Abstract

Background

Whilst injuries are a major cause of disability and death worldwide, a large proportion of people in low- and middle-income countries lack timely access to injury care. Barriers to accessing care from the point of injury to return to function have not been delineated.

Methods

A two-day workshop was held in Kigali, Rwanda in May 2019 with representation from health providers, academia, and government. A four delays model (delays to seeking, reaching, receiving, and remaining in care) was applied to injury care. Participants identified barriers at each delay and graded, through consensus, their relative importance. Following an iterative voting process, the four highest priority barriers were identified. Based on workshop findings and a scoping review, a map was created to visually represent injury care access as a complex health-system problem.

Results

Initially, 42 barriers were identified by the 34 participants. 19 barriers across all four delays were assigned high priority; highest-priority barriers were “Training and retention of specialist staff”, “Health education/awareness of injury severity”, “Geographical coverage of referral trauma centres”, and “Lack of protocol for bypass to referral centres”. The literature review identified evidence relating to 14 of 19 high-priority barriers. Most barriers were mapped to more than one of the four delays, visually represented in a complex health-system map.

Conclusion

Overcoming barriers to ensure access to quality injury care requires a multifaceted approach which considers the whole patient journey from injury to rehabilitation. Our results can guide researchers and policymakers planning future interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Each year, one billion people sustain injuries requiring health care. Injury is a leading cause of disability and associated with over five million deaths each year [1]. Injuries account for more deaths that tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV combined, and 90% of injury deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2]. Road traffic collisions (RTC) may be the third leading global cause of death by 2030 [3]. Halving the number of global deaths and injuries due to RTCs is a key Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3.6) [4].

Rwanda has one of the highest incidence of injuries in the world [5] and has committed to reduce morbidity and mortality due to injuries [6]. Nevertheless, in 2012, 22% of all deaths in Rwanda’s capital Kigali were from injury, with RTCs the most common mechanism [7]. In 2017, 10% of DALYS and 9% of deaths were injury related [8].

The three delays framework was developed to understand factors driving avoidable maternal deaths. It has been widely adopted in research on barriers in access to care [9]. The delays are: 1. delays in seeking care; 2. delays in reaching care; and 3. delays in receiving quality health care at a facility [10]. The framework has also been used to show delays in accessing injury care are implicated in up to 36% of injury deaths [11, 12]. Much injury care research in LMICs has focused on delay three; assessing and improving care provision in facilities. This neglects many injured people that never reach a facility, potentially 40% of avoidable mortality [11]. We adapted the three delays model, by including a fourth delay, remaining in care, distinguishing between initial receipt of emergency care and ongoing care provided as follow-up or rehabilitation [13]. This study aimed to use this four delay framework to describe delays and identify and prioritise barriers to accessing quality injury care in Rwanda [11, 12] and to visually represent the complex inter-relationships between them.

Methods

Setting

Rwanda is a small landlocked country in east-Africa with a low Human Development Index (HDI), ranking 158 of 189 countries [14]. Following significant economic growth since the 1994 Genocide against Tutsis, the health system has experienced major improvements. Initiatives include a national health insurance policy, performance-based financing of health programmes, and village community health workers [15, 16]. Despite improvements, health care investment in Rwanda remains insufficient [14, 17]. The Rwandan government has committed to reducing injury morbidity and mortality [6].

Stakeholder workshop

A national stakeholder concept mapping workshop was held over 2 days in Kigali, May 2019, bringing together multi-sectoral participants involved in injury care in Rwanda. Through this workshop, this study aimed to:

-

1.

Identify barriers in access to injury care in Rwanda.

-

2.

Prioritize identified barriers for future research and intervention.

-

3.

Schematically map identified barriers to the four delays framework.

-

4.

Scope existing literature for injury care studies in Rwanda and relate findings to the workshop identified barriers.

Participants

Participants were purposively invited from a broad range of professional backgrounds, with expertize to understand barriers to quality care from point of injury to return to optimal function. Invitations were sent to; community health providers; police, fire and rescue; telecommunications providers; prehospital care providers (Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Division/SAMU (Service d’Aide Médicale d’Urgence); secondary care injury-care providers; government ministry representatives, including ministry of health; medical students; information and technology representatives; injury and disability researchers; physiotherapists; health insurance providers; and international Rwandan-based NGOs.

Identifying and prioritising barriers

The workshop began with an introduction to the four delays framework and an update on injury care and developments in Rwanda. Participants were divided into four groups, each focused on one conceptual delay to injury care, based on their interests and expertize.

First, groups brainstormed barriers at each of their assigned delays. If identified barriers were thought to affect additional delays, this was discussed. Second, participants ranked barriers into roughly equal groups of high, medium, and low priority based upon their impact and feasibility of addressing them with interventions. After each group discussion, findings were presented to the whole workshop. Questions and wider discussion followed with opportunity to adjust findings based on consensus.

Third, consensus on the highest four priority barriers across all delays was achieved through sequential smartphone voting using menti.com™ application [18]. Three rounds of anonymous voting were undertaken. In round one, each participant was asked to indicate their top four out of the all barriers ranked as high priority. Those with ≤5% of votes were removed. In round two, participants again selected their four highest priority barriers. If four barriers were clearly forerunners, these were to be selected and voting stopped. If fewer than four barriers were clear forerunners, those that were clear high priorities were removed and participants asked to vote on the remainder of the barriers. Participants debated results between voting stages and justified their choices.

Scoping literature search

A scoping review searched PubMed in July 2019 for published studies relating to barriers to injury care in Rwanda. Broad search strings were [Rwanda AND (Trauma OR Injury)], (Rwanda AND delays), and (Rwanda AND barriers). There were no defined year limits or language restrictions for publications. A single author (JW) screened the articles and extracted data. Any articles of any study type that reported evidence on barriers to access to care were eligible for inclusion. Available published evidence from within the Rwandan health system was tabulated against each identified barrier.

Analysis

In order to schematically represent barriers to accessing injury care as a complex health-system problem, the barriers proposed at the workshop were synthesized into overarching categories by authors based on established health system frameworks [19, 20]. These were also mapped to their respective delay, illustrating where they impact access to injury care. A visual map was created combining workshop discussion results with the authors’ knowledge and scoping review findings. The map was adjusted iteratively by discussion amongst the authors (MLO, JW, DN, and JD). Findings were fed back to all workshop participants for comment by email correspondence and face to face discussion, where practical; the map was further adjusted after this feedback.

Ethical considerations

This priority setting workshop did not involve patients and did not use any personal identifying information. Ethical Review Board permission was therefore not required.

Results

Thirty-four participants from different stakeholder groups attended the workshop. There was broad representation from professionals with knowledge and experience according to the different delays (“Appendix 1”). In brainstorming discussions, 42 barriers were generated across each delays. These barriers were subsequently assigned priorities of low (11/42), medium (12/42), and high (19/42) (Table 1).

Barriers securing the majority vote after the first two rounds were; 1. “Training and retention of specialist staff”, 2. “General and health education/awareness”, and 3. “Low referral trauma centre geographical coverage” (Table 2). To discriminate between the remaining 6 barriers, a third round of voting was undertaken. The barrier “Lack of protocol for bypass to referral centre” was selected.

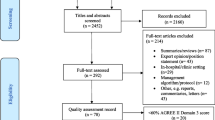

Scoping review

The PubMed search identified 231 articles. Following title screening, 46 abstracts were identified as potentially relevant. Three duplicates were removed. Of the 43 unique abstracts, full text review identified 27 considered relevant to inform the understanding of barriers driving delays to injury or non-injury care within Rwanda. 16/27 articles directly studied injury whilst 11/27 were not injury related. 23/27 studies were from Rwanda only, whilst 4/27 incorporated other countries. Two studies reported an intervention, the remainder being observational. Both intervention studies were before and after studies; one evaluated the impact of delivering Advanced Trauma Life Support training on care process and patient outcome measures at a single centre [21]. Another reported a multi-centre multinational implementation of the WHO trauma care checklist for which 1/11 centres was based in Rwanda [22].

For 26/42 barriers to injury care identified in the stakeholder workshop, there was at least one published study which provided corroborating evidence of delays to access to care for injury (Table 3). Two barriers identified in our workshop had studies evidencing them delaying care for other health problems in Rwanda. Supporting evidence from the published literature was not found for 14 workshop identified barriers. Of 19 high-priority barriers, 14 were supported by at least one injury related publication including all four highest priority barriers. The remaining five high-priority barriers lacking published evidence were “religious beliefs/community decision making”, “lack of ambulance fleet maintenance”, “inadequate ambulance equipment maintenance and stocking”, “lack of private investment in ambulances” and “lack of public awareness of ambulance fees” (Table 3).

Visualization of the barriers

The barriers were divided into five overarching categories; individual factors, societal factors, financial factors, general infrastructural factors, and health-system infrastructural factors. More granular categories were avoided to ensure the visual representation was interpretable. Barriers at each delay and across all the delays combined are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Iterative refining and revision of the barriers resulted in 54 barriers within these five categories. Some barriers are shown acting distinctly within just one delay whilst others impact across multiple. For example, “trauma location” is only linked to delay 2, whilst “health insurance availability, uptake and cost” was identified to have substantial impacts upon multiple delays (“Appendix 2”). The inter-relationships between barriers along with the theorized direction of impact is shown using arrows (Figs. 1 and 2).

Discussion

This study is the first that we are aware of to identify all barriers to accessing injury care from the point of injury to being rehabilitated to maximal function in a low-income country, to visually represent their inter-relationships, prioritize them for future research and intervention, and identify which had been previously investigated in scientific studies. We utilized a four delay extension to the three delays framework, well established for assessing barriers to maternal, neonatal, and child health [47,48,49,50,51]. The three delays has shown utility to describe, classify and assess LMIC emergency and trauma systems [11, 12, 52]. The fourth delay has also been previously conceptualized as the delay in communities taking responsibility for avoidable mortality [53]. However, we preferred the definition of delay to remaining within the health care system [13]. By including it, our findings can inform rehabilitation service development in Rwanda, potentially benefiting 70,000 Rwandans living with injury-related musculoskeletal impairment, of whom almost half have not accessed adequate treatment [29].

Multiple barriers were identified across all delays in our study, falling under different (and sometimes multiple) overarching categories, inter-related with each other in a highly complex manner. Minimal research on interventions to address these barriers has been carried out in Rwanda, and identified studies mostly focused on tertiary facility-level care. The four highest priority barriers selected by workshop participants covered barriers impacting across all four delays.

There is a global health care workforce crisis, with workforce density particularly low in Sub-Saharan Africa [54, 55]. It is therefore understandable that the “training and retention of specialist staff” was given high priority for action by the workshop participants. International migration of health care workers is substantial. Over 40% Rwandan-born physicians practised in high-income countries in 2000 [56]. However, skilled health workforce density (physicians, nurses, and midwives) increased from 0.48 to 0.79 per 1000 population from 2005 to 2015 [57], though still considerably lower than higher income countries [58]. Workforce retention is likely particularly important in rural areas, where most Rwandans live [59, 60]. Emergency Medicine specialty training implemented in Kigali has shown mortality benefit at the University Teaching Hospital—Kigali [61]; the effects of such training programs in other locations needs to be investigated.

“General and health education/awareness” was a high-priority barrier not specifically concerning facility-level care. Zambian community members similarly identified improving emergency condition recognition and bystander first aid provision as important health-system intervention targets [62]. Health care literacy has similarly been found a barrier to LMIC injury care though Verbal Autopsy analysis and stakeholder Delphi studies [11, 12].

Most injury related procedures in University Teaching Hospital, Kigali, are for patients transferred from outside of Kigali [44]. “Low referral trauma centre geographical coverage” enabling provision of advanced trauma care has been shown to be sub-optimal elsewhere. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery identified that 5 billion people, globally, lacked timely access to quality surgical care [9] including trauma treatment through emergency laparotomy and open fracture. In only 16 of 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 80% of the population can access to public hospitals providing emergency care within 2 h [63]. However, such studies use geospatial mapping data that may not represent actual experienced travel time, especially in the rainy season [64].

“Lack of protocols for bypass to referral centre” to enable injury patients to be treated at the right hospital at the right time was the final barrier prioritized in our workshop. Developing bypass protocols can enable urgent cases to access more advanced injury care quickly, whilst limiting overburdening higher-level facilities with lower priority cases. This is recommended by the WHO as best practice for prehospital trauma care systems [65]. There is evidence from high-income countries showing lower risk of death for those transported directly to a Level 1 trauma centre [66, 67]. Although, comparable evidence from sub-Saharan Africa is lacking.

Health systems have been described as complex adaptive systems, nonlinear, counter-intuitive, and resistant to change [68]. Outside of trauma care, visual representations and interpretations of complex phenomena have been advocated to aid understanding such systems [69]. By visually representing the barriers and the associations between them within a four delays framework, our study can support researchers and policy makers understanding the complexity of Rwanda and other countries’ trauma care health systems and critically evaluating potential targets and consequences of interventions.

Our study has limitations. Only 34 participants were included and wider participation could have identified more barriers. Most participants were health care providers perhaps more inclined to prioritize barriers to receiving care. Patients or patient advocates were not included, missing their perspective or perceived priorities. Neither were police representatives included, often first to an injury scene. The schematic representation of the refined barriers was undertaken by the writing group members (MLO, JW, DN, and JD). Feedback from workshop participants was obtained, but the distant approach may have limited meaningful participation. Published evidence was scoped from one database and focused on Rwanda only. Expanding search terms, including additional databases and broadening geographic scope may yield additional corroborating evidence. However, an extensive systematic literature search was beyond the aims of this study.

This is the first workshop aiming to capture the complexity of barriers to access of quality injury care in Rwanda, and as far as we are aware, in any LMIC. Previous studies related to injuries in Rwanda have focused on disease burden and epidemiology, commonly related to road traffic collisions specifically. Although some groups were not represented in our workshop, we purposively invited people with research or work experience linked to each delay. Therefore, we trust the workshop captured most barriers linked to the different delays, and the richness and complexity of the data are clearly illustrated in the visual representation of barriers.

Conclusion

In this study, we have identified, prioritized, and visually represented barriers in access injury care within Rwanda. These manifold barriers are complexly interconnected. Theoretically, therefore, addressing one of the highly prioritized barriers could impact positively on other barriers and delays. This theoretical understanding, along with stakeholder expressed priorities, can guide both researchers and policy makers alike in planning future research and interventions to improve injury care for the people of Rwanda and other LMICs.

Change history

02 May 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06584-z

References

Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I et al (2016) The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Injury Prev J Int Soc Child Adolesc Injury Prev 22:3–18

Gosselin RA, Spiegel DA, Coughlin R et al (2009) Injuries: the neglected burden in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 87:246–246a

Mathers CD, Loncar D (2006) Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3:e442

World Health Organization (2015) Sustainable development goal 3: health

WHO (2018) Global status report on road safety 2018

Brown H (2007) Rwanda’s road-safety transformation. Bull World Health Orgn 85:421–500

Kim WC, Byiringiro JC, Ntakiyiruta G et al (2016) Vital statistics: estimating Injury Mortality in Kigali, Rwanda. World J Surg 40:6–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3258-3

Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH et al (2018) Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 392:1736–1788

Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L et al (2015) Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet (Lond, Engl) 386:569–624

Thaddeus S, Maine D (1994) Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 38:1091–1110

Edem IJ, Dare AJ, Byass P et al (2019) External injuries, trauma and avoidable deaths in Agincourt, South Africa: a retrospective observational and qualitative study. BMJ Open 9:e027576

Whitaker J, Nepogodiev D, Leather A et al (2019) Assessing barriers to quality trauma care in low and middle-income countries: A Delphi study. Injury 51:278–285

Roder-DeWan S, Gupta N, Kagabo DM et al (2019) Four delays of child mortality in Rwanda: a mixed methods analysis of verbal social autopsies. BMJ Open 9:e027435

UNDP (2018) Human development indices and indicators: 2018 statistical update Rwanda

Gatera M, Bhatt S, Ngabo F et al (2016) Successive introduction of four new vaccines in Rwanda: high coverage and rapid scale up of Rwanda’s expanded immunization program from 2009 to 2013. Vaccine 34:3420–3426

Logie DE, Rowson M, Ndagije F (2008) Innovations in Rwanda’s health system: looking to the future. Lancet (Lond, Engl) 372:256–261

UNICEF (2018) Health budget brief: investing in children’s health in Rwanda 2018/2019, 2018

Mentimeter. www.mentimeter.com. Accessed 14 May 2020

World Health Organisation (2007) Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. World Health Organisation, Geneva

Atun R, Aydın S, Chakraborty S et al (2013) Universal health coverage in Turkey: enhancement of equity. The Lancet 382:65–99

Petroze RT, Byiringiro JC, Ntakiyiruta G et al (2015) Can focused trauma education initiatives reduce mortality or improve resource utilization in a low-resource setting? World J Surg 39:926–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2899-y

Lashoher A, Schneider EB, Juillard C et al (2017) Implementation of the World Health Organization trauma care checklist program in 11 centers across multiple economic strata: effect on care process measures. World J Surg 41:954–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3759-8

Zafar SN, Canner JK, Nagarajan N et al (2018) Road traffic injuries: cross-sectional cluster randomized countrywide population data from 4 low-income countries. Int J Surg (Lond, Engl) 52:237–242

Mpirimbanyi C, Abahuje E, Hirwa AD et al (2019) Defining the three delays in referral of surgical emergencies from district hospitals to University Teaching Hospital of Kigali, Rwanda. World J Surg 10:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-04991-3

Petroze RT, Joharifard S, Groen RS et al (2015) Injury, disability and access to care in Rwanda: results of a nationwide cross-sectional population study. World J Surg 39:62–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2544-9

Musafili A, Persson LA, Baribwira C et al (2017) Case review of perinatal deaths at hospitals in Kigali, Rwanda: perinatal audit with application of a three-delays analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 17:85

Lorent N, Mugwaneza P, Mugabekazi J et al (2008) Risk factors for delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis at a referral hospital in Rwanda. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tubercul Lung Dis 12:392–396

Ruktanonchai CW, Ruktanonchai NW, Nove A et al (2016) Equality in maternal and newborn health: modelling geographic disparities in utilisation of care in five East African Countries. PLoS ONE 11:e0162006

Matheson JI, Atijosan O, Kuper H et al (2011) Musculoskeletal impairment of traumatic etiology in Rwanda: prevalence, causes, and service implications. World J Surg 35:2635–2642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1293-2

Umuhoza C, Karambizi AC, Tuyisenge L et al (2018) Caregiver delay in seeking healthcare during the acute phase of pediatric illness, Kigali, Rwanda. Pan Afr Med J 30:160

Pace LE, Mpunga T, Hategekimana V et al (2015) Delays in breast cancer presentation and diagnosis at two rural cancer referral centers in Rwanda. Oncologist 20:780–788

Ntaganira J, Muula AS, Siziya S et al (2009) Factors associated with intimate partner violence among pregnant rural women in Rwanda. Rural Remote Health 9:1153

Niyitegeka J, Nshimirimana G, Silverstein A et al (2017) Longer travel time to district hospital worsens neonatal outcomes: a retrospective cross-sectional study of the effect of delays in receiving emergency cesarean section in Rwanda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17:242

Aluisio AR, Umuhire OF, Mbanjumucyo G et al (2017) Epidemiologic characteristics of pediatric trauma patients receiving prehospital care in Kigali, Rwanda. Pediatric Emerg Care 35:630–636

Nkusi AE, Muneza S, Nshuti S et al (2017) Stroke burden in Rwanda: a multicenter study of stroke management and outcome. World Neurosurg 106:462–469

Bayitondere S, Biziyaremye F, Kirk CM et al (2018) Assessing retention in care after 12 months of the Pediatric Development Clinic implementation in rural Rwanda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatrics 18:65

Patel A, Krebs E, Andrade L et al (2016) The epidemiology of road traffic injury hotspots in Kigali, Rwanda from police data. BMC Public Health 16:697

Krebs E, Gerardo CJ, Park LP et al (2017) Mortality-associated characteristics of patients with traumatic brain injury at the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali, Rwanda. World Neurosurg 102:571–582

Chokotho L, Jacobsen KH, Burgess D et al (2016) A review of existing trauma and musculoskeletal impairment (TMSI) care capacity in East, Central, and Southern Africa. Injury 47:1990–1995

Calland JF, Holland MC, Mwizerwa O et al (2014) Burn management in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for implementation of dedicated training and development of specialty centers. Burns J Int Soc Burn Injuries 40:157–163

Tuyisenge G, Hategeka C, Luginaah I et al (2018) Continuing professional development in maternal health care: barriers to applying new knowledge and skills in the hospitals of Rwanda. Matern Child Health J 22:1200–1207

Nkurunziza T, Toma G, Odhiambo J et al (2016) Referral patterns and predictors of referral delays for patients with traumatic injuries in rural Rwanda. Surgery 160:1636–1644

Nkusi AE, Muneza S, Hakizimana D et al (2016) Missed or delayed cervical spine or spinal cord injuries treated at a Tertiary Referral Hospital in Rwanda. World Neurosurg 87:269–276

Ntakiyiruta G, Wong EG, Rousseau MC et al (2016) Trauma care and referral patterns in Rwanda: implications for trauma system development. Can J Surg J 59:35–41

Atijosan O, Simms V, Kuper H et al (2009) The orthopaedic needs of children in Rwanda: results from a national survey and orthopaedic service implications. J Pediatr Orthop 29:948–951

Kikuchi K, Poudel KC, Muganda J et al (2012) High risk of ART non-adherence and delay of ART initiation among HIV positive double orphans in Kigali, Rwanda. PloS ONE 7:e41998

Combs Thorsen V, Sundby J, Malata A (2012) Piecing together the maternal death puzzle through narratives: the three delays model revisited. PLoS ONE 7:e52090

Wilmot E, Yotebieng M, Norris A et al (2017) Missed opportunities in neonatal deaths in Rwanda: applying the Three delays model in a cross-sectional analysis of neonatal death. Matern Child Health J 21:1121–1129

Waiswa P, Kallander K, Peterson S et al (2010) Using the three delays model to understand why newborn babies die in eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health TM & IH 15:964–972

Upadhyay RP, Rai SK, Krishnan A (2013) Using three delays model to understand the social factors responsible for neonatal deaths in rural Haryana, India. J Trop Pediatr 59:100–105

Pajuelo MJ, Anticona Huaynate C, Correa M et al (2018) Delays in seeking and receiving health care services for pneumonia in children under five in the Peruvian Amazon: a mixed-methods study on caregivers’ perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res 18:149

Calvello EJ, Skog AP, Tenner AG et al (2015) Applying the lessons of maternal mortality reduction to global emergency health. Bull World Health Organ 93:417–423

MacDonald T, Jackson S, Charles M-C et al (2018) The fourth delay and community-driven solutions to reduce maternal mortality in rural Haiti: a community-based action research study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18:254

Kempthorne P, Morriss WW, Mellin-Olsen J et al (2017) The WFSA global anesthesia workforce survey. Anesth Analg 125:981–990

O’Flynn E, Andrew J, Hutch A et al (2016) The specialist surgeon workforce in East, Central and Southern Africa: a situation analysis. World J Surg 40:2620–2627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3601-3

Clemens MA, Pettersson G (2008) New data on African health professionals abroad. Hum Resour Health 6:1

Republic or Rwanda Ministry of Health Health (2019) Labour market analysis report

Bank TW Physicians (per 1,000 people)

Odhiambo J, Rwabukwisi FC, Rusangwa C et al (2017) Health worker attrition at a rural district hospital in Rwanda: a need for improved placement and retention strategies. Pan Afr Med J 27:168

Serneels P, Montalvo JG, Pettersson G et al (2010) Who wants to work in a rural health post? The role of intrinsic motivation, rural background and faith-based institutions in Ethiopia and Rwanda. Bull World Health Organ 88:342–349

Aluisio AR, Barry MA, Martin KD et al (2019) Impact of emergency medicine training implementation on mortality outcomes in Kigali, Rwanda: an interrupted time-series study. Afr J Emerg Med 9:14–20

Broccoli MC, Cunningham C, Twomey M et al (2016) Community-based perceptions of emergency care in Zambian communities lacking formalised emergency medicine systems. Emerg Med J 33:870–875

Ouma PO, Maina J, Thuranira PN et al (2018) Access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015: a geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. Lancet Glob Health 6:e342–e350

Holmer H, Bekele A, Hagander L et al (2019) Evaluating the collection, comparability and findings of six global surgery indicators. BJS (British Journal of Surgery) 106:e138–e150

World Health Organisation (2005) Prehospital trauma care systems

Mans S, Reinders Folmer E, de Jongh MAC et al (2016) Direct transport versus inter hospital transfer of severely injured trauma patients. Injury 47:26–31

Haas B, Gomez D, Zagorski B et al (2010) Survival of the fittest: the hidden cost of undertriage of major trauma. J Am Coll Surg 211:804–811

de Savigny D, Adam T (2009) Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. alliance for health policy and systems research. World Health Organisation, Geneva

Adam T (2014) Advancing the application of systems thinking in health. Health Res Policy Syst 12:50

Funding

Funding for the project was received from The University of Birmingham’s Institute for Global Innovation. Prof Belli is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre (SRMRC). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD, MLO, JW, JC, and A Bekele conceived of the idea and organized the workshop. MLO, JW, DN, JD, JC, A Bekele. JS, AR, and A Belli led themes for discussion at the meeting. MLO, JW, DN, and JD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in discussions and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict interest

Antonio Belli is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre (SRMRC). All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

This study did not involve patients and did not use any personal identifying information. Ethical Review Board permission was therefore not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Odland, M.L., Whitaker, J., Nepogodiev, D. et al. Identifying, Prioritizing and Visually Mapping Barriers to Injury Care in Rwanda: A Multi-disciplinary Stakeholder Exercise. World J Surg 44, 2903–2918 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05571-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05571-6