Abstract

We investigate evolutionary dynamics of two-strategy matrix games with zealots in finite populations. Zealots are assumed to take either strategy regardless of the fitness. When the strategy selected by the zealots is the same, the fixation of the strategy selected by the zealots is a trivial outcome. We study fixation time in this scenario. We show that the fixation time is divided into three main regimes, in one of which the fixation time is short, and in the other two the fixation time is exponentially long in terms of the population size. Different from the case without zealots, there is a threshold selection intensity below which the fixation is fast for an arbitrary payoff matrix. We illustrate our results with examples of various social dilemma games.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A standard assumption underlying evolutionary game dynamics, regardless of whether a player is social agent or gene, is that players tend to imitate successful others. In actual social evolutionary dynamics, however, there may be zealous players that stick to one option according to their idiosyncratic preferences regardless of the payoff that they or their peers earn. Collective social dynamics in the presence of zealots started to be examined for non-game situations such as the voter model representing competition between two equally strong opinions (i.e., neutral invasions) (Mobilia 2003; Galam and Jacobs 2007; Mobilia et al. 2007; Xie et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2012). Zealots seem to be also relevant in evolutionary game dynamics. For example, voluntary immunization behavior of individuals when epidemic spreading possibly occurs in a population can be examined by a public-goods dilemma game (Fu et al. 2011). In this situation, some individuals may behave as zealot such that they try to immunize themselves regardless of the cost of immunization (Liu et al. 2012).

In our previous work, we examined evolutionary dynamics of the prisoner’s dilemma and snowdrift games in infinite populations with zealots (Masuda 2012). Specifically, we assumed zealous cooperators and asked the degree to which the zealous cooperators facilitate cooperation in the entire population. We showed that cooperation prevails if the temptation of unilateral defection is weak or the selection strength is weak. For the prisoner’s dilemma, we analytically obtained the condition of cooperation.

In the present paper, we conduct a finite population analysis of evolutionary dynamics of a general two-person game with zealots. Evolutionary games in finite populations have been recognized as a powerful analytical tool for understanding properties of evolutionary games such as conditions of cooperation in social dilemma games. In addition, the outcome for finite populations is often different from that for infinite populations (Nowak et al. 2004; Taylor et al. 2004; Nowak 2006). We take advantage of this method to understand evolutionary dynamics of games with zealots for general matrix games.

It should be noted that the fixation probability, i.e., the probability that a given strategy eventually dominates the population as a result of stochastic evolutionary dynamics, is a primary quantity to be pursued in evolutionary dynamics in finite populations. Nevertheless, fixation trivially occurs in the presence of zealots if all zealots are assumed to take the same strategy; the zealots’ strategy always fixates. For example, if there is a single zealous cooperator in the population, cooperation always fixates even in the conventional prisoner’s dilemma game. However, in this adverse case, fixation of cooperation is expected to take long time; the relevant question here is the fixation time (Antal and Scheuring 2006; Traulsen et al. 2007; Altrock and Traulsen 2009; Altrock et al. 2010; Assaf and Mobilia 2010; Ewens 2010; Wu et al. 2010; Altrock et al. 2011; Assaf and Mobilia 2012; Kreindler and Young 2013). Here we examine the mean fixation time of the strategy selected by the zealots. This quantity serves as a probe to understand the extent to which zealots influence non-zealous players in the population. The fixation time would be affected by the payoff matrix, population size, number of zealous players, and strength of selection. We derive the asymptotic dependence of the mean fixation time on the population size when the fraction of zealots in the population is fixed. Mathematically, we extend the approach taken in Antal and Scheuring (2006) to the case with zealots.

2 Model

We assume a well-mixed population of \(N+M\) players under evolutionary dynamics defined as follows. In each discrete time unit, each player selects either of the two strategies \(A\) or \(B\). Each player plays a symmetric two-person game with all the other \(N+M-1\) players in a unit time. The payoff matrix of the single game for the row player is given by

The fitness of a player on which the selection pressure operates is defined as the payoff summed over the \(N+M-1\) opponents.

We assume that \(N\) players may flip the strategy according to the Moran process (Moran 1958; Ewens 2010). We call these players the ordinary players. The other \(M\) players are zealots that never change the strategy irrespectively of their fitness. Because our primary interest is in the possibility of cooperation in social dilemma games induced by zealous cooperators, we assume that all zealots take strategy \(A\); \(A\) is identified with cooperation in the case of a social dilemma game. We also assume that \(a, b, c, d \ge 0\) for the Moran process to be well-defined.

Because we have assumed a well-mixed population, the state of the evolutionary process is specified by the number of ordinary players selecting \(A\), which we denote by \(i\). In each time step, we select an ordinary player with the equal probability \(1/N\). The strategy of the selected player is updated. Then, we select a player, called the parent, whose strategy replaces that of the previously selected player. The parent is selected with the probability proportional to the fitness among the \(N+M\) players including the zealots and the player whose strategy is to be replaced. The population size \(N\) is constant over time. It should be noted that a player is updated once on average in time \(N\).

Because the zealots always select \(A\), the Moran process ends up with the unanimous population of \(A\) players (we impose \(a>0\) for this to be true). In other words, fixation of \(A\) always occurs such that the issue of fixation probability is irrelevant to our model.

3 Results

We calculate the mean fixation time and its approximation in the case of a large population size by extending the framework developed in Antal and Scheuring (2006) (also see Van Kampen 2007; Redner 2001; Krapivsky et al. 2010; Ewens 2010).

3.1 Mean fixation time: exact solution

Consider the state of the population in which \(i\) (\(0\le i\le N\)) ordinary players select strategy \(A\). A total of \(i+M\) and \(N-i\) players, including the zealots, select strategies \(A\) and \(B\), respectively. The Moran process is equivalent to a random walk on the \(i\) space in which \(i=0\) is a reflecting boundary, and \(i=N\) is the unique absorbing boundary.

The fitness of an \(A\) and \(B\) player is given by

and

respectively. In a single time step, \(i\) increases by one, does not change, or decreases by one. We denote by \(T^+_i\) and \(T^-_i\) the probabilities that \(i\) shifts to \(i+1\) and \(i-1\), respectively. These probabilities are given by

and

We denote by \(t_i\) the mean fixation time when there are initially \(i\) ordinary players with strategy \(A\). As shown in Ewens (2010), pp. 86–91 (see Appendix A for a full derivation), we obtain

where

In Eq. (7), we interpret \(q_0 = 1\).

3.2 Deterministic approximation of the random walk

In this section we classify the deterministic dynamics driven by the expected bias of the random walk (i.e., \(T_i^+ - T_i^-\)) into three cases, as is done in the analysis of populations without zealots (Taylor et al. 2004; Antal and Scheuring 2006). The obtained classification determines the dependence of the mean fixation time on \(N\), as we will show in Sect. 3.3.

We first identify the equilibrium points of the deterministic dynamics, i.e., \(i\) satisfying \(T^+_i = T^-_i\). Equations (4) and (5) indicate that \(i=N\) always yields \(T^+_i = T^-_i=0\), corresponding to the fact that \(i=N\) is the unique absorbing state. Other equilibria are derived from

We set \(y\equiv i/N\) (\(0\le y< 1\)), \(m\equiv M/N\), and ignore \(O(N^{-1})\) terms in Eq. (8) to obtain

We define

and

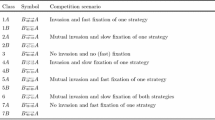

We will use \(y^*_2\) only when \(a-b-c+d>0\). In the continuous state limit, the deterministic dynamics driven by \(T_i^+-T_i^-\) is classified into the following three cases, as summarized in Table 1. The derivation is shown in Appendix B.

-

Case (i)

: \(f(y)> 0\) holds true for all \(y\) (\(0\le y\le 1\)) such that the dynamics starting from any initial condition tends to \(y=1\) (Fig. 1a). In an infinite population, \(A\) dominates \(B\). In a finite population, we expect that the fixation time is short. This case occurs when \(c < (m+1)a\) and one of the following conditions is satisfied:

-

\(a-b-c+d \le 0\).

-

\(a-b-c+d > 0\) and \(y_1^*\le 0\) (i.e., \(2ma+(-m+1)b-mc-d\ge 0\)).

-

\(a-b-c+d > 0\), \(0<y_1^*<1\) (i.e., \(2ma+(-m+1)b-mc-d<0\) and \(-(2m+2)a+(m+1)b+(m+2)c-d<0\)), and \(D \le 0\).

-

\(a-b-c+d > 0\) and \(y_1^*\ge 1\) (i.e., \(-(2m+2)a+(m+1)b+(m+2)c-d\ge 0\)).

-

-

Case(ii)

: \(f(y)=0\) has a unique solution \(y^*_1\) (\(0< y^*_1<1\)) such that the dynamics starting from any initial condition converges to \(y^*_1\) (Fig. 1b). In an infinite population, \(A\) and \(B\) coexist. In a finite population, we expect that the fixation time is long. This case occurs when \(c > (m+1)a\).

-

Case (iii)

: \(f(y)=0\) has two solutions \(0<y^*_1 < y^*_2<1\). Dynamics starting from \(0\le y<y^*_2\) converges to \(y^*_1\), and that starting from \(y^*_2<y<1\) converges to \(y=1\) (Fig. 1c). In an infinite population, a mixture of \(A\) and \(B\) and the pure \(A\) configuration are bistable. In a finite population, we expect that the fixation time is long if the dynamics starts with \(0\le y<y^*_2\) and short if it starts with \(y^*_2<y<1\). This case occurs when

$$\begin{aligned}&c < (m+1)a, \end{aligned}$$(14)$$\begin{aligned}&a-b-c+d > 0,\end{aligned}$$(15)$$\begin{aligned}&0<\tilde{y}<1, \end{aligned}$$(16)and

$$\begin{aligned} D > 0 \end{aligned}$$(17)are satisfied.

Schematic classification of the deterministic dynamics driven by \(T_i^+-T_i^-\). a–c Populations with zealots. d–g Populations without zealots. Filled and open circles represent stable and unstable equilibria, respectively. Filled squares represent the absorbing boundary condition. It should be noted that we identify \(y=i/N\)

The condition given by Eq. (14) is related to the so-called cooperation facilitator assumed in a previous model (Mobilia 2012) as follows. Consider a hypothetical infinite population in which almost all players select \(A\), i.e., \(y\approx 1\). Then, the payoff that a player with strategy \(A\) gains by being matched with the other ordinary players and zealous players is equal to \((m+1)a\). The payoff that a player with strategy \(B\) gains by being matched with the other ordinary players, but not zealous players, is equal to \(c\). Therefore, Eq. (14) represents the condition for the stability of the homogeneous population of strategy \(A\) against invasion by \(B\) when zealous players somehow contribute to the payoff of ordinary \(A\) players and not to that of ordinary \(B\) players. Such a zealous player is equivalent to the cooperation facilitator assumed in Mobilia (2012).

In the corresponding model without zealots, there are four scenarios: \(A\) dominates \(B\) (Fig. 1d), \(B\) dominates \(A\) (Fig. 1e), a mixture of \(A\) and \(B\) is stable (Fig. 1f), and \(A\) and \(B\) are bistable (Fig. 1g) (Antal and Scheuring 2006). The cases shown in Fig. 1d, f, and g are analogous to cases (i), (ii), and (iii), respectively, for the game with zealots. The case shown in Fig. 1e never occurs in the game with zealots because \(y\) tends to increase in the absence of \(A\) owing to the fact that unanimity of \(B\) among the ordinary players is a reflecting boundary of our model. In fact, this case corresponds to case (ii) for the presence of zealots (Fig. 1b). If we set \(m\rightarrow 0\), we obtain case (i) when \(a-c>0\) and \(b-d>0\), case (ii) when \(a-c<0\), and case (iii) when \(a-c>0\) and \(b-d<0\). As is consistent with Antal and Scheuring (2006), the classification depends only on the \(a-c\) and \(b-d\) values. However, the scenario in which \(B\) dominates \(A\) (Fig. 1e) does not happen even with the vanishing density of zealots (i.e., \(m\rightarrow 0\)) because the unanimity of \(B\) remains to be a reflecting boundary as long as there is at least one zealot.

3.3 Mean fixation time: large \(N\) limit

In this section, we analyze the order of the mean fixation time in terms of \(N\) when \(N\) is large. We assume that the fraction of zealots in the population, i.e., \(m=M/N\), is fixed. Because the mean fixation time is by definition the largest for \(i=0\), i.e., the initial condition in which all ordinary players select \(B\), we focus on \(t_0\). To evaluate \(t_0\), we rewrite Eq. (6) for \(i=0\) as

3.3.1 Case (i)

We obtain

where \(f(y)\) (\(0\le y<1\)) is given by Eq. (9). In case (i), \(f(y)>0\) holds true. Therefore,

is satisfied for \(0\le i\le N-1\). By using Eq. (20), we obtain

Because the left-hand side of Eq. (21) is at least unity, we obtain

The substitution of \(y = i/N\) and \(m = M/N\) in Eq. (4) yields

In particular, we obtain

Equation (24) implies that

This result coincides with the previous result for the absence of zealots (Antal and Scheuring 2006).

3.3.2 Case (ii)

In Case (ii), \(T^+_i-T^-_i>0\) for \(0\le i<N y^*_1\) and \(T^+_i-T^-_i <0\) for \(N y^*_1 <i<N\). Therefore, \(q_i\) takes the minimum at \(i\approx N y^*_1\). We denote the value of \(i\) that satisfies \(i<N y^*_1\) and \(q_i\approx q_{N-1}\) by \(i^*\). Such an \(i^*\) exists if \(q_0\ge q_{N-1}\). If \(q_0<q_{N-1}\), we regard that \(i^*=0\). Using the relationship \(q_i = \left[ \tilde{q}(i/N)\right] ^N\) for a function \(\tilde{q}(y)\) (\(0\le y<1\)) (Antal and Scheuring 2006) (also see Appendix C), we obtain

where

To derive the last line in Eq. (26), we used the steepest descent method (Antal and Scheuring 2006) (also see Appendix D).

Equations (23) and (24) imply that \(1/T_k^+\) in Eq. (26) is safely ignored near the singularity at \(y\approx 1\) because it would contribute at most \(\propto N\ln N\) to the fixation time. Therefore, we obtain

where \(\gamma > 0\) is a constant that depends on \(a, b, c, d\), and \(m\). The dependence of \(\gamma \) on \(m\) is shown in Fig. 2 for sample payoff matrices for the prisoner’s dilemma game (solid line) and snowdrift game (dotted line). For both games, \(\gamma \) monotonically decreases with \(m\), implying that the fixation time decreases with \(m\). In particular, \(\gamma \) is equal to zero, which corresponds to \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), when \(m\) is larger than a threshold value.

The exponent \(\gamma \) for the mean fixation time [Eq. (28)] plotted against the density of zealots \(m\) for the prisoner’s dilemma game with \(a=1\), \(b=0\), \(c=1.2\), and \(d=0\) (solid line) and the snowdrift game with \(a=\beta -0.5\), \(b=\beta \), \(c=\beta -1\), \(d=0\), with \(\beta =1.5\) (dotted line). We calculated \(\gamma \) on the basis of Eqs. (26), (27), and (55)

3.3.3 Case (iii)

In this case, \(q_i\) takes a local minimum at \(i=Ny^*_1\) and a local maximum at \(i=Ny^*_2\). Therefore, behavior of the random walk in the range \(0\le i <Ny^*_2\) is qualitatively the same as that for case (ii), and that in the range \(Ny^*_2<i<N\) is qualitatively the same as that for case (i). Because the former part makes the dominant contribution to the fixation time, the scaling of the mean fixation time is given by Eq. (28).

Case (iii) occurs when strategy \(A\) is disadvantageous when it is rare and advantageous when it is frequent. The coordination game provides such an example (Sect. 5.4).

3.3.4 Summary and the borderline case

In summary, the mean fixation time in the limit of large \(N\) is given by \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\) in case (i) and \(t_0 \propto \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) (\(\gamma >0\)) in cases (ii) and (iii). For the parameter values on the boundary between the two scaling regimes, the same arguments as those for the model without zealots (Antal and Scheuring 2006) lead to \(t_0 \propto N^{3/2}\).

4 Dependence of the mean fixation time on the selection strength

We examine the influence of the selection strength, denoted by \(w\), on the mean fixation time. To this end, we redefine the fitness to an \(A\) and \(B\) player by \(1-w+wf_i\) and \(1-w+wg_i\), respectively, where \(f_i\) and \(g_i\) are given by Eqs. (2) and (3) (e.g., Nowak et al. 2004; Nowak 2006). Consequently, we replace the payoff matrix given by Eq. (1) by

Equation (1) is reproduced with \(w=1\).

For sufficiently weak selection, we obtain \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), i.e., case (i), regardless of the payoff matrix. To prove this statement, we note that, by using the payoff matrix shown in Eq. (29), condition \(c < (m+1)a\) in the case of \(w=1\) is generalized to

Therefore, if the original game in the case of \(w=1\) belongs case (ii), i.e., \(c > (m+1)a\), the game belongs to case (i) or (iii) (Table 1) if Eq. (30), or equivalently,

is satisfied. For a fixed payoff matrix, \(w_1\) monotonically increases with \(m\), consistent with the intuition that existence of zealots would lessen the fixation time.

Next, the sign of \(a-b-c+d\) is not affected by the selection strength. Therefore, we assume \(a-b-c+d>0\) and prove that a condition for case (iii), i.e., Eq. (17), is violated with a sufficiently small \(w\). Because the value of \(\tilde{y}\) given by Eq. (10) is also unaffected by \(w\), we start with assuming \(0<\tilde{y}<1\), which is a necessary condition for case (iii) [Eq. (16); see Appendix B]. The condition \(D< 0\) in the case of \(w=1\), where \(D\) is defined by Eq. (11), is generalized to

Because the condition imposed on \(D\), which distinguishes cases (i) and (iii), is relevant only for \(a-b-c+d>0\) (Table 1), Eq. (32) is satisfied for an arbitrary payoff matrix if

Therefore, case (iii) is excluded with a sufficiently small \(w\) value.

The threshold value of \(w\) below which \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), which we denote by \(w_\mathrm{c}\), is given by

We can alternatively introduce the selection strength by replacing Eqs. (2) and (3) to redefine the fitness by

and

where \(\beta \) is the selection strength (Traulsen et al. 2008). In Appendix E, we show that qualitatively the same result holds true in the sense that there is a threshold value of \(\beta \) below which the fixation is fast irrespective of the \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), \(d\), and \(m\) values. It should be noted that, with Eqs. (35) and (36), \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(d\) are allowed to take negative values.

5 Examples

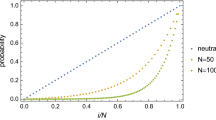

We compare the mean fixation time for some games with that for the neutral game, i.e., \(a = b = c = d >0\). In the absence of zealots, the neural game yields \(T_i^+=T_i^-\) (\(1\le i\le N-1\)). The random walk is unbiased, and the so-called mean conditional fixation time is equal to \(N(N-1)\) (Antal and Scheuring 2006). The mean conditional fixation time is defined as the mean fixation time starting from state \(i=1\) under the condition that the absorbing state at \(i=N\), not \(i=0\), is reached.

The neutral game in the presence of zealots yields \(T_0^+ > T_0^- = 0\) and \(T_i^+/T_i^-=(i+M)/i\) (\(1\le i\le N-1\)). Therefore, the random walk is biased toward \(i=N\) for all \(i\). More precisely, we obtain

As in Antal and Scheuring (2006), we say that fixation is fast (slow) if \(t_0\) is smaller (larger) than the value given by Eq. (37). It should be noted that \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\) for the neutral game because it corresponds to \(w=0<w_\mathrm{c}\).

5.1 Constant selection

As a first example, consider the case of frequency-independent selection such that \(A\) and \(B\) are equipped with fitness \(r\) and 1 (under \(w=1\)), respectively. When \(a=b=r\) and \(c=d=1\), the threshold selection strength below which \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), i.e., case (i), holds true is given by

If \(w>w_\mathrm{c}\), case (ii) occurs. Even if \(A\) is disadvantageous to \(B\), \(A\) fixates fast with the help of zealots regardless of the selection strength if \(1/(m+1)<r<1\). This condition is more easily satisfied when \(m\) is larger.

5.2 Prisoner’s dilemma game

Consider the prisoner’s dilemma game with a standard payoff matrix given by \(a=1\), \(b=0\), \(c=T\), and \(d=0\), where \(T>1\). Strategies \(A\) and \(B\) represent cooperation and defection, respectively. It should be noted that \(a-b-c+d < 0\). With a general selection strength, the conditions derived in Sect. 3.2 imply that \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), i.e., case (i), if \(T < 1+m/w\), and \(t_0 \propto \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) with case (ii) if \(T > 1+m/w\). This condition coincides with that for the dominance of cooperators in the case of the infinite population (Masuda 2012).

The mean fixation time with \(w=1\) and \(m=0.2\) obtained by direct calculations of Eq. (18) is shown in Fig. 3a. In this and the following figures, the \(t_0\) values are those normalized by that for the neutral game [Eq. (37)]. The behavior of \(t_0\) is qualitatively different according to whether \(T\) is larger or smaller than \(1+m/w=1.2\). If \(T<1.2\), the ratio of \(t_0\) for the prisoner’s dilemma game to \(t_0\) for the neutral game seems to approach a constant as \(N\rightarrow \infty \). This is consistent with case (i). In contrast, if \(T>1.2\), \(t_0\) grows rapidly, which is consistent with case (ii). To be more quantitative, \(400 \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) divided by the \(t_0\) value for the neutral game is shown by the dashed line in Fig. 3a. It should be noted that 400 is a constant for fitting and that \(\gamma \) value is theoretically determined as described in Sect. 3.3.2. The theory (dashed line) agrees well with the exact numerical results (thinnest solid line). We remark that the normalized \(t_0\) behaves non-monotonically in \(N\); it takes a minimum at an intermediate value of \(N\).

The normalized mean fixation time for the prisoner’s dilemma game as a function of \(N\). We set \(a=1\), \(b=0\), \(c=T\), and \(d=0\). In a, we set \(m=0.2\) and \(w=1\). In b, we set \(T=1.2\) and \(m=0.1\). In c, we set \(T=1.2\) and \(w=1\). The dashed lines represent \(400\sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) divided by the \(t_0\) value for the neutral game

Next, to examine the effect of the selection strength, we set \(T=1.2\) and \(m = 0.1\). The mean fixation time as a function of \(N\) and \(w\) is shown in Fig. 3b. Equation (34) implies that \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\) when \(w < w_\mathrm{c}= 0.5\). Consistent with this result, \(t_0\) grows fast as a function of \(N\) when \(w\) is large (i.e., \(w=0.7\) and 1). In particular, for \(w=1\), \(400 \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) normalized by the \(t_0\) value for the neutral game (dashed line in Fig. 3b) agrees well with the exact results (thin solid line). For small \(w\) (i.e., \(w=0.4\)), \(t_0\) seems to scale with \(N\ln N\) (thick solid line).

Figure 3c shows the dependence of \(t_0\) on \(N\) for different densities of zealots (i.e., \(m\)). It should be noted that the baseline \(t_0\) value derived from the neutral game depends on the value of \(m\). Because we set \(T=1.2\) and \(w=1\) in Fig. 3c, the threshold value of \(m\) is equal to 0.2. In fact, the normalized \(t_0\) diverges according to \(\propto \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) when \(m=0.1\) (dashed line and thick solid line), whereas it seems to converge to a constant value when \(m=0.3\) (thin solid line).

Figure 3 indicates that \(t_0\) for the prisoner’s dilemma game is always larger than that for the neutral game (i.e., the normalized \(t_0\) is larger than unity). This is consistent with the intuition that cooperation is difficult to attain in the prisoner’s dilemma game as compared to the neutral game.

Finally, consider the symmetrized donation game, which is another standard form of the prisoner’s dilemma game, given by \(a=b^{\prime }-c^{\prime }\), \(b=-c^{\prime }\), \(c=b^{\prime }\), and \(d=0\), where \(b^{\prime }\) is the benefit, and \(c^{\prime } (<b^{\prime })\) is the cost. For the Moran process to be well-defined, we require \(1-w+wb\ge 0\), i.e., \(w<1/(1+c^{\prime })\). For this payoff matrix, we obtain

Fixation occurs fast for a large benefit-to-cost ratio, large \(m\), or small selection strength.

5.3 Snowdrift game

In this section, we examine the snowdrift game (Maynard Smith 1982; Sugden 1986; Hauert and Doebeli 2004) defined by \(a=\beta -0.5\), \(b=\beta -1\), \(c=\beta \), and \(d=0\), where \(\beta >1\). Strategies \(A\) an \(B\) are identified as cooperation and defection, respectively. Each player is tempted to defect if the other player cooperates, as in the prisoner’s dilemma game. However, different from the prisoner’s dilemma game, a player is better off by cooperating if the partner defects; mutual defection is the worst outcome. In the infinite well-mixed population without zealots, the game has the unique mixed Nash equilibrium in which the fraction of cooperation is equal to \((2\beta -2)/(2\beta -1)\).

Numerical evidence for the replicator dynamics, corresponding to an infinite population, suggests that cooperation is dominant if \(m\) is large or \(w\) is small (Masuda 2012). For the finite population, we obtain

If \(w<w_\mathrm{c}\), we obtain \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), i.e., case (i). If \(w>w_\mathrm{c}\), we obtain \(t_0 \propto \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) with case (ii). A large value of \(\beta \) or \(m\) makes the fixation time smaller. This result makes sense because a large \(\beta \) generally favors cooperation.

5.4 Coordination game

The coordination game given by \(a=d>0\) and \(b=c=0\) has two pure Nash equilibria in the infinite well-mixed population without zealots. For a finite population in the presence of zealots, Eq. (34) yields

If \(w<w_\mathrm{c}\), we obtain \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\), i.e., case (i). It should be noted that any strength of selection \(0\le w\le 1\) yields \(t_0 \propto N\ln N\) if there are sufficiently many zealots, similar to the game with constant selection, prisoner’s dilemma game, and snowdrift game. If \(w>w_\mathrm{c}\), we obtain \(t_0 \propto \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) with case (iii).

The mean first-passage time from state 0 (i.e., all ordinary players select \(B\)) to state \(i\), i.e., \(\sum _{j=0}^{i-1} \sigma _j\), is shown in Fig. 4. It should be noted that \(t_0\) is equal to this first-passage time to exit \(i=N\). We set \(N=200\), \(a=d=1\), \(b=c=0\), \(m=0.2\), and \(w=1\). Equation (41) implies \(w_\mathrm{c}=48/49\) for these parameter values. Because \(w=1>w_\mathrm{c}\), we obtain case (iii).

The first-passage time increases slowly as \(i\) increases when \(i\) is small. It rapidly increases with \(i\) for intermediate values of \(i\), Once the random walker passes the critical \(i\) value, it feels a positive bias such that the first-passage time only gradually increases with \(i\) for large \(i\). The values of \(i\) that separate the three regimes are roughly consistent with the analytical estimates \(y^*_1 = 0.1\) and \(y^*_2 = 0.2\) [Eqs. (12), (13)]. It should be noted that the first-passage time shows representative behavior of case (iii) although \(w\) is only slightly larger than \(w_\mathrm{c}\).

6 Discussion

We extended the results for the fixation time under the Moran process (Antal and Scheuring 2006) to the case of a population with zealous players. Similar to the case without zealots (Antal and Scheuring 2006), we identified three regimes in terms of the payoff matrix, number of zealots, and selection strengths. In one regime, the fixation time is small (i.e., \(\propto N\ln N\)). In the other two regimes, it is large (i.e., \(\propto \sqrt{N}\exp (\gamma N)\) with \(\gamma >0\)). We illustrated our results with representative games including the prisoner’s dilemma game, snowdrift game, and coordination game.

Zealots have several impacts on evolutionary dynamics in finite populations. First, fixation of one strategy \(A\) always occurs with zealots because we assumed that all zealots permanently take \(A\). Second, there is a case in which fixation is fast if the fraction of \(A\) players is sufficiently large, whereas fixation is slow if the fraction of \(A\) is small. This scenario occurs for the coordination game. In the absence of zealots, the same game shows bistability such that the fixation to the unanimity of \(A\) or that of \(B\) occurs fast (Antal and Scheuring 2006). Third, for a selection strength smaller than a threshold value, the fixation is fast for any payoff matrix. In the absence of zealots, the dependence of the mean fixation time on \(N\) for large \(N\) values is completely determined by the signs of \(a-c\) and \(b-d\) (Antal and Scheuring 2006). Therefore, the scaling of the mean fixation time on \(N\) is independent of the selection strength because manipulating the selection strength does not change the sign of the effective \(a-c\) or \(b-d\) value. If the payoff matrix is given in the slow fixation regime, the fixation is exponentially slow even for a small selection strength. In contrast, in the presence of zealots, slow fixation can be accelerated if we lessen the selection strength.

Mobilia examined the prisoner’s dilemma game with cooperation facilitators (Mobilia 2012). A cooperation facilitator was assumed to cooperate with cooperators and not to play with defectors. The cooperation facilitator and zealous cooperator in the present study are common in that they never change the strategy. However, they are different. First, zealous cooperators are embedded in a well-mixed population such that they myopically cooperate with defectors as well as cooperators. Second, the ordinary players may imitate the zealous cooperator’s strategy (i.e., cooperation). In contrast, players do not imitate the cooperation facilitator’s strategy (i.e., cooperation) in Mobilia’s model. As a consequence, cooperation does not always fixate in his model.

Examination of the case of imperfect zealots, in which zealots change the strategy with a small probability (Masuda 2012), warrants future work.

References

Altrock PM, Traulsen A (2009) Fixation times in evolutionary games under weak selection. New J Phys 11:013012

Altrock PM, Gokhale CS, Traulsen A (2010) Stochastic slowdown in evolutionary processes. Phys Rev E 82:011925

Altrock PM, Traulsen A, Reed FA (2011) Stability properties of underdominance in finite subdivided populations. PLOS Comput Biol 7:e1002260

Antal T, Scheuring I (2006) Fixation of strategies for an evolutionary game in finite populations. Bull Math Biol 68:1923–1944

Assaf M, Mobilia M (2010) Large fluctuations and fixation in evolutionary games. J Stat Mech 2010:P09009

Assaf M, Mobilia M (2012) Metastability and anomalous fixation in evolutionary games on scale-free networks. Phys Rev Lett 109:188701

Ewens WJ (2010) Mathematical population genetics I. Theoretical introduction. Springer, New York

Fu F, Rosenbloom DI, Wang L, Nowak MA (2011) Imitation dynamics of vaccination behaviour on social networks. Proc R Soc B 278:42–49

Galam S, Jacobs F (2007) The role of inflexible minorities in the breaking of democratic opinion dynamics. Physica A 381:366–376

Hauert C, Doebeli M (2004) Spatial structure often inhibits the evolution of cooperation in the snowdrift game. Nature 428:643–646

Van Kampen NG (2007) Stochastic processes in physics and chemistry, 3rd edn. Elsevier, Netherlands

Krapivsky PL, Redner S, Ben-Naim E (2010) A kinetic view of statistical physics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kreindler GE, Young HP (2013) Fast convergence in evolutionary equilibrium selection. Games Econ Behav 80:39–67

Liu XT, Wu ZX, Zhang L (2012) Impact of committed individuals on vaccination behavior. Phys Rev E 86:051132

Masuda N (2012) Evolution of cooperation driven by zealots. Sci Rep 2:646

Maynard Smith J (1982) Evolution and the theory of games. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mobilia M (2003) Does a single zealot affect an infinite group of voters? Phys Rev Lett 91:028701

Mobilia M (2012) Stochastic dynamics of the prisoner’s dilemma with cooperation facilitators. Phys Rev E 86:011134

Mobilia M, Petersen A, Redner S (2007) On the role of zealotry in the voter model. J Stat Mech: P08029

Moran PAP (1958) Random processes in genetics. Proc Cambridge Philos Soc 54:60–71

Nowak MA, Sasaki A, Taylor C, Fudenberg D (2004) Emergence of cooperation and evolutionary stability in finite populations. Nature 428:646–650

Nowak MA (2006) Evolutionary dynamics. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, MA

Redner S (2001) A guide to first-passage processes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Singh P, Sreenivasan S, Szymanski BK, Korniss G (2012) Accelerating consensus on coevolving networks: the effect of committed individuals. Phys Rev E 85:046104

Sugden R (1986) The economics of rights, co-operation and welfare. Blackwell, New York

Taylor C, Fudenberg D, Sasaki A, Nowak MA (2004) Evolutionary game dynamics in finite populations. Bull Math Biol 66:1621–1644

Traulsen A, Pacheco JM, Nowak MA (2007) Pairwise comparison and selection temperature in evolutionary game dynamics. J Theor Biol 246:522–529

Traulsen A, Shoresh N, Nowak MA (2008) Analytical results for individual and group selection of any intensity. Bull Math Biol 70:1410–1424

Wu B, Altrock PM, Wang L, Traulsen A (2010) Universality of weak selection. Phys Rev E 82:046106

Xie J, Sreenivasan S, Korniss G, Zhang W, Lim C, Szymanski BK (2011) Social consensus through the influence of committed minorities. Phys Rev E 84:011130

Acknowledgments

We thank Bin Wu for carefully reading the manuscript. NM acknowledges the support provided through Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 23681033) from MEXT, Japan, the Nakajima Foundation, CREST JST, and the Aihara Innovative Mathematical Modelling Project, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the “Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST Program),” initiated by the Council for Science and Technology Policy (CSTP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Derivation of Eq. (6)

Denote by \(P_i(t)\) the probability that the random walker starting from state \(i\) at time 0 is absorbed to state \(N\) at time \(t\). The normalization is given by \(\sum ^{\infty }_{t=0} P_i(t) = 1\). It should be noted that \(P_N(0)=1\) and \(P_N(t)=0\) (\(t\ge 1\)). The mean fixation time when \(i\) ordinary players initially select strategy \(A\) is given by

It should be noted that \(t_N = 0\).

\(P_i(t)\) satisfies the recursion relation given by

By multiplying both sides of Eq. (43) by \(t\) and taking the summation over \(t\), we obtain

In terms of \(\sigma _i \equiv t_i-t_{i+1}\), Eq. (44) can be rewritten as

The solution of Eq. (45) is given by

where \(0\le i\le N-1\) and \(q_i\) is given by Eq. (7).

We set \(i=0\) in Eq. (44) and use \(T_0^- = 0\) to obtain

Therefore, we obtain

Using Eq. (48), we reduce Eq. (46) to

The mean fixation time is given by

Appendix B: Classification of the deterministic dynamics induced by the biased random walk

1.1 B.1 When \(a-b-c+d < 0\)

We obtain \(\mathrm{d}^2f(y)/\mathrm{d}y^2<0\) for \(a-b-c+d < 0\). Because

where we used the assumption \(a>0\) in Eq. (51), we distinguish the following two cases. If \(c < (m+1)a\), \(f(y)> 0\) is satisfied for \(0\le y\le 1\), yielding case (i) in the main text. If \(c > (m+1)a\), a certain \(y^*_1 (0<y^*_1<1)\) exists such that \(f(y)>0\) for \(0\le y<y^*_1\), and \(f(y)<0\) for \(y^*_1 < y\le 1\). Therefore, case (ii) occurs.

1.2 B.2 When \(a-b-c+d > 0\)

We obtain \(\mathrm{d}^2f(y)/\mathrm{d}y^2>0\) for \(a-b-c+d > 0\). In this situation, Eq. (51) holds true.

If \(f(1) < 0\), i.e., \(c > (m+1)a\), a certain \(y^*_1\) (\(0<y^*_1<1\)) exists such that \(f(y)>0\) for \(0\le y<y^*_1\), and \(f(y)<0\) for \(y^*_1 < y\le 1\). Therefore, case (ii) occurs.

Suppose that \(f(1) > 0\), i.e., \(c<(m+1)a\). To analyze this case, let us write

where

-

(i)

If \(\tilde{y} \le 0\), i.e., \(2ma+(-m+1)b-mc-d\ge 0\), we obtain \(f(y) \ge f(0) > 0\) for \(y\ge 0\). Therefore, case (i) occurs.

-

(ii)

If \(\tilde{y} \ge 1\), i.e., \(-(2m+2)a+(m+1)b+(m+2)c-d\ge 0\), then \(f(y) \ge f(1) > 0\), yielding case (i).

-

(iii)

If \(0 < \tilde{y} < 1\), we have the following two subcases:

-

(a)

If \(D = \left[ 2ma+(1-m)b-mc-d\right] ^2 - 4m(ma+b)(a-b-c+d) >0\), \(f(y)=0\) has two solutions \(0< y^*_1 < y^*_2 < 1\). In the deterministic dynamics driven by the bias \(T_i^+-T_i^-\), \(y^*_1\) and \(y^*_2\) are stable and unstable, respectively. Therefore, case (iii) occurs.

-

(b)

If \(D\le 0\), we obtain \(f(y) \ge 0\) for all \(0\le y<1\), where the equality holds true only when \(D=0\) and \(y=\tilde{y}\). Therefore, case (i) occurs.

-

(a)

1.3 B.3 When \(a-b-c+d = 0\)

The quadratic term in \(f(y)\) disappears when \(a-b-c+d = 0\). The classification of the dynamics in this case coincides with that for \(a-b-c+d < 0\).

Appendix C: Derivation of \(\tilde{q}(y)\)

To derive the relationship \(q_i = \left[ \tilde{q}(i/N)\right] ^N\), we write

where \(y =i/N\) and \(y^{\prime }=k/N\). Because the integral on the right-hand side of Eq. (55) is independent of \(N\), we obtain \(q_i = \left[ \tilde{q}(y)\right] ^N\). It should be noted that \(\tilde{q}(0)=1\) is consistent with \(q_0=1\).

Appendix D: Steepest descent method

As done in Antal and Scheuring (2006), we use the steepest descent method to evaluate \(\sum ^{N-1}_{k=i^*}(q_{N-1}/q_k)\) in Eq. (26) as follows:

where \(\tilde{q}(y^*) = \min _{0\le y <1}\tilde{q}(y)\). We approximate the integral by a Gaussian integral to obtain

with \(F(y^{\prime })=\ln \left[ \tilde{q}(y^{\prime })/\tilde{q}(y^*)\right] \) and \(\lambda =1/N\) such that

Appendix E: Weak selection introduced via an exponential function leads to fast fixation

Assume that the fitness of an A and B player is given by Eqs. (35) and (36), respectively. Then, we obtain

If \(T_i^-/T_i^+ < 1\), i.e.,

holds true for any \(i\) (\(1\le i\le N-1\)) and \(N\), the fixation occurs fast (i.e., \(t_0\propto N\ln N\)). By substituting \(y=i/N\) and \(m=M/N\) in Eq. (60) and ignoring \(O(N^{-1})\) terms, we obtain

Because the right-hand side of Eq. (61) is positive, there exists \(\beta _\mathrm{c}>0\) such that \(t_0\propto N\ln N\) when \(0\le \beta <\beta _\mathrm{c}\). It should be noted that, in contrast to the assumption throughout the present article, \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(d\) are allowed to be negative in the present analysis because \(f_i\) and \(g_i\) given by Eqs. (35) and (36) are positive irrespective of the \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(d\) values.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakajima, Y., Masuda, N. Evolutionary dynamics in finite populations with zealots. J. Math. Biol. 70, 465–484 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00285-014-0770-2

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00285-014-0770-2