Abstract

In this work, we have studied the relative stability of 1,2- and 2,3-quinones. While 1,2-quinones have a closed-shell singlet ground state, the ground state for the studied 2,3-isomers is open-shell singlet, except for 2,3-naphthaquinone that has a closed-shell singlet ground state. In all cases, 1,2-quinones are more stable than their 2,3-counterparts. We analyzed the reasons for the higher stability of the 1,2-isomers through energy decomposition analysis in the framework of Kohn–Sham molecular orbital theory. The results showed that we have to trace the origin of 1,2-quinones’ enhanced stability to the more efficient bonding in the π-electron system due to more favorable overlap between the SOMOπ of the ·C4n−2H2n–CH·· and ··CH–CO–CO· fragments in the 1,2-arrangement. Furthermore, whereas 1,2-quinones present a constant trend with their elongation for all analyzed properties (geometric, energetic, and electronic), 2,3-quinone derivatives present a substantial breaking in monotonicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Quinones belong to the class of π-electron chemical compounds in which two units of CH are replaced by two carbonyl groups that have to be located in a way that does not lead to ionic canonical structures or in other words to form “a fully conjugated cyclic dione structure” [1]. In most cases, location of carbonyl group is either in the ortho- or in the para-type positions. Derivatives of quinones are common constituents of biologically important molecules as ubiquinone, which is important for aerobic respiration [2], or phylloquinone known as vitamin K [3]. In protic solvents, quinones are easily reducible to hydroquinones, whereas in aprotic solvents, they are electrochemically reduced to radical anions [4, 5]. A very important structural property of quinones is that the two carbonyl groups attached to a benzenoid ring system cause a very strong localization of the π-electron structure, i.e., decrease in aromaticity. In the case of ortho-benzoquinone, many aromaticity indices such as HOMA [6, 7], MCI [8, 9] or FLU [10] indicated antiaromatic properties of the ring [11] in contrast to benzene ring known as the archetypic aromatic π-electron system [12–15]. Moreover, the HOMA [6, 7] values for the ring with the two CO groups are −1.353 and −1.277 for 1,2- and 2,3-naphthoquinone [16], respectively, indicating antiaromaticity, whereas HOMA for the ring in naphthalene amounts to 0.811 [17].

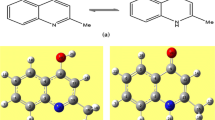

Since the localization effect of the quinoid fragment is well known, the question may be posed: how far the localization impact of the ortho-quinoid fragment may affect further rings in 1,2- and 2,3-quinone derivatives of acenes? Then, the systems of this study are 1,2- (Scheme 1) and 2,3-quinone (Scheme 2) derivatives of linear benzenoids (Scheme 3). It is worth noting that a previous study on the aromaticity of pentalenoquinones already indicated that the relative position of the two C=O fragments has a large influence on the aromaticity of these pentalenoquinones [18].

2 Computational methods

2.1 Geometry optimizations

The full geometry optimization of the set of systems shown in Schemes 1, 2 and 3 was performed using B3LYP hybrid functional [19–21] in conjunction with the 6-311+G(d) basis set [22, 23]. For equilibrium structures, a frequency analysis was performed in order to check whether all geometries corresponded to true ground state stationary points. Gaussian 09 [24] software package was used for this part of calculations. For open-shell systems, unrestricted UB3LYP/6-311+G(d) calculations with broken symmetry (using guess = mix option) were also performed. It appeared that for 2,3-anthraquinone and its larger analogues (tetra-, penta-, and hexa-ones), the lowest energy state corresponds to the diradical singlet state. Stability of their wavefunctions constructed from Kohn–Sham orbitals was also checked. All wavefunctions were found to be stable.

Accurate calculations of large open-shell systems are difficult and expensive; therefore, DFT methods are commonly used. The good performance of the UB3LYP method is confirmed by recent papers [25–30]. On the basis of previous results [31], spin contamination corrections were not included.

2.2 Stability analysis

The difference between electronic energies of 1,2-(E 1,2) and 2,3-(E 2,3) quinone derivatives of linear benzenoids allows to compare their relative stability:

The same analysis can be done through comparison of stabilization energies ΔE 1,2 and ΔE 2,3, which can be estimated for the reaction:

Therefore, the stabilization energies are expressed as follows:

It should be mentioned that in order to have the consistent model of reaction (2), we used in this scheme the singlet state energy of O2 molecule, having in mind the fact that the triplet state is the most stable form of that species.

2.3 Energy decomposition analysis

The Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF) program [32–34] was used to carry out energy decomposition analysis (EDA) in the framework of Kohn–Sham molecular orbital (MO) theory in single-point energy calculations using the B3LYP/6-311+G(d) geometries. All ADF calculations were carried out using the B3LYP functional [19–21] with the TZ2P basis set.

Each molecule of quinone (for both 1,2- and 2,3-series) can be divided into two fragments,·C4n-2H2n–CH·· (2-methtriyl-aryl, n = 1–6) and ··CH–CO–CO· (1,3,3-tridehydro-2-oxopropanal) in their quadruplet state, equivalent for both isomers. As an example, naphthoquinone is presented in Scheme 4. The energy of such reaction is equal to the total bonding energy, ΔE BE, computed as the energy difference between the mentioned molecule and the sum of the energies of the relaxed fragments. ΔE BE is composed of two components: (1) the preparation energy, also known as deformation energy, ΔE def, and (2) the interaction energy, ΔE int. The former component is always positive because it describes the amount of energy required to deform the fragments from their relaxed geometry to the one they acquire in the final molecule. The latter term is focused on the interaction between the deformed fragments, i.e., the fragments in the geometry they adopt in the studied molecule. ΔE int may be then divided in the framework of the Kohn–Sham MO model by using a quantitative EDA [35–40] into electrostatic interaction (ΔV elstat), Pauli repulsive orbital interactions (ΔE Pauli), and attractive orbital interactions (ΔE oi):

Moreover, using the extended transition state (ETS) scheme [37, 38], the ΔE oi term can be divided into the contributions of orbitals with different symmetry. For planar systems, like the ones under analysis in the present work, the σ/π separation is possible:

General theoretical background on the bond energy decomposition scheme used here (Morokuma–Ziegler) can be found in the papers by Bickelhaupt and Baerends [39, 41]. Finally, in the EDA of the bonding energy, open-shell fragments were treated with the spin-unrestricted formalism, but for technical reasons, spin polarization cannot be included. This error causes the studied interaction to become in the order of a few kcal/mol stronger. To facilitate a straightforward comparison, the EDA results were scaled to match exactly the regular bond energies. This scaling by a factor in the range 0.91–0.93 in all model systems does not affect trends.

At this point, it must be mentioned that it has been technically not possible to undertake the EDA calculations for singlet open-shell systems. Application of EDA to singlet open-shell systems leads always to singlet closed-shell results. Therefore, to estimate the results of the EDA for singlet open-shell systems, i.e., 2,3-quinones with 3 ≤ n ≤ 6, we decomposed the bonding energy of singlet closed-shell 2,3-quinones and applied some corrections. In particular, we assumed that ΔV elstat and ΔE Pauli energies for open- and closed-shell singlet species are the same, and only the orbital interaction (ΔE oi) term is corrected. For this purpose, the energy difference between values for the whole system at singlet open-shell and closed-shell computations is taken into account (added to the ΔE oi term). ΔE σ and ΔE π were also corrected by using the ratio ΔE σ(open)/ΔE oi(open) = ΔE σ(closed)/ΔE oi(closed) and ΔE π(open)/ΔE oi(open) = ΔE π(closed)/ΔE oi(closed), where corrected ΔE oi is used (for such correction ΔE σ + ΔE π = ΔE oi).

2.4 π-Electron delocalization analysis

Two types of aromaticity parameters have been used as quantitative measures of π-electron delocalization: (1) structural and (2) electronic based indices.

First, HOMA [6, 7], the geometry-based aromaticity index, may serve as a convenient, reliable [42], and easily accessible quantitative measure of π-electron delocalization [43] of the system (e.g., in the ring). The formula can be written as:

where n is the number of bonds taken into the summation; α j is a normalization constant (for CC and CO bonds α CC = 257.7 and α CO = 157.38) fixed to give HOMA = 0 for a model non-aromatic system and HOMA = 1 for a system with all bonds equal to the optimal value R opt,j, assumed to be realized for fully aromatic systems (for CC and CO bonds R opt,CC = 1.388 and R opt,CO = 1.265 Å), whereas R j denotes bond lengths taken into calculation.

Second, electronic aromaticity criteria using the atomic partition provided by the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) [44] have been applied: the aromatic fluctuation index (FLU) [10] and the multicenter index (MCI) [8, 9].

FLU measures the amount of electron sharing between contiguous atoms. It is defined as:

where A 0 ≡ A N (N being the number of atoms in the ring) and V(A i) is the atomic valence given by:

and α is a simple function to make sure that the first term in Eq. (8) is always greater or equal to 1, so it takes the values:

The δ ref(C,C) = 1.389 e, calculated from benzene at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level, was used in the calculations. FLU is close to 0 in aromatic species and differs from it in non-aromatic ones.

MCI is derived from the I ring index that was defined by Giambiagi et al. [45] as:

where S ij(A k) is the overlap between MOs i and j within the domain of atom k. In this formula, it is considered that the ring is formed by atoms in the string {A} = {A 1 , A 2 , … A N }. Extension of this I ring index of Giambiagi by Bultinck and coworkers resulted in the so-called MCI index

where P(A) stands for the N! permutations of the elements in the string {A}. The MCI index has been successfully applied to a broad number of situations, from simple organic compounds to complex all metal clusters with multiple aromaticity [8, 46–56]. For planar species, S ij(A k) = 0 for i ∈ σ and j ∈ π orbital symmetries; thus, MCI can be exactly split into σ- and π-contributions, namely MCIσ and MCIπ, respectively. When computed in an aromatic ring, the more positive the MCI, the more aromatic the ring.

FLU, I ring, and MCI indices have been obtained with the ESI-3D program [10, 57].

2.5 Hardness

The hardness of a chemical system, η, is a measure of the resistance of a chemical species to change its electronic configuration. It is defined as:

where N is the number of electrons of the system, and \( \nu \left( {\vec{r}} \right) \) is the potential acting on an electron at \( \vec{r} \) due to the nuclear attraction plus such other external forces as may be present. A three points finite difference approximation for the derivative leads to the following working definition when considering the Koopmans’ approximation: [58]

where ε LUMO and ε HOMO are the energies of the LUMO and the HOMO orbitals.

3 Results and discussion

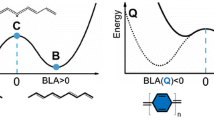

It was recently shown that the lowest energy state of higher polyacenes can correspond to diradical singlet state instead of the closed-shell singlet state [59–61]. Similar results are also observed for some studied quinones. Diradical singlet state of 2,3-anthraquinone and its larger analogues (n ≥ 3, n being the number of the rings), obtained using the unrestricted broken symmetry UB3LYP/6-311+G(d) method, is found to be more stable than the closed-shell singlet state; the energy differences amount to 5.2, 15.9, 12.1, and 10.2 kcal/mol for 2,3-anthra-, tetra-, penta-, and hexaquinones, respectively. This is similar to what is found for acenes [61], although in these latter cases, the closed-shell species are more stable until n < 5 or 6. The change in the electronic ground state can also be understood using the Clar’s π-sextet model [62]. This model, known also as Clar’s rule, offers a qualitative picture of the aromatic character of a particular ring in a polycyclic benzenoid hydrocarbon molecule. Its implementation allows to classify rings according to their π-electron structure into aromatic sextets, empty rings, migrating rings, and those with localized double bonds. Clar’s rule has been validated experimentally and successfully applied in many cases, for review see [63]. As can be seen in Scheme 5, by changing from closed-shell (no π-sextets) to open-shell singlet state, a π-bond is lost and this is partially or totally compensated by the formation of a migrating π-sextet and some 1,4 interaction (Dewar-type resonance structure). It should be noted that Clar structure shown in Scheme 5b is reinforced by all applied aromaticity indices (see Table S1 in Supporting Information). Summarizing, in 2,3-quinones for n > 2, the diradical singlet situation is favored, as in the case of the acenes [25, 59, 61, 63] and in other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [26–30, 64–69] and graphene nanoflakes [70, 71].

Therefore, for 2,3-isomers, only the results of the ground states (singlet closed shell for n ≤ 2 and singlet open shell for n ≥ 3) are presented below.

It is well known that structural data are one of the most important sources of information about molecules [72]. Therefore, before discussing the title question, let us look at the structural parameters of 1,2- and 2,3-quinone derivatives.

Ortho-quinoid groups are very important structural fragments in both series of quinones. In the case of 1,2-isomers (see Scheme 1), due to the lack of symmetry, the CO bonds may differ in lengths, whereas this is not the case for 2,3-isomers (Scheme 2). In 1,2-quinones, both CO elongate with increase in the number of rings (Fig. 1). Moreover, for quinones with n ≥ 2, C1O is always shorter than C2O. This difference can be rationalized by the use of the so-called Hammett–Streitwieser position constants [73], which describe the basicity of a given position for interactions with proton [74]. Their values for positions 1 and 2 in naphthalene are 0.35 and 0.25, respectively, indicating a greater basicity in position 1 and hence shorter C1O bonds. Similar data are also for positions 1 and 2 in anthracene (0.41 and 0.36, respectively).

Much more interesting is a scatter plot for 2,3-isomers presented in Fig. 1b. Even though both CO bonds have the same length, we observe important changes in their bond lengths for these particular derivatives. In this case, the range of the CO bond length variability amounts to 0.019 Å, whereas in the case of 1,2-derivatives, differences are <0.003 Å. Moreover, the shape of the presented relationships can be described by two linear equations: (1) with positive slope (0.0075) for the three shortest quinones and (2) with a negative slope (−0.0006) for the three longest isomers (the correlations coefficients amount to 0.960 and −0.995, respectively). The slope in the first case is almost 10 times greater than the observed for the second one and for 1,2-isomers. In other words, in 2,3-quinones with n ≤ 3, the CO bond lengthening is more sensitive to the enlargement of the molecule by an extra ring. Thus, we observe a clear different behavior between 1,2- and 2,3-quinones, with the change in trend for this latter found between n < 3 and n ≥ 3, which coincides with the change in the nature of the ground state referred above.

Structural data also allow to study π-electron delocalization; hence, the HOMA index is now the next tool used to investigate the differences between 1,2- and 2,3-quinone isomers of polycyclic acenes. Figure 2 presents the plots of the aromaticity index HOMAperimeter versus the number of the ring (n) for the two isomers of quinones; for comparison, data of linear benzenoid are also included. HOMAperimeter was calculated taking into account only bonds along the perimeter of the molecules thereby to describe the aromaticity of the whole molecule. Obtained values show that all quinone derivatives may be divided into two groups: (1) antiaromatic and (2) aromatic. In both cases, enlarging of the system results in increasing aromaticity (for the first group antiaromaticity decreases). It should be mentioned that the observed variability is similar for 1,2- and 2,3-quinone derivatives, although 1,2-anthraquinone is antiaromatic or non-aromatic, whereas its 2,3-analogue is slightly aromatic. Furthermore, the change from antiaromatic to aromatic character in 2,3-quinones takes place from n = 2 to n = 3, a behavior that coincides with the change in the nature of the ground state referred above (see Scheme 5). Additionally, obtained HOMAperimeter values indicate slightly greater aromaticity of 2,3- derivatives than 1,2-ones for molecules with n ≥ 3. In contrast with the aromaticity of the quinones measured with HOMAperimeter, the aromaticity of polyacenes decreases from 0.99 to 0.79 from benzene to hexacene, respectively.

HOMA values of particular rings in studied systems are presented in Fig. 3. If we first look at the ring containing the quinoid fragment (ring I in Schemes 1 and 2), we find that for 1,2-isomers the longer the quinone derivative, the lower its antiaromaticity (Fig. 3a). In the case of 2,3-derivatives, such trend is observed only for the four shortest quinones, whereas for the remaining molecules, the HOMA is almost constant (Fig. 3b). It should be noticed that antiaromaticity changes of the ring I correlate well with the observed CO bond length variations for both isomers. Thus, again, we can consider this case as two trends: for n < 3 (decrease in antiaromaticity) and n ≥ 3 (almost constant); with the lowest antiaromaticity corresponding to 2,3-tetraquinone. Interestingly, for n = 2, ring II is aromatic for 1,2-naphthoquinone, and it is non-aromatic for 2,3-naphthoquinone. This is the expected result from the Clar π-sextet rule as ring II of 1,2-naphthoquinone, unlike the 2,3-isomer, contains the π-sextet. In 2,3-quinones, for n ≥ 3, rings II and successive are aromatic as expected from the fact that a migrating π-sextet is generated in the diradicals (see Scheme 5). Finally, polyacenes present a monotonic decrease in aromaticity of ring I from benzene to hexacene (Fig. 3c).

For the remaining rings, the shapes of HOMA values in polyacenes and 1,2-quinone derivatives are quite similar, obviously not taking into consideration the ring I of quinones. Aromaticity of the middle ring is the largest in comparison with other rings of the molecule, and the elongation of the system causes a decrease in the aromaticity of all rings. In the case of 2,3-isomers, the most aromatic is the terminal ring of the molecule, although it is non-aromatic in 2,3-naphthoquinone (HOMA is close to 0.0).

Similar conclusions can be drawn from electronic aromaticity criteria FLU and MCI (see Figs S1 and S2) that support the above discussed conclusions drawn from geometry-based aromaticity values.

3.1 Which quinone isomer 1,2- or 2,3- is more stable?

Energy differences between the electronic and bonding energies of 1,2-quinone derivatives (Scheme 1) and their 2,3-counterparts (Scheme 2) lead to negative values (Eq. 1, see Fig. 4). In other words, 1,2-derivatives of quinone are always more stable than their corresponding 2,3-isomers. However, some strange peculiarity appears there again. As shown in Fig. 4, the variability of energy differences ΔE (Eq. 1) for both electronic and bonding energies is not monotonic, the largest differences being found for anthraquinone isomers. However, we found a monotonic decrease in absolute value of the energy differences starting from n = 3 (n values corresponding to 2,3-quinones with an open-shell singlet ground state).

Since polyacenes are mother compounds for both kinds of quinones (Scheme 3), it is reasonable to compare the stabilization energies of these latter estimated on the basis of the reaction in Eq. 2. The obtained results (see Fig. 5) are striking. The stabilization energies of the quinone isomers (Eqs. 3, 4) plotted against the number of rings (n) have completely different shapes. For 1,2-isomers with 1 ≤ n ≤ 6, the observed changes in ΔE 1,2 are monotonic (their stability increases with increasing n), whereas for 2,3-isomers, the energy differences ΔE 2,3 pass through a maximum (less negative values) for n = 2 and for n ≥ 3 follow the same trend of decreasing when n increases (Fig. 5). Thus, assuming the quinoid fragment fused to the polyacene molecule as a perturbation of polyacene electron structure, we observe that the resulting changes depend on the type of isomer.

3.2 Why 1,2-quinones are more stable than their 2,3-isomers?

To obtain a deeper insight into the origin of the relative stabilities of 1,2- and 2,3-quinones, an energy decomposition analysis was performed following the reaction presented in Scheme 4 with the corresponding fragments. It should be noted that both isomers can be constructed from two identical fragments, both in their quadruplet state in order to form the corresponding broken one single and one double bonds. However, to undertake the EDA analysis for singlet open-shell systems, i.e., 2,3-quinones with 3 ≤ n ≤ 6, appropriate corrections have to be applied for technical reasons (see Computational methods). Total bonding energies (ΔE BE) and all their components for both isomers are presented in Figs. 6, 7 and 8. Additionally, obtained results of the EDA analysis are gathered in Table S2 (see Supplementary Material).

First, 1,2-quinone derivatives show quite constant ΔE BE values (see Fig. 6). Their bonding energy range of variability is equal 7.8 kcal/mol (for 2 ≤ n ≤ 6 amounts to 2.6 kcal/mol, see Table S2), and for systems with n > 1, stronger bonding is observed than for ortho-benzoquinone. On the other hand, the 2,3- ones show not only a weaker bonding, with the weakest value for isomer with n = 3, but also a larger variability of ΔE BE values (19.6 kcal/mol, Table S2). A look at the deformation energy term, ΔE def, shows that the previous differences in bonding energy cannot be justified with this component, since it varies in a small range (12.2–14.4 and 12.6–15.7 kcal/mol for 1,2- and 2,3-derivatives, respectively). With the exception of benzoquinone, the trend observed for the deformation energy is somewhat expected. First, there is an increase in deformation energy with the increase in size. This is expected if one takes into account that the larger the number of rings of the system, the more deformation is accumulated (each ring is a little bit deformed and contributes to the total deformation). This trend is lost when going from n = 2 to n = 3 in 2,3-quinones, but this is again not surprising given the fact that when going from 2,3-naphthoquinone to 2,3-anthraquinone, there is a change in the electronic state and, therefore, deformation energy in 2,3-naphthoquinone is not comparable to that of 2,3-anthraquinone. Then, we must find the corresponding explanation with the interaction energy term and its particular components (Eq. 5) depicted in Fig. 7.

The similarity of the trends between ΔE BE and ΔE int allows us to conclude that this latter term is responsible for the observed ΔE BE changes. Then, the relatively constant value of ΔE int in the 1,2-derivatives is also kept for the corresponding three components ΔE Pauli, ΔV elstat, and ΔE oi that show differences of only 8.3, 2.8, and 3.7 kcal/mol, respectively (see Table S2 in the Supplementary Material). On the other hand, for the 2,3-derivatives, the observed trend of ΔE int can be mainly attributed to the ΔE oi component, since changes in both repulsive ΔE Pauli and attractive ΔV elstat terms compensate each other. It is important to notice the much larger variability of these components for 2,3-isomers, amounting to 19.6, 9.8, and particularly 24.8 kcal/mol for ΔE Pauli, ΔV elstat, and ΔE oi, respectively.

More importantly, if we now decompose ΔE oi into ΔE σ and ΔE π contributions (Fig. 8), we can definitely affirm that the different behavior observed in 1,2- and 2,3-isomers can be mainly justified through this latter π-contribution, which causes the crucial variability with the change of the number of rings and gives the trend of ΔE BE observed in Fig. 6. Although the ΔE σ component provides most of the final ΔE oi term, the observed trend is basically due to the ΔE π contribution. Next, we will try to find the reason for such different behavior of this π-component between these isomers under analysis.

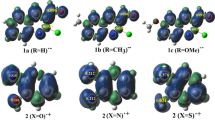

For this purpose, the overlaps 〈SOMOπ|SOMOπ〉 between the π single occupied molecular orbitals (SOMOπ) of each fragment have been calculated (Fig. 9). Let us remind that we consider each fragment at its quadruplet state, so we have two unpaired σ electrons and one unpaired electron on a π-orbital to form two σ- and one π-bonds in the final either 1,2- or 1,3-quinone derivatives. As it can be observed, the lowest overlap is found for 2,3-tetraquinone, thus justifying the above observed behavior concerning ΔE π.

The higher 〈SOMOπ|SOMOπ〉 overlaps are easily understood from the inspection of the SOMOπ shapes of the ·C4n−2H2n–CH·· and ··CH–CO–CO· fragments depicted in Fig. 10 (SOMOπ of all ·C4n−2H2n–CH·· fragments are shown in Table S3). As can be seen, the π-interaction between these two fragments is more favorable when the ·C4n−2H2n–CH·· and ··CH–CO–CO· fragments interact to yield 1,2-quinones because the largest lobes of the two SOMOπ located in the CH moieties overlap in this particular 1,2-arrangement. The difference in overlap with the two dispositions is less for n = 2 and increases for n ≥ 3, following the same trend as the calculated 〈SOMOπ|SOMOπ〉 overlaps.

Differences in shapes are also significant for σ-orbitals. The shapes of SOMOσ1 (Table S4) and SOMOσ2 (Table S5) are clearly different for 1,2- and 2,3-quinones. The corresponding orbital overlaps of these latter isomers are larger, in line with the stronger attractive σ-orbital interactions observed (see Fig. 8a). The graphical presentation of SOMOπ, SOMOσ1, and SOMOσ2 orbitals for the fragment with the C=O groups is given in Table S6, but as expected, their shapes are very similar for both quinone isomers.

Interrelations of σ- and π-electron energies for both types of derivatives are presented in Fig. 11. These relationships suggest a much more important contribution of π-electron structure as responsible for changes in σ-energy for the 2,3-quinone molecules than for 1,2-ones. Additionally, in the former case, a decrease in ΔE π is partially compensated by strengthening of σ-interactions. Moreover, it should be noted that ΔE σ describes changes of two σ-bonds, whereas ΔE π concerns only one bond. Therefore, at least for 2,3-derivatives, σ-type interactions can also be significant.

At this point, it would be worth comparing previous 1,2-naphthoquinone and 2,3-naphthoquinone isomers (Scheme 4) with phenanthrene and anthracene (Scheme 6). We can see that the two sets of isomers have a common fragment (the left one), although the other ones do not differ so much, as, in the sense that the two O atoms are changed by two HC=CH groups that are part of an aromatic six-membered ring. The corresponding EDA results for these systems (for phenanthrene and anthracene similar results were reported in Ref. [75]) are summarized in Table 1.

As in the case of quinone derivatives, 1,2-benzenoid analogue (phenanthrene) was found to be more stable than 2,3-one (anthracene). Again, we can observe that the main component which explains the stability differences in the two sets of isomers comes from the π-orbital interaction component (ΔE π), with a much higher variability in quinone derivatives than between anthracene and phenanthrene.

Finally, an important quantity related to stability of a given system is the hardness [58], η, defined by Eq. (14). Hardness is a measure of the resistance of chemical species to change its electronic configuration. As can be seen in Fig. 12, the HOMO–LUMO gaps of 1,2-systems are larger than for 2,3-ones, in line with greater stability of 1,2-derivatives (see Fig. 4) as well as the changes observed for kinked and straight phenanthrene and anthracene by some of us [75]. It is worth to note that for 1,2-quinones, the maximum is observed for 1,2-naphthoquinone, whereas in the case of 2,3-derivatives, HOMO–LUMO gap decreases monotonically with enlarging of the molecule. Dependences of HOMO and LUMO orbital energies on the number of rings for studied quinone derivatives are presented in Fig. S3. Energy of the HOMO increases (the value is less negative) in a regular way with increasing the number of rings for both isomers. LUMO energies of 1,2-quinones are higher than for 2,3-ones, according to greater stability of the former derivatives.

4 Conclusions

As a whole, 1,2-quinone derivatives of linear benzenoids are more stable than their 2,3-quinone isomers. For these latter, from 2,3-anthraquinone to longer analogues, the diradical singlet state is the ground state structure. By means of the energy decomposition analysis (EDA), we showed that the larger stability of 1,2-quinones is due to stronger bonding that comes from stronger orbital interactions, in which π-contribution plays a main role. Better π-orbital interactions are a result of a more favorable overlap between the SOMOπ of the ·C4n−2H2n–CH·· and ··CH–CO–CO· fragments in the 1,2-arrangement. Interestingly, the influence of the π-orbital interactions on the relative stability between 1,2- and 2,3-naphthaquinones is larger than that observed between phenanthrene and anthracene. In both cases, the kinked isomers are favored due to better π-interactions.

Furthermore, 1,2-quinone derivatives present a monotonic change of the different analyzed properties: either structural (C=O bond lengths), aromatic (HOMA, FLU, MCI), or energetic criteria. At difference, 2,3-quinone isomers break this monotonic trend from 2,3-naphthoquinone to 2,3-anthroquinone in all the different measures. Again, through an EDA carried out with two equivalent fragments to form any of the two isomers, we can conclude that the orbital interactions in the π-system are the responsible for such difference.

Concerning the aromaticity analysis, for both isomers, the ring containing the quinoid fragment is antiaromatic, while electronic delocalization of the remaining rings is distributed differently. For 1,2-isomers, the aromaticity of the middle ring is the highest, whereas in the case of 2,3-isomers, the most aromatic is the terminal ring. Elongation of the system causes the decrease in the aromaticity of all rings in both cases.

References

IUPAC (1997) Compendium of chemical terminology, 2nd ed

Hirst J (2010) Towards the molecular mechanism of respiratory complex I. Biochem J 425:327–339

Nowicka B, Kruk J (2010) Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797:1587–1605

Chambers JQ (1988) Electrochemistry of quinones. In: Patai S, Rappoport Z (eds) The chemistry of quinonoid compounds, Chap 12, vol 2. Wiley, New York, pp 719–757

Guin PS, Das S, Mandal PC (2008) Electrochemical reduction of sodium 1,4-dihydroxy-9,10- anthraquinone-2-sulphonate in aqueous and aqueous dimethyl formamide mixed solvent: a cyclic voltammetric study. Int J Electrochem Sci 3:1016–1028

Kruszewski J, Krygowski TM (1972) Definition of aromaticity basing on the harmonic oscillator model. Tetrahedron Lett 13:3839–3842

Krygowski TM (1993) Crystallographic studies of inter- and intramolecular interactions reflected in aromatic character of π-electron systems. J Chem Inf Comput Sci 33:70–78

Bultinck P, Rafat M, Ponec R, van Gheluwe B, Carbó-Dorca R, Popelier P (2006) Electron delocalization and aromaticity in linear polyacenes: atoms in molecules multicenter delocalization index. J Phys Chem A 110:7642–7648

Bultinck P, Ponec R, Van Damme S (2005) Multicenter bond indices as a new measure of aromaticity in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J Phys Org Chem 18:706–718

Matito E, Duran M, Solà M (2005) The aromatic fluctuation index (FLU): A new aromaticity index based on electron delocalization. J Chem Phys 122:014109 Erratum: The aromatic fluctuation index (FLU): A new aromaticity index based on electron delocalization. J Chem Phys 122:014109 (2005). (2006) íbid 125:059901

Szatyłowicz H, Krygowski TM, Palusiak M, Poater J, Solà M (2011) Routes of π-electron delocalization in 4-substituted-1,2-benzoquinones. J Org Chem 76:550–556

Aromaticity, pseudo-aromaticity, antiaromaticity. Proceedings of an International Symposium held in Jerusalem 1970. Bergmann ED, Pullman B (eds) Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, 1971

Lloyd D (1990) The chemistry of conjugated cyclic compounds: to be or not to be like benzene. Wiley, New York

Minkin VI, Glukhovtsev MN, Simkin BYA (1995) Aromaticity and antiaromaticity. Wiley, New York

Schleyer PVR (ed) (2001) Aromaticity. Chem Rev 101:1115–1566

Shahamirian M, Cyrański MK, Krygowski TM (2011) Conjugation paths in monosubstituted 1,2-and 2,3-naphthoquinones. J Phys Chem A 115:12688–12694

Ciesielski A, Krygowski TM, Cyrański MK, Dobrowolski MA, Balaban AT (2009) Are thermodynamic and kinetic stabilities correlated? A topological index of reactivity toward electrophiles used as a criterion of aromaticity of polycyclic benzenoid hydrocarbons. J Chem Inf Model 49:369–376

Delamere C, Jakins C, Lewars E (2001) Tests for aromaticity applied to the pentalenoquinones—a computational study. Can J Chem 79:1492–1504

Becke AD (1993) Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys 98:5648–5652

Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG (1988) Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B 37:785–789

Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ (1994) Ab Initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J Phys Chem 98:11623–11627

Krishnan R, Binkley JS, Seeger R, Pople JA (1980) Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J Chem Phys 72:650–654

McLean AD, Chandler GS (1980) Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z = 11–18. J Chem Phys 72:5639–5648

Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AJ, Burant C, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski JD, Fox J (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision A.1. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford

Hachmann J, Dorando JJ, Avilés M, Chan GK-L (2007) The radical character of the acenes: a density matrix renormalization group study. J Chem Phys 127:134309

Malrieu JP, Trinquier G (2012) A recipe for geometry optimization of diradicalar singlet states from broken-symmetry calculations. J Phys Chem A 116:8226–8237

Snyder GJ (2012) Rational design of high-spin biradicaloids in the isobenzofulvene and isobenzoheptafulvene series. J Phys Chem A 116:5272–5291

Chilkuri VG, Trinquier G, Amor NB, Malrieu JP, Guihéry N (2013) In search of organic compounds presenting a double exchange phenomenon. J Chem Theory Comput 9:4805–4815

Luo D, Lee S, Zheng B, Sun Z, Zeng W, Huang K-W, Furukawa K, Kim D, Webster RD, Wu J (2014) Indolo[2,3-b]carbazoles with tunable ground states: how Clar’s aromatic sextet determines the singlet biradical character. Chem Sci 5:4944–4952

Trinquier G, Malrieu JP (2015) Kekulé versus Lewis: when aromaticity prevents electron pairing and imposes polyradical character. Chem Eur J 21:814–828

Poater J, Bickelhaupt FM, Sola M (2007) Didehydrophenanthrenes: structure, singlet–triplet splitting, and aromaticity. J Phys Chem A 111:5063–5070

Fonseca Guerra C, Snijders JG, te Velde G, Baerends EJ (1998) Towards an order-N DFT method. Theor Chem Acc 99:391–403

te Velde G, Bickelhaupt FM, Baerends EJ, Guerra CF, van Gisbergen SJA, Snijders JG, Ziegler T (2001) Chemistry with ADF. J Comput Chem 22:931–967

Baerends EJ, Autschbach J, Bérces A, Berger JA, Bickelhaupt FM, Bo C, de Boeij PL, Boerrigter PM, Cavallo L, Chong DP, Deng L, Dickson RM, Ellis DE, van Faassen M, Fan L, Fischer TH, Fonseca Guerra C, van Gisbergen SJA, Groeneveld JA, Gritsenko OV, Grüning M, Harris FE, van den Hoek P, Jacob CR, Jacobsen H, Jensen L, Kadantsev ES, van Kessel G, Klooster R, Kootstra F, van Lenthe E, McCormack DA, Michalak A, Neugebauer J, Nicu VP, Osinga VP, Patchkovskii S, Philipsen PHT,Post D, Pye CC, Ravenek W, Romaniello P, Ros P, Schipper PRT, Schreckenbach G, Snijders J, Solà M, Swart M, Swerhone D, te Velde G, Vernooijs P, Versluis L, Visscher L, Visser O, Wang F, Wesolowski TA, van Wezenbeek EM, Wiesenekker G, Wolff SK, Woo TK, Yakovlev AL, Ziegler T. Scientific Computing & Modeling (SCM), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. See also: www.scm.com

Kitaura K, Morokuma K (1976) New energy decomposition scheme for molecular-interactions within Hartree–Fock approximation. Int J Quantum Chem 10:325–340

Morokuma K (1977) Why do molecules interact? The origin of electron donor–acceptor complexes, hydrogen bonding, and proton affinity. Acc Chem Res 10:294–300

Ziegler T, Rauk A (1977) On the calculation of bonding energies by the Hartree Fock Slater method—I. The transition state method. Theor Chim Acta 46:1–10

Ziegler T, Rauk A (1979) A theoretical study of the ethylene-metal bond in complexes between Cu+, Ag+, Au+, Pt0, or Pt2+ and ethylene, based on the Hartree–Fock–Slater transition-state method. Inorg Chem 18:1558–1565

Bickelhaupt FM, Baerends EJ (2000) Kohn–Sham density functional theory: predicting and understanding chemistry. Rev Comput Chem 15:1–86

von Hopffgarten M, Frenking G (2012) Energy decomposition analysis. WIREs Comput Mol Sci 2:43–62

Bickelhaupt FM, Nibbering NMM, van Wezenbeek EM, Baerends EJ (1992) Central bond in the three CN• dimers NC–CN, CN–CN, and CN–NC: electron pair bonding and Pauli repulsion effects. J Phys Chem 96:4864–4873

PvR Schleyer (2001) Aromaticity: introduction. Chem Rev 101:1115–1117

Krygowski TM, Cyrański MK (2001) Structural aspects of aromaticity. Chem Rev 101:1385–1419

Bader RFW (1990) Atoms in molecules: a quantum theory. Oxford University Press, New York

Giambiagi M, de Giambiagi MS, dos Santos CD, de Figueiredo AP (2000) Multicenter bond indices as a measure of aromaticity. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2:3381–3392

Bultinck P, Fias S, Ponec R (2006) Local aromaticity in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: electron delocalization versus magnetic indices. Chem Eur J 12:8813–8818

Mandado M, Bultinck P, González-Moa MJ, Mosquera RA (2006) Multicenter delocalization indices vs. properties of the electron density at ring critical points: a study on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem Phys Lett 433:5–9

Bultinck P (2007) Critical analysis of the local aromaticity concept in polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Faraday Discuss 135:347–365

Bultinck P, Ponec R, Carbó-Dorca R (2007) Aromaticity in linear polyacenes: generalized population analysis and molecular quantum similarity approach. J Comput Chem 28:152–160

Fias S, Fowler PW, Delgado JL, Hahn U, Bultinck P (2008) Correlation of delocalization indices and current-density maps in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem Eur J 14:3093–3099

Feixas F, Matito E, Poater J, Solà M (2008) On the performance of some aromaticity indices: a critical assessment using a test set. J Comput Chem 29:1543–1554

Matito E, Solà M (2009) The role of electronic delocalization in transition metal complexes from the electron localization function and the quantum theory of atoms in molecules viewpoints. Coord Chem Rev 253:647–665

Fias S, Van Damme S, Bultinck P (2010) Multidimensionality of delocalization indices and nucleus-independent chemical shifts in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons II: proof of further nonlocality. J Comput Chem 31:2286–2293

Feixas F, Jiménez-Halla JOC, Matito E, Poater J, Solà M (2010) A test to evaluate the performance of aromaticity descriptors in all-metal and semimetal clusters. An appraisal of electronic and magnetic indicators of aromaticity. J Chem Theory Comput 6:1118–1130

Feixas F, Matito E, Duran M, Poater J, Solà M (2011) Aromaticity and electronic delocalization in all-metal clusters with single, double, and triple aromatic character. Theor Chem Acc 128:419–431

Feixas F, Matito E, Poater J, Solà M (2013) Metalloaromaticity. WIREs Comput Mol Sci 3:105–122

Matito E (2006) In: ESI-3D: electron sharing indexes program for 3D molecular space partitioning. institute of computational chemistry and catalysis, Girona. http://iqc.udg.es/~eduard/ESI

Pearson RG (2005) Chemical hardness and density functional theory. J Chem Sci 117:369–377

Bendikov M, Duong HM, Starkey K, Houk KN, Carter EA, Wudl F (2004) Oligoacenes: theoretical prediction of open-shell singlet diradical ground states. J Am Chem Soc 126:7416–7417 (2004) Erratum: Oligoacenes: Theoretical prediction of open-shell singlet diradical ground states (Journal of the American Chemical Society (2004), ibid 126:10493 (7416–7417))

Payne MM, Parkin SR, Anthony JE (2005) Functionalized higher acenes: hexacene and heptacene. J Am Chem Soc 127:8028–8029

Poater J, Bofill JM, Alemany P, Solà M (2005) Local aromaticity of the lowest-lying singlet states of [n]acenes (n = 6–9). J Phys Chem A 109:10629–10632

Clar E (1972) The aromatic sextet. Wiley, New York

Solà M (2013) Forty years of Clar’s aromatic π-sextet rule. Front Chem 1:22

Sun Z, Zeng Z, Wu J (2013) Benzenoid polycyclic hydrocarbons with an open-shell biradical ground state. Chem Asian J 8:2894–2904

Sun Z, Lee S, Park KH, Zhu X, Zhang W, Zheng B, Hu P, Zeng Z, Das S, Li Y, Chi C, Li R-W, Huang K-W, Ding J, Kim D, Wu J (2013) Dibenzoheptazethrene isomers with different biradical characters: an exercise of Clar’s aromatic sextet rule in singlet biradicaloids. J Am Chem Soc 135:18229–18236

Su Y, Wang X, Xheng X, Zhang Z, Song Y, Sui Y, Li Y, Wang X (2014) Tuning ground states of Bis(triarylamine) Dications: from a closed-shell singlet to a diradicaloid with an excited triplet state. Angew Chem Int Ed 53:2857–2861

Shimizu A, Hirao Y, Matsumoto K, Kurata H, Kubo T, Uruichi M, Yakushi K (2012) Aromaticity and π-bond covalency: prominent intermolecular covalent bonding interaction of a Kekulé hydrocarbon with very significant singlet biradical character. Chem Commun 48:5629–5631

Matsui H, Fukuda K, Hirosaki Y, Takamuku S, Champagne B, Nakano M (2013) Theoretical study on the diradical characters and third-order nonlinear optical properties of cyclic thiazyl diradical compounds. Chem Phys Lett 585:112–116

Nobusue S, Miyoshi H, Shimizu A, Hisaki I, Fukuda K, Nakano M, Tobe Y (2015) Tetracyclopenta[def, jkl, pqr, vwx]tetraphenylene: a potential tetraradicaloid hydrocarbon. Angew Chem Int Ed 54:2090–2094

Yoneda K, Matsui H, Fukuda K, Takamuku S, Kishi R, Nakano M (2014) Open-shell characters and second hyperpolarizabilities for hexagonal graphene nanoflakes including boron nitride domains. Chem Phys Lett 595–596:220–225

Shimizu A, Hirao Y, Kubo T, Nakano M, Botek E, Champagne B (2012) Theoretical consideration of singlet open-shell character of polyperiacenes using Clar’s aromatic sextet valence bond model and quantum chemical calculations. AIP Conf Proc 1504:399–405

Hoffmann R (1983) Foreword to: determination of the geometrical structure of free molecules. Vilkov IV, Mastryukov VS, Sadova NI (eds) Mir Publishers, Moscow

Krygowski TM (1972) Towards the unification of the substituent (position) constants in Hammett–Streitwieser equation. Tetrahedron 28:4981–4987

Baker R, Eaborn C, Taylor R (1972) Aromatic reactivity. Part L. Thiophen, benzo[b]thiophen, anisole, and thioanisole in detritiation. Substituent constants for use in electrophilic aromatic substitution. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2:97–101

Poater J, Visser R, Solà M, Bickelhaupt FM (2007) Polycyclic benzenoids: Why kinked is more stable than straight. J Org Chem 72:1134–1142

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the European Union in the framework of European Social Fund through the Warsaw University of Technology Development Programme. O.A. S., H. S. and T.M. K. gratefully acknowledge the Foundation for Polish Science for supporting this work under MPD/2010/4 project “Towards Advanced Functional Materials and Novel Devices—Joint UW and WUT International PhD Programme” and the Interdisciplinary Center for Mathematical and Computational Modeling (Warsaw, Poland) for providing computer time and facilities. Thanks are also to the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (Projects CTQ2011-23156/BQU and CTQ2011-25086) and the Generalitat de Catalunya (project numbers 2014SGR931, Xarxa de Referència en Química Teòrica i Computacional, and ICREA Academia 2014 prize for MS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Published as part of the special collection of articles derived from the XI Girona Seminar and focused on carbon, metal, and carbon–metal clusters.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Szatylowicz, H., Krygowski, T.M., Solà, M. et al. Why 1,2-quinone derivatives are more stable than their 2,3-analogues?. Theor Chem Acc 134, 35 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-015-1635-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-015-1635-5