Abstract

Summary

Secondary-level healthcare professionals, mainly rheumatologists and orthopedic surgeons, were invited to participate in an online survey questionnaire to assess knowledge and compliance with osteoporosis management guidelines and strategies, as well as self-reported quality of care. About 51% of the participants admit that they do not implement specific guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in their standard practice and depend on their experience and their clinical judgments. Moreover, although a good percentage (58%) had satisfactory knowledge levels in domains on the risk of osteoporotic fractures and investigations of osteoporosis, 47.5% of the participants did not score satisfactorily in questions on pharmacotherapy, especially for those patients at high risk for fractures.

Introduction

A recently published study demonstrated a treatment gap among those eligible for osteoporosis therapy in Egypt of about 82.1% in postmenopausal women and 100% in men. The current survey aimed to address some of the factors that may contribute to this wide gap.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of secondary care healthcare professionals (both physicians and orthopedic surgeons) who were invited to complete an online questionnaire, which gathered information about physicians’ socio-demographic data, knowledge, and compliance with osteoporosis management guidelines and strategies, as well as self-reported quality of care. Additionally, a knowledge score was calculated for all the participants.

Results

A good percentage (58%) had a satisfactory knowledge level in domains on the risk of osteoporotic fractures and investigations of osteoporosis; however, 47.5% did not score satisfactorily in questions on pharmacotherapy, especially for those patients at high risk for fractures.

Conclusions

This work has identified some of the barriers to implementing guidelines for osteoporosis and fragility fracture management. In the meantime, it highlights the urgency of intensifying efforts to develop the knowledge and attitude of the healthcare professionals dealing with this condition in Egypt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinical practice guidelines for osteoporosis management offer a concise strategy for healthcare professionals (HCPs) to streamline the delivery of care according to the best available evidence combined with the patient’s and family’s preferences and values as well as their professional judgment [1]. Guidelines are considered a pivotal resource to set up, deliver, assess, and adjust the quality of healthcare provided to patients [2]. Unfortunately, the approaches commonly implemented to adopt guidelines in day-to-day practice have an inconsistent and modest impact [3]. This has been compounded by reports of overuse or underuse of the guidelines [4,5,6]. These factors highlighted the importance of enhancing the application of guidelines in standard practice. In turn, this would capitalize on the substantial investment offered by the healthcare organizations to develop the guidelines and improve the quality of care provided to patients.

Despite significant advances in the epidemiology, pathophysiology, risk assessment, and management of osteoporosis over the last few decades, there is evidence that osteoporosis is underdiagnosed and undertreated worldwide [7, 8]. In concordance, in Egypt and the Arab world, there is a substantial proportion of women and men who remain untreated and are therefore at high risk of sustaining fragility fractures. This represents a treatment gap that has been reported in secondary fracture prevention in both public and private settings [9]. With the growing number of elderly people, the coming decades will witness a dramatic increase in the number of older adults living with osteoporosis and experiencing morbidity(ies) subsequent to fragility fractures [10].

Surveys are commonly used to recognize hurdles in guideline implementation [11,12,13]. Surveys can be accessed by a broad and diverse spectrum of guideline users. The facility of online administration of such surveys is an advantage, as it represents an economical means of data collection. The studies carried out by Baker et al. [11] and Krause et al. [12] revealed that physicians are the most common target of barrier surveys. At present, limited information is available on osteoporosis knowledge, attitude, and practice among the healthcare professionals dealing with osteoporotic patients in Egypt. Therefore, this work was carried out with the aim of assessing the current knowledge and quality of care of the healthcare professionals (whether physicians or surgeons) looking after older adults who sustained fragility fractures. This is expected to identify practice gaps that could be acted upon to improve osteoporosis care. Identifying these gaps would help in formulating recommendations for policymakers to prioritize osteoporosis care on the national level.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study of secondary care healthcare professionals (both physicians and orthopedic surgeons) who were invited to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed following a scoping review and was based on the Egyptian guidelines for osteoporosis management [14]. A self-administered online questionnaire was made available online through Survey Monkey. The link was sent electronically to 225 Egyptian secondary healthcare professionals concerned with osteoporosis management, mainly rheumatologists and orthopedic surgeons. The questionnaire development was based on theory and a review of the literature according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria [15] (supplement 1).

The questionnaire

A self-administered online questionnaire was made available online through Survey Monkey and is composed of three main domains. The first domain is “Self-reported professional practice data,” which includes information about healthcare professionals’ socio-demographic and professional characteristics, including location (governorate), current employment, speciality, and years of practice. The second domain is “knowledge and compliance with osteoporosis management guidelines and strategies.” This includes 22 questions that cover 4 subdomains to assess the participant’s knowledge about: (1) osteoporosis management guidelines (6 questions), (2) osteoporosis management strategies (10 questions), (3) the FRAX fracture assessment tool (4 questions), and (4) FLS (fracture liaison services) (2 questions). The third domain consists of four questions that assess “self-reported quality of care.” In total, the questionnaire includes 30 questions presented as multiple-choice answers. The participants were asked to choose the item that reflected their extent of agreement on each question (Supplement 2).

To compare the test against its goals and theoretical properties, the face and content validity of the questionnaire were established by two experts in osteoporosis based on a conceptual framework. A pilot test among 10 healthcare professionals was carried out to assess the items, ease, and flow of understanding the questionnaire.

A scoring system was constructed, starting with question “11” and the subsequent 19 questions. The score of each question ranged from 0 to 5. A total score of 75–100 was classified as good knowledge, compliance, and quality of care in osteoporosis management. Scores from 50 to 74 were identified as average, and scores less than 50 signified poor knowledge, compliance, and quality of care.

Sample size

Based on a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, and a population size of 100, the ideal sample size was calculated using the online sample size calculator (https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/calculating-sample-size/). The ideal sample size was 80. Finally, 128 participants were recruited for our study.

Ethical approval

All procedures carried out in this work were according to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, as well as its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The ethical board exempted the study from ethical approval as it involved only healthcare professionals. Nonetheless, participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Study population

The questionnaire was completed by physicians, mainly rheumatologists, as well as orthopedic surgeons who are actively managing osteoporosis in their standard practice. 21 centers across the country were invited. The invited healthcare professionals were at different levels of seniority. The questionnaire was completed anonymously and without compensation. No patients were involved in this research at any stage.

Statistical analysis

Data were fed to the computer and analyzed using IBM SPSS software package version 20.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Categorical data were represented as numbers and percentages. The chi-square test was applied to compare two groups. Alternatively, the Monte Carlo correction test was applied when more than 20% of the cells had an expected count less than 5. For continuous data, they were tested for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative data were expressed as range (minimum and maximum), mean, standard deviation, and median. Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two groups for not normally distributed quantitative variables. On the other hand Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare more than two studied categories for not normally distributed quantitative variables. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

Results

Out of 225 HCP invited to participate in the survey, only 128 responded (a response rate of 56.8%). There were no missing values in the collected data.

Self-reported professional practice data

The majority of the participants (76%) were from urban areas, whereas 24% were from rural areas (Q1). Regarding current employment (Q2), 66% were working in University Hospitals, 25% in ministry of health, 4.7% in health insurance hospitals, and less than 4% were working in private clinics. Considering the specialty (Q3), 73.4% were rheumatologists, while the orthopedic surgeons were about 22%. Other specialties, including neurosurgeons, endocrinologists, and gynecologists, constituted less than 5%. Seniors with more than 10 years’ experience constituted 60% of the participants, whereas young physicians with 1–3 years’ experience were only 19.5% of the participants. 11.7% have 5 to 10 years of experience, and 8.6% have 3–5 years of experience (Q4) (Table 1).

Physicians’ knowledge and compliance with osteoporosis management guidelines

Considering the participants’ training (Q5), 66.4% of the participants agreed that they were adequately trained to access and apply guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in their daily practice. In contrast, 17% disagreed, and 16.4% were neither agreeing nor disagreeing. When asked about their adherence to management guidelines (Q6), 38% rated their adherence to osteoporosis management guidelines as high, while nearly half of the participants (49%) described their adherence as average. On the other hand, 12.5% admit that their adherence is low.

When asked about the national guidelines for the management of osteoporosis (Q7 and 8), 56.3% of the participants answered that they did not read or implement the national guidelines. Considering the alternatives (Q9), the majority of the participants (63.3%) preferred to follow the international guidelines for management of osteoporosis, such as those of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), the American College of Physician (ACP), or the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). However, regarding day-to-day practice (Q10), about 51% of the participants did not implement specific guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in their standard practice and relied on their experience and their clinical judgments (Table 2).

Physicians’ knowledge and compliance with osteoporosis management strategies

When asked about their attitude toward laboratory testing (Q11), 46% of the participants stated that they always check for serum calcium and vitamin D in patients with high risk of osteoporosis, while about 30% answered “usually,” 18% “sometimes,” and about 5.5% ticked “not necessary.” Similarly, when they asked about prescribing calcium and vitamin D supplements (Q12), about 41% answered “always,” while 40% and 20% answered “usually,” and “sometimes” consecutively (Table 2).

The value of exercise programs in the elderly population for the preservation of their bone and muscle health was an important issue to be addressed in this survey (Q13). About 55% of the participants stated that they always prescribe exercise programs for patients in the geriatric age group. 27% answered with “usually,” 12.5% said “sometimes,” and less than 5% found it not necessary.

The participants were asked whether they inquired about the mechanism of injury and how the patient sustained the fragility fracture (Q14). The majority (73%) answered “always,” whereas when asked about the possibility of imminent fracture risk (Q15), 79.5% stated that they always ask about the history of fragility fracture. Most of the participants (80%) used to ask for DXA scans after fragility fractures (Q16).

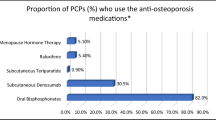

Regarding the prescription of osteoporotic medications after fragility fractures (Q17), 55% of the participants answered that they prescribe them for all patients, while 37.6% prescribe them for some of the patients, and 7.2%, mostly the orthopedic surgeons, are rarely or not concerned with osteoporosis management. Although early start of osteoporotic medications after fragility fracture is essential to prevent subsequent fractures (Q18), only 50% of the participants agreed to start immediately after fracture, whereas 32% stated they feel more comfortable starting 1-month post-fracture, while 18.4% opted for waiting until complete fracture healing, which was mainly evident among the orthopedic surgeons.

Assessment of falls risk (Q19) is used to be done by the majority of the participants (81.0%), whereas nearly all the orthopedic surgeons were not concerned with fall risk assessment. Follow-up of the patients for prevention of future fracture (Q20) is always done by 33% of the HCP, while 41.7% answered “usually,” and 8% of the participants were not concerned with follow-up of their patients. The answers summarizing the physicians’ knowledge and compliance with osteoporosis management strategies are shown in Table 2.

Physicians’ knowledge with the FRAX fracture assessment tool and FLS

85.6% of the participants were familiar with the FRAX fracture assessment tool (Q21); however, 32% were not aware of the role of FRAX in osteoporosis management (Q22). Thirty seven percent (39%) of the HCP who participated in our survey were not interested in the FRAX tool, and only about 15% knew that it was designed for males and females above 40 (Q23). The cutoff value of FRAX to start osteoporotic medication was only known for 21.8% of the participants (Q24).

Regarding FLS, only 36% were aware of FLS services in their areas, 24% heard about them, but were unaware of their actual role in osteoporosis management, and 39% were not familiar with nearby FLS services (Q25). This was linked to Q26, which revealed that about half of the participants preferred to prescribe osteoporosis medication rather than referring cases with fragility fractures to the nearby FLS center, especially the orthopedic surgeons. The answers summarizing the physicians’ knowledge of the FRAX fracture assessment tool and FLS are shown in Table 3.

Healthcare professionals’ self-reported quality of care

Although the cutoff value for FRAX was only known to 21.8% of the participants, 41.4% stated that in patients with low impact fractures, they rely on DXA and the FRAX tool to decide their management plan, whereas 42% still depend on the DXA scan alone. On the other hand, the FRAX tool alone was important to about 8% of the participants, and 8.6% were not concerned with osteoporosis management after low impact fractures (Q27).

To decide which interventional threshold is used to determine commencing osteoporosis therapy (Q28), DXA scan was the most commonly used investigation tool (43%), whereas 31% preferred to calculate the FRAX score in addition to measuring the bone mineral density by DXA scan.

Managing osteopenic patients with low impact fractures was debated among the participants (Q29); 51% stated that they calculate the FRAX score to decide their management plan, while 42% answered that they used to prescribe only calcium and vitamin D supplements, and 7% were convinced that there is no need for medications as long as the patient is not osteoporotic.

Fragility fractures that take place while the patients are on osteoporotic medications were another pivotal point to consider (Q30). About 19% of the participants were convinced that they had to stop the medications until complete fracture healing, while 37% preferred to continue with the same medications despite treating very high-risk patients, but the majority (44%) answered that they had to shift to another medication. The answers summarizing the physicians’ self- reported quality of care are shown in Table 4.

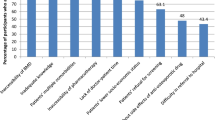

Distribution of the HCP according to total knowledge and compliance score

About 58% of the participants were classified as having an average score (mean 68 ± 13.5) regarding knowledge and compliance with guidelines and strategies of osteoporosis management, as well as self-reported quality of care. Only 31% gained a high score, and about 11% had a low score (Fig. 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the total score of HCP in urban and rural areas. The total score of the HCP working in university hospitals was statistically higher than that of those working in ministry of health and health insurance hospitals (P = 0.011*). Additionally, the scoring of the orthopedic surgeons was significantly lower than that of the rheumatologists (61.9 ± 13.5 versus 70 ± 13, P = 0.008*). Lastly, no statistically significant difference was noticed regarding the scoring of the participating HCPs with different years of experience (Table 5).

Discussion

The Egyptian healthcare system is pluralistic, comprising a variety of healthcare providers from the public as well as the private sector. Although university hospitals, ministry of health, and military hospitals offer primary care, patients prefer to see secondary care specialists directly [14]. Osteoporosis management is provided mostly by rheumatologists with a special interest in metabolic bone diseases and, to a lesser extent, orthopedic surgery. In 2021, the Egyptian consensus on treat-to-target approach for osteoporosis was published, giving national guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in both men and women [10]. This coincided with the launch of the fracture liaison service (FLS) which included 14 FLS centers recognized by the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and covered nearly 71.8% of the Egyptian population. The FLS network is moderated by the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health. Electronic national register was launched at the same year together with the national clinical standards for fracture liaison service in Egypt were published later [16]. The FLS centers coordinate with the orthopedic surgery regarding management of patients admitted or reviewed in the accident and emergency for fragility fractures (including both major osteoporosis fractures as well as hip fractures). In 2023, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) awarded one FLS center in Egypt a gold star, whereas two other centers were awarded a silver star (https://www.capturethefracture.org/map-of-best-practice).

This study was carried out to identify the potential barriers to implementing the osteoporosis guidelines in standard practice by the specialized healthcare professionals who are in charge of the management and monitoring of osteoporosis and its associated fragility fractures. All the representatives of the wider clinician community responsible for bone health care and osteoporosis were approached through the university groups as well as regional leagues covering all of the country. Such approach has been reported to be essential for planning the process of guideline implementation [11]. The developed questionnaire probed the full range of barrier domains and subdomains that have been identified as potential difficulties in the guidelines’ implementation. The questionnaire focused on individual health professional barriers and was based mainly on multiple types of response options, which is the most common approach adopted in similar studies [2]. The questionnaire was assessed for its psychometric properties before use and was pilot tested among a sample of healthcare professionals’ guideline users.

Lack of knowledge has been suggested as a possible reason for suboptimal management of osteoporosis. This might be one of the factors that explains the significant treatment gap for osteoporosis in Egypt (82.1%) [9]. Results of this work revealed that more than half of the participants (51%) rely on their personal experience and their clinical judgments, while they do not implement any specific guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in their standard practice. A major percentage of the participants (63.3%) opted to follow the international rather than national guidelines for management of osteoporosis, yet only 38% rated their adherence to the guidelines as high. Several research studies were carried out to evaluate healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward osteoporosis [17,18,19,20,21,22]. In a follow-up survey among Czech general practitioners, as many as 60% of the respondents adhered to the guidelines, meaning that they had been using them repeatedly [21]. In another study carried out in the United Arab Emirates to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of UAE physicians, more than 75% of the physicians who shared in the survey analysis were unaware of the presence of regional guidelines on osteoporosis [23]. The major difference is that the healthcare professionals who contributed to this study are specialists rather than general practitioners. Karbach et al. studied compliance with the guidelines for cardiovascular diseases [24]. The authors reported that the physicians’ knowledge of the guideline did not itself lead to better guideline implementation. These outcomes highlight the urgent need to translate evidence into practice and pay attention to improving physicians’ knowledge regarding the contemporary management of osteoporosis and its risk factors, particularly in rural areas.

Results of this work revealed significant differences in knowledge about osteoporosis management between orthopedic surgeons and physicians who contributed to this work. The mean knowledge score of the orthopedic surgeons was significantly lower than that of the rheumatologists. The time of initiation of osteoporotic medications after fragility fractures is of utmost importance to prevent subsequent fractures. The hesitancy over initiating osteoporotic medication immediately after fragility fractures was evident among the orthopedic surgeons, which may be due to concerns over their effect on fracture healing. Meanwhile, orthopedic surgeons had the attitude of prescribing osteoporosis medication rather than referring cases with fragility fractures to the nearby FLS center. Even after fragility fractures, the orthopedic surgeons were not concerned with osteoporosis management. These results contrast with the findings of the Japanese study carried out to assess the Japanese orthopedists’ interests in the prevention of fractures in the elderly from falls [25].

This study revealed that the frequency of responses regarding interests and strategies in the prevention of elderly fractures ranged between 51 and 57%. The findings of this study regarding the interest of orthopedic surgeons in osteoporosis and fracture prevention are of extreme value, as in some national health centers, orthopedic surgeons run high-cost osteoporosis medication services.

Overall, the outcomes of this work suggest that the healthcare professionals’ knowledge and compliance level with osteoporosis, as well as their self-reported quality of care, are lacking, particularly in rural areas and among orthopedic surgeons. A good percentage (58%) had a satisfactory knowledge level in domains on the risk of osteoporotic fractures and investigations of osteoporosis; however, 47.5% did not score satisfactorily in questions on pharmacotherapy, especially on pharmacotherapy for an osteoporotic person with a fragility fracture. These results are in agreement with earlier published data documenting a knowledge gap in pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis among primary care doctors [20, 22, and 23]. This knowledge gap would explain why only 36% of our participants were aware of FLS services in their areas, while 24% heard about them, but were unaware of their actual role in osteoporosis management.

This work adopted the quantitative research design. While qualitative research is advised when the subject is too complex to be answered by a simple “yes or no” [26], it cannot be statistically analyzed, as it follows a subjective approach and revolves around open-ended feedback. In contrast, quantitative research uses statistical and logical observations which facilitated getting a conclusion and comparing our results to previously published studies which adopted the same quantitative design [27]. Furthermore, quantitative research not only offers immediate evaluation of the individual’s knowledge or level of proficiency but also it generates factual, reliable outcome data that are usually generalizable to larger population [28].

In conclusion, this work has identified some of the barriers to implementing guidelines for osteoporosis and fragility fracture management. In the meantime, it highlights the urgency of intensifying efforts to develop the knowledge and attitude of the healthcare professionals dealing with this condition in Egypt. Post-fracture care and osteoporosis pharmacotherapy represent major gaps that require tackling as soon as possible. In particular, the policymakers in charge of the national insurance biologic and high-cost medication services should consider approaches to closing the big osteoporosis gap in Egypt and update their services and protocols for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis.

Data availability

The data sets used are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AACE :

-

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

- ACP :

-

American College of Physician (ACP)

- BMD :

-

Bone mineral density

- DXA :

-

Dual X-ray absorptiometry

- ESCEO :

-

European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis

- FLS :

-

Fracture liaison service

- FRAX :

-

Fracture risk assessment tool

- HCPs :

-

Healthcare professionals

- PRISMA :

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- Q :

-

Question

References

Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, Schunemann H, Eccles MP (2012) Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci 7:62

Willson ML, Vernooij RWM, Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group (2017) Gagliardi AR Questionnaires used to assess barriers of clinical guideline use among physicians are not comprehensive, reliable, or valid: a scoping review. J Clin Epidemiol 86:25–38

Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Ramsay C, Fraser C et al (2006) Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med 21:S14–S20

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A et al (2003) The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 348:2635–2645

Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D, Lankshear A, Lowson K, Watt I et al (2004) What’s the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients’ notes, and interviews. BMJ 329:999

Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, Hibbert PD, Westbrook JI, Coiera EW et al (2012) CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 197:100–105

Harvey NC et al (2017) Mind the (treatment) gap: a global perspective on current and future strategies for prevention of fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int 28(5):1507–1529

Cheung EYN et al (2016) Osteoporosis in East Asia: current issues in assessment and management. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2(3):118–133

El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Gadallah N, Mahran S, Fathi N, Abu Zaid MH, Tabra SAH, Hassan W, Elwakil W (2023) Osteoporosis treatment gap in patients at risk of fracture in Egypt: a multi-center, cross-sectional observational study. Arch Osteoporos 18(1):58

Gadallah N, El Miedany Y (2022) Operative secondary prevention of fragility fractures: national clinical standards for fracture liaison service in Egypt—an initiative by the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 49:11

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N (2010) Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD005470. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub2

Krause J, Van Lieshout J, Klomp R, Huntink E, Aakhus E, Flottorp S et al (2014) Identifying determinants for tailoring implementation in chronic diseases: an evaluation of different methods. Implement Sci 9:102

Kajermo KN, Bostrom AM, Thompson DS, Hutchinson AM, Estabrooks CA, Wallin L (2010) The BARRIERS scale—the barriers to research utilization scale: a systematic review. Implement Sci 5:32

El Miedany Y, Abu-Zaid MH, El Gaafary M et al (2021) Egyptian consensus on treat-to-target approach for osteoporosis: a clinical practice guideline from the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health and metabolic bone diseases. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 48:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-020-00056-9

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, The PRISMA Group (2009) Altman DG Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Gadallah N, Mahran S, Fathi N, Abu-Zaid MH, Tabra SAA, Shalaby RH, Abdelrafea B, Hassan W, Farouk O, Nafady M, Farghaly AM, Ibrahim SIM, Ali MA, Elmaradny KM, Eskandar SES, Elwakil W (2023) Incidence and geographic characteristics of the population with osteoporotic hip fracture in Egypt- by the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health. Arch Osteoporos 18(1):115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-023-01325-8

Taylor JC, Sterkel B, Utley M, Shipley M, Newman S, Horton M, Fitz-Clarence H (2001) Opinions and experiences in general practice on osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis and management. Osteoporosis Int 12:844–848

Pérez-Edo L, Ciria Recasens M, Castelo-Branco C, Orozco López P, Gimeno Marqués A, Pérez C et al (2004) Management of osteoporosis in general practice: a cross-sectional survey of primary care practitioners in Spain. Osteoporos Int 15:252–257

Economides PA, Kaklamani VG, Karavas I, Papaioannou GI, Supran S, Mirel RD (2000) Assessment of physician responses to abnormal results of bone densitometry studies. Endocr Pract 6:351–356

Skedros JG, Holyoak JD, Pitts TC (2006) Knowledge and opinions of orthopedic surgeons concerning medical evaluation and treatment of patients with osteoporotic fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:18–24

Harada A, Matsui Y, Mizuno M, Tokuda H, Niino N, Ohta T (2004) Japanese orthopedists’ interests in prevention of fractures in the elderly from falls. Osteoporos Int 15:560

Vytrisalova M, Touskova T, Fuksa L, Karascak R, Palicka V, Byma S, Stepan J (2017) How General Practitioners and Their Patients Adhere to Osteoporosis Management: A Follow-Up Survey among Czech General Practitioners. Front Pharmacol 8:258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00258

Beshyah S, Al Mehri W, Khalil A (2013) Osteoporosis and its management: knowledge, attitudes and practices of physicians in United Arab Emirates. Ibnosina J Med Biomed Sci 5(5):270–279

Karbach U, Schubert I, Hagemeister J, Ernstmann N, Pfaff H, Höpp H-W (2011) Physicians’ knowledge of and compliance with guidelines: an exploratory study in cardiovascular diseases. Dtsch Arztebl Int 108:61–66

Harada A, Matsui Y, Mizuno M, Tokuda H, Niino N, Ohta T (2004) Japanese orthopedists’ interests in prevention of fractures in the elderly from falls. Osteoporos Int 15(7):560–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-003-1582-1

Otani T (2017) What Is Qualitative Research? Yakugaku Zasshi 137(6):653–658. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi.16-00224-1

Goodman MS, Si X, Stafford JD, Obasohan A, Mchunguzi C (2012) Quantitative assessment of participant knowledge and evaluation of participant satisfaction in the CARES training program. Prog Community Health Partnersh 6(3):361–8. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2012.0051

Verhoef MJ, Casebeer AL (1997) Broadening horizons: integrating quantitative and qualitative research. Can J Infect Dis 8(2):65–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/1997/349145

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elwakil, W., El Gaafary, M. & El Miedany, Y. Screening and management of osteoporosis: a survey of knowledge, attitude, and practice among healthcare professionals in Egypt—a study by the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health. Osteoporos Int 35, 93–103 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06914-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06914-4