Abstract

Rationale

Psychosis susceptibility is mediated in part by the dopaminergic neurotransmitter system. In humans, individual differences in vulnerability for psychosis are reflected in differential sensitivity for psychostimulants such as amphetamine. We hypothesize that the same genes and pathways underlying behavioral sensitization in mice are also involved in the vulnerability to psychosis.

Objectives

The aim of the current study was to investigate which genes and pathways may contribute to behavioral sensitization in different dopaminergic output areas in the mouse brain.

Methods

We took advantage of the naturally occurring difference in psychostimulant sensitivity in DBA/2 mice and selected animals displaying extremes in behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Subsequently, the dopamine output areas, prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) area of the hippocampus, were isolated by laser microdissection and subjected to DNA microarray analysis 1 h after a challenge dose of amphetamine.

Results

A large number of genes with differential expression between high and low responders were identified, with no overlap between brain regions. Validation of these gene expression changes with real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction demonstrated that the most robust and reproducible effects on gene expression were in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Interestingly, many of the validated genes in CA1 are members of the cAMP response element (CRE) family and targets of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and myocyte enhancer factor 2 (Mef2) transcription factors.

Conclusion

We hypothesize that CRE, Mef2, and GR signaling form a transcription regulating network, which underlies differential amphetamine sensitivity, and therefore, may play an important role in susceptibility to psychosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychosis is characterized by a gradual loss of contact with reality, progressing from emotional instability, acoustic and visual disturbances, and decreased discriminative ability for real and surreal ideas and memories to more pronounced symptoms like hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorders. Psychotic-like symptoms can be induced by psychostimulant drugs like amphetamine (Janowsky and Risch 1979). Patients with a high susceptibility for psychosis, such as schizophrenia patients, display an increased sensitivity to amphetamine (Strakowski et al. 1997) that resembles the behavioral sensitization found in rodents after repeated exposure to amphetamine (Alessi et al. 2003; Peleg-Raibstein et al. 2006, 2008; Tenn et al. 2003). This behavioral sensitization is characterized by a progressive and persisting increase in the behavioral activity and neurochemical responses to psychostimulants, such as stimulation of locomotor activity, stereotypy, and dopamine (DA) release in the striatum (Featherstone et al. 2007; Laruelle and Abi-Dargham 1999; Morrens et al. 2006). Moreover, the number of DA D2 receptors in the high-affinity conformational state is altered in the striatum, whereas the total expression of DA D2 receptors is not changed in both sensitized animals and schizophrenia patients (Seeman et al. 2005, 2007). Substantial interindividual differences exist in susceptibility to develop psychosis as well as in sensitivity to amphetamine (Alessi et al. 2003). It has been hypothesized that individuals that are more sensitive to amphetamine are also more susceptible to become psychotic (Post 1992; Segal et al. 1981). Based on these similarities, the amphetamine sensitization model can be considered a promising animal model to study several aspects of schizophrenia (Featherstone et al. 2007).

Persistent neuroplastic alterations in the reward circuitry, in particular in the mesolimbic DA pathway, are associated with the expression of behavioral sensitization (Nestler 2005a). The mesolimbic DA pathway originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projects to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), and other forebrain regions including the cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) subregion of the hippocampus (Floresco et al. 2001; Gasbarri et al. 1994; Thierry et al. 2000). Induction and expression of behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants is a complex process in which various neurotransmitters, in particular DA and glutamate, result in downstream molecular adaptations in the VTA–NAc circuitry and other limbic brain regions. In the VTA, enhanced glutamatergic neurotransmission results in a sensitized state resembling long-term potentiation. In the NAc, induction of the transcription factors ΔFosB and cAMP response element binding (CREB) appear to be common adaptations in response to chronic exposure to drugs of abuse, contributing to the sensitized state (McClung and Nestler 2003; McClung et al. 2004; Nestler 2005b; Shaw-Lutchman et al. 2003). In addition, the ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) pathway and cAMP-independent activation of protein kinase B (Akt)-GSK-3 (glycogen synthase kinase 3) signaling may also play a role in long-lasting behavioral sensitization (Beaulieu et al. 2007; Emamian et al. 2004; Valjent et al. 2006). However, still a lot remains unresolved regarding the molecular events that contribute to behavioral sensitization in different brain regions of the mesolimbic DA circuitry.

The aim of the current study was to investigate which genes and pathways may contribute to behavioral sensitization in different parts of the mesolimbic circuitry in the mouse brain. We hypothesize that the same genes and pathways underlying behavioral sensitization are also involved in the vulnerability to psychosis. To investigate these molecular pathways, we took advantage of the naturally occurring variability in behavioral sensitization to amphetamine in DBA/2 mice, an inbred mouse line (de Jong et al. 2007), thus ruling out the influence of genetic differences. We developed a sensitization regimen that allowed us to separate mice in two distinct groups showing very high sensitization and no sensitization to amphetamine, respectively, despite the exact same amphetamine treatment. Large-scale gene expression profiles were generated of several dopaminergic output brain regions, including the CA1 region of the hippocampus, the NAc, and PFC in mice selected for extremes in behavioral sensitization to amphetamine, in search of susceptibility genes and pathways underlying the differential behavioral sensitization.

Materials and methods

Drugs

d-Amphetamine ((+)-α-methylphenethylamine sulfate; Unikem A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride. Doses are listed as salt equivalents (in milligrams per kilogram).

Animals

Animal experiments were in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Danish Animal Experimentation Inspectorate. DBA/2 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Salzfeld, Germany) were housed four mice per cage in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment at a 12-h light–dark cycle. During the experiment, animals had ad libitum access to water and food. Mice were left undisturbed for 14 days prior to initiation of the experiments.

Amphetamine sensitization

In experiment 1, mice were divided into four groups based on the treatment received during days 1–5 and on day 20, respectively: group 1 (amph/amph, n = 100), group 2 (sal/sal, n = 10), group 3 (sal/amph, n = 10), and group 4 (amph/sal, n = 10). Animals received either d-amphetamine (2.5 mg/kg) or saline for five consecutive days (days 1–5). After a 14-day withdrawal period, animals were given a low-dose amphetamine challenge (1.25 mg/kg) or saline (day 20) (for a detailed scheme, see Fig. 1). At the drug challenge (day 20), locomotor behavior was assessed as described below. Based on the locomotor response to the amphetamine challenge on day 20, the 10% amph/amph animals with the highest locomotor response were designated high responders (HR; n = 10), while the 10% animals with the lowest response were designated low responders (LR; n = 10). The HR and LR were used for subsequent gene expression analysis.

a Animals received either d-amphetamine (2.5 mg/kg) or saline for five consecutive days (days 1–5). After a 14-day withdrawal period (day 20), animals were given a low-dose amphetamine challenge (1.25 mg/kg) or saline and the 10% population extremes in the amph/amph group (LR and HR) were selected. In the expression profiling study, mice were sacrificed 1 h after the challenge on day 20 (experiment 1). b In the follow-up study (experiment 2), the LR and HR received an additional amphetamine (1.25 mg/kg) challenge on day 27 and were sacrificed 1 h later. Locomotor tests were performed on the indicated days

In a follow-up experiment (experiment 2), it was investigated whether the HR and LR phenotype is stable. A new batch of animals was subjected to the same treatment and dosing regimen as in the first study. The selected 10% HR and LR of the amph/amph group (n = 10 each) on day 20 were subsequently left undisturbed for an additional 7 days and rechallenged with 1.25 mg/kg on day 27 and locomotor behavior was measured again (Fig. 1). The HR and LR were used for revalidation of gene expression changes measured in experiment 1.

Locomotor behavior

Animals were placed individually in Makrolon locomotor activity cages (20 × 35 × 18 cm; Lundbeck). Following a 60-min habituation period, amphetamine or vehicle was administered and locomotor activity was recorded for an additional 60 min. The locomotor activity cages were equipped with 5 × 8 infrared light sources plus photocells. The light beams crossed the cage 1.8 cm above the bottom of the cage. During the test session, locomotor activity was recorded as crossings of infrared light beams, and total locomotor count represents the accumulated number of crossings over the 60-min period. The recording of a motility count required interruption of two adjacent light beams, thus avoiding counts induced by stationary movements of the mice. All experiments were conducted during the light phase of the cycle and initiated using a clean cage.

Tissue dissection

Selected mice were sacrificed directly after the locomotor activity measurement on day 20 (experiment 1) and on day 27 (follow-up experiment 2). Brains were rapidly dissected and snap frozen in isopentane (cooled in ethanol placed on pulverized dry ice) and stored at −80°C for later use.

Brain amphetamine levels

Amphetamine in total brain homogenates was measured in two groups (n = 10 each) of mice with locomotor activity counts just below the highest and just above the lowest responders. Amphetamine levels were measured by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) to test whether differences in responsiveness could be accounted for by differences in brain drug exposure. Brain tissue was homogenated with four times its weight of acetonitrile/water (70:30) using a Tomtec Autogizer. The supernatant was analyzed like plasma. Online sample preparation and LC were performed with turbulent flow chromatography (Cohesive Technologies, UK), using a dual-column configuration. MS/MS detection was done with an Applied Biosystems Sciex API 3000 instrument in positive ion electrospray ionization mode.

Laser microdissection

Laser microdissection (LMD) was performed as previously described (Datson et al. 2004) on brain tissue from experiment 1. Briefly, coronal brain sections (8 μm) were cut using a cryostat at −18°C. According to the Mouse Brain Atlas (Franklin and Paxinos 1997), cryosections from CA1 area were collected starting at bregma −1.58, NAc cryosections between bregma +1.70 and +1.18, and PFC cryosections (prelimbic and infralimbic cortex) between bregma +2.80 and +2.10. Both hemispheres were used for sectioning. Cryosections were thaw mounted on PEN membrane slides (1440-1000, PALM, Bernried, Germany) which had been pretreated by heating for 4 h at 180°C and subsequent UV irradiation for 30 min at 254 nm. After sectioning, the slices were kept at −80°C until further use. On the day of LMD, the slides were briefly stained with hematoxylin (10%), dehydrated in 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol, briefly dipped in xylene, and dried at 40°C. Immediately afterwards, the slides were used for LMD on a PALM MicroLaser System (PALM, Bernried, Germany) and the laser microdissected tissue fragments were collected in adhesive caps (1440-0250 PALM, Bernried, Germany). A conservative estimate of CA1 was taken to avoid contamination with CA2/CA3. For NAc, an area containing both the core and shell was dissected. For PFC, both prelimbic and medial orbital cortical regions were combined (Fig. 2). Per mouse, a total of four sections were dissected and pooled to constitute a sample for subsequent linear amplification and microarray hybridization.

Scheme showing the connection between the selected brain areas including examples of LMD (indicated by thick arrows). PFC prefrontal cortex, IL infralimbic, PL prelimbic, NAc nucleus accumbens, CA1 cornu ammonis 1 region of the hippocampus, VTA ventral tegmental area, Glu glutamate, DA dopamine, GABA gamma-aminobutyric acid. Red arrows indicate glutamatergic neurons, black arrows indicate dopaminergic neurons, and blue arrows indicate GABAergic neurons (Adapted from Thierry et. al., 2000)

RNA isolation, linear amplification, and microarray hybridization

Immediately after LMD, RNA was isolated using Trizol (15596-026, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Linear acrylamide was added as a carrier. RNA quality and quantity were checked by analyzing 1 μl of RNA on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Pico LabChip Kit (5065-4473, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, USA). Ten nanograms of total RNA was used for the first round of linear amplification using the GeneChip One-Cycle Target Labeling and Control Reagents (P/N 900493, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For the second round of amplification, 100 ng of input RNA was used, during which the RNA was biotin-labeled using the GeneChip Two-Cycle Target Labeling and Control Reagents (P/N 900494, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

GeneChip hybridization

Twenty micrograms of biotinylated RNA was subsequently fragmented using RNA Fragmentation Reagents (No. AM8740, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The biotinylated and fragmented RNA was hybridized to GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix), containing approximately 45,000 probe sets representing 39,000 transcripts and 35,000 different genes. Hybridizations were conducted at the Leiden Genome Technology Center (LGTC, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, USA). A total of 60 microarrays were hybridized, per brain region 10 HR and 10 LR.

Data analysis

Raw images were analyzed and features extracted using Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software (Affymetrix, Foster City, CA, USA). For each brain region, the resulting CEL files containing probe-level information were then normalized and converted to gene intensity values by the GC-RMA algorithm within BRB Arraytools version 3.7.3 developed by Dr. Richard Simon and the BRB Array Development Team (Simon et al. 2007). To identify differentially expressed genes, we applied a two-sample t test (fold change > 1.2 and p value cutoff of p < 0.01) comparison between HR and LR. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity® Systems, http://www.ingenuity.com) version 7.5 was used to identify pathways, networks, and for gene list matching to published datasets of genes involved in specific transcription regulation systems (Mef2, cAMP response element [CRE], and GR). The gene lists for the specific transcription regulation systems were retrieved from the supplementary material in the relevant publications (Pfenning et al. 2007; Wu and Xie 2006; Zhang et al. 2005) and loaded into Ingenuity as comparison datasets.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Primers for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) validation were designed using Primer3 freeware within the target sequence used by Affymetrix for probe design. Primers were checked for specificity using BLAST (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA) and for hairpins and self-complementarity using oligo 4.0 (MBI, Cascade, CO, USA). The primer sequences of the validated genes that were measured can be found in Supplementary Table SI. RT-qPCR measurements were performed on amplified RNA from experiment 1 to replicate the results from the GeneChip analysis. cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScriptTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (170-8897, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-qPCR was performed on a Lightcycler 2.0 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland) using the Lightcycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I Kit (Roche). The standard curve method was used to quantify the expression differences (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to assess significant differential gene expression between LR and HR.

Brain tissue from follow-up experiment 2 was used to replicate the changes in gene expression between LR and HR found in the CA1 area in an independent experiment. For this purpose, the dorsal hippocampus was dissected from frozen brain and eight punches containing CA1 tissue were obtained from two 1-mm tissue sections. RNA was synthesized to cDNA without further amplification and RT-qPCR and data analysis were performed as previously reported (Christensen et al. 2010) on a selection of genes that were successfully validated in experiment 1.

Results

DBA/2 mice display large and stable individual differences in sensitization to amphetamine

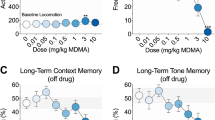

The locomotor responses to the challenge dose of amphetamine (1.25 mg/kg) or saline on day 20 are depicted in Fig. 3a. On average, animals that received amphetamine pretreatment on days 1–5 (amph/amph) were more responsive to the acute amphetamine challenge than saline pretreated mice (sal/amph), signifying the occurrence of sensitization. However, a large interindividual variability was observed in the amph/amph group. The 10% amph/amph animals with highest locomotor response to amphetamine on day 20 were designated HR (n = 10), while the 10% animals with the lowest response were designated LR (n = 10). In an independent follow-up study, it was demonstrated that the HR and LR phenotypes are stable until at least 1 week after the first drug challenge (Fig. 3b). The slight increase in both groups might signify further incubation of sensitization which is known to occur with prolonged withdrawal periods.

a Locomotor responses to the amphetamine (1.25 mg/kg) or saline challenge on day 20. Data are represented as total activity count over the 60-min treatment period. sal/sal n = 10, sal/amph n = 10, amph/sal n = 10, amph/amph n = 100. Circles indicate the 10% population extremes (LR, n = 10; HR, n = 10) in the amph/amph group selected for gene expression profiling. b Locomotor responses of the 10% population extremes in the amph/amph group (selected on day 20) to the amphetamine (1.25 mg/kg) challenges on days 20 and 27. Data are represented as total activity count over the 60-min treatment period. LR, n = 10; HR, n = 10. ***p < 0.001 vs LR (Mann–Whitney rank sum test)

Amphetamine exposure is not different in HR and LR

Amphetamine in total brain homogenates was measured in two groups (n = 10 each) of mice with locomotor activity counts just below the highest (21,289 ± 377 counts) and just above the lowest responders (4,387 ± 406 counts). There was no correlation between exposure and locomotor activity (Supplementary data, Figure SI), indicating that the phenotypic difference in locomotor sensitization could not be attributed to differences in CNS amphetamine exposure.

Identification of differentially expressed genes reveals region-specific molecular signatures

To identify potential molecular changes induced by the behavioral sensitization, microarray analysis was performed on PFC, NAc, and hippocampal CA1 regions collected from 10 HR and 10 LR animals 1 h after a challenge dose of amphetamine on day 20 (Fig. 1). This time point was selected in order to examine the early factors behind the long-term changes induced by the challenge stimulus and, more importantly, to look under challenged conditions in which the differences between HR and LR are most evident. Differentially regulated genes were identified by statistically comparing GC-RMA (GeneChip Robust Multi-array Average) mean normalized values of HR to LR. Of the 45,000 probe sets on the Affymetrix GeneChip mouse genome 430 2.0 arrays, we identified 63 (39 up, 24 down), 29 (20 up, 9 down), and 105 (76 up, 29 down) genes that significantly differed in expression between HR and LR in CA1, NAc, and PFC, respectively by two-sample t test (p < 0.01, fold change > 1.2; Fig. 4a). These gene lists are referred to as the primary lists (Supplementary material, Table SII). Comparison of the three primary lists revealed no overlapping genes (Fig. 4b). Moreover, pairwise correlation analysis of all expression values in the 60 samples showed a clear distinction in region-specific expression signatures (Fig. 4c). These specific molecular signatures of the analyzed brain regions most likely reflect both their specific connectivity and function in a complex circuit as well as their distinct molecular response to amphetamine challenge.

a Volcano plots of −log10 (p value) vs. log2 (fold change). Labeled are largest fold change and lowest value genes. The blue points in each graph indicate the Affymetrix probe sets that passed the t test p < 0.01 and fold change > 1.2 statistical requirements. b Venn diagram of genes differentially expressed between HR and LR. Genes meeting the fold change > 1.2, p < 0.01 criteria were included. No common genes were identified when comparing CA1, PFC, and NAc. c Correlation matrix of expression levels between all 60 samples in the experiment. Differential expression between tissues was clearly identified. Correlation analysis was not able to differentiate between HR and LR groups

Differential expression between HR and LR was most robust in the hippocampal CA1 region

A total of 83 genes were selected for reconfirmation by RT-qPCR from all three brain regions based on overall lowest p value and highest fold change. In both NAc and PFC, the reconfirmation rates were rather low, with a reconfirmation rate of 3 out of 24 genes (12.5%) in the NAc and 5 out of 30 genes (16.7%) in the PFC. In the CA1, the reconfirmation rate was considerably higher, with a success rate of 14 out of 28 genes (50.0%).

Gene expression changes in CA1 could be replicated in a novel independent study.

The expression of several genes that were confirmed to show differential expression in the CA1 area with RT-qPCR in the first experiment was validated in an independent sensitization experiment. Gene expression of six selected genes (Arc, Nr4a1, Dusp1, Fos, Egr2, and Tiparp) was quantified in the CA1 of the phenotypically stable animals that received a second amphetamine challenge (Fig. 1). In contrast to the validation described above, the six genes were measured in non-amplified mRNA derived from manually dissected CA1 rather than LMD. Despite these technical differences, the results replicated the differential expression between LR and HR that was shown in the first study, although Nr4a1 did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5).

Validated genes overlap with several gene classes, including GR-, Mef2-, and CRE-regulated genes

The genes differentially expressed in CA1 were subjected to IPA. Genes regulated by specific transcription factors or promoter systems as identified by ChIP/ChIP technology were identified from the literature and used to compose gene lists for target genes of transcription factors Mef2, CREB, GR, and REST (repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor) (see Supplementary material, Table SIII for details). Each of the gene lists were compared to the 63 genes identified in CA1 and to a list of 2,000 randomly selected genes from the entire list of probe sets (∼45,000 probe sets). This comparison indicated a clear overrepresentation of GR, CRE, and Mef2 promoter-regulated genes among the differentially regulated gene set in CA1 (Fig. 6). The comparison was repeated with a large number of randomizations of the R2K set and the differences shown in Fig. 6 were found to be stable.

Comparison of genes regulated in CA1, NAc, and PFC to genes involved in specific transcriptional regulation as identified by ChIP/ChIP experiments. For each of the brain areas, the comparison was made for the genes identified in expression array and for those confirmed by qPCR. The R2K dataset represents 10 × 2,000 random probe sets, indicating background signal and size difference of ChIP/ChIP datasets used. Genes compared are those listed in Supplementary Table SI and shown in Fig. 4. (Supplementary Table SIII)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to elucidate which genes and pathways underlie the differences in behavioral response to amphetamine in genetically identical mice selected for responsiveness to amphetamine sensitization. The amphetamine sensitization model is suggested to reflect the heightened sensitivity of schizophrenia patients to psychostimulants and is accepted as a model for the positive symptoms observed in schizophrenia (Featherstone et al. 2007; Hermens et al. 2009; Peleg-Raibstein et al. 2008, 2009; Tenn et al. 2003). Additionally, there is increasing evidence for long-lasting cognitive deficits in sensitized animals (Featherstone et al. 2007). In this study, we used a unique setup based on genetically identical inbred mice, all receiving the same treatment yet still displaying differences in amphetamine sensitization. This is an important divergence to most studies reporting on gene expression focusing on differences in outbred strains and/or differences in treatment (e.g., control vs. amphetamine or acute vs. chronic amphetamine) (Funada et al. 2004; Palmer et al. 2005; Shilling et al. 2006; Sokolov et al. 2003). By taking this approach, we are ruling out changes in gene regulation due to variation in genetic makeup and different treatment paradigms. Thus, the differential gene regulation found in the present study most likely reflects the underlying mechanism for sensitization and may point to why some individuals get schizophrenia whereas others do not.

The largest effect of sensitization on gene expression was found in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. We observed a considerable variation in sensitization to amphetamine in DBA/2 mice measured by locomotor output. Gene expression in CA1, NAc, and PFC, all dopaminergic output brain areas, of the 10 lowest and 10 highest responders (LR and HR) was assessed 1 h after amphetamine challenge. Gene expression signatures were highly brain region-specific, which is not surprising given that these brain regions differ so extensively in basal molecular makeup. We found the strongest differential expression between LR and HR in the CA1 subregion of the hippocampus. These findings are of interest since most research on amphetamine-induced gene expression so far has focused on PFC, striatum, NAc, and VTA (Mirnics et al. 2000; Palmer et al. 2005; Yuferov et al. 2005) and not considered CA1 to play a key role in psychostimulant effects. However, our data are consistent with recent literature pointing to a prominent role of the hippocampus and DA in schizophrenia (Grace 2010; Lisman and Grace 2005; Lodge and Grace 2007, 2008; Rossato et al. 2009; for review, see Shohamy and Adcock 2010). In schizophrenic patients and high-risk individuals, there is elevated regional cerebral blood volume (rCVB) in the CA1 subregion of the hippocampus, which correlates with positive symptoms and predicts clinical progression (Gaisler-Salomon et al. 2009b; Schobel et al. 2009). The increased hippocampal activity linked to psychotic symptoms is in line with data by Grace et al. (2007) showing how the hippocampus controls DA neuron activity, possibly by increasing the number of DA neurons that can be activated by salient signals. In contrast, antipsychotic phenotype measured as reduced amphetamine-induced locomotion and release of DA in the NAc is seen in an animal model with reduced glutaminase activity, leading to a CA1/subiculum-specific decrease in rCVB (Gaisler-Salomon et al. 2009a).

Furthermore, preventing synaptic transmission in the dorsal region of the hippocampus by local infusion of the anesthetic lidocaine is able to block the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine (Degoulet et al. 2008). Finally, Crombag et al. showed that amphetamine self-administration leads to increased spine density in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Goeman et al. 2004). Although not investigated in the current study, changes in spine morphology may likely be present in our sensitized mice. The differences in expression of Mef2 target genes we identified fit well with a potential difference in spine density, given that Mef2 is a key regulator of neuronal plasticity and that manipulating Mef2 expression and activity directly influences psychostimulant sensitization (Pulipparacharuvil et al. 2008).

Since we only looked at NAc, PFC, and CA1 in the current study, we cannot exclude that gene expression differences in other dopaminergic brain regions may have contributed to the development of behavioral sensitization, e.g. the VTA or the amygdala (Yuferov et al. 2005). However, that would need to be addressed in a follow-up study.

Immediate early genes

Many of the validated genes are immediate early genes (IEGs), which are among the first genes to be expressed (hence the name) in a changing environment. Examples of IEGs identified in this study are c-fos, Dusp1, Nr4a1, Egr2, Arc, and Tiparp. Several other studies have also found IEGs to be responsive to amphetamine in the brain. Most studies show an upregulation of IEGs in the striatum in response to acute amphetamine, while chronic administration has been shown to blunt the effects of a single dose (for review, see McCoy et al. 2011). In contrast, Shilling et al. (2006) showed a downregulation of several IEGs in the PFC of HR 24 h after a single injection of methamphetamine. Downregulation of IEGs at such a late time point may represent an adaptive response to counterbalance the earlier increase in IEG expression as observed in the present study. One of the IEGs we found to be upregulated in the HR is c-fos. Interestingly, Zhang et al. (2006) found that c-fos downregulation in DA D1 receptor-containing neurons attenuates cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization. This might indicate that higher c-fos expression in the HR is a cause rather than a consequence of the observed increased locomotor response to amphetamine. In line with our findings for c-fos, two independent studies show that methamphetamine increases expression of IEG Arc from 1 h onwards in multiple brain regions, which can be blocked by giving a DA D1 receptor antagonist (Kodama et al. 1998; Yamagata et al. 2000). Since many IEGs are regulated by multiple transcription factors, the question rises what the link is to the underlying mechanisms of amphetamine sensitivity.

GR, Mef2, and Creb are important regulators of sensitization. We found a clear overrepresentation of GR, Mef2, and CRE promoter-regulated genes among the differentially regulated gene set in CA1 (Fig. 6). These transcription factors are interesting candidates linking the regulation of IEGs to mechanisms of behavioral sensitization and psychosis susceptibility.

Glucocorticoids

GR, an important receptor for glucocorticoid stress hormones in the brain, is a transcription factor that is able to regulate many of the IEGs as well as some of the other validated genes that were differentially expressed between HR and LR in CA1. Stress and more particular glucocorticoids are factors influencing sensitization to psychostimulants (Antelman et al. 1980). We have previously shown that cocaine sensitization in DBA/2 mice relies in part on corticosterone (de Jong et al. 2007). Moreover, it was shown that antagonizing GR attenuates the expression of amphetamine-induced sensitization (De Vries et al. 1996). Also, in humans, many studies have shown that psychostimulant abuse and stressful life events are associated with later-life psychotic episodes, with odds ratios even increasing with cumulative traumas (Johns et al. 2004; Shevlin et al. 2008; Wiles et al. 2006).

In rodents, a similar link between stress, glucocorticoids, and behavioral sensitization was found. Chronic social stress increased amphetamine-induced locomotion (Mathews et al. 2008) and vice versa (Antelman et al. 1980; Myin-Germeys and van Os 2007; Vanderschuren et al. 1999). Withdrawal from amphetamine leads to increased corticosterone levels in rats that show sensitization but not in nonsensitized animals (Scholl et al. 2009). DBA/2 mice are known for their vulnerability to stressful events (Weaver et al. 2004). Our findings indicate that several of the genes that are differentially expressed between LR and HR are involved in glucocorticoid signaling. For example, Nr4a1 was one of the IEGs we identified to have a higher expression in the CA1 of HR. Nr4al belongs to the family of orphan nuclear receptors and is also increased by amphetamine in the striatum (Levesque and Rouillard 2007). Nr4a1 is known to bind to NGFI-B sites in addition to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs). It has been shown that Nr4a1 can compete with the GR for binding to a negative GRE sequence on the POMC (Pro-opiomelanocortin) promoter in the hypothalamus, preventing the GR-induced inhibition of ACTH (Adrenocorticotropic hormone) (Okabe et al. 1998; Philips et al. 1997), which is part of the negative feedback of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and vital for proper functioning of the stress system. Several others of the differentially expressed genes we identified are glucocorticoid responsive, such as Dusp1 (King et al. 2009). Hippocampal Dusp1 expression is known to be induced by glucocorticoids (Morsink et al. 2006), suggesting that HR have an increased corticosterone response to the amphetamine challenge, corresponding to a sensitized HPA axis.

Mef2

The transcription factor Mef2 plays a role in regulation of IEGs and behavioral sensitization. Mef2 is a key regulator of structural synapse plasticity and has recently been implicated in behavioral sensitization to cocaine (Flavell et al. 2008; Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Chronic cocaine treatment was shown to affect Mef2 phosphorylation in the NAc, thus altering its activity (Pulipparacharuvil et al. 2008). Mef2 is phosphorylated and consequently inhibited by Cdk5 in combination with its activators p35 and p25 (Gong et al. 2003). p25 protein level, responsible for a prolonged activation of Cdk5, was shown to be increased 4 h after acute or chronic amphetamine treatment (Mlewski et al. 2008) and might explain the altered activity of Mef2 during psychostimulant sensitization. Expression of Cdk5 itself can be directly regulated by ΔFosB (Kumar et al. 2005) that in turn is increased after psychostimulant treatment and can remain elevated for weeks (Nestler 2005b). Cdk5 not only phosphorylates Mef2 but was also found to phosphorylate GR in a dexamethasone-dependent manner (Kino et al. 2007). Consequently, amphetamine-induced changes in Cdk5 may affect both GR and Mef2 transcriptional activity. This suggests that the glucocorticoid stress system and Mef2-driven pathways converge and would provide an explanation for how individual differences in stress can affect the sensitization process. Interestingly, Mef2 expression itself was not found to be different between LR and HR.

cAMP response element binding

We found that CRE family transcription factors overall can affect at least 15% of qPCR confirmed AMPH-regulated genes in CA1 (Fig. 6). In a random set of genes picked from the gene expression chip, this number is low (3.4%, see Fig. 6). This CRE family transcription factor overrepresentation is in line with the literature. The CREB protein is a transcription factor that binds to CRE DNA signature sequences and, thereby, increases or decreases the transcription of downstream genes (Purves et al. 2008). Genes relevant for amphetamine sensitization and DA function whose transcription is regulated by CREB include c-fos, BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), tyrosine hydroxylase, and many neuropeptides (such as somatostatin, enkephalin, VGF, and corticotropin-releasing hormone) (Purves et al. 2008). CREB has a well-documented role in neuronal plasticity and long-term memory formation in the brain (Silva et al. 1998). Altered cAMP signaling was previously identified to be one of the most consistent changes in the striatum in an extensive study using three genetic and one pharmacological mouse models of psychostimulant or DA supersensitivity (Yao et al. 2004). The molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying plasticity related to behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants and learning and memory may be similar (Yao et al. 2004). This fits well with our observations that CREB and GR, both known to be important for learning and memory, may be key transcription factors regulating behavioral sensitization to amphetamine.

Environmental factors

Since all mice from this inbred strain received an identical treatment, a plausible underlying cause for difference in sensitization may be that differences in handling, social hierarchy, or maternal care underlie the differential expression of amphetamine sensitivity via effects on the glucocorticoid stress system (Badiani et al. 1992; Holmes et al. 2005; Lockwood and Turney 1981). This fits well with the numerous studies pointing to an association between early childhood trauma, parental care, and social adversity and the later development of psychotic illness (Janssen et al. 2004; Morgan and Fisher 2007; Morris et al. 2006; Wicks et al. 2005). The stress system may be an important biological mechanism linking sensitization processes initiated by developmental stress exposures to an increased risk for psychosis. Recent studies have shown changes in cortisol secretion associated with smaller left hippocampal volume in first-episode psychosis patients (Mondelli et al. 2010b) and a blunted cortisol awakening response compared with controls (Mondelli et al. 2010a) and increased emotional reactivity to stress in daily life (Lataster et al. 2009).

Technical considerations

In the current study, we demonstrated that there are individual differences in gene expression in key dopaminergic output areas in the brain that reflect a differential sensitivity to amphetamine. Differences in gene expression in all three brain regions were subtle, with the majority of gene expression changes being below 1.5-fold. These modest changes in gene expression are not surprising, given that LR and HR have the same genetic background and received an identical sensitization protocol using exactly the same amphetamine dosing regimen. Nonetheless, our setup using LMD in combination with DNA microarrays is evidently sensitive enough to detect these changes. Validation of the identified gene expression changes proved to be difficult, in particular in the NAc and PFC. Validation of subtle differences in gene expression by other methods such as RT-qPCR is notoriously difficult due to limitations in sensitivity. Most commonly, a twofold change is reported as the cutoff below which microarray and qPCR data begin to lose correlation. Dallas et al. (2005) reported decreased correlations for genes expressing <1.5-fold change using qPCR and oligonucleotide microarrays. Nonetheless, we were able to validate 22 out of 87 genes with RT-qPCR, with the highest success rate (50%) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Detection of false positives may also have contributed to the relatively low success rate of validation. Using a microarray with 45,000 probe sets, a p value of 0.01 is likely to yield 450 false positives.

While comparing gene expression differences between LR and HR with the same genetic background and an identical sensitization protocol is the strength of the current study, a limitation is that we did not perform gene expression measurements in response to amphetamine challenge in the nonsensitized saline group as a reference.

Sources of experimental uncertainty

We have a high level of confidence in our CA1 array data for the following reasons. First, the genes identified here are based on strong statistical comparisons with ten biological replicates in each group, decreasing the probability of false negatives. This is in contrast to a majority of published reports where either small numbers of animals are used in each comparison group or technical replicates of pooled animals are applied to identify target genes (Pawitan et al. 2005). Second, rather than using a whole hippocampus homogenate, we specifically isolated the CA1 pyramidal cell layer, resulting in a more homogeneous population of neurons highly enriched for CA1 pyramidal neurons and, therefore, more likely to yield a transcriptional response that is undiluted by effects in other parts of the hippocampus, non-neuronal cells such as glia and isolation artefacts. We have previously demonstrated that the different subregions of the hippocampus differ profoundly in basal transcriptome, demonstrating that the brain-specific isolation and analysis of homogeneous neuronal subpopulations is of utmost importance (Datson et al. 2004; Datson et al. 2009). Third, the validation rate was high considering the small differences in expression. Finally, RT-qPCR remeasurement of representative genes in an independently performed follow-up experiment demonstrated that the changes in gene expression in CA1 were reliably reproduced and correlated with the HR or LR phenotype.

Timing

The time at which the gene expression changes were measured in the current study, i.e. 1 h after an amphetamine challenge, is a point of consideration. Our rationale for choosing this time point was that we wanted to investigate gene expression between LR and HR under challenged rather than baseline conditions, which we hypothesize is a prerequisite to identify pathways relevant for behavioral sensitization and thus susceptibility for psychosis. Under challenged conditions, the phenotypic extremes between LR and HR become evident, while under basal conditions there are no apparent differences. Furthermore, the current design is appropriate for detecting primary gene responses rather than secondary or even more downstream waves of gene expression. It could be argued that looking at a later time point would give more insight in the long-lasting changes in gene expression rather than in acute changes associated with the amphetamine challenge. Indeed, Cadet et al. (2001) found differential gene expression in the frontal cortex up to 16 h after a 40 mg/kg dose of methamphetamine, although this dose is much higher (32-fold higher) compared to the rather low doses given in our study. Nonetheless, the success of our approach is evident since the changes in gene expression we identified in CA1 reproducibly discriminate HR from LR, as demonstrated in the independent follow-up experiment we performed.

In conclusion, we show that inbred DBA/2 mice exhibit large differences in sensitization to amphetamine that is reflected at the transcriptional level in several dopaminergic output brain areas, but in particular in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. We have identified CRE, Mef2, and GR transcription factors as possible mediators of these differences. CRE, Mef2, and GR signaling appears to form a transcription regulation network involved in the amphetamine susceptibility response and thus may play an important role in psychosis susceptibility. To which extent these systems act as independent, linked, or sequential programs is the target of future studies.

References

Alessi SM, Greenwald M, Johanson CE (2003) The prediction of individual differences in response to D-amphetamine in healthy adults. Behav Pharmacol 14:19–32

Antelman SM, Eichler AJ, Black CA, Kocan D (1980) Interchangeability of stress and amphetamine in sensitization. Science 207:329–331

Badiani A, Cabib S, Puglisi-Allegra S (1992) Chronic stress induces strain-dependent sensitization to the behavioral effects of amphetamine in the mouse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 43:53–60

Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG (2007) The Akt-GSK-3 signaling cascade in the actions of dopamine. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:166–172

Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Vawter M, Ladenheim B (2001) Temporal profiling of methamphetamine-induced changes in gene expression in the mouse brain: evidence from cDNA array. Synapse 41:40–48

Christensen KV, Leffers H, Watson WP, Sanchez C, Kallunki P, Egebjerg J (2010) Levetiracetam attenuates hippocampal expression of synaptic plasticity-related immediate early and late response genes in amygdala-kindled rats. BMC Neurosci 11:9

Dallas PB, Gottardo NG, Firth MJ, Beesley AH, Hoffmann K, Terry PA, Freitas JR, Boag JM, Cummings AJ, Kees UR (2005) Gene expression levels assessed by oligonucleotide microarray analysis and quantitative real-time RT-PCR – how well do they correlate? BMC Genomics 6:59.

Datson NA, Meijer L, Steenbergen PJ, Morsink MC, van der Laan S, Meijer OC et al (2004) Expression profiling in laser-microdissected hippocampal subregions in rat brain reveals large subregion-specific differences in expression. Eur J Neurosci 20:2541–2554

Datson NA, Morsink MC, Steenbergen PJ, Aubert Y, Schlumbohm C, Fuchs E et al (2009) A molecular blueprint of gene expression in hippocampal subregions CA1, CA3, and DG is conserved in the brain of the common marmoset. Hippocampus 19:739–752

de Jong IE, Oitzl MS, de Kloet ER (2007) Adrenalectomy prevents behavioural sensitisation of mice to cocaine in a genotype-dependent manner. Behav Brain Res 177:329–339

De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer AN, Tjon GH, Nestby P, Mulder AH, Vanderschuren LJ (1996) Mifepristone prevents the expression of long-term behavioural sensitization to amphetamine. Eur J Pharmacol 307:R3–R4

Degoulet M, Rouillon C, Rostain JC, David HN, Abraini JH (2008) Modulation by the dorsal, but not the ventral, hippocampus of the expression of behavioural sensitization to amphetamine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 11:497–508

Emamian ES, Hall D, Birnbaum MJ, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA (2004) Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet 36:131–137

Featherstone RE, Kapur S, Fletcher PJ (2007) The amphetamine-induced sensitized state as a model of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31:1556–1571

Flavell SW, Kim TK, Gray JM, Harmin DA, Hemberg M, Hong EJ et al (2008) Genome-wide analysis of MEF2 transcriptional program reveals synaptic target genes and neuronal activity-dependent polyadenylation site selection. Neuron 60:1022–1038

Floresco SB, Todd CL, Grace AA (2001) Glutamatergic afferents from the hippocampus to the nucleus accumbens regulate activity of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 21:4915–4922

Franklin K, Paxinos G (1997) The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 1st edn. Academic, San Diego

Funada M, Zhou X, Satoh M, Wada K (2004) Profiling of methamphetamine-induced modifications of gene expression patterns in the mouse brain. Ann NY Acad Sci 1025:76–83

Gaisler-Salomon I, Miller GM, Chuhma N, Lee S, Zhang H, Ghoddoussi F et al (2009a) Glutaminase-deficient mice display hippocampal hypoactivity, insensitivity to pro-psychotic drugs and potentiated latent inhibition: relevance to schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:2305–2322

Gaisler-Salomon I, Schobel SA, Small SA, Rayport S (2009b) How high-resolution basal-state functional imaging can guide the development of new pharmacotherapies for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 35:1037–1044

Gasbarri A, Verney C, Innocenzi R, Campana E, Pacitti C (1994) Mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons innervating the hippocampal formation in the rat:a combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical study. Brain Res 668:71–79

Goeman JJ, van de Geer SA, de Kort F, van Houwelingen HC (2004) A global test for groups of genes: testing association with a clinical outcome. Bioinformatics 20:93–99

Gong X, Tang X, Wiedmann M, Wang X, Peng J, Zheng D et al (2003) Cdk5-mediated inhibition of the protective effects of transcription factor MEF2 in neurotoxicity-induced apoptosis. Neuron 38:33–46

Grace AA (2010) Dopamine system dysregulation by the ventral subiculum as the common pathophysiological basis for schizophrenia psychosis, psychostimulant abuse, and stress. Neurotox Res 18:367–376

Grace AA, Floresco SB, Goto Y, Lodge DJ (2007) Regulation of firing of dopaminergic neurons and control of goal-directed behaviors. Trends Neurosci 30:220–227

Hermens DF, Lubman DI, Ward PB, Naismith SL, Hickie IB (2009) Amphetamine psychosis: a model for studying the onset and course of psychosis. Med J Aust 190:S22–S25

Holmes A, le Guisquet AM, Vogel E, Millstein RA, Leman S, Belzung C (2005) Early life genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29:1335–1346

Janowsky DS, Risch C (1979) Amphetamine psychosis and psychotic symptoms. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 65:73–77

Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R et al (2004) Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109:38–45

Johns LC, Cannon M, Singleton N, Murray RM, Farrell M, Brugha T et al (2004) Prevalence and correlates of self-reported psychotic symptoms in the British population. Br J Psychiatry 185:298–305

King EM, Holden NS, Gong W, Rider CF, Newton R (2009) Inhibition of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription by MKP-1: transcriptional repression by glucocorticoids occurring via p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem 284:26803–26815

Kino T, Ichijo T, Amin ND, Kesavapany S, Wang Y, Kim N et al (2007) Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 differentially regulates the transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid receptor through phosphorylation: clinical implications for the nervous system response to glucocorticoids and stress. Mol Endocrinol 21:1552–1568

Kodama M, Akiyama K, Ujike H, Shimizu Y, Tanaka Y, Kuroda S (1998) A robust increase in expression of arc gene, an effector immediate early gene, in the rat brain after acute and chronic methamphetamine administration. Brain Res 796:273–283

Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DE, Truong HT et al (2005) Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron 48:303–314

Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A (1999) Dopamine as the wind of the psychotic fire: new evidence from brain imaging studies. J Psychopharmacol 13:358–371

Lataster T, Wichers M, Jacobs N, Mengelers R, Derom C, Thiery E et al (2009) Does reactivity to stress cosegregate with subclinical psychosis? A general population twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119:45–53

Levesque D, Rouillard C (2007) Nur77 and retinoid X receptors: crucial factors in dopamine-related neuroadaptation. Trends Neurosci 30:22–30

Lisman JE, Grace AA (2005) The hippocampal-VTA loop: controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron 46:703–713

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408

Lockwood JA, Turney TH (1981) Social dominance and stress-induced hypertension: strain differences in inbred mice. Physiol Behav 26:547–549

Lodge DJ, Grace AA (2007) Aberrant hippocampal activity underlies the dopamine dysregulation in an animal model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci 27:11424–11430

Lodge DJ, Grace AA (2008) Amphetamine activation of hippocampal drive of mesolimbic dopamine neurons: a mechanism of behavioral sensitization. J Neurosci 28:7876–7882

Mathews IZ, Mills RG, McCormick CM (2008) Chronic social stress in adolescence influenced both amphetamine conditioned place preference and locomotor sensitization. Dev Psychobiol 50:451–459

McClung CA, Nestler EJ (2003) Regulation of gene expression and cocaine reward by CREB and DeltaFosB. Nat Neurosci 6:1208–1215

McClung CA, Ulery PG, Perrotti LI, Zachariou V, Berton O, Nestler EJ (2004) DeltaFosB: a molecular switch for long-term adaptation in the brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 132:146–154

McCoy MT, Jayanthi S, Wulu JA, Beauvais G, Ladenhei B, Martin TA, Krasnova IN, Hodges AB, Cadet JL (2011) Chronic methamphetamine exposure suppresses the striatal expression of members of multiple families of immediate early genes (IEGs) in the rat: normalization by an acute methamphetamine injection. Psychopharmacology. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-2146-7]

Mirnics K, Middleton FA, Marquez A, Lewis DA, Levitt P (2000) Molecular characterization of schizophrenia viewed by microarray analysis of gene expression in prefrontal cortex. Neuron 28:53–67

Mlewski EC, Krapacher FA, Ferreras S, Paglini G (2008) Transient enhanced expression of Cdk5 activator p25 after acute and chronic d-amphetamine administration. Ann NY Acad Sci 1139:89–102

Mondelli V, Dazzan P, Hepgul N, Di Forti M, Aas M, D’Albenzio A et al (2010a) Abnormal cortisol levels during the day and cortisol awakening response in first-episode psychosis: the role of stress and of antipsychotic treatment. Schizophr Res 116:234–242

Mondelli V, Pariante CM, Navari S, Aas M, D’Albenzio A, Di Forti M et al (2010b) Higher cortisol levels are associated with smaller left hippocampal volume in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 119:75–78

Morgan C, Fisher H (2007) Environment and schizophrenia:environmental factors in schizophrenia:childhood trauma—a critical review. Schizophr Bull 33:3–10

Morrens M, Hulstijn W, Lewi PJ, De Hert M, Sabbe BG (2006) Stereotypy in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 84:397–404

Morris MS, Morey AF, Stackhouse DA, Santucci RA (2006) Fibrin sealant as tissue glue: preliminary experience in complex genital reconstructive surgery. Urology 67:688–691 (discussion 691–682)

Morsink MC, Steenbergen PJ, Vos JB, Karst H, Joels M, De Kloet ER et al (2006) Acute activation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors results in different waves of gene expression throughout time. J Neuroendocrinol 18:239–252

Myin-Germeys I, van Os J (2007) Stress-reactivity in psychosis: evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev 27:409–424

Nestler EJ (2005a) Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci 8:1445–1449

Nestler EJ (2005b) The neurobiology of cocaine addiction. Sci Pract Perspect 3:4–10

Okabe T, Takayanagi R, Adachi M, Imasaki K, Nawata H (1998) Nur77, a member of the steroid receptor superfamily, antagonizes negative feedback of ACTH synthesis and secretion by glucocorticoid in pituitary corticotrope cells. J Endocrinol 156:169–175

Palmer AA, Verbitsky M, Suresh R, Kamens HM, Reed CL, Li N et al (2005) Gene expression differences in mice divergently selected for methamphetamine sensitivity. Mamm Genome 16:291–305

Pawitan Y, Michiels S, Koscielny S, Gusnanto A, Ploner A (2005) False discovery rate, sensitivity and sample size for microarray studies. Bioinformatics 21:3017–3024

Peleg-Raibstein D, Sydekum E, Feldon J (2006) Differential effects on prepulse inhibition of withdrawal from two different repeated administration schedules of amphetamine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 9:737–749

Peleg-Raibstein D, Knuesel I, Feldon J (2008) Amphetamine sensitization in rats as an animal model of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res 191:190–201

Peleg-Raibstein D, Yee BK, Feldon J, Hauser J (2009) The amphetamine sensitization model of schizophrenia: relevance beyond psychotic symptoms? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206:603–621

Pfenning AR, Schwartz R, Barth AL (2007) A comparative genomics approach to identifying the plasticity transcriptome. BMC Neurosci 8:20

Philips A, Maira M, Mullick A, Chamberland M, Lesage S, Hugo P et al (1997) Antagonism between Nur77 and glucocorticoid receptor for control of transcription. Mol Cell Biol 17:5952–5959

Post RM (1992) Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 149:999–1010

Pulipparacharuvil S, Renthal W, Hale CF, Taniguchi M, Xiao G, Kumar A et al (2008) Cocaine regulates MEF2 to control synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron 59:621–633

Purves DAG, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO, White LE (2008) Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, pp 170–176

Rossato JI, Bevilaqua LR, Izquierdo I, Medina JH, Cammarota M (2009) Dopamine controls persistence of long-term memory storage. Science 325:1017–1020

Schobel SA, Lewandowski NM, Corcoran CM, Moore H, Brown T, Malaspina D et al (2009) Differential targeting of the CA1 subfield of the hippocampal formation by schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:938–946

Scholl JL, Feng N, Watt MJ, Renner KJ, Forster GL (2009) Individual differences in amphetamine sensitization, behavior and central monoamines. Physiol Behav 96:493–504

Seeman P, Weinshenker D, Quirion R, Srivastava LK, Bhardwaj SK, Grandy DK et al (2005) Dopamine supersensitivity correlates with D2High states, implying many paths to psychosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:3513–3518

Seeman P, McCormick PN, Kapur S (2007) Increased dopamine D2(High) receptors in amphetamine-sensitized rats, measured by the agonist [(3)H](+)PHNO. Synapse 61:263–267

Segal DS, Geyer MA, Schuckit MA (1981) Stimulant-induced psychosis: an evaluation of animal methods. Essays Neurochem Neuropharmacol 5:95–129

Shaw-Lutchman TZ, Impey S, Storm D, Nestler EJ (2003) Regulation of CRE-mediated transcription in mouse brain by amphetamine. Synapse 48:10–17

Shevlin M, Houston JE, Dorahy MJ, Adamson G (2008) Cumulative traumas and psychosis: an analysis of the national comorbidity survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr Bull 34:193–199

Shilling PD, Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Barrett TB, Kelsoe JR (2006) Differential regulation of immediate-early gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of rats with a high vs low behavioral response to methamphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:2359–2367

Shohamy D, Adcock RA (2010) Dopamine and adaptive memory. Trends Cogn Sci 14:464–472

Silva AJ, Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Kida S (1998) CREB and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 21:127–148

Simon R, Lam A, Li MC, Ngan M, Menenzes S, Zhao Y (2007) Analysis of gene expression data using BRB-ArrayTools. Can Inf 3:11–17

Sokolov BP, Polesskaya OO, Uhl GR (2003) Mouse brain gene expression changes after acute and chronic amphetamine. J Neurochem 84:244–252

Strakowski SM, Sax KW, Setters MJ, Stanton SP, Keck PE Jr (1997) Lack of enhanced response to repeated d-amphetamine challenge in first-episode psychosis: implications for a sensitization model of psychosis in humans. Biol Psychiatry 42:749–755

Tenn CC, Fletcher PJ, Kapur S (2003) Amphetamine-sensitized animals show a sensorimotor gating and neurochemical abnormality similar to that of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 64:103–114

Thierry AM, Gioanni Y, Degenetais E, Glowinski J (2000) Hippocampo-prefrontal cortex pathway: anatomical and electrophysiological characteristics. Hippocampus 10:411–419

Valjent E, Corvol JC, Trzaskos JM, Girault JA, Herve D (2006) Role of the ERK pathway in psychostimulant-induced locomotor sensitization. BMC Neurosci 7:20

Vanderschuren LJ, Schmidt ED, De Vries TJ, Van Moorsel CA, Tilders FJ, Schoffelmeer AN (1999) A single exposure to amphetamine is sufficient to induce long-term behavioral, neuroendocrine, and neurochemical sensitization in rats. J Neurosci 19:9579–9586

Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR et al (2004) Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci 7:847–854

Wicks S, Hjern A, Gunnell D, Lewis G, Dalman C (2005) Social adversity in childhood and the risk of developing psychosis: a national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 162:1652–1657

Wiles NJ, Zammit S, Bebbington P, Singleton N, Meltzer H, Lewis G (2006) Self-reported psychotic symptoms in the general population: results from the longitudinal study of the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry 188:519–526

Wu J, Xie X (2006) Comparative sequence analysis reveals an intricate network among REST, CREB and miRNA in mediating neuronal gene expression. Genome Biol 7:R85

Yamagata K, Suzuki K, Sugiura H, Kawashima N, Okuyama S (2000) Activation of an effector immediate-early gene arc by methamphetamine. Ann NY Acad Sci 914:22–32

Yao W-D, Gainetdinov RR, Arbuckle MI, Sotnikova TD, Cyr M, Beaulieu J-M, Torres GE, Grant SGN, Caron MG (2004) Identification of PSD-95 as a regulator of dopamine-mediated synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron 41:625–638

Yuferov V, Nielsen D, Butelman E, Kreek MJ (2005) Microarray studies of psychostimulant-induced changes in gene expression. Addict Biol 10:101–118

Zhang X, Odom DT, Koo SH, Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Best J et al (2005) Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:4459–4464

Zhang J, Zhang L, Jiao H, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Lou D et al (2006) c-Fos facilitates the acquisition and extinction of cocaine-induced persistent changes. J Neurosci 26:13287–13296

Disclosure/conflicts of interest

I.E.M. de Jong, K. Vielsted Christensen, K. Potempa, J. Torleif Pedersen, J. Egebjerg, P. Kallunki, E.B. Nielsen, and M. Didriksen are all full-time employees of H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

N.A. Datson and N. Speksnijder contributed equally to this work.

Grant sponsor

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) grant 836.06.010 (MEERVOUD) to N.A. Datson and TI Pharma T5-209. E.R. de Kloet was supported by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Science.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Fig. S1

No correlation is observed in total brain exposure to amphetamine and locomotor activity of high and low responders to amphetamine (DOC 54 kb)

Table SI

Sequences of the primers used for validated genes in the three brain areas: CA1, Nac, and PFC (DOC 58 kb)

Table SII

CA1 differentially expressed genes sorted by FC of the univariate test (DOC 352 kb)

Table III

Gene list sources for IPA Publist analyses (DOC 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Datson, N.A., Speksnijder, N., de Jong, I.E.M. et al. Hippocampal CA1 region shows differential regulation of gene expression in mice displaying extremes in behavioral sensitization to amphetamine: relevance for psychosis susceptibility?. Psychopharmacology 217, 525–538 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2313-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2313-5