Abstract

Summary

In this large retrospective study of men with presumed osteoporosis, we estimate the rate of osteoporosis-related fractures in men age ≥30 years. Our results suggest that spine and hip fractures continue to be a considerable disease burden for osteoporotic men of all ages.

Introduction

The purposes of this study were to describe a cohort of men with presumed osteoporosis and estimate the incidence rates of fractures by age.

Methods

Using US administrative claims data, we identified 43,813 men ≥30 years old with an osteoporosis diagnosis or use of an osteoporosis medication. Men were followed for a minimum of 12 months after diagnosis or treatment of osteoporosis (index date), until the earliest of fracture (hip, spine, pelvis, distal femur, humerus, wrist, forearm), disenrollment, or study end date.

Results

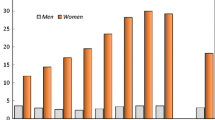

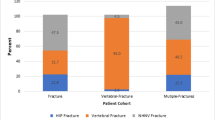

During the study period, there were 3834 first fractures following the index date and 3303 fractures in the 6-month period prior to the diagnosis/treatment of osteoporosis. Incidence rates of osteoporosis-related fracture, estimated from the index date onward, increased with age, although did not significantly differ from one another in younger age groups (30–49 and 50–64 years). Spine fractures had the highest incidence rate in men across all age groups, increasing from 10.8 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) (95 % confidence interval (CI) 9.1, 12.7), 12.2 per 100,000 p-yrs (95 % CI 11.2, 13.3), and 15.3 per 100,000 p-yrs (95 % CI 13.8, 16.9) in men 30–49, 50–64, and 65–74 years to 33.4 per 100,000 p-yrs (95 % CI 31.5, 35.4) in men ≥75 years. Hip fractures were the second most common, with the incidence rate reaching 16.2 per 100,000 (95 % CI 14.9, 17.6) in the ≥75-year group.

Conclusion

These incidence rates suggest that spine and hip fractures are a considerable disease burden for men of all ages diagnosed and/or treated for osteoporosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Consensus Development Statement (1997) Who are candidates for prevention and treatment for osteoporosis? Osteoporos Int 7(1):1–6

Curtis JR, Adachi JD, Saag KG (2009) Bridging the osteoporosis quality chasm. J Bone Miner Res 24(1):3–7

Gruntmanis U (2007) Male osteoporosis: deadly, but ignored. Am J Med Sci 333(2):85–92, Review

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12):1726–1733

Johnell O, Kanis J (2005) Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 16(2):S3–S7, Review

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA 301(5):513–521

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152(6):380–390

Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB (2009) Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA 302(14):1573–1579

Aharonoff GB, Koval KJ, Skovron ML, Zuckerman JD (1997) Hip fractures in the elderly: predictors of one year mortality. J Orthop Trauma 11(3):162–165

Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Vallero F, Di Monaco R, Tappero R (2012) Men recover ability to function less than women do: an observational study of 1094 subjects after hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 91(4):309–315

Seeman E, Bianchi G, Khosla S, Kanis JA, Orwoll E (2006) Bone fragility in men—where are we? Osteoporos Int 17(11):1577–1583

Larijani B, Hossein-Nezhad A, Mojtahedi A, Pajouhi M, Bastanhagh MH, Soltani A, Mirfezi SZ, Dashti R (2005) Normative data of bone mineral density in healthy population of Tehran, Iran: a cross sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2:6–38

Lynn HS, Lau EM, Au B, Leung PC (2005) Bone mineral density reference norms for Hong Kong Chinese. Osteoporos Int 16(12):1663–1668

Pérez-Castrillón JL, Martín-Escudero JC, del Pino-Montes J, Blanco FS, Martín FJ, Paredes MG, Fernández FP, Arés TA (2005) Prevalence of osteoporosis using DXA bone mineral density measurements at the calcaneus: cut-off points of diagnosis and exclusion of osteoporosis. J Clin Densitom 8(4):404–408

Richy F, Gourlay ML, Garrett J, Hanson L, Reginster JY (2004) Osteoporosis prevalence in men varies by the normative reference. J Clin Densitom 7(2):127–133

Melton LJ 3rd, Atkinson EJ, O'Connor MK, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL (1998) Bone density and fracture risk in men. J Bone Miner Res 13(12):1915–1923

Schneeweiss S, Avorn J (2005) A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol 58:323–337

MarketScan® Research Databases User Guide and Database Dictionary Commercial Claims and Encounters (2007) Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits. Data Year Edition

Adamson DM, Chang S, Hansen LG (2008) Health research data for the real world: the Marketscan databases. Thompson Healthcare, New York

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45:613–619

Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, de Laet CE, Burger H, Seeman E, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, van Leeuwen JP, Pols HA (2004) Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone 34(1):195–202

Melton LJ 3rd, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM (1999) Fracture incidence in Olmsted County, Minnesota: comparison of urban with rural rates and changes in urban rates over time. Osteoporos Int 9(1):29–37

Freitas SS, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud KE, Fink HA, Bauer DC, Cawthon PM, Lambert LC, Orwoll ES, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Research Group (2008) Rate and circumstances of clinical vertebral fractures in older men. Osteoporos Int 19(5):615–623

Sanders KM, Seeman E, Ugoni AM, Pasco JA, Martin TJ, Skoric B, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA (1999) Age- and gender-specific rate of fractures in Australia: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 10(3):240–247

Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J (1998) Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: the influence of age and gender. J Bone Jt Surg Br 80(2):243–248

Cooper C, O'Neill T, Silman A (1993) The epidemiology of vertebral fractures. European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study Group. Bone 14(1):S89–S97, Review

Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM, Bauer DC, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Lewis CE, Barrett-Connor E, Cummings SR, Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) and Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) Research Groups (2007) High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA 298(20):2381–2388

Melton LJ 3rd (2008) Does high-trauma fracture increase the risk of subsequent osteoporotic fracture? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4(6):316–317

Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA, Beaton DE (2004) Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 15(10):767–778

Kiebzak GM, Beinart GA, Perser K, Ambrose CG, Siff SJ, Heggeness MH (2002) Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med 162(19):2217–2222

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.Recommended Actions to Improve External-Cause-of-Injury Coding in State-Based Hospital Discharge and Emergency Department Data Systems. Atlanta, GA (2009). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; December

Strategies to Improve External Cause-of-Injury Coding in State-Based Hospital Discharge and Emergency Department Data Systems (2008) Recommendations of the CDC Workgroup for Improvement of External Cause-of-Injury Coding. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 28, March

Cuddihy MT, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd (1999) Forearm fractures as predictors of subsequent osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 9(6):469–475

Lindau TR, Aspenberg P, Arner M, Redlundh-Johnell I, Hagberg L (1999) Fractures of the distal forearm in young adults An epidemiologic description of 341 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 70(2):124–128

Melton LJ 3rd, Amadio PC, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM (1998) Long-term trends in the incidence of distal forearm fractures. Osteoporos Int 8(4):341–348

Melton LJ 3rd, Sampson JM, Morrey BF, Ilstrup DM (1981) Epidemiologic Features of Pelvic Fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Res. Mar-Apr (155): 43–47.

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P, Eisman J, Fujiwara S, Garnero P, Kroger H, McCloskey EV, Mellstrom D, Melton LJ, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35(2):375–382

Langsetmo L, Goltzman D, Kovacs CS, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Kreiger N, Josse R, Papaioannou A, Olszynski WP, Jamal SA, CaMos Research Group (2009) Repeat low-trauma fractures occur frequently among men and women who have osteopenic BMD. J Bone Miner Res 24(9):1515–1522

Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA (2007) Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA 297:387–394

Briot K, Cortet B, Trémollières F, Sutter B, Thomas T, Roux C, Audran M, ComitéScientifique du GRIO (2009) Male osteoporosis: diagnosis and fracture risk evaluation. Joint Bone Spine 76(2):129–133

Audran M, Cortet B (2009) Prevalence of Osteoporosis in Male Patients with Risk Factors. J Bone Miner Res 24 (Suppl 1)

Frost M, Wraae K, Gudex C, Nielsen T, Brixen K, Hagen C, Andersen M (2012) Chronic diseases in elderly men: underreporting and underdiagnosis. Age Ageing 41(2):177–183

Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (2001) Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86(2):724–731

Lix LM, Yogendran MS, Leslie WD, Shaw SY, Baumgartner R, Bowman C, Metge C, Gumel A, Hux J, James RC (2008) Using multiple data features improved the validity of osteoporosis case ascertainment from administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 61(12):1250–1260

Abelson A, Ringe JD, Gold DT, Lange JL, Thomas T (2010) Longitudinal change in clinical fracture incidence after initiation of bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 21(6):1021–1029

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Michael Lane for his assistance in analyzing the data.

Conflicts of interest

This study was funded by Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA; UG and PDM did not receive any remuneration for this study. ADM, CDO, and RBW are employees of and have stock ownership in Amgen, Inc. JWH is an employee of Ardea Biosciences and has stock ownership in Ardea and Amgen Inc. UG has received research grants from Amgen Inc, GSK, Novartis, and Proctor and Gamble. PDM has received research grants and consulting fees/other renumeration from Amgen Inc, GE Lunar, Lilly, Proctor and Gamble, Merck, Radius, Takeda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manthripragada, A.D., O’Malley, C.D., Gruntmanis, U. et al. Fracture incidence in a large cohort of men age 30 years and older with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 26, 1619–1627 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3035-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3035-z