Abstract

Several vaginal procedures are available for treating uterine descent. Vaginal hysterectomy is usually the surgeon’s first choice. In this literature review, complications, anatomical and symptomatic outcomes, and quality of life after vaginal hysterectomy, sacrospinous hysteropexy, the Manchester procedure, and posterior intravaginal slingplasty are described. All procedures had low complication rates, except posterior intravaginal slingplasty, with a tape erosion rate of 0–21%. Minimal anatomical success rates regarding apical support ranged from 85% and 93% in favor of the Manchester procedure. Data on symptomatic cure and quality of life are scarce. In studies comparing vaginal hysterectomy with sacrospinous hysteropexy or the Manchester procedure, vaginal hysterectomy had higher morbidity. Because no randomized, controlled trials have been performed comparing these surgical techniques, we can not conclude that one of the procedures prevails. However, one can conclude from the literature that vaginal hysterectomy is not the logical first choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is a common problem among aging women. About 50% of parous women have pelvic organ prolapse [1]. The lifetime risk at the age of 80 for surgical intervention is 11.1% [2]. Removal of the prolapsed uterus, eventually combined with preventive procedures for future vault prolapse, is considered the primary procedure in cases of uterine descent [3]. With a vaginal approach, combined vaginal repair methods, such as anterior or posterior colporrhaphy, are easy to perform. If one chooses a vaginal procedure to correct uterine descent, one can choose to retain and suspend the prolapsed uterus rather than removing it. Women have several reasons for wanting to preserve the uterus, such as retaining fertility and maintaining their personal identity. Other possible motivations may be the possibility that this kind of surgery might reduce operation time, blood loss, and postoperative recovery time [4, 5]. The choice of operation for uterine prolapse depends on the preference of the woman and her surgeon, eg, the surgeon’s expertise in different surgical techniques. The objective of this review is to outline the complication rate, anatomical success rate, functional outcomes, quality of life, and sexual function in women with uterine prolapse after a vaginal hysterectomy and three uterus-preserving vaginal techniques: sacrospinous hysteropexy, the Manchester procedure, and posterior intravaginal slingplasty.

Material and methods

Sources and search methods

After performing a MEDLINE search in November 2007 on vaginal surgical techniques for uterine descent, we selected four surgical procedures: vaginal hysterectomy (with or without prophylactic procedures for future vaginal vault prolapse) and three uterus-preserving procedures: sacrospinous hysteropexy, the Manchester procedure, and posterior intravaginal slingplasty. For each technique, a separate literature search was performed. The sacrospinous hysteropexy and posterior intravaginal slingplasty are relatively “young” procedures (first publication in 1989 and 2006, respectively). Therefore, to make the groups of women who underwent the different procedures somewhat more comparable, we chose to only use data published over the last 20 years. The MEDLINE search was performed with the key words and phrases “English,” “Human,” “Female,” “all adults 19 years old and above,” and “reports published between 1 November 1987–1 November 2007,” and had the following results:

-

1.

Prolapse and vaginal hysterectomy (176 reports)

-

2.

Prolapse and sacrospinous hysteropexy or sacrospinous ligament fixation or sacrospinous colpopexy (71 reports)

-

3.

Prolapse and Manchester or Fothergill or cervical amputation (90 reports)

-

4.

Prolapse and intravaginal slingplasty or posterior intravaginal slingplasty or intravaginal sling or infracoccygeal sacropexy (32 reports)

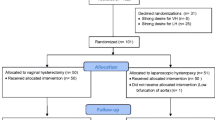

Also the following databases were searched: EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Current Controlled Trials, and the Database of Abstracts on Reviews and Effectiveness. First, we searched for randomized trials. One randomized trial was found comparing vaginal hysterectomy with an abdominal procedure and one randomized trial was found comparing vaginal hysterectomy with sacrospinous hysteropexy [6, 7]. After that, prospective cohort studies, prospective, case-controlled studies, retrospective studies, and case reports were assessed. Finally, we included different types of clinical research because in most cases no or little (randomized) data were available.

Study selection

Titles and, if available, abstracts of all literature found after this search were assessed. The full report of each study likely to be relevant was then assessed, including the reference lists.

The vaginal hysterectomy search found 176 reports. However, most of these reports focused on outcome after vaginal hysterectomy (in most cases in comparison with abdominal hysterectomy) for benign diseases in general, not for the indication of prolapse separately. It is important to focus on this subgroup separately, because data on complications and outcome with regard to symptoms and anatomical recurrences will be different compared with complications and outcomes in a subgroup of women who underwent vaginal hysterectomy for other benign diseases like menorrhagia or leiomyoma. This is reflected in data published by Dallenbach et al. in which the risk of prolapse repair after hysterectomy was 4.7 times higher in women whose initial hysterectomy was indicated for prolapse and 8.0 times higher if preoperative prolapse grade 2 or more was present [8]. When selecting only reports on women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse, we found 38 eligible reports. However, many of these studies describe a prophylactic method for future vaginal vault prolapse in women without a uterus and in women in whom the uterus had to be removed at the time of this prophylactic procedure. In many reports, outcomes in these subgroups of women (in which a vaginal hysterectomy was performed) were not separately described. Therefore, 15 studies were excluded. Twenty-three studies were available in which outcome data for 1,764 women who underwent a vaginal hysterectomy for prolapse symptoms were analyzed separately, with a follow-up of between 9 and 60 months [4, 5, 6, 9–28].

The sacrospinous hysteropexy search resulted in 71 reports. After selection and assessment of reference lists, 11 studies and one case report were found on women who underwent a sacrospinous hysteropexy (with preservation of the uterus) [4, 5, 7, 16, 17, 21, 29–33]. A total of 613 women who underwent a unilateral sacrospinous hysteropexy are described, with a follow-up of between 4 and 72 months. One study by Kovac and Cruikshank reports on four women with a unilateral sacrospinous hysteropexy and 15 women with a bilateral sacrospinous hysteropexy. Because of the bilateral approach, in contrast to the unilateral approach in all other studies, data on anatomical outcome and complication rate were not used in this review [32].

The Manchester procedure search found 90 reports. After assessment of these reports including reference lists of eligible studies, four studies and two case reports were found with data on 573 women [18–20, 34–36]. All studies were retrospective. Follow-up varied from 12 to 43 months.

After assessment of the 32 reports and their reference lists, only four studies describing posterior intravaginal slingplasty in women preserving their uterus were available [37–40]. Because Mattox et al. did not describe their subgroup of only two women with preservation of the uterus separately (21 women without a uterus), this report was excluded from the analyses of anatomical and functional outcomes [40]. A total of 143 women were analyzed with a follow-up of 6 to 30 months. In none of the studies were complications separately described for the subgroup of women in which the uterus was preserved. Therefore, for describing complications, we used data for women who underwent a posterior intravaginal slingplasty with and without preservation of the uterus [37–47].

Measurements

The following outcome measurements were reviewed: complications, anatomical outcomes, symptomatic outcomes, quality of life, sexual function, and pregnancy after the three uterus-preserving techniques.

Surgical procedures

Vaginal hysterectomy was first performed by Langenbeck in 1813 [48]. The vaginal hysterectomy surgical technique is well described in surgical textbooks [49]. After removing the uterus, prophylactic procedures to prevent future vaginal vault prolapse, such as sacrospinous ligament fixation [4, 16] or McCall culdoplasty [50], can be performed.

The sacrospinous hysteropexy was first described by Richardson in 1989 [29]. After opening the posterior vaginal wall, the right sacrospinous ligament is made visible through sharp, blunt dissection into the right para rectal space. The cervix is unilaterally attached to the right sacrospinous ligament, about 2 cm medial from the ischial spine with two nonabsorbable sutures.

In 1888, Archibald Donald of Manchester started treating women with uterovaginal prolapse with the combined operation of anterior and posterior colporrhaphy and amputation of the cervix, the Manchester procedure [51]. Edward Fothergill modified the procedure by including parametrial fixation [52]. The procedure consisted of the following elements: an anterior colporrhaphy including wide exposure of the parametria, suturing of the parametrial tissues in front of the cervix and lower uterine segment thereby shortening the ligaments and elevating the cervix, amputation of the cervix if necessary, and a posterior colpoperineorrhaphy.

In 2001, the posterior intravaginal slingplasty was introduced by Petros [41]. It was a minimally invasive, transperineal technique providing Level I support, as described by DeLancey, by making neo-sacrouterine ligaments using mesh [53]. Different materials have been used because the first nylon mesh had high rates of erosions. Later, polypropylene multifilament mesh was introduced.

In all reports of these four surgical techniques, concomitant surgery (anterior or posterior colporrhaphy or vaginal incontinence surgery) was performed when indicated.

Results

Complications

Table 1 shows the occurrence of complications. The vaginal hysterectomy complication rates reported in these studies are comparable to complication rates in large retrospective studies of vaginal hysterectomy for benign disease in general. The mortality rate varies between 0.04% and 0.1% [54, 55]. No deaths were reported in the selected studies of this review. Vaginal hysterectomy was compared with the Manchester procedure in two studies in which hysterectomy was associated with a significantly longer operating time and greater morbidity (blood loss, vaginal cuff abscesses) [19, 20]. When comparing vaginal hysterectomy (in two studies combined with a prophylactic sacrospinous ligament fixation) with sacrospinous hysteropexy, the associated morbidity (longer operating time and recovery time and more blood loss) of a vaginal hysterectomy was greater as compared to the sacrospinous hysteropexy [4, 5, 16]. After sacrospinous hysteropexy in two women (in one retrospective study), persistent buttock pain with the need for a second surgery occurred [33]. In one woman, the suture was removed and replaced 1 day after surgery and she completely recovered. In the other woman, it was unclear whether the pain was caused by the sacrospinous hysteropexy or related to neurological problems in the lumbar region. After 3 years, the suture was removed and the patient underwent a vaginal hysterectomy after which her pain decreased but did not resolve. In all other women, the buttock pain resolved within 6 weeks without any intervention. One study reports that the Manchester procedure was associated with hematometra due to cervical stenosis with the need for cervical dilatations in up to 11% of patients [34]. In one woman, after four dilatations of the cervix, an abdominal hysterectomy was performed. Hopkins et al. reported on three patients with uterine disease (two with cancer) after a Manchester procedure in women who thought that their uterus had been removed in prior prolapse surgery, which made the differential diagnosis difficult [35]. Therefore, after cervical amputation, a risk of stenosis is present, which could influence the occurrence of alarming symptoms (vaginal blood loss) in the development of adenocarcinoma of the uterus. After a posterior intravaginal slingplasty (with and without preservation of the uterus) mesh erosion problems were reported in 0% to 21% of women [37–47]. Baessler et al. described erosion problems in 13 women who were referred to their clinic after implantation of a multifilament mesh at other clinics [56]. Mesh infection, pain syndromes, and dyspareunia after a median time of 24 months were the main indications for removing the mesh. Follow-up after mesh removal showed that symptoms in all women disappeared or decreased. Several explanations for the different prevalence rates of IVS mesh erosion were given. Atachi et al. report that women operated on by less-experienced surgeons had more erosion problems than women who were operated on by more experienced surgeons [57]. Hefni et al. did not confirm these findings but reported that older age (>60 years) and diabetes mellitus were associated with a higher rate of mesh erosions [39]. Also the nature of the tape might play an important role. Farnsworth first had an erosion rate of 10% with nylon tape; after he started using polypropylene mesh, the erosion rate dropped to 0% [47]. However, as with the majority of studies reported in this review, well-designed studies with clear outcomes (both anatomical and functional) on the IVS posterior procedure have to be awaited. Removal of the uterus during the procedure did not alter the erosion rate but it did increase the hospital admission time (1.5 versus 4.2 days, P = 0.002) [37].

No randomized trials were available comparing the surgical procedures with regard to complications. In comparative studies, vaginal hysterectomy was associated with greater morbidity compared with sacrospinous hysteropexy (aside from a short period of buttock pain) and also when it is compared to the Manchester procedure (aside from cervical stenosis). All procedures were associated with a low complication rate.

Anatomical cure

In this part of the analyses we focus only on the anatomical outcome of the apical compartment. The heterogeneity of the studies involved, with respect to other surgical procedures performed in addition to the apical fixation, makes it virtually impossible to compare the techniques on their outcome on the anterior or posterior compartment.

The anatomical outcome with respect to fixation of the apical compartment is comparable for all techniques with success rates over 85% (Table 2). Surgery for recurrent apical prolapse symptoms ranged from 0% to 7% (Table 2). Two studies reported on the comparison of the sacrospinous hysteropexy (one prospectively and one retrospectively) with a vaginal hysterectomy with prophylactic sacrospinous ligament fixation of the vaginal vault [4, 16]. In these studies, anatomical cure (also symptomatic cure and satisfaction) was comparable between groups. The authors concluded that hysterectomy had no favorable effect. Apical cure after the Manchester procedure was excellent and varied between 93–100%. However, all studies included were of a retrospective design with data collected from medical charts or by sending questionnaires to women or surgeons.

Anatomical outcome data after posterior intravaginal slingplasty with preservation of the uterus were collected prospectively with follow-up between 6 and 30 months on143 women in three studies.

It is important to note that all studies reviewed were heterogenic with respect to follow-up time, selection of study group (eg, no stage 4 prolapse included, prior prolapse surgery, and additional surgery), definition of recurrent prolapse, and in methods of data collection. This limits the strengths of our finding considerably and emphasizes the need for well-designed randomized controlled trials in this area.

Symptomatic cure and quality of life

Probably more important than anatomical cure is the functional outcome of prolapse surgery. An illustration that symptoms are not always associated with anatomical outcome is the recent study on the sacrospinous hysteropexy by Dietz et al. in which women with and without a cystocele stage 2 or more described the same amount of bother on urogynecological symptoms [33]. For measuring these functional outcomes the use of validated disease-specific symptom and quality of life questionnaires is highly recommended [58].

Because hysterectomy can disrupt the local nerve supply and will affect the anatomical relationships of the pelvic organs, it has been thought that the functions of these organs may be adversely affected after surgery. However, to investigate these functions, validated questionnaires are useful. Roovers et al. used validated questionnaires on urogenital symptoms and quality of life [27]. They found improvement in all urogenital domain scores (urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, pain, prolapse, and obstructive micturition) and quality of life (mobility, physical function, social functioning, emotional functioning, and embarrassment) after a vaginal hysterectomy. We have to acknowledge that prolapse itself can cause urogenital symptoms, so these symptoms may disappear after prolapse surgery. It has been debated for many years that a vaginal hysterectomy possibly contributes to the development of urinary symptoms. In a prospective study, in which a vaginal hysterectomy was compared with endometrial ablation for the treatment of menorrhagia (not for prolapse symptoms), no differences in incontinence rates were found between the groups [59]. In a review of the literature, it was concluded that a vaginal hysterectomy is unlikely to cause bladder and bowel dysfunction [60]. The occurrence of de novo stress incontinence after a vaginal hysterectomy for uterine descent was reported in between 0% and 22% of women [6, 14, 17, 23, 24].

No reports were found of women developing de novo stress incontinence after sacrospinous hysteropexy, but recurrent stress incontinence occurred in up to 4% [4]. With the use of a validated questionnaire in a retrospective study design, symptoms of an overactive bladder appeared to be more prevalent after a vaginal hysterectomy as compared to a sacrospinous hysteropexy (48% vs. 39%) [5]. Prospective data on changes in quality of life, as measured with validated questionnaires, were not available.

No studies on the Manchester procedure report the use of validated symptom and quality of questionnaires. No data on de novo stress incontinence were found. In the study by Dutta et al., a reduction of stress incontinence symptoms from 6% to 1% after surgery is described [18].

Neuman et al. found “satisfaction with the posterior intravaginal slingplasty with preservation of the uterus” in 91.4% of women [37]. The prevalence of overactive bladder symptoms reduced from 71% to 10% postoperatively. Again, the lack of use of validated questionnaires in studies on the IVS makes the interpretation and comparison of data difficult.

In conclusion there is limited evidence on the functional outcome of the different techniques with respect to urogenital symptoms. Recommendations on one technique or the other from a functional point of view cannot be made.

Sexual functioning

Sexual well-being may decrease after hysterectomy due to damage of the innervations and supportive structures of the pelvic floor, but may also improve due to the resolution of prolapse symptoms. Many studies have been published about sexual function after a hysterectomy for benign conditions and they have shown that a simple vaginal hysterectomy is not a risk factor for sexual dysfunction [60]. After surgery for uterine prolapse (including vaginal hysterectomy), sexuality improved or did not change in most women [61]. If a large cystocele was present before surgery and corrected during surgery this was associated with the disappearance of sexual problems after surgery. Mild to severe dyspareunia symptoms are reported in up to 14% of women after a vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse [25]. After a sacrospinous hysteropexy, dyspareunia was reported in 0% to 7% of women [4, 16]. In a randomized study comparing women after a sacrospinous hysteropexy and a vaginal hysterectomy, no difference was reported in postoperative sexual functioning at 6-month follow-up [7]. A decrease in the frequency of orgasm was reported after both procedures. This was reported to be related to the fact that these women were afraid of wound disruption or disease recurrence. Pain during intercourse before and after surgery was equal in both groups (4% before surgery, 5% after surgery).

No information on sexual function in women after a posterior intravaginal slingplasty was reported except for dyspareunia complaints that did not occurred when the uterus was preserved during the procedure [37]. After a posterior intravaginal slingplasty in women in which the uterus was removed, 5% of women reported dyspareunia symptoms after surgery [45].

In conclusion, although in retrospective studies the vaginal hysterectomy is associated with the highest dyspareunia rate, the only randomized study comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy and vaginal hysterectomy showed that the two procedures did not differ at 6-month follow-up.

Pregnancy

Tipton et al. describe five women (total study group of 82 women) who desired pregnancy after the Manchester procedure [62]. Two of them had an uneventful pregnancy, one had a miscarriage at 3 months and two had no pregnancy at all. There was no follow-up on these women. Also three unplanned pregnancies occurred in the total study group. The risk of premature delivery is unknown after the Manchester procedure but is possibly higher when cervical amputation is performed.

Pregnancy after a sacrospinous hysteropexy is described in 14 women (a total of 15 pregnancies, one of which was a twin pregnancy) [4, 30–32]. Six of these pregnancies ended with a vaginal delivery and nine with a caesarean. After vaginal delivery, one woman needed a second prolapse surgery (this patient delivered twice). After caesarean delivery, one woman also needed a second prolapse surgery.

No data are available on pregnancies after a posterior intravaginal slingplasty.

Discussion

All three uterus-preserving procedures appear to be equally effective with regard to anatomical apical cure and recurrent prolapse surgery, with less morbidity (operating time, blood loss, and recovery time) for the three uterus preserving techniques, compared with vaginal hysterectomy. However, vaginal hysterectomy, combined with prophylactic methods for the vaginal vault, is still the first choice procedure in many countries. Most likely, the morbidity associated with vaginal hysterectomy, as described in Table 1, is considered mild (or is unknown) by doctors and patients. In addition, women may want to have their uterus removed because of fear of bleeding disorders or cancer of the cervix or uterus in future times. Both the IVS-posterior as well as the sacrospinous ligament fixation can be performed with or without a hysterectomy. From the studies we evaluated, it appears that that removing the uterus during these procedures is not beneficial [4, 17, 37].

Length of hospital stay was not described in most studies. However, the IVS posterior was associated with a very short hospital stay (1.5 days) [37]. We have to keep in mind that the length of hospital stay is related to many factors such as age, preoperative morbidity, organization of health care, distance to hospitals, and opinion of the doctor.

The studies available were difficult to compare because of the major differences in data collection (retrospective, prospective) and definition of recurrences. We have to be aware that examining all women after surgery at longer follow-up most likely will show higher recurrence rates compared to recurrence rates reported in the medical records for the following reasons: first, some women with recurrent symptoms could have gone to another clinic for a second surgery. Second, some women with recurrent symptoms could have not wanted a second surgery and therefore did not return to the clinic. Third, some women could have been treated with a pessary by their general practitioner. Fourth, many women with an anatomical recurrence on gynecological examination will be asymptomatic and therefore these women may not have returned to the clinic. Finally, symptoms may develop beyond the time frame of the study and are therefore not reported.

One severe limitation of our review is the fact that there is a marked heterogeneity between the way studies are designed and performed. For example differences in follow-up time, baseline characteristics of the research groups (differences in age, preoperative stage of prolapse, or previous prolapse surgery), definition of recurrences and even differences in surgical technique within the groups themselves makes it difficult to pool data from all the studies. Also, we have to acknowledge that there may be a publication bias that could have influenced these results.

Because no randomized, controlled trials are available for the four surgical techniques (except for one trial containing data on sexual functioning), we can not state that one procedure is better than another [7]. Hopefully, this report will motivate researchers to perform such a trial.

In conclusion, we can state that, with the information from the current literature, it is not necessary that women will undergo vaginal hysterectomy for uterine descent. In comparative studies, sacrospinous hysteropexy and the Manchester procedure were, with regard to anatomical outcome, equally effective with less severe morbidity compared with that of vaginal hysterectomy for uterine descent. The IVS posterior showed good results but carries the risk of mesh erosion. Perhaps a monofilament polypropylene mesh, which was shown to be superior to the multifilament mesh in urinary incontinence surgery with regard to erosion rates, will reduce the risk of erosion in posterior intravaginal slingplasty [63] although Sivaslioglu et al. recently showed that these erosions might be technique related [64].

References

Slieker-ten Hove MCP, Vierhout M, Bloembergen H, Schoemaker G (2004) Distribution of POP in the general population; prevalence, severity, etiology and relation with the function of the pelvic floor muscles. ICS Paris

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL (1997) Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89(4):501–506

Swati JHA, Moran PA (2007) National survey of prolapse in the UK. Neurol Urodyn 26:325–331

Maher CF, Cary MP, Slack CJ, Murray CJ, Milligan M, Schluter P (2001) Uterine preservation or hysterectomy at sacrospinous colpopexy for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 12:381–385

Brummen HJ, van de Pol G, Aalders CIM, Heintz APM, van der Vaart CH (2003) Sacrospinous hysteropexy compared to vaginal hysterectomy as primary surgical treatment for a descensus uteri: effects on urinary symptoms. Int Urogynecol J 14:350–355

Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, van Leeuwen JH, Scholten PC, Heintz AP (2005) A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn 24(4):334–340

Jeng CJ, Yang YC, Tzeng CR, Shen J, Wang LR (2005) Sexual functioning after vaginal hysterectomy or transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension for uterine prolapse. J Reprod Med 50:669–674

Dällenbach P, Kaelin-Gambirasio I, Dubuisson JB, Boulvain M (2007) Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse repair after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 110:625–32

Marchionni M, Bracco GL, Checcucci V, Carabaneanu A, Coccia EM, Mecacci F, Scarselli G (1999) True incidence of vaginal vault prolapse. J Repr Med 44:679–684

Cruikshank SH (1990) Sacrospinous ligament fixation at the time of transvaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 162:1611–1615

Hofmann MS, Harris MS, Bouis PJ (1996) Sacrospinous colpopexy in the management of uterovaginal prolapse. J Repr Med 41:299–303

Borenstein R, Elchalal U, Goldchmit R, Rosenman D, Ben-Hur H, Katz Z (1992) The importance of the endopelvic fascia repair during vaginal hysterectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 175:551–554

Porges RF, Smilen SW (1994) Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171:1518–1528

Marana HRC, Andrade JM, Fonzar Marana RRN, de Sala MM, Philbert PMP, Rodrigues R (1999) Vaginal hysterectomy for correcting genital prolapse. J Repr Med 44:529–534

Guner JH, Novan V, Tiras MB, Yildiz A, Yildirim M (2001) Transvaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for marked uterovaginal and vault prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 74:165–70

Hefni MA, El-Toukhy TA (2006) Long-term outcome of vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for marked uterovaginal and vault prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 127(2):257–263

Hefni M, El-Toukhy T, Bhaumik J, Katsimanis E (2003) Sacrospinous cervicocolpopexy with uterine conservation for uterovaginal prolapse in elderly women: an evolving concept. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188(3):645–650

Dutta DK, Dutta B (1994) Surgical management of genital prolapse in an industrial hospital. J Indian Med Assoc 92:366–377

Kalogirou D, Karakitsos AG, Kalogirou O (1996) Comparison of surgical and postoperative complications of vaginal hysterectomy and Manchester procedure. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 17:278–280

Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, Bodian C, Friedman F Jr, Bogursky E (1995) Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med 40:299–304

Carey MP, Slack MC (1994) Transvaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vault and marked uterovaginal prolapse. Br J Obstet Gynecol 101:536–540

Tanaka S, Yamamoto H, Shimano S, Endoh T, Hashimoto M (1988) A vaginal approach to the treatment of genital prolapse. Asia-Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol 14:161–165

Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, Weld A, Rosenblatt P, Kohli N (2005) Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 17:79–83

Koyama M, Yoshida S, Koyama S, Ogita K, Kimura T, Shimoya K, Murata Y, Nagata I (2005) Surgical reinforcement of support for the vagina in pelvic organ prolapse: concurrent iliococcygeus fascia colpopexy (Inmon technique). Int Urogynecol J 16:197–202

Colombo M, Milani R (1998) Sacrospinous ligament fixation and modified McCall culdoplasty during vaginal hysterectomy for advanced uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179:13–20

Montella JM, Morril MY (2005) Effectiveness of the McCall culdoplasty in maintaining support after vaginal hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J 16:226–229

Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, van Leeuwen JH, Scholten PC, Heintz AP (2004) A randomized controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG 111:50–56

Ahn KY, Hong JS, Kim NY, Lee HJ, Choi NM, Han HS, Sung SJ, Kim JM, Joo KY, Choi KH (2006) Hysterectomy; is it essential for the correction of uterine prolapse? Korean J Obstet Gynecol 49:1313–1319

Richardson DA, Scotti RJ, Ostergard DR (1989) Surgical management of uterine prolapse in young women. J Reprod Med 34(6):388–392

Hefni M, El-Thoukhy T (2002) Sacrospinous cervico-colpopexy with follow-up 2 years after successful pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol 103:188–190

Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, Lee MY, Hsieh CH, Wang KG, Chen GD (2005) Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc 4:249–253

Kovac SR, Cruikshank SH (1993) Successful pregnancies and vaginal deliveries after sacrospinous uterosacral fixation in five of nineteen patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 168:1778–1786

Dietz V, de Jong J, Huisman M, Schraffordt Koops S, Heintz P, van der Vaart H (2007) The effectiveness of the sacrospinous hysteropexy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 18:1271–1276

Ayhan A, Esin S, Guven S, Salman C, Ozyuncu O (2006) The Manchester operation for uterine prolapse. Int J Gynecol Obstet 92:228–233

Hopkins MP, Devine JB, DeLancey JO (1997) Uterine problems discovered after presumed hysterectomy: the Manchester operation revisited. Obstet Gynecol 89:846–848

Skiadas CC, Goldstein DP, Laufer MR (2006) The Manchester-Fothergill procedure as a fertility sparing alternative for pelvic organ prolapse in young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 19:89–93

Neuman M, Lavy Y (2007) Conservation of the prolapsed uterus is a valid option: medium term results of a prospective comparative study with the posterior intravaginal slingplasty operation. Int Urogynecol J 18:889–893

Vardy MD, Brodman M, Olivera CK, Zhou HS, Flisser AJ, Bercik RS (2007) Anterior intravaginal slingplasty tunneler device for stress incontinence and posterior intravaginal slingplasty for apical vault prolapse: a 2-year prospective multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 104:e1–e8

Hefni M, Yousri N, El-Thoukhy T, Koutromanis P, Mossa M, Davies A (2007) Morbidity associated with posterior intravaginal slingplasty for uterovaginal and vault prolapse. Arch Gynecol Obstet 276:499–504

Mattox TF, Moore S, Stanford EJ, Mills BB (2006) Posterior vaginal sling experience in elderly patients yields poor results. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194:1462–1466

Papa Petros PE (2001) Vault prolapse II: restoration of dynamic vaginal supports by infracoccygeal sacropexy, an axial day-case vaginal procedure. Int Urogynecol J 12:296–303

Sivaslioglu AA, Gelisen O, Dolen I, Dede H, Dilbaz S, Haberal A (2005) Posterior sling (infracoccygeal sacropexy): an alternative procedure for vaginal vault prolapse. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 45:159–160

Foote AJ, Ralph J (2007) Infracoccygeal sacropexy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 47:250–251

Ghanbari Z, Baratali BH, Mireshghi MS (2006) Posterior intravaginal slingplasty (infracoccygeal sacropexy) in the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse. Int J Gynecol Obstet 94:147–148

Jordaan DJ, Prollius A, Cronjé HS, Nel M (2006) Posterior intravaginal slingplasty for vaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 17:326–329

Biertho I, Dallemagne B, Dewandre JM, Markiewicz S, Monami B, Wahlen C, Weerts J, Jehaes C (2005) Intravaginal slingplasty: short term results. Acta Chir Belg 104:700–704

Farnsworth BN (2002) Posterior intravaginal slingplasty (infracoccygeal sacropexy) for severe posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse—a preliminary report on efficacy and safety. Int Urogynecol J 13:4–8

Langenbeck JCM (1819-1820) Geschichte einer von mir glucklich verrichteten Estirpation der ganzen Gebarmutter. N Biblioth Chir Ophthalmol 1:551

Hirsch HA, Kaser O, Iklé FA. Vaginal hysterectomy (1997) Atlas of gynecologic surgery. Thieme, Stuttgard-New York, pp 226–238

McCall ML (1957) Posterior culdeplasty: surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy; a preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol 10(6):595–602

Donald A (1921) A short history of the operation of colporrhaphy, with remarks on the technique. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 28:256–259

Fothergill WE (1913) Clinical demonstration of an operation for prolapse uteri complicated by hypertrophy of the cervix. BMJ 1:762–765

DeLancey JO (1993) Anatomy and biomechanics of genital prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol 36:897–909

Sheth SS (2004) The scope of vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol 115:224–230

Mathevet P, Valencia P, Cousin C, Melilier G, Dargent D (2001) Operative injuries during vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol 97:71–75

Baessler K, Maher C (2006) Severe mesh complications following intravaginal slingplasty. Obstet Gynecol 107:422–423

Achtari C, Hiscock R, O’Reilly BA, Schielitz L, Dwyer PL (2005) Risk factors for mesh erosion after transvaginal surgery using polypropylene (Atrium) or composite polypropylene/polyglactin 910 (Vypro II) mesh. Int Urogynecol J 16:389–394

Maher C, Baessler K, Glazener CMA, Adams EJ, Hagen S (2007) Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 3 Art. No.: CD004014. doi:10.1002/14651858

De Tayrac R, Chevalier N, Chauveaud-Lambling A, Gervaise A, Fernandez H (2004) Risk of urge and stress urinary incontinence at long-term follow-up after vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:90–94

Thakar R, Sultan AH (2005) Hysterectomy and pelvic organ dysfunction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 19:403–418

Roovers JP (2001) Effects of genital prolapse surgery and hysterectomy on pelvic floor function. Manuscript

Tipton R, Atkin P (1970) Uterine disease after the Manchester repair operation. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 77:852–853

Baghfi A, Valerio L, Benizi EI, Trastour C, Benizri EJ, Bongain A (2005) Comparison between monofilament and multifilament polypropylene tapes in urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 122:232–236

Sivaslioglu AA, Unlubilgin E, Dölen I (2008) The multifilament polypropylene tape erosion trouble: tape structure vs surgical technique. Which one is the cause? Int Urolgynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 19(3):417–420

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. dr. A.P.M. Heintz and Prof. dr. Y. van der Graaf for reading this review critically.

Conflicts of interest

None

Funding

None

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0867-0

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dietz, V., Koops, S.E.S. & van der Vaart, C.H. Vaginal surgery for uterine descent; which options do we have? A review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J 20, 349–356 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0779-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0779-4