Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

We sought to identify postoperative structural failure sites associated with long-term prolapse recurrence and their association with symptoms and satisfaction.

Methods

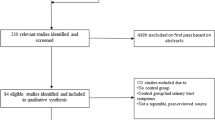

Women who had a research MRI prior to native-tissue prolapse surgery were recruited for examination, 3D stress MRI, and questionnaires. Recurrence was defined by Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q)Ba/Bp > 0 or C > -4. Measurements were performed at rest and maximum Valsalva (“strain”) including vaginal length, apex location, urogenital hiatus (UGH), and levator hiatus (LH). Measures were compared between subjects and to women with normal support. Failure frequency was the proportion of women with measurements outside the normal range. Symptoms and satisfaction were measured using validated questionnaires.

Results

Thirty-one women participated 12.7 years after surgery—58% with long-term success and 42% with recurrence. Failure site comparisons between success and failure were: impaired mid-vaginal paravaginal support (62% vs. 28%, p = 0.01), longer vaginal length (54% vs. 22%, p = 0.03), and enlarged urogenital hiatus (54% vs. 22%, p = 0.03). Apical paravaginal location had the lowest failure frequency (recurrence: 15% vs. success: 7%, p = 0.37). Patient satisfaction was high (recurrence: 5.0 vs. success: 5.0, p = 0.86). Women with bothersome bulge symptoms had a 33% larger UGH strain on POP-Q (p = 0.01), 8.7% larger resting UGH (p = 0.046), 11.5% larger straining LH (p = 0.01), and 9.3% larger resting LH (p = 0.01).

Conclusions

Abnormal low mid-vaginal paravaginal location (Level II), long vaginal length (Level II), and large UGH (Level III) were associated with long-term prolapse recurrence. Patient satisfaction was high and unrelated to anatomical recurrence. Bothersome bulge symptoms were associated with hiatus enlargement.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6.

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1455–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060.

Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Redden DT, Burgio KL, Richter HE, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):141–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057.

Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, Cundiff G, Richter H, Gantz M, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2016–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.4919.

Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Nygaard I, Weidner AC, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.1719.

Morgan DM, Larson K, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Fenner DE, DeLancey JO. Vaginal support as determined by levator ani defect status 6 weeks after primary surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114(2):141–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.02.020.

Berger MB, Kolenic GE, Fenner DE, Morgan DM, DeLancey JOL. Structural, functional, and symptomatic differences between women with rectocele versus cystocele and normal support. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(5):510.e511–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.033.

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–7.

Trowbridge ER, Fultz NH, Patel DA, DeLancey JO, Fenner DE. Distribution of pelvic organ support measures in a population-based sample of middle-aged, community-dwelling African American and white women in southeastern Michigan. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):548 e541–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.054.

Sung VW, Kauffman N, Raker CA, Myers DL, Clark MA. Validation of decision-making outcomes for female pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):575.e571–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.035.

Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):1388–95. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.118659.

Chen L, Lisse S, Larson K, Berger MB, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Structural failure sites in anterior Vaginal Wall prolapse: identification of a collinear triad. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):853–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001652.

Reiner CS, Williamson T, Winklehner T, Lisse S, Fink D, DeLancey JOL, et al. The 3D pelvic inclination correction system (PICS): a universally applicable coordinate system for isovolumetric imaging measurements, tested in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2017;59:28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compmedimag.2017.05.005.

Betschart C, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. On pelvic reference lines and the MR evaluation of genital prolapse: a proposal for standardization using the pelvic inclination correction system. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(9):1421–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2100-4.

Larson KA, Smith T, Berger MB, Abernethy M, Mead S, Fenner DE, et al. Long-term patient satisfaction with Michigan four-wall sacrospinous ligament suspension for prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):967–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a7f0d5.

Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Morlin B, Hammarstrom M. A 5-year prospective follow-up study of vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(12):1593–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0702-z.

Fialkow MF, Newton KM, Weiss NS. Incidence of recurrent pelvic organ prolapse 10 years following primary surgical management: a retrospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(11):1483–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0678-8.

Haylen BT, Avery D, Chiu TL, Birrell W. Posterior repair quantification (PR-Q) using key anatomical indicators (KAI): preliminary report. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(12):1665–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2433-7.

Medina CA, Candiotti K, Takacs P. Wide genital hiatus is a risk factor for recurrence following anterior vaginal repair. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101(2):184–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.11.008.

Vaughan MH, Siddiqui NY, Newcomb LK, Weidner AC, Kawasaki A, Visco AG, et al. Surgical alteration of genital hiatus size and anatomic failure after vaginal vault suspension. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):1137–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002593.

Vakili B, Zheng YT, Loesch H, Echols KT, Franco N, Chesson RR. Levator contraction strength and genital hiatus as risk factors for recurrent pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1592–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.022.

Swenson CW, Masteling M, DeLancey JO, Nandikanti L, Schmidt P, Chen L. Aging effects on pelvic floor support: a pilot study comparing young versus older nulliparous women. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(3):535–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04063-z.

English EM, Chen L, Sammarco AG, Kolenic GE, Cheng W, Ashton-Miller JA, et al. Mechanisms of hiatus failure in prolapse: a multifaceted evaluation. Int Urogynecol J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04651-4.

Andrew BP, Shek KL, Chantarasorn V, Dietz HP. Enlargement of the levator hiatus in female pelvic organ prolapse: cause or effect? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53(1):74–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12026.

Wong V, Shek KL, Korda A, Benness C, Pardey J, Dietz HP. A pilot study on surgical reduction of the levator hiatus-the puborectalis sling. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(12):2127–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04062-0.

Muñiz KS, Voegtline K, Olson S, Handa V. The role of the genital hiatus and prolapse symptom bother. Int Urogynecol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04569-x.

Siff LN, Barber MD, Zyczynski HM, Rardin CR, Jakus-Waldman S, Rahn DD, et al. Immediate postoperative pelvic organ prolapse quantification measures and 2-year risk of prolapse recurrence. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(4):792–801. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004043.

Hill AM, Shatkin-Margolis A, Smith BC, Pauls RN. Associating genital hiatus size with long-term outcomes after apical suspension. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(8):1537–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04138-x.

Funding

Investigator support was provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant # R01 HD094954, R03 HD096189 and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) WRHR Career Development Award #K12 HD065257. The NIH and NICHD played no role in the research design, data collection/analysis, decision to publish, or choice of journal for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

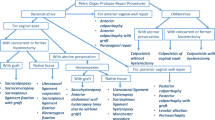

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Schmidt, P., DeLancey, J.O. et al. Analysis of long-term structural failure after native tissue prolapse surgery: a 3D stress MRI-based study. Int Urogynecol J 33, 2761–2772 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04925-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04925-5