Abstract

Background

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) can cause structural damage. However, data on conventional radiography (CR) in JIA are scant.

Objective

To provide pragmatic guidelines on CR in each non-systemic JIA subtype.

Methods

A multidisciplinary task force of 16 French experts (rheumatologists, paediatricians, radiologists and one patient representative) formulated research questions on CR assessments in each non-systemic JIA subtype. A systematic literature review was conducted to identify studies providing detailed information on structural joint damage. Recommendations, based on the evidence found, were evaluated using two Delphi rounds and a review by an independent committee.

Results

74 original articles were included. The task force developed four principles and 31 recommendations with grades ranging from B to D. The experts felt strongly that patients should be selected for CR based on the risk of structural damage, with routine CR of the hands and feet in rheumatoid factor-positive polyarticular JIA but not in oligoarticular non-extensive JIA.

Conclusion

These first pragmatic recommendations on CR in JIA rely chiefly on expert opinion, given the dearth of scientific evidence. CR deserves to be viewed as a valuable tool in many situations in patients with JIA.

Key Points

• CR is a valuable imaging technique in selected indications.

• CR is routinely recommended for peripheral joints, when damage risk is high.

• CR is recommended according to the damage risk, depending on JIA subtype.

• CR is not the first-line technique for imaging of the axial skeleton.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a heterogeneous group of chronic inflammatory joint conditions that can cause structural damage [1]. Seven mutually exclusive subtypes of JIA are defined in the 2001 Edmonton classification developed by the International League Against Rheumatism (ILAR) [2]. This classification has been challenged and modifications suggested, such as exclusion of systemic-onset JIA (sJIA) due to its similarity to autoinflammatory diseases [3, 4].

The prevalence of joint damage among patients with JIA has been estimated at 8–27 % in extended oligoarticular JIA (oJIA), 35–67 % in polyarticular JIA (pJIA) and up to 80 % in rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive pJIA [5, 6]. The main treatment objectives in JIA are to control the pain and to prevent structural damage. Joint space narrowing (JSN), bone erosions and demineralization are radiographic findings shared between JIA and adult rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Changes specific to the paediatric population are early growth plate closure, epiphyseal deformity and growth asymmetry [7].

Conventional radiography (CR), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US) are the imaging modalities most often used to evaluate joint inflammation or structural damage [8]. MRI and US hold considerable promise but are still under evaluation in JIA. CR remains the most readily available imaging technique for detecting and monitoring structural damage. However, potential limitations of CR in JIA include the risk of radiation-induced harm to the patient, interpretation difficulties raised by skeletal immaturity, and the delayed development of structural joint damage. Furthermore, because JIA is rare, little is known about the potential effects of synthetic or biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) on structural joint damage [9,10,11]. Thus, whereas recommendations based on large studies are available for the radiographic assessment of chronic inflammatory joint disease in adults [12, 13], no similar guidelines have been developed for JIA. A task force was recently convened by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) – Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) to develop recommendations about imaging studies for diagnosing and managing JIA [14]. Although this undertaking acknowledged, for the first time, that an assessment of imaging studies in JIA was needed, the task force neither focussed on CR nor provided specific guidance for everyday practice.

We established a multidisciplinary task force to develop guidelines on the use of CR for the diagnosis and follow-up of each JIA subtype in everyday practice. Our project was supported by the French Society for Rheumatology (SFR), French Society for Paediatric Rheumatology and Internal Medicine (SOFREMIP), French Society for Paediatric and Prenatal Imaging (SFIPP), French Society for Radiology (SFR), and largest non-profit paediatric rheumatology patient organisation in France (KOURIR).

Methods

Field of research

We considered the following situations, at diagnosis and during follow-up, in each of the following five subtypes of JIA (oJIA, pJIA with and without RF and/or anti-citrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA), juvenile psoriatic arthritis (jPsA), and enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA)) Undifferentiated arthritis, as a heterogeneous subset related to one or several subtypes, and systemic JIA, having a peculiar articular course and structural prognosis, were left aside. Experts also focused on juvenile monoarthritis. Special attention was directed to the cervical spine, hip and temporo-mandibular joints (TMJs).

Recommendation development process

The task force comprised 16 JIA experts (eight rheumatologists, five paediatricians, two paediatric radiologists experienced in skeletal disease and one patient organisation representative). We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method [15, 16] for elaborating, evaluating, disseminating and implementing recommendations elaborated by the EULAR and the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) group [17, 18], and the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) process to frame the research questions.

We considered structural radiographic abnormalities: JSN, erosions, pseudo-joint space widening for sacro-iliac joint [19, 20] and ankylosis [12]. A research fellow (PM) assisted by two experts in systematic review methodology (CGV, methodologist; and VDP, convenor) performed a systematic literature review by searching PubMed, Scopus/Elsevier, and the Cochrane Library. Original articles including clinical trials, retrospective cohort studies, other retrospective studies, and case-control studies published between 1980 and December 2016 were identified. The following indexing was used: ‘juvenile idiopathic arthritis’ OR ‘juvenile rheumatoid arthritis’ OR ‘juvenile chronic arthritis’ OR ‘juvenile psoriatic arthritis’ OR ‘enthesitis-related arthritis’ OR ‘juvenile spondyloarthritis’ AND ‘radiography’ OR ‘X-ray’ (see Appendix 1 for details). The quality of evidence and grades of recommendation were determined according to the standards of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [21]. Recommendations were graded A to D depending on the level of the underlying evidence (from 1A to 4) [18].

The task force debated and formulated a preliminary set of recommendations based on the systematic literature review supplemented, when necessary, by their expert opinion. This set was then evaluated by a panel of 14 independent French-speaking experts. Modifications were debated by the task force. The final recommendations were then rated on a 10-point scale by the task force and independent panel through a Delphi process.

Results

Systematic literature review

Of the 118 publications identified by the literature search, 74 [5, 6, 9,10,11, 19, 20, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] original articles, as well as one abstract [89] and one online recommendation [90], were included (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Recommendations

The experts elaborated four overarching principles and 31 recommendations. Table 2 lists the recommendations.

Overarching principles

Radiation exposure was taken into account (principle B), according to French Society for Radiology recommendations [90] (Appendix 2). Much of the cartilage is still radio-transparent in children younger than 5 years of age. In this age group, the need for CR must be evaluated with great care (principle C) [91].

Other imaging modalities such as US and MRI are increasingly used in JIA. Although promising, they are not discussed herein. They will be the focus of specific recommendations (principle D).

Oligoarticular JIA (oJIA)

1. CR should not be performed routinely as a diagnostic investigation in oJIA. The literature review identified ten studies in which CR was performed, even in patients younger than 4 years. Among them, one focussed specifically on oJIA [35] and nine investigated several JIA subtypes but reported data separately for oJIA [6, 24, 27, 36,37,38, 40, 42, 43]. The usefulness of CR is limited by the incomplete ossification of the epiphyses, most notably in the youngest age groups [33]. Therefore, when the diagnosis is definitive, CR is not recommended.

2. and 3. During follow-up, CR should be performed on affected joint(s) that remain symptomatic after 3 months. By ‘symptomatic joints’*, we mean painful and/or swollen joints and/or joints that are limited in motion. In patients with persistently symptomatic* joints, the reiteration of CR during follow-up is at the discretion of the physician. Several studies showed evidence of radiographic progression early in the natural history of oJIA [24, 27, 35, 38].

4. In patients with clinically inactive disease (CID), CR should not be performed routinely. The diagnosis of CID relies on physician judgement, aided by validated tools [92,93,94]. No data are available on radiographic disease progression in clinically silent joints in patients with oJIA.

5. In patients with extended oJIA, the recommendations for pJIA should be applied. The number of affected joints is strongly associated with structural damage in oJIA [35].

6. In patients with structural damage, the selection and timing of specific imaging techniques to further assess the damaged joint during follow-up is guided by clinical considerations.

Joints with structural damage must undergo specific CR evaluations during the patient’s growth.

Polyarticular JIA (pJIA)

7. and 8. Routine CR of the wrists, hands and forefeet is strongly recommended at the diagnosis of polyarticular JIA with positive RF/ACPA. CR of other joints than wrists, hands and forefeet, is recommended at the diagnosis for symptomatic joints*only. Prospective studies were reviewed, with special attention to early pJIA. Erosions and JSN occurred preferentially at the hands, wrists and feet [11, 31, 43, 48,49,50,51], joints that were sometimes asymptomatic [31] CR at the diagnosis provides a reference for assessing disease progression. It is supported by ‘adult’ recommendations [13] for rheumatoid arthritis, which has a similar structural evolution.

9. and 10. In new-onset RF/ACPA-negative pJIA with adverse prognostic factors, CR at diagnosis should be performed as for RF/ACPA-positive pJIA. Box 1 lists the factors of adverse prognostic significance in pJIA [31, 44, 50, 51]. These factors are associated with a pattern of joint damage over time similar to that seen in RF/ACPA-positive pJIA [38].

Box 1: Factors of adverse prognostic significance in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (pJIA)

Early involvement of wrists Symmetric arthritis Distal, small-joint arthritis Elevated ESR/CRP Pre-existing radiographic abnormalities |

ESR, erthrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, serum C-reactive protein level

11. In new-onset, RF/ACPA-negative pJIA without adverse prognostic factors, at diagnosis, CR should be confined to symptomatic* joints. This recommendation is based on expert opinion.

12. In RF/ACPA-positive pJIA, CR of the hands, wrists and forefeet is strongly recommended 1 year after disease onset, and when transitioning from paediatric to adult healthcare. At other time points, the use of CR during follow-up is at the discretion of the physician. Prospective studies found evidence of joint damage even in asymptomatic joints [31]. Patients with long-standing disease had high prevalences of joint erosions (30–70 % in historical studies) [5, 28, 38, 40, 44, 48, 54], close to those in adults with RA [48]. In RA, joint destruction at asymptomatic sites is a major predictor of adverse outcomes [13, 95]. However, radiographic progression with erosions in asymptomatic joints is not well documented in JIA and may have been underestimated. In a study of 471 joints in 67 patients with polyarticular JIA, radiographs showed erosions at the hands and feet in 36 % and 39 % of cases, respectively [31]. Our literature review identified some data on the best times for CR. One study suggested a higher risk of radiographic progression within the first year after disease onset [51]. The experts felt that CR contributed to ease the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare [96].

13. Routine CR of other joints is not recommended. No data were found on which to base specific recommendations.

14. During the follow-up of RF/ACPA-negative pJIA with adverse prognostic factors, CR should be performed as for RF/ACPA-positive pJIA (see recommendation #12).

15. During the follow-up of RF/ACPA-negative pJIA without adverse prognostic factors, the use of CR is at the discretion of the physician. No scientific data were available on which to base specific recommendations.

16. and 17. CR can be repeated in patients who remain symptomatic* longer than 3 months. In patients with structural damage, the selection and timing of specific imaging techniques during follow-up is guided by clinical considerations. The experts emphasised the need for careful attention to joints with active disease. In prospective studies, the time interval separating CR assessments of the same joints ranged from 8 months to 24 years. The 3-month interval in this recommendation was based on expert opinion.

Enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA)

18. In patients with axial ERA, CR of the spine and hip joints should be performed only when needed for the differential diagnosis. Axial manifestations may arise at the spine, hips and sacro-iliac joints. A radiographic view specifically designed to assess the sacro-iliac joints is not recommended, as the results are not interpretable in skeletally immature patients and radiation exposure is significant [20]. In patients with axial inflammatory pain, MRI (for both sacro-iliac and hip joints) and US (for the hip joint) may be more relevant [67].

19. During the follow-up of axial ERA, CR should be considered only for the hip joints, depending on the clinical course and availability of US and/or MRI. ERA is associated with a high prevalence of hip joint arthritis [30, 56, 58,59,60]. MRI or US are non-irradiating methods capable of detecting hip joint effusion; in addition, MRI can detect bone oedema. Therefore, in the future, MRI and US may deserve consideration as first-line imaging techniques. CR, however, is appropriate for monitoring known structural damage and deformities.

20. and 21. CR is not recommended for multifocal enthesitis. In patients with isolated enthesitis, CR can be considered as a tool for establishing the differential diagnosis. When isolated enthesitis is suspected, CR may contribute to the differential diagnosis (e.g. with post-traumatic changes or osteochondritis); otherwise, CR is unhelpful for assessing peri-articular manifestations.

Psoriatic juvenile arthritis (jPsA)

22. No specific recommendation can be made about CR in juvenile psoriatic arthritis. Scientific data are scarce [62,63,64,65,66, 68]. The definition of this entity is still debated [68]. Traditionally, two subtypes are described, an axial inflammatory disease resembling axial ERA and a peripheral joint disease resembling oJIA [66].

23. Guidance may be taken from the recommendations above, depending on the clinical presentation, or from recommendations issued for adults.

Situations of specific interest

Monoarthritis

24. At the diagnosis of acute monoarthritis, CR of the involved joint should be performed, with two perpendicular views. The French Society for Radiology [90] strongly recommends CR of any site of focal bone pain in paediatric patients, with the goal of excluding a tumour, osteomyelitis, or a haematological malignancy [34, 97].

25. At the diagnosis of acute monoarthritis, comparative CR of the contralateral joint is unnecessary. Because cartilage thickness varies within individuals, comparison to the healthy contra-lateral joint is uninformative [26, 33].

Cervical spine

26. In patients with persistent neck pain related to JIA, MRI is preferable over CR.

27. When MRI is unavailable, CR is recommended only for the cervical spine and should consist only of a lateral view.

28. In patients with JIA who have neurological symptoms of spinal cord compression and neck pain, cervical MRI must be performed, on an emergency basis.

In a cohort study of oJIA, 2.4 % of patients had cervical spine damage at the diagnosis [35]. Cervical spine erosions and ankylosis are common in advanced pJIA [42, 71]. Evidence-based data are too scarce to recommend any specific pattern of radiological follow-up. Atlanto-axial diastasis may be normal in paediatric patients, and dynamic CR is therefore irrelevant. MRI is the most sensitive imaging technique, and is mandatory when spinal cord compression is suspected [98].

Temporomandibular joints

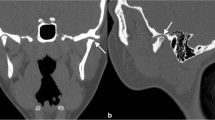

29. CR of the TMJs is not recommended when cross-sectional imaging is available.

TMJ damage is common in JIA, with the prevalence ranging across studies from 17 % to 87 % [73]. The TMJ cartilage is thin and condylar erosions therefore develop early. The panoramic radiograph is often normal at disease onset. Cross-sectional imaging offers better diagnostic performance. Imaging of the TMJs is not usually performed on a routine basis but is required in the event of pain, mouth-opening limitation or audible cracking of the TMJs [74, 76,77,78,79,80,81, 83, 84]. MRI is considered the best imaging technique, although distinguishing the normal appearance from abnormal changes can be challenging [99, 100]. Cone-beam computed tomography allows three-dimensional reconstructions [101]. The usefulness of US TMJ imaging is under debate [77, 102].

Hip joint

30. Routine CR of the hip joint is not recommended in patients with pJIA.

31. When CR of a symptomatic hip joint is performed, a single view should be obtained, i.e. either an antero-posterior view or a frog leg view.

In RF/ACPA-positive pJIA, hip joint damage is common [48] but CR of the hip joint is associated with a high level of ionising radiation exposure, so the hip is not among the joints for which routine CR is recommended .When available, MRI should be performed instead of, or in addition to, CR. If CR is performed, either an antero-posterior or a frog leg view is recommended, to visualise both hip joints and to allow the detection of bone erosions and/or avascular necrosis.

Discussion

CR is the most widely available imaging procedure worldwide. In paediatric patients, this advantage should be weighed against the heightened risks of radiation exposure and difficulty in interpreting joint radiographs before skeletal maturity is achieved. In addition, in JIA, radiographically visible joint damage takes time to develop, limiting the usefulness of CR. Specific recommendations about CR in paediatric patients are therefore needed, a fact that prompted the present work.

Obstacles to the development of recommendations about CR in JIA included the paucity of strong evidence about structural disease progression in JIA and the pooling of JIA subtypes in many studies. The low incidence of JIA contributes to explain the dearth of data. To maximise the usefulness of our recommendations to all physicians caring for patients with JIA, we focussed on CR and separated the five non-systemic, non-undifferentiated subtypes of JIA. Importantly, these recommendations are based not only on recently published data, but also, in many cases, on expert opinion, due to the paucity of paediatric studies. As a result, many of our recommendations are low grade, and in some cases obtaining guidance from recommendations for adults would seem to be the only option. However, the level of agreement among the multidisciplinary experts sitting on our panel was high.

Structural damage requires evaluation in JIA, especially in pJIA and extended oJIA, which carry the highest risk of adverse outcomes. In the treatment plans for pJIA developed by the CARRA, CR changes are considered an important outcome and their yearly assessment is suggested [55]. However, the risk associated with exposure to ionising radiation during CR is of major concern, as pointed out by the representative of the patient organisation during our study. Little evidence is available on which to base an objective quantification of this risk. Our experts considered that the risk was substantial for CR of the pelvis and lumbar spine but was too small at peripheral sites to constitute an argument against using CR. To minimise radiation exposure, the experts recommended having CR performed at centres with expertise in paediatric radioprotection.

Research is needed in a broad range of areas to fill the knowledge gaps we identified when developing our recommendations (Box 2). More specifically, most paediatric clinical trials failed to assess potential treatment effects on structural damage. Also, data on structural damage just before the transition to adult healthcare are needed, since treatment recommendations for adults are based on structural damage.

Box 2: Research agenda

- Follow-up of a cohort of patients with recent-onset RF/ACPA-positive polyarticular JIA, with annual CR for 10 years to identify predictors of structural joint damage - Comparison of radiographic disease progression in oligoarticular JIA in patients with and without antinuclear antibodies - Comparison of joint MRI, US, and CR as tools for detecting structural damage in patients younger than 5 years of age - Evaluation of joint damage at the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare in each JIA subtype - Improvement of the definition of juvenile psoriatic arthritis, to obtain homogeneous populations for studies of imaging techniques |

We considered neither MRI nor US, both of which are under evaluation in JIA. Both are non-irradiating, and US is also widely available and inexpensive, although it requires specific training. US is now performed almost routinely in adults with joint disease. In paediatric patients, however, differentiating normal from abnormal findings by MRI and US can be challenging [100, 103]. Furthermore, very few physicians are specifically trained in paediatric US. The OMERACT and Health-e-Child Radiology groups are currently working together to standardise MRI protocols and interpretation in JIA [104,105,106].

In conclusion, CR still appears relevant in many situations in patients with JIA. CR is a widely available and inexpensive investigation that has an acceptable safety profile and can provide essential information about the structural course of the disease. Until validation studies of other imaging techniques, such as MRI and US, are completed, CR will remain the investigation of reference for assessing structural joint damage in patients with JIA.

Abbreviations

- ACPA:

-

Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibody

- CR:

-

Conventional radiography

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying Antirheumatic drugs

- ERA:

-

Enthesitis-related arthritis

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- ILAR:

-

International League Against Rheumatism

- JIA:

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- jPsA:

-

Juvenile psoriatic arthritis

- JSN:

-

Joint space narrowing

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- oJIA:

-

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- OMERACT:

-

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology

- PReS:

-

Paediatric Rheumatology European Society

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

- pJIA:

-

Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- SFIPP:

-

French Society for Paediatric and Prenatal Imaging

- SFR:

-

French Society for Radiology

- SFR:

-

French Society for Rheumatology

- sJIA:

-

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- SLR:

-

Systematic literature review

- SOFREMIP:

-

French Society for Paediatric Rheumatology and Internal Medicine

- TMJ:

-

Temporo-mandibular joint

- US:

-

Ultrasound

References

Prakken B, Albani S, Martini A (2011) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet Lond Engl 377:2138–2149

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P et al (2004) International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 31:390–392

Martini A (2012) It is time to rethink juvenile idiopathic arthritis classification and nomenclature. Ann Rheum Dis 71:1437–1439

Deslandre C (2016) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Definition and classification. Arch Pediatr 23(4):437–41

Mason T, Reed AM, Nelson AM, Thomas KB (2005) Radiographic progression in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis 64:491–493

Ravelli A, Martini A (2003) Early predictors of outcome in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 21:S89–S93

Southwood T (2008) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: clinically relevant imaging in diagnosis and monitoring. Pediatr Radiol 38(Suppl 3):S395–S402

Breton S, Jousse-Joulin S, Finel E et al (2012) Imaging approaches for evaluating peripheral joint abnormalities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 41:698–711

Nielsen S, Ruperto N, Gerloni V et al (2008) Preliminary evidence that etanercept may reduce radiographic progression in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 26:688–692

Harel L, Wagner-Weiner L, Poznanski AK et al (1993) Effects of methotrexate on radiologic progression in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 36:1370–1374

Ravelli A, Viola S, Ramenghi B et al (1998) Radiologic progression in patients with juvenile chronic arthritis treated with methotrexate. J Pediatr 133:262–265

Devauchelle-Pensec V, Josseaume T, Samjee I et al (2008) Ability of oblique foot radiographs to detect erosions in early arthritis: results in the ESPOIR cohort. Arthritis Rheum 59:1729–1734

Gaujoux-Viala C, Gossec L, Cantagrel A et al (2014) Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology for managing rheumatoid arthritis. Jt Bone Spine Rev Rhum 81:287–297

Colebatch AN, Edwards CJ, Østergaard M et al (2013) EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging of the joints in the clinical management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72:804–814

Brożek JL, Akl EA, Compalati E et al (2011) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines part 3 of 3. The GRADE approach to developing recommendations. Allergy 66:588–595

GRADE, GRADE home. Available via http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/. Accessed 19 May 2016

Dougados M, Betteridge N, Burmester GR et al (2004) EULAR standardised operating procedures for the elaboration, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation of recommendations endorsed by the EULAR standing committees. Ann Rheum Dis 63:1172–1176

van der Heijde D, Aletaha D, Carmona L et al (2015) 2014 Update of the EULAR standardised operating procedures for EULAR-endorsed recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 74:8–13

Stoll ML, Bhore R, Dempsey-Robertson M, Punaro M (2010) Spondyloarthritis in a pediatric population: risk factors for sacroiliitis. J Rheumatol 37:2402–2408

Pagnini I, Savelli S, Matucci-Cerinic M et al (2010) Early predictors of juvenile sacroiliitis in enthesitis-related arthritis. J Rheumatol 37:2395–2401

Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Levels of Evidence (2009). Available via http://www.cebm.net. Acced 19th May 2016

Chan MO, Petty RE, Guzman J, ReACCh-Out Investigators (2016) A Family History of Psoriasis in a First-degree Relative in Children with JIA: to Include or Exclude? J Rheumatol 43:944–947

Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Schiappapietra B, Martini A (2015) The conundrum of juvenile psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33:S40–S43

Ravelli A, Varnier GC, Oliveira S et al (2011) Antinuclear antibody-positive patients should be grouped as a separate category in the classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63:267–275

Kavanaugh A, van der Heijde D, Beutler A et al (2016) Radiographic Progression of Patients With Psoriatic Arthritis Who Achieve Minimal Disease Activity in Response to Golimumab Therapy: Results Through 5 Years of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Arthritis Care Res 68:267–274

Poznanski AK (1991) Useful measurements in the evaluation of hand radiographs. Hand Clin 7:21–36

Lipinska J, Brózik H, Stanczyk J, Smolewska E (2012) Anticitrullinated protein antibodies and radiological progression in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 39:1078–1087

Selvaag AM, Flatø B, Dale K et al (2006) Radiographic and clinical outcome in early juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile spondyloarthropathy: a 3-year prospective study. J Rheumatol 33:1382–1391

van Rossum MAJ, Boers M, Zwinderman AH et al (2005) Development of a standardized method of assessment of radiographs and radiographic change in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: introduction of the Dijkstra composite score. Arthritis Rheum 52:2865–2872

Flatø B, Smerdel A, Johnston V et al (2002) The influence of patient characteristics, disease variables, and HLA alleles on the development of radiographically evident sacroiliitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 46:986–994

van Rossum MAJ, Zwinderman AH, Boers M et al (2003) Radiologic features in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a first step in the development of a standardized assessment method. Arthritis Rheum 48:507–515

Rodriguez-Lozano A-L, Giancane G, Pignataro R et al (2014) Agreement among musculoskeletal pediatric specialists in the assessment of radiographic joint damage in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 66:34–39

Rossi F, Di Dia F, Galipò O et al (2006) Use of the Sharp and Larsen scoring methods in the assessment of radiographic progression in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 55:717–723

Tafaghodi F, Aghighi Y, Rokni Yazdi H et al (2009) Predictive plain X-ray findings in distinguishing early stage acute lymphoblastic leukemia from juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 28:1253–1258

Guillaume S, Prieur AM, Coste J, Job-Deslandre C (2000) Long-term outcome and prognosis in oligoarticular-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 43:1858–1865

Al-Matar MJ, Petty RE, Tucker LB et al (2002) The early pattern of joint involvement predicts disease progression in children with oligoarticular (pauciarticular) juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 46:2708–2715

Oen K, Malleson PN, Cabral DA et al (2003) Early predictors of longterm outcome in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: subset-specific correlations. J Rheumatol 30:585–593

Oen K, Reed M, Malleson PN et al (2003) Radiologic outcome and its relationship to functional disability in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 30:832–840

Oen K (2002) Long-term outcomes and predictors of outcomes for patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 16:347–360

Bowyer SL, Roettcher PA, Higgins GC et al (2003) Health status of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis at 1 and 5 years after diagnosis. J Rheumatol 30:394–400

Bertilsson L, Andersson-Gäre B, Fasth A, Forsblad-d’Elia H (2012) A 5-year prospective population-based study of juvenile chronic arthritis: onset, disease process, and outcome. Scand J Rheumatol 41:379–382

Bertilsson L, Andersson-Gäre B, Fasth A et al (2013) Disease course, outcome, and predictors of outcome in a population-based juvenile chronic arthritis cohort followed for 17 years. J Rheumatol 40:715–724

Giancane G, Pederzoli S, Norambuena X et al (2014) Frequency of radiographic damage and progression in individual joints in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 66:27–33

Gilliam BE, Chauhan AK, Low JM, Moore TL (2008) Measurement of biomarkers in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients and their significant association with disease severity: a comparative study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 26:492–497

Doria AS, de Castro CC, Kiss MHB et al (2003) Inter- and intrareader variability in the interpretation of two radiographic classification systems for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatr Radiol 33:673–681

Maldonado-Cocco JA, García-Morteo O, Spindler AJ et al (1980) Carpal ankylosis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 23:1251–1255

Habib HM, Mosaad YM, Youssef HM (2008) Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Immunol Investig 37:849–857

Elhai M, Bazeli R, Freire V et al (2013) Radiological peripheral involvement in a cohort of patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis at adulthood. J Rheumatol 40:520–527

Mason T, Reed AM, Nelson AM et al (2002) Frequency of abnormal hand and wrist radiographs at time of diagnosis of polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 29:2214–2218

Flatø B, Lien G, Smerdel A et al (2003) Prognostic factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study revealing early predictors and outcome after 14.9 years. J Rheumatol 30:386–393

Magni-Manzoni S, Rossi F, Pistorio A et al (2003) Prognostic factors for radiographic progression, radiographic damage, and disability in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48:3509–3517

Ozawa R, Inaba Y, Mori M et al (2012) Definitive differences in laboratory and radiological characteristics between two subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: systemic arthritis and polyarthritis. Mod Rheumatol Jpn Rheum Assoc 22:558–564

Omar A, Abo-Elyoun I, Hussein H et al (2013) Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): correlations with disease activity and severity of joint damage (a multicenter trial). Jt Bone Spine Rev Rhum 80:38–43

Williams RA, Ansell BM (1985) Radiological findings in seropositive juvenile chronic arthritis (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) with particular reference to progression. Ann Rheum Dis 44:685–693

Ringold S, Weiss PF, Colbert RA et al (2014) Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus treatment plans for new-onset polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 66:1063–1072

Chen H-A, Chen C-H, Liao H-T et al (2012) Clinical, functional, and radiographic differences among juvenile-onset, adult-onset, and late-onset ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 39:1013–1018

Rostom S, Amine B, Bensabbah R et al (2008) Hip involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 27:791–794

Flatø B, Hoffmann-Vold A-M, Reiff A et al (2006) Long-term outcome and prognostic factors in enthesitis-related arthritis: a case-control study. Arthritis Rheum 54:3573–3582

Jadon DR, Ramanan AV, Sengupta R (2013) Juvenile versus adult-onset ankylosing spondylitis -- clinical, radiographic, and social outcomes. a systematic review. J Rheumatol 40:1797–1805

Lin Y-C, Liang T-H, Chen W-S, Lin H-Y (2009) Differences between juvenile-onset ankylosing spondylitis and adult-onset ankylosing spondylitis. J Chin Med Assoc JCMA 72:573–580

Jaremko JL, Liu L, Winn NJ et al (2014) Diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging and radiography in juvenile spondyloarthritis: evaluation of the sacroiliac joints in controls and affected subjects. J Rheumatol 41:963–970

Butbul YA, Tyrrell PN, Schneider R et al (2009) Comparison of patients with juvenile psoriatic arthritis and nonpsoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: how different are they? J Rheumatol 36:2033–2041

Flatø B, Lien G, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Vinje O (2009) Juvenile psoriatic arthritis: longterm outcome and differentiation from other subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 36:642–650

Huemer C, Malleson PN, Cabral DA et al (2002) Patterns of joint involvement at onset differentiate oligoarticular juvenile psoriatic arthritis from pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 29:1531–1535

Stoll ML, Nigrovic PA, Gotte AC, Punaro M (2011) Clinical comparison of early-onset psoriatic and non-psoriatic oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 29:582–588

Stoll ML, Punaro M (2011) Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a tale of two subgroups. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:437–443

Weiss PF, Xiao R, Biko DM, Chauvin NA (2016) Assessment of Sacroiliitis at Diagnosis of Juvenile Spondyloarthritis by Radiography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Clinical Examination. Arthritis Care Res 68:187–194

Tsitsami E, Bozzola E, Magni-Manzoni S et al (2003) Positive family history of psoriasis does not affect the clinical expression and course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients with oligoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 49:488–493

Elhai M, Wipff J, Bazeli R et al (2013) Radiological cervical spine involvement in young adults with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl 52:267–275

Laiho K, Savolainen A, Kautiainen H et al (2002) The cervical spine in juvenile chronic arthritis. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc 2:89–94

Endén K, Laiho K, Kautiainen H et al (2009) Subaxial cervical vertebrae in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis--something special? Jt Bone Spine Rev Rhum 76:519–523

Kjellberg H, Pavlou I (2011) Changes in the cervical spine of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis evaluated with lateral cephalometric radiographs: a case control study. Angle Orthod 81:447–452

Twilt M, Mobers SMLM, Arends LR et al (2004) Temporomandibular involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 31:1418–1422

Abramowicz S, Simon LE, Susarla HK et al (2014) Are panoramic radiographs predictive of temporomandibular joint synovitis in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis? J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 72:1063–1069

Abramowicz S, Susarla HK, Kim S, Kaban LB (2013) Physical findings associated with active temporomandibular joint inflammation in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 71:1683–1687

Arvidsson LZ, Smith H-J, Flatø B, Larheim TA (2010) Temporomandibular joint findings in adults with long-standing juvenile idiopathic arthritis: CT and MR imaging assessment. Radiology 256:191–200

Müller L, Kellenberger CJ, Cannizzaro E et al (2009) Early diagnosis of temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a pilot study comparing clinical examination and ultrasound to magnetic resonance imaging. Rheumatol Oxf Engl 48:680–685

Cedströmer A-L, Andlin-Sobocki A, Berntson L et al (2013) Temporomandibular signs, symptoms, joint alterations and disease activity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis - an observational study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 11:37

Górska A, Przystupa W, Rutkowska-Sak L et al (2014) Temporomandibular joint dysfunction and disorders in the development of the mandible in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis - preliminary study. Adv Clin Exp Med Off Organ Wroclaw Med Univ 23:797–804

Koos B, Gassling V, Bott S et al (2014) Pathological changes in the TMJ and the length of the ramus in patients with confirmed juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg 42:1802–1807

Koos B, Twilt M, Kyank U et al (2014) Reliability of clinical symptoms in diagnosing temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 41:1871–1877

Billiau AD, Hu Y, Verdonck A et al (2007) Temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: prevalence, clinical and radiological signs, and relation to dentofacial morphology. J Rheumatol 34:1925–1933

Helenius LMJ, Tervahartiala P, Helenius I et al (2006) Clinical, radiographic and MRI findings of the temporomandibular joint in patients with different rheumatic diseases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 35:983–989

Pedersen TK, Küseler A, Gelineck J, Herlin T (2008) A prospective study of magnetic resonance and radiographic imaging in relation to symptoms and clinical findings of the temporomandibular joint in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 35:1668–1675

Cannizzaro E, Schroeder S, Müller LM et al (2011) Temporomandibular joint involvement in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 38:510–515

Kristensen KD, Stoustrup P, Küseler A et al (2016) Clinical predictors of temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 45:717–732

Colebatch-Bourn AN, Edwards CJ, Collado P et al (2015) EULAR-PReS points to consider for the use of imaging in the diagnosis and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1946–1957

Jadon DR, Sengupta R, Nightingale A et al (2016) Axial Disease in Psoriatic Arthritis study: defining the clinical and radiographic phenotype of psoriatic spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209853

Ravelli. (2014) A11: Assessment of Radiographic Progression in Patients With Polyarticular-Course Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Treated With Tocilizumab: 2-Year Data From CHERISH - Arthritis & Rheumatology - Wiley Online Library. Available via http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/enhanced/doi/10.1002/art.38422. Accessed 19 May 2016

French Society for Radiology, French Society for Nuclear Medicine (2013) Guide du bon usage des examens d’imagerie médicale. Available via http://www.sfrnet.org/sfr/professionnels/5-referentiels-bonnes-pratiques/guides/guide-bon-usage-examens-imagerie-medicale/index.phtml. Accessed 30 Mar 2016

Laor T, Clarke JP, Yin H (2016) Development of the long bones in the hands and feet of children: radiographic and MR imaging correlation. Pediatr Radiol 46:551–561

Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Huang B et al (2011) American College of Rheumatology provisional criteria for defining clinical inactive disease in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 63:929–936

McErlane F, Beresford MW, Baildam EM et al (2013) Validity of a three-variable Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score in children with new-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72:1983–1988

Consolaro A, Ruperto N, Bazso A et al (2009) Development and validation of a composite disease activity score for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 61:658–666

Brown AK, Quinn MA, Karim Z et al (2006) Presence of significant synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-induced clinical remission: evidence from an imaging study may explain structural progression. Arthritis Rheum 54:3761–3773

Foster HE, Minden K, Clemente D et al (2016) EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210112

Rayen BS, Chapman A (2005) Monoarthritis; remember to ask the child. Arch Dis Child 90:69

Joaquim AF, Ghizoni E, Tedeschi H et al (2015) Radiological evaluation of cervical spine involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Neurosurg Focus 38:E4

Kottke R, Saurenmann RK, Schneider MM et al (2015) Contrast-enhanced MRI of the temporomandibular joint: findings in children without juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Acta Radiol Stockh Swed 56:1145–1152

Ma GMY, Amirabadi A, Inarejos E et al (2015) MRI thresholds for discrimination between normal and mild temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 13:53

Farronato G, Garagiola U, Carletti V et al (2010) Change in condylar and mandibular morphology in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Cone Beam volumetric imaging. Minerva Stomatol 59:519–534

Melchiorre D, Falcini F, Kaloudi O et al (2010) Sonographic evaluation of the temporomandibular joints in juvenile idiopathic arthritis(). J Ultrasound 13:34–37

Ording Muller L-S, Boavida P, Avenarius D et al (2013) MRI of the wrist in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: erosions or normal variants? A prospective case-control study. Pediatr Radiol 43:785–795

Nusman CM, Rosendahl K, Maas M (2016) MRI Protocol for the Assessment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis of the Wrist: Recommendations from the OMERACT MRI in JIA Working Group and Health-e-Child. J Rheumatol 43:1257–1258

Nusman CM, Ording Muller L-S, Hemke R et al (2016) Current Status of Efforts on Standardizing Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Report from the OMERACT MRI in JIA Working Group and Health-e-Child. J Rheumatol 43:239–244

Roth J, Ravagnani V, Backhaus M et al (2016) Preliminary definitions for the sonographic features of synovitis in children. Arthritis Care Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23130

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge : Dr Bouchra Amine (Salé, Morocco), Prof. Nathalie Boutry (Lille, France), Prof. Rolando Cimaz (Florence, Italy), Prof. Bernard Combe (Montpellier, France), Dr Véronique Despert (Rennes, France), M William Fahy (KOURIR, non-profit organisation, France), Dr Laurence Goumy (Angers, France), Prof. Michael Hofer (Lausanne, Switzerland), Dr Laëtitia Houx (Brest, France), Dr Sylvie Jean (Rennes, France), Dr Valérie Merzoug (Paris, France), Mme Céline Obert (KOURIR), Prof. Michel Panuel (Marseille, France), Prof. Samira Rostom (Salé, Morocco), Prof. Jean Sibilia (Strasbourg, France); and Pr Hubert Ducou Le Pointe, (French Society for Pediatric Radiology).

Funding

This study has received funding by the Société Française de Rhumatologie (French Society for Rheumatology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Prof Valérie Devauchelle-Pensec.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies.

Statistics and biometry

No complex statistical methods, were necessary for this paper.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was not required; the methodology entirely relies on literature review and expert opinion.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required because no human subjects were involved.

Methodology

• Retrospective

• Literature review, and expert consensus seeking through a Delphi process

• Performed at one institution

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Appendix 2

(DOC 36 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marteau, P., Adamsbaum, C., Rossi-Semerano, L. et al. Conventional radiography in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Joint recommendations from the French societies for rheumatology, radiology and paediatric rheumatology. Eur Radiol 28, 3963–3976 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5304-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5304-7