Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications for chest radiography and chest CT are among the most developed applications in radiology. More than 40 certified AI products are available for chest radiography or chest CT. These AI products cover a wide range of abnormalities, including pneumonia, pneumothorax and lung cancer. Most applications are aimed at detecting disease, complemented by products that characterize or quantify tissue. At present, none of the thoracic AI products is specifically designed for the pediatric population. However, some products developed to detect tuberculosis in adults are also applicable to children. Software is under development to detect early changes of cystic fibrosis on chest CT, which could be an interesting application for pediatric radiology. In this review, we give an overview of current AI products in thoracic radiology and cover recent literature about AI in chest radiography, with a focus on pediatric radiology. We also discuss possible pediatric applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chest radiography is one of the most commonly requested examinations in the workup of pediatric patients under suspicion of having a variety of diseases including pneumonia, tuberculosis and pneumothorax [1]. Chest radiographs are also commonly acquired to confirm the location of lines and tubes, or to surveil disease including oncologic disease. Chest CT is less commonly used in the pediatric population but can be helpful for assessing children with bronchial disease, infectious disease or interstitial lung disease.

Artificial intelligence (AI) software for chest imaging is being widely studied within radiology. To date this has resulted in more than 40 CE (Conformité Européenne)-marked commercial software packages from more than 20 vendors being available for clinical use in CT and conventional radiography of the thorax [2]. A wide range of abnormalities is covered by AI, in both chest radiography and chest CT. Most of the current AI products have been developed for the adult population, but they might be applicable to the pediatric population as well.

In this review, we discuss commercially available AI products for thoracic radiology. Because most of the current AI applications might not be specifically applicable to the pediatric population, we also discuss recent literature showing the potential for AI use in pediatric chest imaging. We emphasize the applications of AI in chest radiography rather than chest CT because radiography applications are of more interest in the pediatric population.

Current landscape of artificial intelligence products in thoracic radiology

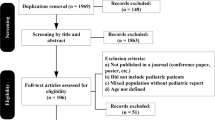

More than 40 AI applications are CE marked for thoracic radiology. This is the largest number of AI applications in radiology by subspecialty, after neuroradiology (Fig. 1) [2, 3]. Half of the products are developed for the analysis of chest radiography, and half for chest CT. No specific products have been developed and certified for the pediatric population (Table 1) [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, some products might be applicable to the pediatric population, as well. Current research per chest imaging modality is discussed next. In this review we emphasize the diagnostic applications, focusing on currently available commercial AI systems. Post-processing AI applications are not considered in this review.

Pie chart shows distribution by radiologic subspecialty of the 144 artificial intelligence (AI) products certified for image analysis in radiology at the time of this report [2]. MSK musculoskeletal, Neuro neurologic

Chest radiography

The first AI software products, or computer-aided detection software, for conventional chest radiography were designed to detect lung nodules with the goal to reduce missed lung cancers. These tools were then extended to detect other abnormalities on chest radiographs, such as pneumonia, pneumothorax and rib fractures (Fig. 2). A subset of applications is intended for triage, prereading images and flagging images on which urgent findings were detected by the AI system.

Bar chart shows artificial intelligence (AI) products available for chest radiographs at the time of this report [2]

Lung nodules

Automated lung nodule detection is the most studied application for chest radiography. Research that investigated the performance of lung nodule detection in chest radiographs started decades ago. With few publicly available datasets, systems were hard to compare. Steady improvement has been shown on the Japanese Society of Radiological Technology (JSRT) dataset consisting of chest radiographs with and without lung cancer, which can be used for validation purposes. First studies from 1999 reached a sensitivity of 35% at 6 false positives per image [30]; by 2014, this improved to a sensitivity of 75% at 0.5 false positives per image on this dataset [31]. Recently developed AI systems that incorporated deep learning have not tested their performances on the JSRT data but do report improved performances up to a sensitivity of about 80% at only 0.05 false positives per image [4].

For lung nodule detection, performance of these AI systems is similar or even surpasses the performance of radiologists. In a study from Nam et al. [4], a deep learning system that was trained on more than 40,000 chest radiographs showed in receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92–0.99 (depending on the validation set) for the detection of lung nodules with an average size ranging 20–40 mm. AI performance was similar or significantly better than that of the participating thoracic radiologists in this study. Most readers had improved performance when aided by the deep learning system.

Another recent study, by Yoo et al. [32], assessed the performance of their algorithm on chest radiographic screening data from the National Lung Screening Trial. On the baseline screening data, consisting of 5,485 radiographs, the algorithm reached a sensitivity of 94.1% and a specificity of 83.3% for detecting malignant pulmonary nodules.

Up to now, 11 certified products have been made available to help detect pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs. The developed systems have been trained on adult data, often older people with a high risk of lung cancer. However, the spectrum of abnormalities in the pediatric chest is different from that in adults. In the pediatric population, it would be more helpful to detect pulmonary metastases instead of potential lung cancers, which is relevant, for example, in children with osteosarcoma. However, such systems that aim to detect pulmonary metastases specifically are not yet available, and current systems trained on lung cancer data probably have a lower performance for the detection of pulmonary metastases. Furthermore, the pediatric chest is quite different from the adult chest with respect to shape, mediastinal contours and density of bone structures, which also might lower the performance of the current systems when applied to this population.

Tuberculosis and pneumonia

In the last few years, several studies have been published on the detection and diagnosis of consolidations in chest radiographs. Several groups have worked on AI to detect pulmonary tuberculosis in chest radiographs because resources and trained personal in developing countries are scarce, so automated evaluation of chest radiographs is especially beneficial in these countries. One of the first algorithms for tuberculosis, developed by Hogeweg et al. [33], showed a slightly lower performance than the observer for the detection of tuberculosis in a high-incidence population. Qin et al. [10] compared three available commercial deep learning systems and found similar performance of all systems for the detection of tuberculosis in chest radiographs, with an AUC ranging from 0.92 to 0.94 as compared with molecular testing. The AI systems reached higher specificity than the participating radiologists in the study, at a matched sensitivity level [10].

In addition to studies on AI for tuberculosis, studies are performed for AI that can help detect pneumonia [34,35,36]. In one of these studies [34], CheXNeXt, a convolutional neural network developed by the Stanford Machine Learning Group that can detect 14 pathologies on anteroposterior (AP) or posteroanterior (PA) chest radiographs, was tested on the chestX-ray8 dataset [37]. For 11 of the 14 pathologies, CheXNeXt achieved radiologist-level performance, including consolidations (AUC of 0.84 for radiologists versus 0.89 for the algorithm) [34]. In this study, radiologists achieved higher performance for the detection of emphysema, cardiomegaly and hiatus hernia [34].

Few studies have been performed in the pediatric population. The first study that was published examined AI to find any abnormality in pediatric chest radiographs in a very-high-incidence population suspected of tuberculosis (113/119 images) [38]. The system reached reasonable performance with an AUC of 0.78 for correctly identifying abnormal regions in the image [38].

A recent study reported results for CAD4Kids [39], which identified pneumonia in children younger than 5 years on chest radiographs. Sensitivity of the system was 76%, with a specificity of 80%. ROC performance was 0.85, which was significantly lower than that of a reference observer who reached an AUC of 0.98.

In the study by Tang et al. [40], the authors tested their algorithm for the detection of pneumonia on pediatric data and reached an AUC of 0.92, which was lower than the AUC of 0.98 on adult data. After retraining on pediatric data, the AUC improved to 0.98. And after fine-tuning, their algorithm improved further and reached an AUC of 0.99 for classifying normal images versus images with pneumonia [40].

Chen et al. [41] developed an algorithm for detecting common abnormalities in chest radiographs specifically for children ages 1–17 years. The reference standard in the study was set by a pediatric pulmonologist and radiologist in consensus. The algorithm reached an accuracy of 72% for detecting bronchopneumonia and 85% for detecting lobar pneumonia on a test set of 531 images [41]. The authors found greater disagreement in children younger than 5 years. This might be explained by a greater variance of chest shape in younger children.

Zucker et al. [42] explored the performance of an AI algorithm to determine the Brasfield score in children with cystic fibrosis. Their model, trained on roughly 1,800 children and tested on 200 children, achieved comparable performance with five participating radiologists for the most sub-features in scoring cystic fibrosis components in chest radiographs according to the Brasfield score [42].

Currently, seven certified AI products can detect pneumonia and five products can detect pulmonary tuberculosis. CAD4TB, a commercial AI system for the automated detection of tuberculosis, is the only certified product that can be used in children age 4 years and older [17].

Pneumothorax

Several studies have been performed for automatic pneumothorax detection in chest radiography, of which few have been developed into commercial software. Hwang et al. [6] reported excellent performance of their algorithm, with a median AUC of 0.97 (range 0.92–0.99), for the detection of pulmonary malignancies, tuberculosis, pneumonia and pneumothorax. Most radiologists improved in performance after using the algorithm.

Park et al. [43] tested a convolutional neural network to detect pneumothorax after transthoracic needle biopsy. Their network was trained on 1,596 chest radiographs and reached an AUC of 0.90 for the detecting pneumothorax 3 h after needle biopsy. As a reference standard, they used a consensus read of two experienced radiologists [43].

The study of Rajpurkar et al. [34] also evaluated pneumothorax detection. In this study their algorithm reached an AUC of 0.944, compared to an average AUC of 0.940 of radiologists. No statistical difference was found between the algorithm and the radiologists. Unfortunately, the algorithm was not tested on an external dataset.

Chen et al. [41], who developed a deep learning system for the most common abnormalities in pediatric chest radiographs, also tested their algorithm for the detection of pneumothorax and reached an accuracy 86%.

Currently, 11 commercially available packages offer pneumothorax detection. According to the reported literature, none of the certified products has been trained on pediatric data. Therefore, performance level of these AI products might be lower in the pediatric population.

Lines/tubes

Another possible worthwhile application is the detection of lines and tubes in chest radiographs. Malposition of lines disrupts proper treatment, and clear visualization of the line can help to avoid repeat radiographs and reduce patient radiation dose.

Several studies have been performed for the detection of lines and tubes in chest radiographs [44,45,46,47,48,49]. Generally the algorithms are quite good in classifying the presence versus absence of an endotracheal tube [50], but the systems perform worse when the exact position of the tip of the tube is sought.

Few studies for AI in the detection of lines and tubes have been performed in the pediatric population. In the study performed by Kao et al. [51], the authors developed an algorithm for detecting endotracheal tubes in neonatal chest radiographs. The authors evaluated the algorithm on 528 images with endotracheal tubes and 816 images without endotracheal tubes. The discriminant performance for detecting the existence of a tube reached an AUC of 0.94 [51]. The distance error of the tip of the tube was on average 1.89±2.01 mm [51].

In a study by Yi et al. [52], the authors used data with synthetic nasogastric tubes, endotracheal tubes and umbilical catheters to test their algorithm. The precision (i.e. true positives / [true positives + false positives]) for their algorithm was 0.80 [52]. According to the authors, their work can contribute to the development of a system that detects all lines and catheters in X-ray images and could be used to prioritize images that show malpositioned lines and request urgent review by the radiologist [52].

No commercial AI products are available that locate lines and tubes in chest radiographs. However, a single product on the market aims to optimize contrast for certain identification of lines and catheters (ClearRead Confirm; Riverain Technologies, Miamisburg, OH).

Chest computed tomography

Currently 21 CE-marked AI products for chest CT are available for use in daily clinical practice. Most applications focus on lung cancer detection and characterization. Other applications focus on the detection of pneumonia, especially in cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); the detection of obstructive lung disease; or the quantification of emphysema. Very few products are available for interstitial lung disease or the detection of pulmonary embolism (Fig. 3). Automatic detection of pulmonary embolism, quantification of emphysema, and detection and quantification of COVID-19 and fibrosis are less relevant for the pediatric population and therefore are not discussed here.

Bar chart shows artificial intelligence (AI) products available for chest CT at the time of this report [2]

Lung nodules

In CT, automatic lung nodule detection is the most widely studied application. The introduction of lung cancer screening has accelerated the quality and number of products for lung nodule detection in CT. Several studies have shown outstanding performance for the detection of lung nodules in CT [26, 28, 53, 54]; however, characterization of the nodules is a bigger issue. Many of the found nodules are small and benign. This has induced several approaches to characterize nodules and automatically estimate each nodule’s risk of malignancy [55, 56]. A recent study showed significantly improved performance of a convolutional neural network model for risk assessment of small nodules in CT compared with the Brock model, which is currently used for malignancy risk assessment, with an AUC of 0.90 compared with 0.87, respectively [55].

Eleven AI products are available for detecting pulmonary nodules in chest CT with the goal of finding early lung cancer. In the pediatric population, assessing pulmonary nodules in chest CT is not a clinical issue, and none of the products has been developed for the pediatric population. Nonetheless, these AI products might be useful for detecting pulmonary metastases, which is applicable in a specific pediatric population; none of products that is available, however, is specifically designed to detect pulmonary metastases.

Obstructive lung disease

Four products on the market focus on obstructive lung disease. These include chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma and cystic fibrosis. The latter two, especially, are applicable to children. Although CT examinations in asthma are not commonly performed, CT in cystic fibrosis patients is used to monitor the disease. AI software can detect minor attenuation differences in the lung, and thereby detect areas of air-trapping. Further, bronchopathic changes such as bronchial wall thickening and bronchiectasis can be detected and quantified. DeBoer et al. [57] showed that the number of airway counts on inspiratory high-resolution CT and the percentage of low-attenuation density on expiratory CT were significantly higher in children with cystic fibrosis.

A few products that can assess airway changes and air-trapping are available and should be usable in people with cystic fibrosis. However, no studies have been performed to assess the value of these products over visual assessment. Recently, Thirona B.V. (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) [58] obtained a patent for quantitative CT analysis of cystic fibrosis in children. They aim to develop an algorithm to identify early changes on CT scans in children with cystic fibrosis.

Pneumothorax

Several studies have examined the use of artificial intelligence in chest CT for the detection of pneumothorax. One example is the quick identification of pneumothoraces on chest CT [59]. This application reached a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 82.5%. The authors suggested that the tool could be used for triaging and to notify the radiologist about the detected urgent findings [59]. Complicating factors might be the presence of emphysema or bullae that could erroneously be seen as a pneumothorax. Other researchers tried to automatically quantify the volume of the pneumothorax. Rohrich et al. [60] showed excellent performance of their algorithm, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.996 between the automated quantification method and the manual measurement. For the pediatric population, one study investigated a computer-aided volumetry scheme for quantifying pneumothoraces in chest CT. The study performed by Cai et al. [61] also showed excellent performance, with Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.99 between the manual and automated measurements. This is important because a larger-volume pneumothorax might trigger different treatment. At this point, no commercial AI product is available for detecting and quantifying pneumothoraces in chest CT.

Future directions

Although AI applications for thoracic radiology are one of the most developed in radiology, still the use of these applications in clinical practice is scarce. But, with recent improvements in quality of the products and more attention on the clinical issues rather than technical possibilities, more products are expected to be implemented in the clinic in the near future. Unfortunately, this does not mean that the current AI products are of added value for the pediatric population. Literature with performance measures of AI products in thoracic radiology for the use in the pediatric population is limited, and very few of the current applications could be used in the pediatric population. To develop AI in pediatric chest radiology, more studies are needed to evaluate the performance of current available systems and also to develop AI products specifically aimed at the pediatric population.

One approach is to extend existing algorithms aimed at adults to the pediatric population. However, the intended use of current AI products in radiology is tailored to adults. If new studies of existing AI products were to show reliable performance in the pediatric population, the intended use of these products would be different and new certifications needed.

Furthermore, developers should focus on clinical issues in pediatric chest radiology. For instance, detection of pneumonia or pulmonary metastases in children could be helpful in clinical practice. Pneumonia in the pediatric population is common and can easily be diagnosed with chest radiography. Accurate detection of pulmonary metastases in chest CT of children with known malignancy might improve patient outcome. Apart from extending existing products, other difficult radiographic use cases could be addressed, for instance the automated grading of infant respiratory stress syndrome in premature newborns. Also, some products could be geared toward the non-pediatric radiologist, who might be less experienced in assessing pediatric imaging because of less exposure, for instance during on-call hours. One example of this could be automated detection of lines and tubes in newborns, an application that would also be helpful for clinicians.

Finally, AI could be used to improve imaging at acquisition and lower the radiation dose. With AI, CT dose could be lowered while preserving image quality in children [62, 63]. AI could also be used to reduce artifacts [64, 65]. This topic is outside the scope of this review because our focus is on diagnostic applications; however, continuing improvements in applications can be expected. CT imaging in children might therefore be less harmful with a lower radiation dose.

Conclusion

Multiple artificial intelligence products for chest radiology are available, covering a wide range of thoracic abnormalities. Reported performances of current products are promising, but little is known about their value in daily clinical practice. Products for pediatric chest radiology are scarce but might become more prevalent in the near future. The available studies and evidence discussed in this paper suggest that products for automated detection of pneumonia, tuberculosis and lines and tubes in chest radiography and cystic fibrosis in chest CT can be expected.

References

Hart A, Lee EY (2019) Pediatric chest disorders: practical imaging approach to diagnosis. In: Hodler J, Kubik-Huch RA, von Schulthess GK (eds) Diseases of the chest, breast, heart and vessels 2019–2022: diagnostic and interventional imaging. Springer, Cham, pp 107–125

Diagnostic Image Analysis Group (2020) AI for radiology: an implementation guide. https://grand-challenge.org/aiforradiology/. Accessed 8 Jun 2021

van Leeuwen KG, Schalekamp S, Rutten MJCM et al (2021) Artificial intelligence in radiology: 100 commercially available products and their scientific evidence. Eur Radiol 31:3797–3804

Nam JG, Park S, Hwang EJ et al (2019) Development and validation of deep learning-based automatic detection algorithm for malignant pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs. Radiology 290:218–228

Hwang EJ, Park S, Jin KN et al (2019) Development and validation of a deep learning-based automatic detection algorithm for active pulmonary tuberculosis on chest radiographs. Clin Infect Dis 69:739–747

Hwang EJ, Park S, Jin K-N et al (2019) Development and validation of a deep learning-based automated detection algorithm for major thoracic diseases on chest radiographs. JAMA Netw Open 2:e191095

Liang CH, Liu YC, Wu MT et al (2020) Identifying pulmonary nodules or masses on chest radiography using deep learning: external validation and strategies to improve clinical practice. Clin Radiol 75:38–45

Singh R, Kalra MK, Nitiwarangkul C et al (2018) Deep learning in chest radiography: detection of findings and presence of change. PLoS One 13:e0204155

Mushtaq J, Pennella R, Lavalle S et al (2021) Initial chest radiographs and artificial intelligence (AI) predict clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: analysis of 697 Italian patients. Eur Radiol 31:1770–1779

Qin ZZ, Sander MS, Rai B et al (2019) Using artificial intelligence to read chest radiographs for tuberculosis detection: a multi-site evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of three deep learning systems. Sci Rep 9:15000

Dellios N, Teichgraeber U, Chelaru R et al (2017) Computer-aided detection fidelity of pulmonary nodules in chest radiograph. J Clin Imaging Sci 7:8

Schalekamp S, Karssemeijer N, Cats AM et al (2016) The effect of supplementary bone-suppressed chest radiographs on the assessment of a variety of common pulmonary abnormalities: results of an observer study. J Thorac Imaging 31:119–125

Schalekamp S, van Ginneken B, Meiss L et al (2013) Bone suppressed images improve radiologists' detection performance for pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs. Eur J Radiol 82:2399–2405

Kligerman S, Cai L, White CS (2013) The effect of computer-aided detection on radiologist performance in the detection of lung cancers previously missed on a chest radiograph. J Thorac Imaging 28:244–252

Schalekamp S, van Ginneken B, Koedam E et al (2014) Computer-aided detection improves detection of pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs beyond the support by bone-suppressed images. Radiology 272:252–261

Sim Y, Chung MJ, Kotter E et al (2020) Deep convolutional neural network-based software improves radiologist detection of malignant lung nodules on chest radiographs. Radiology 294:199–209

Murphy K, Habib SS, Zaidi SMA et al (2020) Computer aided detection of tuberculosis on chest radiographs: an evaluation of the CAD4TB v6 system. Sci Rep 10:5492

Murphy K, Smits H, Knoops AJG et al (2020) COVID-19 on chest radiographs: a multireader evaluation of an artificial intelligence system. Radiology 296:E166–E172

Park S, Lee SM, Lee KH et al (2020) Deep learning-based detection system for multiclass lesions on chest radiographs: comparison with observer readings. Eur Radiol 30:1359–1368

Boes JL, Hoff BA, Bule M et al (2015) Parametric response mapping monitors temporal changes on lung CT scans in the subpopulations and intermediate outcome measures in COPD study (SPIROMICS). Acad Radiol 22:186–194

Labaki WW, Gu T, Murray S et al (2019) Voxel-wise longitudinal parametric response mapping analysis of chest computed tomography in smokers. Acad Radiol 26:217–223

Occhipinti M, Bosello S, Sisti LG et al (2019) Quantitative and semi-quantitative computed tomography analysis of interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis: a longitudinal evaluation of pulmonary parenchyma and vessels. PLoS One 14:e0213444

Romei C, Tavanti LM, Taliani A et al (2020) Automated computed tomography analysis in the assessment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis severity and progression. Eur J Radiol 124:108852

Jacobs C, van Rikxoort EM, Murphy K et al (2016) Computer-aided detection of pulmonary nodules: a comparative study using the public LIDC/IDRI database. Eur Radiol 26:2139–2147

Scholten ET, Jacobs C, van Ginneken B et al (2015) Detection and quantification of the solid component in pulmonary subsolid nodules by semiautomatic segmentation. Eur Radiol 25:488–496

Setio AAA, Traverso A, de Bel T et al (2017) Validation, comparison, and combination of algorithms for automatic detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography images: the LUNA16 challenge. Med Image Anal 42:1–13

Lo SB, Freedman MT, Gillis LB et al (2018) Journal club: computer-aided detection of lung nodules on CT with a computerized pulmonary vessel suppressed function. AJR Am J Roentgenol 210:480–488

Wagner A-K, Hapich A, Psychogios MN et al (2019) Computer-aided detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography using ClearReadCT. J Med Syst 43:58

Fischer AM, Varga-Szemes A, Martin SS et al (2020) Artificial intelligence-based fully automated per lobe segmentation and emphysema-quantification based on chest computed tomography compared with global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease severity of smokers. J Thor Imaging 35:S28–S34

Carreira MJ, Cabello D, Penedo MG, Mosquera A (1998) Computer-aided diagnoses: automatic detection of lung nodules. Med Phys 25:1998–2006

Schalekamp S, van Ginneken B, Karssemeijer N, Schaefer-Prokop CM (2014) Chest radiography: new technological developments and their applications. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 35:3–16

Yoo H, Kim KH, Singh R et al (2020) Validation of a deep learning algorithm for the detection of malignant pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2017135

Hogeweg L, Sanchez CI, Maduskar P et al (2015) Automatic detection of tuberculosis in chest radiographs using a combination of textural, focal, and shape abnormality analysis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 34:2429–2442

Rajpurkar P, Irvin J, Ball RL et al (2018) Deep learning for chest radiograph diagnosis: a retrospective comparison of the CheXNeXt algorithm to practicing radiologists. PLoS Med 15:e1002686

Yates EJ, Yates LC, Harvey H (2019) Re: machine learning "red dot": open-source, cloud, deep convolutional neural networks in chest radiograph binary normality classification. A reply. Clin Radiol 74:162–162

Behzadi-Khormouji H, Rostami H, Salehi S et al (2020) Deep learning, reusable and problem-based architectures for detection of consolidation on chest X-ray images. Comput Methods Prog Biomed 185:105162

Wang XS, Peng YF, Lu L et al (2017) ChestX-ray8: hospital-scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. Proc CVPR IEEE 2017:3462–3471

Mouton A, Pitcher RD, Douglas TS (2010) Computer-aided detection of pulmonary pathology in pediatric chest radiographs. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 13:619–625

Mahomed N, van Ginneken B, Philipsen RHHM et al (2020) Computer-aided diagnosis for World Health Organization-defined chest radiograph primary-endpoint pneumonia in children. Pediatr Radiol 50:482–491

Tang YX, Tang YB, Peng YF et al (2020) Automated abnormality classification of chest radiographs using deep convolutional neural networks. NPJ Digit Med 3:70

Chen K-C, Yu H-R, Chen W-S et al (2020) Diagnosis of common pulmonary diseases in children by X-ray images and deep learning. Sci Rep 10:17374

Zucker EJ, Barnes ZA, Lungren MP et al (2020) Deep learning to automate Brasfield chest radiographic scoring for cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 19:131–138

Park S, Lee SM, Kim N et al (2019) Application of deep learning-based computer-aided detection system: detecting pneumothorax on chest radiograph after biopsy. Eur Radiol 29:5341–5348

Sheng C, Li L, Pei W (2009) Automatic detection of supporting device positioning in intensive care unit radiography. Int J Med Robot 5:332–340

Ramakrishna B, Brown M, Goldin J et al (2012) An improved automatic computer aided tube detection and labeling system on chest radiographs. Proc SPIE 8315

Ramakrishna B, Brown M, Goldin J et al (2011) Catheter detection and classification on chest radiographs: an automated prototype computer-aided detection (CAD) system for radiologists. Proc SPIE 7963

Yu D, Zhang K, Huang L et al (2020) Detection of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in chest X-ray images: a multi-task deep learning model. Comput Methods Prog Biomed 197:105674

Lakhani P, Flanders A, Gorniak R (2021) Endotracheal tube position assessment on chest radiographs using deep learning. Radiol Artif Intell 3:e200026

Yi X, Adams SJ, Henderson RDE, Babyn P (2020) Computer-aided assessment of catheters and tubes on radiographs: how good is artificial intelligence for assessment? Radiol Artif Intell 2:e190082

Lakhani P (2017) Deep convolutional neural networks for endotracheal tube position and X-ray image classification: challenges and opportunities. J Digit Imaging 30:460–468

Kao EF, Jaw TS, Li CW et al (2015) Automated detection of endotracheal tubes in paediatric chest radiographs. Comput Methods Prog Biomed 118:1–10

Yi X, Adams S, Babyn P, Elnajmi A (2020) Automatic catheter and tube detection in pediatric X-ray images using a scale-recurrent network and synthetic data. J Digit Imaging 33:181–190

Zhao Y, de Bock GH, Vliegenthart R et al (2012) Performance of computer-aided detection of pulmonary nodules in low-dose CT: comparison with double reading by nodule volume. Eur Radiol 22:2076–2084

Silva M, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Jacobs C et al (2018) Detection of subsolid nodules in lung cancer screening: complementary sensitivity of visual reading and computer-aided diagnosis. Investig Radiol 53:441–449

Baldwin DR, Gustafson J, Pickup L et al (2020) External validation of a convolutional neural network artificial intelligence tool to predict malignancy in pulmonary nodules. Thorax 75:306–312

Tammemagi M, Ritchie AJ, Atkar-Khattra S et al (2019) Predicting malignancy risk of screen-detected lung nodules-mean diameter or volume. J Thorac Oncol 14:203–211

DeBoer EM, Swiercz W, Heltshe SL et al (2014) Automated CT scan scores of bronchiectasis and air trapping in cystic fibrosis. Chest 145:593–603

van Rikxoort EM, Charbonnier J-P, inventors; Thirona B.V., assignee. Computer implemented method for estimating lung perfusion from lung images. Dutch patent NL 2023710B1. 2021 Mar 4

Li X, Thrall JH, Digumarthy SR et al (2019) Deep learning-enabled system for rapid pneumothorax screening on chest CT. Eur J Radiol 120:108692

Rohrich S, Schlegl T, Bardach C et al (2020) Deep learning detection and quantification of pneumothorax in heterogeneous routine chest computed tomography. Eur Radiol Exp 4:26

Cai W, Lee EY, Vij A et al (2011) MDCT for computerized volumetry of pneumothoraces in pediatric patients. Acad Radiol 18:315–323

Akagi M, Nakamura Y, Higaki T et al (2019) Deep learning reconstruction improves image quality of abdominal ultra-high-resolution CT. Eur Radiol 29:6163–6171

MacDougall RD, Zhang Y, Callahan MJ et al (2019) Improving low-dose pediatric abdominal CT by using convolutional neural networks. Radiol Artif Intell 1:e180087

Alla Takam C, Samba O, Tchagna Kouanou A, Tchiotsop D (2020) Spark architecture for deep learning-based dose optimization in medical imaging. Inform Med Unlocked 19:100335

Xie SP, Zheng XY, Chen Y et al (2018) Artifact removal using improved GoogLeNet for sparse-view CT reconstruction. Sci Rep 8:6700

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schalekamp, S., Klein, W.M. & van Leeuwen, K.G. Current and emerging artificial intelligence applications in chest imaging: a pediatric perspective. Pediatr Radiol 52, 2120–2130 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-021-05146-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-021-05146-0