Abstract

The purpose of this study was to use the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to identify physical and psychosocial problems associated with symptoms of Behçet’s disease (BD) in Japanese patients. Thirty patients with BD were interviewed in a pilot study using the “ICF Checklist”, and a team of medical experts selected categories related to physical and psychosocial aspects of BD. To identify specific physical and psychosocial problems of Japanese patients with BD, 100 new patients were interviewed using the selected categories. Among the 128 categories in the original ICF Checklist, 80 categories were identified as impaired, and another 12 ICF categories were added based on expert discussion of patients input. The number of problem categories was significantly greater in patients with BD with eye involvement and fatigue (eye involvement, 25.7 categories; fatigue, 25.2 categories; both P < 0.001). Specifically, patients with eye involvement had more difficulties with problems in daily life, such as writing (odds ratio 4.2), understanding such nonverbal messages as gestures and facial expressions (13.7), moving (5.7), walking in intense sunlight and bright light (17.6), and patients with fatigue had more difficulties with climate problems such as symptoms getting worse at the turn of the seasons or on cold days (2.5), compared to those without these symptoms. This study demonstrated that support focusing not only on physical symptoms but on other aspects of life as well is necessary for patients with BD, particularly patients with eye involvement and fatigue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a chronic inflammatory disease that leads to recurrent aphthous ulcers of the mouth and genitalia, relapsing uveitis, and skin lesions such as erythema nodosum [1]. Because BD is a chronic multisystem disorder, it may cause various problems in daily life or lead to functional disability [2, 3]. In particular, the presence of arthritis and eye involvement decreases quality of life (QOL) in patients with BD [4]. Because of the complex symptoms of BD, patients with this disorder tend to have both physical and psychosocial problems in their daily lives.

In a cross-sectional, postal survey using the EuroQol 5 Dimension, Bernabé et al. [2] reported that joint problems had the strongest impact on QOL in patients with BD. In addition, in a cross-sectional study using the Short-form 36 (SF-36), Ertam et al. [4] showed that the presence of arthritis and eye involvement significantly affected QOL in patients with BD.

There are also reports on the relationship between BD and psychiatric symptoms [5, 6]. Talarico et al. reported a higher frequency of psychiatric disorders in patients with BD compared with other chronic diseases. In particular, they demonstrated that bipolar disorders, major depressive unipolar disorder, and insomnia were common in patients diagnosed with BD [5]. In addition, in a review article, they showed that anxiety and depression are common psychiatric disorders in patients with BD, and in some cases, precede the onset of the typical symptoms of BD [6].

Thus, patients with BD who have both physical and mental symptoms are likely to develop problems in daily life associated with the BD. Medical staff need to accurately assess the problems of patients with BD. Appropriate indices to comprehensively evaluate the disease impact and QOL of patients with BD are needed.

Previous studies have reported on the relationship between various symptoms of BD and QOL [2,3,4], but few reports on the relationship between various symptoms in BD and specific physical and psychosocial problems have been published. Therefore, there are unknown factors that lead to a decline in QOL in patients with BD. Because these patients need comprehensive support from a bio-psycho-social perspective, intervention by a multi-disciplinary team is needed. Several important physical and psychosocial problems should be understood to support the care of patients with BD.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [7] is a tool used to identify multi-disciplinary aspects of a disease and provide a comprehensive understanding of patients. It was developed in a world-wide consensus process and endorsed by the World Health Assembly as a part of the World Health Organization Family of International Classifications in May 2001. In addition to evaluating patients’ physical and psychosocial problems, the ICF can be used by medical teams as a planning guide for treatment and care. The ICF provides a framework and classification from the perspective of patients at both the individual and population levels [8]. It is composed of approximately 1,600 categories relevant to functioning and health, currently divided into 3 of 4 components: “Body functions and structures”, “Activities and participation”, and “Environmental factors.” The fourth component, “Personal factors”, has not yet been classified. Each of these components was translated into Japanese by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and a Japanese edition was published in 2002.

The purpose of this study was to use the ICF to identify physical and psychosocial problems based on symptoms of BD in Japanese patients.

Materials and methods

Pilot study

Patients

An initial 30 outpatients with BD diagnosed based on the International Criteria for BD [9] and visited the hospital regularly were studied from October 2014 to April 2015 at Teikyo University Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. Patients were excluded if they had severe dementia.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The Teikyo University Review Board approved this study (Approval Number 14–044).

Instrument

The ICF Checklist Version 2.1α, Clinician Form [10], represents a selection of 128 ICF categories from the complete ICF classification system. Of the 128 checklist categories, 32 belong to the “Body functions” component, 16 to the “Body structures” component, 48 to the “Activities and participation” component, and 32 to the “Environmental factors” component. This is a practical tool to elicit and record information on individuals’ functioning and disability.

Data collection and procedures

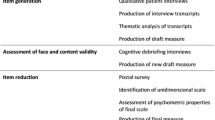

Using the ICF Checklist (Online Appendix), patients were interviewed and asked whether they had experienced any of the problems in each category of the checklist since BD was diagnosed. Patients answered each question either “yes” or “no.” All categories in which at least 1 patient reported a problem were selected as “problem categories”. At least 1 of 30 patients reported a problem in 80 categories of the ICF Checklist. Patients answered each question with “yes” or “no” followed by detailed explanations. For example, in category “d110 Watching”, patients were asked “Have you ever felt difficult seeing things or people after the symptoms of BD appeared?” If the patients answered “yes”, the interviewer solicited details about problems; for example, when did it happen, how long did it last, how did you feel, how did you deal with it, etc. If the story told in detail by the patients contained content other than 128 categories from the ICF Checklist, the research team consisting of physicians, a nurse, and a medical social worker considered whether there was corresponding any ICF categories other than the ICF Checklist. As a result, another 12 ICF categories were added a checklist of 92 categories was created (BD-checklist 92) (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the process for creating the BD-checklist 92.

Study to identify physical and psychosocial problems in patients with BD

Patients

Using the BD-checklist created in the pilot study, we recruited new patients with BD to participate in a survey to identify physical and psychosocial problems in patients with BD. For recruitment, physicians explained the survey after outpatient treatment, and all patients who provided consent were surveyed. We excluded the 30 patients who had already participated in the pilot study. The 100 outpatients with BD who consented to participate were recruited from Teikyo University Hospital in Tokyo, Japan between January 2016 and April 2017. The diagnosis of BD was based on the International Criteria for BD [10]. Patients were excluded if they had severe dementia.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The Teikyo University Review Board approved this study (Approval Number 14-044).

Data collection and procedures

Patients were interviewed using the “BD-checklist 92” and asked whether they had experienced any of the problems in each category since they developed BD. Because most of the participants in the present study were in the remission phase, they were asked to recall the most prominent symptoms they had experienced in the acute phase. They were also asked to report their current health status at the time of the investigation. Patients answered each question either “yes” or “no.” For example, in category “b134 Sleep functions,” patients were asked “Have you ever been unable to sleep because of joint, oral and genital ulcer, eye and other pain after BD was diagnosed?” If the patient answered “yes,” the interviewer solicited details about the problem, such as when did it happen, how long did it last, how did you feel, how did you overcome the symptoms, etc. The interviews were conducted by the first author (HT), and it took 40–60 min to complete the 92 categories.

Instruments

The “BD-checklist 92” consists of 33 categories from the “Body functions” component, 8 categories from the “Body structures” component, 31 categories from the “Activities and participation” component, and 20 categories from the “Environmental factors” component.

Degree of severity of BD

Patients with BD were grouped according to the degree of severity of BD classified by the MHLW [11]: Stage I, the main symptoms of BD (oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, and skin involvement) except eye involvement; Stage II, i, symptom of Stage I + iridocyclitis; Stage II, ii, symptoms of Stage I + arthritis or epididymitis; Stage III, chorioretinitis; Stage IV, i, possibility of blindness or blindness due to chorioretinitis and other ocular complications, Stage IV, ii, activity or special disease type leading severe sequelae (intestinal BD, vascular BD, and neuro BD); and Stage V, i, BD of special type that risks life prognosis, Stage V, ii, chronic progressive neuro BD with moderate or more intelligence diminution. A higher stage number indicates more severe disease.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted based on all 130 patients, including the 30 in the pilot study and the 100 in the follow-up study.

Clinical parameters were compared between patients with and without each symptom (that is, arthritis, fatigue, skin manifestations, eye involvement, and genital ulceration). We compared the problem categories of patients with and without these symptoms based on a previous study [12]. Categorical variables were examined using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were analyzed by the t-test. Data on age, duration of BD, age of onset of BD, and number of problem categories were calculated as means and standard deviations. We also used the F-test to confirm the normality of the distribution of numerical variables.

A logistic regression model was used to investigate the odds ratios (OR) for experiencing problem categories in the “BD checklist-92” compared with not experiencing problems. The ORs for the problem categories experienced, along with the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), were calculated after adjusting for sex, age, duration of BD, age at onset, and stage of BD.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software package (IBM SPSS Statistics Desktop version 24.0, for Microsoft Windows, Armonk, NY). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Comparisons of baseline characteristics between patients with and without each symptom are shown in Table 2. The mean age of patients was 60 years, and the mean duration of BD was 24.6 years. The most frequent symptoms of BD were oral ulcers in 100%, skin involvement in 85.4%, genital ulcers in 81.5%, and eye involvement in 51.5%. Patients with Stage IV disease made up the largest group (57 patients), followed by those with Stage I disease (44 patients).

When looking at baseline characteristics of patients with and without each symptom, the mean age of patients with eye involvement was significantly older than those without eye involvement (63 vs. 57 years, P = 0.024), and the duration of BD in patients with genital ulcers, eye involvement, and skin involvement was significantly longer compared with patients without these symptoms (26.1 vs. 17.8 years, 28.4 vs. 20.5 years, and 25.6 vs. 18.6 years, P = 0.008, 0.001, and 0.047, respectively). In terms of symptoms of BD, skin involvement in the group of patients with genital ulcers (90.6 vs. 62.5%, P < 0.001) and genital ulcers in the group of patients with skin involvement (86.5 vs. 52.6%, P < 0.001) were reported significantly more frequently than in those without these symptoms. On the other hand, arthritis in the group of patients with eye involvement (50.7 vs. 68.3%, P = 0.042) and eye involvement in the group of patients with arthritis (44.2 vs. 62.3%, P = 0.042) were reported significantly less frequently than in those without those symptoms. In terms of the degree of severity of BD, Stage IV was the largest group except for the group with fatigue.

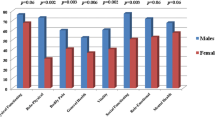

Mean number of problem categories for “BD checklist-92” by symptom (Table 2)

The mean number of problem categories in the component of “Body functions” was significantly greater in the group with arthritis (P < 0.001) and fatigue (P = 0.016) compared with the group without these symptoms. In the component of “Body structures”, the group with genital ulcers (P < 0.001), skin involvement (P = 0.007), and fatigue (P = 0.047) had a significantly greater number of problem categories than the group without these symptoms. The mean number of problem categories for the components of “Activities and participation” and all individual components were significantly higher in patients with eye involvement (both P < 0.001) and fatigue (both P < 0.005) than those without these symptoms. The number of problem categories in “Environmental factors” was significantly greater in the group with eye involvement (P = 0.006) compared with the group without eye involvement.

ORs for problem categories in each “BD-checklist 92” (Table 3)

Tables 3 shows the ORs of reported problem categories in each of the 4 components for each symptom of BD compared with the absence of a symptom.

Multivariate logistic regression models revealed that compared with patients without various symptoms, patients with various symptoms were more likely to have difficulty with physical problems and problems with social activities and participation after adjusting for sex, age, age at onset, duration of BD, and stage of BD. Patients with skin involvement and arthritis were more likely to experience physical problems. In contrast, BD patients with eye involvement and fatigue were more likely to experience problems in daily life.

Discussion

In the present study, the number of problem categories was significantly greater in patients with BD with eye involvement and fatigue. Specifically, patients with eye involvement and fatigue had more difficulties with problems in daily life, such as writing, understanding nonverbal messages such as gestures and facial expressions, walking, moving, walking in intense sunlight and bright light, and climate problems such as symptoms getting worse at the turn of the seasons or on cold days, compared to without these symptoms.

In patients with BD with genital ulcers, skin involvement, and arthritis, significant differences were seen in the number of problem categories associated with physical problems; however, no significant differences were found in the number of problem categories associated with psychosocial problems.

When symptoms of genital ulcers appeared, many patients experienced problems in daily life and work. Genital ulcers are painful and interfere with sitting and walking [13]. Therefore, patients may have been forced to limit their daily activities because of this pain. Blackford et al. [14] found that oral and genital ulcers may cause deterioration in personal relationships and daily activity and impact the QOL of patients with BD. Senusi et al. [15] indicated that genital ulcer pain was the major reason for difficulties in sexual activity, walking, and sitting.

Moreover, patients with genital ulcers were more likely to have hypertension compared with patients without genital ulcers, although the reason for this finding is not clear. The P-value was marginal and may be coincidental. Further study is necessary explain these findings.

This study showed that patients with eye involvement were significantly more likely to experience problems with both daily life activities and social participation. These problems included watching people and things, reading newspapers and books, writing letters and drawing pictures, understanding nonverbal messages such as gestures and facial expressions, going up and downstairs, driving cars and riding bicycles, and walking under intense sunlight and bright light.

Eye involvement such as uveitis is often seen in patients with BD [16]. In some cases, eye involvement leads to loss of vision. Therefore, patients with eye involvement are markedly limited in their daily life activities, and their QOL is decreased [12, 17, 18]. Based on the SF-36, Fabiani et al. reported that the physical functioning score was significantly worse in patients with BD with eye disease than in patients with BD without ocular involvement [16].

Although previous studies have reported on the low QOL in patients with BD with eye involvement [4, 12], there have yet to be investigations on specific daily living problems, such as difficulties encountered when communicating due to an inability to read nonverbal messages. Moreover, although many patients with uveitis have reported varying degrees of visual field reduction, reductions in contrast sensitivity, changes in depth and color perception, and increases in photosensitivity [19], there have been no specific reports on the difficulties faced by patients with BD due to issues caused by light.

The present study found that patients with skin involvement were significantly more likely to experience physical problems including pain, scarring, and tingling. These identified areas were consistent with previous reports [19, 20]. In addition, many patients with skin involvement had problems with sexual activity. This may be related to findings in one study that showed that 90% of patients with BD who experienced skin involvement experienced genital ulcers [15, 21].

Moreover, our patients reported worse symptoms based on climate and seasonal changes compared with patients who did not have skin involvement. Within the scope of our investigation, we have not seen any reports of worsening of symptoms due to the climate or seasonal changes limited to skin involvement in BD. However, Lee et al. report a higher rates of relapse of symptoms in spring and autumn, although that report was limited to intestinal BD [22], Krause et al. reported that seasonal exacerbation of joint pain, mainly related to autumn (50%) and/or spring (38%) [23], and Kim et al. reported that some patients with BD had worse symptoms in spring and autumn [24]. Lee et al. surmised that the high rate of symptom relapse due to seasonal changes may be related to the effects of a large temperature difference between day and night in spring and autumn on the immune system and vitamin D deficiency [22]. These conditions may also apply to our patients.

Compared with patients without arthritis, patients with arthritis were more likely to experience physical problems such as dizziness, respiratory discomfort, nausea, and pain on joint movement.

Arthritis in patients with BD is a common finding, with a prevalence rate from 40 to 70% [25]. Musculoskeletal diseases such as arthritis are painful. It has been postulated that pain disturbs the system that normally maintains balance during movement [26]. Morinaka reported that among patients with pain from musculoskeletal disease, 56% had dizziness and 43% had vertigo [27]. Moreover, arthritis can interfere with physical functioning and activity levels [28, 29]. Therefore, patients with BD with arthritis are prone to have reductions in muscle mass due to decreased physical activity. Sillanpää et al. [30] showed that in older individuals, loss of muscle strength initiates a causal chain that contributes to decreased pulmonary function and mobility limitations. The mean age of onset of arthritis in patients in the present study was 61 years, which is categorized as a relatively older generation; thus the symptoms of arthritis may be intensified to some extent.

The present study found that patients with fatigue were significantly more likely to experience daily life problems including movements using fingertips, such as needlework, eating, domestic duties, and neighborhood relationships. Furthermore, many patients with fatigue reported an impact of climate change.

Fatigue is an important problem in inflammatory diseases and affects QOL [12, 31]. Fatigue is likely to cause various limitations in daily life such as housework and/or daily activities. Some studies have pointed out a relationship between self-perceived fatigue, functional disability, and performance restriction in daily activities [32, 33]. In addition, Soares et al. reported that fatigue was associated independently with functional performance and activity restriction needed to perform instrumental and advanced daily activities in a study of older people [33]. Therefore, our patients with fatigue might be more likely to experience daily life problems such as those listed above. Furthermore, fatigue is classified into physical and mental fatigue. Ilhan et al. reported that mental symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, and physical dysfunction were significantly associated with fatigue in patients with BD [31]. Mental fatigue may have made our patients feel that it is troublesome for them to interact with their neighbors.

In addition, compared with patients without fatigue, patients with fatigue were more likely to experience seasonal differences in symptoms. Although there are not many reports on the relationship between weather conditions or seasonal variation and worsened symptoms of BD, Bang et al. [34] reported that the symptoms seem to be aggravated more frequently in the spring, summer, and winter and less frequently in the fall. In terms of the components of body function and structures in our patients, the number of problem categories was significantly higher in the fatigue group than in the non-fatigue group (P = 0.016 and 0.047, respectively), and the impact of mental symptoms on daily life was greater in the fatigue group than in the non-fatigue group (P = 0.001). Because the severity of fatigue has been shown to correlate with impaired functioning and psychological symptoms [35], our patients with BD with fatigue may have experienced more physical and mental problems.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the survey was performed based on the recall of participants. Thus, the results may be prone to recall bias. On the other hand, recalling their acute phase symptoms may eliminate overstatement related to the anxiety or discomfort that the patients may have felt when describing symptoms in the acute phase. Second, the sample size was limited, as the study patients were recruited at a single hospital in Tokyo; this might limit the generalizability of the results. In this regard, we plan to conduct a mail survey using the “BD-Checklist 92” for BD patients nationwide.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the number of problem categories was significantly greater in Japanese patients with BD with eye involvement and fatigue. Patients with BD with eye involvement and fatigue often experienced many problems with daily activities and instrumental activities of daily living. For patients with BD with these symptoms, it is suggested that support focus not only on physical symptoms but also on activities that are part of daily life.

References

Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G (1999) Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med 341:1284–1291

Bernabé E, Marcenes W, Mather J, Phillips C, Fortune F (2010) Impact of Behçet’s syndrome on health-related quality of life: influence of the type and number of symptoms. Rheumatology 49:2165–2171

Moses Alder N, Fisher M, Yazici Y (2008) Behçet’s syndrome patients have high levels of functional disability, fatigue and pain as measured by a Multi-dimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 26:S110–S113

Ertam I, Kitapcioglu G, Aksu K, Keser G, Ozaksar A, Elbi H, Unal I, Alper S (2009) Quality of life and its relation with disease severity in Behçet’s disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27:S18–22

Talarico R, Palagini L, Elefante E et al (2018) Behçet's syndrome and psychiatric involvement: is it a primary or secondary feature of the disease? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 36:125–128

Talarico R, Palagini L, d'Ascanio A et al (2015) Epidemiology and management of neuropsychiatric disorders in Behçet's syndrome. CNS Drugs 29:189–196

World Health Organization (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. WHO, Geneva

Stuki G, Ewert T, Cieza A (2002) Value and application of the ICF in rehabilitation medicine. Disabil Rehabil. 24:932–938

International Study Group for Behçet's Disease (1990) Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Lancet 335:1078–1080

World Health Organization (2001) ICF Checklist Version 2.1α, Clinical Form for International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, WHO.

Hirohata S (2007) Diagnosis and therapy for Behcet disease. J Jpn Soc Int Med 96:2220–2225 (in Japanese)

Melikoğlu M, Melikoglu MA (2014) What affects the quality of life in patients with Behcet’s disease? Acta Reumatol Port 39:46–53

Alpsoy E, Zouboulis CC, Ehrlich GE (2007) Mucocutaneous lesions of Behcet’s disease. Yonsei Med J 48:573–585

Blackford S, Finlay AY, Roberts DL (1997) Quality of life in Behçet’s syndrome: 335 patients surveyed. Br J Dermatol 136:293

Senusi A, Seoudi N, Bergmeier LA, Fortune F (2015) Genital ulcer severity score and genital health quality of life in Behçet’s disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 10:117

Atay IM, Erturan I, Demirdas A, Yaman GB, Yürekli VA (2014) The impact of personality on quality of life and disease activity in patients with Behcet’s disease: a pilot study. Compr Psychiatry 55:511–517

Fabiani C, Vitale A, Orlando I, Sota J, Capozzoli M, Franceschini R, Galeazzi M, Tosi GM, Frediani B, Cantarini L (2017) Quality of life impairment in Behçet’s disease and relationship with disease activity: a prospective study. Intern Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-017-1691-z

Koca I, Savas E, Ozturk ZA, Tutoglu A, Boyaci A, Alkan S, Kisacik B, Onat AM (2015) The relationship between disease activity and depression and sleep quality in Behçet’s disease patients. Clin Rheumatol 34:1259–1263

Mat MC, Sevim A, Fresko I, Tüzün Y (2014) Behçet's disease as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol 32:435–442

Ulaş Y (2017) Skin and Mucosa Findings of Behçet’s Disease. Behcet’s disease—a compilation of recent research and review studies. https://smjournals.com/ebooks/behcets-disease/chapters/BD-17-12.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2019.

Gül IG, Kartalc Ş, Cumurcu BE, Karıncaoğlu Y, Yoloğlu S, Karlıdağ R (2013) Evaluation of sexual function in patients presenting with Behçet's disease with or without depression. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 27:1244–1251

Lee JH, Cheon JH, Hong SP, Kim T, Kim WH (2015) Seasonal variation in flares of intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 60:3373–3378

Krause I, Shraga I, Molad Y, Guedj D, Weinberger A (1997) Seasons of the year and activity of SLE and Behcet's disease. Scand J Rheumatol 26:435–439

Kim HJ, Bang D, Lee SH, Yang DS, Kim DH, Lee KH, Lee S, Kim HB, Hong WP (1988) Behçet's syndrome in Korea: a look at the clinical picture. Yonsei Med J 29:72–78

Yurdakul S, Yazici H, Tüzün Y, Pazarli H, Yalçin B, Altaç M, Ozyazgan Y, Tüzüner N, Müftüoğlu A (1983) The arthritis of Behçet's disease: a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 42:505–515

Mouchnino L, Gueguen N, Blanchard C, Boulay C, Gimet G, Viton JM, Franceschi JP, Delarque A (2005) Sensori-motor adaptation to knee osteoarthritis during stepping-down before and after total knee replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 6:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-6-21

Morinaka S (2009) Musculoskeletal diseases as a causal factor of cervical vertigo. Auris Nasus Larynx 36:649–654

Perruccio AV, Power JD, Badley EM (2007) The relative impact of 13 chronic conditions across three different outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health 61:1056–1061

Slater M, Perruccio AV, Badley EM (2011) Musculoskeletal comorbidities in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease: the impact on activity limitations; a representative population-based study. BMC Public Health 11:77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-77

Sillanpää E, Stenroth L, Bijlsma AY, Rantanen T, McPhee JS, Maden-Wilkinson TM, Jones DA, Narici MV, Gapeyeva H, Pääsuke M, Barnouin Y, Hogrel JY, Butler-Browne GS, Meskers CG, Maier AB, Törmäkangas T, Sipilä S (2014) Associations between muscle strength, spirometric pulmonary function and mobility in healthy older adults. Age (Dordr) 36:9667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-014-9667-7

Ilhan B, Can M, Alibaz-Oner F, Yilmaz-Oner S, Polat-Korkmaz O, Ozen G, Mumcu G, Maradit Kremers H, Direskeneli H (2016) Fatigue in patients with Behcet’s syndrome: relationship with quality of life, depression, anxiety, disability and disease activity. Int J Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12839

Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, Eldadah B, Cesari M, Ferrucci L, Ceresini G, Guralnik JM (2009) Fatigue in a representative population of older persons and its association with functional impairment, functional limitation, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64:76–82

Soares WJ, Lima CA, Bilton TL, Ferrioli E, Dias RC, Perracini MR (2015) Association among measures of mobility-related disability and self-perceived fatigue among older people: a population-based study. Braz J Phys Ther 19:194–200

Bang D, Yoon KH, Chung HG, Choi EH, Lee ES, Lee S (1997) Epidemiological and clinical features of Behçet's disease in Korea. Yonsei Med J 38:428–436

Kitai E, Blumberg G, Golan-Cohen A, Levi D, Vinker S (2015) Seasonality of fatigue among young adults in the primary care setting. Public Health 129:591–593

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K04187. The authors thank M. Ishida, Researcher, National Institute of Mental Health, Department of Adult Mental Health, for excellent advice from the perspective of nursing care in BD.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K04187.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsutsui, H., Kikuchi, H., Oguchi, H. et al. Identification of physical and psychosocial problems based on symptoms in patients with Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int 40, 81–89 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04488-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04488-1