a credibility revolution in the empirical analysis of tax evasion and the informal economy. Int Tax Public Finance 19(1):25–53

Srinivasan TN (1973) Tax evasion: a model. J Public Econ 2(4):339–346

Vossler CA, Gilpatric SM (2017) Endogenous tax audits and taxpayer assistance services: theory and experiments. Technical report

Webley P (1991) Tax evasion: an experimental approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Yitzhaki S (1974) Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. J Public Econ 3(2):201–202

CNN Library (2018) IRS scandal fast facts. [online]. https://edition.cnn.com/2014/07/18/politics/irs-scandal-fast-facts/index.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2019

Harrison J (2013) IRS auditors targeting small business owners — but there are ways to protect your company. The Washington Post. [online]. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/on-small-business/post/irs-auditors-targeting-small-business-owners--but-there-are-ways-to-protect-your-company/2013/04/16/32ac68aa-a697-11e2-8302-3c7e0ea97057_blog.html?noredirect=on. Accessed 30 Aug 2019

Il Fatto Quotidiano (2012) Controlli fiscali a Cortina Blitz di 80 agenti per stanare gli evasori. [online]. https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2012/01/03/controlli-fiscali-cortina-blitz-agenti-stanare-evasori/181286/. Accessed 30 Aug 2019

Studio Legale Leone-Fell & Associati (2018) B&B e case vacanze, controlli a tappeto: cosa fare in caso di verifica fiscale. [online. https://www.avvocatoleone.com/bb-e-case-vacanze-controlli-a-tappeto-cosa-fare-in-caso-di-verifica-fiscale/. Accessed 30 Aug 2019

Trentino (2014) I dentisti nel mirino della Guardia di Finanza. [online]. http://www.giornaletrentino.it/cronaca/trento/i-dentisti-nel-mirino-della-guardia-di-finanza-1.990110. Accessed 30 Aug 2019

William D (2019) Is the irs targeting small businesses? Yep, says one expert. Small business trends. [online] https://smallbiztrends.com/2016/09/irs-targeting-small-businesses.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2019

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthias Kasper, Erich Kirchler, Christoph Kogler, Jerome Olsen, two anonymous reviewers, and the associate editor for their helpful comments and support. We are indebted to audiences of seminars at the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, as well as attendees of the 5th edition of “The Shadow Economy, Tax Evasion and Informal Labor" conference and the 5th "International Meeting on Experimental and Behavioral Social Sciences”. Eugenio Verrina acknowledges financial support from the Max Planck Society and the French National Research Agency (ANR, DECISION project, ANR-19-CE26-0019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Instructions

Here we report the instructions given to participants at the experiment translated from Italian. We insert only one version and specify which parts were different according to the incentive condition. Of course participants received different instructions for condition Flat and Contigent.

General instructions

Welcome,

You are about to take part in an experiment on economic decision-making. For having shown up on time, you will receive 3 Euros at the end of the experiment. If you have any doubt during the experiment, please address a lab assistant by raising your hand. In case you use the computer for activities not strictly tied to the experiment, you will be excluded from taking part in the experiment and from any payment.

Hereunder, you will find the instructions regarding the exact proceeding of the experiment. Please read the instructions carefully. Before the experiment starts, you will have to answer some questions to verify your comprehension of the instructions.

Instructions

The experiment is consists of a total of 30 rounds and is divided into two phases. Phase 1 consists of 20 rounds and Phase 2 consists of 10 rounds. Participants will be randomly assigned to the role of tax payer or to the role of tax agent. Participants assigned to the role of tax payer will be divided into groups of four participants each. The composition of these groups will be the same for all 30 rounds. The identity of the other group members will not be revealed to any participant. A single participant with the role of tax agent will be assigned to each of these groups and will remain the same for all 30 rounds. The identity of the tax agent will not be revealed to any participant; likewise, the tax agent will not know the identity of any other participant. There will, thus, be 4 distinct groups, each made up of 4 taxpayers and 1 tax agent. Groups will never interact with each other. During the experiment, participants will use experimental currency tokens, which will be converted in Euros at the end of the experiment at an exchange rate of 100 tokens = 0.40 Euros.

Phase 1

Tax payer

At the beginning of each round, taxpayers will receive 100 tokens and will decide how much to pay in taxes. The tax rate is set at 30%; on an amount of 100 tokens, taxes due are, thus, 30 tokens. Each tax payer will freely choose the number of tokens he or she wants to pay, between 0 and 30 tokens. Inside each group, taxes will be gathered in a unique account, the total amount will be multiplied by a factor of 1.5. The total amount of tokens obtained this way will be divided into equal parts among all four taxpayers belonging to the same group, independently of the contribution of each single tax payer.

EXAMPLE:

Tax payer T1 pays 20 tokens in taxes, T2 10 tokens, T3 30 tokens, and T4 0 tokens. The total amount \(20+10+30+0=60\) is multiplied by 1.5; thus, \(60*1.5=90\); and divided in equal parts among each tax payer, hence 90/4=22.5. Each tax payer will receive 22.5 tokens, which will be added to those he or she still owns. In the example, T1 will receive \(80+22.5=102.5\), T2 \(90+22.5=112.5\), T3 \(70+22.5= 92.5\), and T4 \(100+22.5=122.5\).

Tax agent

Each tax agent is in charge of carrying out the auditing process of taxpayers inside his or her group. In case an inspection takes place, each tax payer of the group who has not paid the entire amount due will be fined. The fine is composed of the rest of the tax due multiplied by 2.

Flat: “The payment of the tax agent is fixed and independent from the proceeding of the experiment. The exact amount of the payment will be revealed only at the end of the experiment.”

Contingent: “The payment of the tax agent in each round is equal to the total taxes paid in his or her group multiplied by 1.5.

EXAMPLE:

The total amount of taxes paid by the taxpayers, \(20+10+30+0=60\), is multiplied by 1.5, hence \(60*1.5=90\). The tax agent has earned 90 tokens in this round.”

Die roll

During each round, participants will be asked to roll privately a die inside their cubicle on the bubble wrap layer a single time and report the outcome via the computer interface.

The outcome reported by taxpayers will have no consequence on the experiment.

The outcome reported by the tax agents, on the contrary, will determine the implementation of the fiscal inspection. The inspection will take place each time the tax agent declares via the computer interface that the outcome of his or her die roll is equal to 3. The probability of obtaining this result is 1/6 (16.67%). When the number 3 is reported and the inspections takes place, all taxpayers of the same group are audited.

EXAMPLE:

If the result reported by the tax agent was equal to 3, an inspection would take place. T1 would be fined for 20 tokens, T2 for 40, T3 for 0, and T4 for 60. The fines would diminish the total earnings in that round. T1 would remain with 82.5, T2 with 72.5, T3 with 92.5, and T4 with 62.5.

At the end of each round, each tax payer will get to know his or her earnings in that round and be told whether an inspection took place. Each tax agent will get to know the taxes paid inside his or her group (Contingent: and the total amount earned in that round).

Phase 2

Tax payer

In each round taxpayers will decide how much to pay in taxes, but they will not roll the die anymore. Otherwise, the experiment will carry on as in Phase 1.

Tax agent

In this phase tax agents will not be in charge of carrying out the fiscal inspection by rolling the die. Tax agents will only be asked to estimate the total amount of taxes paid by taxpayers in their group in each round. The inspection will be carried out by a computerized random mechanism that assigns the probability of 1/6 (16.67%) for an inspection in each round. The tax agents will still receive information about the total of taxes paid in their group and the taking place of an inspection.

Contingent: “Their earning will be determined, as in Phase 1, by the total of tax paid multiplied by 1.5.”

Final payment

Contingent: “The payment will be determined for all participants in a cumulative way, by summing up the earnings in all 30 rounds that compose the experiment.”

Flat: “The payment will be determined for taxpayers in a cumulative way, by summing up the earnings in all 30 rounds that compose the experiment.

The payment of tax agents is equal for all and independent of the proceeding of the experiment. The exact amount will be revealed at the end of the experiment.”

The final payment will occur in Euros at the end of the experiment. The exchange rate is set at 40 Cents every 100 tokens (100 tokens = 0.4 Euros).

Questionnaires

Here we report the questionnaires participants filled in after condition Human (Questionnaire 1) and condition Machine (Questionnaire 2) alongside with the mean, median, and standard deviation for each of the items. The original text is translated from Italian. Answers were collected on a 5-point Likert scale, from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”.

Questionnaire 1

-

Taxpayers

-

When I paid my taxes I did it in the group’s interest. (mean = 2.9, median = 3.0, s.d. = 1.29)

-

When I paid my taxes I did it in my personal interest. (mean = 3.91, median = 4.0, s.d. = 1.08)

-

When I paid my taxes I did it to avoid sanctions. (mean = 3.63, median = 4.0, s.d. = 1.23)

-

I think the tax agent followed the rules in a transparent way. (mean = 3.34, median = 3.5, s.d. = 1.48)

-

I think the tax agent acted in his own interest. (mean = 2.68, median = 2.5, s.d. = 1.4)

-

I think the tax agent acted in the group’s interest. (mean = 2.17, median = 2.0, s.d. = 1.13)

-

If I had been the tax agent, I would have acted the same way he or she did. (mean = 3.16, median = 3.0, s.d. = 1.51)

-

-

Tax agents

-

I acted in the interest of the whole group. (mean = 2.87, median=3.0, s.d.=1.33)

-

I acted in my personal interest. (mean = 2.23, median = 1.5, s.d. = 1.50)

-

I acted to enforce the rules. (mean = 4.4, median = 5.0, s.d. = 0.97)

-

I think another participant in my role would have acted the same way I did. (mean = 3.8, median = 4.0, s.d. = 1.21)

-

Questionnaire 2

-

Tax payers

-

When I paid my taxes I did it in the group’s interest. (mean = 2.85, median = 3.0, s.d. = 1.29)

-

When I paid my taxes I did it in my personal interest. (mean = 3.98, median = 4.0, s.d. = 1.03)

-

When I paid my taxes I did it to avoid sanctions. (mean=3.6, median = 4.0, s.d. = 1.15)

-

Since the tax agent was replaced by a random device, I behaved in a different way. (mean = 2.98, median = 3.0, s.d. = 1.51)

-

Inspections and tax compliance

We present here an analysis of the relationship between inspections and tax compliance. In particular, we check whether a higher number of inspections is associated with more taxes paid in condition Human. Figure 4 displays the correlation between the number of inspections performed by a TA and taxes paid by its group of TPs.

Taxes paid and controls in condition Human. Note: The x-axis captures the number of inspections performed by a TA, and the y-axis shows the total taxes paid by the group matched with the TA. The dashed line provides a representation of a linear fit of the data. The Contingent and the Flat payoff conditions are shown in the upper panel and lower panel, respectively

As the graph shows, there is a positive correlation between the number of inspections and taxes paid. Specifically, in Contingent the Spearman’s rank correlation rho is equal to 0.491 (\(p = 0.075\)) and in Flat it is equal to 0.588 (\(p = 0.017\)). Thus, our data show that higher compliance is associated with more inspections in Human.

Compliance patterns

We here report audit and compliance patterns of all groups in the experiment. As can be easily seen, Beaters audit their TPs nearly in each period. Honests seem to be truthfully reporting the outcome of the die, since they perform very few and scattered audits. Educators implement more sophisticated audit schemes, e.g., they concentrate many audits in the starting periods producing an echo effect (Guala 2005; Mittone 2006) or implement repeated audits if they see compliance going down.

Concerning TPs, the graphs show that just a few of them adopt the same strategy throughout the experiment. The most persistent types seem to be those choosing full compliance or full evasion. Most TPs tend to change their contribution plan over time, and this contributes to the heterogeneity observed at the group level. However, no systematic connection between TAs strategies and heterogeneity in behavior can be identified from a visual inspection.

Audit and compliance patterns Note: Each box represents a group of 4 TPs and 1 TA. The TA’s type and the ID of the group are reported in the stripes on top of the graph. Rounds are listed on the x-axis, while taxes paid are displayed on the y-axis. Different dot types capture taxes paid by each group member, while solid lines capture average taxes paid in the group. The vertical dotted lines represent rounds in which an inspection took place. Human and Machine conditions are divided by a vertical solid line. The dashed horizontal lines show average overall contributions

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mittone, L., Ploner, M. & Verrina, E. When the state does not play dice: aggressive audit strategies foster tax compliance. Soc Choice Welf 57, 591–615 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01325-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01325-y