Abstract

The experience of diagnosis, decision-making and management in critical congenital heart disease is layered with complexity for both families and clinicians. We synthesise the current evidence regarding the family and healthcare provider experience of critical congenital heart disease diagnosis and management. A systematic integrative literature review was conducted by keyword search of online databases, MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycINFO, Cochrane, cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature (CINAHL Plus) and two journals, the Journal of Indigenous Research and Midwifery Journal from 1990. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to search results with citation mining of final included papers to ensure completeness. Two researchers assessed study quality combining three tools. A third researcher reviewed papers where no consensus was reached. Data was coded and analysed in four phases resulting in final refined themes to summarise the findings. Of 1817 unique papers, 22 met the inclusion criteria. The overall quality of the included studies was generally good, apart from three of fair quality. There is little information on the experience of the healthcare provider. Thematic analysis identified three themes relating to the family experience: (1) The diagnosis and treatment of a critical congenital heart disease child significantly impacts parental health and wellbeing. (2) The way that healthcare and information is provided influences parental response and adaptation, and (3) parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by how and when support occurs. The experience of diagnosis and management of a critical congenital heart disease child is stressful and life-changing for families. Further research is needed into the experience of minority and socially deprived families, and of the healthcare provider, to inform potential interventions at the healthcare provider and institutional levels to improve family experience and support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Antenatal care aims to provide positive pregnancy outcomes and experiences for women [1]. Antenatal ultrasound is a recommended aspect of care for screening of congenital abnormalities (inborn defects that affect a child’s physical structure or function) [1, 2]. Congenital anomalies are a significant cause of infant and child mortality and morbidity worldwide [2]. The most common fetal anomaly is congenital heart disease (CHD) [2]. Outcomes for CHD have improved with the modernisation of diagnostic and surgical methods [3]. Recent advancements have also improved the outcomes of the most severe CHD subgroup, Critical Congenital Heart Disease (CCHD). CCHD is a term for congenital cardiac diagnoses which require intervention in the neonatal period for survival [3, 4]. Infants within the CCHD group who function on a single ventricle, termed Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS), have the highest risk of mortality and are among the most medically complicated and controversial to manage [4, 5].

The parental experience of decision-making following a diagnosis of a fetal abnormality is complex and challenging [6,7,8,9]. Scholars and clinicians acknowledge that receiving an unexpected diagnosis of congenital heart disease is significant, usually resulting in parental grief and adaptation [8,9,10]. For more than fifty years, investigators have endeavoured to understand the nuclear (couple and dependent children) and wider extended family experience when parents receive a diagnosis of a congenital cardiac anomaly [11]. The continuum of intense stress from the time of life-threatening (often fatal) diagnosis onwards leads to anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, negatively affecting parenting practices and infant-parent bonding [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Despite increased knowledge about how mothers adapt following a fetal anomaly diagnosis, evidence about the whole (nuclear and wider) family experience of a life-threatening congenital cardiac diagnosis and treatment along the continuum of this distressing journey is not well understood [18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

The healthcare provider is integral to how the family experiences healthcare. Exploring healthcare provider experiences of diagnosing and managing CCHD infants could give insight into how values and perceptions may differ from patients during the decision-making process [25,26,27,28,29]. As the number of studies investigating the family experience of CCHD children increases, it would be expected that the physician stance and response increasingly would cater to the needs and lived experiences of families of CCHD infants. However, recent evidence suggests differing perspectives between parents and healthcare professionals caring for children with advanced heart disease in the hospital setting [30]. The gaps identified in patient-doctor communication related to key areas of cardiac disease status and, importantly, areas of prognosis [30]. Healthcare workers who care for infants with precarious survival may also feel emotionally burdened, with evidence supporting early input from palliative care facilitating coping for both family and provider [31].

Understanding provider and patient family experiences of the most life-threatening subset of the commonest fetal anomaly, CCHD, is, therefore, essential to inform best-practice healthcare delivery and facilitate coping. Thus, we aimed to synthesise current understanding about the family and healthcare provider experience of critical congenital heart disease diagnosis and management.

Methods

We used a systematic integrative review approach to synthesise current evidence exploring the families’ (nuclear and wider family) and healthcare workers’ experiences of CCHD diagnosis and management. Integrative review uses a systematic approach to incorporate studies with diverse methodologies to draw upon a wide range of evidence [32, 33]. The resultant thematic synthesis of information aims to comprehensively deepen the knowledge and understanding about a particular healthcare phenomenon [32, 33].

Search Strategy

The following search strategy used the online databases MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycINFO, Cochrane, cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature (CINAHL Plus) and two journals, the Journal of Indigenous Research and Midwifery Journal. These topic specific journals were searched to ensure a wide net was cast. Searches were carried out via title and keyword with search terms designed to capture variants of the review question with appropriate wildcards inserted to search for word truncations or variations in key terms (Table 1). Papers prior to 1990 were not searched to retain relevance to current systems and practice and ensure clinical applicability of search results.

Pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to screen for eligibility by title, abstract, and full text (Table 2). Screening and final cross-checking was carried out independently by SW and OI, with consensus on the final 22 included articles confirmed by KW following discussion where ambiguity existed. One first author was contacted to confirm inclusion criteria were met [34].

Data Extraction

Data extraction was completed using a pro forma, capturing relevant factors of the paper, study design and limitations [35]. Overall data relating to the family or provider experiences of CCHD diagnosis and treatment was noted.

Data Evaluation

Study quality was independently assessed by SW and OI incorporating three critical appraisal approaches: the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) [36]; the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [37] and a method developed by KW incorporating CASP with a quality framework suggested by Hawker and colleagues to systematically review studies from different paradigms [38]. Included papers were assessed by sections including methodological rigour, relevance to the research aim, appropriateness of the recruitment strategy, the standard of data collection and analysis, evidence of ethics and attention to potential biases such as whether there was reflexive analysis and study implications. The studies evaluated via these criteria were assessed by a categorical scoring system as good, fair, poor or very poor using a score out of 40. Quality was cross-checked between the two assessors and a consensus reached by a third assessor (KW) where ambiguity existed. The third assessor (KW) also cross checked 22% of the studies independently at random to ensure a rigorous and replicable assessment was reached.

Data Synthesis

The thematic data analysis occurred primarily by SW in four phases (Table 3) [39]. Data were extracted and tabulated in the form of base codes followed by identification of common themes. Tabulation allowed themes to be clearly grouped and then refined. Themes were refined with input from OI and KW and finalised by consensus between KW, OI and SW.

Results

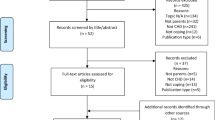

There were 1844 total studies identified during the initial electronic database search: 802 from Medline; 45 from PsycINFO; 685 from Cochrane, and 312 from CINAHL Plus. After exclusion of replicas, 1817 studies remained (Fig. 1).

The 22 included articles’ characteristics are summarised in Table 4. The majority of the 22 papers included in the review used qualitative methods. Three studies conducted focus group interviews [40,41,42], one study analysed journal entries [43], and the remainder conducted interviews. Two studies were mixed methods, including a quantitative arm with self-reported psychometric testing [44, 45]. One study triangulated their findings by assessing audio recordings of participant medical consultations [34]. Four studies had longitudinal data [42, 45,46,47], with two studies reporting on components of larger studies [42, 47]. Eighteen articles gathered cross-sectional information. Recruitment often occurred at large tertiary teaching hospitals and studies were conducted in Australia [44, 48], Canada [49, 50], Korea [51, 52], Norway [53], Sweden [54,55,56], Switzerland [57], the United Kingdom (UK) [34, 45, 58] and the United States of America (USA) [40,41,42,43, 46, 59, 60].

The overall quality of the included studies was generally good, apart from three of fair quality (Table 4) [34, 49, 53]. Participants were primarily English-speaking, married and well-educated. Studies lacked representation of minority ethnic groups, non-English speakers, single parents, and lower socioeconomic groups. Ten studies were retrospective narratives limited by possible recall bias. One study explored provider viewpoints on CCHD management, specifically in relation to the addition of mental health support services [60]. Twelve studies targeted CCHD alone, with a sub-group only assessing HLHS [44, 48, 49, 53, 58], the remaining ten included all CHD types. Common among studies was their focus on a discrete aspect of the experience (for example, the father’s experience or critical care experience).

Studies included in this review investigated the experience of diagnosis and/or management of CCHD for families and/or providers (data extraction summarised in Table 5). The healthcare provider perception was sought in one study, however, no insight was given into the provider experience, only the healthcare provider perception of the family experience. [60]

We found that experiencing an unexpected diagnosis of CCHD universally is devastating and shocking for families. Thematic analysis revealed three themes:

-

(1)

Experiencing the diagnosis and treatment of a CCHD child significantly impacts parental health and wellbeing.

-

(2)

Parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by how healthcare and information is communicated and provided, and

-

(3)

parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by how and when support occurs.

Theme 1 Experiencing the diagnosis and treatment of a CCHD child significantly impacts parental health and wellbeing

Families of children diagnosed with CCHD were significantly impacted in multiple spheres, including physical and mental health, family functioning and relationships [35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] There was also significant evidence of asynchronous responses between mothers and fathers, indicating that they respond differently to experiencing a diagnosis of CCHD and the process that follows [40, 41, 48, 51, 52, 59]. Intense emotional responses were universal between parents, including grief, shock, distress, depression, and anger [35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] Fathers were more likely to become angry than mothers [40]. Displaying characteristics of post-traumatic stress were common, with trauma resulting from diagnosis, seeing their children unwell (particularly in the unfamiliar intensive care setting) and unexpected events [44, 45, 48, 60]. Further stressors included the loss of their parenting role, painful time-pressured choices and feeling helpless from the loss of control [41, 44, 48, 58]. Loss of control was also of particular concern to fathers of CCHD infants [51, 52]. Mothers often felt guilty that their child’s CCHD was their fault, with the majority feeling the decisions regarding the management of the child’s condition (the choice of termination, continuation of pregnancy and active treatment or palliation) was ultimately their responsibility [43, 51, 58].

Fear was also a dominant feeling among parents of children with a CCHD diagnosis [40, 43, 47, 50, 51, 54, 57]. This fear became overwhelming at times, particularly of their child dying [45, 48]. There was also fear for the future and overall functioning of their child [40, 43]. This overwhelming fear was often coupled with uncertainty [34, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 49, 57]. Uncertainty was commonplace in experiencing the journey of having a CCHD infant—this uncertainty coupled with fear led to significant anxiety [40, 45]. This anxiety, in addition to the intense grief response, often led to parents describing physical impacts on their health such as exhaustion, feeling faint and tired. Compacting these physical sensations was the lack of self-care for their everyday physiological needs such as eating regularly and obtaining effective sleep [41, 42, 44, 45, 48].

Relationships were subsequently affected from experiencing a CCHD diagnosis, particularly within the nuclear family unit. There was evidence on the impact of the diagnosis on marriage/partnerships (positive and negative) from the strain of the experience and pressure from decision making [49, 57, 59]. Other siblings of the CCHD infant were also affected, with parents becoming less present but still having family commitments and demands, which needed to be balanced with the urgent demands of the CCHD child [48, 49, 51, 56]. Nuclear family functioning was also impacted by the demands of informing family and friends, with support for this greatly appreciated [57].

Theme 2 Parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by how healthcare and information is communicated and provided.

The healthcare provider team is central to parental experiences of the diagnosis and management of their CCHD infant [53]. The healthcare team's communication, interaction, and framing of medical information is critical to maintaining a trusting patient-provider relationship [44, 57, 60]. The relationship with the care team influences the family’s ability to cope and how they respond and experience the critical diagnosis of their child [44, 57, 60].

Clear and informative provider communication was paramount to the family experience [46, 54, 58]. Families often commented on the communication from the healthcare team, particularly the lead provider [41, 42, 44, 46, 54, 57,58,59,60]. Patient families appreciated timely information communicated in full and positioned impartially [46, 58]. The use of words without subjective negativity was valued, for example, ‘difference’ rather than ‘defect’ [51]. There appeared to be a lasting impact of negatively perceived or pessimistic counselling with families remembering words to describe their child’s diagnosis vividly many years after the fact [53, 58]. The information required by families needed to be matched to their needs to not be too overwhelming or uninformative, and vague [56]. The information was also appreciated when conveyed with respect, including respect for a parent’s religious/spiritual or belief system with empathetic non-verbal cues [54, 60]. When there was perceived disrespect or withholding of information, fragility in the patient-provider relationship occurred with distrust in individuals and the health system [57]. It was unclear whether initial distrust in the health system influenced this response.

Repeated discussions regarding the diagnosis and management of CCHD infants was important to parents [54]. This included drawn diagrams, written information (particularly in the native tongue) and recommended websites [34]. Families felt empowered to make more informed and confident decisions based on correct information from validated sources [34]. Further, clearly communicated logistics were helpful for families, such as what was required of them and how to balance other commitments [56]. For example, having open access to a specialised nurse was helpful during pregnancy after a prenatal diagnosis of CCHD occurred [56]. Consistency was also key to improved experiences. [42, 60] This included consistency of information delivered and the health care professionals providing the care [42, 60].

Additionally, the location in which information and care was delivered impacted the parental experience [42, 44]. The environment in the hospital setting (the ward and intensive care particularly) limited privacy and was overwhelming for families with unfamiliar medical equipment attached to their unwell infant [44]. Infant-parent bonding was also compromised due to the physical constraints of medicalisation [44]. Parents reported barriers in forming an intimate emotional bond with the CCHD infant secondary to their reduced parental role alongside reduced time and space to do so [40, 44, 48, 49, 57].

Theme 3 Parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by how and when support occurs

After the life-defining moment of diagnosis of their child with CCHD occurs, parents undertake a journey of adaptation [43,44,45,46,47, 50,51,52] How and when support occurs can shape how parents respond and adapt to their infant’s CCHD diagnosis [34, 46, 54, 60]. There are critical time-points when parental stress peaks and support needs appear to intensify [34, 46, 54, 60]. These time-points were identified as the time of diagnosis, decision-making (including deciding to terminate), birth or termination, at the point of surgery, entering intensive care post-surgery and discharge home [34, 46, 54, 60].

The way parents make sense of the CCHD diagnosis differs due to multiple factors such as underlying belief systems, available support networks and economic positioning [43, 46, 59]. Family functions also appear to impact adaptation responses as more dependants or those who live rurally appear to be more severely affected [44]. Therefore, practical supports such as economic (particularly for fathers and their work commitments), caregiving and informing and preparing for the expected and unexpected was appreciated [51, 56]. Particularly valued by families was support in the form of adequate information, compassion, thoughtfulness, and adequately managing uncertainty [34, 46, 55]. Further information on where to access peer support from individuals who had been in similar circumstances was also largely beneficial. Peers’ stories, often obtained from social media, the internet, and blogs, were valued by parents as they portrayed CCHD from another perspective than that of the healthcare system [56, 59, 60].

Discussion

This review has identified the available evidence on how the family of an infant with CCHD experiences the diagnosis and subsequent management (22 studies), and the provider experience of CCHD diagnosis and management (one study). [13, 61, 62] This one-sided narrative depicts a possible disconnect between what families are experiencing and what providers perceive in healthcare delivery. The repercussions of the current research not revealing both the provider and the family experiences is that how the healthcare providers and system is perceiving and responding to the family perspectives cannot currently be clearly understood.

This review has also highlighted that minority groups, immigrants and those in more deprived social circumstances are currently underrepresented in the available research, even though these groups experience racism, classism and resultant distress. [13, 61,62,63,64] The impact of this current unavailability of literature on the broad range of family experiences on critical congenital heart disease health care interactions is that important issues relating to these underrepresented groups remain concealed.

A recent literature review of 94 papers on families’ experiences of having a child with any CHD (not just critical types) supports the significant psychological effects expressed in this review, including stress, anxiety, and depression [65]. Intense grief reactions occur following the traumatic news of a life-limiting fetal anomaly regardless of the decision to continue the pregnancy or terminate [18]. Potential harm from a disconnect of beliefs and values between the provider and patient can occur [66]. Future improvements in care quality during a life-defining event may facilitate a less traumatic experience, further assisting parental adaptation and care engagement [67]. Parents with fewer resources for support psychosocially are more at risk of lower wellbeing over time [68]. Wider literature also supports our finding on gender differences in suffering experiences and subsequent coping methods, which is influenced by their role in family functioning, sociocultural expectations, and knowledge [69,70,71].

Care quality impacts the experiences of families with a CHD child, as found in one study included in this review [65]. Parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by the quality of healthcare information and the manner in which it is communicated and provided [72,73,74]. Early, honest, impartial communication is integral to establishing a trusting relationship [75, 76]. Differing levels of trust are associated with different patient preferences in decision making [77]. A complex shift in communication is required to ensure uncertainty in diagnosis and prognosis is discussed and managed appropriately [78, 79]. Intensive care is a particularly important and parental fear-inducing setting where communication preferences currently are not met adequately, particularly for minority families [80, 81].

Parental responses and adaptation can be influenced by how and when support occurs. Holistic support of families is required, including caring for the family’s financial needs. The cost of living with, or caring for, a child with CHD is high, with evidence of a high personal burden related to economic effects from high disruptions to daily living and high health care utilisation [82, 83]. A review of eight articles describing parental experiences with a child undergoing heart surgery reported a major theme as ‘balancing the parental role’ [84]. This is in keeping with our findings that supporting the parental role and family functioning is vital to how parents experience CCHD diagnosis and management. Family psychosocial coping varies over time making the timing of support crucial [85, 86]. Healthcare systems need targeted and timely interventions to accommodate this fluidity in family needs. Holistic, culturally appropriate support, including facilitating parent-infant bonding (particularly for Indigenous peoples), could be developed—particularly as it has been associated with reduced maternal anxiety and improved attachment in CCHD [87, 88].

Evidence about provider perspectives on caring for and managing CCHD is lacking. The sparse data drawn from this review included data from health care providers who manage HLHS but without a specific focus on their experiences [5, 89]. Although the goodwill of health care providers is clear to families, their insight is lacking in some areas [25, 28, 90, 91]. There is an accordance of opinions of health care providers and parents regarding a child’s perceived quality of life in CHD but further insight into why consultations can appear ad hoc is required [25, 28, 90, 91]. This review is limited by search terms covering the umbrella term CCHD; therefore, some available evidence may have been missed by not searching each individual diagnosis. Similarly, some non-English speaking participant groups may not be captured in this review by the use of the English language inclusion criteria.

Future Research Recommendations

An important focus for future inquiry is minority ethnic groups, non-English speaking, single parents, and low socioeconomic groups’ perspectives of CCHD diagnosis and management. Additional prospective longitudinal data on experiences of the pathway from prenatal diagnosis through to early childhood for parents with a CCHD child are needed. Integral to understanding this topic is understanding provider perspectives and experiences of CCHD care across the continuum (from diagnosis, counselling, and subsequent management). Broader research strategies could inform quality improvement so healthcare systems can function optimally, meet the needs of patients effectively and minimise potential harm. With future research aimed at understanding the full spectrum of family information and support needs, steps can be taken in maximising the effectiveness of interventions in these areas [92, 93]. Timely studies are also required due to the evolution of maternal–fetal surgery potentially contributing an added layer of management options for CCHD in the future [92, 93].

Conclusion

The experience of diagnosis and management of a CCHD child is stressful and life changing for families. Opportunities for interventions at the healthcare provider and institutional levels are available to enhance healthcare quality. Focusing future prospective, longitudinal research on diverse family and family experiences of CCHD could inform best-practice healthcare delivery and facilitate coping for all.

References

World health Organisation (2016) WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912

Lewanda A (2020) Birth Defects, Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development, pp 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.23682-1

Casey F (2016) Congenital Heart Disease. Congenital Heart Disease and Neurodevelopment, pp 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801640-4.00001-9

Sholler GF, Kasparian NA, Pye VE, Cole AD, Winlaw DS (2011) Fetal and post-natal diagnosis of major congenital heart disease: Implications for medical and psychological care in the current era. J Paediatr Child Health 47(10):717–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02039.x

Kon AA, Ackerson L, Lo B (2004) How pediatricians counsel parents when no ‘best-choice’ management exists. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 158(5):436. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.5.436

Ranjbar F, Oskouie F, Dizaji SH, Gharacheh M (2021) Experiences of Iranian women with prenatal diagnosis of fetal abnormalities: a qualitative study. Qual Rep 26(7):2282–2296. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4688

Araki N (2010) The experiences of pregnant women diagnosed with a fetal abnormality. J Japan Acad Midwifery 24(2):358–365. https://doi.org/10.3418/jjam.24.358

Lalor J, Begley CM, Galavan E (2009) Recasting Hope: a process of adaptation following fetal anomaly diagnosis. Soc Sci Med 68(3):462–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.069

Bijma HH, van der Heide A, Wildschut HIJ (2007) Decision-making after ultrasound diagnosis of fetal abnormality. Eur Clin Obstet Gynecol 3(2):89–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11296-007-0070-0

Jackson AC, Higgins RO, Frydenberg E, Liang RPT, Murphy BM (2018) Parent’s perspectives on how they cope with the impact on their family of a child with heart disease. J Pediatr Nurs 40:e9–e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.01.020

Glaser HH, Harrison GS, Lynn DB (1964) Emotional implications of congenital heart disease in children. Pediatrics 33:367–379. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.33.3.367

Vrijmoet-Wiersma CMJ, Ottenkamp J, van Roozendaal M, Grootenhuis MA, Koopman HM (2009) A multicentric study of disease-related stress, and perceived vulnerability, in parents of children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young 19(6):608–614. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951109991831

Franck LS, McQuillan A, Wray J, Grocott MPW, Goldman A (2010) Parent stress levels during children’s hospital recovery after congenital heart surgery. Pediatr Cardiol 31(7):961–968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-010-9726-5

Golfenshtein N (2016) Investigating parenting stress and neurodevelopment in infants with congenital heart defects during the first year of life. [Online]. Available: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=jlh&AN=123296044&site=ehost-live

Helfricht S, Latal B, Fischer JE, Tomaske M, Landolt MA (2008) Surgery-related posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: a prospective cohort study. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 9(2):217–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0b013e318166eec3

Aite L, Bevilacqua F, Zaccara A, la Sala E, Gentile S, Bagolan P (2016) Seeing their children in pain: symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of children with an anomaly requiring surgery at birth. Am J Perinatol 33(08):770–775. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1572543

Ec M (1998) Parental perception of stress during a child’s health crisis was represented by 4 dimensions. Evid Based Nurs 1(2):60–60

Wool C (2011) Systematic review of the literature: parental outcomes after diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Adv Neonatal Care 11(3):182–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0b013e31821bd92d

Soulvie MA, Desai PP, White CP, Sullivan BN (2012) Psychological distress experienced by parents of young children with congenital heart defects: a comprehensive review of literature. J Soc Serv Res 38(4):484–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2012.696410

Swanson LT (1995) Treatment options for hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a mother’s perspective. Crit Care Nurse 15(3):70–79

Bruce E, Lilja C, Sundin K (2014) Mothers’ lived experiences of support when living with young children with congenital heart defects. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 19(1):54–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12049

Re J, Dean S, Menahem S (2013) Infant cardiac surgery: mothers tell their story: a therapeutic experience. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 4(3):278–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150135113481480

Docherty SL, Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D (2002) Worry about child health in mothers of hospitalized medically fragile infants. Adv Neonatal Care 2(2):84–92. https://doi.org/10.1053/adnc.2002.32047

Dale MTG, Solberg O, Holmstrøm H, Landolt MA, Eskedal LT, Vollrath ME (2012) Mothers of infants with congenital heart defects: Well-being from pregnancy through the child’s first six months. Qual Life Res 21(1):115–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9920-9

Knowles RL, Griebsch I, Bull C, Brown J, Wren C, Dezateux C (2007) Quality of life and congenital heart defects: comparing parent and professional values. Arch Dis Child 92(5):388–393. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.075606

Hilton-Kamm D, Sklansky M, Chang R-K (2014) How not to tell parents about their child’s new diagnosis of congenital heart disease: an internet survey of 841 parents. Pediatr Cardiol 35(2):239–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-013-0765-6

Agosto C et al (2021) End-of-life care for children with complex congenital heart disease: parents’ and medical care givers’ perceptions. J Paediatr Child Health 57(5):696–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15316

Arya B, Glickstein JS, Levasseur SM, Williams IA (2013) Parents of children with congenital heart disease prefer more information than cardiologists provide. Congenit Heart Dis 8(1):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0803.2012.00706.x

Lotto R, Smith LK, Armstrong N (2017) Clinicians’ perspectives of parental decision-making following diagnosis of a severe congenital anomaly: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 7(5):e014716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014716

Morell E et al (2021) Parent and physician understanding of prognosis in hospitalized children with advanced heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 10(2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.018488

Afonso NS et al (2021) Redefining the relationship: palliative care in critical perinatal and neonatal cardiac patients. Children 8(7):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070548

Whittemore R, Knafl K (2005) The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 52(5):546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Cronin MA, George E (2020) The why and how of the integrative review. Organ Res Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120935507

Lotto R, Smith LK, Armstrong N (2018) Diagnosis of a severe congenital anomaly: a qualitative analysis of parental decision making and the implications for healthcare encounters. Health Expect 21(3):678–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12664

Ward K, Hoare KJ, Gott M (2014) What is known about the experiences of using CPAP for OSA from the users’ perspective? A systematic integrative literature review. Sleep Med Rev 18(4):357–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.01.001

Singh J (2013) Critical appraisal skills programme. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 4(1):76. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-500X.107697

Hong QN et al (2018) The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf 34(4):285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J (2002) Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 12(9):1284–1299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302238251

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Leuthner SR, Bolger M, Frommelt M, Nelson R (2003) The impact of abnormal fetal echocardiography on expectant parents’ experience of pregnancy: a pilot study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 24(2):121–129. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820309042809

Lisanti AJ, Golfenshtein N, Medoff-Cooper B (2017) The pediatric cardiac intensive care unit parental stress model: refinement using directed content analysis. Adv Nurs Sci 40(4):319–336. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000184

Hill C, Knafl KA, Docherty S, Santacroce SJ (2019) Parent perceptions of the impact of the Paediatric Intensive Care environment on delivery of family-centred care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 50:88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2018.07.007

Harvey KA, Kovalesky A, Woods RK, Loan LA (2013) Experiences of mothers of infants with congenital heart disease before, during, and after complex cardiac surgery. Heart Lung 42(6):399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.08.009

Cantwell-Bartl AM, Tibballs J (2013) Psychosocial experiences of parents of infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 14(9):869–875. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829b1a88

Gaskin KL, Barron D, Wray J (2021) Parents’ experiences of transition from hospital to home after their infant’s first-stage cardiac surgery: psychological, physical, physiological, and financial survival. J Cardiovasc Nurs 36(3):283–292. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000000727

Harris KW, Brelsford KM, Kavanaugh-McHugh A, Clayton EW (2020) Uncertainty of prenatally diagnosed congenital heart disease: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open 3(5):e204082. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4082

Clark SM, Miles MS (1999) Conflicting responses: the experiences of fathers of infants diagnosed with severe congenital heart disease. J Soc Pediatr Nurs 4(1):7–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.1999.tb00075.x

Cantwell-Bartl AM, Tibballs J (2014) Psychosocial responses of parents to their infant’s diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Cardiol Young 25(6):1065–1073. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951114001590

Ellinger MK, Rempel GR (2010) Parental decision making regarding treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care 10(6):316–322. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0b013e3181fc7c5d

Rempel GR, Ravindran V, Rogers LG, Magill-Evans J (2013) Parenting under pressure: a grounded theory of parenting young children with life-threatening congenital heart disease. J Adv Nurs 69(3):619–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06044.x

Kim J, Cha C (2017) Experience of fathers of neonates with congenital heart disease in South Korea. Heart Lung 46(6):439–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.08.008

Hwang J-H, Chae S-M (2020) Uncertainty of prenatally diagnosed congenital heart disease: a qualitative study. J Pediatr Nurs 53:e108–e113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.02.040

Vandvik IH, Førde R (2000) Ethical issues in parental decision-making. An interview study of mothers of children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Acta Paediatr, Int J Paediatr 89(9):1129–1133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb03363.x

Carlsson T, Bergman G, Wadensten B, Mattsson E (2016) Experiences of informational needs and received information following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defect. Prenat Diagn 36(6):515–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4815

Carlsson T, Marttala UM, Mattsson E, Ringnér A (2016) Experiences and preferences of care among Swedish immigrants following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defect in the fetus: a qualitative interview study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0912-1

Bratt EL, Järvholm S, Ekman-Joelsson BM, Mattson LÅ, Mellander M (2015) Parent’s experiences of counselling and their need for support following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease—a qualitative study in a Swedish context. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0610-4

Thomi M, Pfammatter JP, Spichiger E (2019) Parental emotional and hands-on work—Experiences of parents with a newborn undergoing congenital heart surgery: a qualitative study. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12269

Bertaud S, Lloyd DFA, Sharland G, Razavi R, Bluebond-Langner M (2020) The impact of prenatal counselling on mothers of surviving children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a qualitative interview study. Health Expect 23(5):1224–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13103

Sood E et al (2018) Mothers and fathers experience stress of congenital heart disease differently: recommendations for pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 19(7):626–634. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001528

Woolf-King SE, Arnold E, Weiss S, Teitel D (2018) ‘There’s no acknowledgement of what this does to people’: a qualitative exploration of mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects. J Clin Nurs 27(13–14):2785–2794. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14275

Small R et al (2014) Immigrant and non-immigrant women’s experiences of maternity care: a systematic and comparative review of studies in five countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-152

Perez Jolles M, Richmond J, Thomas KC (2019) Minority patient preferences, barriers, and facilitators for shared decision-making with health care providers in the USA: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 102(7):1251–1262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.003

Paradies Y et al (2015) Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10(9):1–48. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

Mahabir DF, O’Campo P, Lofters A, Shankardass K, Salmon C, Muntaner C (2021) Classism and everyday racism as experienced by racialized health care users: a concept mapping study. Int J Health Serv 51(3):350–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207314211014782

Wei H, Roscigno CI, Hanson CC, Swanson KM (2015) Families of children with congenital heart disease: a literature review. Heart Lung 44(6):494–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.08.005

Fernandes JRH (2005) The experience of a broken heart. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 17(4):319–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2005.08.001

Wilpers A et al (2021) The parental journey of fetal care: a systematic review and meta synthesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 3(3):100320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100320

Jackson AC, Frydenberg E, Liang RPT, Higgins RO, Murphy BM (2015) Familial impact and coping with child heart disease: a systematic review. Pediatr Cardiol 36(4):695–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-015-1121-9

Kim S, Im YM, Yun TJ, Yoo IY, Kim S, Jin J (2018) The pregnancy experience of Korean mothers with a prenatal fetal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2117-2

Lin PJ, Liu YT, Huang CH, Huang SH, Chen CW (2021) Caring perceptions and experiences of fathers of children with congenital heart disease: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Int J Nurs Pract 27(5):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12952

Doherty N et al (2009) Predictors of psychological functioning in mothers and fathers of infants born with severe congenital heart disease. J Reprod Infant Psychol 27(4):390–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903190920

Wei H, Roscigno CI, Swanson KM (2017) Healthcare providers’ caring: nothing is too small for parents and children hospitalized for heart surgery. Heart Lung 46(3):166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.01.007

Kratovil AL, Julion WA (2017) Health-care provider communication with expectant parents during a prenatal diagnosis: an integrative review. J Perinatol 37(1):2–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.123

Garwick A, Patterson J, Bennett F, Blum R (1995) Breaking the news. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 149:991–997. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.8.40.18.s43

Carlsson T, Bergman G, Marttala UM, Wadensten B, Mattsson E (2015) Information following a diagnosis of congenital heart defect: experiences among parents to prenatally diagnosed children. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117995

Rentmeester CA (2001) Value neutrality in genetic counseling: an unattained ideal. Med Health Care Philos 4(1):47–51. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009972728031

Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB (2004) How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision-making? Health Expect 7(4):317–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00296.x

Kuang K (2018) Reconceptualizing uncertainty in illness: commonalities, variations, and the multidimensional nature of uncertainty. Ann Int Commun Assoc 42(3):181–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1492354

Stewart JL, Mishel MH (2000) Uncertainty in childhood illness: a synthesis of the parent and child literature. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 14(4):573–574

Lisanti AJ, Allen LR, Kelly L, Lisanti Medoff-Cooper Amy Jo BAI-O (2017) Maternal stress and anxiety in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 26(2):118–125. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2017266

Zurca AD, Wang J, Cheng YI, Dizon ZB, October TW (2020) Racial minority families’ preferences for communication in pediatric intensive care often overlooked. J Natl Med Assoc 112(1):74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.09.005

Connor JA, Kline NE, Mott S, Harris SK, Jenkins KJ (2010) The meaning of cost for families of children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Health Care 24(5):318–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.09.002

Strange G et al (2020) Living with, and caring for, congenital heart disease in Australia: insights from the congenital heart alliance of Australia and New Zealand online survey. Heart Lung Circ 29(2):216–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2018.12.009

de Man MACP et al (2021) Parental experiences of their infant’s hospital admission undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Acta Paediatr, Int J Paediatr 110(6):1730–1740. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15694

Lumsden MR, Smith DM, Wittkowski A (2019) Coping in parents of children with congenital heart disease: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Child Fam Stud 28(7):1736–1753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01406-8

Golfenshtein N, Hanlon AL, Deatrick JA, Medoff-Cooper B (2019) Parenting stress trajectories during infancy in infants with congenital heart disease: comparison of single-ventricle and biventricular heart physiology. Congenit Heart Dis 14(6):1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/chd.12858

Adcock A, Cram F, Edmonds L, Lawton B (2021) He tamariki kokoti tau: families of indigenous infants talk about their experiences of preterm birth and neonatal intensive care. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(18):9835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189835

Lisanti AJ et al (2021) Skin-to-skin care is associated with reduced stress, anxiety, and salivary cortisol and improved attachment for mothers of infants with critical congenital heart disease. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 50(1):40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2020.09.154

Prsa M, Holly CD, Carnevale FA, Justino H, Rohlicek Cv (2010) Attitudes and practices of cardiologists and surgeons who manage HLHS. Pediatrics 125(3):e625–e630. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1678

Daily J et al (2014) Important knowledge for parents of children with heart disease: parent, nurse, and physician views. Cardiol Young 26(1):61–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951114002625

Weeks A, Saya S, Hodgson J (2020) Continuing a pregnancy after diagnosis of a lethal fetal abnormality: views and perspectives of Australian health professionals and parents. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 60(5):746–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13157

Carlsson T, Marttala UM, Wadensten B, Bergman G, Mattsson E (2016) Involvement of persons with lived experience of a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defect: an explorative study to gain insights into perspectives on future research. Res Involv Engagem 2(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-016-0048-5

Antiel RM (2016) Ethical challenges in the new world of maternal-fetal surgery. Semin Perinatol 40(4):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2015.12.012

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Dr Simone Watkins was financially supported by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Pacific Career Development Award 21-203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW wrote the main manuscript text with supervision from primarily KW and also oversight from FB and TG. OI assisted with data collection and collaboration. Analysis was completed primarily by SW with input from KW. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Watkins, S., Isichei, O., Gentles, T.L. et al. What is Known About Critical Congenital Heart Disease Diagnosis and Management Experiences from the Perspectives of Family and Healthcare Providers? A Systematic Integrative Literature Review. Pediatr Cardiol 44, 280–296 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-03006-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-03006-8