Abstract

Objective

To investigate arterial spin labeling (ASL)-MRI for the early diagnosis of and differentiation between the two most common types of presenile dementia: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and for distinguishing age-related from pathological perfusion changes.

Methods

Thirteen AD and 19 FTD patients, and 25 age-matched older and 22 younger controls underwent 3D pseudo-continuous ASL-MRI at 3 T. Gray matter (GM) volume and cerebral blood flow (CBF), corrected for partial volume effects, were quantified in the entire supratentorial cortex and in 10 GM regions. Sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic performance were evaluated in regions showing significant CBF differences between patient groups or between patients and older controls.

Results

AD compared with FTD patients had hypoperfusion in the posterior cingulate cortex, differentiating these with a diagnostic performance of 74 %. Compared to older controls, FTD patients showed hypoperfusion in the anterior cingulate cortex, whereas AD patients showed a more widespread regional hypoperfusion as well as atrophy. Regional atrophy was not different between AD and FTD. Diagnostic performance of ASL to differentiate AD or FTD from controls was good (78-85 %). Older controls showed global hypoperfusion compared to young controls.

Conclusion

ASL-MRI contributes to early diagnosis of and differentiation between presenile AD and FTD.

Key Points

• ASL-MRI facilitates differentiation of early Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia.

• Posterior cingulate perfusion is lower in Alzheimer’s disease than frontotemporal dementia.

• Compared to controls, Alzheimer’s disease patients show hypoperfusion in multiple regions.

• Compared to controls, frontotemporal dementia patients show focal anterior cingulate hypoperfusion.

• Global decreased perfusion in older adults differs from hypoperfusion in dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although less prevalent, presenile dementia (age of onset ≤65 years) comprises a substantial subset of dementia patients [1]. Compared to late-onset dementia, it more often has an atypical presentation and more progressive disease course. Early diagnosis of presenile dementia remains difficult as different etiologies are hard to distinguish. Presenile Alzheimer’s disease (AD) more often has a non-amnestic presentation than late-onset AD [2]. Additionally, non-neurological causes of cognitive dysfunction are more prevalent in younger patients and may mimic neurodegenerative disorders, particularly obscuring differentiation between psychiatric disease and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [3]. Another large subset of young patients presents with primary progressive aphasia (PPA), in which the underlying pathology – AD or FTD – is often unclear [4].

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) often shows distinctive brain atrophy only in later stages AD and FTD [5]. Early diagnosis requires techniques that detect early brain changes, such as fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). FDG-PET visualizes hypometabolism in temporo-parietal regions, posterior cingulate, and precuneus in AD, while FTD affects the prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and anterior temporal cortex [6]. Arterial spin labeling (ASL)-MRI, measuring brain perfusion, has been proposed as an alternative as it is noninvasive and easily added to routine diagnostic MRI protocols, whereas FDG-PET has limited availability and relatively high costs [7]. Hypoperfusion measured with ASL is consistent with PET in advanced AD and FTD, indicating that ASL could contribute to differential diagnosis [8, 9]. The use of ASL in the earliest stages of dementia is being increasingly studied [10, 11], but little is known about ASL findings in the early stage of presenile dementia, when diagnosis is often still uncertain. To reliably assess regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) changes in such patients, we also need to determine normal - regional - CBF variability, as this is substantial in healthy young adults [12].

The aim of this study was to investigate ASL-MRI for the early diagnosis of and differentiation between the two most common types of presenile dementia: AD and FTD [2]. We also investigated age-related CBF changes to distinguish pathological from physiological changes in regional perfusion.

Methods

Participants

Newly presenting patients visiting our outpatient memory clinic between January 2011 and September 2013, aged 45 to 70 years, and with a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 20 (indicating mild dementia) were prospectively considered for inclusion. All patients underwent neurological and neuropsychological examination as part of their routine diagnostic work up. We consecutively included patients with a diagnosis of possible or probable AD or FTD. In addition, patients were included with PPA in which the underlying aetiology can be either AD or FTD. The reference standard was a nosological diagnosis of AD or FTD by consensus according to the McKhann [13] and Rascovsky [14] criteria, or AD or FTD underlying PPA [4]. Diagnosis was established either at baseline (initial visit), or after follow-up when diagnosis at baseline was uncertain, and verified independently by two experienced neurologists. Conventional structural MRI was assessed as part of the diagnostic process and simultaneously assessed for exclusion criteria, ASL-MRI was not. Patients with psychiatric or neurological disorders other than dementia were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were normal pressure hydrocephalus, Huntington’s disease, cerebral vascular disease, alcohol abuse, brain tumour, epilepsy or encephalitis.

Healthy young (18 to 40 years) and older (45 to 70 years) controls were recruited through advertisement, and older controls also from their patient peers. Data from these young participants were previously reported in a reproducibility study of ASL [15]. Both control groups were matched for gender, and older controls for age with the patients. A researcher screened all participants, who were included only when there was no history of neurological or psychiatric disease, and no contraindications for MRI. Older controls were administered the MMSE to assess global cognitive functioning.

The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee. All participants gave written informed consent.

Image acquisition

All participants were examined at 3 T (Discovery MR750 system, GE Healthcare, USA). Perfusion was measured with state-of-the-art [16] whole brain 3D pseudo-continuous ASL (p-CASL) (background-suppressed, post-labeling delay 1525 ms, labeling duration 1450 ms, echo time (TE) 10.5 ms, repetition time (TR) 4632 ms, interleaved FSE stack-of-spiral readout of 512 sampling points on eight spirals, isotropic resolution 3.3 mm in a field of view (FOV) of 240 mm, 36 axial slices, number of excitations 3, acquisition time 4.29 min). The labeling plane was positioned 9 cm below the anterior commissure-posterior commissure line. A high resolution 3-D fast spoiled gradient-echo T1-weighted (T1w) image (FOV 240 mm, TR/TE/inversion time 7.9/3.06/450 ms, ASSET factor 2, matrix 240*240, and slice thickness 1 mm, acquisition time 4.41 min) was acquired for anatomical reference.

Image data processing

The data were processed according to methods described previously [17] to obtain partial volume effect corrected CBF values from gray matter (GM) only.

Tissue segmentation

Gray matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid maps were obtained from the T1w image using the unified tissue segmentation method [18] of SPM8 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, London, UK). GM volumes were computed from the GM map. CBF was analyzed in GM only.

ASL post-processing

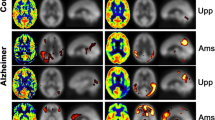

The ASL imaging dataset consisted of two images, a perfusion-weighted image (PWI) and a proton density image (PD), that were required for CBF calculation [16]. CBF maps from representative patients are shown in Figure 1. The GM map derived from the T1w image was rigidly registered with the PD image for each participant (Elastix registration software [19]). Then GM maps were transformed to ASL image space to enable partial volume (PV) correction. PV effects were corrected in PWI and PD images using local linear regression within a 3D kernel based on tissue maps [20]. The PV-corrected ASL images were quantified as CBF maps using the single-compartment model [16] as implemented by the scanner manufacturer. Finally CBF maps were transformed to T1w image space for further analysis.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF in ml/100 g GM/min) maps for a representative AD (left column) and FTD patient (right column). The top row shows their skull-stripped CBF map, the bottom row shows their colour-coded CBF maps overlaid on the structural T1w images. Hypoperfusion is prominent in the PCC (thick arrows) in AD compared to FTD. Also note the global and more extensive hypoperfusion in AD compared to the focal hypoperfusion in the ACC in FTD (thin arrows). CBF: cerebral blood flow; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; T1w: T1 weighted; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; ACC: anterior cingulate cortex

ROI labeling

For each participant, regions of interest (ROIs) were defined using a multi-atlas approach. This involved the registration of 30 labeled T1w images, each containing 83 ROIs [21, 22], to the participants’ T1w images. The labels of the 30 atlas images were fused using a majority voting algorithm to obtain a final ROI labeling [23]. Registration to the participants’ nonuniformity-corrected T1w images [24] were performed with a rigid, affine, and a non-rigid B-spline transformation model consecutively. For this registration, both the participants’ and the labeled T1w images were masked using the Brain Extraction Tool [25].

Region selection

CBF was assessed per participant globally in the entire supratentorial cortex, and regionally in ten predefined cortical regions relevant for dementia, based on previously reported PET-findings in AD and FTD [26–28] (Table 1). Mean GM CBF and volumes in these regions were extracted for the left and right hemisphere separately and subsequently reported as an average of the bilateral regions. GM volumes were reported as percentage of the total intracranial volume (% ICV).

Data analysis

Gender differences across patient and control groups were examined using chi-square tests (p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05) was used to examine age and MMSE differences across AD and FTD patients and older controls; and to compare global and regional GM CBF and volume across the patient and control groups. Variation within and between groups was visualized with a boxplot.

Sensitivity and specificity of regional CBF were evaluated for both patient groups using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. We examined regions known to be affected in dementia that showed significant differences between FTD or AD patients and older controls. Regions significantly different between FTD and AD patients were selected to investigate their performance in differentiating the patient groups. Diagnostic performance was expressed by areas under the curve (AUC) with 95 % confidence intervals. For the regions with the highest AUCs, optimal cut-off points were determined to discriminate between the examined groups by locating the cut-off point where the distance from maximum sensitivity and specificity was minimal. Distance was calculated for each observed cut-off point using the equation: distance = √[(1 – sensitivity)2 + (1 – specificity)2]. Based on these cut-off points, false positives (FPs) and false negatives (FNs) were determined to explore whether age, gender, MMSE or PPA variant affected misclassification.

Statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20.0 (New York, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

One hundred participants were included in our study: 53 dementia patients, 22 healthy young adult and 25 healthy older participants (Table 2). Post hoc, 21 of the 53 included patients were excluded due to diagnoses other than AD or FTD during follow-up (7), lack of progression (4), low data quality (4), or because of incomplete imaging data (6). Median follow-up was 1.2 years (range 2 weeks – 2.8 years).

Gender was not different across groups (χ2 (3, n = 79) = 1.822, p > .05). Age was not different between AD and FTD patients and older controls (F(2,54) = 0.886, p > .05). MMSE was different across the patient groups and older controls (F(2,53) = 13.476, p < .05): both patient groups had lower scores compared to older controls, but not compared to each other (Table 2). Due to language deficits, two patients with PPA had MMSE scores of <20. Their full neuropsychological examination indicated only moderate impairment in all cognitive domains except for language, affecting the MMSE score. Their data were therefore retained in the analysis.

Global perfusion and volume changes

Mean CBF of the supratentorial cortex (Table 3, Fig. 2) was not different between AD and FTD. Compared with older controls, global perfusion was lower in AD, but not in FTD. Older controls showed lower global perfusion than young controls. Mean GM volume was not different between AD and FTD, but was lower in both AD and FTD compared to controls (Table 3).

Regional cerebral blood flow (CBF in ml/100 g GM/min) in FTD and AD patients and older and young controls. The central box represents values from lower to upper quartile (25-75 percentile), the middle line represents the median, and vertical bars extend from minimum to maximum values. Markers outside the bars indicate extreme values (sphere: value ≥ 1.5 x interquartile range (IQR); asterisk: value ≥ 3 x IQR. ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; CBF: cerebral blood flow; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; GM: gray matter; MTL: medial temporal lobe; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; PFC: prefrontal cortex; ROI: region of interest

Regional perfusion and volume changes

Changes related to dementia

Of the regions affected by dementia, the PCC showed lower CBF in AD than FTD (Table 3, Fig. 2). Compared to older controls, CBF was lower in all these regions in AD, but only in the ACC in FTD. GM volume was not different between AD and FTD, but was lower in AD compared to controls in all regions affected in dementia except the ACC and medial PFC. FTD had lower volumes in all regions except the thalamus (Table 3).

Of the regions initially unaffected by dementia, CBF in and volume of the precentral gyrus showed differences neither between AD and FTD nor between each of the patient groups and older controls. Mean CBF and GM volume in the occipital lobe and calcarine cortex was lower in AD than in older controls, but did not differ between FTD and controls.

Age-related changes

Mean CBF in all ROIs was lower in older than in young controls (Table 3, Fig. 2). Mean GM volumes (Table 3) were lower in all ROIs except the medial temporal lobe (MTL) (Table 3). In both control groups, CBF was relatively highest in the PCC and lowest in the occipital lobe.

Diagnostic performance of ASL in dementia

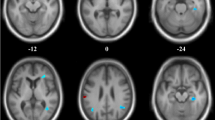

CBF was lower in AD than FTD in the PCC (Table 3), in which ROC analysis yielded an AUC of 0.741 (Table 4). The optimal cut-off point differentiated AD from FTD with 69 % sensitivity and 68 % specificity (Fig. 3a).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and optimal cut-off points and associated sensitivity and specificity for GM CBF in regions of interest that show significant differences between AD and FTD patients (a), AD patients and older controls (b) and FTD patients and older controls (c). ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; GM: gray matter; MTL: medial temporal lobe; OC: older controls; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; PFC: prefrontal cortex

As all regions showed lower CBF in AD than controls (Table 3), these were all examined (Table 4). The precuneus performed best (AUC: 0.849) and differentiated AD patients from controls with 77 % sensitivity and 76 % specificity (Fig. 3b).

FTD had lower CBF than controls in the ACC (Table 3), in which ROC analysis yielded an AUC of 0.775 (Table 4) and differentiated FTD from controls with 79 % sensitivity and 76 % specificity (Fig. 3c).

Overall, misclassification of participants was not explained by age, gender, PPA variant, or MMSE, as these variables deviated less than 1 standard deviation in FP and FN cases compared to true positive and negative cases. However, male controls were labeled as diseased more than female controls: in differentiating AD from healthy controls, five out of six FP cases were male and in differentiating FTD from controls six out of six.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that ASL-MRI contributes to early differential diagnosis of presenile dementia. Compared to FTD patients, AD patients showed hypoperfusion in the PCC. Differentiation between the patient groups based on this finding had a diagnostic performance of 74 %. Compared to age-matched controls, FTD patients showed focal hypoperfusion in the ACC, whereas AD patients showed a more extensive hypoperfusion. These CBF changes discriminated FTD and AD patients well from age-matched controls (diagnostic performances of 78 % and 85 %, respectively). Finally, we observed that CBF was globally reduced with increased age, which should be distinguished from the pathological hypoperfusion in dementia. Atrophy and hypoperfusion corresponded frequently in AD, but not in FTD. Crucially, gray matter volume was not different between AD and FTD, indicating that these cannot be distinguished based on regional atrophy at this stage and in this patient population. This indicates that ASL-MRI provides contributing information for the differential diagnosis.

The observed lower CBF in the PCC in AD than in FTD is in agreement with previous studies [8, 9, 29]. Notably, we found CBF measurement in the PCC performing reasonably (74 %) to differentiate presenile AD from FTD, which may thus serve as a diagnostic marker to differentiate these diseases at an early stage. Previous studies reported additional differential regional hypoperfusion in the precuneus and temporo-parietal cortex in AD, and in the ACC and frontal cortex in FTD [8, 9, 29]. Our AD patients had lower CBF than FTD patients in all regions, including in those typically lower in FTD, which may have obscured differences between the patient groups. Nevertheless, the extensive CBF changes are consistent with the literature [30–32], and with the finding that in early FTD that the extent of atrophy exceeds that of hypoperfusion, while in AD these are similar [29].

This discrepancy in hypoperfusion may also explain why CBF changes in FTD patients were limited to the ACC. Additional hypoperfusion in FTD has been reported in the temporal lobe, medial PFC, and thalamus [29], whereas hypometabolism on PET is generally limited to frontal regions in early-stage fluent PPA and behavioral-variant FTD (bv-FTD) [33]. The localized ACC hypoperfusion may, thus, be due to the disease still being at an early stage. Furthermore, focal ACC neuronal loss has been associated with tau pathology [34] which is correlated with both bv-FTD and PPA variants [35], suggesting our FTD sample comprises predominantly patients with tau pathology.

CBF was globally decreased in AD, but of note is that a global CBF decrease does not necessarily indicate dementia. Compared to young controls, older controls also show globally decreased CBF. This is concordant with previous studies [36] and suggests that CBF reduces with aging. To our knowledge, no longitudinal ASL studies exist to verify this, but a longitudinal PET study supports this conclusion [37]. Closer examination of the global CBF changes showed that relative regional differences are generally preserved with age but also with neurodegeneration. For instance, despite the disproportionate widespread hypoperfusion in AD, and being most severely affected in AD and FTD, the PCC and ACC remain among the regions with the highest CBF. This intrinsically high regional CBF may obscure subtle neurodegenerative changes, and, thus, requires quantitative measurement rather than visual inspection.

This study has some limitations. First, our ROI definition was somewhat different from functional definition of ROIs by the literature. The structural ROIs used here may explain some unexpected findings, such as hypoperfusion in the calcarine cortex in AD. Our structural ROI also included the lingual gyrus and cuneus, which have shown hypoperfusion in AD [30] and may thus have affected this entire region’s CBF. Nevertheless, our results are generally consistent with previous findings. We specifically chose this multi-subject atlas [21, 22] because its automated ROI definition is more robust than single-subject atlases. Second, the cross-sectional design does not allow for generalization of results to aging as a process. Still, the results provide insight in physiological CBF changes associated with higher age, compared to pathological CBF changes in higher age with concomitant dementia. Third, our sample is rather heterogeneous, comprising not only patients with AD or FTD phenotype, but also with PPA with AD or FTD as underlying pathology. Patient misclassification seemed not be affected by PPA variant, nor by gender, age, or MMSE. The heterogeneity of our sample on the other hand illustrates precisely the complexity of this patient population and the difficulty inherent to nosological diagnosis as a reference standard. A degree of uncertainty always remains, although it decreases as the disease progresses. Nevertheless, like the majority of in vivo dementia studies, our study relies on a reference standard that implies classification by means of the best available evidence. In addition, we report group effects, which may not necessarily generalize to individual patients. These issues may challenge the diagnostic value of ASL. However, we collected ASL data at a time point in the diagnostic process when diagnosis was not yet definitive. Only after follow-up, diagnosis was established. This shows that with ASL diagnosis can be made earlier than with routine clinical criteria, even at the individual patient level. Future studies should focus on validation of group results for individual diagnosis. Finally, the current results were obtained using a single scanner, while CBF measurement may not be robust across imaging centers. Inter-scanner and inter-vendor differences should be taken into account in patient studies [15] to reliably interpret quantitative CBF changes indicative of dementia and establish cut-off values.

In conclusion, we show that ASL-MRI can contribute to early diagnosis of presenile dementia and differentiate between AD and FTD where structural MRI does not. Hypoperfusion in the precuneus, ACC, and PCC may serve as quantitative diagnostic markers for respectively presenile AD, FTD, and their differentiation. Widespread hypoperfusion is seen in early stage presenile AD, but needs to be distinguished from a physiological CBF decrease in the older population. The clinical implementation of ASL should eventually be based on data of multicenter studies. This will help to determine and validate reference values and further improve diagnostic performance of differential diagnosis in early stage presenile dementia.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

anterior cingulate cortex

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- ASL:

-

arterial spin labeling

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- CBF:

-

cerebral blood flow

- FDG-PET:

-

fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography

- FN:

-

false negative

- FOV:

-

field of view

- FP:

-

false positive

- FTD:

-

frontotemporal dementia

- FSE:

-

fast spin echo

- GM:

-

gray matter

- MMSE:

-

Mini Mental State Examination

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- MTL:

-

medial temporal lobe

- PCC:

-

posterior cingulate cortex

- PD:

-

proton density

- PFC:

-

prefrontal cortex

- PPA:

-

primary progressive aphasia

- PV:

-

partial volume

- PWI:

-

perfusion-weighted image

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- ROI:

-

region of interest

- T1w:

-

T1 weighted

- TE:

-

echo time

- TR:

-

repetition time

References

van der Flier WM, Scheltens P (2005) Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 76(Suppl 5):v2–7

Koedam EL, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YA (2010) Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer's disease: More than age alone. J Alzheimers Dis 19:1401–1408

Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD (2010) The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol 9:793–806

Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S et al (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76:1006–1014

Frisoni GB, Fox NC, Jack CR Jr, Scheltens P, Thompson PM (2010) The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 6:67–77

Ishii K (2013) PET approaches for diagnosis of dementia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 35:2030–2038

McMahon PM, Araki SS, Sandberg EA, Neumann PJ, Gazelle GS (2003) Cost-effectiveness of PET in the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Radiology 228:515–522

Hu WT, Wang Z, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Detre JA, Grossman M (2010) Distinct cerebral perfusion patterns in FTLD and AD. Neurology 75:881–888

Du AT, Jahng GH, Hayasaka S et al (2006) Hypoperfusion in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease by arterial spin labeling MRI. Neurology 67:1215–1220

Wang Z (2014) Characterizing early Alzheimer's disease and disease progression using hippocampal volume and arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI. J Alzheimers Dis 42(Suppl 4):S495–502

Wierenga CE, Hays CC, Zlatar ZZ (2014) Cerebral blood flow measured by arterial spin labeling MRI as a preclinical marker of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 42(Suppl 4):S411–9

Pfefferbaum A, Chanraud S, Pitel AL et al (2010) Volumetric cerebral perfusion imaging in healthy adults: Regional distribution, laterality, and repeatability of pulsed continuous arterial spin labeling (PCASL). Psychiatry Res 182:266–73

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H et al (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the national institute on aging-Alzheimer's association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 7:263–269

Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D et al (2011) Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134:2456–2477

Mutsaerts HJ, Steketee RME, Heijtel DF et al (2014) Inter-vendor reproducibility of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling at 3 tesla. PLoS ONE 9, e104108

Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X et al (2015) Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the european consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 73:102–116

Bron EE, Steketee RME, Houston GC et al (2014) Diagnostic classification of arterial spin labeling and structural MRI in presenile early stage dementia. Hum Brain Mapp 35:4916–4931

Ashburner J, Friston KJ (2005) Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26:839–851

Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim JP (2010) Elastix: A toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 29:196–205

Asllani I, Borogovac A, Brown TR (2008) Regression algorithm correcting for partial volume effects in arterial spin labeling MRI. Magn Reson Med 60:1362–1371

Hammers A, Allom R, Koepp MJ et al (2003) Three-dimensional maximum probability atlas of the human brain, with particular reference to the temporal lobe. Hum Brain Mapp 19:224–247

Gousias IS, Rueckert D, Heckemann RA et al (2008) Automatic segmentation of brain MRIs of 2-year-olds into 83 regions of interest. Neuroimage 40:672–684

Heckemann RA, Hajnal JV, Aljabar P, Rueckert D, Hammers A (2006) Automatic anatomical brain MRI segmentation combining label propagation and decision fusion. Neuroimage 33:115–126

Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA et al (2010) N4ITK: Improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 29:1310–1320

Smith SM (2002) Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 17:143–155

Foster NL, Heidebrink JL, Clark CM et al (2007) FDG-PET improves accuracy in distinguishing frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Brain 130:2616–2635

Ibach B, Poljansky S, Marienhagen J, Sommer M, Manner P, Hajak G (2004) Contrasting metabolic impairment in frontotemporal degeneration and early onset Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage 23:739–743

Santens P, De Bleecker J, Goethals P et al (2001) Differential regional cerebral uptake of (18)F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia at initial diagnosis. Eur Neurol 45:19–27

Zhang Y, Schuff N, Ching C et al (2011) Joint assessment of structural, perfusion, and diffusion MRI in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2011:546871

Asllani I, Habeck C, Scarmeas N, Borogovac A, Brown TR, Stern Y (2008) Multivariate and univariate analysis of continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28:725–736

Chen Y, Wolk DA, Reddin JS et al (2011) Voxel-level comparison of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI and FDG-PET in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 77:1977–1985

Binnewijzend MA, Kuijer JP, van der Flier WM et al (2014) Distinct perfusion patterns in Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia and dementia with lewy bodies. Eur Radiol 24:2326–2333

Diehl J, Grimmer T, Drzezga A, Riemenschneider M, Förstl H, Kurz A (2004) Cerebral metabolic patterns at early stages of frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. A PET study. Neurobiol Aging 25:1051–1056

Tan RH, Pok K, Wong S, Brooks D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ (2013) The pathogenesis of cingulate atrophy in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 1:1–30

Chare L, Hodges JR, Leyton CE et al (2014) New criteria for frontotemporal dementia syndromes: Clinical and pathological diagnostic implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85:865–870

Chen JJ, Rosas HD, Salat DH (2011) Age-associated reductions in cerebral blood flow are independent from regional atrophy. Neuroimage 55:468–478

Thambisetty M, Beason-Held L, An Y, Kraut MA, Resnick SM (2010) APOE epsilon4 genotype and longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in normal aging. Arch Neurol 67:93–98

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Dr. Marion Smits. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. This study has received funding by the Coolsingel Foundation (Rotterdam, NL) and by a personal fellowship granted by the Erasmus University Rotterdam. No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study. Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in Mutsaerts HJ, Steketee RME, Heijtel DF, et al. Inter-vendor reproducibility of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling at 3 tesla. PLoS One 2014;9:e104108. Methodology: prospective; diagnostic or prognostic study; performed at one institution

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Steketee, R.M.E., Bron, E.E., Meijboom, R. et al. Early-stage differentiation between presenile Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia using arterial spin labeling MRI. Eur Radiol 26, 244–253 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3789-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3789-x