Abstract

Summary

Persistence with postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) medications is not well characterized beyond 12 months. Of 3,011 postmenopausal women treated in primary care, 36.8 % continued baseline PMO medication during 36 months of follow-up. Many factors were associated with nonpersistence, including newly initiating or switching therapy, and reporting moderate to severe side effects.

Introduction

Persistence with postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) medications is not well characterized beyond 12 months. We describe 24- and 36-month persistence using patient-reported data from women with different PMO treatment histories in the US primary care setting.

Methods

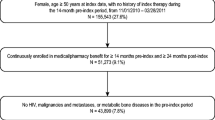

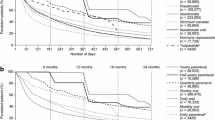

Data from 3,011 participants of the Prospective Observational Scientific Study Investigating Bone Loss Experience (POSSIBLE US™, 10/2005–12/2008) and Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the probability of persisting (i.e., not discontinuing or switching PMO agents) with baseline PMO medication and hazard ratios for predictors of nonpersistence 24 and 36 months after study entry.

Results

The probability of persisting with the baseline medication was 46.2 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 44.2–48.1 %) during 24 months of follow-up and 36.8 % (95 % CI 34.7–38.9 %) during 36 months of follow-up. In adjusted analyses, newly initiating therapy or switching to a new agent, reporting moderate to severe side effects, having lower disease-specific quality of life scores, smoking, and residing in the South or West USA (all measured at study entry) were independent predictors of nonpersistence in both time periods. The majority of participants who discontinued therapy and had the opportunity to reinitiate (i.e., discontinued ≥4 months before the end of follow-up) restarted therapy (24 months 69 %; 36 months 75 %).

Conclusions

In this primary care cohort, a minority of women continued their baseline PMO therapy during a 24- to 36-month follow-up. Supporting patients during the initiation of a new therapy or if side effects occur may improve persistence and increase the therapeutic benefit of PMO medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2010) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM et al (2007) High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA 298:2381–2388

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy (2001) Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285:785–795

Levis S, Theodore G (2012) Summary of AHRQ’s comparative effectiveness review of treatment to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis: update of the 2007 report. J Manag Care Pharm 18:S1–S15, discussion S13

Adachi J, Lynch N, Middelhoven H, Hunjan M, Cowell W (2007) The association between compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy and fracture risk: a review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 8:97

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 18:1023–1031

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, Vanoverloop J, Sumkay F, Vannecke C, Deswaef A, Verpooten GA, Reginster JY (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 19:811–818

Wade SW, Curtis JR, Yu J, White J, Stolshek BS, Merinar C, Balasubramanian A, Kallich JD, Adams JL, Viswanathan HN (2012) Medication adherence and fracture risk among patients on bisphosphonate therapy in a large United States health plan. Bone 50:870–875

Downey TW, Foltz SH, Boccuzzi SJ, Omar MA, Kahler KH (2006) Adherence and persistence associated with the pharmacologic treatment of osteoporosis in a managed care setting. South Med J 99:570–575

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 21:1943–1951

Kayser J, Ettinger B, Pressman A (2001) Postmenopausal hormonal support: discontinuation of raloxifene versus estrogen. Menopause 8:328–332

Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di Munno O, Giannini S, Minisola S, Sinigaglia L, Adami S, Treatment of Osteoporosis in Clinical Practice Study Group (2006) Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 17:914–921

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA, Silverman S (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgstrom F, Herings RM, Silverman SL (2009) Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med 122:S3–S13

Cotte FE, De Pouvourville G (2011) Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res 11:151

Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud K, Tosteson AN, Varon SF, Anthony M, Daizadeh N, Wade S (2009) Design of the POSSIBLE US™ study: postmenopausal women’s compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications. Osteoporos Int 20:463–472

Tosteson AN, Do TP, Wade SW, Anthony MS, Downs RW (2010) Persistence and switching patterns among women with varied osteoporosis medication histories: 12-month results from POSSIBLE US. Osteoporos Int 21:1769–1780

Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR (2004) Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcome 2:12

Brooks R (1996) EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 37:53–72

Randell AG, Bhalerao N, Nguyen TV, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA, Silverman SL (1998) Quality of life in osteoporosis: reliability, consistency, and validity of the Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire. J Rheumatol 25:1171–1179

Lee S, Glendenning P, Inderjeeth CA (2011) Efficacy, side effects and route of administration are more important than frequency of dosing of anti-osteoporosis treatments in determining patient adherence: a critical review of published articles from 1970 to 2009. Osteoporos Int 22:741–753

Silverman S, Calderon A, Kaw K, Childers TB, Stafford BA, Brynildsen W, Focil A, Koenig M, Gold DT (2013) Patient weighting of osteoporosis medication attributes across racial and ethnic groups: a study of osteoporosis medication preferences using conjoint analysis. Osteoporos Int 24:2067–2077

Li L, Roddam A, Gitlin M, Taylor A, Shepherd S, Shearer A, Jick S (2012) Persistence with osteoporosis medications among postmenopausal women in the UK General Practice Research Database. Menopause 19:33–40

Gold DT, Martin BC, Frytak JR, Amonkar MM, Cosman F (2007) A claims database analysis of persistence with alendronate therapy and fracture risk in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 23:585–594

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Ziller V, Wetzel K, Kyvernitakis I, Seker-Pektas B, Hadji P (2011) Adherence and persistence in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with raloxifene. Climacteric 14:228–235

Vanelli M, Pedan A, Liu N, Hoar J, Messier D, Kiarsis K (2009) The role of patient inexperience in medication discontinuation: a retrospective analysis of medication nonpersistence in seven chronic illnesses. Clin Ther 31:2628–2652

McHorney CA, Gadkari AS (2010) Individual patients hold different beliefs to prescription medications to which they persist vs nonpersist and persist vs nonfulfill. Patient Prefer Adherence 4:187–195

McHorney CA, Schousboe JT, Cline RR, Weiss TW (2007) The impact of osteoporosis medication beliefs and side-effect experiences on non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Curr Med Res Opin 23:3137–3152

Cadarette SM, Solomon DH, Katz JN, Patrick AR, Brookhart MA (2011) Adherence to osteoporosis drugs and fracture prevention: no evidence of healthy adherer bias in a frail cohort of seniors. Osteoporos Int 22:943–954

Curtis JR, Yun H, Lange JL, Matthews R, Sharma P, Saag KG, Delzell E (2012) Does medication adherence itself confer fracture protection? An investigation of the healthy adherer effect in observational data. Arthritis Care Res 64:1855–1863

Silverman SL, Gold DT (2011) Healthy users, healthy adherers, and healthy behaviors? J Bone Miner Res 26:681–682

Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Dormuth C, Avorn J, Shrank W, Cadarette SM, Solomon DH (2007) Adherence to lipid-lowering therapy and the use of preventive health services: an investigation of the healthy user effect. Am J Epidemiol 166:348–354

Dormuth CR, Patrick AR, Shrank WH, Wright JM, Glynn RJ, Sutherland J, Brookhart MA (2009) Statin adherence and risk of accidents: a cautionary tale. Circulation 119:2051–2057

Dublin S, Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, Larson EB, Jackson LA (2009) Statin use and risk of community acquired pneumonia in older people: population based case–control study. BMJ 338:b2137

Anon (2010) Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 17:25–54

Balasubramanian A, Brookhart MA, Goli V, Critchlow CW (2013) Discontinuation and reinitiation patterns of osteoporosis treatment among commercially insured postmenopausal women. Int J Gen Med 6:839–848

Ringe JD, Moller G (2009) Differences in persistence, safety and efficacy of generic and original branded once weekly bisphosphonates in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results of a retrospective patient chart review analysis. Rheumatol Int 30:213–221

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the POSSIBLE US™ Steering Committee: Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, Robert Downs, Ted Ganiats, Marc Hochberg, Barbara Lukert, Robert Recker, Robert Rubin, and Anna Tosteson. We would also like to thank Aalok Nadkar and Patrick Ventura for data analysis assistance and Mandy Suggitt of Amgen Inc. who provided editorial assistance. Funding for this study was provided by Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

Financial support

This study was funded by Amgen Inc.

Conflicts of interest

This study was funded by Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, whose employees were also involved in design of the study, interpretation of results, and development of the manuscript. Mandy Suggitt of Amgen Inc. provided editing assistance. Bradley Stolshek is an employee of Amgen Inc. and has received Amgen stock and stock options. Sacha Satram-Hoang and Sally Wade provide paid consulting services to Amgen Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wade, S.W., Satram-Hoang, S. & Stolshek, B.S. Long-term persistence and switching patterns among women using osteoporosis therapies: 24- and 36-month results from POSSIBLE US™. Osteoporos Int 25, 2279–2290 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2762-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2762-x