Abstract

Summary

Medication persistence and adherence are critical for osteoporosis outcomes. Using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, we found that persistence and adherence to teriparatide were low in Taiwanese patients with osteoporosis and that greater persistence and adherence were associated with a lower incidence of hip and other nonvertebral fractures.

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to determine the persistence and adherence to teriparatide treatment in Taiwanese patients with osteoporosis, and to examine the association between persistence and adherence to teriparatide with fracture risks.

Methods

Medical and pharmacy claims for 4,692 patients with vertebral or hip fractures and teriparatide prescriptions between 2005 and 2008 were identified (Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database). Persistence was the time from the start of treatment to the first 90-day gap between two teriparatide prescriptions. Adherence was the number of teriparatide pens (each pen is used over 1 month) prescribed over 24 months. Association of persistence and adherence to teriparatide with fracture incidence was assessed using adjusted Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

The proportion of patients persisting with teriparatide for >6 months and >12 months was 44.6 and 24.9 %, respectively. Over 24 months, 53.6 % of patients were adherent for >6 months and 33.9 % were adherent for >12 months. Patients persisting for >12 months had a significantly lower incidence of hip (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.61 [95 % confidence interval (CI), 0.40–0.93], P = 0.0229) and nonvertebral fracture (HR, 0.79 [95 % CI, 0.63–0.99], P = 0.0462) compared with those who persisted for ≤12 months. Patients adherent for >12 months had a lower incidence of hip (HR, 0.66 [95 % CI, 0.46–0.96], P = 0.0286) and nonvertebral fracture (HR, 0.81 [95 % CI, 0.66–0.99], P = 0.0377) compared with those adherent for ≤12 months.

Conclusions

Persistence and adherence to teriparatide over 24 months were low in Taiwanese patients with osteoporosis; greater adherence and persistence were associated with a lower incidence of nonvertebral fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a major, global health problem, especially in the aging population [1]. Fragility fractures, most commonly of the hip, vertebrae, and wrist, are a major complication of osteoporosis and are associated with increased mortality and reduced mobility [2]. Worldwide, approximately 9 million men and women older than 50 years experienced osteoporotic fractures in 2000 [3]. Of these, 1.6 million (18.2 %) were hip fractures and 1.4 million (15.8 %) were vertebral fractures [3]. Hip fracture alone is responsible for 41 % of the global osteoporosis morbidity burden [3]. Although hip fracture rates in Taiwan are decreasing or have plateaued [4, 5], they are among the highest in the world (299 per 100,000 population in 2010) [6]. The high hip fracture rates in Taiwan are proposed to be due to inadequate nutrition of the older generation in years past, poor geriatric care, a high risk of falls, and an aging population [7].

A number of effective treatments that aim to decrease the risk of fracture are available for patients with osteoporosis [2, 8]. These include antiresorptive drugs such as bisphosphonates; the selective estrogen receptor modulator, raloxifene; calcitonin; hormone replacement therapy; denosumab; and anabolic drugs, such as teriparatide [Forteo®; recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–34)] [9]. Antiresorptive drugs decrease the risk of osteoporotic fracture by slowing bone resorption and turnover, and maintaining or increasing bone mass [10]. In contrast, anabolic drugs decrease the risk of osteoporotic fracture [11] by stimulating bone formation [12].

Treatment persistence and adherence are important for the success of long-term therapies and can improve clinical outcomes [13]. However, adherence to osteoporosis medications is generally poor in real-world settings [14]. A medication possession ratio (MPR) ≥50 % is considered to be the minimal level of adherence required for a beneficial effect on fracture rate [15], and an inverse relationship between treatment adherence and fracture risk is well established [14, 15]. Previous studies conducted primarily in Caucasian populations have shown that only 30 to 50 % of patients adhere (MPR >80 %) to approved osteoporosis medications (bisphosphonates) after 2 years [16, 17]. Further, a number of studies have demonstrated that greater persistence or adherence to osteoporosis medications is associated with reduced fracture incidence [15–21].

Several studies on teriparatide have demonstrated reduced fracture incidence with greater persistence [18–21]. However, only one study, conducted in a real-world setting using a United States (US) claims database, has demonstrated that both greater persistence and adherence to teriparatide are associated with lower risks of all clinical vertebral and nonvertebral fractures [18]. In Taiwan, the Ministry of Health and Welfare approved the use of teriparatide for up to 24 months for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men at high risk for fragility fracture. However, the National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme in Taiwan only reimburses teriparatide use for up to 18 months. Persistence and adherence to teriparatide have not been examined in Taiwanese patients with osteoporosis and limited information is available in other Asian populations [22].

In this retrospective study, we examine the links between persistence and adherence to teriparatide treatment and the risk of fractures in patients with osteoporosis using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). First, we aimed to examine the clinical characteristics of Taiwanese patients with previous fracture who were treated with teriparatide. Second, we aimed to examine the association between persistence and adherence to teriparatide with the incidence of hip and other nonvertebral fractures in Taiwan.

Methods

Data source

The NHI program, established in 1995, is a public health insurance system in which participation is mandatory for all citizens of Taiwan. In 2014, 99.1 % of the population of Taiwan were enrolled [23]. The NHIRD has proven to be a valuable source of real-world clinical data for population-based studies, including studies on fractures and osteoporosis [24]. The current study is a retrospective, cohort study conducted in Taiwanese patients treated with teriparatide. Data of medical and pharmacy claims between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2010 in the NHIRD were supplied by the National Health Insurance Administration (formerly the Bureau of National Health Insurance), Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Study population

As per the NHI criteria for teriparatide reimbursement, patients were included if they had an International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for osteoporosis (733.xx) and/or major prevalent osteoporotic fractures (spine: ICD-9-CM codes 805.2, 805.4, 805.8, 806.2x, 806.4, 806.8; hip fracture: ICD-9-CM code 820.x) and had used teriparatide between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2008. Patients were excluded if they were aged <50 years, had Paget’s disease (ICD-9-CM code 731.0), had used teriparatide in the 12 months before the index date (date of first prescription for teriparatide), had open fractures (with the exception of hip) or fractures due to external causes, including high-trauma accidents (ICD-9-CM E codes), or had used teriparatide for greater than 24 months. Open fractures of the hip were not excluded as these fracture types may occur due to low impact trauma in frail older adults in the real-world setting.

Treatment

Patients were prescribed teriparatide 20 μg daily (Forteo®, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) by subcutaneous injection for a maximum of 24 months. Patients were followed for 24 months after index teriparatide prescription.

Persistence and adherence

Persistence was determined as the time from the start of treatment to the first 90-day gap between two teriparatide prescriptions. Patients were classified as persisting with teriparatide for ≤12 months or >12 months. Adherence was defined by the number of teriparatide pens (each pen is intended for 1 month of use) prescribed within the 24-month study period. Hence, patients with a prescription for teriparatide were assumed to be adherent if they were using one pen per month for the total number of months where a prescription was recorded. The rate of adherence was calculated by dividing the total number of pens prescribed over a given period by the maximum number of pens that could be used over that period. Although the NHI reimbursement for teriparatide is for a maximum of 18 pens in 24 months, prescription of teriparatide is not required to go through pre-authorization in Taiwan. Therefore, some patients could have been prescribed more than the reimbursed maximum number of pens within the 24-month study period. The concept of MPR is not used in the currently study because of this special prescription restriction in Taiwan. Patients were classified as being adherent for ≤12 months or >12 months of teriparatide use.

Fractures

New nonvertebral fractures (ICD-9-CM codes hip: 820.x; shoulder: 812.0x, 812.2x; forearm: 13.4x, 813.8x; clavicle: 810.0x; pelvis: 808.0, 808.2, 808.4x, 808.8; rib: 807.0x; femur/upper leg: 821.00, 821.01, 821.21, 821.22, 821.23, 821.29, 822.9; lower leg: 823.0x, 823.2x, 823.4x, 823.8x) occurring during the study period were summarized. New fractures were defined as new fragility fractures that occurred ≥90 days after the index date in order to provide sufficient time for therapeutic effects to begin after exposure to teriparatide. Data for hip fracture were obtained from inpatient claims; data for other fracture types were obtained from inpatient and outpatient claims.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized for the total population and reported by persistence and adherence groups. Assessment of imbalance was performed using a two-sample t test for continuous variables and a chi-squared test for categorical variables. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The association of persistence and adherence to teriparatide with fracture incidence was assessed using unadjusted Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional hazard models. Patient data were censored if patients reached the study endpoint (new nonvertebral fracture) or were no longer covered by the NHI (a proxy measure of death). Cox models were adjusted at baseline for demographics (age, sex, and previous fractures), and 12 months prior to index teriparatide prescription for concomitant osteoporosis medications, other concomitant medications affecting bone, and comorbidities. Models were also stratified by adherence and persistence, and in some instances adherence was treated as a time-varying covariate. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

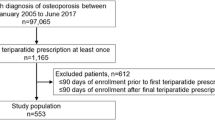

Of the 6,997,079 patients who lodged medical and pharmacy claims in the NHIRD between 2005 and 2008, 4,624 were included in the study (Fig. 1). Most (85.0 %) patients were female and almost two thirds (65.5 %) of the patients were aged ≥75 years (Table 1).

Prevalent vertebral and hip fractures were reported in 87.7 and 20.3 % of patients, respectively (Table 1).

Comorbidities and other medications

The majority (85.4 %) of patients had a diagnosis of osteoporosis within 12 months of the index date (Table 1). The most frequently reported (affecting >20 % of patients) comorbidities were asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (27.6 %), cataracts (25.0 %), and diabetes mellitus (24.2 %) (Table 1). Previous treatments for osteoporosis in the 12-month pre-index period were alendronate (31.7 % of patients), calcitonin (26.7 % of patients), raloxifene (20.2 % of patients), and ibandronate (0.2 % of patients) (Table 1). Overall, close to 80 % of patients received previous treatment for osteoporosis prior to the initiation of teriparatide. Common (>20 % of patients) concomitant medications prescribed during the pre-index period that affected bone included glucocorticoids (29.7 %) and anticonvulsants (20.3 %).

After discontinuing teriparatide, 2,687 (58.1 %) patients switched to one or more other osteoporosis medications. Of these 2,004 (74.6 %) patients switched to one osteoporosis medication only, 1,725 (64.2 %) switched to alendronate, 1,149 (42.8 %) switched to raloxifene, and 572 (21.3 %) switched to calcitonin.

Persistence

Persistence with teriparatide during the 24-month period was low (Fig. 2). Less than half (44.6 %) of patients persisted with teriparatide for >6 months, and only 1 in 4 (24.9 %) patients persisted with teriparatide for >12 months. Persistence with teriparatide for >12 months was greater in patients younger than 75 years than in older patients (Table 1). The proportion of patients persisting for >12 months was significantly (P < 0.05) greater than the proportion persisting for ≤12 months in patients who received previous osteoporosis medications (except for ibandronate), had previous vertebral fractures, had cataracts, depression, or received immunosuppressants (Table 1). In contrast, the proportion persisting >12 months was lower than the proportion persisting for ≤12 months in patients who had previous hip, leg, or shoulder fractures, had renal diseases, or received glucocorticoids (Table 1).

Adherence

Over the 24-month study period, 53.6 % of patients were adherent for >6 months and 33.9 % were adherent for >12 months. Adherence to teriparatide was greater in patients younger than 75 years than among older patients (particularly those ≥85 years) (Table 1). The proportion of patients who were adherent for >12 months was significantly (P < 0.05) greater than the proportion who were adherent for ≤12 months in patients who received previous alendronate or calcitonin, had previous vertebral fracture, had a diagnosis of osteoporosis during the 12-month pre-index period, cataracts, or depression, or received immunosuppressants or hormone replacement therapy. In contrast, the proportion of patients who were adherent for >12 months was lower than the proportion who were adherent for ≤12 months in patients who had previous hip or leg fractures, or had diabetes mellitus or renal diseases (Table 1).

Effect of persistence and adherence on fracture

Persistence and adherence to teriparatide had a significant effect on the risk of hip and other nonvertebral fractures (Table 2, Fig. 3). Persistence for >12 months was associated with a lower incidence of hip (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.61, 95 % confidence interval [CI]: 0.40–0.93, P = 0.0229) and nonvertebral fractures (HR 0.79, 95 % CI: 0.63–0.99, P = 0.0462) compared with patients persisting with teriparatide for ≤12 months (Table 2). Adherence to teriparatide >12 months was associated with lower incidence of hip (HR 0.66, 95 % CI: 0.46–0.96, P = 0.0286; inpatient claim data) and nonvertebral (HR 0.81, 95 % CI: 0.66–0.99, P = 0.0377; combined inpatient and outpatient claim data) fractures compared with adherence ≤12 months) (Table 2). No association between persistence or adherence and the incidence of nonvertebral fracture was found at any individual site other than the hip (Table 2).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the association of persistence and adherence to teriparatide with fracture risk in real-world clinical practice in Taiwan. We found that both persistence and adherence to teriparatide in Taiwanese patients with osteoporosis were low, and that lower persistence and adherence were associated with a significantly increased risk of hip and other nonvertebral fractures in patients who had previous fracture(s). Our results indicate that persistence and adherence to teriparatide are inversely associated with fracture risk in patients with osteoporosis. Thus, improving patient persistence and adherence has an important role in fracture prevention in patients treated with teriparatide.

We found that the incidence of hip and all nonvertebral fractures (when pooled for analysis) decreased significantly with increasing persistence and adherence to teriparatide. There were also reductions in the incidences of shoulder, forearm, clavicle, pelvis, leg, and rib fractures with greater persistence and adherence, although these were not statistically significant due to low patient numbers. These findings are in agreement with those from other real-world studies. In a similar, real-world study in the USA, which used data from a claims database, the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures decreased significantly with increasing persistence and adherence to teriparatide [18]. In the European Forsteo Observational Study, significantly greater reductions in vertebral and nonvertebral fracture rates were observed in patients treated with teriparatide for 12 to 18 months compared with those treated for 6 months or less [25]. However, it is also important to acknowledge that adherence is not merely a random behavior, and adherent patients may have superior outcomes for many reasons unrelated to medication usage. This is supported by the observation that adherent patients administered placebo fare better than nonadherent patients [26].

We found that the proportion of Taiwanese patients who persisted with teriparatide for more than 12 months was low (about 1 in 4). To our knowledge, this is the first study of persistence with teriparatide in an Asian country other than Japan. The persistence rate was lower than persistence rates reported at 12 months in similar real-world studies in Japan (61.0 %), the USA (56.7–69.0 %), and Europe (77.0 %) [18, 22, 25, 27]. One of the above studies [18] only included patients with two or more prescriptions for teriparatide. Despite the more conservative definition of persistence in the Yu et al. study (≤45 day gap between 2 prescriptions compared with 90 days), the persistence rate was still much higher than in the current study (69.0 versus 24.9 %) [18]. The higher persistence with teriparatide treatment in the above studies is probably because patients in Taiwan only receive reimbursement for up to 18 months of use, even though the approved treatment duration for teriparatide is up to 24 months. In addition, the high workload common in many outpatient clinics in Taiwan means that patients often do not receive the appropriate education or instructions required, which may have resulted in suboptimal patient education in our study. Successful implementation of a patient support program, consisting of regular telephone-based, nurse-directed contact, has been shown to enhance patient persistence through the provision of ongoing education and self-management advice [28, 29]. Another recent strategy to increase persistence and address care gaps in osteoporosis management has been the establishment of coordinated care models, such as fracture liaison services, which have resulted in higher rates of osteoporosis diagnoses [30], increased initiation of osteoporosis medications for fracture risk reduction [31], and improved persistence with medication regimens [31].

We found that the adherence rates in our study were also low, with only 33.9 % of patients being adherent for >12 months. This low rate of adherence is primarily because of the restricted reimbursement criterion of up to 18 months of use. However, adherence to antiosteoporotic drugs, in general, is low in Taiwan. Low rates of adherence have been reported for alendronate (38.2 % patients with MPR ≥80 % at 12 months) in Taiwan using the NHIRD [32], and to bisphosphonates and calcitonin (37.5 % patients with MPR ≥80 % at 24 months) [33]. In a retrospective analysis of NHIRD data from 32,604 patients initiating bisphosphonate therapy in Taiwan, nearly 50 % of patients were found to be nonadherent (MPR < 80 %) to bisphosphonates at 3 months, and approximately 70 % were nonadherent at 1 year [34]. A significant association between adherence and refracture risk was observed, with highly adherent (>80 %) patients displaying significantly lower levels of refracture compared to patients with low (<80 %) adherence [34]. In another study, data from patients with (n = 8,027) and without (n = 79,388) secondary fracture in Taiwan were retrospectively analyzed, with a significant inverse association found between bisphosphonate therapy and the risk of secondary fracture [35].

Suboptimal persistence and adherence to antiresorptive treatment is associated with increased risk of fragility fractures [15, 17]. Despite this, improving persistence/adherence to osteoporosis medications remains a challenge in many Asian countries. Persistence and adherence to osteoporosis medications varies throughout Asia, but is generally lower than in the US and Europe. In a South Korean study of bisphosphonates, only 6.7 % of patients with hip fractures had an MPR ≥80 % and only 12.3 % persisted for 12 months [36]. In a pooled, retrospective study of osteoporosis medication in Singapore, 83 % of patients had an MPR ≥80 % at 12 months [37], including five patients on teriparatide with an average MPR of 60 % [37]. In a study of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis throughout Asia that compared raloxifene and bisphosphonates, 50.2 and 37.5 % of patients completed the 12-month study, respectively [38]. The major reason given for discontinuation for both groups was “lost to follow-up” (33.1 and 37.5 % of patients in the raloxifene and bisphosphonate groups, respectively) [38]. Other reasons included “chose to leave”, “stopped treatment”, and “changed treatment” [38].

A number of factors may contribute to the lower persistence and adherence to osteoporosis medications in Taiwan and in Asia in general. These factors include out-of-pocket costs for patients due to high therapy costs, lack of health insurance, inadequate follow-up, side effects of treatment, lack of patient education, and asymptomatic disease [39, 40]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that multiple factors such as sex [41], health care provider (general practitioner versus specialist) [41], and severity of disease [25] may also affect persistence and adherence to teriparatide. The primary reasons for the low persistence and adherence to teriparatide in Taiwan may be because of the restricted reimbursement criteria of up to 18 months, inappropriate follow-up of patients after discharge from hospital, and the fact that the majority of prescribers of antiosteoporosis drugs in Taiwan are orthopedists, who are focussed primarily on fracture repair and restoration of mobility [39]. Findings from a retrospective study in Taiwan have shown that patients who receive antiosteoporosis drugs from orthopedists have lower persistence and adherence to treatment than patients who receive antiosteoporosis drugs from bone specialists [39]. Cost is unlikely to be a contributor to the low persistence and adherence to teriparatide because patients in the NHIRD were reimbursed by the NHI with limited copayments.

In our study, a substantial proportion of patients (41.9 %) were not prescribed osteoporosis medication subsequent to teriparatide discontinuation. This finding is of concern given that steady declines in BMD are expected following teriparatide discontinuation [42]. Clinical trial evidence examining the effect of sequential therapy on bone markers suggests that subsequent treatment with an antiresorptive, such as alendronate, may help preserve and even extend BMD gains achieved with teriparatide therapy [43]. Unlike antiresorptives, teriparatide has been shown to stimulate bone formation [44], restore trabecular microarchitecture [44], and increase cortical thickness [44]. In the longer term, these changes are expected to confer a reduced risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fracture, though this has not yet been conclusively proven.

This study was a retrospective analysis of data obtained from real-world clinical practice, which is strengthened by the large sample size and generalizability to the Taiwanese population. However, this study has several limitations common to studies of claims-based databases using administrative codification. These include an inherent bias due to its retrospective design and, because the study data were obtained from a claims database, there is no confirmation that teriparatide was actually administered as indicated. Thus, fracture incidence may be under- or overestimated and adherence may be overestimated. However, in addition to adjusting for the previously mentioned variables, sensitivity analyses were conducted treating adherence as a time-dependant covariate for inpatient and outpatient claims for all nonvertebral fractures including hip. The HR point estimates (0.87, 95 % CI: 0.77–0.99; P = 0.0288) from these analyses also indicated a lower fracture risk with increased teriparatide exposure. Further, while every attempt was made to exclude patients with open and trauma-related fractures from the analysis, some may have inadvertently been included due to the potential for improper coding of some fractures (such as ankle fractures) and lack of routine trauma coding in clinical practice. In addition, identification of osteoporosis occurred by ICD-9-CM coding for osteoporosis and/or major prevalent osteoporotic fractures (spine or hip fracture) as this was mandatory for teriparatide reimbursement by the NHI. However, using this approach, it is recognized that patients with previous fragility fractures from other sites would be excluded. Finally, an evaluation of the association between post-discontinuation treatment and fracture risk was not conducted due to the potential influence of missing data and unmeasured confounders inherent to claims databases such as the one used in our study. This bias would be further exaggerated given the high switch rate (58.1 %) from teriparatide to other osteoporosis medications.

In conclusion, this is the first study to examine the association of both persistence and adherence to teriparatide with fracture risk in real-world clinical practice in Taiwan. The data confirmed that greater persistence and adherence were associated with a significantly reduced incidence of nonvertebral fractures (including hip fractures). However, both persistence and adherence to teriparatide were low in Taiwanese patients with osteoporosis. Programs supporting patient adherence and persistence, such as patient support programs and fracture liaison services, represent promising strategies to help address shortfalls in osteoporosis management through the provision of patient education and self-management techniques.

References

Colon-Emeric CS, Saag KG (2006) Osteoporotic fractures in older adults. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 20:695–706

Inderjeeth CA, Chan K, Kwan K, Lai M (2012) Time to onset of efficacy in fracture reduction with current anti-osteoporosis treatments. J Bone Miner Metab 30:493–503

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733

Chan DC, Lee YS, Wu YJ, Tsou HH, Chen CT, Hwang JS, Tsai KS, Yang RS (2013) A 12-year ecological study of hip fracture rates among older Taiwanese adults. Calcif Tissue Int 93:397–404

Wang CB, Lin CF, Liang WM, Cheng CF, Chang YJ, Wu HC, Wu TN, Leu TH (2013) Excess mortality after hip fracture among the elderly in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Bone 56:147–153

Kanis JA, Oden A, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Wahl DA, Cooper C (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23:2239–2256

Chie WC, Yang RS, Liu JP, Tsai KS (2004) High incidence rate of hip fracture in Taiwan: estimated from a nationwide health insurance database. Osteoporos Int 15:998–1002

Papapoulos SE (2015) Anabolic bone therapies in 2014: new bone-forming treatments for osteoporosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11:69–70

Bernabei R, Martone AM, Ortolani E, Landi F, Marzetti E (2014) Screening, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis: a brief review. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 11:201–207

Russell RG, Watts NB, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ (2008) Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: similarities and differences and their potential influence on clinical efficacy. Osteoporos Int 19:733–759

Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR et al (2001) Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441

Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW et al (2005) Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis: a review of the evidence and suggested guidelines for its use. Endocr Rev 26:688–703

Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B (2005) Medication adherence and persistence: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther 22:313–356

Modi A, Siris ES, Tang J, Sen S (2015) Cost and consequences of noncompliance with osteoporosis treatment among women initiating therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 31:757–765

Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgstrom F, Herings RM, Silverman SL (2009) Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med 122:S3–S13

Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Yood RA, Kahler KH (2007) Consequences of poor compliance with bisphosphonates. Bone 41:882–887

Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M, Herings RM (2008) Loss of treatment benefit due to low compliance with bisphosphonate therapy. Osteoporos Int 19:511–517

Yu S, Burge RT, Foster SA, Gelwicks S, Meadows ES (2012) The impact of teriparatide adherence and persistence on fracture outcomes. Osteoporos Int 23:1103–1113

Lindsay R, Miller P, Pohl G, Glass EV, Chen P, Krege JH (2009) Relationship between duration of teriparatide therapy and clinical outcomes in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 20:943–948

Rajzbaum G, Grados F, Evans D, Liu-Leage S, Petto H, Augendre-Ferrante B (2014) Treatment persistence and changes in fracture risk, back pain, and quality of life amongst patients treated with teriparatide in routine clinical care in France: results from the European Forsteo Observational Study. Joint Bone Spine 81:69–75

Suk KS, Lee HM, Moon SH, Kim HJ, Kim HS, Park JO, Lee BH (2014) At least one cyclic teriparatide administration can be helpful to delay initial onset of a new osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. Yonsei Med J 55:1576–1583

Tanaka I, Sato M, Sugihara T, Faries DE, Nojiri S, Graham-Clarke P, Flynn JA, Burge RT (2013) Adherence and persistence with once-daily teriparatide in Japan: a retrospective, prescription database, cohort study. J Osteoporos 2013:Article ID 654218

National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan ROC (2014) National Health Insurance Annual Report 2014–2015. http://www.hpa.gov.tw/English/file/ContentFile/201502140514171717/2014_Health_Promotion_Administration_Annual_Report.pdf. Accessed 31 July 2015

Chien L-C, Cheng H-M, Chen W-C, Tsai M-C (2010) Pelvic fracture and risk factors for mortality: a population-based study in Taiwan. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 36:131–137

Langdahl BL, Rajzbaum G, Jakob F et al (2009) Reduction in fracture rate and back pain and increased quality of life in postmenopausal women treated with teriparatide: 18-month data from the European Forsteo Observational Study (EFOS). Calcif Tissue Int 85:484–493

Curtis JR, Larson JC, Delzell E et al (2011) Placebo adherence, clinical outcomes, and mortality in the women’s health initiative randomized hormone therapy trials. Med Care 49:427–435

Foster SA, Foley KA, Meadows ES, Johnston JA, Wang SS, Pohl GM, Long SR (2011) Adherence and persistence with teriparatide among patients with commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid insurance. Osteoporos Int 22:551–557

Nogues X, Luz Rentero M, Rodriguez AL (2014) Use of an educational support program to assist patients receiving injectable osteoporosis treatment: experience with teriparatide. Curr Med Res Opin 30:287–296

Briot K, Ravaud P, Dargent-Molina P, Zylberman M, Liu-Leage S, Roux C (2009) Persistence with teriparatide in postmenopausal osteoporosis; impact of a patient education and follow-up program: the French experience. Osteoporos Int 20:625–630

McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C (2003) The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 14:1028–1034

Boudou L, Gerbay B, Chopin F, Ollagnier E, Collet P, Thomas T (2011) Management of osteoporosis in fracture liaison service associated with long-term adherence to treatment. Osteoporos Int 22:2099–2106

Lin TC, Yang CY, Yang YH, Lin SJ (2011) Alendronate adherence and its impact on hip-fracture risk in patients with established osteoporosis in Taiwan. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90:109–116

Chiu CK, Kuo MC, Yu SF, Su BY, Cheng TT (2013) Adherence to osteoporosis regimens among men and analysis of risk factors of poor compliance: a 2-year analytical review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:276

Soong YK, Tsai KS, Huang HY, Yang RS, Chen JF, Wu PCH, Huang KE (2013) Risk of refracture associated with compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in Taiwan. Osteoporos Int 24:511–521

Shen S-H, Huang K-C, Tsai Y-H, Yang T-Y, Lee M-S, Ueng S-W, Hsu R-W (2014) Risk analysis for second hip fracture in patients after hip fracture surgery: a nationwide population-based study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15:725–731

Lee YK, Ha YC, Choi HJ, Jang S, Park C, Lim YT, Shin CS (2013) Bisphosphonate use and subsequent hip fracture in South Korea. Osteoporos Int 24:2887–2892

Chandran M, Tan MZ, Cheen M, Tan SB, Leong M, Lau TC (2013) Secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures--an “OPTIMAL” model of care from Singapore. Osteoporos Int 24:2809–2817

Pasion EG, Sivananthan SK, Kung AW et al (2007) Comparison of raloxifene and bisphosphonates based on adherence and treatment satisfaction in postmenopausal Asian women. J Bone Miner Metab 25:105–113

Yu SF, Yang TS, Chiu WC, Hsu CY, Chou CL, Su YJ, Lai HM, Chen YC, Chen CJ, Cheng TT (2013) Non-adherence to anti-osteoporotic medications in Taiwan: physician specialty makes a difference. J Bone Miner Metab 31:351–359

Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353:487–497

Kyvernitakis I, Kostev K, Kurth A, Albert US, Hadji P (2014) Differences in persistency with teriparatide in patients with osteoporosis according to gender and health care provider. Osteoporos Int 25:2721–2728

Prince R, Sipos A, Hossain A et al (2005) Sustained nonvertebral fragility fracture risk reduction after discontinuation of teriparatide treatment. J Bone Miner Res 20:1507–1513

Black DM, Bilezikian JP, Ensrud KE et al (2005) One year of alendronate after one year of parathyroid hormone (1–84) for osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 353:555–565

Chen P, Miller PD, Recker R, Resch H, Rana A, Pavo I, Sipos AA (2007) Increases in BMD correlate with improvements in bone microarchitecture with teriparatide treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 22:1173–1180

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Debra Wang, Cian-Hui Hong, and Shu-Chiung Hwang for contributing to the management of this study. This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, manufacturer/licensee of teriparatide (Forteo®). Medical writing assistance was provided by Serina Stretton, PhD, CMPP and Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP of ProScribe—Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Role of the sponsor

Eli Lilly and Company was involved in the study design, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

CHCC, AJMB, RB, LJ, and SG are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. CHCC, RB, LJ, and SG own stock in Eli Lilly and Company. All other authors received a research grant from Eli Lilly to conduct this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, DC., Chang, C.HC., Lim, LC. et al. Association between teriparatide treatment persistence and adherence, and fracture incidence in Taiwan: analysis using the National Health Insurance Research Database. Osteoporos Int 27, 2855–2865 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3611-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3611-x