Abstract

Behçet’s Disease (BD) can be correlated with sleep impairment and fatigue, resulting in low quality of life (QoL); however, a comprehensive evaluation of this issue is still missing. We performed a systematic literature review (SLR) of existing evidence in literature regarding sleep quality in BD. Fifteen papers were included in the SLR. Two domains were mainly considered: global sleep characteristics (i) and the identification of specific sleep disorders (ii) in BD patients. From our analysis, it was found that patients affected by BD scored significantly higher Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) compared to controls. Four papers out of 15 (27%) studied the relationship between sleep disturbance in BD and disease activity and with regards to disease activity measures, BD-Current Activity Form was adopted in all papers, followed by Behçet’s Disease Severity (BDS) score, genital ulcer severity score and oral ulcer severity score. Poor sleep quality showed a positive correlation with active disease in 3 out of 4 studies. Six papers reported significant differences between BD patients with and without sleep disturbances regarding specific disease manifestations. Notably, arthritis and genital ulcers were found to be more severe when the PSQI score increased. Our work demonstrated lower quality of sleep in BD patients when compared to the general population, both as altered sleep parameters and higher incidence of specific sleep disorders. A global clinical patient evaluation should thereby include sleep assessment through the creation and adoption of disease-specific and accessible tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Behçet’s Disease (BD) is a chronic systemic vasculitis which may affect small to medium vessels. It is characterized by a relapsing–remitting course and most frequently by muco-cutaneous, ocular and articular involvement [1].

Lifestyle and daily activities of BD patients are greatly affected by the complexity of the possible clinical profiles, resulting in a significant association with impaired quality of life (QoL) [2]. Sleep quality is an important item of QoL, and it is known to be commonly poorer in patients affected by rheumatic diseases when compared to the general population [3]. Moreover, previous studies have hypothesized a bidirectional association between sleep disorders and autoimmunity, although pathophysiological mechanisms have not been elucidated [4, 5].

Similarly to other systemic autoimmune diseases, BD can be correlated with sleep impairment and fatigue, resulting in low QoL [3]; however, a comprehensive evaluation of this issue is still missing. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of existing evidence in literature regarding sleep quality in BD.

Methods

A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to analyze existing evidence about sleep quality in BD patients. The results of our systematic review were reported according to the PRISMA statement.

Search strategy

A search was performed in MEDLINE via PubMed to identify studies published until October 2021, using the following terms [“Behcet Syndrome” AND “Sleep” OR “Sleep Medicine Specialty” OR “Sleep Phase Chronotherapy” OR “REM Sleep Parasomnias” OR “Sleep-Wake Transition Disorders” OR “Sleep Arousal Disorders” OR “Sleep Disorders, Intrinsic” OR “Sleep Paralysis” OR “REM Sleep Behavior Disorder” OR “Sleep Bruxism” OR “Sleep Apnea, Central” OR “Sleep Apnea, Obstructive” OR “Sleep Disorders, Circadian Rhythm” OR “Sleep, REM” OR “Sleep Stages” OR “Sleep Wake Disorders” OR “Sleep Deprivation” OR “Sleep Apnea Syndromes” OR “Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders” OR “Sleep, Slow-Wave” OR “Sleep Latency” OR “Sleep Hygiene” OR “Dyssomnias” OR “Parasomnias” OR “Nocturnal Myoclonus Syndrome” OR “Night Terrors” OR “Nocturnal Paroxysmal Dystonia” OR “Somnambulism” OR “Polysomnography” OR “Narcolepsy” OR “Irresistible sleepiness, cataplexy and onset of sleep in desynchronized phase”] in all fields. Two independent reviewers have performed an examination of the references listed in the articles to identify further additional publications.

Study selection/inclusion and exclusion criteria

Exclusion and inclusion criteria were established in advance. Publications were considered appropriate if they assessed sleep quality in BD patients, and if the language of publication was English. Exclusion criteria concerned case reports, animal studies, conference abstracts and review articles, articles not in English, articles not assessing sleep in BD.

Participants/population

Studies were included if they investigated sleep quality in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of BD (according to the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease [6] or according to a clinical diagnosis of BD). Studies were excluded if they involved patients without a confirmed diagnosis of BD.

Data extraction

Title and abstracts of the identified articles were evaluated by two independent reviewers (N.I., F.D.C.) to rule out duplicates and check if inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. Full-text screening of the selected publications was independently performed by the two reviewers and meetings were held to agree on the final list of studies to be included. Any disagreement was solved through consensus among the two reviewers and in case of unresolved disagreements senior researchers were invited to participate in the discussion and take the final decision.

A data extraction form into a pre-designed excel sheet was developed to collect the following variables from the studies selected: author, journal, year of publication, type of study, study aim, number of patients involved in the study and their gender/age, number of healthy controls, sleep quality evaluation, tools used to evaluate sleep quality, specific sleep disorders taken into account, tools used to evaluate the specific sleep disorders, correlation with specific disease manifestations, correlation with BD activity, tools used to evaluate BD activity, main results obtained.

Results

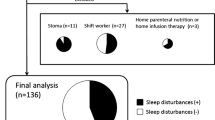

As of November 22nd, 2021, 60 records were extracted by the literature research on the PubMed database (semantic: 39; MeSH 21). These records were reduced to 51 after duplicates removal and were then screened for title and abstract evaluation. Seventeen papers were eligible for a full-text evaluation, which eventually produced 15 papers to be included in our systematic review (Fig. 1).

Among the 15 papers included (Table 1), 13 were cross-sectional studies and 2 were retrospective cohort studies.

Overall, data about 121.415 BD patients were collected (84.603 males (69.7%), 36.812 females (30.3%)) with a range of age of between 18 and 65 years. No studies included patients under the age of 18.

The two most explored domains were the overall quality of sleep and the specific sleep disorders in BD, evaluated by administering one or more sleep-related non-disease-specific questionnaires and/or by performing a polysomnography (PSG).

More specifically, 8 papers [1, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12] out of 15 (53%) exclusively assessed global sleep quality and sleep characteristics in BD patients, by adopting the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire in 7 [1, 6,7,8,9,10, 12] out of 8 papers (87, 5%) and the Mini Sleep Questionnaire (MSQ) in 1 [11] (12, 5%). On the other hand, 5 [5, 13,14,15,16] papers out of 15 (33%) exclusively evaluated the frequency of a specific sleep disorder in BD, that is Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) in 2/5 papers [14, 15] and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSAS) in 3/5 [5, 13, 16] papers. The Berlin Questionnaire (BQ) [13], the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [14], RLS identification-form and the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group-Rating Scale (IRLSSG-RS) [15] were performed by one paper each, respectively to identify the risk of OSAS in a BD cohort, to examine subjective sleep quality in BD patients suffering from RLS, to make RLS diagnosis and to evaluate RLS severity. On the other hand, PSG was performed in 2 works [5, 16] out of 5 (40%) to explore OSAS. Finally, two papers [3, 17] (13%) investigated both the global sleep characteristics in a BD cohort along with the evaluation of the presence of RLS and OSAS, overall employing PSQI, ESS and PSG.

From our analysis it was found that patients affected by BD scored significantly higher PSQI compared to controls, with medium scores of PSQI ranging from 6.42 to 9.4 (value obtained from the ranges of PSQI score available in nine papers). In addition, Yazmalar et al. [1] and Tascilar et al. [3] analyzed each PSQI item, and the score of subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep disorder and daily dysfunction overall appeared significantly worse in BD cohorts compared to controls. Regarding the PSG-based sleep quality evaluation, longer sleep onset time, longer nREM stages, longer wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) and increased respiratory disturbance index (RDI) were the most often detected objective sleep alterations in BD patients.

Four papers out of 15 (27%) studied the relationship between sleep disturbance in BD and disease activity [3, 6,7,8]. With regards to disease activity measures, Behçet’s Disease Current Activity Form (BDCAF) was adopted in all papers, followed by Behçet’s Disease Severity (BDS) score [3], genital ulcer severity score (GUSS) and oral ulcer severity score (OUSS) [6]. Poor sleep quality showed a positive correlation with active disease in 3 out of 4 studies [6, 7, 9], whereas Tascilar et al. [3] observed no difference between active and inactive patients in terms of any sleep disorders and PSG alterations. On the other hand, in the analysis of total PSQI and subsection PSQI by Lee et al. [8], only daytime dysfunction was significantly higher in patients with higher BDCAF score.

Furthermore, six papers [1, 3, 6, 13,14,15] reported significant differences between BD patients with and without sleep disturbances with regard to specific disease manifestations. Notably, arthritis and genital ulcers were found to be more severe when the PSQI score increased [6]. Also, RLS and OSAS respectively showed higher incidence in BD patients with central nervous system (CNS) involvement [17] and in BD patients with superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) [13]. Tascilar et al. [3] evaluated the polysomnographic macrostructure of sleep according to BDCAF subsections, reporting that genital ulcerations increased WASO and that oculopathy index was negatively correlated with total sleep time (TST) and time in bed (TIB). Only one study [14] found no differences between BD patients and controls with regard to disease manifestations.

No studies comparing frequency of sleep disturbances among cohorts of patients affected by BD and other autoimmune diseases were found. Nonetheless, in the study by Yeh et al. [5] incidence of OSAS was also measured in a population of patients affected by Sjogren’s syndrome (SS), showing higher rates of OSAS when compared to healthy controls (HCs).

Discussion

Quality of sleep is known to be impaired in patients affected by systemic autoimmune diseases [3], but a systematic and comprehensive evidence was not yet available about the correlation between sleep disturbances and BD.

In our systematic review, two domains were mainly considered: global sleep characteristics (i) and the identification of specific sleep disorders (ii) in patients affected by BD.

(i) Global Sleep Assessment. Regarding the overall assessment of sleep characteristics in BD, two studies measured quantitative sleep parameters performing polysomnographic evaluation. In comparison with HCs, PSG revealed a longer sleep onset time, longer nREM stages, longer WASO, increased RDI, and significantly lower SEI (sleep efficiency index) and SCI (sleep continuity index). These results seem consistent with the difficulty in falling asleep, short sleep, lessened sleep efficiency, day-time sleepiness and fatigue, complained by BD patients in real life. Sleep features were also assessed by sleep-related non-disease-specific questionnaires. The most frequently adopted questionnaire in the publications included in our systematic review was PSQI. In almost all the studies reviewed, BD patients scored statistically significant higher PSQI values compared to HCs. One exception was the study by Toprak et al. [13], in which the statistical significance for PSQI was achieved only for the cohort of patients with both BD and fibromyalgia (FM) diagnoses. In fact, FM is a condition causing chronic widespread pain and diffuse tenderness, and it is associated to impaired neural signaling causing hyperalgesia and allodynia [18], contributing to sleep disturbances. Moreover, BD also shows frequent neurological involvement with consequent higher rates of central sensitization (CS) and neuropathic pain syndrome (NPS), which correlate with higher PSQI scores as described in the studies by Evcik et al. [9] and Ayar et al. [11]. Therefore, also considering that the incidence of FM may reach high rates in BD population [19, 20], the single contribution of such concomitant clinical conditions in inducing impaired sleep quality in BD patients still remains arguable.

(ii) Sleep disorders. In the articles included in the present work, the only two specific sleep disorders taken into consideration were OSAS and RLS. OSAS is a common condition in autoimmune diseases, as previously reported in several studies [16, 21]. Our review observed comparable data also in BD. Four studies [3, 5, 16, 17] reported statistically significant higher rates of OSAS in BD patients compared to HC, and this correlation was interpreted as a result of the chronic inflammatory state induced by the disease involvement of upper airways. Intriguingly, in the study by Chen et al. [17] it was suggested that conversely OSAS may be a risk factor for the development of autoimmune diseases including BD. According to that, primitive OSAS can contribute to systemic inflammation through the stimulation of circulating proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. This observation supports the presence of a bidirectional relationship between OSAS and BD, based on the existing evidence of elevated levels of various serum inflammatory cytokines in both conditions. Some evidence also suggests that higher circulating rates of inflammatory cytokines interfere with neuroendocrine activity and central nervous transmission, clarifying sleep impairment and neurological disorders in inflammatory conditions [9]. RLS was analyzed by four studies [3, 14, 15, 17] included in the present review, which unanimously showed significantly higher incidence of RLS (between 15 and 30%) in BD patients when compared to HCs. These studies disagree on the role played by disease involvement and severity in the occurrence of RLS. In fact, Önalan et al. [16] found a statistically significant difference in RLS incidence between NBD and non-NBD patients, indicating a possible connection with neurological involvement. The other studies observed no difference with regard to the clinical features of BD. Ediz et al. [15] and Tascilar et al. [3] respectively proposed iron-deficiency due to gastrointestinal inflammation and chronic pain secondary to CNS dopaminergic system dysfunction as possible hypotheses of the physio-pathological relationship between BD and RLS.

Future perspectives/unmet needs. Our review points out the impact and high frequency of sleep impairment in BD patients. Poor sleep quality definitely represents an additional impairment in BD patients and in their quality of life, which is already impacted by several factors such as sexuality [23], psychological burden [24, 25]. Consequently, patients’ examination should also include the assessment of sleep quality, usually performed through the administration of questionnaires. In the studies we included, five different questionnaires were adopted. These sleep-related questionnaires are not specific for BD nor validated for it, so they might not provide a comprehensive and accurate overview on sleep features in such patients. Secondarily, these tools differ in structure and scoring system, making results not comparable. Hence, a BD-specific questionnaire would be desirable. In addition to the tools based on the patient’s point of view, sleep characteristics should also be evaluated by objective instrumental tests. PSG examines quantitative and comparable parameters of sleep, but it is burdened by scarce feasibility and reliability since it is conducted in a non-domestic environment. An instrumental tool to perform the monitoring of sleep in real-life conditions should thus be preferable. One last point highlighted by our review is the discrepancy of the results about the correlation between sleep quality and disease activity and involvement. For a better understanding of this issue, prospective longitudinal studies accounting sleep assessment as part of the patient follow-up are required, with the aim of examining sleep features in different phases of disease. Results from these studies might offer an interesting starting point to observe whether and how sleep alterations respond to BD therapy and empower patients in addressing quality of sleep during the consultations with their specialist [26] as part of their healthcare decision-making process.

Conclusions

The present review of the literature demonstrates lower quality of sleep in BD patients when compared to the general population, both as altered sleep parameters and higher incidence of specific sleep disorders. A global clinical patient evaluation should thereby include sleep assessment through the creation and adoption of disease-specific and accessible tests.

Future prospective studies on BD patients cohorts should be performed to investigate the correlation between disease activity and sleep quality during follow-up, also with the aim of assessing quality of life in BD by adopting a more comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach that can definitely also contribute to improve the clinical and therapeutic management.

References

Yazmalar L, Batmaz İ, Sarıyıldız MA, Yıldız M, Uçmak D, Türkçü F, Akdeniz D, Sula B, Çevik R (2017) Sleep quality in patients with Behçet’s disease. Int J Rheum Dis 20(12):2062–2069. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12459 (Epub 2014 Sep 8)

Bodur H, Borman P, Ozdemir Y, Atan C, Kural G (2006) Quality of life and life satisfaction in patients with Behcet’s disease: relationship with disease activity. Clin Rheumatol 25:329–333

Tascilar NF, Tekin NS, Ankarali H, Sezer T, Atik L, Emre U, Duysak S, Cinar F (2012) Sleep disorders in Behçet’s disease, and their relationship with fatigue and quality of life. J Sleep Res 21(3):281–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00976.x (Epub 2011 Oct 17)

Abad VC, Sarinas PS, Guilleminault C (2008) Sleep and rheumatologic disorders. Sleep Med Rev 12(3):211–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.09.001

Yeh TC, Chen WS, Chang YS, Lin YC, Huang YH, Tsai CY, Chen JH, Chang CC (2020) Risk of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with Sjögren syndrome and Behçet’s disease: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Sleep Breath 24(3):1199–1205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01953-w (Epub 2020 Jan 3)

The International Study Group for Behcet’s Disease (1992) Evaluation of diagnostic (‘classification’) criteria in Behcet’s disease–towards internationally agreed criteria. Br J Rheumatol 31:299–308

Senusi AA, Liu J, Bevec D, Bergmeier LA, Stanford M, Kidd D, Jawad A, Higgins S, Fortune F (2018) Why are Behçet’s disease patients always exhausted? Clin Exp Rheumatol 36(6):53–62 (Epub 2018 Oct 5)

Lee J, Kim SS, Jeong HJ, Son CN, Kim JM, Cho YW, Kim SH (2017) Association of sleep quality in Behcet disease with disease activity, depression, and quality of life in Korean population. Korean J Intern Med 32(2):352–359. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.367 (Epub 2017 Feb 16)

Evcik D, Dogan SK, Ay S, Cuzdan N, Guven M, Gurler A, Boyvat A (2013) Does Behcet’s disease associate with neuropathic pain syndrome and impaired well-being? Clin Rheumatol 32(1):33–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2086-1 (Epub 2012 Sep 22)

Koca I, Savas E, Ozturk ZA, Tutoglu A, Boyaci A, Alkan S, Kisacik B, Onat AM (2015) The relationship between disease activity and depression and sleep quality in Behçet’s disease patients. Clin Rheumatol 34(7):1259–1263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2632-0 (Epub 2014 May 10)

Ayar K, Ökmen BM, Altan L, Öztürk EK (2021) Central sensitization and its relationship with health profile in Behçet’s disease. Mod Rheumatol 31(2):474–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2020.1780076 (Epub 2020 Jul 6)

Masoumi M, Tabaraii R, Shakiba S, Shakeri M, Smiley A (2020) Association of lifestyle elements with self-rated wellness and health status in patients with Behcet’s disease. BMC Rheumatol 27(4):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-020-00148-1

Toprak M, Erden M, Alpaycı M, Ediz L, Yazmalar L, Hız Ö, Tekeoğlu İ (2017) The frequency and effect of fibromyalgia in patients with Behçet’s disease. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 63(2):160–164. https://doi.org/10.5606/tftrd.2017.291

Gokturk A, Esatoglu SN, Atahan E, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H, Seyahi E (2019) Increased frequency of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in Behçet’s syndrome patients with superior vena cava syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 37(Suppl 121 6):132–136

Ediz L, Hiz O, Toprak M, Ceylan MF, Yazmalar L, Gulcu E (2011) Restless legs syndrome in Behçet’s disease. J Int Med Res 39(3):759–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/147323001103900307

Önalan A, Matur Z, Pehlıvan M, Akman G (2018) Restless legs syndrome in patients with Behçet’s disease and multiple sclerosis: prevalence, associated conditions and clinical features. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 57(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2017.20562

Chen WS, Chang YS, Chang CC, Chang DM, Chen YH, Tsai CY, Chen JH (2016) Management and risk reduction of rheumatoid arthritis in individuals with obstructive sleep apnea: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Sleep 39(10):1883–1890. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.6174

Uygunoğlu U, Benbir G, Saip S, Kaynak H, Siva A (2014) A polysomnographic and clinical study of sleep disorders in patients with Behçet and neuro-Behçet syndrome. Eur Neurol 71(3–4):115–119. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355277 (Epub 2014 Jan 21)

Jobanputra C, Richey RH, Nair J, Moots RJ, Goebel A (2017) Fibromyalgia in Behçet’s disease: a narrative review. Br J Pain 11(2):97–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463717701393 (Epub 2017 Mar 22)

Yavuz S, Fresko I, Hamuryudan V, Yurdakul S, Yazici H (1998) Fibromyalgia in Behçet’s syndrome. J Rheumatol 25:2219–2220

Melikoglu M, Melikoglu MA (2013) The prevalence of fibromyalgia in patients with Behçet’s disease and its relation with disease activity. Rheumatol Int 33:1219–1222

Kang JH, Lin HC (2012) Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of autoimmune diseases: a longitudinal population-based study. Sleep Med 13:583–588

Talarico R, Elefante E, Parma A, Taponeco F, Simoncini T, Mosca M (2020) Sexual dysfunction in Behçet’s syndrome. Rheumatol Int 40(1):9–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04455-w (Epub 2019 Oct 8)

Talarico R, Palagini L, d’Ascanio A, Elefante E, Ferrari C, Stagnaro C, Tani C, Gemignani A, Mauri M, Bombardieri S, Mosca M (2015) Epidemiology and management of neuropsychiatric disorders in Behçet’s syndrome. CNS Drugs 29(3):189–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-015-0228-0

Talarico R, Palagini L, Elefante E, Ferro F, Tani C, Gemignani A, Bombardieri S, Mosca M (2018) Behçet’s syndrome and psychiatric involvement: is it a primary or secondary feature of the disease? Clin Exp Rheumatol 36(6 suppl 115):125–128 (Epub 2018 Dec 13)

Marinello D, Di Cianni F, Del Bianco A, Mattioli I, Sota J, Cantarini L, Emmi G, Leccese P, Lopalco G, Mosca M, Padula A, Piga M, Salvarani C, Taruscio D, Talarico R (2021) Empowering patients in the therapeutic decision-making process: a glance into Behçet’s syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne) 13(8):769870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.769870

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NI: acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work, final approval of the version to be published. Email italiano.nazzareno@gmail.com. FC: acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work, final approval of the version to be published. Email dicianni.fe@gmail.com. DM: drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. Email diana.marinello@gmail.com. EE: revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. Email: elena.elefante87@gmail.com. MM: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. Email: marta.mosca@unipi.it. RT: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; interpretation of data for the work, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Email: sara.talarico76@gmail.com.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Italiano, N., Di Cianni, F., Marinello, D. et al. Sleep quality in Behçet’s disease: a systematic literature review. Rheumatol Int 43, 1–19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05218-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05218-w