Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate the acceptability of 14 days of self-quarantine and the positivity rate of pre-operative severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening for patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery.

Methods

The self-quarantine programme and pre-operative SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening were initiated for patients who were scheduled for admission later than 7 May 2020 for elective orthopaedic surgery on admission. On the day of admission, the patients declared compliance with self-quarantine regulations. The admission was refused in cases of non-compliance. After admission, the patients underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening. If PCR results were negative, isolation was terminated. If PCR results were positive, the surgery was postponed. If the patients had symptoms suspicious of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) after surgery, the PCR test was repeated.

Results

Overall, 308 patients (age: 63.2 ± 18.8 years, 197 female and 111 male) were scheduled for elective orthopaedic surgery. Two patients did not agree with the requirements of self-quarantine, and two other procedures were cancelled. No non-compliance was reported; thus, the completion rate of the self-quarantine programme was 304/308 (98.7%). Finally, 304 patients underwent PCR testing, and there were no positive PCR results. After cancellations of four operations due to reasons other than COVID-19, 300 surgical procedures were performed. No patients developed COVID-19 during hospitalisation.

Conclusions

Although this system is based on trusting the good behaviour of patients, accompanied by PCR screening, we believe that the results showed the efficacy of the system in safely performing orthopaedic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has globally threatened lives in the past several months. During the pandemic, healthcare systems were highly stressed and non-urgent elective surgery was postponed or cancelled to free up beds and medical staff for treating patients with COVID-19. With a decrease in the number of patients with COVID-19 and reduction of stress on the healthcare system, elective surgery has resumed.

Pre-operative screening of surgical patients for COVID-19 is currently recommended, although no universal guidelines exist [1]. One of the unfavourable features of COVID-19 is the existence of asymptomatic carriers; even in symptomatic patients, several days of the incubation period are required for symptom occurrence [2]. To avoid the admission of undiagnosed asymptomatic carriers, pre-operative universal screening is a reasonable option. Screening is highly beneficial for the patients themselves; a mortality rate of 20.5% in 34 elective procedures performed in China and 18.9% in 280 elective operations in an international cohort were reported within the incubation period of COVID-19 [3, 4]. Screening is also beneficial for hospital staff because transmission of the COVID-19 from patients to surgeons and other hospital staff has been reported [5,6,7]. Hence, the detection of asymptomatic patients before admission is highly desirable to protect both the medical staff and patients.

Repeated outbreaks of COVID-19 have been reported worldwide, and a resurge of infection has been reported in many countries. Japan has also experienced multiple outbreaks. To safely resume elective orthopaedic surgery in these difficult circumstances, our hospital conducted a single polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test pre-operative screening in combination with 14 days of self-quarantine before admission. This study aimed to evaluate the acceptance of pre-admission self-quarantine and PCR screening in patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery, the positivity rate of SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening after self-quarantine, and whether there was a patient diagnosed with COVID-19 after surgery.

Materials and methods

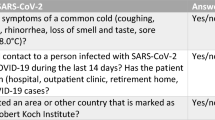

This study was a prospective case series under the approval of the ethics committee of our hospital. Informed consent from each patient was waived, and an opt-out was offered. The self-quarantine programme and pre-operative SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening (Fig. 1) were commenced for the patients who were scheduled for admission to a teaching hospital in Kyoto Japan later than 7th May 2020 after the five successive hospital holidays. All elective orthopaedic surgery was extracted from the electronic data registry in the medical record system and were prospectively included in this study. The elective surgery in this study included arthroplasties, non-urgent spine surgery, procedures for musculoskeletal tumours, and other elective orthopaedic operations for joints, peripheral nerves, tendons, and bones. Patients who underwent emergency or urgent surgery, such as trauma procedures, emergency spine operations, emergency tumour procedures, surgery for acute infection, or surgery for ischaemic conditions were excluded. Patients who denied participating in this prospective data collection were excluded, as were patients undergoing outpatient surgery under local anaesthesia. There was no exclusion due to the background or health condition of the patients.

Patients scheduled for elective surgery were asked to undergo two weeks of self-quarantine (Table 1). The patients were required to be admitted to the hospital one to five days before the surgery. On the day of admission, the patients declared that they had followed the self-quarantine regulations and had not had any symptoms or contact with COVID-19 patients. Admission was refused in the case of non-compliance. After admission, the patients were isolated in a private room and underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening using either a nasal swab or saliva, even when a patient had a recent negative PCR result. Additional radiological screening was not performed. Until the PCR results were known, they were treated as suspected COVID-19 patients, were isolated in the private room, and medical staff were required to wear personal protective equipment in the presence of these patients. If PCR results were negative, isolation was terminated. If PCR results were positive, the surgery was postponed, and the patients were kept isolated. The patients were followed up until discharge. If the patients had symptoms such as unexplained fever, respiratory tract symptoms, dysgeusia, or dysosmia that led to a suspicion of COVID-19, the PCR test was repeated with an adequate radiographic evaluation. If the patient came in contact with a person who was suspected with COVID-19, the PCR test was repeated even when the patient was asymptomatic.

PCR test

Samples were liquefied using semi-alkaline protease (Sputazyme; Kyokuto Pharmaceutical Industrial, Tokyo, Japan) before centrifuging at 20,000×g for two minutes. RNA was extracted from 140 μL of the supernatant of saliva samples or universal transport media for nasal swabs using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with RNA extraction controls, 5 μL of LightMix Modular EAV RNA Extraction Control (EAV; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) or 10 μL of MS2 phage (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and eluted in a final volume of 60 μL. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR was performed using N1, N2, and RNaseP (RP) internal control assays developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019-nCoV CDC EUA kit, obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) using a LightCycler 480 System II (Roche).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were employed. The following numbers were recorded: the scheduled elective orthopaedic surgery, acceptance or denial of the self-quarantine, compliance and non-compliance with the self-quarantine, admissions, total PCR screenings, positive and negative PCR results, surgery performed, suspected COVID-19 patients after surgery, and repetitive PCR tests after surgery. The data are expressed as actual counts, percentages, and means ± standard deviations for continuous values. The data were also analysed in subgroups according to age and sex. To answer the clinical questions in this study, (1) the rate of acceptance of pre-admission self-quarantine and PCR screening, (2) the PCR screening positivity rate, and (3) number of repetitive PCR and diagnoses of COVID-19 after elective surgery were obtained.

Results

The rate of acceptance of pre-admission self-quarantine and PCR screening

Between 7th May and 31st October 2020, 308 patients (age: 63.2 ± 18.8 years, 197 female and 111 male) were scheduled for elective orthopaedic surgery under general or spinal anaesthesia. Two patients cancelled the surgery because they did not agree with the requirements of self-quarantine and pre-operative PCR screening. The acceptance rate of the self-quarantine programme was 306 /308 (99.4%). Two surgical procedures were cancelled before admission due to reasons unrelated to COVID-19. On the day of admission (3.8 ± 1.2 days, minimum 1 day, maximum 5 days, prior to the surgery), 304 patients submitted the self-quarantine document, and no non-compliance was declared. Thus, the completion rate of the self-quarantine programme was 304 /308 (98.7%). The details are shown in Table 2 with subgroups according to age and sex.

The PCR-positive screening rate

Finally, 304 patients were admitted to the ward. All 304 patients underwent PCR testing, and there were no positive results after 0.7 ± 0.4 days (minimum 0 days, maximum 2 days) (Table 2). The surgery of three patients were cancelled after PCR sample collection because of personal reasons, and they were discharged. One operation was cancelled because of high fever due to otolaryngologic disease. For the remaining 300 patients who cleared two weeks of self-quarantine and had negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR results, orthopaedic surgery (111 arthroplasties, 46 musculoskeletal tumour surgeries, 45 spine operations, 35 hand and microscopic surgical procedures, 18 arthroscopic procedures, 16 knee and hip osteotomies for adults, 15 foot and ankle operations, and 14 other surgical procedures) were performed as scheduled.

The development of COVID-19 after elective surgery

There were no patients with unexplained fever or symptoms related to COVID-19 after surgery. SARS-CoV-2 PCR was not repeated for suspected symptoms of COVID-19; however, PCR was repeated for one patient with negative result because the patient had possible contact with COVID-19 patients. Thus, no patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 during hospitalisation.

Discussion

To protect patients and medical staff from COVID-19 and safely perform elective surgery, concentrated efforts should be made to not form clusters of patients undergoing elective surgery at the hospital. A high risk of exposure of healthcare workers to COVID-19 has been reported. Surprisingly, 19% of patients in the United States were identified as healthcare workers [7]. Infection transmission from surgical patients to medical staff was reported in China; six out of 51 surgeons, nine out of 38 ward nurses, and one out of nine anaesthesiologists who were exposed to surgical patients with COVID-19 were infected [5]. In a report of 26 orthopaedic surgeons, the suspected sites of exposure were general wards (79%), public places in the hospital (21%), operating theatre (13%), intensive care unit (4%), and outpatient clinic (4%) [6]. Thus, there is a high risk of infection transmission to medical staff from patients with COVID-19.

According to the international statement [8] and orthopaedic guidelines/recommendations [9, 10], elective surgery may be performed in cases of a continuous decrease in the number of patients with COVID-19 and sustained reduction in the incidence of new COVID-19 cases in the relevant geographic area for at least 14 days. The availability of sufficient facilities, beds, personal protective equipment, and most importantly, medical staff is essential. Japan has been combating several waves of COVID-19 by voluntary self-isolation of people without any enforcement, punishment, or lockdown of its cities (Fig. 2). Although a state of emergency was proclaimed in our prefecture on 7 April 2020 with the third highest number of COVID-19 infected people per million population in 47 prefectures, the number of new patients started decreasing in the middle of April, and the number of patients continued to decrease since the end of April. Overwhelming of hospitals because of the increase in infection was also avoided. With these local conditions, self-quarantine and pre-operative SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening were undertaken for patients undergoing elective surgery in the second week of May and continued until 31 October 2020.

The number of cases with COVID-19 in Japan from 16th January to 31st October 2020 [26]. A state of emergency was proclaimed in several metropolitan areas in Japan, including Kyoto on 6th April, and lifted 21st May 2020

Consensus has not yet been reached regarding the best screening method for elective orthopaedic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. To perform surgery without a definite screening method, the stratification approach for an elective surgery is advocated according to the priority of surgery, subspeciality, and risks of the patients [1]. The decision-making algorithm for risk stratification is also useful in deciding whether to perform elective surgery. [11]. Universal screening for essential orthopaedic surgery in New York in April 2020 showed a 12.1% COVID-19 positive rate, which included 58.3% asymptomatic patients [12]. Computed tomography (CT) screening for urgent elective surgery in the United Kingdom reported findings suggestive of COVID-19 in 13/156 (8%) patients, and COVID-19 was confirmed in two of these patients with an additional PCR test [13]. Although CT provides the most accurate diagnosis for COVID-19 pneumonia, the use of CT for universal screening may be impractical due to its high cost and radiation exposure [12, 14]. Other screening methods use antibody tests, but the presence of antibodies was <40% among patients within one week of onset [15]. Thus, antibody testing as a screening method in the early stages would result in false negatives. For the universal screening of patients for elective surgery, diagnosing as many asymptomatic patients as possible is desirable. The sensitivity of PCR is approximately 70–98%, and it seems reasonable for screening purposes [16]. In the recommendation of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association in May, both PCR tests and CT were recommended for screening [10]. Currently, the International Consensus Group (ICM) and Research Committee of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS), European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery & Arthroscopy (ESSKA), and European Hip and European Knee Society support the use of PCR for screening in cases of elective orthopaedic surgery [9, 17, 18].

The number of PCR tests is also important for effective screening. Given the reported false-negative rate of the PCR test for COVID-19 (2–30%) [16], repeat PCR testing may be justified. However, there is no consensus on repeating the PCR test for screening purposes. A recent study reported a 1.9% rate of positive PCR after initially negative PCR results and supports selective repeat PCR testing only when symptoms develop after a negative test, or in hospitalised patients with a high clinical suspicion for COVID-19 [19]. Another report also supports selective repeat of PCR tests only when patients exhibit typical CT findings of COVID-19 and does not recommend routine repetitive PCR only because of the possibility of false negatives [20]. We do not hesitate to perform a repeat PCR test in suspicious cases, but we now do not routinely repeat PCR for asymptomatic inpatients.

No patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 during hospitalisation after surgery. This may indicate that our self-quarantine with PCR screening safely blocked the admission of COVID-19 patients. We believe that self-quarantine is a crucial component of patient behaviour to prevent an increased risk of infection. The nosocomial spread of COVID-19 is not uncommon. In the worst-case scenario, asymptomatic but infected patients could become super spreaders, which may generate infection clusters in the hospital. In a recent calculation in the United Kingdom, the risk of patients with an undetected SARS-CoV-2 infection being inadvertently admitted for elective orthopaedic surgery was relatively low (0.07%, 1 in 1400) [21]; however, the best efforts should be taken to decrease this possibility. The self-quarantine programme is beneficial in decreasing the possibility of infection in patients scheduled to undergo elective surgery if all patients strictly obey the rules. It is important to make the patients aware that they are a potential source of bringing COVID-19 infection into the hospital, and they must reduce the exposure to COVID-19 as much as possible. Minimising the transmission of COVID-19 among healthcare workers is also a high priority. To this end, hospital staff have undergone selective PCR and antibody surveillance in conjunction with several behavioural protocols. They have been required to check their body temperature every day, to wear a mask whenever in the hospital, and to comply with strict hospital rules similar to the self-quarantine programme. By complying with self-quarantine, patients as well as medical staff protect the hospital from the undesirable spread of COVID-19.

A limitation is that this self-quarantine programme is based on the voluntary cooperation of the patients. Given the cooperative self-isolation of the majority of the Japanese population under the state of emergency, we believe that the majority of our patients would have adequately complied with the self-quarantine rules, which is critical for reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital. Additionally, in-hospital isolation with PCR screening could diagnose a small number of asymptomatic patients who could be sources of nosocomial infection. The small patient number was another limitation. Several studies have shown that patients with undiagnosed COVID-19 visit hospitals. During the explosive surge of COVID-19 in New York, 13.5% of women admitted for delivery in March were reported as SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive [22]. Universal screening at three children’s hospitals in the US reported an infection rate of 0.93% from 26 March to 22 April 2020 [23]. In Tokyo, 5.97% of asymptomatic patients receiving non-coronavirus-related treatments were confirmed to have SARS-CoV-2 infection by PCR tests between 13 April and 19 April 2020 [24]. In another screening study using antibody titres against SARS-CoV-2 in an outpatient clinic in Kobe from 31 March to 7 April 2020, 3.3% of the asymptomatic population showed positive results [25]. The PCR-positive rate in all populations in the Kyoto prefecture was 3.5% during the study period (Table 3) [26]. These results indicate that a small percentage of patients who visit hospitals may have SARS-CoV-2. Although this study did not include as many patients as reported in other multi-centre studies of universal screening [23, 27], zero PCR-positive results out of 304 tests may be meaningful to introduce this unique screening programme. Finally, this study did not include a control group. A control group without self-quarantine, or even without PCR screening, might be needed to scientifically prove the efficacy of our programme. However, to minimise the risk of the entry of COVID-19 to the ward and operation theatre, a combination of self-quarantine and pre-operative PCR was performed. A control group could not be prepared for ethical and safety reasons, as it might theoretically increase the risk of bringing COVID-19. Although this study did not include a control group, we believe that accumulating the results of various screening methods is important for determining the best screening method and formulating proper guidelines.

In conclusion, even though this system is based on trusting the good behaviour of patients, the results of this survey showed that self-quarantine accompanied by PCR screening is an effective method for safely performing orthopaedic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Availability of data and material

All raw data is available in hand of the corresponding author.

References

Massey PA, McClary K, Zhang AS, Savoie FH, Barton RS (2020) Orthopaedic surgical selection and inpatient paradigms during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28:436–450. https://doi.org/10.5435/jaaos-d-20-00360

Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, Azman AS, Reich NG, Lessler J (2020) The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med 172:577–582. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0504

Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, Chen C, Chen J, Mei W, Zhan LY, Jia Y, Zhang L, Liu D, Xia ZY, Xia Z (2020) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine 21:100331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331

COVIDSurg Collaborative (2020) Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet 396:27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31182-x

Hou J, Wan X, Shen Q, Zhu J, Leng Y, Zhao B, Xia Z, He Y, Wu Y (2020) COVID-19 infection, a potential threat to surgical patients and staff? A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 82:172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.08.037

Guo X, Wang J, Hu D, Wu L, Gu L, Wang Y, Zhao J, Zeng L, Zhang J, Wu Y (2020) Survey of COVID-19 disease among orthopaedic surgeons in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China. J Bone Joint Surg 102:847–854. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.00417

Bandyopadhyay S, Baticulon RE, Kadhum M et al (2020) Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 5:e003097. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003097

American College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Association of peri Operative Registered Nurses, and American Hospital Association (2020) Joint statement: roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://asprtracie.hhs.gov/technical-resources/resource/8722/joint-statem. Accessed 14 Sept 2020

Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Krueger CA, Chisari E, Citak M, Van Onsem S, Walter WL, International Consensus Group (ICM) and Research Committee of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (2020) Resuming elective orthopaedic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidelines developed by the International Consensus Group (ICM). J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:1205–1212. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.00844

Matsumoto M, Takeshita K, Ito J (2020) The Japanese of Orthopaedic Association. Recommendations for resuming orthopedic elective surgery; 2020/ 5/ 28. Available at: https://www.joa.or.jp/topics/2020/files/suggestions_for_resuming.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2020. (in Japanese)

Prakash L, Dhar SA, Mushtaq M (2020) COVID-19 in the operating room: a review of evolving safety protocols. Patient Saf Surg 14:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-020-00254-6

Gruskay JA, Dvorzhinskiy A, Konnaris MA, LeBrun DG, Ghahramani GC, Premkumar A, DeFrancesco CJ, Mendias CL, Ricci WM (2020) Universal testing for COVID-19 in essential orthopaedic surgery reveals a high percentage of asymptomatic infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.01053

Chetan MR, Tsakok MT, Shaw R, Xie C, Watson RA, Wing L, Peschl H, Benamore R, MacLeod F, Gleeson FV (2020) Chest CT screening for COVID-19 in elective and emergency surgical patients: experience from a UK tertiary centre. Clin Radiol 75:599–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2020.06.006

Hernigou J, Valcarenghi J, Safar A, Ferchichi MA, Chahidi E, Jennart H, Hernigou P (2020) Post-COVID-19 return to elective orthopaedic surgery-is rescheduling just a reboot process? Which timing for tests? Is chest CT scan still useful? Safety of the first hundred elective cases? How to explain the “new normality health organization” to patients? Int Orthop 44:1905–1913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04728-1

Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, Liu W et al (2020) Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 71:2027–2034. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa344

Watson J, Whiting PF, Brush JE (2020) Interpreting a covid-19 test result. BMJ 369:m1808. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1808

Mouton C, Hirschmann MT, Ollivier M, Seil R, Menetrey J (2020) COVID-19-ESSKA guidelines and recommendations for resuming elective surgery. J Exp Orthop 7:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-020-00248-4

Kort NP, Barrena EG, Bédard M et al (2020) Resuming elective hip and knee arthroplasty after the first phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: the European Hip Society and European Knee Associates recommendations. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:2730–2746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06233-9

Adamson PC, Goodman-Meza D, Vijayan T, Yang S, Garner OB (2020) Diagnostic yield of repeat testing for SARS-CoV-2: experience from a large health system in los Angeles. Int J Infect Dis 100:298–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.048

Yamamoto K, Saito S, Hayakawa K, Hashimoto M, Takasaki J, Ohmagari N (2020) When should clinicians repeat SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR?: Repeat PCR testing targeting patients with pulmonary CT findings suggestive of COVID-19.cript. Jpn J Infect Dis:1–19 Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.531

Kader N, Clement ND, Patel VR, Caplan N, Banaszkiewicz P, Kader D (2020) The theoretical mortality risk of an asymptomatic patient with a negative SARS-CoV-2 test developing COVID-19 following elective orthopaedic surgery. Bone Joint J 102-B:1256–1260. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.102b9.bjj-2020-1147.r1

Sutton D, Fuchs K, D’Alton M, Goffman D (2020) Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med 382:2163–2164. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2009316

Lin EE, Blumberg TJ, Adler AC, Fazal FZ, Talwar D, Ellingsen K, Shah AS (2020) Incidence of COVID-19 in pediatric surgical patients among 3 US Children’s hospitals. JAMA Surg 155:775–777. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2588

Keio university hospital (2020) Update on 2019 novel coronavirus situation at Keio University Hospital. Available at: http://www.hosp.keio.ac.jp/en/oshirase/detail/40174/. Accessed September 11, 2020

Doi A (2020) Cross-sectional study to estimate COVID-19 IgG positive rate in outpatients using anonymized preserved serum. Available at: http://www.kcho.jp/news/pressroom/ (in Japanese) Accessed September 11, 2020

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (2020) About coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020:1–1. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/newpage_00032.html. Accessed November 1, 2020

Blumberg TJ, Adler AC, Lin EE, Fazal FZ, Talwar D, Ellingsen K, Chandrakantan A, Chen J, Shah AS (2020) Universal screening for COVID-19 in children undergoing orthopaedic surgery: a multicenter report. J Pediatr Orthop 40:e990–e993. https://doi.org/10.1097/bpo.0000000000001657

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Drs Koji Goto, Hiromu Ito, Shunsuke Fujibayashi, Ryosuke Ikeguchi, Akio Sakamoto, Bungo Otsuki, Shinichi Kuriyama, Yutaka Kuroda, Shinichiro Nakamura, Ryuzo Arai, Koichi Murata, Toshiyuki Kawai, Takashi Noguchi, Takayoshi Shimizu and Yaichiro Okuzu for their valuable efforts in daily orthopaedic clinical services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM conceived and designed the study. KN collected and analysed data. KN, MN and SM drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a prospective case series under the approval of the ethics committee of Kyoto University Hospital (R2459). According to the ethical approval, informed consent to participate to this study was waived and opt-out was performed for all subjects in this study.

Consent for publication

According to the ethical approval, informed consent for publication of this study was waived and opt-out was performed for all subjects in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nishitani, K., Nagao, M. & Matsuda, S. Self-quarantine programme and pre-operative SARS-CoV-2 PCR screening for orthopaedic elective surgery: experience from Japan. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 45, 1147–1153 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-021-04997-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-021-04997-4