Abstract

Objectives

Congenital heart defects (CHD) can be detected at ultrasound but are sometimes not diagnosed until birth, which can cause stress and heightened emotion within the family. Parents face challenges including dealing with surgical procedures for their child and integrating healthcare management into family life. The aim of this review was to understand parental coping with their child’s CHD.

Methods

Six databases were systematically searched to identify qualitative studies relating to parental coping in the context of having a child with CHD and which met inclusion criteria. Studies were subject to quality appraisal using Walsh and Downe’s checklist, and synthesised using Noblit and Hare’s meta-ethnographic approach.

Results

The synthesis of 22 studies reporting on 704 parents’ accounts showed that parent coping fell within four overarching themes: Emotional Responses, Support Systems, Parental Management and Avoidance. These four themes contained 13 subordinate themes.

Conclusions

Parental psychosocial coping varies over time from diagnosis, through surgery to childhood. Common themes were evident, but individuals employed their own styles and strategies based on prior experience, availability of social support, personal characteristics and beliefs. Parents tried to maintain a sense of normality, integrating CHD into their lives without it having a major impact except at times of transition and hospitalisation when they had to call on additional strategies or support to manage this stress. This review offers clear guidance to clinical services on how best to support parents and families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) is one of the most common types of birth defects, affecting 8 per 1000 babies born globally (Bernier et al. 2010), and prevalence has increased over time (van der Linde et al. 2011). As there are many variations of CHD which sometimes occur in combination and with differing severities, prognosis and treatment may vary between individuals. NICE guidance (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016) advises that “children, young people and their parents or carers may need support, and sometimes expert psychological intervention, to help with distress, coping, and building resilience” (p. 14) and emotional and psychological wellbeing should be discussed with families regularly, particularly at times of transition. Chronic illnesses, such as CHD, and their associated complications can adversely impact family life (Alkan et al. 2017; Tak and McCubbin 2002; Werner et al. 2014; Wray and Maynard 2005). Presence of CHD has been shown to increase the vulnerability of the whole family to psychological and social distress (Doherty and Utens 2016; Mussatto 2006; Soulvie et al. 2012). However, using the perspective of coping, many studies also show that parents and families manage to adjust to the presence and demands of childhood conditions (Bajracharya and Shrestha 2016; Spijkerboer et al. 2007). For example, families can be put under strain of a chronic illness at various time points (Sawyer and Spurrier 1996) including at diagnosis (Ailes et al. 2014), birth (Brosig et al. 2007), surgery (Utens et al. 2000) and adapting to the integration of healthcare alongside typical parenting (Goldberg et al. 1990; Lawoko and Soares 2002).

The experiences of parenting a child with a chronic illness, and the impact of paediatric illness on families, have been reviewed (Cousino and Hazen 2013; Shudy et al. 2006). In their review of 94 studies to explore the impact of CHD on families, Wei et al. (2015) identified major themes based on quantitative checklists of parents’ psychological health, family life, parenting challenges and family-focussed interventions. However, most of these studies were quantitative and used self-report measures with pre-defined questions and answers. As such, these studies could not have reported on the detailed influences of CHD on parents and certainly not in the parents’ own words. Furthermore, deductive methods use prior assumptions that may not answer the research question (Al-Busaidi 2008). In contrast to quantitative methods, qualitative methods provide details about human behaviour, emotion and personality characteristics and they enable researchers to make sense of patterns in the meaning through differences and divergence, particularly in health research (Pope and Mays 1995).

In another review of 25 studies, featuring mostly quantitative designs but also including some qualitative papers, Jackson et al. (2015) identified that the impacts on a family can include psychological distress and wellbeing, family functioning and quality of life. Coping styles varied dependent on age and gender; mothers sought social support, “vented” about their situation and turned to spirituality or religion, whereas fathers were more likely to use alcohol as a coping mechanism.

Coping is a broad term, and so various definitions were considered (Lazarus and Folkman 1987; Snyder 2014) including those specific to psychological adjustment to chronic illness (Felton et al. 1984; Moss and Billings 1982) which had been used in other studies on parental coping (Grootenhuis and Last 1997b; Seideman et al. 1997). These definitions shared similarities relating to the problem-focus or emotion-focus of distress, and the subsequent responses intended to reduce the burden of stressful life events. The Snyder (2014) definition of coping refers to any strategies that effectively manage emotional, physical or psychological burdens, and was considered sufficient and appropriate to cover the breadth of literature exploring parental coping.

We set out to answer the following research question: How do expectant parents and parents of children with CHD cope with their experience from diagnosis, surgery and beyond?

Method

The meta-ethnographic approach described by Noblit and Hare (1988), was selected to synthesise the findings from the included studies. It is a commonly used idealist technique to synthesise and explore differences between studies (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009), whilst preserving the rigour and quality of the primary data (Sin 2010).

The main themes and concepts identified from systematic searches of the qualitative literature were synthesised to establish broader themes across the studies to be included in this review. The seven-step-approach (Noblit and Hare 1988) was chosen to guide the synthesis process which consists of: 1) Research question, 2) systematic review process, 3) reading and rereading studies and the identification of primary and secondary themes, 4) determine how studies are related to each other, 5) translate the studies into one another, 6) synthesise translations and 7) express the synthesis. A systematic search of six databases was conducted in October 2017 (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed, ProQuest and Web of Science). Online databases were systematically searched by the first author (MRL). Keywords from four broad areas relating to CHD, coping, family and child were truncated. Multiple synonyms of search terms were utilised using Boolean search operators AND/OR across all databases, with exploded or Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms, when available. Broad search terms were selected to cover a wide range of papers based on the SPIDER search tool (Cooke et al. 2012). Hand searching was also undertaken. First, the reference lists of identified papers were scrutinised for additional papers. Secondly, Google Scholar was searched for additional studies using simple broad-based terms to identify any remaining studies (Flemming and Briggs 2007).

Studies were included in the review based on the following eligibility criteria: 1) an empirical study collecting qualitative data published in peer reviewed journals, 2) reporting on experiences of parents of infants and children diagnosed with congenital heart disease including how they coped at various stages, 3) included studies utilised samples of parents, over 18 years of age, who had a child who had been diagnosed with a congenital heart defect (CHD). The Snyder (2014) definition of coping was used in our selection of studies so that any paper which made reference to parents managing an emotional, physical or psychological burden was included. No restriction was placed on language or year of publication. Studies deemed as very poor quality were excluded from the review.

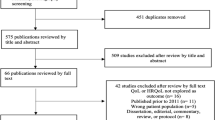

The search process is illustrated in Fig. 1. The researchers adhered to PRISMA guidelines (Liberati et al. 2009) for systematic reviews and metasyntheses and registered the review on PROSPERO (CRD42017049683) prior to searching (Booth et al. 2012). The first author screened the search results against the identified eligibility criteria. An independent researcher screened 10% of the search results to provide a measure of reliability of the screening process. The agreement between researchers was 100%.

The Walsh and Downe (2006) quality appraisal checklist was used to assess 12 different aspects of methodological and interpretive rigour in the included qualitative studies. This checklist contains 12 criteria covering eight stages of research from scope and purpose to relevance and implication of findings. Studies were rated against each of the 12 items and awarded a point if they met criteria fully. The following categories were used: Category A represented studies which were rated as high quality and low methodological bias; these studies scored between 9 and 12. Category B studies were rated as moderate quality; these studies scored between 6 and 8. Category C studies scored below 6 (less than half of the maximum score) and were considered to represent low quality and high methodological bias; therefore, they were excluded from this meta-synthesis (Hannes 2011). The methodological quality of the identified studies was appraised by the first author (MRL). Thirty per cent of papers were reviewed by an independent researcher (K.C.) to verify the accuracy of the quality assessment.

Results

The literature search yielded 22 studies that reported on parental coping with a child diagnosed with a CHD, or a prenatal diagnosis (Table 1). The characteristics for these studies can be seen in Table 2. Studies were from the USA (n = 10), Canada (n = 6), Australia (n = 2), UK (n = 1), Japan (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1) and Taiwan (n = 1). The methods of analysis used in the studies included content analysis (n = 7), grounded theory (n = 5), phenomenological analysis (n = 3), thematic analysis (n = 3) and framework analysis (n = 1). Three studies used secondary analysis and did not detail a specific methodology. Most studies used purposive or convenience samples from health centres and hospitals associated with the researchers. The majority of studies used interviews to collect data, with three reusing data sets through secondary analysis of existing interview transcripts and memos. Two studies used focus groups, while one examined journal entries and one asked open-ended questions as part of a survey. The median sample size was 16, ranging from 8 to 175 participants.

The studies represented data from 704 parents (511 mothers, 176 fathers, 17 unreported), aged between 18 and 60 years, of children pre-birth to 19 years old. Ethnicity and socioeconomic status varied within and between studies. Some studies focused only on the experience of pregnancy, while others explored parental coping throughout their child’s life. Details of the final 22 studies are summarised in Table 2.

All of the eligible studies were screened against Walsh and Downe’s (2006) criteria. Table 3 provides an overview of scores for each included study. Eight of the studies included in this meta-synthesis were rated as category A and 15 were rated as category B. The rating and categorisation process of 30% of the initial 27 studies was also checked by an independent researcher for reliability. There was 75% agreement in the categorisation of the ratings.

Synthesis

Despite differences between the studies’ aims, methodology and analysis, there were similarities in the findings, suggesting a shared sense of reported parent coping with a child with a diagnosis of CHD. Four overarching themes emerged from the synthesis, which contained 13 sub-ordinate themes. Figure 2 illustrates the structure of themes and sub-themes.

Emotional Responses

Most of the studies detailed parents’ emotional responses as part of their coping, at the initial discovery of their child’s diagnosis as well as during the surgeries. This theme comprised of three further subthemes that expanded on the category.

Expressing or Withholding Emotion

This theme describes the expression of emotion in relation to their child, but also considers parents’ use of suppression or denial in order to protect themselves from overwhelming emotions, such as shock, grief, guilt, hopelessness, anxiety, anger, sadness and fear: “To define in words the emotion, questions, uncertainty, emptiness, and broken heart that I carried with me through the situation is impossible”(Harvey et al. 2013). Participants in 11 out of 22 studies talked about experiencing extremes of emotion and expressing these: “When my son was in surgery, I cried uncontrollably. I wanted someone to be with me, give me a little hand-holding, and tell me he’s going to be ok.” (Wei et al. 2017), showing how the expression of emotion functioned to communicate to others the need for support. One parent described the strong anger they felt after hearing the diagnosis which has prevailed throughout their child’s life: “I had a lot of anger at God. I was furious and I still am” (Leuthner et al. 2003).

In contrast, and only reported in a few studies, some parents described suppressing their emotions in order to cope with their everyday lives: “I am very emotional but I cannot keep walking around with sad face, be depressed. If I get sick who is going to take care of my kids?” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017).

Attachment or Detachment

This theme captured how parents bonded with their child both before s/he was born and just after birth, prior to their first surgery. These were precarious periods when parents did not know the extent of their child’s complications, nor whether they would survive through a complex operation at such a young age.

Parents who treated the foetus as a child before they were even born felt as though s/he was more real, and they were able to form loving attachments even in the face of possible loss: “It’s your kid [child]. You’re the parent of that kid [in utero] that has the birth defect. And it’s just such a hard thing to just do, day by day and everything. This is why I’m feeling this way, because I am the parent” (McKechnie et al. 2015). “It’s my baby and I love him immensely. I loved him before he was born and I loved him when he was born” (McKechnie and Pridham 2012).

Other parents did not form the same attachments and reported feeling detached from their child before they were born because they did not know if they would survive: “We didn’t know if she would make it through the first surgery or anything…. not to say you’re detached but you’re a bit guarded… I loved her and I knew that we wanted to keep her but you don’t connect” (Rempel et al. 2013). During the surgery when there was a real risk of losing their child, parents’ fear of forming attachments made them avoid getting too close: “I guess in the back of my mind, I felt that, if she was going to die, then probably the sooner the better because I just knew with time we’d get more and more attached to her” (Rempel et al. 2012) and some did not want to even think about growing close to their child until they knew it would survive: “take him away, make him better and then I… may be able to bond” (Leuthner et al. 2003).

Positive Thinking

This theme explored how parents coped with the often honest or blunt prognosis of their child’s condition. Cardiologists typically informed them of the odds that were not necessarily in their favour, and parents were given the decision of whether to terminate or proceed with pregnancy, then give their child either palliative care or the process of open heart surgery. Parents coped with these dilemmas by believing their child was on the other side of the odds, hoping that they were not part of the risk statistic and doctors were wrong with their prognosis: “Hope! Yeah, that’s all we had, really. I think that throughout the whole thing, the only hope that we ever had was basically that they [diagnosing physicians] were wrong. You can only be so precise when you’re looking through mom, through baby, into a heart. What we heard from the beginning, though, was, ‘Know we can be wrong.’ This is the one case I do not mind doctors being wrong at all. So that was the basis of hope right there” (McKechnie and Pridham 2012). When faced with the reality of parenting a child with long term complex health needs, parents still held onto their optimism: “That’s when I was like, ‘We can do this. We’re going to do this. We’re going to bring him home. He’s going to do anything he wants in life, and he’s going to outlive us.’ And I’m going to make everything in my body, anything in my will power to make that happen” (McKechnie et al. 2015).

Positive thinking varied at different stages of parenting, and the initial shock of the CHD diagnosis led some parents to lose that hope. Despite awareness of children who had gone through the process successfully, some parents struggled to accept the possibility of a negative outcome in case it did not apply to them: “It is hard sometime to stay positive when the specialist is not positive. I had to tell my mom- I cannot hear these success stories anymore because it might not happen for us. So on some days it’s helpful for me, but on others… it’s back and forth” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017). However, once the child had made it through the surgical procedures, parents reported embracing the positivity in the unknown: “So you learn to take one day at a time with her and enjoy all the little quirks that she does” (Rempel et al. 2012).

Support Systems

A main form of coping for parents emerged in the theme of support systems; it was present in some form in 19 of the 22 studies. Parents cited various people they called upon at different stages of their journey to seek support, whether this was emotional, practical, reassuring or information providing. While most parents accessed some form of support, they still acknowledged that other people did not truly understand what they were experiencing unless they had gone through a similar experience themselves: “Seek out other parents who have gone through it, and talk with them. Nobody that hasn’t gone through it will understand what you are going through” (Sira et al. 2014).

Support Within the Couple

Parents reported turning to someone close to them for emotional and practical support. Most of the participants in the studies were married or cohabiting, so often shared their experience with their partner who was able to appreciate first hand their distress and provide support. Support from the partner was present in seven of the studies: “The one person who could <understand> was my husband. He is my best friend, plus the father of my child” (Harvey et al. 2013). “So, my husband is my greatest spiritual support. Yes…spiritual support. If there weren’t him, I couldn’t have got through it” (Lan et al. 2007). Some parents recognised the importance of a shared attitude towards their child, and that it could be difficult to support each other if this was absent, “If you both agree that you want to keep the baby and you know, if you have the same goals in general, I don’t think it’s that hard on the relationship” (Rempel et al. 2012).

Support from Peers and Family

For many parents, close family, particularly their child’s grandparents, became an invaluable source of support to help parents cope. This consisted of emotional support: “Me and my father have never been close before, but now he gives me all this support, he told me that he is proud of me. For him to actually say this made me feel really better” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017). But it also consisted of practical support to parents whenever they needed it: “…even just going to the grocery store, or washing my little boy, or not asking me what I need, but just looking around the house to see we need laundry to be done. That’s one thing that my mom is good at- she does what needs to be done without asking a hundred times. I don’t want to tell you, just notice and do it!” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017).

Many parents made connections with others in similar situations through support forums, and described how they gradually became friends through a shared understanding: “We joined the Association for Children’s Hearts to look for like-minded people… it’s not so often you run into a family with children with heart defects… but through this association we gained a great deal. It felt like it was, yes, the ability to be able to keep the head clear in some way” (Bruce et al. 2014). “The ‘what ifs’ were the big thing. But once I talked to [friend] and learned and listened to her calmness and her organization of things—how to prepare, how to function at home —just listening to what she had to go through, prepared me. So, just asking all the questions and the “what ifs” just calmed me and helped me deal with it” (Rempel et al. 2009). For some parents, the anonymity and availability of online support groups helped them to cope in a way that suited them: “I do not utilize in-person groups… however, I love my online family!” (Sira et al. 2014).

Support from Professionals

Professionals held the position of expert at the start of parents’ journeys, and so were the first providers of information and advice. Parents reported that the honesty, reassurance and information that professionals provided helped them to understand their child’s condition more, and in turn cope better with what they faced as a family: “Every day we started to cope a bit better because we got enough information from the doctor” (Cantwell-Bartl and Tibballs 2013). “We were very upset initially till we saw the cardiologist. Everyone there was positive about the whole thing. Because of them, we had a great pregnancy” (Wei et al. 2017).

However, some parents did not feel that professionals helped them to cope, because they felt unsupported by medical staff: “We didn’t have the time or the knowledge to ask everything we wanted to. We were still kind of blown away and it was just information overload on top of it… We got a hand drawn heart on a napkin with everything that was wrong… it’s like, “Really? You couldn’t have gotten a model of the heart to explain everything to us?” (McKechnie et al. 2016). Some professionals seemed to strike the wrong chord with parents, offering unsolicited sympathy: “I found myself, even within just a few weeks [of the diagnosis], getting mad at people.…A genetic counsellor wanted to give me a big hug and [said], ‘I’m so sorry.’ And I’m already kind of getting defensive and getting mad because I’m like, ‘She’s still a baby, and we’re still happy to have her.’ It made me feel like I’m already a parent of a kid with special needs. And I’m not apologizing for my kids, so don’t pity me, don’t pity my kid” (McKechnie et al. 2015).

Support Through Faith and Spirituality

This sub-ordinate theme featured in almost half of the studies. Parents turned to faith, religion and often prayer to call upon a ‘higher power’ for support, and felt comforted when procedures were successful, attributing this to divine intervention: “What kept me calm in the pre-operating area was praying” (Wei et al. 2017). “I have faith in god and that’s the only way my husband and I can go through this. My family and I spent a lot of time praying and that helped calm us down” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017). Parents managed uncertainty around the birth outcome by turning to faith as well, putting their faith in their doctors: “We’ll just let God, put it in His hands and let the good doctors take care of it. That’s about all we can do” (Rempel et al. 2009).

Parental Management

This theme includes strategies and styles that parents adopted and wove into their everyday lives in order to adapt to and minimise the impact of CHD on family life.

Striving for Normality

Nearly all of the studies in this review referred to a sense of gaining or maintaining normality, and not turning the child’s condition into a reason to treat them differently. Parents who held this attitude reported coping with the diagnosis by not acknowledging it in their day-to-day life: “Raise the child as if they are going to live. Do not treat them as if they are going to die…. Do not disable them by using their health as an excuse” (Sira et al. 2014). “Actually we usually forget the fact that he had heart disease and that he needed an operation. We considered him normal” (Lan et al. 2007). This attitude was reinforced by professional advice to new parents: “They never told us, ‘Take this baby home, coddle her, and never let her do anything.’ That was not how her doctor thought this worked. Let her do what she wants to, let her live a life. If it’s two months that she lives, fine; if it’s two years that she lives, fine. Let her live that life and that’s the way we felt, too” (Gantt 2002). When offering advice based on their own experiences, the same ideas were given for others to consider: “Live normally. Let your family continue on as normal as possible, because the rest of the world is not going to give one hoot that this kid’s got this heart defect. So don’t let him use it as an excuse. Think positive; hold the vision of good results, and just, you know, deal with it and weave it into your life and your family as normally as possible” (Gantt 2002).

Becoming Experts

This theme features parents’ reports of preparing themselves and their families for welcoming a child with CHD into their lives, by researching information, preparing their home and getting themselves ready to take on the increased care load of a child with often complex health issues. Parents acknowledged the pressure on them once they left the hospital and had to meet their child’s care needs at home, and how they gradually learned about procedures and checks, becoming experts in their child’s condition: “It was a little scary at first. I checked him numerous times a day. I felt very comfortable’cause I had all the equipment I needed at home and the more he stayed at home, the more we got to know him… Being home is different’cause you don’t have a nurse that you can just run to… I kind of became his nurse while I’m his mom and actually got more comfortable [as each] week went by” (Rempel et al. 2012).

Hypervigilance

Parents described coping with their new responsibility of ensuring the health of their child by increased monitoring and checking for any signs and symptoms that would suggest deterioration in health or delayed development. Some became regimented with the medications so they knew that their child was taking exactly what they needed: “I was a fanatic about the medications, you know, that had to be at – the drops at this time and not a minute after” (Meakins et al. 2015).

Hypervigilance was heightened when parents took their children home and they did not have hospital staff to turn to for reassurance: “You just feel like you have a job. I mean your job is very important, even as just a parent of a normal healthy child but it’s not as stressful. You don’t have to worry about did they get their medicine? Are they going to be okay today? Are they going to stop breathing and turn blue?… I’ve got to worry about this NG [nasogastric] tube. Is he going to throw it up today? Is he going to pull it out today?” (Rempel et al. 2012). Even when doctors had reassured parents they did not need to do as many checks, they still continued for their own peace of mind: “So every day, we wrote down his weight and his [oxygen] sats, his saturations [between first and second surgery]. Now [after second surgery], we were not told we had to do it every day, but we did it anyway, just for peace of mind for ourselves” (Meakins et al. 2015).

Avoidance

This theme contains coping styles utilised mainly in the early stages of CHD, such as when a diagnosis has been made in pregnancy, when parents are given the decision of proceeding with surgery and/or when their child is actually undergoing the surgical procedures. The theme of avoidance covers strategies of parents accepting that they are not responsible for everything, denial of the diagnosis, and using distraction techniques to reduce the time and intensity of worry.

“It’s out of my hands”

Parents reported a sense of allowing big events, such as life-saving surgery, just to proceed without trying to control it too much, because they felt that they could not influence the outcome themselves. They relinquished this responsibility onto the surgeons and left their child in their hands: “Sure, we had to sign a consent and such, but there really wasn’t a choice. I looked at it like: A) We cannot have the surgery and our son will die or B) We can do the surgery and there’s a chance that he will live” (Harvey et al. 2013).

Parents also acknowledged that they were physically unable to do everything for themselves and their families, so eventually handed over some aspects of their roles to others in order to cope: “I am not only a parent, I am apparently also just a human with limitation, and I cannot go around the clock [sic] and at the same time doing my job… as it has been for me, my mother was babysitting, so I could go to sleep or work” (Bruce et al. 2014).

Akin to the theme of support through faith, some parents reported believing in handing their child’s fate over to a ‘higher power’ and trusting in God’s plan for them: “I don’t know if I believe in destiny or if I just have a lot of faith, but when there’s nothing else you can do, I had to believe that whatever was supposed to happen, would happen” (Harvey et al. 2013). Whether the outcome for the child was positive or not, parents reported: “For whatever reason (I thank God), on this day < of surgery > I felt like I could take it if our son did not survive. We were doing all that we could to give him a heck of a chance but you can’t fight fate” (Harvey et al. 2013).

Privacy

This theme related to parents managing by not sharing information about the diagnosis; for example, limiting how much they told people who asked about the pregnancy: “So there’s nothing to be ashamed of. And we know that. But we also know that not everybody that talks to me and asks how far along needs to know” (McKechnie et al. 2015). This theme continued when the child was born and underwent surgery.

Denial/distraction

In the early stages, once parents received the diagnosis of their unborn child’s heart condition, several reported trying to ignore or deny that there was a problem. The pregnancy felt normal to them, but appointments reminded them of the diagnosis.

During the long stays in the intensive care unit, parents reported that they needed something to distract them in order to reduce or avoid the worrying thoughts about what could happen: “I’ve been playing cards here just to get my mind off. I’ll go down and sit with my son for a while and then when I cannot sit anymore I’ll say to another mom- let’s go and play some cards, I feel stressed” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017). These passive coping mechanisms seemed to help distract parents from the severity of the situation and gave them a chance to recuperate: “As hard as it’s been, there were two times that my husband and I have gone, left and ate dinner somewhere. Not fancy, just not in the cafeteria. We even had a beer one night. It felt really good. The next day I was ready to restart dealing with this” (Golfenshtein et al. 2017).

Discussion

These 22 studies from 7 countries were systematically reviewed and their methodological quality was assessed. By drawing together experiences during pregnancy, through surgeries and parenting later in childhood, this synthesis provides a more comprehensive understanding of the various facets of coping that vary over time, reported qualitatively using parents’ own words.

Parents who received a diagnosis during pregnancy had the additional stressor and responsibility of making a decision to proceed with the pregnancy knowing that their child would have a chronic condition. This period of time was exemplified by using emotional coping strategies, such as optimism, attachment (or detachment) to their unborn child, and expressing their grief at the diagnosis. Some parents turned to their partners for support and did not tend to invite others to share in this experience because this would expose the reality of their circumstances. Some parents began gathering information to learn about the condition while others employed avoidance strategies so they only had to deal with the condition once they knew the severity (Lalor et al. 2008). Parents who received a diagnosis at birth bypassed the period of uncertainty during pregnancy, but had to face the reality of having a child with a heart condition requiring surgery when they had been expecting a healthy baby. The period between birth and surgery may have been short, and so parents had to adapt much quicker than those who already had the diagnosis before birth. Unequivocally, parents reported coping with the management of CHD by doing their best to integrate it into their lives without it taking over, and leading normal lives whenever possible. Nevertheless, many parents reported developing hypervigilance to any symptoms suggestive of deterioration in the health of their child – an adaptive and entirely appropriate strategy. Parents became experts in their child’s condition, learning about their healthcare needs and developing an understanding of what symptoms indicated the need for medical attention and what was just normal for their child.

Findings from this review concur with a review of 29 studies to determine supportive care needs of parents with children with rare diseases (Pelentsov et al. 2015) in relation to social, informational and emotional needs. Similar findings relating to parental vigilance and information seeking, as well as support from religious beliefs emerged in reviews of other chronic childhood conditions (Coffey 2006; Tong et al. 2008). Mothers of children with other foetal abnormalities use similar coping styles to those reported in the synthesis (Brisch et al. 2003; Lalor et al. 2009), particularly the emergence of hope in the face of unfavourable odds (Bally et al. 2018). The idea of coping with the condition by treating the child as normal, or maintaining a normal family life echoes findings from other reviews of children with chronic illness (Fisher 2001). However, it is evident that alongside striving for normality, parents remain vigilant and watchful for signs of potential ill health, when their child has a chronic condition (Niedel et al. 2013) which can be appropriate and adaptive.

The findings are also concordant with those of other studies and reviews (Jackson et al. 2015; Shudy et al. 2006) on this research topic in terms of drawing on social support as a strategy for coping. The theme of support was evident although it ranged from support within the couple to the wider family, to seeking out and accessing support from other parents who were going through similar experiences. This provides parents with a shared social identity and enables them to learn from the experiences of others (Shilling et al. 2013), and use of peer support groups has been found to benefit parents across a range of chronic health conditions (Kerr and McIntosh 2000; Shilling et al. 2015; Tong et al. 2008), both online and in person (Bray et al. 2017). An emergent theme was the use of faith and spirituality to cope with unknown or difficult experiences, which has been shown to support parent coping (Raingruber and Milstein 2007).

There is little qualitative evidence in other conditions that supports the use of denial or distraction as a coping style: this is often labelled as dysfunctional or maladaptive on measures (Carver et al. 1989). However, in the unique environment of theatre and paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), there is little else that parents are able to draw on.

In terms of limitations, it is important to consider that the samples were usually drawn from single heart centres linked to the researchers; thus, there might be differences within that country itself based on the provision of care, especially in countries where health care is privatised. Most parents were married or living with a partner, so these findings do not account for single parent families who may face additional or different challenges to cope with. Although this review aimed to explore parental coping, mothers outnumbered fathers in the studies by 3:1, a common limitation in paediatric psychology research (Phares et al. 2005). It was apparent from the demographic data that though studies may aim to explore the “parent” experience, the number of mothers drastically outnumbers the number of fathers in inclusive studies.Finally, all of the studies used convenience or purposive sampling which is highly vulnerable to selection bias because it may not be representative of the population (Etikan et al. 2016).

The findings of this review have clear clinical implications for services that come into contact with parents of children with CHD. There is a grief and stress reaction at the time of diagnosis (George et al. 2007) when parents must adjust to the presence of the condition (Grootenhuis and Last 1997a); this varies as parents begin to passively or proactively cope with the condition and continues throughout on-going health care, developmental transition stages and any hospitalisations and bouts of severe illness (Melnyk et al. 2001), which health care professionals need to be aware of in their interactions with families. It may be beneficial to make distractions available to parents during the surgical and recovery period, and give them “permission” to take a break, as they may feel obliged to stay in the hospital even though there is nothing they can do.

Many parents report drawing on the psychosocial support available to them in the form of wider family and friends. When families exceed their psychosocial resources due to stressful events, whether related to the condition or other life stressors, they may need psychologically minded professionals to notice their need and offer support. It is therefore imperative, when working with children with CHD, to consider the whole family system (Emerson and Bögels 2017) because their wellbeing and vulnerabilities can have a direct impact on the wellbeing of the child (Vonneilich et al. 2016). There is evidence supporting the use of group to specifically support parents of children with CHD (Barnett et al. 2003), which are usually run by a clinical psychologist who could provide additional input for families where appropriate and indicated. These have the benefit of widening parents’ peer support network, hearing stories of survival and strategies for dealing with stress, as well as normalising their and their child’s experiences.

In conclusion, parents of children with CHD are more vulnerable to psychological and social distress, and the strain of the condition can impact the family at different points along the journey from diagnosis into childhood. This review demonstrates that while there are common themes of coping in parents, individuals employ their own styles and strategies based on prior experience, availability of social support, personal characteristics and beliefs. Their coping styles draw on their existing resilience and support networks. Once children enter the surgical phases, parents draw on existing individual resources and their support network. Parents try to maintain a sense of normality, integrating CHD into their lives without it having a major impact except at times of transition and hospitalisation when they must call upon additional strategies or supports to manage this stress.

References

Ailes, E. C., Gilboa, S. M., Riehle-Colarusso, T., Johnson, C. Y., Hobbs, C. A., Correa, A. & Honein, M. A. (2014). Prenatal diagnosis of nonsyndromic congenital heart defects. Prenatal Diagnosis, 34(3), 214–222.

Al-Busaidi, Z. Q. (2008). Qualitative research and its uses in health care. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 8(1), 11–19.

Alkan, F., Sertcelik, T., Yalın Sapmaz, S., Eser, E. & Coskun, S. (2017). Responses of mothers of children with CHD: quality of life, anxiety and depression, parental attitudes, family functionality. Cardiology in the Young, 27(9), 1748–1754.

Bajracharya, S. & Shrestha, A. (2016). Parental coping mechanisms in children with congenital heart disease at tertiary cardiac centre. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences, 7(4), 75–79.

Bally, J. M. G., Smith, N. R., Holtslander, L., Duncan, V., Hodgson-Viden, H., Mpofu, C. & Zimmer, M. (2018). A metasynthesis: Uncovering what is known about the experiences of families with children who have life-limiting and life-threatening illnesses. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 38, 88–98.

Barnett-Page, E. & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 59.

Barnett, D., Clements, M., Kaplan-Estrin, M. & Fialka, J. (2003). Building new dreams: Supporting parents’ adaptation to their child with special needs. Infants & Young Children, 16(3), 184–200.

Bernier, P. L., Stefanescu, A., Samoukovic, G. & Tchervenkov, C. I. (2010). The challenge of congenital heart disease worldwide: Epidemiologic and demographic facts. Seminars in Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgery: Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Annual, 13(1), 26–34.

Booth, A., Clarke, M., Dooley, G., Ghersi, D., Moher, D., Petticrew, M. & Stewart, L. (2012). The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 1(1), 2.

Bray, L., Carter, B., Sanders, C., Blake, L. & Keegan, K. (2017). Parent-to-parent peer support for parents of children with a disability: A mixed method study. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(8), 1537–1543.

Brisch, K. H., Munz, D., Bemmerer-Mayer, K., Terinde, R., Kreienberg, R. & Kächele, H. (2003). Coping styles of pregnant women after prenatal ultrasound screening for fetal malformation. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(2), 91–97.

Brosig, C. L., Whitstone, B. N., Frommelt, M. A., Frisbee, S. J. & Leuthner, S. R. (2007). Psychological distress in parents of children with severe congenital heart disease: the impact of prenatal versus postnatal diagnosis. Journal of Perinatology, 27(11), 687–692.

Bruce, E., Lilja, C. & Sundin, K. (2014). Mothers’ lived experiences of support when living with young children with congenital heart defects. Journal For Specialists In Pediatric Nursing, 19(1), 54–67.

Cantwell-Bartl, A. M. & Tibballs, J. (2013). Psychosocial experiences of parents of infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 14(9), 869–875.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267.

Coffey, J. S. (2006). Parenting a child with chronic illness: a metasynthesis. Pediatric Nursing, 32(1), 51–59.

Cooke, A., Smith, D. & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443.

Cousino, M. K. & Hazen, R. A. (2013). Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(8), 809–828.

Doherty, N. & Utens, E. M. W. J. (2016). A family affair. In Christopher McCusker, Frank Casey (Eds.), Congenital heart disease and neurodevelopment: understanding and improving outcomes (pp. 107–117). Elsevier/Academic Press, University Medical Centre, Rotherdam, UK.

Emerson, L. M. & Bögels, S. (2017). A systemic approach to pediatric chronic health conditions: why we need to address parental stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2347–2348.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A. & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4.

Felton, B. J., Revenson, T. A. & Hinrichsen, G. A. (1984). Stress and coping in the explanation of psychological adjustment among chronically ill adults. Socila Science & Medicine, 18(10), 889–898.

Fisher, H. R. (2001). The needs of parents with chronically sick children: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(4), 600–607.

Flemming, K. & Briggs, M. (2007). Electronic searching to locate qualitative research: Evaluation of three strategies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(1), 95–100.

Gantt, L. (2002). As normal a life as possible: Mothers and their daughters with congenital heart disease. Health Care for Women International, 23(5), 481–491.

George, A., Vickers, M. H., Wilkes, L. & Barton, B. (2007). Chronic grief: Experiences of working parents of children with chronic illness. Contemporary Nurse, 23(2), 228–242.

Goldberg, S., Morris, P., Simmons, R. J., Fowler, R. S. & Levison, H. (1990). Chronic illness in infancy and parenting stress: A comparison of three groups of parents 1. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 15(3), 347–358.

Golfenshtein, N., Deatrick, J. A., Lisanti, A. J. & Medoff-Cooper, B. (2017). Coping with the stress in the cardiac intensive care unit: can mindfulness be the answer? Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 37, 117–126.

Grootenhuis, M. A. & Last, B. F. (1997a). Adjustment and coping by parents of children with cancer: a review of the literature. Supportive Care in Cancer, 5(6), 466–484.

Grootenhuis, M. A. & Last, B. F. (1997b). Predictors of parental emotional adjustment to childhood cancer. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 6(2), 115–128.

Gudmundsdottir, M., Gilliss, C. L., Sparacino, P. S., Tong, E. M., Messias, D. K. & Foote, D. (1996). Congenital heart defects and parent-adolescent coping. Families, Systems, & Health, 14(2), 245–255.

Hannes, K. (2011). Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In Noyes, J., Booth, A., Hannes, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Lewin, S. & Lockwood, C. (Eds.), Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in cochrane systematic reviews of interventions, Version 1. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance.

Harvey, K. A., Kovalesky, A., Woods, R. K. & Loan, L. A. (2013). Experiences of mothers of infants with congenital heart disease before, during, and after complex cardiac surgery. Heart & Lung, 42(6), 399–406.

Jackson, A. C., Frydenberg, E., Liang, R. P., Higgins, R. O. & Murphy, B. M. (2015). Familial impact and coping with child heart disease: A systematic review. Pediatric Cardiology, 36(4), 695–712.

Kendall, L., Sloper, P., Lewin, R. J. & Parsons, J. M. (2003). The views of parents concerning the planning of services for rehabilitation of families of children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiology in the Young, 13(1), 20–27.

Kerr, S. M. & McIntosh, J. (2000). Coping when a child has a disability: Exploring the impact of parent-to-parent support. Child: Care, Health and Development, 26(4), 309–322.

Kosta, L., Harms, L., Franich-Ray, C., Anderson, V., Northam, E., Cochrane, A., Menahem, S. & Jordan, B. (2015). Parental experiences of their infant’s hospitalization for cardiac surgery. Child: Care, Health & Development, 41(6), 1057–1065.

Lalor, J., Begley, C. M. & Galavan, E. (2008). A grounded theory study of information preference and coping styles following antenatal diagnosis of foetal abnormality. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(2), 185–194.

Lalor, J., Begley, C. M. & Galavan, E. (2009). Recasting hope: A process of adaptation following fetal anomaly diagnosis. Social Science & Medicine, 68(3), 462–472.

Lan, S. F., Mu, P. F. & Hsieh, K.-S. (2007). Maternal experiences making a decision about heart surgery for their young children with congenital heart disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(12), 2323–2330.

Lawoko, S. & Soares, J. J. F. (2002). Distress and hopelessness among parents of children with congenital heart disease, parents of children with other diseases, and parents of healthy children. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(4), 193–208.

Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1(3), 141–169.

Leuthner, S., Bolger, M., Frommelt, M. & Nelson, R. (2003). The impact of abnormal fetal echocardiography on expectant parents’ experience of pregnancy: A pilot study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 24(2), 121–129.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J. & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), p. e1000100.

McKechnie, A. C. & Pridham, K. (2012). Preparing heart and mind following prenatal diagnosis of complex congenital heart defect. Qualitative Health Research, 22(12), 1694–1706.

McKechnie, A. C., Pridham, K. & Tluczek, A. (2015). Preparing heart and mind for becoming a parent following a diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1182–1198.

McKechnie, A. C., Pridham, K. & Tluczek, A. (2016). Walking the “Emotional Tightrope” from pregnancy to parenthood: Understanding parental motivation to manage health care and distress after a fetal diagnosis of complex congenital heart disease. Journal of Family Nursing, 22(1), 74.

Meakins, L., Ray, L., Hegadoren, K., Rogers, L. G. & Rempel, G. R. (2015). Parental vigilance in caring for their children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatric Nursing, 41(1), 31–41. 50.

Melnyk, B. M., Feinstein, N. F., Moldenhouer, Z. & Small, L. (2001). Coping in parents of children who are chronically ill: Strategies for assessment and intervention. Pediatric Nursing, 27(6), 548.

Moss, R. & Billings, A. (1982). Conceptualizing and measuring coping resources and processes. In L. Goldberger & S. Breznitz (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects (pp. 212–230). New York, NY: Free Press.

Mussatto, K. (2006). Adaptation of the child and family to life with a chronic illness. Cardiology in the Young, 16(S3), 110–116.

Nakazuru, A., Sato, N. & Nakamura, N. (2017). Stress and coping in Japanese mothers whose infants required congenital heart disease surgery. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 23, p.e12550.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2016). End of life care for infants, children and young people with life-limiting conditions: planning and management. NICE guideline [NG61]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng61

Niedel, S., Traynor, M., McKee, M. & Grey, M. (2013). Parallel vigilance: Parents’ dual focus following diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes mellitus in their young child. Health, 17(3), 246–265.

Noblit, G. & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography synthesizing qualitative studies (Sage university paper). Newbury Park, California, London: Sage.

Pelentsov, L. J., Laws, T. A. & Esterman, A. J. (2015). The supportive care needs of parents caring for a child with a rare disease: A scoping review. Disability Health Journal, 8(4), 475–491.

Phares, V., Lopez, E., Fields, S., Kamboukos, D. & Duhig, A. M. (2005). Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(8), 631–643.

Pope, C. & Mays, N. (1995). Qualitative research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ, 311(6996), 42–45.

Raingruber, B. & Milstein, J. (2007). Searching for circles of meaning and using spiritual experiences to help parents of infants with life-threatening illness cope. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 25(1), 39–49.

Rempel, G. R., Blythe, C., Rogers, L. G. & Ravindran, V. (2012). The process of family management when a baby is diagnosed with a lethal congenital condition. Journal of Family Nursing, 18(1), 35–64.

Rempel, G. R. & Harrison, M. J. (2007). Safeguarding precarious survival: Parenting children who have life-threatening heart disease. Qualitative Health Research, 17(6), 824–837.

Rempel, G. R., Harrison, M. J. & Williamson, D. L. (2009). Is “Treat your child normally” helpful advice for parents of survivors of treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome? Cardiology in the Young, 19(2), 135–144.

Rempel, G. R., Ravindran, V., Rogers, L. G. & Magill-Evans, J. (2013). Parenting under pressure: a grounded theory of parenting young children with life-threatening congenital heart disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(3), 619–630.

Rempel, G. R., Rogers, L. G., Ravindran, V. & Magill-Evans, J. (2012). Facets of parenting a child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nursing Research and Practice, 2012, 9.

Sawyer, M. & Spurrier, N. (1996). Families, parents and chronic childhood illness. Family Matters, 44(1), 12–15.

Seideman, R. Y., Watson, M. A., Corff, K. E., Odle, P., Haase, J. & Bowerman, J. L. (1997). Parent stress and coping in NICU and PICU. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 12(3), 169–177.

Shilling, V., Bailey, S., Logan, S. & Morris, C. (2015). Peer support for parents of disabled children part 1: perceived outcomes of a one-to-one service, a qualitative study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(4), 524–536.

Shilling, V., Morris, C., Thompson-Coon, J., Ukoumunne, O., Rogers, M. & Logan, S. (2013). Peer support for parents of children with chronic disabling conditions: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 55(7), 602–609.

Shudy, M., de Almeida, M. L., Ly, S., Landon, C., Groft, S., Jenkins, T. L. & Nicholson, C. E. (2006). Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: A systematic literature review. Pediatrics, 118(Suppl. 3), S203–S218.

Sin, S. (2010). Considerations of quality in phenomenographic research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(4), 305–319.

Sira, N., Desai, P. P., Sullivan, K. J. & Hannon, D. W. (2014). Coping strategies in mothers of children with heart defects: A closer look into spirituality and internet utilization. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(5), 606–622.

Snyder, C. R. (2014). Coping: The psychology of what works. Cary, United States: Oxford University Press.

Soulvie, M. A., Desai, P. P., White, C. P. & Sullivan, B. N. (2012). Psychological distress experienced by parents of young children with congenital heart defects: A comprehensive review of literature. Journal of Social Service Research, 38(4), 484–502.

Spijkerboer, A. W., Helbing, W. A., Bogers, A., Van Domburg, R. T., Verhulst, F. C. & Utens, E. (2007). Long-term psychological distress, and styles of coping, in parents of children and adolescents who underwent invasive treatment for congenital cardiac disease. Cardiology in the Young, 17(6), 638–645.

Tak, Y. R. & McCubbin, M. (2002). Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s congenital heart disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39(2), 190–198. 199p.

Tong, A., Lowe, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. C. (2008). Experiences of parents who have children with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics, 121(2), 349–360.

Utens, E. M., Versluis-Den Bieman, H. J., Verhulst, F. C., Witsenburg, M., Bogers, A. J. & Hess, J. (2000). Psychological distress and styles of coping in parents of children awaiting elective cardiac surgery. Cardiology in the Young, 10(3), 239–244.

van der Linde, D., Konings, E. E. M., Slager, M. A., Witsenburg, M., Helbing, W. A., Takkenberg, J. J. M. & Roos-Hesselink, J. W. (2011). Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58(21), 2241–2247.

Vonneilich, N., Lüdecke, D. & Kofahl, C. (2016). The impact of care on family and health-related quality of life of parents with chronically ill and disabled children. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(8), 761–767.

Walsh, D. & Downe, S. (2006). Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery, 22(2), 108–119.

Wei, H., Roscigno, C. I., Hanson, C. C. & Swanson, K. M. (2015). Families of children with congenital heart disease: A literature review. Heart & Lung, 44(6), 494–511.

Wei, H., Roscigno, C. I. & Swanson, K. M. (2017). Healthcare providers’ caring: Nothing is too small for parents and children hospitalized for heart surgery. Heart & Lung, 46(3), 166–171.

Werner, H., Latal, B., Valsangiacomo Buechel, E., Beck, I. & Landolt, M. A. (2014). The impact of an infant’s severe congenital heart disease on the family: a prospective cohort study. Congenital Heart Disease, 9(3), 203–210.

Wray, J. & Maynard, L. (2005). Living with congenital or acquired cardiac disease in childhood: Maternal perceptions of the impact on the child and family. Cardiology in the Young, 15(02), 133–140.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gokce Cokamay Yilmaz and Katie Carpenter for screening papers and quality appraising for this review.

Author Contributions

M.R.L. designed and executed the study, completed the data analyses, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. D.M.S. collaborated analysis, writing up of the data and contributed to all drafts. A.W. assisted in the development of the review idea, oversaw the review process, and collaborated in the writing and editing of all drafts of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lumsden, M.R., Smith, D.M. & Wittkowski, A. Coping in Parents of Children with Congenital Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-synthesis. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1736–1753 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01406-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01406-8