Abstract

The aim of the study was to present the classification of anatomical variations of the stomach, based on the radiological and historical data. In years 2006–2010, 2,034 examinations of the upper digestive tract were performed. Normal stomach anatomy or different variations of the organ shape and/or topography without any organic radiologically detectable gastric lesions were revealed in 568 and 821 cases, respectively. Five primary groups were established: abnormal position along longitudinal (I) and horizontal axis (II), as well as abnormal shape (III) and stomach connections (IV) or mixed forms (V). The first group contains abnormalities most commonly observed among examined patients such as stomach rotation and translocation to the chest cavity, including sliding, paraesophageal, mixed-form and upside-down hiatal diaphragmatic hernias, as well as short esophagus, and the other diaphragmatic hernias, that were not found in the evaluated population. The second group includes the stomach cascade. The third and fourth groups comprise developmental variations and organ malformations that were not observed in evaluated patients. The last group (V) encloses mixed forms that connect two or more previous variations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Classic anatomical textbooks describe the stomach as the most dilated part of the digestive tract, located beneath the diaphragm in the left hypochondriac and epigastric region of the abdominal cavity [20, 30, 32]. Its shape and position are strongly associated with organogenesis. Any developmental abnormality of the organ itself or nearby located viscera and peritoneum, as well as their vessels and nerves may influence stomach morphology [3, 20, 26, 29, 30]. The final topography depends also on contents of the stomach and surrounding viscera, respiratory phase, age and body type of the individual. The empty organ is characterized by a cylindrical form with a well-formed anterior and posterior wall, lesser and greater curvature as well as fundus, cardia, body and pylorus (Figs. 1a, 2). In distended one, the anterior wall increases the area attached to the abdominal wall. During inspiration the organ is displaced downward, while elevated in expiration. Any abnormal fluid accumulation in the pleural and peritoneal cavity may change the stomach shape as well. Heavily build hypersthenic individuals with short thorax and long abdomen are likely to have stomach that is placed in higher position and more transversally. In persons with a slender asthenic physique, the stomach is located lower and more vertical. More vertical position and slightly left organ translocation—secondary to a relatively large liver—are typical of young children, in particular in newborns [30].

Diagrams with the most common, anatomical variances of the stomach: typical shape of the stomach (a), malrotation (b), sliding hiatal hernia (c), paraesophageal hiatal hernia (d), mixed-form hiatal hernia (e), upside-down hernia (f), congenital short esophagus (g), cascade (h), lack of the whole organ (i), lack of the fundus (j), short body (k), advanced enlargement (l), congenital gastroduodenal (m) and gastroileal (n) fistula

Classical anatomical description presented above, is not always seen in clinical practice. Different variations of the typical shape of the stomach are frequent. The aim of the study was to present classification of the shape and position of the unoperated stomach.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted on the retrospective data collected during various radiological examinations taken in 2006–2010 in the Second Radiological Department of the First University Hospital, Medical University of Lublin, Poland. All patients were sent for the checkup for various medical reasons with empty stomach. The examination was performed using Siregraph CF-System (Siemens, Germany) during single- or double-contrast fluoroscopy. Barium sulfuricum suspension (TERPOL, Poland) or Prontobario HD (Bracco S.P.A., Italy) was applied as a positive contrast in unoperated patients. Water-soluble contrasts such as Gastrografin (Berlimed S.A. Poligono Industrial Schering AG; Leverkusen, Germany) or Uropolinum (Zakłady Farmaceutyczne POLPHARMA; Starogard Gdanski, Poland) were administered for operated patients. Stomach air or pretreatment with Dougas (Bracco S.P.A., Italy) was used as a source of the negative contrast. Each patient was typically examined in Trendelenburg position, followed by supine, semirecumbent, antero-posterior and lateral erect position. Any other positions were used when needed. Single and serial pictures with acquisition time one up to 4–5 pictures per second were stored on the hard disc.

The classification was established exclusively for patients without any organic radiologically detectable stomach lesions, i.e., severe gastric inflammations, ulcer disease, neoplasms, etc. Five primary groups of the organ shape and topography were established: abnormal position along it longitudinal (I) and horizontal axis (II), as well as abnormal shape (III) and connections (IV) or mixed forms (V).

Obtained results were evaluated only qualitatively, since data were collected at a hospital that is highly specialized in esophageal and stomach surgery and the group of examined patients’ does not cover the general population.

Results

During evaluated period, 2,034 examinations of the upper part of digestive tract were performed. From among the whole group 1,389 patients passed the criteria of the study. Normal stomach anatomy was observed in 568 cases, while in 821 patients different variations of the organ shape and topography were reveled.

A regular, physiological position of the stomach—as presented at the introduction—was the most commonly observed among all the examined individuals (Figs. 1a, 2). Abnormal anatomical variances were seen less frequently. In unoperated patients the two main groups of the stomach variations were established: (I) abnormal positions along the longitudinal axis of the organ, and (II) abnormal positions along various horizontal axes (Table 1; Fig. 1b–n). Two additional groups, i.e. (III) abnormal shape of the organ, (IV) abnormal congenital connections of the stomach could also be added, however, they were not observed in our department and they do not pass the criteria of “healthy” organ. The last group (V) contains mixed forms, which pass criteria two or more primary groups (I–IV).

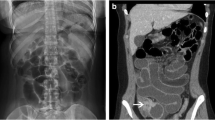

The first group included the stomach rotation (Ia), and translocation to the chest cavity (Ib). Different degrees of the stomach rotation were easily seen when position of the pylorus and the lesser and greater curvatures were examined (n = 84). In the extreme situation, a frontward (n = 3/84) and backward (n = 11/84) direction of the lesser curvature was found (Figs. 1b, 3). However, the most common type of the anomaly in the first group was the sliding hiatal diaphragmatic hernia (n = 522) (Figs. 1c, 4a). Less frequently, the paraesophageal hiatal (n = 12) (Figs. 1d, 4b), mixed-form (n = 43) (Figs. 1e, 4c) and upside-down hernias were found (n = 37) (Figs. 1f, 4d). The congenital short esophagus (Fig. 1g) and other diaphragmatic hernias of the stomach were not revealed, although all of them could be added to the Ib group.

The second group contains stomach cascade of different stages (n = 80) (Figs. 1h, 5a). Furthermore, the upside-down diaphragmatic hernia (n = 12/37) with both cardia and pylorus in the infradiaphragmatic position (Fig. 1f) could be included to this group as well.

The third group contains congenital abnormal shape of the organ i.e. lack of the whole organ (Fig. 1i), lack of the fundus (Fig. 1j), short stomach body (Fig. 1k) and prominent organ enlargement (dilatation) (Fig. 1l).

All the abnormal congenital connections of the stomach were enclosed in the fourth group. According to the available literature, the most common fistulas are gastroduodenal (Fig. 1m), gastrointestinal (Fig. 1n), gastrocolic and gastrocutaneous.

The last group (V) contains mixed forms. Such abnormalities were seen in 44 patients with a cascade and malrotation or different types of diaphragmatic hernias (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

The currently presented classification seems to be the first that clearly and completely describes anatomical positions of the stomach. Similar classifications were not available in the world literature.

Among all the examined patients with anatomical variances of the stomach, the most common position was the hiatal hernia (about 60–75% depends of the year). However, such high incidence cannot be regarded as typical for the Polish and even local population, while the study was performed in the University Hospital with a Surgical Department that is highly specialized in the esophageal and stomach surgery and is referential for the south-east part of Poland. Moreover, some patients were admitted to the hospital with previous, well-documented diagnosis and additional radiological examinations were not performed.

Since the first description in 1926 [2], confirmed by later studies, translocations of the stomach along its long axis is divided into sliding, paraesophageal and mixed-form hiatal diaphragmatic hernia, as well as a congenital short esophagus.

The sliding hiatal diaphragmatic hernia is the most common type seen on the level of esophageal hiatus and is characterized by the direct dislocation of the stomach cardia into the posterior mediastinum. Such anomaly is observed in 80–90% of the abnormal translocations of the stomach through this foramen [23]. Epidemiological data suggest a strong geographical and socioeconomic-dependent distribution of the disease. Its highest prevalence was observed in well-economically developed communities of the North America and the Europe, where the incidence reaches 15–20% of the adults. It increases with age, from 10% in patients younger than 40 years to 70% in those older than 70 years [41, 47]. However, much lower incidence (0.3%) was presently found among 637,518 Americans by Hauer-Jensen et al. [21]. Contrary to those data, the disease is extremely rare in rural African communities. Such abnormal stomach position was revealed in four out of 1,030 examined Nigerians [4], one of 1,000 Kenyans [44] and one of 700 Tanzanians [19]. A low incidence was also reported throughout India, the Middle East and East Asia [9]. A strong environmental influence, with no or low genetic predisposition was proved by observation of the same incidence of the sliding hiatal hernia in Afro-Americans and Caucasian Americans [9]. It was also noted in two different Korean studies taken at a 35-year interval, characterized by extremely high positive socioeconomic changes of the country. Kim [25] found only 14 cases (1.4%) of the hernia among 1,000 examined patients, while in 1999 it was revealed in 41 (4.1%) out of 1,010 individuals [46]. Unlike other investigations, Boghratian et al. [7] observed male gender predilection in patients with hiatal hernia after examination of 4,700 Iranians. Moreover, the disease is observed mostly in older patients. However, due to the abnormal prenatal enlargement of the esophageal hiatus, a congenital sliding hiatal hernia may also be found but have to be differ from the short esophagus (see below) [34]. Furthermore, the hernia is commonly associated with diverticular disease and less frequently with cholelithiasis—Sait’s triad [21]. Also obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), advanced renal insufficiency, prolapse of the mitral valve [22] and persistent high intraabdominal pressure increase risk of the hernia [13, 37, 45]. High abdominal pressure was also found as one of the leading factors in other diseases associated with a hiatal hernia, i.e., inguinal hernia and prolapse of pelvic organs [13, 39]. As a consequence of herniation, a relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, wider cardiac angle and esophageal empting impairment increase the possibility of the gastro-esophageal reflux. On the other hand, the hiatal hernia and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GRED) itself are risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus, chronic blood loss and iron-deficiency anemia [5, 36], vertebral fracture [31], atherosclerosis, as well as esophageal and laryngeal neoplasms [5].

The second type of hiatal hernia is the paraesophageal one, morphologically characterized by the normal position of the cardia but the adjusted part of the stomach fundus is slided superiorly through the esophageal hiatus. The paraesophageal and mixed-form hernias—that combined sliding and paraesophageal features—have not been extensively epidemiologically studied. Both types (II and III according to Akerlund) are observed less often [23] nevertheless their surgical treatment significantly increases morbidity and mortality [12, 40]. In advanced stage of the mixed-form hernia, the whole stomach is located intrathoracically (upside-down stomach hernia). Nowadays, prevalence of such anomaly increases especially in symptomatic patients [35]. According to the currently published data, a frequency of the intrathoracic stomach is about 52 per one million persons. The disease is strongly associated with age, and affects especially elderly people (>65 year), more commonly blacks than whites [35].

The last type of the hiatal hernia is the congenital short esophagus. According to the classic description by Peters [34], it significantly differs from the acquired type that is always associated with the sliding diaphragmatic hernia (Table 2). The incidence of the developmental anomaly is estimated as 3–14% of all patients that undergo antireflux surgery [14] and 0.084% of the general population [34].

All anomalies listed above have to be distinguished from congenital or acquired diaphragmatic hernia, in which the stomach with or without other abdominal organs enters the thoracic cavity through diaphragmatic openings other than the esophageal hiatus. Most frequently they are enlarged sternocostal and lumbocostal triangles or pathological openings that are secondary to diaphragmatic injuries or their abnormal development. The congenital diaphragmatic hernia occurs one in every 2,500 live births, and in about 30% of spontaneous abortions [42]. The posterolateral (Bochdalek) and anterolateral (Morgagni) types are found in 70 and 27%, respectively. In remaining cases (2–3%), the opening is located on the level of the central tendon (septum-transversum type). From among all the Bachdalek’s hernias, the left (85%) and bilateral (2%) ones normally include the stomach [17, 18]. Experimental data suggest that, prenatal exposure to herbicide (i.e., nitrofene), corticosteroids and non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitors increase the risk of the anomaly. All those xenobiotics may disturb organogenesis by the influence on vascular development of stomach, surrounding viscera and abdominal wall, including diaphragm [8, 10, 11, 18, 29, 33]. However, those findings were not entirely confirmed in humans [24], in which a strong correlation with genetic (Sonic Hedgehog—Shh gene pathways) and environmental factors were found [11]. Furthermore, the disease is more common in males and whites. It commonly complicated respiratory distress, pulmonary hypoplasia, and less frequently, pleural effusion, esophageal reflux, patent ductus arteriosus, atrial and ventricular septal defects, as well as congenital infections, acidosis and neonatal jaundice [28].

The second subgroup of abnormal position of the stomach along the long axis of the organ is various degree rotations of the stomach, which are secondary to the malrotation of the gastrointestinal tract that normally took place in an early stage of the prenatal life [16, 30]. They include: lack, incomplete (<90o) or over-rotation (>90o) of the stomach. When the lesions are limited to the stomach or other part of the gut, they may be asymptomatic [1]. Clinically, abnormal rotation of the stomach without its obstruction is also called volvulus. However, the malrotation of the organ could also be associated with various developmental anomalies of the stomach (i.e., congenital paraesophageal hernia), and constitute a part of serious congenital syndromes (e.g., gastric organo-axial, heterotaxy, Meckel–Gruber syndrome) [6, 15, 43]. Additionally, in Meckel–Gruber syndrome, the stomach has a longitudinal, intestine-like shape, without the proper fundus [15].

The group of abnormal positions among horizontal axis contains gastric cascades characterized by a biloculation of the gastric cavity into a ventral (corpus and antrum) and a dorsal (fundus) recess [27]. Such abnormal position may be congenital, functional or secondary to organic disorders of the stomach and surrounding organs, mostly peritoneal adhesions. Due to lack of any specific symptoms its incidence is unknown.

Stomach shape may be also affected by the feeding habits. A chronic large amount of food taken day after day may increase the organ volume. Unlike enlargement after vagotomy, such “physiologically” large stomach may be reversible [16, 30, 38].

In conclusion four primary groups of stomach variations were established: abnormal position along longitudinal (I) and horizontal axis (II), as well as abnormal shape (III) and stomach connections (IV). The first group contained the stomach rotation and translocation to the chest cavity, including sliding, paraesophageal, mixed-form and upside-down hiatal diaphragmatic hernias, short esophagus, and the other diaphragmatic hernias. The second group included the stomach cascade of different stages. The third and fourth ones comprised developmental variations and organ malformations. The last group (V) enclosed mixed forms that connect two or more previous variations.

References

Abdullah F, Zhang Y, Sciortino C, Camp M, Gabre-Kidan A, Price MR, Chang DC (2009) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: outcome review of 2, 173 surgical repairs in US infants. Pediatr Surg Int 25:1059–1064

Akerlund A (1926) Hernia diafragmatica hiatus oesophagei vom anatomischen und rontgenologischen Gesichts-punkt. Acta Radiol 6:3–22

Apaydin N, Uz A, Elhan A, Loukas M, Tubbs RS (2008) Does an anatomical sphincter exist in the distal esophagus? Surg Radiol Anat 30:11–16

Bassey OO, Eyo EE, Akinhanmi GA (1977) Incidence of hiatus hernia and gastro-oesophageal reflux in 1030 prospective barium meal examinations in adult Nigerians. Thorax 32:356–359

Belhocine K, Galmiche JP (2009) Epidemiology of the complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis 27:7–13

Biyyam DR, Dighe M, Siebert JR (2009) Antenatal diagnosis of intestinal malrotation on fetal MRI. Pediatr Radiol l39:847–849

Boghratian AH, Hashemi MH, Kabir A (2009) Gender-related differences in upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings: an assessment of 4,700 cases from Iran. J Gastrointest Cancer 40:83–90

Burdan F (2005) Comparison of developmental toxicity of selective and non-selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in CRL:(WI)WUBR Wistar rats-DFU and piroxicam study. Toxicology 211:12–25

Burkitt DP (1981) Hiatus hernia: is it preventable? Am J Clin Nutr 34:428–431

Cook JC, Jacobson CF, Gao F, Tassinari MS, Hurtt ME, DeSesso JM (2003) Analysis of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug literature for potential developmental toxicity in rats and rabbits. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 68:5–26

Costlow RD, Manson JM (1981) The heart and diaphragm: target organs in the neonatal death induced by nitrofen (2, 4-dichlorophenyl-p-nitrophenyl ether). Toxicology 20:209–227

Dahlberg PS, Deschamps C, Miller DL, Allen MS, Nichols FC, Pairolero PC (2001) Laparoscopic repair of large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg 72:1125–1129

De Luca L, Di Giorgio P, Signoriello G, Sorrentino E, Rivellini G, D’ Amore E, De Luca B, Murray JA (2004) Relationship between hiatal hernia and inguinal hernia. Dig Dis Sci 49:243–247

Demeester SR, Demeester TR (2003) Editorial comment: the short esophagus: going, going, gone? Surgery 133:364–367

Ergür AT, Taş F, Yildiz E, Kiliç F, Sezgin I (2004) Meckel–Gruber syndrome associated with gastrointestinal tractus anomaly. Turk J Pediatr 46:388–392

Freeny PC, Stevenson GW (1994) Margulis and Burhenne’s alimentary tract radiology, 5th edn. Mosby, St. Luis, pp 318–372

Gedik E, Girgin S, Tuncer MC, Onat S, Avci A, Karabulut O (2010) Bochdalek hernia with concomitant partial situs inversus in an adult. Folia Morphol 69:119–122

Gedik E, Tuncer MC, Onat S, Avci A, Tacyildiz I, Bac B (2011) A review of Morgagni and Bachdalek Hernis in adults. Folia Morphol 70:5–12

Gerech P (1965) Radiological analysis of lesions of the upper intestinal tract during a fur-year period in Africans in Tanganyika (now Tanzania). East Afr Med J 42:106–116

Gray H, Pick TP, Howden R (1974) Anatomy, descriptive and surgical. Running Press, Philadelphia

Hauer-Jensen M, Bursac Z, Read RC (2009) Is herniosis the single etiology of Saint’s triad? Hernia 13:29–34

Horváth M (1997) Association of hiatal hernia with mitral valve prolapse. Eur J Pediatr 156:35–36

Johnson DA, Ruffin WK (1996) Hiatal hernia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 6:641–666

Keijzer R, Puri P (2010) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg 19:180–185

Kim EH (1964) Hiatus hernia and diverticulum of the colon. Their low incidence in Korea. N Engl J Med 271:764–768

Koyuncu E, Malas MA, Albay S, Cankara N, Karahan N (2009) The development of fetal pylorus during the fetal period. Surg Radiol Anat 31:335–341

Kose M, Pekcan S, Kiper N, Akgul S, Cobanoglu N, Yalcin E, Dogru D, Ozcelik U, Haliloglu M, Senocak ME (2009) Gastric organo-axial malrotation coexisting respiratory symptoms. Eur J Pediatr 168:491–494

Lally KP (2002) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Curr Opin Pediatr 14:486–490

Loukas M, Wartmann CT, Louis RG Jr, Tubbs RS, Ona M, Curry B, Jordan R, Colborn GL (2007) The clinical anatomy of the posterior gastric artery revisited. Surg Radiol Anat 29:361–366

Moore KL, Dalley AF (2006) Clinical oriented anatomy, 5th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Nagahara A, Ohtaka K, Shimada Y, Asaoka D, Kurosawa A, Osada T, Kawabe M, Hojo M, Yoshizawa T, Watanabe S (2008) Presence of vertebral fractures is highly associated with hiatal hernia and reflux esophagitis in Japanese elderly people. Intern Med 47:1451–1455

Narkiewicz O, Morys J (2010) Anatomia Człowieka. PZWL, Warszawa

Neville HL, Jaksic T, Wilson JM, Lally PA, Hardin WD Jr, Hirschl RB, Lally KP (2003) Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Bilateral congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 38:522–524

Peters PM (1958) The congenital short oesophagus. Thorax 13:1–11

Polomsky M, Hu R, Sepesi B, O’Connor M, Qui X, Raymond DP, Litle VR, Jones CE, Watson TJ, Peters JH (2010) A population-based analysis of emergent vs. elective hospital admissions for an intrathoracic stomach. Surg Endosc 24:1250–1255

Ruhl CE, Everhart JE (2001) Relationship of serum leptin concentration and other measures of adiposity with gallbladder disease. Hepatology 34:877–883

Sakaguchi M, Oka H, Hashimoto T, Asakuma Y, Takao M, Gon G, Yamamoto M, Tsuji Y, Yamamoto N, Shimada M, Lee K, Ashida K (2008) Obesity as a risk factor for GERD in Japan. J Gastroenterol 43:57–62

Schouten R, Freijzer PL, Greve JW (2007) Laparoscopic sleeve resection of a recurrent gastric cascade: a case report. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17:307–310

Segev Y, Auslender R, Feiner B, Lissak A, Lavie O, Abramov Y (2009) Are women with pelvic organ prolapse at a higher risk of developing hernias? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 20:1451–1453

Sihvo EI, Salo JA, Räsänen JV, Rantanen TK (2009) Fatal complications of adult paraesophageal hernia: a population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 137:419–424

Sleisenger MH, Sauders WB (1997) Gastrointestinal and liver disease, 6th edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 457–466

Stege G, Fenton A, Jaffray B (2003) Nihilism in the 1990s: the true mortality of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics 112(3 Pt 1):532–535

Thacker D, Gruber PJ, Weinberg PM, Cohen MS (2009) Heterotaxy syndrome with mirror image anomalies in identical twins. Congenit Heart Dis 4:50–53

Whittaker LR (1966) A review of a series of radiological examinations of the upper alimentary tract in African patients. East Afr Med J 43:336–340

Wilson LJ, Ma W, Hirschowitz BI (1999) Association of obesity with hiatal hernia and esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 94:2840–2844

Yeom JS, Park HJ, Cho JS, Lee SI, Park IS (1999) Reflux esophagitis and its relationship to hiatal hernia. J Korean Med Sci 14:253–256

Zeppa R, Polk HC Jr (1971) Surgery for esophageal hiatus hernia. J Fla Med Assoc 58:26–28

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Bogumil Goral and Robert Klepacz for drawings and preparing all illustrations for publications, respectively.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Burdan, F., Rozylo-Kalinowska, I., Szumilo, J. et al. Anatomical classification of the shape and topography of the stomach. Surg Radiol Anat 34, 171–178 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-011-0893-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-011-0893-8