Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The protocol and analysis methods for the Defining Mechanisms of Anterior Vaginal Wall Descent (DEMAND) study are presented. DEMAND was designed to identify mechanisms and contributors of prolapse recurrence after two transvaginal apical suspension procedures for uterovaginal prolapse.

Methods

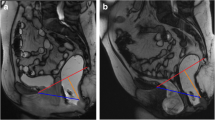

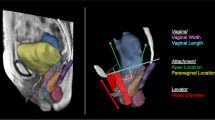

DEMAND is a supplementary cohort study of a clinical trial in which women with uterovaginal prolapse randomized to (1) vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension or (2) vaginal mesh hysteropexy underwent pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 30–42 months post-surgery. Standardized protocols have been developed to systematize MRI examinations across multiple sites and to improve reliability of MRI measurements. Anatomical failure, based on MRI, is defined as prolapse beyond the hymen. Anatomic measures from co-registered rest, maximal strain, and post-strain rest (recovery) sequences are obtained from the “true mid-sagittal” plane defined by a 3D pelvic coordinate system. The primary outcome is the mechanism of failure (apical descent versus anterior vaginal wall elongation). Secondary outcomes include displacement of the vaginal apex and perineal body and elongation of the anterior wall, posterior wall, perimeter, and introitus of the vagina between (1) rest and strain and (2) rest and recovery.

Results

Recruitment and MRI trials of 94 participants were completed by May 2018.

Conclusions

Methods papers which detail studies designed to evaluate anatomic outcomes of prolapse surgeries are few. We describe a systematic, standardized approach to define and quantitatively assess mechanisms of anatomic failure following prolapse repair. This study will provide a better understanding of how apical prolapse repairs fail anatomically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- DEMAND:

-

Defining Mechanisms of Anterior Vaginal Wall Descent

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- POP:

-

Pelvic organ prolapse

- NTR:

-

Native tissue repair

- VM:

-

Transvaginal mesh

- POP-Q:

-

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification

- PFDN:

-

Pelvic Floor Disorders Network

- SUPeR:

-

Study of Uterine Prolapse Procedures Randomized

References

Digesu GA, Chaliha C, Salvatore S, Hutchings A, Khullar V. The relationship of vaginal prolapse severity to symptoms and quality of life. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(7):971–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00568.x.

Zielinski R, Miller J, Low LK, Sampselle C, Delancey JOL. The relationship between pelvic organ prolapse, genital body image, and sexual health. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(7):1145–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22205.

Handa VL, Cundiff G, Chang HH, Helzlsouer KJ. Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(5):1045–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816bbe85.

Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286.

Eilber KS, Alperin M, Khan A, et al. Outcomes of vaginal prolapse surgery among female medicare beneficiaries: the role of apical support. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):981–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a8a5e4.

Davila GW, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate: Consensus of the 2nd IUGA grafts roundtable: Optimizing safety and appropriateness of graft use in transvaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1677-3

Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311(10):1023–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.1719.

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Norton P, et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2018;319(15):1554–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2827.

Lykke R, Blaakær J, Ottesen B, Gimbel H. The indication for hysterectomy as a risk factor for subsequent pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(11):1661–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2757-y.

Jonsson Funk M, Edenfield AL, Pate V, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Wu JM. Trends in use of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(1):79.e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.008.

Maher CM, Feiner B, Baessler K, Glazener CMA. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: The updated summary version Cochrane review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1445–1457. Springer London. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1542-9.

Feiner B, Jelovsek JE, Maher C. Efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh kits in the treatment of prolapse of the vaginal apex: a systematic review. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(1):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02023.x.

Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, et al. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):230.e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.046.

FDA takes action to protect women’s health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices | FDA. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-action-protect-womens-health-orders-manufacturers-surgical-mesh-intended-transvaginal. Accessed 14 Jan 2020.

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al. Effect of vaginal mesh hysteropexy vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2019;322(11):1054–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.12812.

Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1323–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001.

Easley DC, Menon PG, Abramowitch SD, Moalli PA. Inter-observer variability of vaginal wall segmentation from MRI: a statistical shape analysis approach. In: ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Proceedings (IMECE). Vol 3–2015. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME); 2015. https://doi.org/10.1115/IMECE2015-53499.

Hoyte L, Brubaker L, Fielding JR, et al. Measurements from image-based three dimensional pelvic floor reconstruction: a study of inter- and intraobserver reliability. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(2):344–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.21847.

Tumbarello JA, Hsu Y, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Rohrer S, DeLancey JOL. Do repetitive Valsalva maneuvers change maximum prolapse on dynamic MRI? Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(10):1247–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1178-1.

Swenson CW, Luo J, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. Traction force needed to reproduce physiologically observed uterine movement: technique development, feasibility assessment, and preliminary findings. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(8):1227–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2980-1.

Kowalski JT, Mehr A, Cohen E, Bradley CS. Systematic review of definitions for success in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(11):1697–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3755-7.

Meister MRL, Sutcliffe S, Lowder JL. Definitions of apical vaginal support loss: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:232.e1–232.e14. Mosby Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.078

J.O. D. The hidden epidemic of pelvic floor dysfunction: achievable goals for improved prevention and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192(5):1488–1495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.014.

Kashihara H, Emmanuelli V, Poncelet E, et al. Comparison of dynamic MRI vaginal anatomical changes after vaginal mesh surgery and laparoscopic sacropexy. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(4):249–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-014-0864-2.

Kasturi S, Lowman J, Kelvin FM, Akisik F, Terry C, Hale DS. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of the efficacy of the Prolift system for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:504.e1–504.e5. Mosby Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.034

Arenholt LTS, Pedersen BG, Glavind K, Greisen S, Bek KM, Glavind-Kristensen M. Prospective evaluation of paravaginal defect repair with and without apical suspension: a 6-month postoperative follow-up with MRI, clinical examination, and questionnaires. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(10):1725–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3807-z.

Acknowledgments

Personnel

The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals from the following institutions: UC San Diego Health, San Diego, CA: Michael E. Albo, Marianna Alperin, Joann Columbo, Kimberly Ferrante, Kyle Herrala, Sherella Johnson, Anna C. Kirby, Emily S. Lukacz, Charles W. Nager, Erika Ruppert, Erika Wasenda. Kaiser Permanente-San Diego: Gouri B. Diwadkar, Keisha Y. Dyer, Linda M. Mackinnon, Shawn A. Menefee, Jasmine Tan-Kim, Gisselle Zazueta-Damian. Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Cindy Amundsen, Robin Gilliam, Acacia Harris, Akira Hayes, Amie Kawasaki, Nicole Longoria, Shantae McLean, Mary Raynor, Nazema Siddiqui, Anthony G. Visco. University of Alabama at Birmingham, Dept. OB/GYN, Birmingham, AL: Alicia Ballard, Kathy Carter, David Ellington, Robert L. Holley, Alice Howell, Jill Hyde, Ryanne Johnson, Alyssa Long, Lisa Pair, Sunita Patel, Nancy Saxon, R. Edward Varner, Robin Willingham, Velria Willis, Tracey Wilson. Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI: Cassandra Carberry, Samantha Douglas, B. Star Hampton, Nicole Korbly, Ann S. Meers, Deborah L. Myers, Vivian W. Sung, Elizabeth-Ann Viscione, Kyle Wohlrab. University of New Mexico: Karen Box, Sara Cichowski, Gena Dunivan, Peter Jeppson, Julia Middendorf, Rebecca G. Rogers. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA: Lily Arya, Uduak Andy, Teresa Carney, Lorraine Flick, Michelle Kingslee, Ariana Smith, Donna Thompson. Magee-Women’s Hospital, Dept. of OB/GYN & Reproductive Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA: Kate Amodei, Michael Bonidie, Judy Gruss, Jerry Lowder, Karen Mislanovich, Jonathan Shepherd, Gary Sutkin, Halina M. Zyczynski. Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH: Matthew Barber, Kathleen Dastoli, Maryori Edington, Annette Graham, Geetha Krishnan, Eric Jelovsek, Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, Ly Pung, Cecile Unger, Mark Walters. Northwest Texas Physician Group: Susan Meikle. Research Triangle International, Research Triangle Park, NC: Katrina Burson, Ben Carper, AnnaMarie Connelly, UNC, Tracey Davis, Tracey Grant, Emily Honeycutt, Kelly Koeller-Anna, Kendra Glass, James Pickett, Dennis Wallace, Ryan Whitworth.

Funding

This study was conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development-sponsored Pelvic Floor Disorders Network (PFDN Protocol: 24SP01). This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U10 HD054214, U10 HD041267, U10 HD041261, U10 HD069013, U10 HD069025, U10 HD069010, U10 HD069006, U10 HD054215, U01 HD069031) and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health. Research training support was given by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (5T32EB003392–13). Partial support for the PFDN DEMAND study is being supplied by Boston Scientific Corporation through a research grant to the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network Data Coordinating Center, RTI International. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Moalli, Pamela A.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Bowen, Shaniel T.: Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Abramowitch, Steven D.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Lockhart, Mark E.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Ham, Michael: Data collection/management, Manuscript writing/editing.

Hahn, Michael: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Weidner, Alison C.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Richter, Holly E.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Rardin, Charles R.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Komesu, Yuko M.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Harvie, Heidi S.: Protocol/project development, Data collection, Manuscript writing/editing.

Ridgeway, Beri M.: Data collection/management, Manuscript writing/editing.

Mazloomdoost, Donna: Protocol/project development, Manuscript writing/editing.

Shaffer, Amanda: Data collection/management, Manuscript writing/editing.

Gantz, Marie G.: Protocol/project development, Data collection/management, Data analysis, Manuscript writing/editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Pamela A. Moalli: Amphora Medical Inc., consulting; NICHD, research support;

Shaniel T. Bowen: None.

Steven D. Abramowitch: NICHD: research support;

Mark E. Lockhart: JUM, deputy editor, salary and editorial work; Elsevier, book royalties; Oxford Publishers, book royalties;

Michael Ham: None.

Michael E. Hahn: General Electric, research grant; HealthLytix, consultant;

Alison C. Weidner: OBGYN Survey, assistant editor, salary and editorial work; NICHD, research support; Urocure, consultant.

Holly E. Richter: IUJ, OG, editorial work and travel reimbursement; Worldwide Fistula Fund, board membership and travel reimbursement; American Urogynecologic Society, Board of Directors, travel reimbursement; Bluewind, DSMB; Renovia, Allergan, NICHD, NIA, research support; UpToDate, licensor and royalties;

Charles R. Rardin: FPMRS, editorial board membership; Solace Therapeutics, Pelvalon, Foundation for Female Health Awareness, NICHD, research support;

Yuko M. Komesu: Cook-Myosite®, funding; NICHD, funding.

Heidi S. Harvie: None.

Beri M. Ridgeway: Coloplast Corp, consulting, education, and travel & lodging;

Donna Mazloomdoost: Boston Scientific, research grant.

Amanda Shaffer: None.

Marie G. Gantz: Boston Scientific, research grant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

The following is a direct excerpt of a supplementary file from the parent study (SUPeR Trial) [15] that detailed its inclusion and exclusion criteria which was adopted by the DEMAND study:

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Women aged 21 or older who have completed child-bearing

-

2.

Prolapse beyond the hymen (defined as Ba, Bp, or C > 0 cm)

-

3.

Uterine descent into at least the lower half of the vagina [defined as point C > -TVL/2)]

-

4.

Bothersome bulge symptoms as indicated on question 3 of the PFDI-20 form relating to ‘sensation of bulging’ or ‘something falling out’

-

5.

Desires vaginal surgical treatment for uterovaginal prolapse

-

6.

Available for up to 60-month follow-up

-

7.

Amenorrhea for the past 12 months from either menopause or endometrial ablation

-

8.

Not pregnant, not at risk for pregnancy, or agree to contraception if at risk for pregnancy (only applicable to the rare endometrial ablation patient)

-

9.

Eligible for no cervical cancer screening for at least 3 years

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Previous synthetic material (placed vaginally or abdominally) to augment POP repair

-

2.

Known previous uterosacral or sacrospinous uterine suspension

-

3.

Known adverse reaction to synthetic mesh or biological grafts; these complications include but are not limited to erosion, fistula, or abscess

-

4.

Chronic pelvic pain

-

5.

Pelvic radiation

-

6.

Cervical elongation—defined as an expectation that the C point would be Stage 2 or greater postoperatively if a hysteropexy was performed. (Note: cervical shortening or trachelectomy is not an allowed intraoperative procedure within the hysteropexy treatment group).

-

7.

Women at increased risk of cervical dysplasia requiring cervical cancer screening more often than every 3 years [e.g., HIV+ status, immunosuppression because of transplant related medications, Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero, or previous treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)2, CIN3, or cancer]

-

8.

Uterine abnormalities (symptomatic uterine fibroids, polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, or any uterine disease that precluded prolapse repair with uterine preservation in the opinion of the surgeon)

-

9.

Indication for ovarian removal (adnexal mass, BRCA 1/2 positivity, family history of ovarian cancer)

-

10.

Current condition of amenorrhea caused by exogenous sex steroids or hypothalamic conditions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moalli, P.A., Bowen, S.T., Abramowitch, S.D. et al. Methods for the defining mechanisms of anterior vaginal wall descent (DEMAND) study. Int Urogynecol J 32, 809–818 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04511-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04511-1