Abstract

Environmental clines such as latitude and depth that limit species’ distributions may be associated with gradients in habitat suitability that can affect the fitness of an organism. With the global loss of shallow-water photosynthetic coral reefs, mesophotic coral ecosystems (~30–150 m) may be buffered from some environmental stressors, thereby serving as refuges for a range of organisms including mobile obligate reef dwellers. Yet habitat suitability may be diminished at the depth boundary of photosynthetic coral reefs. We assessed the suitability of coral-reef habitats across the majority of the depth distribution of a common demersal reef fish (Stegastes partitus) ranging from shallow shelf (SS, <10 m) and deep shelf (DS, 20–30 m) habitats in the Florida Keys to mesophotic depths (MP, 60–70 m) at Pulley Ridge on the west Florida Shelf. Diet, behavior, and potential energetic trade-offs differed across study sites, but did not always have a monotonic relationship with depth, suggesting that some drivers of habitat suitability are decoupled from depth and may be linked with geographic location or the local environment. Feeding and diet composition differed among depths with the highest consumption of annelids, lowest ingestion of appendicularians, and the lowest gut fullness in DS habitats where predator densities were highest and fish exhibited risk-averse behavior that may restrict foraging. Fish in MP environments had a broader diet niche, higher trophic position, and higher muscle C:N ratios compared to shallower environments. High C:N ratios suggest increased tissue lipid content in fish in MP habitats that coincided with higher investment in reproduction based on gonado-somatic index. These results suggest that peripheral MP reefs are suitable habitats for demersal reef fish and may be important refuges for organisms common on declining shallow coral reefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suitability of a habitat for an organism can be influenced by environmental parameters that are associated with ecological clines that limit distributions (Sunday et al. 2012) and small-scale habitat variability. For organisms distributed across depths, gradients such as temperature or light can interact with local habitat parameters with consequences for energy allocation and fitness (Munday 2001; Srinivasan 2003). Distributional depth limitations of coral-reef fishes (Brokovich et al. 2008) suggest that habitat suitability may be higher in shallower reef environments, yet processes that may not have a monotonic relationship with depth such as resource availability or predation risk can also influence habitat quality (Hixon and Jones 2005). Many coral-reef fishes with bipartite life cycles have a pelagic larval dispersal stage and remain near their settlement habitat throughout the remainder of their life cycle (Cowen and Sponaugle 2009). Therefore, spatially variable habitat suitability can affect organisms from settlement to maturity, influencing energetic trade-offs (Heino and Kaitala 1999; Catano et al. 2015) and demographic rates of local subpopulations (Goldstein et al. 2016a).

Habitat suitability for demersal reef fishes is dependent on processes that affect growth, reproduction, and condition, such as shelter and food availability (Forrester 1990; Holbrook et al. 2000), with diverse consequences that range from behavioral adaptations to mortality. For example, predation pressure and competition affect resource accessibility, thus influencing survival and fitness of individuals (Hixon and Jones 2005; Figueira and Lyman 2007). Trade-offs between condition, growth, reproduction, and mortality can also regulate behavioral responses of fishes to predation risk, often at the expense of foraging or reproductive output (Holbrook and Schmitt 1988; Dahlgren and Eggleston 2000). Such differences in habitat suitability affect the surplus of energy available for processes such as tissue repair and maintenance, defense and foraging, or demographic rates and reproduction that define fitness (Booth 1995; Munday 2001).

While habitat quality clearly influences demersal reef-fish populations (Almany 2004; Boström-Einarsson et al. 2014), few studies have assessed habitat suitability linked to distributional limitations across the full depth range of a species (Srinivasan 2003; Brokovich et al. 2007; Hoey et al. 2007). Mesophotic coral ecosystems (~30–150 m) that extend to the depth boundaries of photosynthetic hermatypic coral reefs may be important refuges for coral-reef-fish populations (Lindfield et al. 2016) and sources of larval supply for degraded shallow reefs (Lesser et al. 2009). Coral-reef habitats extend into mesophotic depths; however, depth limitations and distributions of coral-reef fishes may be driven by habitat suitability that influences the capacity of reefs at depth peripheries to support viable subpopulations.

The overarching goal of this study was to identify and quantify the processes that affect habitat suitability across the depth distribution of a coral-reef fish (Stegastes partitus). Habitat suitability and energetic trade-offs were assessed based on environmental and biological parameters that influence fitness of demersal coral-reef fishes: (1) predation; (2) time allocation and behavior; (3) diet composition; and (4) C:N ratio as a proxy for lipid content. In declining coral-reef habitats, understanding habitat suitability and the influence of environmental constraints across depths provides insight into the factors that limit vertical distributions of coral-reef fishes and the sustainability of peripheral mesophotic coral ecosystems.

Methods

This study took place during summer (June to September) from 2012 to 2015 at mesophotic depths (MP, 60–70 m) at nine replicate sites at Pulley Ridge on the west Florida Shelf and two replicate deep shelf (DS, 20–30 m) and shallow shelf (SS, <10 m) sites in the Florida Keys (Electronic supplementary material, ESM, Fig. S1). MP sites are geographically separated from SS and DS locations by ~200 km, but oceanographic currents connect the two regions (Vaz et al. 2016). Stegastes partitus is a common territorial demersal reef fish with a small home range, and identifiable feeding, aggression, courtship, and reproductive behaviors (Myrberg 1972). Peak spawning occurs during summer at sunrise, ~1–7 d after the full moon, during which time demersal eggs are guarded by males (Schmale 1981). Stegastes partitus undergo an ontogenetic diet shift from a juvenile diet that includes benthic algae to a planktivorous adult diet (Emery 1973).

Fish collections

Stegastes partitus >30 mm standard length (SL) were collected by SCUBA divers using hand nets and the anesthetic quinaldine. Samples from SS and DS sites were preserved on ice, and samples from MP were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen except during peak spawning when ovaries were extracted and preserved in 10% phosphate buffered formalin, and bodies were frozen. Fish from all strata were stored at −80 °C. SL was measured to the nearest 0.01 cm, and fish bodies and ovaries were weighed to the nearest 0.01 g. MP samples were weighed after freezing; therefore, body weights were converted to fresh weight using the formula from Thorstad et al. (2007):

During peak spawning, ovaries from MP fish were weighed to the nearest 0.01 g and converted to fresh weight following Hunter (1985). Converted ovary weight was added to body weight to obtain total body weight. Results of statistical analyses were equivalent with and without weight conversions.

Predator density and behavior

Predator densities were calculated using visual surveys at SS and DS sites and remotely operated vehicle (ROV) surveys at MP sites. Diver visual survey data from SS and DS strata for the years 2012 and 2014 were obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center. Surveys were conducted using a probabilistic sampling approach during the summer months. Two SCUBA divers identified and counted all fish within paired visual survey cylinders, each with a standard 7.5-m radius, or a 4-m radius if visibility was <7.5 m and >4 m. Predator densities were calculated using the area of the survey cylinder and the mean of the paired counts. Detailed survey methods are described by Smith et al. (2011). MP fish densities were analyzed using data from 99 ROV (UNCW Super Phantom S2) transects from the summers of 2012 and 2013. Each 100-m transect had an estimated 5-m width field of view and was conducted during daylight hours. Detailed ROV methods are described in Reed et al. (2015).

Species were classified as predators following Randall (1967) and Nemeth (1998), or based on diet at the family level from FishBase (Froese and Pauly 2017). ROV footage generally underestimates fish densities in comparison with visual surveys (Andaloro et al. 2013). To correct for this discrepancy, predator densities were calculated using each method in an overlapping region in the Dry Tortugas using visual surveys from 2012 and 2014, and ROV surveys from 2012 and 2013. Surveys for comparison were restricted to 28–35 m depths to encompass an overlapping depth range. A correction factor was calculated by dividing the average predator density from visual surveys by the average from ROV surveys, generating a correction factor of 17.3 that was applied to all ROV predator densities. Diver visual surveys for predator density calculations in SS and DS strata were confined to the forereef zone in the lower Florida Keys (longitude range: 81.98934 W to 81.18103 W) to most closely match the habitats used for sample collections. Predator densities were compared among depth strata using a Kruskal–Wallis test with a Dunn’s post hoc test.

Stegastes partitus behavior was quantified at SS and DS strata with up to four digital GoPro Hero 3 cameras that were positioned on the substrate at the beginning of a dive with each camera aimed at a haphazardly selected mature fish (>40 mm SL; Goldstein et al. 2016a) from a distance of ~0.5 m. Cameras were undisturbed to allow the fish to resume normal behavior until collection at the end of the dive. Stegastes partitus behaviors have a diurnal pattern (Myrberg 1972); therefore, cameras were deployed between 1000 and 1600 h to ensure that all recordings were comparable.

A total of 21 SS and 19 DS videos were analyzed based on 5 min of continuous footage beginning >30 s after the diver was out the frame. Seven behavior categories were quantified based on Myrberg (1972): shelter; out of view; plankton bites; benthic bites; vertical swim; aggression; and courtship. Shelter included time in the shelter, hiding, and evasive downward swimming. Out of view included swimming beyond the camera view or behind an object and was generally associated with swimming long horizontal distances. Plankton bites were feeding motions in the water column as opposed to benthic bites. To determine an approximate vertical swim distance, a meter stick with markings every 15 cm was held vertically at multiple distances from the camera and near the territory of the focal individual at the start of each behavioral recording. The estimated maximum vertical distance traveled for all fish based on 15-cm intervals was ~60 cm. Therefore, for analyses, vertical swim was included as a binary variable in analyses with categories <30 cm or >30 cm to minimize the influence of edge distortion from GoPro videos (Letessier et al. 2015) in our estimates of swimming distance. All videos used for analysis had a field of view that encompassed the vertical swimming range of the fish. Aggression combined conspecific and interspecific chasing, circling, and nipping. Courtship behaviors included a dipping motion, swimming in a tilted position, nudging, and leading or following a conspecific. Shelter, aggression, and courtship were quantified as the amount of time dedicated to each activity divided by the total amount of time that the fish was in view during the 5-min video. Out of view was the amount of time that the fish was not in view divided by the total 5 min. Plankton bites and benthic bites were counts of individual bites per minute that the fish was in view.

Behavioral data comparisons among depth strata were analyzed with principal component analysis (PCA) using a correlation matrix after Box–Cox transformation of variables. Vertical swim was a binary variable. PCA is robust to variation in the precision of the dataset, and with binary variables an object distance is the square root of the complement of the simple matching coefficient (Legendre and Legendre 2012). Individual fish behaviors were used for hierarchical clustering using Ward’s clustering method based on Euclidian distance, and the tree was cut at a distance of 12 to obtain three clusters.

Gut contents

Stegastes partitus for gut content analysis were >30 mm SL to eliminate the influence of ontogenetic diet shifts, and all fish were collected between 0830 and 1700 h (ESM Fig. S2b) to minimize diurnal effects on feeding and fluctuations in prey assemblages. Stomach contents were extracted immediately after thawing, and wet weight was recorded to the nearest 0.001 mg using a Sartorius MP2 microbalance. A subsample of approximately one-third of the total wet weight was separated and weighed for diet identification. Stomach contents from the subsample were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible and counted. Algae, Trichodesmium sp., and unidentifiable items could not be counted. Therefore, dry weights were obtained using four gut content categories: algae (benthic and phytoplankton); animal; Trichodesmium sp.; and unidentified items that were primarily partially digested material. Stomach contents were dried at 50 °C until a stable weight was maintained (~48 h) and then weighed to nearest 0.001 mg.

Stomach contents were analyzed at multiple levels. Gut fullness was calculated using the wet weight of stomach contents and then compared among depth strata using ANCOVA with fish body weight as the covariate, followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparisons. Diet composition was compared by calculating the percent composition of stomach content dried weight summed across all fish within each depth stratum (NSS = 16, NDS = 20, NMP = 20).

Individual prey items were also counted and calculated as counts mg−1 of stomach content wet weight. The dataset used for analysis excluded 11 rare taxa with <20 observations for a total of nine common prey items: Annelida; Appendicularia; Crustacea; Ostracoda; copepods (individuals that could not be identified to a finer taxonomic resolution); calanoid copepods; cyclopoid copepods (included some poeciliid copepods); harpacticoid copepods; and eggs. Variability in prey composition among individual fish and depth strata was assessed using a PCA of Hellinger-transformed data. Relationships between variability in diet composition and depth strata were determined by hierarchical clustering performed on diet count data using Euclidian distance and Ward’s clustering method. The tree was cut at a Euclidean distance of 3.0 to obtain three clusters. Additionally, percent composition of animal prey was compared among depth strata by calculating the count mg−1 of each dominant taxonomic category divided by the sum of the count mg−1 of the dominant taxonomic groupings for each individual fish. To minimize the number of separate comparisons and for ease of interpretation, all crustaceans were combined into a single Crustacea category with lower taxonomic resolution. The results are presented as boxplots that show the range in percentage diet composition among and within each depth stratum.

Stable isotopes

Frozen muscle tissue of fish >30 mm SL was dried at 50 °C until a stable weight was maintained. Dried tissue was ground into a powder and 0.5–1.5 mg of tissue from each fish was weighed in a tin capsule. Benthic algae samples, a mixture of non-calcareous turf algae and Dictyota sp., were collected during the summer months from SS (three replicates from 2013), DS (two replicates from 2013 and one from 2014), and MP (three replicates from 2013) strata, and stored frozen at −20 °C. All epiphytes were removed from algae before drying at 50 °C, and 1–2 mg of algae was analyzed per sample. At SS sites, copepods were collected using diver-towed nets during July of 2013 and August of 2014 and stored at −20 °C in water from the site. Copepods were isolated from net tows, replicate sites were combined to obtain enough tissue, and 0.5–1.5 mg dried sample tissue was weighed for analysis. Divers were unable to tow nets at mesophotic depths; consequently, copepods were sorted from five replicate light traps from each stratum (SS and DS: two from 2012 and three from 2013, MP: two from 2013 and three from 2014). Samples were preserved in 95% ethanol; the effects of ethanol storage on isotope values are likely to be minimal and uniform because all copepod light trap samples were preserved using the same methods (Arrington and Winemiller 2002), and there is evidence that ethanol preservation does not affect δ15N in fish tissue (Kelly et al. 2006). The δ13C and δ15N of the samples were analyzed at the University of Miami using mass spectrometry on a Costech EA 4010 connected to a Thermo Delta V Advantage. Isotope values of δ13C and δ 5N are reported using delta notation, and values are relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) and atmospheric N2, respectively, with ± 0.1‰ typical precision measurements of the standards.

Isotope δ13C values from fish muscle tissue were corrected for high lipid content for all analyses based on an average C:N ratios >3.5, using the formula:

where δ13Cuntreated is the value prior to correction (Post et al. 2007). Trophic positions of S. partitus were calculated using the formula:

where λ is the trophic position of the lower trophic organism that is used to obtain δ15Nbase, starting with a value of 1 for primary producers, and Δ n is the δ15N enrichment for each trophic level (Post 2002). δ15Nbase was calculated for each stratum using the mean isotope value of copepods collected in light traps. The trophic position of copepods was estimated as 2.5 based on the enriched δ15N of light trap collections compared to smaller copepods from net tows at the SS stratum (see Results) and the omnivorous diet of many copepods (Kleppel et al. 1996). A Δ n value of 3.5 was used for trophic enrichment (Post 2002). A trophic position formula utilizing only pelagic food webs was selected based on low benthic bite rates from video analyses (mean benthic bites = 1.1 min−1 compared to mean plankton bites = 21.9 min−1), and minimal algae in gut contents across all depth strata (see Results). Trophic position was calculated for individual fish and compared among depth strata using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc tests.

The ratio of carbon to nitrogen percent weight in tissue (C:N) from stable isotope analyses was compared among strata as a proxy for tissue lipid content. Lipids are depleted in δ13C relative to other tissue types, resulting in a positive linear relationship between C:N and lipid content (Post et al. 2007). C:N ratios were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with depth strata and sex as factors, followed by Tukey post hoc tests. The model was simplified by systematically removing nonsignificant terms.

Trophic breadth was assessed based on the range of δ15N values within each depth stratum, and the variability of basal resources was inferred from δ13C (Layman et al. 2007). Isotope niche width was estimated by calculating the extent of δ15N and δ13C in biplot space using the area of a convex hull for each depth stratum and standard ellipse areas that were estimated by Bayesian inference with a correction for small sample sizes based on a bivariate normal distribution (Jackson et al. 2011). Uncertainty in ellipse area estimates for comparisons among strata were calculated with 104 posterior draws of the standard ellipse area to generate probabilities. All isotope niche width calculations were performed using the library SIAR (Parnell et al. 2010).

Energy allocation

A PCA was computed using trophic position, C:N ratio, age, gut fullness, and gonado-somatic index (GSI: Weightovary/Weightbody × 100) to visualize the trade-offs associated with diet, age, and reproduction for individual fish. Otolith-derived ages and GSI for females that were collected during peak spawning were obtained from a previous study (Goldstein et al. 2016a). All data were analyzed with R version 3.1.2; multivariate analyses were performed using the FactoMineR package, and meaningful components were determined based on Kaiser–Guttman criterion (Legendre and Legendre 2012).

Results

Predator density and behavior

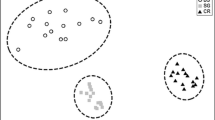

Predator densities differed significantly among sites and did not have a monotonic relationship with depth: the highest densities were found in the DS strata, with no significant differences between SS and MP (Table 1). Behavioral PCA analyses showed separation of SS and DS fish behaviors along PC2 and minimal separation along PC1, explaining 21.5% and 31.5%, respectively, of the variation in the dataset (Fig. 1). The behaviors that had strong positive correlations with PC1 were out of view and plankton bites compared to negatively correlated benthic bites, courtship, shelter, and aggression. PC2, which showed the most differentiation between SS and DS sites was most strongly correlated with vertical swim, aggression, courtship, and shelter (Fig. 1). Clustering analysis revealed three major behavioral groups with some depth-related patterns. Cluster 1 was primarily composed of SS fish that had a higher frequency of benthic bites, but swam long vertical distances, were aggressive, and spent a large portion of time in courtship (Fig. 1). Cluster 2 included both SS and DS fish that dedicated time to feeding or were out of view, a behavior that was typically a result of swimming long horizontal distances. Cluster 3 consisted of 1 SS fish and 6 DS fish that spent the majority of their time sheltering.

Principal component analysis of Stegastes partitus behaviors at SS (shallow shelf, white) and DS (deep shelf, gray) strata. The points in the biplot are individual fish scores, and the vectors depict the loadings of each behavioral variable. The angles between vectors reflect their correlations; arrow direction and vector length reflect the direction and the strength of the variables. Hierarchical clusters using Ward’s method based on Euclidean distance are identified by shape

Gut contents

Stegastes partitus in SS habitats had significantly fuller guts than fish from the DS strata, while those from the MP strata had intermediate values were that were not significantly different from other depths (Table 1). Percentage composition of broad diet categories showed that among all depths fish fed primarily on plankton, with the majority of diets composed of Trichodesmium sp. (SS: 56%, DS: 52%, MP: 52%), followed by animals (primarily copepods, SS: 18%, DS: 21%, MP: 22%), and the lowest contribution from algae (both benthic and planktonic; SS: 4%, DS: 6%, MP: 4%), with ~20% unidentifiable material from all strata. Crustaceans and Appendicularia were the most common animal prey items in S. partitus diets across depth strata, but showed high variability within each stratum (Fig. 2). Prey composition primarily differed with respect to high ingestion of Annelida and low consumption of Appendicularia in DS habitats, and a high median consumption of Crustacea in MP habitats (Fig. 2; ESM Fig. S3). Within each depth stratum, there was a large amount of individual variability in diet composition based on the broad interquartile range of percent composition and PCA analyses (Fig. 2; ESM Fig. S3). Hierarchical clustering separated diets into three groups that were related to consumption of Annelida, copepods, and a third group related to ingestion of Appendicularia (ESM Fig. S3).

Percentage composition of the gut contents of Stegastes partitus based on common prey item counts per stomach content wet weight (mg) comparing shallow shelf (SS, white), deep shelf (DS, gray), and mesophotic (MP, black) depth strata. The categories shown (Annelida: Ann, Appendicularia: App, Crustacea: Crust, and eggs from unknown sources: Eggs) are the most dominant animal groups in S. partitus guts that together comprise ~20% of the total content. Boxplots show the median, the distance between the first and third quartiles (interquartile range), and the whiskers which include data within 1.5 times the interquartile range

Stable isotopes

Comparison of mean δ13C and δ15N of S. partitus, copepods, and benthic algae showed the expected increase in δ15N with increasing trophic level (ESM Fig. S4). For algae and copepods, δ15N differed minimally among depths, whereas increasing depth yielded progressively depleted δ13C. Small copepods from diver-towed nets were δ15N depleted compared to larger copepods from light traps (ESM Fig. S4). Isotope values of S. partitus showed depletion of δ 13C and enrichment of δ 15N values in fish muscle with increasing depth. Published values indicate that Trichodesmium sp. has extremely depleted δ15N values and previous studies in the Florida Keys revealed greater differences in algal δ15N between depths than measured in our study (ESM Fig. S4). Stegastes partitus were less δ15N enriched than herbivorous dusky damselfish, similar to ocean surgeonfish, and more enriched than parrotfishes (ESM Fig. S4; ESM Table S1).

Stegastes partitus trophic position increased with increasing depth (Fig. 3a), resulting in a significantly higher trophic position for fish from MP depths compared to shallower strata (Table 1). The C:N ratio of MP fish muscle tissue was also significantly higher than SS and DS fish (Table 1; Fig. 3b). Biplots of δ13C and δ15N values showed the broadest width of δ13C values at MP strata, and a similar span of δ15N (Fig. 4). Convex hull area and standard ellipse area increased with depth, and Bayesian credible intervals indicated that MP fish had a broader isotopic niche than the other two strata (Table 1; Fig. 4).

Stable isotope results depicting a mean (±SE) trophic position and b mean (±SE) carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratios of Stegastes partitus >30 mm standard length at each depth stratum (SS shallow shelf, DS deep shelf, MP mesophotic). Letters designate significant differences (ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests, p < 0.05)

Stable isotope δ13C and δ15N biplot of Stegastes partitus isotope niche space in each depth stratum: shallow shelf (SS, red circles), deep shelf (DS, blue triangles), mesophotic (MP, white circles). Dotted lines represent the isotope convex hull area. Solid lines are standard ellipse areas that were calculated using 104 bootstraps in Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses (SIBER in R), with a correction for small sample sizes

Energy allocation

Relationships between all diet and growth variables were strongly associated with PC1 which explained 68.8% of the variability in the dataset. MP fish had the highest PC1 scores and were characterized by higher trophic position, GSI, C:N ratio, and older ages than fish from shallower depth strata (Fig. 5). In contrast, SS fish had the lowest PC1 scores and were associated with low gut fullness (Fig. 5). SS and DS fish primarily diverged with respect to gut fullness along PC2 which explained 14.9% of the variation in the dataset (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Habitat suitability influences behavior and resource availability and thus underlies energetic trade-offs and potentially fitness in coral-reef fishes. The mechanisms that determine habitat suitability may be the result of patchy habitat variability, or be linked to depth gradients or horizontal clines. Across the depth distribution of S. partitus, predation risk and associated behavioral trade-offs are mechanisms that may restrict food accessibility, with consequences for diet quality, tissue C:N ratio, and energetic investment in costly growth and reproduction. At the depth boundaries of most coral-reef organisms, S. partitus has high reproductive investment and likely higher fitness than shallow water populations, indicating that habitat suitability may be decoupled from the processes that limit distributions and abundance across depths (Goldstein et al. 2016b).

Variation in predator density suggests that predation risk may affect time allocated to potentially important feeding and reproductive behaviors by S. partitus. Behaviors grouped primarily into three categories: (1) those that increase predation risk, including vertical swimming distance, aggression, and courtship (Myrberg 1972; Figueira and Lyman 2007); (2) those associated with feeding; and (3) “timid” sheltering behavior. Between SS and DS strata, patterns suggest that S. partitus invests similarly in behaviors associated with feeding, a process necessary for physiological maintenance, growth, and survival. Comparing behavioral patterns with the greatest contrast between SS and DS strata indicates that many individuals in DS habitats with the highest predator densities sheltered often and remained near the benthos. In contrast, “risky” behaviors that can elicit trade-offs between survival and maximizing fitness (Holbrook and Schmitt 1988; Figueira and Lyman 2007) were more common in SS habitats, where predator densities were lower. Higher predator densities in DS habitats combined with timid behavior suggest that these fish may be minimizing predation risk, but there are likely additional fitness consequences. Spatially variable predation risk that is not directly associated with depth may be an important component of habitat suitability that affects critical feeding and reproductive behaviors.

Energy surplus and the allocation of energy to physiological processes are influenced by food availability, accessibility, and selectivity that determine diet quality (Brooker et al. 2013). Gut fullness and prey item composition of S. partitus showed subtle differences across depths, and for the primarily planktivorous fish, diet and food availability are a function of plankton community composition that is affected by regional oceanography (Govoni et al. 2010). Reefs at Pulley Ridge are primarily influenced by the Loop Current that brings warm oligotrophic water to mesophotic depths (Jarrett et al. 2005). In the Florida Keys, eddies are predominant features that deliver pulses of plankton to reef habitats (Sponaugle et al. 2005) and upwell nutrient-rich water associated with higher food availability and faster growth of larval fish (Shulzitski et al. 2015). Planktonic food availability is influenced by dynamic oceanographic processes that vary across space and time (Lee et al. 1992), and study locations were separated by depth as well as geographic location suggesting that both spatial scales may affect food availability for S. partitus. Across depths, tidal bores regularly deliver cold nutrient-rich water and plankton to DS reefs more frequently and for longer duration than to SS reefs (Leichter et al. 2003). Although not measured directly, the availability of planktonic prey is likely higher in DS habitats compared to SS (Leichter et al. 1998). Despite the expectation of higher food availability in deeper habitats, gut fullness was highest in SS reef fish and comparable between SS and MP environments. SS and MP environments had lower predator densities than DS habitats, suggesting that the “risky” behaviors of fish in SS environments may increase their access to planktonic food sources (Motro et al. 2005). Diet may be related to local oceanography that was not captured by our study; however, behavioral patterns suggest that predator avoidance or associated environmental stressors (Schrandt and Lema 2011) may also limit access to food sources and consumption for fish in DS habitats.

Gut content analysis provides data on short-term diet composition and stable isotopes reveal long-term feeding habits, nutrient source pools, trophic level, and diet breadth. Broadly, S. partitus diets were primarily planktonic and were largely composed of Trichodesmium sp. and animal material. Finer-scale identification of animals ingested by S. partitus revealed that the median consumption of crustaceans was slightly higher for MP fish, and fish in DS habitats ingested the greatest proportion of annelids and fewer appendicularians than other depths. Prey composition suggests a unique diet in intermediate depth ranges where reproductive investment is also lowest (Goldstein et al. 2016a). Diet composition was variable among individuals within each depth stratum and can be coarsely grouped into consumers of copepods, appendicularians, or annelids, suggesting that S. partitus consistently consume particular prey types but that there is variability within the relative proportions consumed. Variability in major prey categories and diets within and among depths can be the result of local zooplankton communities, prey availability, and diet selectivity (Llopiz et al. 2010). Along the Florida Keys reef slope, the available zooplankton communities associated with frequent tidal bores in DS habitats may differ from shallower SS environments that are less influenced by breaking internal waves (Leichter et al. 2003). Compared to SS and DS reefs, MP habitats in the Gulf of Mexico are more strongly influenced by the meandering Loop Current that can deliver water from the Caribbean or the northern Gulf of Mexico before reaching the west Florida Shelf (Jarrett et al. 2005). Diet composition suggests that for planktivous reef fish with a coarsely invariable diet, reef environments and likely oceanography across the Florida Shelf can influence finer-scale animal prey composition.

Isotope patterns from shallow to deeper environments revealed differences among depth strata with a slight enrichment of δ15N that is associated with trophic level and substantial depletion of δ13C that is generally associated with nutrient source pools (Post 2002). Isotope analysis of trophic position and diet breadth is dependent on a thorough knowledge of baseline isotope values and nutrient source pools (Layman et al. 2007), and in the Florida Keys, isoscapes vary across depths. Particulate organic matter δ13C values are typically depleted from inshore to offshore (Lamb and Swart 2008), coinciding with our results from SS (more inshore) to MP (further offshore) sites. Benthic algae isotope values are linked to upwelling of enriched δ15N sources and mixing with depleted surface waters (Leichter et al. 2003), and while differences were not extreme, typical patterns of enrichment with depth were reflected in δ15N values of benthic algae in our study. Among fish species, the depleted δ15N of S. partitus compared to another Stegastes species, the dusky damselfish, reflects their planktivorous diet and Trichodesmium sp. consumption, compared to the benthic-derived diet of the dusky damselfish (Lamb-Wozniak 2007). Stegastes partitus in the MP strata had a broader isotopic diet niche and higher trophic position than SS and DS fish, coinciding with slightly higher consumption of crustaceans and supporting the assertion that MP fish diets differ from those in the shallower reef habitats in the Florida Keys. Total isotopic niche area is the result of trophic breadth and variability in nutrient source pools (Layman et al. 2007). The ranges of δ15N in fish muscle tissue were similar among depth strata; thus, the larger isotope niche area in MP habitats was primarily the result of broader nutrient sources. Isotopic niche area of SS and DS strata that were closer both geographically and across depths overlapped, indicating similar resource use and source pools (Hammerschlag-Peyer et al. 2011). This difference in δ13C width and lack of niche overlap between MP and Florida Keys habitats implies a varied and unique nutrient source pool for fish in MP habitats, and the probable effects of dynamic oceanography on delivery of nutrients and planktonic food sources to Pulley Ridge. This variable oceanographic environment is also reflected in greater sub-seasonal temperature variation at MP compared to SS and DS strata (Goldstein et al. 2016a).

Increasing trophic level and concomitant increases in C:N ratio across study locations suggest that differences in food quality may affect energy availability. The highest C:N ratio in MP fish and similar C:N between SS and DS fish, despite timid behavior and low gut fullness in DS habitats, suggests that subtle differences in diet composition impact tissue C:N that is correlated with lipid content. SS fish that had full guts yet ingested slightly more Trichodesmium sp. than fish from other depth strata may obtain disproportionately lower additional energy from increased food consumption, contributing to an overall lower C:N ratio. Trichodesmium sp. may be a low-quality food source that is secondarily ingested by fish while they target zooplankton (Eberl and Carpenter 2007) despite evidence of consumption of the diazotrophic cyanobacteria by other pomacentrids (Emery 1973). Lower densities of S. partitius in deeper environments (Goldstein et al. 2016b) suggest that SS fish may also be influenced by competition that can affect energy allocation and condition (Samhouri 2009). In DS habitats, lower rates of aggression suggest that intraspecific competition does not account for lower gut fullness. Consequently, the basis for the low trophic level and C:N ratio of DS fish is less clear, although DS fish may have reduced access to high-value prey as a result of zooplankton community composition or increased sheltering and predator-constrained vertical foraging height (Motro et al. 2005). In MP habitats, higher trophic position and increased C:N ratio may be indicative of a higher quality diet and increased fish condition (Malzahn et al. 2007).

The relationship between diet, C:N ratio, age, and GSI suggests that the combination of these processes reflect energetic trade-offs for individual fish and that much of the variability in energy allocation and trade-offs occurs between, rather than within, each depth stratum. Reproductive investment was positively related to traits associated with MP fish populations that are composed of old, large, long-lived, slow-growing individuals with high reproductive investment in oocytes and high batch fecundity in comparison with fish on shallower reefs (Goldstein et al. 2016a), suggesting energetic trade-offs associated with age, growth rates, reproduction, and diet quality. Reproductive investment is a combination of (1) fecundity and investment in individual oocytes, processes quantified by GSI and (2) frequency of spawning that is not captured by GSI (Maddams and McCormick 2012). Warmer water temperature in SS habitats (Goldstein et al. 2016a) may increase spawning frequency (Yoneda et al. 2014), explaining the discrepancy between high frequency of courtship behavior and low GSI for SS fish. In MP habitats where fish have a higher trophic position, high C:N ratio, large body size, are older, and may reproduce less frequently (Goldstein et al. 2016a), energetic trade-offs may favor high reproductive investment in spawning batches in contrast to energetically costly processes such as foraging and growth.

The results of this study highlight the influence of habitat variability on reef-fish behavior and diet and the role of environmental conditions in determining habitat suitability and fitness. However, there are limitations to the study due to the geography of the reef tract and the constraints of sampling in mesophotic environments. Behavioral analyses were restricted to SS and DS environments as a result of limited bottom time for SCUBA divers in MP habitats. While behavioral data from MP environments would strengthen the relationship between behavior, diet, and habitat suitability, the patterns observed in SS and DS reefs provide insight into the potential role of local habitat parameters such as predator densities that may decouple habitat suitability from depth constraints. Geographically, MP habitats are separated from DS and SS reefs by ~200 km. As a result, depth gradients could not be sampled across a continuum and co-vary with geographic location. This reef configuration and associated sampling design limit the ability to disentangle the influence of depth or geography on the observed patterns. Nevertheless, our results from SS and immediately adjacent DS reefs suggest that habitat variation associated with depth can influence habitat suitability across distances of only a few kilometers. Additionally, reefs in the Florida Keys are oceanographically connected to MP reefs at Pulley Ridge and connectivity is likely for S. partitus populations (Vaz et al. 2016), suggesting that some processes that vary over geographic distances may confound the influence of depth on S. partitus populations while others such as connectivity and isolation can be excluded.

Energetic trade-offs of demersal reef fishes are influenced by processes that can vary monotonically with depth such as temperature (Goldstein et al. 2016a) or oceanographically driven diet and food availability (Leichter et al. 1998), yet are likely mediated by patchy and less spatially predictable parameters such as predation risk. Low food consumption, lower condition, and reduced energy allocation to reproduction (Goldstein et al. 2016a) in DS habitats indicate a significant role of predators and diet in shaping habitat suitability for demersal reef fish. Environmentally driven trade-offs affect individual fitness and can potentially scale up to influence population dynamics and larval production across the geographic or depth distribution of a species (Goldstein et al. 2016b). Results of this study highlight the variable nature of habitat suitability that is driven by a suite of physiological, behavioral, and oceanographic processes that are spatially patchy or linked to environmental gradients, and suggests that peripheral coral ecosystems at distributional margins can be suitable habitats for coral-reef-fish populations.

Change history

02 June 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Almany G (2004) Differential effects of habitat complexity, predators and competitors on abundance of juvenile and adult coral reef fishes. Oecologia 141:105–113

Andaloro F, Ferraro M, Mostarda E, Romeo T, Consoli P (2013) Assessing the suitability of a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to study the fish community associated with offshore gas platforms in the Ionian Sea: a comparative analysis with underwater visual censuses (UVCs). Helgol Mar Res 67:241–250

Arrington DA, Winemiller KO (2002) Preservation effects on stable isotope analysis of fish muscle. Trans Am Fish Soc 131:337–342

Booth DJ (1995) Juvenile groups in a coral-reef damselfish: density-dependent effects on individual fitness and population demography. Ecology 76:91–106

Boström-Einarsson L, Bonin MC, Munday PL, Jones GP (2014) Habitat degradation modifies the strength of interspecific competition in coral dwelling damselfishes. Ecology 95:3056–3067

Brokovich E, Einbinder S, Kark S, Shashar N, Kiflawi M (2007) A deep nursery for juveniles of the zebra angelfish Genicanthus caudovittatus. Environ Biol Fishes 80:1–6

Brokovich E, Einbinder S, Shashar N, Kiflawi M, Kark S (2008) Descending to the twilight-zone: changes in coral reef fish assemblages along a depth gradient down to 65 m. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 371:253–262

Brooker RM, Jones GP, Munday PL (2013) Prey selectivity affects reproductive success of a corallivorous reef fish. Oecologia 172:409–416

Catano LB, Gunn BK, Kelley MC, Burkepile DE (2015) Predation risk, resource quality, and reef structural complexity shape territoriality in a coral reef herbivore. PLoS ONE 10:e0118764

Cowen RK, Sponaugle S (2009) Larval dispersal and marine population connectivity. Annu Rev Mar Sci 1:443–466

Dahlgren CP, Eggleston DB (2000) Ecological processes underlying ontogenetic habitat shifts in a coral reef fish. Ecology 81:2227–2240

Eberl R, Carpenter E (2007) Association of the copepod Macrosetella gracilis with the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium spp. in the North Pacific Gyre. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 333:205–212

Emery AR (1973) Comparative ecology and functional osteology of fourteen species of damselfish (Pisces: Pomacentridae) at Alligator Reef, Florida Keys. Bull Mar Sci 23:649–770

Figueira WF, Lyman SJ (2007) Context-dependent risk tolerance of the bicolour damselfish: courtship in the presence of fish and egg predators. Anim Behav 74:329–336

Forrester GE (1990) Factors influencing the juvenile demography of a coral reef fish. Ecology 71:1666–1681

Froese R, Pauly D (eds) (2017) FishBase. www.fishbase.org

Goldstein ED, D’Alessandro EK, Sponaugle S (2016a) Demographic and reproductive plasticity across the depth distribution of a coral reef fish. Sci Rep 6:34077

Goldstein ED, D’Alessandro EK, Reed J, Sponaugle S (2016b) Habitat availability and depth-driven population demographics regulate reproductive output of a coral reef fish. Ecosphere 7:e01542

Govoni JJ, Hare JA, Davenport ED, Chen MH, Marancik KE (2010) Mesoscale, cyclonic eddies as larval fish habitat along the southeast United States shelf: a Lagrangian description of the zooplankton community. ICES J Mar Sci 67:403–411

Hammerschlag-Peyer CM, Yeager LA, Araújo MS, Layman CA (2011) A hypothesis-testing framework for studies investigating ontogenetic niche shifts using stable isotope ratios. PLoS One 6:e27104

Heino M, Kaitala V (1999) Evolution of resource allocation between growth and reproduction in animals with indeterminate growth. J Evol Biol 12:423–429

Hixon MA, Jones GP (2005) Competition, predation, and density-dependent mortality in demersal marine fishes. Ecology 86:2847–2859

Hoey J, McCormick M, Hoey A (2007) Influence of depth on sex-specific energy allocation patterns in a tropical reef fish. Coral Reefs 26:603–613

Holbrook SJ, Schmitt RJ (1988) Effects of predation risk on foraging behavior: mechanisms altering patch choice. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 121:151–163

Holbrook SJ, Forrester GE, Schmitt RJ (2000) Spatial patterns in abundance of a damselfish reflect availability of suitable habitat. Oecologia 122:109–120

Hunter JR (1985) Preservation of northern anchovy in formaldehyde solution. In: Lasker R (ed) An egg production method for estimating spawning biomass of pelagic fish: application to the northern anchovy, Engraulis mordax. NOAA Technical Report 36, National Marine Fisheries Service, US Department of Commerce, pp 63–65

Jackson AL, Inger R, Parnell AC, Bearhop S (2011) Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER—Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. J Anim Ecol 80:595–602

Jarrett BD, Hine AC, Halley RB, Naar DF, Locker SD, Neumann AC, Twichell D, Hu C, Donahue BT, Jaap WC, Palandro D, Ciembronowicz K (2005) Strange bedfellows—a deep-water hermatypic coral reef superimposed on a drowned barrier island; southern Pulley Ridge, SW Florida platform margin. Mar Geol 214:295–307

Kelly B, Dempson JB, Power M (2006) The effects of preservation on fish tissue stable isotope signatures. J Fish Biol 69:1595–1611

Kleppel GS, Burkart CA, Carter K, Tomas C (1996) Diets of calanoid copepods on the West Florida continental shelf: relationships between food concentration, food composition and feeding activity. Mar Biol 127:209–217

Lamb K, Swart P (2008) The carbon and nitrogen isotopic values of particulate organic material from the Florida Keys: a temporal and spatial study. Coral Reefs 27:351–362

Lamb-Wozniak KA (2007) Nitrogen cycling on coral reefs: a stable isotopic investigation of nutrient dynamics within the Florida Keys coral reef tract. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Miami, FL, United States

Layman CA, Arrington DA, Montaña CG, Post DM (2007) Can stable isotope ratios provide for community-wide measures of trophic structure? Ecology 88:42–48

Lee TN, Rooth C, Williams E, McGowan M, Szmant AF, Clarke ME (1992) Influence of Florida Current, gyres and wind-driven circulation on transport of larvae and recruitment in the Florida Keys coral reefs. Cont Shelf Res 12:971–1002

Legendre P, Legendre L (2012) Numerical ecology. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Leichter JJ, Stewart HL, Miller SL (2003) Episodic nutrient transport to Florida coral reefs. Limnol Oceanogr 48:1394–1407

Leichter J, Shellenbarger G, Genovese S, Wing S (1998) Breaking internal waves on a Florida (USA) coral reef: a plankton pump at work? Mar Ecol Prog Ser 166:83–97

Lesser MP, Slattery M, Leichter JJ (2009) Ecology of mesophotic coral reefs. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 375:1–8

Letessier TB, Juhel J-B, Vigliola L, Meeuwig JJ (2015) Low-cost small action cameras in stereo generates accurate underwater measurements of fish. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 466:120–126

Lindfield SJ, Harvey ES, Halford AR, McIlwain JL (2016) Mesophotic depths as refuge areas for fishery-targeted species on coral reefs. Coral Reefs 35:125–137

Llopiz JK, Richardson DE, Shiroza A, Smith SL, Cowen RK (2010) Distinctions in the diets and distributions of larval tunas and the important role of appendicularians. Limnol Oceanogr 55:983–996

Maddams JC, McCormick MI (2012) Not all offspring are created equal: variation in larval characteristics in a serially spawning damselfish. PLoS One 7:e48525

Malzahn AM, Aberle N, Clemmesen C, Boersma M (2007) Nutrient limitation of primary producers affects planktivorous fish condition. Limnol Oceanogr 52:2062–2071

Motro R, Ayalon I, Genin A (2005) Near-bottom depletion of zooplankton over coral reefs: III: vertical gradient of predation pressure. Coral Reefs 24:95–98

Munday PL (2001) Fitness consequences of habitat use and competition among coral-dwelling fishes. Oecologia 128:585–593

Myrberg AA (1972) Ethology of the bicolor damselfish, Eupomacentrus partitus (Pisces: Pomacentridae): a comparative analysis of laboratory and field behaviour. Anim Behav Monogr 5:197–283

Nemeth RS (1998) The effect of natural variation in substrate architecture on the survival of juvenile bicolor damselfish. Environ Biol Fishes 53:129–141

Parnell AC, Inger R, Bearhop S, Jackson AL (2010) Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too much variation. PLoS One 5:e9672

Post DM (2002) Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 83:703–718

Post DM, Layman CA, Arrington DA, Takimoto G, Quattrochi J, Montaña CG (2007) Getting to the fat of the matter: models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 152:179–189

Randall JE (1967) Food habits of reef fishes of the West Indies. Studies in Tropical Oceanography 5:655–847

Reed J, Farrington S, Moe H, Harter S, Hanisak D, David A (2015) Characterization of the mesophotic benthic habitat and fish assemblages from ROV dives on Pulley Ridge and Tortugas during 2012 and 2013 R/V Walton Smith Cruises. HBOI Technical Report 157. Cooperative Institute for Ocean Exploration, Research, and Technology at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, Florida Atlantic University, 133 pp

Samhouri JF (2009) Food supply influences offspring provisioning but not density-dependent fecundity in a marine fish. Ecology 90:3478–3488

Schmale MC (1981) Sexual selection and reproductive success in males of the bicolor damselfish, Eupomacentrus partitus (Pisces: Pomacentridae). Anim Behav 29:1172–1184

Schrandt M, Lema S (2011) Habitat-associated intraspecific variation in behavior and stress responses in a demersal coral reef fish. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 443:153–166

Shulzitski K, Sponaugle S, Hauff M, Walter K, D’Alessandro EK, Cowen RK (2015) Close encounters with eddies: oceanographic features increase growth of larval reef fishes during their journey to the reef. Biol Lett 11:20140746

Smith SG, Ault JS, Bohnsack JA, Harper DE, Luo J, McClellan DB (2011) Multispecies survey design for assessing reef-fish stocks, spatially explicit management performance, and ecosystem condition. Fish Res 109:25–41

Sponaugle S, Lee T, Kourafalou V, Pinkard D (2005) Florida Current frontal eddies and the settlement of coral reef fishes. Limnol Oceanogr 50:1033–1048

Srinivasan M (2003) Depth distributions of coral reef fishes: the influence of microhabitat structure, settlement, and post-settlement processes. Oecologia 137:76–84

Sunday JM, Bates AE, Dulvy NK (2012) Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat Clim Chang 2:686–690

Thorstad EB, Finstad AG, Jensen AJ, Museth J, Næsje TF, Saksgård LM (2007) To what extent does ethanol and freezing preservation cause shrinkage of juvenile Atlantic salmon and European minnow? Fish Manag Ecol 14:295–298

Vaz AC, Paris CB, Olascoaga MJ, Kourafalou VH, Kang H, Reed JK (2016) The perfect storm: match-mismatch of bio-physical events drives larval reef fish connectivity between Pulley Ridge mesophotic reef and the Florida Keys. Cont Shelf Res 125:136–146

Yoneda M, Kitano H, Tanaka H, Kawamura K, Selvaraj S, Ohshimo S, Matsuyama M, Shimizu A (2014) Temperature- and income resource availability-mediated variation in reproductive investment in a multiple-batch-spawning Japanese anchovy. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 516:251–262

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research under award NA11NOS4780045 to the University of Miami. Additional funding was received from the David Rowland Fellowship, the RSMAS Alumni Award, the Women Divers Hall of Fame Graduate Scholarship, the University of Miami Graduate Research Fund, and the Harry D. Vernon Scholarship. E.G. was also supported by the University of Miami Fellowship and NOAA NRDA. Sampling was conducted under permit SAL-11-1343C-SR from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and permit FKNMS-2011-125-A3 from the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, and animal handling was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We thank the crews of the M/V Spree, the R/V Walton Smith, and the University of North Carolina at Wilmington Super Phantom S2 ROV, as well as the technical diving team. We also thank J. Reed, S. Farrington, and D. Hanisak (Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute); and Lt. H. Moe, S. Harter, and A. David (NOAA NMFS) for their roles in providing ROV data. P. Swart at the University of Miami provided equipment and expertise for isotope analyses. K. Doering, A. Greer, K. Shulzitski, S. Bignami, C. Guigand, L. Parsons, and numerous volunteers contributed to data collection. Earlier drafts benefited from the comments of R. Cowen, J. Serafy, M. Schmale, and J. Bohnsack.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Biology Editor Dr. Andrew Hoey

The original version of this article was revised.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-017-1593-6.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Goldstein, E.D., D’Alessandro, E.K. & Sponaugle, S. Fitness consequences of habitat variability, trophic position, and energy allocation across the depth distribution of a coral-reef fish. Coral Reefs 36, 957–968 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-017-1587-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-017-1587-4