Abstract

Rationale

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) differs from other types of hallucinogens in that it possesses direct dopaminergic effects. The exact nature of this component has not been elucidated.

Objective

The present study sought to characterize the effects of several dopamine D4 agonists and antagonists on the discriminative stimulus effect of LSD at two pretreatment times and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI), a selective 5-HT2A/2C agonist.

Materials and methods

Male Sprague–Dawley rats were trained in a two-lever, fixed ratio (FR) 50, food-reinforced task with LSD-30 (0.08 mg/kg, i.p., 30-min pretreatment time), LSD-90 (0.16 mg/kg, i.p., 90-min pretreatment time), and DOI (0.4 mg/kg, i.p., 30-min pretreatment time) as discriminative stimuli. Substitution and combination tests with the dopamine D4 agonists, ABT-724 and WAY 100635, were performed in all groups. Combination tests were run using the dopamine D4 antagonists A-381393 and L-745,870 and two antipsychotic drugs, clozapine and olanzapine.

Results

WAY 100635 produced full substitution in LSD-90 rats, partial substitution in LSD-30 rats, and saline appropriate responding in DOI-trained rats. ABT-724 partially mimicked the LSD-90 and LSD-30 cues, but produced no substitution in DOI-trained rats. In combination tests, both agonists shifted the dose–response curve of LSD leftward, most potently for the LSD-90 cue. The D4 antagonists significantly attenuated both the LSD-90 and LSD-30 cue, but had no effect on the DOI cue.

Conclusion

Dopamine D4 receptor activation plays a significant modulatory role in the discriminative stimulus effects in LSD-90-trained rats, most markedly for the later temporal phase of LSD, but has no effect on the cue produced by DOI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Activation of the serotonin2A (5-HT2A) receptor is essential for the effects of hallucinogens (see review by Nichols 2004). These receptors are particularly important in prefrontal cortical function where they are found at high densities in many species (Miner et al. 2003; Xu and Pandey 2000). Cortical 5-HT2A receptors also are hypothesized to be involved in the pathology and treatment of schizophrenia (Meltzer 1999; Aghajanian and Marek 2000). Although the pyramidal neuron is the major cortical cell type expressing 5-HT2A receptors, some cortical GABAergic interneurons also express these receptors (Griffiths and Lovick 2002; de Almeida and Mengod 2007).

In drug discrimination assays in rats, the interoceptive cue generated by hallucinogenic phenethylamine derivatives such as 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI) or 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine is monophasic, lasts for several hours after drug administration, and is mediated by stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors (e.g., Glennon 1986; Klodzinska and Chojnacka-Wojcik 1997; Smith et al. 1999). Phenethylamines such as DOI show high affinity only at 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors without detectable effects at other G-protein-coupled receptors, channels, or transporters (http://kidb.cwru.edu/pdsp.php).

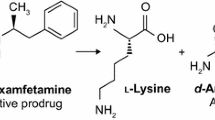

The potent hallucinogen lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) displays high affinity for 5-HT2 family receptors, but it also has high affinity at many other monoamine receptors (http://kidb.cwru.edu/pdsp.php). Although it has been known for a long time that LSD has direct dopaminergic properties (see Watts et al. 1995 and references therein), activation of 5-HT2A receptors is thought to mediate its hallucinogenic properties as well as its interoceptive cue in drug discrimination studies. That is, when rats are administered LSD (0.08 or 0.16 mg/kg) 30 min before discrimination training, the cue is mediated primarily by 5-HT2A receptor activation.

We have previously demonstrated, however, that the discriminative stimulus effect of LSD in rats proceeds through two temporal phases (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005). The first phase is mediated by stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors, reaches a maximum 15–30 min after drug administration, and lasts about 1 h, a finding that has been replicated in numerous laboratories (e.g., Colpaert et al. 1982; Glennon et al. 1984; Winter et al. 1999). The second phase of action for LSD appears to be mediated by activation of dopamine D2-like receptors (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005) and reaches a maximum at times from 60 to 90 min after LSD administration. That is, when LSD (0.16 mg/kg) is administered 90 min prior to discrimination training, it produces a robust interoceptive cue that is mediated primarily by dopamine D2-like receptor activation.

Thus, in drug discrimination studies, LSD has a biphasic pharmacology, with an initial phase mediated by 5-HT2A receptor activation and a delayed temporal phase that is mediated by D2-like dopamine receptor stimulation (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005, 2007). Although a larger dose of LSD is necessary to maintain the salience of a cue out to 90 min, when the higher dose of LSD is administered 30 min prior to discrimination training, the cue is still mediated by 5-HT2A receptor activation (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005). Thus, the length of time between LSD administration and discrimination training is the key factor that determines the nature of the discriminative cue. Our findings in rats parallel the observations of Freedman (1984) that the psychological effects of LSD in humans occur in two time-dependent phases.

Hallucinogens may activate dopaminergic pathways either directly, as with LSD, or indirectly by compounds that lack significant dopamine receptor affinity (Bortolozzi et al. 2005; Ichikawa and Meltzer 1995; Pehek et al. 2006; Vollenweider et al. 1999). For example, it is well documented that activation of the 5-HT2A receptor can modulate dopamine levels or physiological responses mediated by dopaminergic systems (Alex and Pehek 2007; Lucas and Spampinato 2000; Pehek et al. 2001; Vollenweider et al. 1999; Yan 2000). In addition, it has been reported previously that pretreatment with 5-HT2A agonists can potentiate the discriminative stimulus effects of amphetamine (Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 1997), methamphetamine (Munzar et al. 1999, 2002), and cocaine (Munzar et al. 2002) in rats. Although studies of hallucinogen-mediated dopaminergic effects or action at dopamine receptors are sparse, this area appears promising for further study.

Little is known, however, concerning the role of specific dopamine D2 receptor subtypes in the effects of LSD. In an earlier study, we reported that WAY 100635, a mixed 5-HT1A antagonist/D4 agonist (Chemel et al. 2006a) produced partial substitution in rats trained to discriminate LSD following a 30 min pretreatment time, and full substitution in rats trained to discriminate LSD after a 90-min pretreatment time (Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 2007).

In the present study, we examine for the first time the involvement of dopamine D4 receptors (Van Tol et al. 1991) in the discriminative stimulus effects of LSD (30- and 90-min pretreatment times) and the hallucinogenic amphetamine derivative, DOI. In addition, LSD and DOI radioligand competition binding studies were performed using HEK cell lines stably expressing human D4.4 dopamine receptors. The potency and intrinsic activity of LSD at the dopamine D4 receptor was determined by its ability to inhibit forskolin-stimulated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighing 180–200 g at the beginning of the study were used as subjects. Rats were divided into three groups and trained to discriminate LSD (186 nmol/kg, 0.08 mg/kg, i.p.) with a 30-min pretreatment time (LSD-30), LSD (372 nmol/kg, 0.16 mg/kg, i.p.) with a 90-min pretreatment time (LSD-90), and DOI (1.12 μmol/kg, 0.4 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min before training) from saline using a two-lever, food-reinforced operant conditioning task. All experimental conditions and the feeding procedure were described in detail in our previous paper (Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 2007). Animals used in these studies were maintained in accordance with the US Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as amended August 2002, and the protocol was approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

Six standard operant conditioning chambers (model E10-10RF, Coulbourn Instruments, Lehigh Valley, PA, USA) consisted of modular test cages enclosed within sound-attenuated cubicles with fans for ventilation and background white noise. A white house light was centered near the top of the front panel of the cage, which also was equipped with two response levers, separated by a food hopper (combination dipper pellet trough, model E14-06, module size 1/2) all positioned 2.5 cm above the floor. Solid state logic in an adjacent room, interfaced through a Med Associates (Lafayette, IN, USA) interface to a personal computer, controlled reinforcement and data acquisition with locally written software.

Discrimination training and testing

A FR 50 schedule of food reinforcement (45 mg dustless pellets, Research Diets, NJ, USA) in a two-lever paradigm was used. The drug discrimination procedure details have been described elsewhere (Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 1994). At least one drug and one saline session separated each test session, and rats were required to maintain the 85% correct responding criterion on the two prior training days in order to be tested. In addition, test data were discarded when the accuracy criterion of 85% was not achieved on either of the two training sessions following a test session. Training sessions lasted 15 min, and test sessions lasted 5 min and were run under conditions of extinction, with rats removed from the operant chamber when 50 presses were emitted on either lever. In a test session, if 50 presses on one lever were not completed within 5 min, the session was ended and scored as a disruption. For substitution tests, drugs were administered i.p. 30 min prior to test sessions. Inhibition tests were carried out by administering different doses of antagonist 30 min before the training dose of training drugs, that is, 60 min before tests in LSD-30 and DOI-trained rats and 120 min in LSD-90-trained animals. For combination tests, a single dose chosen from substitution or inhibition tests for agonists or antagonists, respectively, was administered 30 min before different doses of training drug. For a dose–response effect of the training drugs, all groups of rats were tested when they first passed the required criteria and later at least once during each 8-month period.

Drugs

The training drugs used were LSD [(+)-lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate, NIDA] and DOI [1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane hydrochloride, synthesized in our laboratory]. LSD training doses were 0.08 mg/kg (186 nmol/kg) or 0.16 mg/kg (372 nmol/kg.), and the training dose used for DOI was 0.4 mg/kg (1.12 μmol/kg). WAY 100635 (N-[2-[4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl]-N-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexanecarboxamide), ABT-724, A-381393 (2-[4-(3,4-dimethylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylmethyl]-1H-benzimidazole), and WAY 100635 were prepared in our synthesis laboratory using previously reported methods (Nakane et al. 2005; Zhuang et al. 1994). Other drugs used for this study include: L-745,870 (3-[[4-(4-chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]methyl]-1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine trihydrochloride) and clozapine (8-chloro-11-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-5H-dibenzo[b,e][1,4]diazepine), which were purchased from TOCRIS (Ellisville, MO, USA). Olanzapine hydrochloride was a generous gift from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All drug solutions were prepared by dissolving the compounds in sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) at a concentration that allowed the appropriate dose to be given in a volume of 1 ml/kg, identical to the volume of the saline injection. Stock solutions of clozapine (10 mg/ml) and olanzapine (10 mg/ml) were prepared by dissolving the drugs in a minimal volume (one to two drops) of 80% l-lactic acid followed by dilution with distilled water to the desired concentration (final pH 6.2–6.7).

Chemicals and reagents used for in vitro experiments were as follows: [3H]Spiperone (95 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). [3H]Cyclic AMP (30 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Perkin Elmer life and analytical sciences (Boston, MA, USA). Quinpirole, dopamine, spiperone, butaclamol, isobutylmethylxanthine, forskolin, and most other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). Growth media, antibiotics, and most other cell culture reagents were purchased from Gibco Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Cell culture

HEK-hD4.4 stable cells were created previously (Watts et al. 1999) and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 5% fetal clone serum, 5% bovine calf serum, 0.05 μg/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 μg/ml puromycin. Cells were grown on 10-cm tissue culture plates in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cyclic AMP accumulation assay

Cells were grown to confluent monolayers in 48-well clear tissue culture plates. Prior to assay, growth media was decanted and the plates placed on ice. Drug dilutions made in Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) assay buffer (EBSS containing 2% bovine calf serum, 0.025% ascorbic acid, and 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) were added on ice. cAMP accumulation was stimulated by 5 μM forskolin, and each assay was performed in the presence of 500 μM isobutylmethylxanthine. Incubations were performed for 15 min in a 37°C water bath. To terminate the stimulation, the assay media was decanted and cells were lysed by adding 100 μl of 3% trichloroacetic acid on ice. Plates were stored at 4°C for at least 1 h before quantification of cAMP.

Quantification of cyclic AMP

Cyclic AMP accumulation was assessed using a previously described competition binding assay (Watts and Neve 1996). Briefly, cell lysate (12 μl) was added in duplicate to assay tubes with cAMP binding buffer [100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)] containing [3H]cAMP (1 nM final concentration) and cAMP binding protein (100–150 μg in 500 μl buffer). The reaction tubes were incubated on ice at 4°C for 2–3 h before harvesting by filtration (GF/C filterplates; Whatman, Maidstone, UK) using a 96-well Packard Filtermate cell harvester. Filter plates were dried, and 30 μl of Packard Microscint O scintillation fluid was added to each well. Radioactivity per well was determined using a Packard TopCount scintillation counter. The concentration of cAMP in each sample was estimated from a standard curve ranging from 0.01 to 300 pmol of cyclic AMP.

Radioligand competition assay

Cells were grown to confluence on 15-cm plates. Growth media was decanted and replaced with 10 ml ice-cold lysis buffer (1 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 2 mM EDTA). After 10 min, cells were scraped from the plate and centrifuged at 30,000×g and 4°C for 20 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 4 ml receptor binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, and 4 mM MgCl) using a Kinematica homogenizer at a setting of 6 for 5 s before 1.0 ml aliquots were centrifuged again at 13,000×g for 10 min. The pellets were stored at −80°C until use.

Pellets were then resuspended for use by trituration in receptor binding buffer (50 μg protein/100 μl) and added in duplicate to assay tubes containing 0.1–0.2 nM [3H]spiperone and appropriate drugs. Non-specific binding was determined using 5 μM (+)-butaclamol. Assay tubes were incubated at 37°C for 30 min before filtration, as described for cAMP binding assays. Filter plates were dried, 30 μl of Packard Microscint O scintillation fluid was added to each well, and radioactivity per well was determined using a Packard TopCount scintillation counter.

Data analysis

Data from the drug discrimination study were scored in a quantal fashion with the lever on which the rat first emitted 50 presses in a test session scored as the “selected” lever. The percentage of rats selecting the drug lever (%SDL) for each dose of test compound was determined. Full, partial, and no substitution were statistically determined using a binomial test (Zar 1999). This test is very conservative, and additional details for the use of the binomial test to analyze quantal drug discrimination data are provided in our earlier publication (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005). If the drug was one that completely substituted for the training drug, the method of Litchfield and Wilcoxon (1949) was used to determine the ED50 and 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

GraphPad Prism software was used to generate dose–response and competition binding curves (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data from cAMP inhibition assays were normalized to percent maximum forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. IC50 values were generated by GraphPad Prism using the sigmoidal dose–response (variable slope) equation. K 0.5 values for agonists were calculated from IC50 values by GraphPad Prism using the Cheng–Prusoff equation (Cheng and Prusoff 1973).

Results

Generalization tests with D4 agonists

Figure 1 shows results from generalization tests for the highly selective D4 dopamine agonists ABT-724 (Cowart et al. 2004) and for the mixed 5-HT1A antagonist/D4 agonist WAY100635 (Chemel et al. 2006a) tested in DOI (Fig. 1a), LSD-30 (Fig. 1b), and LSD-90 (Fig. 1c) rats. Neither compound mimicked DOI at any dose tested, although WAY 100635 produced a significantly higher percentage of disruption than ABT-724 in DOI-trained rats. Data from generalization tests for both D4 receptor agonists were presented earlier (Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 2007), but we included them for comparison with results from substitution tests in DOI-trained rats. ABT-724 produced partial substitution in both LSD-30- and LSD-90-trained rats, with a bell-shaped dose–response curve in LSD-30 rats (62.5% maximum %SDL). The doses of WAY 100635 required for effects in the generalization tests were about ten times larger than those of ABT-724. To test for significant differences in the maximum degree of WAY 100635 substitution in each colony of rats, the Pearson χ 2 statistic (8.325, 2 df) gave p = 0.016, indicating that the proportion of responding rats in these three conditions is not plausibly the same. Further, maximal drug-appropriate responding in the LSD-30 rats is intermediate between the DOI and LSD-90 rats, tested using a χ 2 test for linear trend (χ 2, 1 df = 8.27, p = 0.004).

Results from substitution tests with the dopamine D4 agonist ABT 724 and 5-HT1A antagonist/D4 agonist WAY 100635 performed in rats trained to discriminate DOI (a, upper panel), LSD-30 (b, middle panel), and LSD-90 (c, bottom panel) rats. All drugs were injected 30 min before tests. %SDL is the percentage of rats that selected the drug-appropriate level. N = 6–14 rats per data point. Right Y-axis and open symbols show the percentage of rats disrupted. Data from LSD-trained rats were presented in Marona-Lewicka and Nichols (2007)

Results from combination tests of different doses of dopamine D4 antagonists on discrimination of the training drugs

Pretreatment with WAY 100635 had no effect on the discriminative stimulus of DOI, although the highest dose of WAY 100635 inhibited the response rate, producing as much as 75% disruption (Fig. 2a). The lowest doses of WAY 100635 had an inhibitory effect LSD-30, but this effect was lost as the dose was increased, with no effect at the two highest doses of WAY 100635 (10 and 20 μmol/kg; Fig. 2b). The low dose of WAY 100635 (0.74 μmol/kg) produced the greatest inhibitory effect against the LSD-30 cue, whereas the high dose (10 μmol/kg) had no effect on the stimulus effects of the training dose of LSD in LSD-30 rats. This divergent effect of WAY 100635 on the LSD-30 cue prompted us to use two different doses of WAY 100635 in subsequent combination tests with different doses of LSD.

Results from combination tests of different doses of the dopamine D4 antagonists: L-745,870 (diamonds) and A381393 (inverted triangles), the 5-HT1A antagonist/D4 agonist WAY 100635 (squares), and the atypical antipsychotic drugs: clozapine (circles), and olanzapine (triangles) with 1.12 μmol/kg of DOI in DOI-trained rats (a, upper panel), 186 nmol/kg of LSD in LSD-30-trained rats (b, middle panel), and 372 nmol/kg of LSD in LSD-90-trained rats (c, bottom panel). All drugs were injected 30 min prior to the training drug. %SDL is the percentage of rats that selected the drug-appropriate lever. Right Y-axis and open symbols show the percentage of rats disrupted. N = 6–20 rats per data point

In contrast to the marked inhibition by low doses of WAY 100635 on the LSD-30 cue, it inhibited the LSD-90 cue by only 20% at the lowest dose (Fig. 2c). This inhibition was not statistically significant because 80% of the rats were still able to emit drug-appropriate responses, a condition scored as full substitution. Moreover, WAY 100635 did not produce significant behavior disruption in LSD-90-trained rats (Fig. 2c).

The selective D4 antagonist L-745,870 (Patel et al. 1997) had no effect on DOI discrimination (Fig. 2a), but produced significant disruption of behavior. L-745,870 partially inhibited LSD-30 (Fig. 2b), but more strongly antagonized the discriminative stimulus effects in LSD-90 rats (Fig. 2c). Similar to the results with WAY 100635, this combination did not produce significant behavioral disruption. Unfortunately, the limited amount of L 745,870 available precluded testing additional doses. Another selective D4 antagonist A381393 produced effects similar to L-745,870 (Fig. 2a–c) in all groups of rats. The 10-μmol/kg dose of A381393 produced significant inhibitory effects in LSD-90 rats, induced a relatively low percentage of disruption, and therefore was chosen for more extensive combination tests.

The atypical antipsychotic drugs clozapine and olanzapine, which have both 5-HT2A and dopamine D4 antagonist activity (Roth et al. 1995; Meltzer 1999; Seeman et al. 1997; Richelson and Souder 2000), showed a significant inhibitory effect when tested in combination with training drugs in all three groups of rats (Fig. 2). In combination with DOI (Fig. 2a) or LSD-30 (Fig. 2b), however, they also produced a high percentage of disruption. In contrast, clozapine and olanzapine blocked drug-appropriate lever selection in more than 80% of LSD-90-trained rats without affecting their response rate (Fig. 2c). The inhibitory effects of these atypical antipsychotics, based on the data presented in Fig. 2, were strongest against the LSD-90 cue, were less pronounced against the LSD-30 cue, and only partially inhibited the DOI cue.

Results of combining the dopamine D4 agonist ABT-724 with different doses of training drugs

Co-administration of ABT-724 with DOI (Fig 3a) significantly decreased drug-appropriate lever selection for the 0.28 and 0.56 μmol/kg doses of DOI, but was without effect when combined with the 1.12 μmol/kg training dose of DOI. The ED50 for this combination was not significantly different than for DOI alone (Table 1).

Results from combination tests of the dopamine D4 agonist ABT 724 (0.5 μmol/kg, 0.2 mg/kg) with different doses of DOI in DOI-trained rats (a, upper panel), with different doses of LSD in LSD-30-trained rats (b, middle panel), and in LSD-90-trained rats (c, bottom panel). ABT 724 was injected 30 min before the training drug. %SDL is the percentage of rats that selected the drug-appropriate lever. N = 8–16 rats per data point. There was 0% disruption for DOI, LSD-30 and LSD-90 alone for all doses tested

Co-administration of the D4 dopamine agonist ABT-724 with LSD in LSD-30 rats produced a bimodal effect (Fig. 3b). We observed potentiation of the discriminative effect at low doses of LSD, but attenuation of drug-appropriate responding at higher doses of LSD.

The effect of ABT-724 on the LSD-90 cue was, however, quite remarkable, with significant potentiation of the LSD effect (Fig. 3c). The ED50 of LSD for this combination is more than twofold lower than for LSD-90 alone (Table 1). Yet, the shift in ED50 fails to convey the very steep dose–response curve evident in Fig. 3c.

The results of combining a low dose of the 5-HT1A antagonist/dopamine D4 agonist WAY 100635 with different doses of training drugs

Administration of 0.74 μmol/kg of WAY 100635 prior to DOI decreased drug-appropriate responding only for the 0.56 μmol/kg dose of DOI (Fig. 4a), whereas it was without effect either at the lower or higher dose of DOI.

Results from combination tests with the low dose (0.74 μmol/kg; 0.4 mg/kg) of WAY 100635 and different doses of DOI in DOI-trained rats (a, upper panel), with different doses of LSD in LSD-30-trained rats (b, middle panel), and in LSD-90-trained rats (c, bottom panel). WAY 100635 was administered 30 min before the training drug. %SDL is the percentage of rats that selected the drug-appropriate lever. N = 8–16 rats per data point. There was 0% disruption for DOI, LSD-30, and LSD-90 alone for all doses tested

Figure 4b shows the effect of combining different doses of LSD with 0.74 μmol/kg of WAY 100635 administered 30 min before LSD (60 min before testing). At this dose, WAY 100635 slightly increased the %SDL when combined with the lower 23 and 46.5 nmol/kg doses of LSD, but significantly decreased drug-appropriate responding in LSD-30 rats when combined with higher LSD doses, although the difference between the ED50 for the combination and for LSD alone was not significant (Table 1). Moreover, this combination did not produce a simple rightward shift of the dose-dependent response. The cue produced by the combination of WAY 100635 plus LSD is not parallel to the cue generated by LSD alone, suggesting that a mechanism different from simple antagonism is involved. Similar results were observed in LSD-90-trained rats (Fig. 4c), but a combination of 0.74 μmol/kg of WAY 100635 with 93 nmol/kg of LSD in LSD-90 rats was without effect on drug-appropriate responding, whereas in LSD-30 rats, the same combination significantly decreased drug-appropriate lever selection.

The results of combination tests of a high dose of the 5-HT1A antagonist/dopamine D4 agonist WAY 100635 with different doses of training drugs

Combinations of 10 μmol/kg of WAY 100635 with DOI (a), LSD-30 (b), and LSD-90 (c) gave the results shown in Fig. 5. Pretreatment with the high dose of WAY 100635 produced a leftward but non-significant shift of the dose–response curve for both DOI and LSD-30. By contrast, the 10-μmol/kg dose of WAY 100635 significantly enhanced drug-appropriate lever selection when combined with different doses of LSD in LSD-90 rats (Fig. 5c), with a significant difference between the ED50 for this combination versus LSD-90 alone (Table 1).

Results from combination tests with the higher dose of WAY 100635 (10 μmol/kg; 5.4 mg/kg) and different doses of DOI in DOI-trained rats (a, upper panel), with different doses of LSD in LSD-30-trained rats (b, middle panel), and in LSD-90-trained rats (c, bottom panel). WAY 100635 was administered 30 min before the training drug. %SDL is the percentage of rats that selected the drug-appropriate lever. N = 8–16 rats per data point. There was 0% disruption for DOI, LSD-30, and LSD-90 alone for all doses tested

The results of combination tests of the dopamine D4 antagonist A-381393 with different doses of training drugs

Results from combination tests with the selective dopamine D4 receptor antagonist A-381393 are presented in Fig. 6. A-381393 had no effect on the DOI cue (Fig. 6a), but pretreatment with 10 μmol/kg before different doses of LSD in LSD-30 (Fig. 6b) or in LSD-90 (Fig. 6c) rats inhibited drug-appropriate lever selection, especially at the higher doses of LSD. In LSD-90-trained rats, the combination of A-381393 with LSD produced a more than sixfold shift to the right compared with LSD alone (Table 1).

Results from combination tests of the dopamine D4 antagonist A381393 (10 μmol/kg, 4.37 mg/kg) with different doses of DOI in DOI-trained rats (a, upper panel), with different doses of LSD in LSD-30-trained rats (b, middle panel), and in LSD-90-trained rats (c, bottom panel). A381393 was administered 30 min before the training drug. %SDL is the percentage of rats that selected the drug-appropriate lever. N = 8–16 rats per data point. There was 0% disruption for DOI, LSD-30, and LSD-90 alone for all doses tested

WAY 100635, dopamine D4 receptor antagonists, and atypical antipsychotic drugs have significant affinity at the dopamine D4 receptor

Table 2 presents data from radioligand competition binding experiments and from inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in HEK cells stably expressing the human dopamine D4.4 receptor. Competition binding experiments were performed with [3H]spiperone to label the hD4.4 receptor; this radioligand had a K d of 0.11 ± 0.01 nM in these cells. LSD, like quinpirole, acts as full agonist (Fig. 7), dose-dependently inhibiting forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. LSD is more potent than ABT-724, which shows only partial agonist activity at the D4 receptor. We reported earlier (Chemel et al. 2006a) that WAY 100635 behaves as a full agonist at human D4.4 receptors stably expressed in HEK cells, with efficacy and affinity comparable to quinpirole. In contrast to LSD, the hallucinogenic amphetamine derivative DOI had no detectable affinity at the D4.4 receptor. For the D4 receptor antagonists used in the drug discrimination experiments, the most potent is L-745,870, showing more than an order of magnitude higher affinity for the D4.4 receptor than the atypical antipsychotic drug clozapine.

Dose–response curves for D4.4 receptor-mediated inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation. HEK-hD4.4 cells were incubated with 5 μM forskolin (FSK) in the presence of increasing concentrations of the indicated agonists for 15 min at 37°C. Experiments were performed in duplicate. Data from each assay were normalized to percent of maximum cAMP accumulation stimulated by forskolin, as estimated from the upper limits of dose–response curves generated by GraphPad Prism. Data points represent mean ± SEM of combined data from at least four experiments

Discussion

Our main finding is that stimulation or inhibition of the dopamine D4 receptor has a significant modulatory effect on the discriminative stimulus properties of LSD, but not the discriminative stimulus effect produced by the hallucinogenic phenethylamine DOI. The role of the D4 receptor is most pronounced in the later temporal effects of LSD (in LSD-90 rats). Our earlier results had provided evidence that the delayed temporal phase in the behavioral pharmacology of LSD is mediated by D2-like dopamine receptor activation (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005, Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 2007), and results from this study identify the D4 receptor as the relevant D2-like isoform.

Thus, we evaluated the effect of stimulation or inhibition of dopamine D4 receptors on 5HT2A (DOI and LSD-30) or D2-like (LSD-90)-mediated discriminative stimulus effects. We demonstrate that the interoceptive cue of LSD, when given 90 min before training, is mediated through activation of dopamine D4 receptors. Consistent with that conclusion, the selective dopamine D4 receptor antagonists L-745,870 and A-381393 significantly attenuated the LSD-90 cue to a somewhat greater extent than LSD-30 responding and had no effect on the DOI cue. The D4 dopamine full agonist WAY 100635 mimics the LSD-90 cue, produces only partial substitution in LSD-30 rats, and only saline-appropriate responding in DOI-trained rats. Finally, the partial D4 agonist ABT-724 produced no substitution in DOI-trained rats, a bell-shaped dose–response curve in LSD-30 rats, and partial substitution in LSD-90 trained rats.

WAY 100635 has highest affinity for the 5-HT1A receptor (Fletcher et al. 1996; Forster et al. 1995) and for more than a decade has been widely used as the selective antagonist of choice for this receptor. Although WAY 100635 has tenfold higher affinity for the 5-HT1A than for the D4 receptor (Chemel et al. 2006a), at higher doses, it induces behavioral effects mediated by D4 receptor activation (Chemel et al. 2006b). Although Martel et al. (2007) have recently suggested that WAY 100635 is only a very weak partial D4 agonist with greater than 200-fold selectivity for the 5-HT1A receptor, our behavioral results are not consistent with that characterization and are more in line with our earlier report that the selectivity at the 5-HT1A receptor versus the D4 dopamine receptor is only about ten-fold (Chemel et al. 2006a). Low doses of WAY 100635 did not produce a discriminative stimulus effect in rats, as rats were unable to discriminate between WAY 100635 and saline. By contrast, at higher doses, WAY 100635 generates a discriminative stimulus that is not mimicked by other 5-HT1A antagonists, is blocked by D4 antagonists, and is not reversed by co-administration of 5-HT1A agonists (unpublished). It also has been proposed that 5-HT1A receptor agonists are able to modulate the discriminative stimulus effects of LSD given at short times before testing (Reissig et al. 2005). Consistent with all these findings, in the present study, low doses of WAY 100635 were able to attenuate partially the LSD-30 cue, but not the DOI cue.

In the combination tests, we have clearly demonstrated that co-administration of LSD with either a low or high dose of WAY 100635 has divergent effects. Pretreatment with 0.4 mg/kg of WAY 100635 flattened the LSD dose–response curve in the LSD-30 group by partially attenuating drug-appropriate responding, most notably at higher doses of LSD. A similar but less marked effect was observed with the LSD-90 cue, whereas the low dose of WAY 100635 had no effect on the DOI cue. It therefore seems reasonable to speculate that the effect of the low dose of WAY on the LSD cue is mediated by its 5-HT1A receptor antagonism.

Although conflicting results have emerged from a variety of behavioral paradigms employed to study interactions between 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, Reissig et al. (2005) have reported that in their drug discrimination studies, 5-HT1A receptor agonists enhanced the discriminative stimulus effects of LSD and 5-HT1A antagonists attenuated it. Recently, Reissig et al. (2008) have reported that antagonism of the 5-HT2A receptor attenuated a 5-HT1A-mediated drug discrimination cue, and the authors suggested that in drug discrimination studies, the interaction between 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors is bidirectional. In our laboratory, we were never able to potentiate the LSD cue by co-administration of a 5-HT1A agonist (unpublished results) because this combination induces a serotonin syndrome that interferes with lever responding, leading to behavioral disruption in our FR50 paradigm.

In combination tests with the D4 partial agonist ABT 724, we observed enhancement of the discriminative stimulus effect of LSD-30 only at low doses, but robust potentiation of the LSD cue in LSD-90 rats. Combination of 10 μmol/kg of WAY 100635 with LSD or DOI resulted in leftward shifts of the dose–response curves quite markedly in LSD-90 rats and less so in LSD-30- and DOI-trained rats. We believe that the high degree of potentiation observed in LSD-90-trained rats occurs because the primary mechanism responsible for the discriminative stimulus effects in these rats occurs through stimulation of D2-like receptors (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005), the dopamine D4 receptor being a member of the D2 receptor family.

A different mechanism is likely responsible for enhancement of the 5-HT2A-mediated cue. It is possible that stimulation of D4 dopamine receptors potentiates the function of 5-HT2A receptors. The dopamine D4 receptor mediates changes in neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity in the brain (Rubinstein et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2002, 2003) and is thought to play a major role in the control of integrative functions underlying the organization of complex behavior (Fuster 2001). Dopamine D4 receptors are localized on cortical pyramidal neurons, with particularly high expression in the anterior cingulate as well as on GABAergic interneurons throughout the frontal cortex (Mrzljak et al. 1996; Wedzony et al. 2000); some cortical GABAergic interneurons also express 5-HT2A receptors (Griffiths and Lovick 2002; de Almeida and Mengod 2007). D4 receptor activation attenuates both GABA-mediated inhibition of medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons and N-methyl-d-aspartic-acid-mediated synaptic responses (Seamans et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2002, 2003). Another mechanism for 5-HT2A interactions with dopaminergic systems that has been proposed includes the possibility that 5-HT2A receptors might act as presynaptic heteroreceptors on dopamine axon terminals (Pehek 1996; Pehek et al. 2001), a hypothesis that finds support in the study by Miner et al. (2003), showing that in the prefrontal complex (PFC), some 5-HT2A receptors are localized on dopaminergic terminals. Thus, dopamine D4 receptors are co-localized in some of the same cortical layers where 5-HT2A receptors are highly expressed and might directly or indirectly modulate 5-HT2A receptor function.

Dopamine D4 receptor stimulation can activate multiple intracellular pathways, including inhibition of cAMP synthesis (Seamans and Yang 2004) and modulation of G-protein-regulated ion channels (Pillai et al. 1998; Wedemeyer et al. 2007). Moreover, one of the important targets of dopamine D4 receptors is calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), which distinguishes D4 receptor signaling from dopamine D2 signaling (Wang et al. 2003; Gu and Yan 2004; Gu et al 2006). In PFC neurons, D4 receptor stimulation increases CaMKII activity through phospholipase C (PLC)/inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3)-receptor-dependent pathways, resulting in elevation of intracellular Ca2+. This effect is similar to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores through activation of Gq-coupled receptors, the family to which the 5-HT2A receptor belongs. Thus, D4 receptor activation might enhance 5-HT2A-mediated effects through the PLC/IP3 pathway.

It is well known that atypical antipsychotics, such as clozapine and olanzapine, have high affinities for the 5-HT2A and dopamine D2 and D4 receptors (Roth et al. 1995; Meltzer 1999; Seeman et al. 1997; Richelson and Souder 2000). We examined the ability of these drugs to affect the DOI, LSD-30, and LSD-90 cues, assuming that the antagonistic promiscuity of these antipsychotics might be important to explain differences between mechanisms responsible for blockade of discriminative stimulus effects. Both clozapine and olanzapine partially inhibited the DOI cue, and we hypothesize that the antagonist properties of clozapine and olanzapine at the 5-HT2A receptor are responsible for inhibition of the DOI cue, whereas their D2 and D4 antagonism is responsible for the marked behavior disruption observed during these combination tests. In LSD-30- and LSD-90-trained rats, clozapine and olanzapine produced dose-dependent full inhibition with limited behavioral disruption in LSD-30 rats and no disruption in LSD-90 rats. We call attention to the very high potency of clozapine in blocking the LSD-90 cue and note that clozapine is considered to be one of the most efficacious atypical antipsychotics.

In our previous paper (Marona-Lewicka et al. 2005), we showed that MDL 100907, a selective 5-HT2A antagonist, produced some degree of LSD-90 cue inhibition, and haloperidol, a nonselective dopamine receptor antagonist, also slightly attenuated drug-appropriate lever selection in LSD-30 rats. Thus, we conclude that although activation of 5-HT2A receptors plays a central role in the discriminative stimulus effects in LSD-30 rats, a minor dopaminergic pharmacology component is also probably involved. By contrast, D2-like receptor activation, presumably the D4 receptor, is the central element in the LSD-90 discriminative stimulus, but the 5-HT2A receptor also must play some role. As was noted earlier, pretreatment with 5-HT2A agonists can dramatically potentiate the discriminative stimulus effects of amphetamine (Marona-Lewicka and Nichols 1997) and methamphetamine (Munzar et al. 1999, 2002) and slightly enhances the cocaine cue (Munzar et al. 2002) in rats. If activation of 5-HT2A receptors serves to sensitize the dopamine system, it seems possible that the 5-HT2A agonist effect of LSD is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the strength of the LSD-90 cue.

In summary, the results presented here suggest that the dopamine D4 receptor plays a modulatory role in the discriminative stimulus effects produced by LSD, a drug with complex pharmacological properties. We also show that manipulation of D4 dopamine receptors has a much more marked effect on the discriminative cue generated during the later temporal phase of LSD action than for discriminative stimulus effects occurring 15–30 min after LSD administration. No similar role of the D4 receptor was evident for the hallucinogenic amphetamine DOI, which possesses affinity only at the 5-HT2 family receptors. The involvement of both dopamine and serotonin pathways in the pharmacology of LSD, but not DOI, is very intriguing given the vast body of research demonstrating that LSD is a more potent hallucinogen than phenethylamines, even though their affinities at the 5-HT2A receptor are not significantly different, with the intrinsic activity of LSD actually being lower than DOI at these receptors (Nichols 2004).

References

Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ (2000) Serotonin model of schizophrenia: emerging role of glutamate mechanisms. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 31:302–312

Alex KD, Pehek EA (2007) Pharmacologic mechanisms of serotonergic regulation of dopamine neurotransmission. Pharmacol Ther 113:296–320

Bortolozzi A, az-Mataix L, Scorza MC, Celada P, Artigas F (2005) The activation of 5-HT receptors in prefrontal cortex enhances dopaminergic activity. J Neurochem 95:1597–1607

Brioni JD, Moreland RB, Cowart M, Hsieh GC, Stewart AO, Hedlund P, Donnelly-Roberts DL, Nakane M, Lynch JJ, Kolasa T, Polakowski JS, Osinski MA, Marsh K, Andersson K-E, Sullivan JP (2004) Activation of dopamine D4 receptors by ABT-724 induces penile erection in rats. Proc Nat Acad Sci 101:6758–6763

Chemel BR, Roth BL, Armbruster B, Watts VJ, Nichols DE (2006a) WAY-100635 is a potent dopamine D4 receptor agonist. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 188:244–251

Chemel BR, Roth BL, Armbruster B, Watts VJ, Marona-Lewicka D, Nichols DE (2006b) The “selective” 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100635 and its metabolite WAY-100634, are potent dopamine D4 receptor agonists. ACNP, 45th Annual Meeting, Hollywood, FL

Cheng Y, Prusoff WH (1973) Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol 22:3099–3108

Colpaert FC, Niemegeers CJ, Janssen PA (1982) A drug discrimination analysis of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): in vivo agonist and antagonist effects of purported 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonists and of pirenperone, a LSD-antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 221:206–214

Cowart M, Latshaw SP, Bhatia P, Daanen JF, Rohde J, Nelson SL, Patel M, Kolasa T, Nakane M, Uchic ME, Miller LN, Terranova MA, Chang R, Donnelly-Roberts DL, Namovic MT, Hollingsworth PR, Martino BR, Lynch JJ III, Sullivan JP, Hsieh GC, Moreland RB, Brioni JD, Stewart AO (2004) Discovery of 2-(4-pyridin-2-ylpiperazin-1-ylmethyl)-1H-benzimidazole (ABT-724), a dopaminergic agent with a novel mode of action for the potential treatment of erectile dysfunction. J Med Chem. 47:3853–3864

de Almeida J, Mengod G (2007) Quantitative analysis of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons expressing 5-HT(2A) receptors in human and monkey prefrontal cortex. J Neurochem 103:475–486

Fletcher A, Forster EA, Bill DJ, Brown G, Cliffe IA, Hartley JE, Jones DE, McLenachan A, Stanhope KJ, Critchley DJ, Childs KJ, Middlefell VC, Lanfumey L, Corradetti R, Laporte AM, Gozlan H, Hamon M, Dourish CT (1996) Electrophysiological, biochemical, neurohormonal and behavioural studies with WAY-100635, a potent, selective and silent 5-HT1A receptor antagonist. Behav Brain Res 73:337–353

Forster EA, Cliffe IA, Bill DJ, Dover GM, Jones D, Reilly Y, Fletcher A (1995) A pharmacological profile of the selective silent 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY-100635. Eur J Pharmacol 281:81–88

Freedman DX (1984) LSD: The bridge from human to animal. In: Jacobs BL (ed) Hallucinogens: neurochemical, behavioral, and clinical perspectives. Raven, New York, pp 203–226

Fuster JM (2001) The prefrontal cortex—an update: time is of the essence. Neuron 30:319–333

Glennon RA (1986) Discriminative stimulus properties of the serotonergic agent 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane (DOI). Life Sci 39:825–830

Glennon RA, Titeler M, McKenney JD (1984) Evidence for 5-HT2 involvement in the mechanism of action of hallucinogenic agents. Life Sci 35:2505–2511

Griffiths JL, Lovick TA (2002) Co-localization of 5-HT 2A -receptor- and GABA-immunoreactivity in neurones in the periaqueductal grey matter of the rat. Neurosci Lett 326:151–154

Gu Z, Yan Z (2004) Biodirectional regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity by dopamine D4 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Mol Pharmacol 66:948–955

Gu Z, Jiang Q, Yuen EY, Yan Z (2006) Activation of dopamine D4 receptors induces synaptic translocation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in cultured prefrontal cortical neurons. Mol Pharmacol 69:813–822

Ichikawa J, Meltzer HY (1995) DOI, a 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist, potentiates amphetamine-induced dopamine release in rat striatum. Brain Res 698:204–208

Klodzinska A, Chojnacka-Wojcik E (1997) Involvement of 5-HT2A receptors in mediating of the discriminative stimulus properties of DOI in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 7:S273

Litchfield JT Jr, Wilcoxon F (1949) A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 96:99–112

Lucas G, Spampinato U (2000) Role of striatal serotonin2A and serotonin2C receptor subtypes in the control of in vivo dopamine outflow in the rat striatum. J Neurochem 74:693–701

Marona-Lewicka D, Nichols DE (1994) Behavioral effects of the highly selective serotonin releasing agent 5-methoxy-6-methyl-2-aminoindan. Eur J Pharmacol 258:1–13

Marona-Lewicka D, Nichols DE (1997) 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonists potentiate the discriminative cue of (+)-amphetamine in the rat. Neuropharmacology 36:1471–1475

Marona-Lewicka D, Nichols DE (2007) Further evidence that the delayed temporal dopaminergic effects of LSD are mediated by a mechanism different than the first temporal phase of action. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 87:453–461

Marona-Lewicka D, Thisted RA, Nichols DE (2005) Distinct temporal phases in the behavioral pharmacology of LSD: dopamine D2 receptor-mediated effects in the rat and implications for psychosis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 180:427–435

Martel J-C, Leduc N, Ormiere A-M, Foucillon V, Danty N, Culie C, Cussac D, Newman-Tancredi A (2007) WAY-100635 has high selectivity for serotonin 5-HT1A versus dopamine D4 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 574:15–19

Meltzer HY (1999) The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology 21:106S–115S

Miner LA, Backstrom JR, Sanders-Bush E, Sesack SR (2003) Ultrastructural localization of serotonin2A receptors in the middle layers of the rat prelimbic prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 116:107–117

Mrzljak L, Bergson C, Pappy M, Huff R, Levenson R, Goldman-Rakic PS (1996) Localization of dopamine D4 receptors in GABAergic neurons of the primate brain. Nature 381:245–248

Munzar P, Laufert MD, Kutkat SW, Novakova J, Goldbertg SR (1999) Effects of various serotonin agonists, antagonists, and uptake inhibitors on the discriminative stimulus effects of methamphetamine in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291:239–250

Munzar P, Justinova Z, Kutkat SW, Goldberg SR (2002) Differential involvement of 5-HT2A receptors in the discriminative-stimulus effects of cocaine and methamphetamine. Eur J Pharmacol 436:75–82

Nakane M, Cowart MD, Hsieh GC, Miller L, Uchic ME, Chang R, Terranova MA, Donnelly-Roberts DL, Namovic MT, Miller TR, Wetter JM, Marsh K, Stewart AO, Brioni JD, Moreland RB (2005) 2-[4-(3,4-Dimethylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylmethyl]-1H benzoimidazole (A-381393), a selective dopamine D4 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology 49:112–121

Newman-Tancredi A, Audinot V, Chaput C, Verriele L, Millan MJ (1997) [35S]Guanosine-5¢-O-(3-thio)triphosphate binding as a measure of efficacy at human recombinant dopamine D4.4 receptors: actions of antiparkinsonian and antipsychotic agents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282:181–191

Nichols DE (2004) Hallucinogens. Pharmacol Ther 101:131–181

Patel S, Freedman S, Chapman KL, Emms F, Fletcher AE, Knowles M, Marwood R, McAllister G, Myers J, Curtis N, Kulagowski JJ, Leeson PD, Ridgill M, Graham M, Matheson S, Rathbone D, Watt AP, Bristow LJ, Rupniak NM, Baskin E, Lynch JJ, Ragan CI (1997) Biological profile of L-745,870, a selective antagonist with high affinity for the dopamine D4 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283:636–647

Pehek EA (1996) Local infusion of the serotonin antagonists ritanserin or ICS 205,930 increases in vivo dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Synapse 24:12–18

Pehek EA, McFarlane HG, Maguschak K, Price B, Pluto CP (2001) M100,907, a selective 5-HT(2A) antagonist, attenuates dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Res 888:51–59

Pehek EA, Nocjar C, Roth BL, Byrd TA, Mabrouk OS (2006) Evidence for the preferential involvement of 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in stress- and drug-induced dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:265–277

Pillai G, Brown NA, McAllister G, Milligan G, Seabrook GR (1998) Human D2 and D4 dopamine receptors couple through betagamma G-protein subunits to inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK1) in a Xenopus oocyte expression system: selective antagonism by L-741,626 and L-745,870 respectively. Neuropharmacol 37:983–987

Reissig CJ, Eckler JR, Rabin RA, Winter JC (2005) The 5-HT1A receptor and the stimulus effects of LSD in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 182:197–204

Reissig CJ, Eckler JR, Rabin RA, Rice KC, Winter JC (2008) The stimulus effects of 8-OH-DPAT: Evidence for a 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated component. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 88:312–317

Richelson E, Souder T (2000) Binding of antipsychotic drugs to human brain receptors. Focus on newer generation compounds. Life Sci 68:29–39

Roth BL, Tandra S, Burgess LH, Sibley DR, Meltzer HY (1995) D4 dopamine receptor binding affinity does not distinguish between typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 120:365–368

Rubinstein M, Cepeda C, Hurst RS, Flores-Hernandez J, Ariano MA, Falzone TL, Kozell LB, Meshul CK, Bunzow JR, Low MJ, Levine MS, Grandy DK (2001) Dopamine D4 receptor-deficient mice display cortical hyperexcitability. J Neurosci 21:3756–3763

Seamans JK, Yang CR (2004) The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neurobiol 74:1–58

Seamans JK, Gorelova N, Durstewitz D, Yang CR (2001) Bidirectional dopamine modulation of GABAergic inhibition in prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 21:3628–3638

Seeman P, Corbett R, Van Tol HHM (1997) Atypical neuroleptics have low affinity for dopamine D2 receptors or are selective for D4 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 16:93–110

Smith RL, Barrett RJ, Sanders-Bush E (1999) Mechanism of tolerance development to 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine in rats: down-regulation of the 5-HT2A, but not 5-HT2C, receptor. Psychopharmacology 144:248–254

Van Tol HH, Bunzow JR, Guan HC, Sunahara RK, Seeman P, Niznik HB, Civelli O (1991) Cloning of the gene for a human dopamine D4 receptor with high affinity for the antipsychotic clozapine. Nature 350:610–614

Vollenweider FX, Vontobel P, Hell D, Leenders KL (1999) 5-HT modulation of dopamine release in basal ganglia in psilocybin-induced psychosis in man - A PET study with [11C]raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology 20:424–433

Wang X, Zhong P, Yan Z (2002) Dopamine D4 receptors modulate GABAergic signaling in pyramidal neurons of prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 22:9185–9193

Wang X, Zhong P, Gu Z, Yan Z (2003) Regulation of NMDA receptors by dopamine D4 signaling in prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 23:9852–9861

Watts VJ, Neve KA (1996) Sensitization of endogenous and recombinant adenylate cyclase by activation of D2 dopamine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 50:966–976

Watts VJ, Lawler CP, Fox DR, Neve KA, Nichols DE, Mailman RB (1995) LSD and structural analogs: pharmacological evaluation at D1 dopamine receptors. Psychopharmacology 118:401–409

Watts VJ, Vu MN, Wiens BL, Jovanovic V, Van Tol HH, Neve KA (1999) Short- and long-term heterologous sensitization of adenylate cyclase by D4 dopamine receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 141:83–92

Wedemeyer C, Goutman JD, Avale ME, Franchini LF, Rubinstein M, Calvo DJ (2007) Functional activation by central monoamines of human dopamine D(4) receptor polymorphic variants coupled to GIRK channels in Xenopus oocytes. Eur Pharmacol 562:165–173

Wedzony K, Chocyk A, Mackowiak M, Fijal K, Czyrak A (2000) Cortical localization of dopamine D4 receptors in the rat brain—immunocytochemical study. J Physiol Pharmacol 51:205–221

Winter JC, Fiorella DJ, Timineri DM, Filipink RA, Helsley SE, Rabin RA (1999) Serotonergic receptor subtypes and hallucinogen-induced stimulus control. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64:283–293

Xu T, Pandey SC (2000) Cellular localization of serotonin(2A) (5HT(2A)) receptors in the rat brain. Brain Res Bull 51:499–505

Yan QS (2000) Activation of 5-HT2A/2C receptors within the nucleus accumbens increases local dopaminergic transmission. Brain Res Bull 51:75–81

Zar J (1999) Biostatistical analysis, 4th edn, (Section 24.6). Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, pp 533–538

Zhuang ZP, Kung MP, Kung HF (1994) Synthesis and evaluation of 4-(2'methoxyphenyl)-1-(2'-[N-(2"-pyridinyl)-p-iodobenzamid]ethyl)piperazine (p-MPPI): a new radioiodinated 5-HT1A ligand. J Med Chem 37:1406–1407

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marona-Lewicka, D., Chemel, B.R. & Nichols, D.E. Dopamine D4 receptor involvement in the discriminative stimulus effects in rats of LSD, but not the phenethylamine hallucinogen DOI. Psychopharmacology 203, 265–277 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1238-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1238-0