Abstract

Background

A robust health care system providing safe surgical care to a population can only be achieved in conjunction with access to competent surgical personnel. It has been reported that 5 billion people do not have access to safe, affordable surgical and anaesthesia care when needed. This study aims to fill the existing gap in evidence by quantifying shortfalls in trained personnel delivering safe surgical and anaesthetic care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) according to the type of health care facility.

Methods

We conducted secondary analysis of 1323 health facilities, in 35 low- and middle-income countries using facility-based cross-sectional data from the World Health Organization Situational Analysis Tool to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care.

Results

The majority of surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs was provided by general doctors (range 13.8–41.1%; mean 27.1%). Non-physicians made up a significant proportion of the surgical workforce in LMICs. 26.76% of the surgical and anaesthetic workforce was provided by clinical medical officers and nurses. Private/NGO/mission hospitals, large, well-resourced institutions had the highest proportion of surgeons compared to any other type of health care facility at 27.92%. This compares to figures of 18.2 and 19.96% of surgeons at health centres and subdistrict/community hospitals, respectively, representing the lowest level of health facility.

Conclusions

We highlight the significant proportion of non-physicians delivering surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs and illustrate wide variations according to the type of health care facility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A robust health care system providing safe surgical care to a population can only be achieved in conjunction with access to competent surgical personnel. It has been reported that the poorest third of the world’s population obtain only 3.5% of surgical operations conducted globally and that 5 billion people do not have access to safe, affordable surgical and anaesthesia care when needed [1, 2]. This is, in part, due to shortfalls in trained personnel, infrastructure and political priority [3, 4].

There is a common misconception that improving access to safe surgical and anaesthetic care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is too expensive. However, multiple studies dismiss this notion, demonstrating the significant cost-effectiveness of surgical interventions in LMICs when compared to standard national health interventions [5, 6] and call for its acknowledgement as a critical component of the post-2015 global health agenda [7, 8].

The World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC) in December 2005: a global forum convening stakeholders representing health authorities, public health experts, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil and professional societies and individuals collaborating towards improving access to safe surgical and anaesthetic care in a global setting [9]. In 2007, GIEESC members developed the standardized WHO Situational Analysis Tool (SAT): a cross-sectional survey form used as an evidence-based tool to quantify surgical and anaesthetic capacity within participating facilities in LMICs. The SAT has been validated for assessing surgical capacity from various levels of health care facilities in LMICs and has been used to collect data from 55 LMICs from December 2007 through the present [10].

This study focuses on filling the existing gap in evidence by quantifying shortfalls in trained personnel delivering safe surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs, using the WHO Situational Analysis Tool. We aim to describe these shortfalls according to various levels of health care facility, namely health centres, subdistrict/community hospitals, district/rural hospitals, general hospitals, provincial hospitals and private/non-governmental organization (NGO)/mission hospitals.

Materials and methods

Data collection

The standardized WHO Situational Analysis Tool (SAT) to assess access to emergency and essential surgical care was developed by the WHO Global Initiative for Essential and Emergency Surgical Care research group in November 2007. The WHO SAT includes 108 data points addressing four core sections: (1) infrastructure and health facility demographics; (2) health care personnel; (3) availability of surgical interventions; and (4) availability of surgical equipment and supplies. The availability of surgical equipment and supplies is based on the WHO Essential and Emergency Equipment List.

Data were collected by Ministries of Health, WHO country offices and by Global Initiative for Essential and Emergency Surgical Care (GIEESC) representatives in individual countries visiting the health facilities. These data were entered into the WHO EESC global database at the WHO headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, from December 2007 through the present. However, only data entered into the database between December 2007 and August 2014 were included for the purposes of this paper.

Data analysis

Countries providing assessments on less than 3 health care facilities were excluded from the aggregated data. This was in line with previous studies employing the WHO tool [3]. Health care facilities with incomplete data points for “Introduction” in section (infrastructure) and “Materials and methods” in section (human resources) of the WHO SAT were excluded.

Health care facilities included health centres, subdistrict/community hospitals, district/rural hospitals, general hospitals, provincial hospitals and private/non-governmental organization (NGO)/mission hospitals.

Ethical approval was deemed not necessary to be obtained for this study, as patient information was not included.

Results

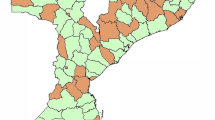

All entries from the WHO SAT database are listed below with the number of health care facilities completing the SAT (Table 1). Those highlighted in green are LMICs providing assessments on less than 3 health care facilities and were, therefore, excluded from the aggregated data. There were a total of 1323 health care facilities from 35 countries which met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Types of health care facility

There were a total of 1323 facilities surveyed from 35 LMICs (Fig. 2). The majority of facilities were district/rural hospitals (24.6%), followed by health centres (24%), private/NGO/mission hospitals (17.8%), subdistrict/community hospitals (16.7%), general hospitals (10.4%) and provincial hospitals (6.4%) as shown in Fig. 3.

Personnel

To assess shortfalls in trained personnel delivering surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs, we looked at the different types of human resources present across all types of health care facility included in analysis (Fig. 4). General doctors providing surgery constituted the bulk of trained personnel providing surgical and anaesthetic care across all types of health care facility (27.1%), followed by surgeons (23.2%), nurses/clinical medical officers (CMO) providing anaesthesia (16.8%), obstetricians/gynaecologists (11.04%), clinical medical officers providing surgery (10%), anaesthesiologists (6.2%) and finally general doctors providing anaesthesia (5.8%).

Human resources according to types of health care facility

From a total of 1323 health care facilities included in analysis, the bulk of personnel providing surgical and anaesthetic care were general doctors providing surgery (range 13.8–41.1%; mean 27.1%), surgeons (range 12.21–27.9%; mean 23.2%) and nurses/clinical medical officers providing anaesthesia (range 12.1–29.6%; mean 16.8%) (Figs. 4, 5).

This majority of personnel providing surgical and anaesthetic care varied considerably according to the type of health care facility. Health centres, representing the lowest level of health care facility, had surgeons representing 20% of their human resources, compared to a figure of 27.9% at private/NGO/mission hospitals: typically well-equipped institutions (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates that the majority of surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs is provided by general doctors (range 13.8–41.1%; mean 27.1%). However, the team providing such care is highly varied, with surgeons, nurses, clinical medical officers (CMOs), obstetricians/gynaecologists and anaesthesiologists making significant contributions to the surgical and anaesthetic team also. If we combine the proportion of CMOs providing surgery with nurses/CMOs providing anaesthesia, this figure stands at 26.76%. Therefore, non-physicians make up a significant proportion of the surgical workforce in LMICs.

Shortage of surgical staff in LMICs has partly been addressed through international agencies and programmes run by local or expatriate surgeons [11]. This is reflected in the data for private/NGO/mission hospitals: large, well-resourced institutions with the highest proportion of surgeons compared to any other type of health care facility at 27.92% (Fig. 5). This compares to figures of 18.2 and 19.96% of surgeons at health centres and subdistrict/community hospitals, respectively, representing the lowest level of health facility (Fig. 5).

The International Classification of Health Workers (ICHW) has indicated that certain non-surgical personnel, including general medical practitioners and nursing professionals, have the scope to carry out certain surgical procedures within their role [12]. Programmes to train such personnel in surgical procedures, such as caesarean section and abscess drainage, have been adopted in certain countries, including Tanzania, Malawi and the Democratic Republic of Congo [11]. Compared with physician programmes, these can be highly cost-effective, have favourable outcomes and have better recruitment and retention of staff [13]. To ensure concerns about the quality and safety of care are allayed, standardised competencies and training programmes for non-physicians providing surgical and anaesthetic care need to be established.

A critical step in helping to define scalable solutions for the provision of quality surgical and anaesthesia care has been the recent launch of the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery (LCoGS). A study conducted by the LCoGS analysed national data from WHO member countries on the number of specialist surgeons, anaesthetists and obstetricians (SAOs) per 100,000 population and its correlation with the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births [14]. From this, the LCoGS introduced a surgical preparedness metric, suggesting a target for a global workforce of SAOs to be set between 20 and 40 per 100,000 of a population in order to provide the world’s missing surgical procedures [14]. How this target relates to non-specialist surgical providers is unclear. This study aims to fill in the existing gap in evidence by highlighting the significant proportion of non-physicians providing surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs.

This study has several limitations. The WHO Situational Analysis Tool database represents a sample of convenience and is therefore susceptible to selection bias. The health care facilities in the data are not necessarily geographically or demographically representative of their country. Furthermore, although the number of health care personnel at each health care facility is available, how they relate to care of patients is unclear. The data points collected from the WHO SAT are unable to differentiate which kind of physicians provided surgical or anaesthetic care. A further study could disaggregate this further, demonstrating what kinds of physicians provide care in these categories.

It is important to note that there is a wide variety of health care structures across LMICs. The data collected in this study focussed more on health worker count than health systems. A potential area for future research would separate LMICs to examine whether there are different perspectives in different parts of the world with regards to non-physician providers administering surgical and/or anaesthetic care.

We highlight the significant proportion of non-physicians delivering surgical and anaesthetic care in LMICs and illustrate wide variations according to the type of health care facility.

References

Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD et al (2008) An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 372:139–144

Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L et al (2015) Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 386:569–624

Vo D, Cherian MN, Anesthesia Bianchi S (2012) Anesthesia Capacity in 22 Low and Middle Income Countries. J Anesth Clin Res 3:4

Farmer PE, Kim JY (2008) Surgery and Global Health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg 32:533–536. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9525-9

Grimes CE, Henry JA, Maraka J et al (2014) Cost-effectiveness of surgery in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. World J Surg 38:252–263. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9525-9

Bae JY, Groen RS, Kushner AL (2011) Surgery as a public health intervention: common misconceptions versus the truth. Bull World Health Organ 89:394

McCord C, Chowdury Q (2003) A cost effective small hospital in Bangladesh: what it can mean for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 81:83–92

Gosselin RA, Thind A, Bellardinelli A (2006) Cost/DALY averted in a small hospital in Sierra Leone: what is the relative contribution of different services? World J Surg 30:505–511. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0609-5

World Health Organization, 2015. WHO global imitative for emergency and essential surgical care. [ONLINE] http://www.who.int/surgery/globalinitiative/en/. Accessed 03 Nov 15

Osen H, Chang D, Choo S et al (2011) Validation of the world health organization tool for situational analysis to assess emergency and essential surgical care at district hospitals in Ghana. World J Surg 35:500–504. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0918-1

Ozgediz D, Kijjambu S, Galukande M et al (2008) Africa’s neglected surgical workforce crisis. Lancet 371:627–628

World Health Organisation (2010) Classifying health workers: Mapping occupations to the international standard classification. [ONLINE] http://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/Health_workers_classification.pdf Accessed 04 Nov 15

Kruk M, Pereira C, Vaz F et al (2007) Economic evaluation of surgically trained assistant medical officers in performing major obstetric surgery in Mozambique. BJOG 114:1253–1260

Holmer H, Shrime M, Reisel JM et al (2015) Towards closing the gap of the global surgeon, anaesthesiologist, and obstetrician workforce: thresholds and projections towards 2030. Lancet 385(Suppl 2):S40

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheik Ali, S., Jaffry, Z., Cherian, M.N. et al. Surgical Human Resources According to Types of Health Care Facility: An Assessment in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. World J Surg 41, 2667–2673 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4078-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4078-4