Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the research performance in ophthalmology in Germany based on the findings of the recent research map of the German Ophthalmological Society (DOG) and to suggest strategies for future improvements on a national level both to DOG as well as to politics. The focus is on preclinical and translational clinical research.

Methods

International expert panel evaluation and discussion organized by the Task Force Research of the German Ophthalmological Society (DOG).

Results

The international view on the German ophthalmological research landscape was generally positive. The value for money relationship was judged as very good. As Germany is facing an aging society and vision impairment will create an ever-increasing socioeconomic burden, the reviewers suggested several lines of future activities: an increased activity of securing intellectual property, more lay audience lobbying, intensified collaboration and critical mass building between “lighthouses” of ophthalmic research in Germany, as well as the establishment of a German national eye institute equivalent.

Conclusion

The ophthalmological research performance in Germany was rated to be very good by an international expert panel. Nonetheless significant improvements were requested in the fields of translation (clinical trials, IP), synergy between specialized institutions and governmental funding for a German center for eye research.

Zusammenfassung

Ziel

Die Forschungsleistung in der Augenheilkunde in Deutschland auf der Grundlage der Ergebnisse der aktuellen DOG-Analyse (Forschungslandkarte der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft [DOG]) zu bewerten und der DOG sowie der Politik Strategien für zukünftige Verbesserungen auf nationaler Ebene vorzuschlagen. Der Fokus liegt dabei auf der präklinischen und translationalen, klinischen Forschung.

Methoden

Internationale Expertenpanelauswertung und Diskussion, organisiert von dem Arbeitskreis Forschung der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft (DOG).

Ergebnisse

Die deutsche Forschungslandschaft in der Ophthalmologie ist international gut anerkannt. Das Preis-Leistungs-Verhältnis wurde als sehr gut bewertet. Da Deutschland mit einer alternden Gesellschaft konfrontiert ist und Sehbehinderungen eine immer größere sozioökonomische Belastung darstellen werden, schlugen die Gutachter mehrere Ziele für zukünftige Aktivitäten vor: eine verstärkte Aktivität zur Sicherung des geistigen Eigentums, mehr Lobbyarbeit mit Patientenvertretern, eine intensivere nationale Zusammenarbeit und der Aufbau einer kritischen Masse zwischen den „Leuchttürmen“ der ophthalmologischen Forschung in Deutschland sowie die Einrichtung eines „Deutschen National Eye Institutes“.

Schlussfolgerung

Die ophthalmologische Forschungsleistung in Deutschland wurde von einem internationalen Expertengremium als sehr gut bewertet. Dennoch wurden deutliche Verbesserungen in den Bereichen Translation (klinische Studien, IP), Synergie zwischen spezialisierten Einrichtungen und die staatliche Förderung eines deutschen Zentrums für Gesundheitsforschung zum Thema Augenheilkunde gefordert.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ophthalmology has been enormously successful in treating a number of diseases that have a huge impact on patient lives. The development of artificial intraocular lenses in combination with cataract surgery, for example, has restored vision in millions of patients. The intraocular injection of biologics targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in patients with neovascular, age-related macular degeneration or diabetic macular edema has also significantly improved visual outcome. The increase in new treatment modalities over recent decades demonstrates the success of ophthalmological research [1,2,3].

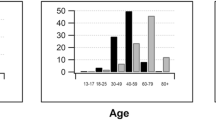

Nevertheless, the majority of age-associated eye diseases cannot be treated adequately, if at all [1,2,3,4]. Since most blinding and visually debilitating eye diseases are related to age and degeneration of retinal neurons and sensory cells, the number of affected patients will increase with ageing societies, as in Germany. As of today, 4–5 million individuals are, for example, affected by age-related macular degeneration (AMD), most of them in an early or intermediate state of disease, where visual defects are mostly compensated. Most of these individuals will move towards severe visual impairment without efficacious treatment options in the near future. Therefore, the need for research in ophthalmology will continue to be high.

The German Ophthalmological Society (DOG) supports research, scientific projects, and studies in the field of ophthalmology both for senior as well as for young scientists in many ways. With the research map [3], the DOG wants to document the performance of scientific ophthalmology in Germany as a research location. The research map appeared in 2022 already in the 4th edition ([3]; previous versions can be viewed at: https://www.dog.org/wissenschaft/forschungslandkarte.) The updated research map is to help the scientific performance of ophthalmology in Germany.

On the international landscape, Germany-based eye research is traditionally ranked in 3rd to 4th place in terms of publications and citations [1,2,3] , with Chinese research activity ever increasing.

To learn from international academic and industry experiences, the “Task Force Research” of the DOG launched an international expert panel review with leading experts in the field to monitor and judge the German research performance and advise on how to improve that in the future. These recommendations shall also be used for informing governmental bodies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

Methods

A web-based international expert panel meeting was held in February 2023 with the above-mentioned international specialists in academic ophthalmology, industry-based ophthalmic research, and research management (Sascha Fauser [Global Head Ophthalmology pRED, Roche, Basel, Switzerland], Martin Gliem [Senior Principle Medical Director, Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany], John Marshall [Frost Professor of Ophthalmology, UCL London, UK], Christian Roesky [CEO, Novaliq GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany], José-Alain Sahel [Distinguished Professor of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, USA] and Paul Sieving [former director NEI, Professor, UC Davis, California, USA]). Experts prior to the meeting received the “Forschungslandkarte” of the DOG to be informed on German Ophthalmic Research Performance [3].

The online meeting was held as an open discussion with members of the Task Force Research of the DOG (Marius Ader, Claus Cursiefen, Horst Helbig, Wolf Lagrèze, Ursula Schlötzer-Schrehard, Marius Ueffing; affiliations see title page). The meeting was recorded and a consensus paper distilled thereof, which was approved by all participants.

Results

The “Research Map” of DOG (https://www.dog.org/wissenschaft/forschungslandkarte) portrays an impressive performance in eye research in Germany and the spectrum of topics addressed by German ophthalmology is equally impressive especially when considering its limited resources when compared to other fields of medical research. Research has improved to a level of leading the field internationally in some areas over the years. An increasing number of active research centers is noted. However, in comparison to other leading countries in ophthalmic research, the amount of funding is very limited. Hence, the expert panel advised DOG the following:

-

1.

The Research Map demonstrates a wide range of research topics in eye and vision science in Germany; however, there seems to be no master plan prioritizing research topics. Furthermore, the research institutions all act on their own goals instead of working together and joining forces. Therefore, the participants propose to define common goals in German ophthalmologic research and to address them in joint efforts (SUGGESTION 1).

-

2.

To increase lobbying activities for increased funding and for raising awareness among funding agencies and politics [5] (SUGGESTION 2).

-

3.

It is also important to focus on engaging more with the society, not only for professionals but to make clear that the DOG is also lobbying for patients (SUGGESTION 3) representing them and their families. This should include some social science to raise awareness and also benefit society in general. Patients will lobby for the DOG if the DOG lobbies for them. Making eye research more relevant to society can also be achieved by working more closely with patient advocacy groups such as Pro Retina (https://www.pro-retina.de/) and DBSV e. V. (https://www.dbsv.org/).

It is important to advocate for eye research as part of the greater picture to point out that the eye is part of the entire body with, for example, multiple implications for internal medicine and neurology/surgery. There are ways to partner and focus on priorities.

-

4.

To improve efficacy, leading centers should take the initiative in proposing a maximum of three areas of priority research and invite others to join their network around clinical unmet needs. With the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) “Schwerpunktprogramm” (SPP; priority program), researchers working on one aspect of ophthalmic research could be brought together to establish one or two focus teams, as exemplarily shown by the recently renewed SPP2127 on Gene- and cell-based therapies to counteract neuroretinal degeneration (https://www.spp2127.de/). DOG could invite the centers with the highest productivity to develop a joint plan to submit applications for SPPs (SUGGESTION 4).

Given the relatively small number of patents in relation to the number of research units, it appears that many universities have not yet realized the potential of patenting and are quite inexperienced in this matter. The understanding that research can be protected and translated into medical practice or industry needs to be strengthened. International experience has shown that breakthrough research is not only dependent on new money but also on new ideas, individual initiative and new technologies. Synergies with the excellent research conducted within the centers of the Max Planck Society should be encouraged.

To develop an understanding of the potential commercial value of what ophthalmic researchers are doing, it is necessary to create a support infrastructure that will help them develop patents and then translate their ideas into practice. Close interactions with the relevant authorities for interventional clinical trials, e.g., with the Paul Ehrlich Institute for interventional biologics, should be fostered. Technology transfer would benefit from more integration with the Fraunhofer Centers network and approach.

-

5.

In order to gain expertise in this field, the DOG could connect to specialized IP (Intellectual Property) attorneys who are familiar with terminology related to ophthalmology and vision research. These attorneys could support framing patent ideas (SUGGESTION 5).

-

6.

Furthermore, the DOG shall organize symposia for young researchers at its annual congress focusing on new opportunities and typical pitfalls. This may be especially important considering the change in the regulatory system for approval in Europe (e.g., Clinical Trials Information System, CTIS). Young researchers need to receive training in technology transfer (SUGGESTION 6).

-

7.

Governmental funding is usually focused on projects that have a high impact on society and community. It is essential to foster knowledge of how to translate research into content and applications that are publicly meaningful and important. This must be publicized. The DOG could help with this by creating public awareness that projects related to eye health are elementary and have a high unmet medical need. Recently, the biotechnology buzz word “GRAIN” was coined standing for genetics, robotics, artificial intelligence and nanotechnology. Ophthalmology is already in a key position to fill in these fields. Improved lobbying in this direction is suggested (SUGGESTION 7).

-

8.

In individual careers, research is often used as a means to become promoted and to obtain access to university positions, but once researchers are appointed, clinical and administrative obligations prevent them from devoting enough time to advance their scientific work. Clinician scientists are finding it increasingly difficult to do research within regular working hours. The DFG’s clinician scientist program has created positions and options for younger clinicians on the level of residents and fellows [6]. However, from a certain career level upwards, there is no protected full or part time leaves for research or weekly research. Parallel to this, economic pressure on departments is increasing with no relief in sight. A greater amount of time for research would allow for more positions for conservative ophthalmologists at the consultancy level and higher up. Way too often, people who are trained to be a clinician scientist end up being pure clinicians. Finally, it is important to orient to visible role models of successful careers and people who are fascinated by science need to attract the younger generation into research Suggestion 8: Lobbying for more permanent career endpoint positions for clinician/medical scientists.

-

9.

Generally, the number of physicians is declining and the demand for clinical care is increasing, so flexible and family-friendly solutions must be developed. Another solution could be to team up with full-time basic or medical scientists at the level of senior physicians. Nearly all German ophthalmological centers have an experimental research facility as part of the clinical department. These teams are likely to foster high quality research. Therefore, new positions and more attractive long-term perspectives (e.g., tenure track options) for advanced basic scientists working in ophthalmology could be a means to prevent constant brain drain and ensure consistent quality of research contents and research infrastructure for translational research. Thus, it is essential to increase recognition of basic scientists working in ophthalmology. To attract the highest qualified individuals into ophthalmology, recognition of basic scientists in a clinical environment as well as in clinical scientific societies must therefore be improved, so that they are not just supporting the work of clinicians. The entire spectrum of research from basic science to clinical research has to be fully acknowledged (SUGGESTION 9). Having said that, “three parties under one roof” are needed to perform translational research: basic scientists, clinical scientists and patients. We have to make sure, also our patients realize that.

Career obstacles should be lowered, ensuring that transition from university to a research organization or a company and back again is eased. The DOG could help in this area by supporting that more career endpoints for basic scientists or medical scientists are needed in ophthalmology (Stiftungsprofessuren—endowed professorships). To recognize the talents of scientists, the DOG could consider creating chairs of excellence that would compensate for the time scientists spend on research at the expense of clinical work. These positions may become prestigious and could be awarded to a limited number of individuals in excellence institutes or emerging centers to promote research.

-

10.

A key objective of the DOG Task Force Research is the establishment of a German Center for Eye Research (Deutsches Zentrum Gesundheitsforschung Augenheilkunde) (SUGGESTION 10) as a German version of the US National Eye Institute. The German Ministry of Health already provides funding for health research centers in some disease areas disregarding ophthalmology. Such a future effort could lead to a (virtual) center and have a special funding scheme similar to the DFG Schwerpunktprogramm (priority program) but with a higher level of financial resources and longer term.

To truly gain public attention and reach politicians, it is important to demonstrate the high impact visual impairment has on society. Collaboration with associations for the visually impaired could help to address issues created by poor vision and raise public awareness. Tremendous costs are associated with poor vision. Health and accident insurance companies have extensive and valid information about the costs of visual handicaps. This represents useful lobbying elements for politicians [5].

Discussion

The research activity in the German ophthalmic community was evaluated by an international expert panel, based on the “Research Map” of DOG 2022 and an oral interview with the Task Force Research of the German Ophthalmological Society DOG.

While the research performance overall was judged positively, several areas for necessary improvement to combat blindness in an aging society [7] were identified.

The main conclusion and suggestions for further improvement to be drawn from this expert panel are summarized in Table 1.

These primarily include i) more lobbying for research funding in ophthalmology, ii) stronger involvement of patient advocacy groups in research planning, iii) more concerted research projects involving several centers of ophthalmic research in Germany, iv) the need to convince society to fund a German National Eye Institute (NEI; i.e., “Deutsches Zentrum für Gesundheitsforschung zum Thema Augenheilkunde”), and v) more translational study and IP activity.

The expert panel will re-evaluate the German research activity in ophthalmology in due course.

References

Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Cursiefen C (2017) Grundlagenforschung in der Ophthalmologie in Deutschland und ihr internationaler Kontext. Ophthalmologe 114(9):804–811

Cursiefen C et al (2019) Unerfüllter Forschungs- und Entwicklungsbedarf in der Ophthalmologie: eine konsensbasierte Roadmap des European Vision Institute für 2019–2025. Ophthalmologe 116(9):838–849

Schaub F, Mele B, Gass P, Ader M, Helbig H, Lagrèze WA, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Ueffing M, Cursiefen C, das DOG Forschungslandkartenteam (2022) Wissenschaftliche Leistung der ophthalmologischen Forschungseinrichtungen in Deutschland 2018–2020: Studien, Publikationen, Drittmittel und mehr – Die Forschungslandkarte der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft (DOG). Ophthalmologie 119(6):582–590

Finger RP et al (2011) Inzidenz von Blindheit und schwerer Sehbehinderung in Deutschland: Projektionen für 2030. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52:4381–4389

Cursiefen C, Colin J, Dana R, Diaz-Llopis M, Faraj LA, Garcia-Delpech S, Geerling G, Price FW, Remeijer L, Rouse BT, Seitz B, Udaondo P, Meller D, Dua H (2012) Consensus statement on indications for anti-angiogenic therapy in the management of corneal diseases associated with neovascularisation: outcome of an expert roundtable. Br J Ophthalmol 96(1):3–9

Howaldt A, Cursiefen C, von Stebut E (2023) Das Cologne Clinician Scientist Programm (CCSP). Ophthalmologie 120:556–558

Zimmermann M, Mauschitz MM, Finger RP, Schuster AK (2023) Weißbuch zur ophthalmologischen Versorgungssituation in Deutschland. DOG, München. https://www.dog.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/DOG-Weissbuch-2023.pdf

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Ader, C. Cursiefen, S. Fauser, M. Gliem, H. Helbig, W. Lagrèze, J. Marshall, C. Roesky, J.-A. Sahel, U. Schlötzer-Schrehard, P. Sieving and M. Ueffing declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

The supplement containing this article is not sponsored by industry.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Based on a Zoom meeting on February 14, 2023 of Task Force Research of the German Ophthalmological Society (DOG); Management: Birgit Mele

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ader, M., Cursiefen, C., Fauser, S. et al. Ophthalmological research in Germany: suggestions by an international expert panel. Ophthalmologie (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-024-02048-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-024-02048-y