Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Patients presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) may report a history of sexual abuse (SA), and survivors of SA may report LUTS; however, the nature of the relationship is poorly understood. The aim of this review is to systematically evaluate studies that explore LUT dysfunction in survivors of SA.

Methods

A systematic literature search of six databases, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO, was performed. The last search date was June 2021 (PROSPERO CRD42019122080). Studies reporting the prevalence and symptoms of LUTS in patients who have experienced SA were included. The literature was appraised according to the PRISMA statement. The quality of the studies was assessed.

Results

Out of 272 papers retrieved, 18 publications met the inclusion criteria: studies exploring LUTS in SA survivors (n=2), SA in patients attending clinics for their LUTs (n=8), and cross-sectional studies (n=8). SA prevalence ranged between 1.3% and 49.6%. A history of SA was associated with psychosocial stressors, depression, and anxiety. LUTS included urinary storage symptoms, voiding difficulties, voluntary holding of urine and urinary tract infections. Most studies were of moderate quality. Assessment of SA and LUTS lacked standardisation.

Conclusions

The review highlights the need for a holistic assessment of patients presenting with LUTS. Although most of the studies were rated as being of ‘moderate’ quality, the evidence suggests the need to provide a “safe space” in clinic for patients to share sensitive information about trauma. Any such disclosure should be followed up with further assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attempted or executed sexual abuse (SA) conducted without consent from the victim can involve penetrative or non-penetrative acts and non-contact [1]. The perpetrator of abuse can range from being a complete stranger to someone familiar to the victim [2] and acts can be committed in private or in public spaces. The prevalence of SA is largely underestimated; however, the results of a recent survey suggests that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 59 men have been exposed to an attempted or completed act of rape during their lifetime [2]. Rates of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) can vary: between 2% and 62% of females and between 3% and 16% of males [3]. The reason for underreporting by victims are manifold, and can include feelings of shame, fear and guilt, a risk of retaliation by the perpetrator [4] and a lack of awareness that forced sexual acts constitute SA [5].

Abuse can have a profound impact on victims, ranging from reduced global functioning levels to lengthened trauma-related symptoms and an increased risk of developing substance abuse [6]. Both male and female victims can report increased rates of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [7]. Multiple physical and psychological sequelae have been reported, including anxiety, anger, depression, re-victimisation, self-mutilation, sexual difficulties, substance abuse, suicidality, impairment of self-concept, interpersonal problems, obsessions and compulsions, dissociation and post-traumatic stress responses to somatisation characterised by medically unexplained symptoms [7,8,9,10,11].

Somatisation, functional neurological symptoms and other medically unexplained symptoms can lead to repeated consultations and help-seeking behaviour, which can have significant financial implications in terms of use of health care resources and receipt of financial assistance [12]. Abuse occurring in childhood before the age of 17 (CSA) can result in multiple long-term consequences such as depression, anxiety, poor physical health and risky health behaviours [13]. Furthermore, CSA has been found to be significantly associated with poor outcomes when treating conversion disorders/functional neurological disorder [14].

Urological symptoms are likely to be common amongst survivors of SA. A Dutch study suggested that 2.1% of men and 13% of women seeking urological care may report SA [15]. Many of the physical and psychological sequelae of CSA were found to persist into adulthood [16] and up to one-third of patients attending a gynaecology clinic had experienced CSA [17, 18]. Victims of CSA younger than 6 years old most commonly reported urinary tract infections, daytime incontinence and nocturnal enuresis [19]. SA is likely to be underreported and in the Dutch study, only 15% of participants with a history of SA had disclosed this to their urologist [15]. In a study across five Nordic countries, most women did not disclose a history of SA to their gynaecologist [17]. Seventy percent of Dutch urologists enquired about SA when taking the medical history [20]; however, enquiry rates may vary across specialities and different health care settings.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 studies has demonstrated a significant association between a history of sexual assault and developing different gynaecological disorders such as pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, abnormal menstrual bleeding and urinary incontinence later in life [21]; however, lower urinary tract dysfunction was not specifically evaluated.

The relationship between SA and LUT dysfunction, however, has been poorly understood. The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the reported prevalence of SA, pattern of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and explore possible associations between SA and LUT dysfunction.

Materials and methods

The systematic review conformed to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement and the protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42019122080). A literature search was performed in December 2018 and updated in June 2021 for studies published in the English language without date restrictions in the following databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO. The same search strategy (i.e. keywords and inclusion and exclusion criteria) was used for all the databases. The following key words were used: “sexual dysfunction” OR “sexual abuse” OR “adult sexual abuse” OR “sexual trauma” OR “childhood sexual abuse” OR “CSA” OR “sexual maltreatment” OR “rape” OR “sexual offences” OR “sexual harassment” OR “sexual harm” OR “urinary tract” OR “urologist” OR “urological dysfunction” OR “urological symptoms” OR “LUTS” OR “lower urinary tract symptoms” OR “lower urinary tract problems” OR “uroneurology” OR “urethral” OR “genitourinary” OR “urinary frequency” OR “urgency” OR “urinary infection” AND “treatment” OR “management” OR “symptoms”.

Abstracts were imported into bibliography management software (EndNote X8; Thomson Reuters, PA, USA) and were independently evaluated by two reviewers (NS and SH). Studies relevant to the review reporting the prevalence and symptoms of LUTS in male and female patients who have experienced SA were included, whereas experimental studies in animals and studies primarily assessing interstitial cystitis, bladder pain syndrome and pain were excluded. The results of the two reviewers were compared and consensus was achieved by discussion; unresolved differences were reviewed independently (JNP).

Accepted abstracts were retrieved in full text and assessed by the two reviewers (NS and SH), and the following variables were assessed: setting and nature of cohort, definition of SA, assessment of SA, nature of abuse, other types of abuse, nature of LUTS, assessment of LUTS, diagnostic LUTS test and findings, and other co-morbidities. The quality of the studies and risk of bias were assessed using the assessment tool for quantitative studies by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) [22]. Each section was rated by the two reviewers and any discrepancies between scores were discussed and reconciled.

Results

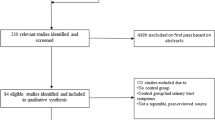

The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 272 studies were retrieved, and 18 studies met the inclusion criteria: studies exploring LUTS in SA survivors (n=2), studies exploring SA in patients attending clinics for their LUTS (n=8), and large cross-sectional studies evaluating different health issues including SA and LUTS (n=8). The majority of studies were prospective questionnaire-based cross-sectional studies (n=13; see Tables 1, 2 and 3). One study was a case–control study [23] and one was longitudinal [24]. The other studies were retrospective, cross-sectional in nature (n=3). Fourteen studies were conducted in the US [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], 2 in Germany [37, 38], 1 in the Netherlands [39] and 1 in Hong Kong [40].

Studies exploring LUTS in survivors of sexual assault

Table 1 summarises the results of two studies [25, 39]. SA was assessed using a non-validated questionnaire including questions about inappropriate unwanted sexual behaviours experienced before the age of 16 [25] or not reported [39]. LUTS were assessed using either a non-validated [25] or validated (Amsterdam Hyperactive Pelvic Floor Scale Women) [39] questionnaire.

Studies exploring SA in patients attending clinics for their LUTS

Table 2 summarises the results of these studies [23, 24, 26,27,28,29, 37, 40]. Four studies used validated scales to assess LUTS: UDI-6 [23, 24, 26, 29], IIQ-7 [24, 26, 29], OABq-SF [23] or a battery of questionnaires (ICIQ-UI, ICIQ-OAB, OABq, USS) [29]. Four studies used non-validated scales or other methods [27, 28, 37, 40].

The prevalence of reported SA ranged from 1.3% [40] to 49.6% [26]. Rates of trauma were significantly higher in patients with LUTS than in control subjects in six studies [23, 24, 26, 29, 37, 40]. SA was assessed using validated scales in three studies: Childhood Traumatic Events Scale and Recent Traumatic Events Scale [29], Modified Abuse Assessment Screen [28], Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Scheme BRFSS-ACE Module [23], a non-validated questionnaire [37], a modified previous survey [27], and by a single question [26,27,28]. The definition of SA differed according to study and included forced sexual activity [27, 40], childhood traumatic events occurring prior to age 17 [29], unwanted sexual activity [28], unwanted sexual touching, forced unwanted sexual touching and forced sex during childhood [23]. A precise definition—complete sexual penetration of the vagina, mouth or rectum without a women’s consent, involving the use of force or threat of harm—was used in only one study ([24]. SA was not defined in two studies [26, 37].

Large cross-sectional studies evaluating different health issues including SA and LUTS

Table 3 summarises the results of these studies [30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38]. SA was assessed using different methods and only one study used a validated questionnaire, The Childhood Traumatic Events Scale [36]. The prevalence of SA varied greatly between studies, from 9% [33] to 52.5% [38]. A total of 11.4% reported CSA and 39.2% reported an unwanted first sexual experience [35]. The prevalence of CSA was 21.6% and SA in adolescence/adulthood was reported to be 19.5% [30]; 25% (n=127) of women and 8% of men (n=38) reported traumatic sexual experience [36]. LUTS were assessed using validated questionnaires in only three studies: OABq-SF, PFDI-20; POPDI-6, UDI-6 [31], UDI-6 [32], the LUTS tool and the PFDI-20 [36].

Assessment of quality of included studies

Using the EPHPP assessment tool, the quality of five studies were rated “weak” [24, 25, 28, 32, 38], 12 studies were rated “moderate” [23, 26, 27, 29,30,31, 33, 35,36,37, 39, 40] and only one study was rated “strong” (Fig. 2) [34].

Discussion

In this review we present a synthesis of 18 studies that explore LUTS in survivors of SA. The wide prevalence of abuse across studies reflects differences in the cohorts studied and heterogeneity in definitions and study designs used. Most studies defined SA broadly as forced or unwanted sexual activity, ranging from the broadest, “unwanted sexual touching” [23] to the narrowest, “complete sexual penetration of the vagina, mouth or rectum without a women’s consent, involving the use of force or threat of harm” [24]. Furthermore, only four studies used a validated scale to assess SA [23, 29, 36, 40], which limited the extent to which the nature, length and severity of abuse could be assessed. The wide prevalence range of SA reported in the studies, from 1.3% [40] to 49.6% [28] may not accurately reflect the true prevalence of SA in patients reporting with LUTS; however, it is somewhat in keeping with the prevalence reported in other cohorts without LUTS [41, 42].

Because of the sensitive nature of SA, there were limits to the extent to which patients could be approached by health care professionals about possible SA. Only 66% of women with pelvic floor disorders were asked about SA [21], whereas in a study exploring physical and SA in patients with an overactive bladder, only women who were not accompanied by a male were approached because of concerns regarding safety [37]. Clinicians would have been reluctant to enquire about SA owing to assumptions that patients may react negatively when questioned [43], lack of familiarity with how to enquire and/or uncertainty about how to proceed if a patient were to disclose SA [20]. In a survey of survivors, more than 70% of abused respondents favourably considered the idea of screening for SA in urological practice [15]. However, patients may not be readily prepared to engage, and over 20% of participants in a study exploring interpersonal trauma and genitourinary dysfunction did not disclose information about sexual assault, more commonly African American and non-partnered women [33]. In a study of Chinese women, which reported the highest response rate of 96%, only 1.3% reported SA and cultural factors of shame and stigma were possible factors responsible for underreporting [40]. Other reasons could include recall bias, disquiet in a public hospital setting, wording of questions about SA and concerns regarding confidentiality.

Lower urinary tract symptoms were variably assessed and urinary storage problems such as urinary incontinence, frequency and nocturia were reported most often. Some patients were reporting incontinence in the context of holding the urine too long until it became painful [25]. Urodynamics testing was not performed in any of the studies. The cause of urinary incontinence was unclear and inclusion of validated questionnaires and possibly urodynamics in future studies would help to understand whether incontinence was due to overactive bladder, stress incontinence or mixed. Establishing dysfunction such as bladder hypersensitivity and/or detrusor overactivity would be critical when tailoring therapeutic strategies for managing these symptoms [44]. Voiding difficulties were less often reported and symptoms reported were pain with urination, hesitancy, slow stream, dribbling, holding urine until painful, incomplete bladder emptying, weak urinary stream and straining to begin urination [25, 33]. Questionnaires such as the UDI-6 do specifically enquire about voiding difficulties; however, only the total score was reported in studies. Urinary retention was not reported and post-void residual volumes were not measured in any of the studies; therefore, the extent of incomplete bladder emptying could not be assessed. Although trauma features in the history of patients presenting with idiopathic urinary retention in men and women [45,46,47], none of the studies in this review specifically explored urinary retention related to sexual trauma.

Sexual trauma may be one of different types of abuses suffered by individuals, and in these studies emotional and physical abuse [23, 26], violence [29], physical abuse [27, 37], and domestic violence, verbal and physical abuse [40] were reported. Whether other types of abuse contribute to the occurrence of LUT dysfunction is unclear, as an association between emotional abuse and voiding difficulties [35] and urinary incontinence [33] have been reported. Limitations to study designs precluded any meaningful exploration of the association of these different types of abuse with the occurrence of LUTS. The association between trauma and functional somatic syndromes is well established [48, 49] and the stressor response occurring following trauma has been shown to result in physiological changes in body and brain functions that can persist through life and predispose individuals to a range of physical and psychological sequelae.

The age at which SA occurs is also significant; SA occurring during critical developmental periods has been shown to result in profound endocrinological and immunological consequences that may have long-term effects on an individual’s ability to react and respond to illness [50]. Somatic problems such as musculoskeletal pain, ear, nose, and throat symptoms, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and dizziness have been found to be more common in adults with a history of childhood trauma than in non-traumatised counterparts [10]. These subjective, medically unexplained physical health problems often persist and present as functional somatic syndromes such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue/pain, and irritable bowel syndrome [51]. A recent study found that complex PTSD symptoms mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and trauma and physical health problems. Complex PTSD is associated with a number of psychological sequelae, including hypervigilance, anxiety, agitation, dissociation [52], anger, aggression, self-harm [53], dysregulation in emotion processing, self-organisation (including bodily integrity), relational functioning [54], and psychological interventions that effectively treat symptoms may additionally reduce the risk of physical health problems [55]. Urological symptoms such as OAB are associated with a number of psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety and CSA [56].

It is likely, however, that there are different mechanisms responsible for LUTS in survivors of SA. Physical trauma to the perineum and pelvis [57, 58] can result in damage to the regional anatomy. Studies have shown an association between LUTS and anxiety, depression [59,60,61,62] and PTSD [63]. Neurobiological mechanisms implicate corticotrophin-releasing factor and serotonergic and dopaminergic systems in the pathogenesis of mood disorders and PTSD, and possible links with LUTS. There is a possibility that adverse life events may lead to neurobiological and physiological changes that increase the risk of both mood disorders and somatic disorders, but that the risk factors may be different [64]. Somatisation may be an adaptive response to psychological distress [65] and although specific symptoms linked to SA have not been consistently identified [66], it is plausible that LUTS may be associated with complex PTSD and a manifestation of somatisation linked to SA; however, this needs to be further explored. Some clinical teams, acknowledging the challenges, are highlighting the need for a multi-disciplinary approach [67]. Notably, duloxetine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), that is well established in the treatment of depression and anxiety, has been used with success in the management of both OAB and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) [68, 69].

There were some limitations to this review. Few studies were relevant to the topic, and the overall quality was “moderate”. In the absence of an operational definition for SA, the cohorts differed between studies. Furthermore, a standardised assessment was lacking and therefore the extent of details about types of abuse and their frequency, relationship to the perpetrator, time-frame of abuse, age and impact on childhood development were often missing. A challenge for any research in this area is recall bias, and the wording used in the enquiry about SA and also the setting differed between studies. The extent of rapport and trust between health care professionals and the participants was not assessed; however, these would be critical when exploring such a sensitive topic. Bias in sampling resulting from poor response rates amongst participants approached was not addressed in any of the studies. The assessment of LUTS also differed considerably between studies and therefore the true extent and pattern of LUT dysfunction could not be assessed. Nonetheless, it can be concluded that there exists an association between SA and urinary storage and voiding symptoms.

One major limitation of the review is the low quality and low level of evidence of these 18 studies. Also, the EPHPP does not explore characteristics from each study design that other quality tools can do, such as the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [70]. There is a need for further research to explain the relation between SA and LUTS. Further, as the studies included in this review were too heterogeneous, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Treatment options, which should take a multi-disciplinary approach, were outside the scope of this review, but, drawing on the current published evidence of treatments for PTSD and complex PTSD, we hypothesise that a proportion of these patients may be helped by trauma-focussed cognitive behavioural therapy and/or other psychotherapeutic interventions.

Conclusion

The review highlights the need to provide a holistic assessment of patients presenting with LUTS that includes standardised screening for SA in a “safe space” for patients to share sensitive information, and screening for concurrent inter-related factors such as trauma, affective symptoms and somatisation which can impact LUTS. Well-designed studies are required to explore what impact such an assessment may have on the management of LUTS.

References

Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, Smith C, Schreyer JK, Trickett PK. Characterizing the sexual abuse experiences of young adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(2):261–70.

Breiding MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):e11–e12.

Johnson CF. Child sexual abuse. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):462–70.

Sable MR, Danis F, Mauzy DL, Gallagher SK. Barriers to reporting sexual assault for women and men: perspectives of college students. J Am Coll Heal. 2006;55(3):157–62.

Holmes WC. Men’s self-definitions of abusive childhood sexual experiences, and potentially related risky behavioral and psychiatric outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(1):83–97..

Ruch LO, Amedeo SR, Leon JJ, Gartrell JW. Repeated sexual victimization and trauma change during the acute phase of the sexual assault trauma syndrome. Women Health. 1991;17(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v17n01_01.

Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. J Psychol. 2001;135(1):17–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980109603677.

Subica AM. Psychiatric and physical sequelae of childhood physical and sexual abuse and forced sexual trauma among individuals with serious mental illness. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):588–96.

Leserman J. Sexual abuse history: prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):906–15.

Nelson S, Baldwin N, Taylor J. Mental health problems and medically unexplained physical symptoms in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse: an integrative literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19(3):211–20.

Walker JL, Carey PD, Mohr N, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Gender differences in the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and in the development of pediatric PTSD. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(2):111–21.

Allanson J, Bass C, Wade DT. Characteristics of patients with persistent severe disability and medically unexplained neurological symptoms: a pilot study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(3):307–9.

Neumann DA, Houskamp BM, Pollock VE, Briere J. The long-term sequelae of childhood sexual abuse in women: a meta-analytic review. Child Maltreat. 1996;1(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559596001001002.

Van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Allen SF, Eck V, van der Sluijs JF. Childhood sexual abuse predicts treatment outcome in conversion disorder/functional neurological disorder. An observational longitudinal study. Brain Behav. 2020;10(3):e01558.

Beck JJH, Bekker MD, van Driel MF, Roshani H, Putter H, Pelger RCM, et al. Prevalence of sexual abuse among patients seeking general urological care. J Sex Med. 2011;8(10):2733–8.

Warlick CA, Mathews R, Gerson AC. Keeping childhood sexual abuse on the urologic radar screen. Urology. 2005;66(6):1143–9.

Wijma B, Schei B, Swahnberg K, Hilden M, Offerdal K, Pikarinen U, et al. Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in patients visiting gynaecology clinics: a Nordic cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2003;361(9375):2107–13.

Kaliray P, Drife J. Childhood sexual abuse and subsequent gynaecological conditions. Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;6(4):209–14.

Ellsworth P, Merguerian P, Copening M. Sexual abuse. J Urol. 1995;153:773–6.

Beck J, Bekker M, Van Driel M, et al. Female sexual abuse evaluation in the urological practice: results of a Dutch survey. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1464–8.

Hassam T, Kelso E, Chowdary P, Yisma E, Mol BW, Han A. Sexual assault as a risk factor for gynaecological morbidity: an exploratory systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:222–30.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

Komesu YM, Petersen TR, Krantz TE, Ninivaggio CS, Jeppson PC, Meriwether KV, et al. Adverse childhood experiences in women with overactive bladder or interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(1):e208–14.

Bradley CS, Nygaard IE, Torner JC, Hillis SL, Johnson S, Sadler AG. Overactive bladder and mental health symptoms in recently deployed female veterans. J Urol. 2014;191(5):1327–32.

Davila GW, Bernier F, Franco J, Kopka SL. Bladder dysfunction in sexual abuse survivors. J Urol. 2003;170(2 Pt 1):476–9.

Klausner AP, Ibanez D, King AB, Willis D, Herrick B, Wolfe L, et al. The influence of psychiatric comorbidities and sexual trauma on lower urinary tract symptoms in female veterans. J Urol. 2009;182(6):2785–90.

Lutgendorf MA, Snipes MA, O’Boyle AL. Prevalence and predictors of intimate partner violence in a military urogynecology clinic. Mil Med. 2017;182(3):e1634–8.

Cichowski SB, Dunivan GC, Komesu YM, Rogers RG. Sexual abuse history and pelvic floor disorders in women. South Med J. 2013;106(12):675–8.

Lai HH, Morgan CD, Vetter J, Andriole GL. Impact of childhood and recent traumatic events on the clinical presentation of overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(8):1017–23.

Link CL, Lutfey KE, Steers WD, McKinlay JB. Is abuse causally related to urologic symptoms? Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52(2):397–406.

Nault T, Gupta P, Ehlert M, Dove-Medows E, Seltzer M, Carrico DJ, et al. Does a history of bullying and abuse predict lower urinary tract symptoms, chronic pain, and sexual dysfunction? Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48(11):1783–8.

Bradley CS, Nygaard IE, Hillis SL, Torner JC, Sadler AG. Longitudinal associations between mental health conditions and overactive bladder in women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(4):430.e1–8.

Gibson CJ, Lisha NE, Walter LC, Huang AJ. Interpersonal trauma and aging-related genitourinary dysfunction in a national sample of older women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):94.e1–7.

Boyd BAJ, Gibson CJ, Van Den Eeden SK, McCaw B, Subak LL, Thom D, et al. Interpersonal trauma as a marker of risk for urinary tract dysfunction in midlife and older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(1):106–12.

Lalchandani P, Lisha N, Gibson C, Huang AJ. Early life sexual trauma and later life genitourinary dysfunction and functional disability in women. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3210–7.

Geynisman-Tan J, Helmuth M, Smith AR, Lai HH, Amundsen CL, Bradley CS, et al. Prevalence of childhood trauma and its association with lower urinary tract symptoms in women and men in the LURN study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40(2):632–41.

Jundt K, Scheer I, Schiessl B, Pohl K, Haertl K, Peschers UM. Physical and sexual abuse in patients with overactive bladder: is there an association? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):449–53.

Mark H, Bitzker K, Klapp BF, Rauchfuss M. Gynaecological symptoms associated with physical and sexual violence. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29(3):164–72.

Postma R, Bicanic I, van der Vaart H, Laan E. Pelvic floor muscle problems mediate sexual problems in young adult rape victims. J Sex Med. 2013;10(8):1978–87.

Ma WSP, Pun TC. Prevalence of domestic violence in Hong Kong Chinese women presenting with urinary symptoms. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159367.

Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(4):328–38.

Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16(2):79–101.

Peschers UM, Mont JD, Jundt K, Pfürtner M, Dugan E, Kindermann G. Prevalence of sexual abuse among women seeking gynecologic care in Germany. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(1):103–8.

Peyronnet B, Mironska E, Chapple C, Cardozo L, Oelke M, Dmochowski R, et al. A comprehensive review of overactive bladder pathophysiology: on the way to tailored treatment. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):988–1000.

Williams GE, Johnson AM. Recurrent urinary retention due to emotional factors; report of a case. Psychosom Med. 1956;18(1):77–80.

Von Heyden B, Steinert R, Bothe HW, Hertle L. Sacral neuromodulation for urinary retention caused by sexual abuse. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(3):505–8.

Selai C, Pakzad M, Simeoni S, Joyce E, Petrochilos P, Panicker J. Psychological co-morbidities in young women presenting with chronic urinary retention. 2019. Available from: https://www.ics.org/2019/abstract/705

Kugler BB, Bloom M, Kaercher LB, Truax TV, Storch EA. Somatic symptoms in traumatized children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(5):661–73.

Bonvanie IJ, van Gils A, Janssens KAM, Rosmalen JGM. Sexual abuse predicts functional somatic symptoms: an adolescent population study. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;46:1–7.

Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(1):29–39.

Mayou R, Farmer A. Functional somatic symptoms and syndromes. BMJ. 2002;325(7358):265–8.

Herman J. Complex PTSD: a syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5:377–91.

Dyer KFW, Dorahy MJ, Hamilton G, Corry M, Shannon M, MacSherry A, et al. Anger, aggression, and self-harm in PTSD and complex PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(10):1099–114.

Ford JD. Complex PTSD: research directions for nosology/assessment, treatment, and public health. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:27584.

Ho GWK, Karatzias T, Vallières F, Bondjers K, Shevlin M, Cloitre M, et al. Complex PTSD symptoms mediate the association between childhood trauma and physical health problems. J Psychosom Res. 2021;142:110358.

Dolat M, Klausner A. UROPSYCHIATRY: the relationship between overactive bladder and psychiatric disorders. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2012;8:69–76.

Kim K, Nam J, Choi B, et al. The association of lower urinary tract symptoms with incidental falls and fear of falling in later life: The Community Health Survey. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;37:775–84.

Owusu Sekyere E, Hardcastle T, Sathiram R, et al. Overview of lower urinary tract symptoms post-trauma intensive care unit admission. Afr J Urol. 2020;26:1–7.

Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103(Suppl 3):4–11.

Yang YJ, Koh JS, Ko HJ, Cho KJ, Kim JC, Lee S-J, et al. The influence of depression, anxiety and somatization on the clinical symptoms and treatment response in patients with symptoms of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Aug;29(8):1145–51.

Lung-Cheng Huang C, Ho C-H, Weng S-F, Hsu Y-W, Wang J-J, Wu M-P. The association of healthcare seeking behavior for anxiety and depression among patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: a nationwide population-based study. Psychiatry Res. 2015;226(1):247–51.

Vrijens D, Drossaerts J, van Koeveringe G, Van Kerrebroeck P, van Os J, Leue C. Affective symptoms and the overactive bladder—a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(2):95–108.

Breyer BN, Cohen BE, Bertenthal D, Rosen RC, Neylan TC, Seal KH. Lower urinary tract dysfunction in male Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans: association with mental health disorders: a population-based cohort study. Urology. 2014;83(2):312–9.

Epperson CN, Duffy KA, Johnson RL, Sammel MD, Newman DK. Enduring impact of childhood adversity on lower urinary tract symptoms in adult women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(5):1472–81.

Bae SM, Kang JM, Chang HY, Han W, Lee SH. PTSD correlates with somatization in sexually abused children: Type of abuse moderates the effect of PTSD on somatization. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199138.

Iloson C, Moller A, Sundfeldt A, Bernhardsson S. Symptoms within somatisation after sexual abuse among women: a scoping review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:758–67.

Cour F, Robain G, Claudon B, Chartier-Kästler E. Childhood sexual abuse: how important is the diagnosis to understand and manage sexual, anorectal and lower urinary tract symptoms. Prog Urol. 2013;23(9):780–92.

Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Lange RR, Jonasson AF, Chen WJ, Viktrup L. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in elderly women with stress urinary incontinence or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence. Maturitas. 2008;60(2):138–47.

Cardozo L, Lange R, Voss S, Beardsworth A, Manning M, Viktrup L, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy and safety of duloxetine in women with predominant stress urinary incontinence. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(2):253–61.

Wells G, Brodsky L, O’Connell D, Shea B, Henry D, Mayank S, Tugwell P. XI Cochrane Colloquium: evidence, health care and culture. Barcelona, Spain; 2003. Evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS): an assessment tool for evaluating the quality of non-randomized studies. http://www.citeulike.org/user/SRCMethodsLibrary/article/12919189.

Acknowledgements

J.N. Panicker is supported in part by funding from the United Kingdom’s Department of Health NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Selai: protocol/project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing; M. Elmalem: protocol/project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing; E. Chartier-Kästler: protocol/project development, data collection or management, manuscript writing/editing; N. Sassoon: data collection or management, data analysis; S. Hewitt: data collection or management, data analysis; M.F. Rocha: data collection or management, data analysis; L. Klitsinari: data collection or management, data analysis; J.N. Panicker: protocol/project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

J.N.P has received honoraria from Novartis, Coloplast, Allergan, Idorsia and Wellspect and royalties for book editing from Cambridge University Press. He has no disclosures related to this work. E.C.-K. has received honoraria from Coloplast, Allergan, Medtronic, Convatec, B Braun, Boston Scientific, Promedon, Uromems. He has no disclosures related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Selai, C., Elmalem, M.S., Chartier-Kastler, E. et al. Systematic review exploring the relationship between sexual abuse and lower urinary tract symptoms. Int Urogynecol J 34, 635–653 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05277-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05277-4