Abstract

The objective of this paper is to explain the reasons behind the dynamics of labor productivity (LP) growth during a process of institutional and structural change. We show - by means of a theoretical discussion and an empirical analysis, conducted on a sample of 25 European countries for the period 1995–2016 - that four main channels contribute to explaining the evolution of LP. First, the speed of investment, which incorporates innovation and favors an increase of LP growth; second, the speed of Research and Development (R&D), which allows for the creation of new ideas and shows the “dynamism of a society”, having positive effects on LP; third, the deregulation of labor markets and the increase of temporary employment, both of which encourage labor-intensive strategies by firms, with low value-added and low productivity gains; fourth, the direction of structural change, which can take place toward services industries affected by “Baumol’s disease”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, several developed countries have experienced a productivity slowdown, which has taken place in the middle of a process of institutional and structural change.

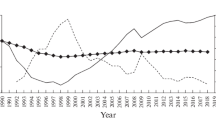

As shown in Fig. 1, a common trend seems to emerge. Independently of the socio-economic welfare model,Footnote 1 labor productivity growth in the European countriesFootnote 2 in the four panels has displayed a decreasing or stagnating pattern.Footnote 3

Rate of growth of labor productivity (moving average over three years), selected countries. (See Figure 2 in the appendix for some descriptive evidence on non-European countries, which substantiate the claim of a worldwide productivity slowdown.) Source: own elaboration on Eurostat data

The main purpose of this article is to provide a theoretical and empirical analysis of the impact of some major socio-economic phenomena on the dynamics of labor productivity. We aim to show both theoretically and by means of an econometric model applied to EU countries that four main channels contribute to explaining the evolution of our variable of interest. First would be the speed of investment (measured by the rate of investment growth), which incorporates innovation and favors an expansion of aggregate demand and an increase of LP (in the sense of Kaldor and Schumpeter). We will discuss the role of institutionsFootnote 4 in fostering innovation; in this sense we build a bridge between Schumpeterian and Kaldorian insights. More specifically, Kaldor’s ideas – and in particular his technical progress function – are recalled, to stress the importance of investment in physical assets as a vector of technological advancement. However, the productivity stagnation commenced, in different countries, a few years earlier than the slowdown in capital accumulation. Hence, the latter cannot be the causa causans of the former, but more a reinforcing factor for an already underway process. For this reason, we look for other co-determinants of the phenomenon we are trying to explain. The second channel is the speed of investment in Research and Development (R&D), which allows for the creation of new ideas and shows the “dynamism of a society” in the sense of Kaldor, with positive effects on LP. The third channel is the deregulation of the labor market and the increase of temporary employment, along with stagnant wages, all of which encourage labor-intensive strategies by firms, with low value-added and low productivity gains, following the Sylos Labini approach. The fourth channel is the direction of structural change. If this takes place in services industries experiencing Baumol’s disease, which suffer from specific obstacles to innovation and tend to be intensive in unskilled labor, there is little room for productivity gains and labor productivity is likely to slow down. Therefore, we argue, structural change needs to be governed and channeled with proper incentives both in the labor market and in the investment sector. Policies and institutions are crucial for this objective. Innovation and technical progress take place within an institutional framework able to create the proper incentives for agents to invest, risk and interact. This framework also needs to adapt to the new technological systems that have meanwhile emerged.

Over the last three to four decades, many advanced economies have experienced significant changes in their productive structures and their industrial strategies.Footnote 5 While the post-WWII period of expansion – qualified by some scholars as “The Golden Age of Capitalism” (Marglin and Schor 1990) – was characterized by the manufacturing industry exerting the leading role, in more recent years a massive shift in employment has been taking place in most Western countries. Indeed, a steady decline in the share of workers employed in manufacturing and a transition towards the service sector is a well-known feature of contemporary capitalism.Footnote 6 Additionally, as highlighted, for example, in Szirmai (2012) and Rodrik (2016), such deindustrializationFootnote 7 trends are similarly observable in developing countries, with a relative exception being presented by Asian industrial exporters.

In the remainder of this article, we will try to explore channels that operate through both the demand and the supply side of the economy, with a special focus being placed on labor market flexibilization and transformations in the productive structure of the economies involved. In Sections 2–4, we will conduct a selected review of the literature to try to uncover possible explanations for the slowdown of productivity growth that is being experienced by most European countries. The paper proceeds as follows: in Section 2 we explore the possible threats to the dynamics of labor productivity that can arise from an ungoverned process of structural change. To do this, we draw first on the classic works of Baumol and Kaldor, which are then enriched with more recent contributions that outline the heterogeneous nature of different service industries. Section 3 establishes a link between labor flexibility and productivity, claiming that a certain degree of rigidity in labor market institutions can be beneficial as it deters the adoption of labor-intensive strategies and pushes, through creative destruction, non-innovators out of the market. Section 4 discusses the role of institutions in fostering innovation and investment and tries to find the meeting point between Keynes, Schumpeter and Kaldor. In Section 5, we submit the main ideas of Sections 2–4 to empirical scrutiny by means of a panel data analysis conducted on a sample of 25 European countriesFootnote 8 for the period 1995–2016. The results are broadly consistent with our expectations. The last section concludes.

2 Structural change and labor productivity: A brief review

In this paper, we want to assess whether the process of structural change – briefly illustrated above – can contribute to explaining recent trends in labor productivity.Footnote 9 The literature has been debating this issue for decades and no consensus has emerged. On the one hand, it has been argued and found, for example in the influential empirical work of Hartwig (2011), that “structural change has a growth-dampening effect” (Hartwig 2011, p. 485) for both the US and a group of fifteen European countries. This idea is obviously not new and dates back at least to Baumol and Bowen (1965), Kaldor (1966) and Baumol (1967). It is easily summarized as follows: “a transfer of resources from manufacturing to services may provide a structural change burden” (Szirmai and Verspagen 2015, p. 47).

On the other hand, in more recent years the very idea of the existence of Baumol’s disease affecting the dynamics of aggregate labor productivity has been questioned and critically discussed.Footnote 10 In an influential contribution, for example, Triplett and Bosworth claim sic et simpliciter that “Baumol’s disease has been cured” (Triplett and Bosworth 2003, p. 23) and that the over-emphasis in previous years on such a disease might have been due to difficulties in correctly measuring productivity in services.Footnote 11

In our view, nonetheless, at least several certain service industries have a limited potential for productivity gains, being structurally defined by labor-intensive production processes. Moreover, as pointed out by Wölfl (2005), service industries might suffer from specific obstacles to innovation: for example, the average small size of firms in this sector (and the related difficulties in gathering the necessary financing) leads to low investment, specifically in high-risk, high-tech capital assets (Wölfl 2005, p. 55). Added to this, investments in R&D and in workforce training tend to be underfunded and industries operating in the service sector often resort to non-firm specific technologies and knowledge that has been developed elsewhere (ibid.). Finally, we find persuasive the arguments that have been collectively labeled as the “Manufacturing Imperative” (Rodrik 2011), discussed and summarized in Cirillo and Guarascio (2015). In this scenario, an advanced manufacturing sector generates innovation spillover into service industries; manufactured capital goods used by the service sector embody most of the technical progress and knowledge generated in the economy (see Kaldor’s discussion below). Moreover, being tradable, they are an efficient vector for disseminating innovation.

Maroto and Rubalcaba advance a more nuanced view. Indeed, they list “intensive utilization of the labor force, innovation barriers, low competition, the smaller size of enterprises or differences within labor market conditions” (2008, p. 349) as internal, structural characteristics of the service industries that can potentially slow down the pace of technological progress and innovation.Footnote 12 They also notice that, “to a certain extent” and at a very aggregate level, Baumol’s disease can still be considered valid; nonetheless, the picture across different service industries is uneven and sub-sectors such as transport, communication, finance and some business-related services contribute substantially to productivity growth.Footnote 13

3 Labor flexibility and productivity

One of the aims of this work is to assess the impact of the generalized flexibilization of labor relations on the dynamics of labor productivity.Footnote 14 There are several theoretical arguments put forward in the relevant literature that present a negative relationship between labor flexibility and productivity.Footnote 15 As argued by Storm and Naastepad, unstable labor relations may erode social capital and trust and induce firms to invest less readily in workers’ firm-specific human capital (Storm and Naastepad 2012, 2015). A similar line of reasoning can also be found in the perspective of the models of the New Keynesian Economics, which consider work effort – at the margin - to be positively correlated with wages; so, in that sense, unstable jobs, flexibility, scarce incentives and low-paid jobs push workers to put less effort into their work. Moreover, this type of employment leads to a lower likelihood that firms and workers will invest in training and education to improve the quality of human capital culminating in lower returns in terms of productivity, ceteris paribus, for the economic system (Salop 1979; Shapiro and Stiglitz 1984).

From a non-mainstream perspective, similar arguments can be found in the works of Vergeer and Kleinknecht. In Vergeer and Kleinknecht (2010), the authors perform a panel data analysis based on 19 OECD countries, for the period 1960–2004. Among their main results, flexible labor relations are found to damage labor productivity growth through multiple channelsFootnote 16 (p. 393) and to disincentivize knowledge accumulation. Interestingly, Vergeer and Kleinknecht provide evidence that the labor productivity slowdown is not only due to the creation of precarious, deregulated, and low-productivity jobs, but the productivity of existing jobs is negatively affected as well. Vergeer and Kleinknecht (2014) perform a similar exercise involving 20 OECD countries in the same time span (1960–2004) of Vergeer and Kleinknecht (2010), which substantially confirm the main findings presented there. Attention is drawn to the fact that easier hiring and firing procedures, which result in shorter job tenures, inhibit the formation of firm-specific, “tacit” knowledge and hinder the functioning of the “routinized” innovation model (Vergeer and Kleinknecht 2014, p. 383).

Lucidi and Kleinknecht (2010) identify four channels through which labor flexibility can lead to a poor performance in labor productivity growth: a) in the spirit of the works of Sylos-Labini and Schumpeter, (a lack of) flexibility induces the adoption of capital-intensive techniques of production and favors a process of creative destruction, pushing non-innovators, who are unable to cope with a higher cost of labor and tighter regulations out of the market; b) short-term labor relations lead to under-investment in workforce training; c) better job protection prevents the creation of a conflictual working environment, helps with the establishment of more cooperative industrial relations and elicits employees’ commitment and trust; d) flexible and precarious jobs are conducive to low wages, so if an economy is wage-led (Bhaduri and Marglin 1990), this causes a slowdown in aggregate demand and consequently in the dynamics of labor productivity, according to the Kaldor-Verdoorn law (Verdoorn 1949; Kaldor 1978). The authors conclude their analysis, focused on the Italian case, finding that the Italian labor market reforms “shifted Italy towards … a labour-intensive and low-productive growth path” (Lucidi and Kleinknecht 2010, p. 541).

Kleinknecht et al. (2016) detail a further argument to support the view that flexibility may damage labor productivity: firms with a higher share of “flexible” workers tend to have higher shares of non-productive, managerial personnel. Higher labor turnover and easy firings result in a lack of trust that must be compensated for by greater levels of control.

In DosiFootnote 17 et al. (2017), the authors incorporate an explicit analysis of labor market flexibilization into their ‘Schumpeter meeting Keynes’ Agent Based Model (ABM) model.Footnote 18 They conclude that reforms oriented to this goal contribute to increased levels of inequality and a higher rate of unemployment, with no gain in terms of the long-term growth of productivity. A more flexible labor market, indeed, restrains the operating of the “Schumpeterian engine of innovation and growth” (Dosi et al. 2017, p. 25).

There is also a sizable stream of literature that directly addresses a specific feature of labor market flexibility, namely, the liberalization and widespread diffusion of temporary contracts. Daveri and Parisi’s (2015) study of the relationship between employees’ experience, productivity and innovation conclude that “firms endowed with a high share of temporary workers always exhibit lower productivity growth, no matter what its innovation activity” (Daveri and Parisi 2015, p. 903).

Blanchard and Landier (2002) identify a potential “perverse” effect of the liberalization of fixed-term contracts: after the expiration of the temporary contract, even if the match between the temporary worker and the employer is productive, the latter could still opt for replacing the former with a new worker under a temporary contract instead of issuing a regular contract to the former employee because this would enhance her bargaining position and allow her to gain a higher wage. The result is that firms can be induced to “design routine, low-productivity jobs, which they can fill through the use of fixed-term contracts” (Blanchard and Landier 2002, p. 244).

Battisti and Vallanti (2013) find that a larger share of temporary workers within the firm is detrimental to workers’ effort - studied in terms of absenteeism - and hence to firm-level productivity. In Cappellari et al. (2012), the negative influence of temporary workers on the dynamics of productivity operates by activating a substitution of workers for capital, negatively affecting the capital/labor ratio.Footnote 19 Cirillo et al. (2017) discuss the effects on several dimensions of the labor market of a recent Italian reform (the so-called ‘Jobs Act’) that, among other things, heavily liberalized the terms for the use of fixed-term contracts. Perhaps the most interesting finding points to a strong bias toward the creation of new jobs, which tend to be mostly concentrated in low-tech, low-innovation, precarious-job service sectors.Footnote 20 Moving the analysis to the European level, Cirillo and Guarascio (2015, p. 160) maintain that such “cost competitiveness strategies aiming to compete by reducing labour costs weaken the foundation for a technological upgrade of the economy”.Footnote 21

Boeri and Garibaldi (2007) investigate the consequences of the introduction of an employment “two-tier regime,” which allows firms to hire both permanent and temporary workers. Their theoretical model predicts a permanent fall in average productivity, due to the functioning of the law of diminishing returns: the possibility of hiring workers under a fixed-term contract stimulates employment, which, however, expands in a region of the demand curve where marginal productivity is decreasing. They also validate their result through an empirical analysis, which stresses “the negative effect of the spread of fixed term contracts on labour productivity” (Boeri and Garibaldi 2007, p. 378).

Drawing from this literature review, we include “temporary employees as a percentage of the total number of employees,” as a proxy for labor market flexibility, among the determinants of labor productivity growth, expecting that there will be a negative influence on the latter of our variables of interest.Footnote 22

4 Toward a model of labor productivity: Institutions, investment and innovation

John Maynard Keynes’ work focuses on the role of aggregate demand -and, in particular, of investment and government expenditures- in determining the level of employment, income and production. Technical progress, on the other hand, is not a main concern of the British economist.

With few exceptions, on the other hand, both endogenous growth models (Romer 1990; Dinopoulos and Segerstrom 1999) and evolutionary models (Nelson and Winter 1982) are driven by Schumpeterian characteristics with endogenous innovation, but do not take into consideration demand dynamics and the interaction between innovation and aggregate demand. Among the exceptions we hinted at, it is worth mentioning Dosi et al. (2010) – and more generally the ‘Keynes meets Schumpeter’ class of models developed by Dosi and co-authors - who present an Agent Based Model (ABM) that is evolutionary rooted and explores the influence of aggregate demand and the endogenous drivers of technical progress.

At the intersection between Keynes and Schumpeter, one can find the “technical production function” of Kaldor (1961),Footnote 23 which depends on investment and on “society’s ‘dynamism,’ meaning by this both inventiveness and readiness to change and to experiment” (ibid., p. 208). In fact, the technical progress function of Kaldor, represented below in eq. (1), has two components: the first has an exogenous nature and is given by the parameter α, identified with “society’s dynamism,” while the second part of the equation, βgk, states that the evolution of labor productivity is a positive function of the rate of growth of capital per worker k.Footnote 24

The rationale is the following: given that most technical innovations and improvements are incorporated into machinery and equipment, for any given level of society’s dynamism and inventiveness, the economy can absorb only a bounded amount of technical change, which is an increasing function of the speed with which capital is accumulated.

In Schumpeter and in the neo-Schumpeterian tradition, the creation and incorporation of technology depend on the economy’s existing institutional arrangements (Romero 2014). Hence, the α of Kaldor’s equation and its possibility to be continuously translated at a higher level depend on institutions, norms, rules and behavior identified generally with “society’s dynamism,”

Kaldor (1970) provides another important element of connection with the evolutionary approach, which is the notion of ‘cumulative causation’: a self-reinforcing dynamic in the circular process of investment demand leading to innovation and stimulating further investment. As Courvisanos states (2012, p. 297), R&D expenditure is crucial in the endogenous innovation process,Footnote 25 where, in particular, large firms spend more on R&D and activate more patents and innovation routes, while exogenous innovation refers to technological paradigm shift. This is the reason why, in our econometric model, R&D along with general investment are both crucial in generating productivity gains.

This cumulative process is also present in the notion of path dependency of most evolutionary models, for which the pioneer was Veblen (1919) in his theory of cumulative change. In Veblen, cumulative change explains the dynamic of progressive institutional change.Footnote 26 In essence, it starts with technological innovation, which alters habits and behaviors in a community which in turn, creates further innovation in the sciences. Following the logic of Veblen, institutional change moves from technological change to following a cumulative process.

Veblen’s (and Kaldor’s) idea of cumulative change is also the basis for any formal change. The institutional framework adapts to the new technological systems. However, the uncertainty of profits that a technological shift may generate could push firms toward resistant behavior and lobbying against the changes. That is why Veblen argues that technological innovation alters habits, both directly and indirectly, through changes in the formal framework and resistance in the informal behavior. Large corporations with the direct or indirect support of states may wish to protect the old technological paradigm in order to defend existing capital value. This may generate institutional tension and also rates of labor productivity growth that differ from one sector to another. At the macro level, one can have limitations of the scale of production that can lead to a decline in economic development, despite (fragmented and unintegrated) technological progress having occurred (Rosenberg 1972, 1976).

5 The model

Drawing from the theoretical background put forward in the paper and, in particular, in the second, third and fourth sections, we are going now to test the main implications of our theoretical analysis through a simple econometric model that relies on a set of 25 EU countries in the period between 1995 and 2016. This was a very important periodFootnote 27 for technological change and innovation. Most advanced economies went through a radical shift in their technological paradigm during this period that dramatically changed their production techniques and products and accelerated the shift of employment toward service industries. The knowledge-based economy was simultaneously consolidated and new forms of digitalization and robotization of the economy seemed to take place, in particular after the financial crises of 2008–09. Moreover, an increasing number of firms (and sometimes governments) seem to have understood the crucial role played by R&D.Footnote 28

The model that we are going to estimate on our panel (25 EU countries in the period between 1995 and 2016), with a dynamic labor productivity growth equation, is as follows:

Where:

-

\( {\dot{LP}}_{it} \) is the rate of growth of labor productivity per hour worked (i.e. real value added per hour worked), for the whole economy;

-

\( \dot{INV} \)it is the rate of growth of non-residential investmentFootnote 29 (both public and private) in real terms; we expect βs coefficients to be positive, since investment growth should reflect increasing capital stock. As mentioned in Section 4 when discussing Kaldor’s technical progress function, technical innovations and improvements tend to be incorporated into machinery and equipment. For this reason, capital accumulation is likely to exert a positive influence on technical progress and on the dynamics of labor productivity;

-

\( {\dot{R\&D}}_{it} \) is the rate of growth of R&D investment (both public and private); we expect βk coefficients to be positive. R&D growth should reflect increasing knowledge accumulation or, using Kaldor’s words, the dynamism of a society in terms of ideas. This contributes, for given levels of the capital stock, to the activation of endogenous innovation processes and of innovation routes, as in the Schumpeterian theoretical tradition;

-

Mseit is the share of employment in the manufacturing sector, as hours worked; we expect this variable to affect positively our variable of interest. Based on the literature reviewed in Section 2, the gradual abandonment of manufacturing can produce a drag on labor productivity growth. This sector, indeed, generates relatively high innovation spillovers; most technological innovations are embodied in manufactured capital goods and, finally, the size of the manufacture sector is traditionally conducive to larger economies of scale;

-

Sseit is the share of employment in the skilled service sectors (Information and Communication, Financial, Insurance and Real Estate activities, Professional Business Services), as hours worked. Based on the literature reviewed in Section 2 – see, for example, Maroto and Rubalcaba (2008) and Maroto-Sánchez and Cuadrado-Roura (2009) - one might expect the impact of this variable to be positive;

-

BDseit is the share of employment – in terms of hours worked - in the following industries: Food and Accommodation, Logistics and Social Services, which we label “Baumol’s disease” service industries. We expect BDse to affect labor productivity growth negatively since, as pointed out, for example, in Wölfl (2005), specific obstacles to innovation might exist, from there being an average small size of firms in these industries to the difficulties of gathering the finance necessary to invest in high-risk, high-tech capital stock. Low investments in R&D and in workforce training also contribute to the expectation of a negative relationship between employment in these industries and labor productivity growth;

-

TWit is the share of temporary employeesFootnote 30 in total employment; we expect TW to affect labor productivity growth negatively, since flexible, less well-paid jobs (usually precarious) are often used by firms as a substitute for technological improvements, within a strategy of labor cost competitiveness, as demonstrated also by Sylos Labini.Footnote 31 The share of temporary employees is the proxy we chose for labor flexibility since, as noted in Boeri and Garibaldi (2007) and Cappellari et al. (2012), labor flexibilization in most European countries has been taking place mostly through the liberalization of the terms for the use of temporary contracts.Footnote 32

-

δt denotes year-trend dummies; notice that we use random effect models with respect to the panel variable and year-trend dummies to deal with common time-related shocks and thus to remove correlations in errors across countries.

Finally, some control variables were used, such as:

-

INV/GDPit is the share of non-residential investment in GDP

-

R&D/GDPit is the level of R&D expenditures, performed by all sectors, as a percentage of GDP

-

LPconvit is labor productivity level of country i, expressed as a percentage of the labor productivity level of EU28 countries as an aggregate

-

εit denotes the error term.

In Table 1, we summarize the discussed variables and their expected impact on labor productivity growth. In Table 2, we report the results, which refer to six different model specifications, estimated by means of a GLS-based (random effect) regression. In detail, we first estimated the baseline model (column I). Then, we extended the analysis (column II), introducing also a dummy-year variable; the results are consistent with those of the baseline model. In column III, a regular time fixed effect was introduced and results of the baseline are not altered. Column IV also reports an OLS model. In column V, we included among the regressors, the lagged value of the dependent variable, while in column VI we added three more control variables to the model: 1) to control for some degree of convergence, we included the level of country i’s labor productivity as a percentage of the EU28 labor productivity level. Moreover, we control for 2) the (non-residential) investment to GDP ratio and to capture a broader picture of a country’s commitment to R&D, 3) R&D expenditures as a percentage of GDP.Footnote 33

The inclusion of these control variables does not alter the main insights of the baseline model. Indeed, these are statistically not significant. The speed of total and R&D investment seems to be what matters for the growth of labor productivity. This is also consistent with the Schumpeterian and Kaldorian theoretical approaches proposed and discussed earlier. The hypothesis of convergence - i.e., that a country the labor productivity level of which is relatively low should grow faster- is not confirmed, since the coefficient of labor productivity level (as a percentage of EU28 labor productivity) is not statistically significant. Finally, according to the Hausman test, reported in the Appendix in Table 5, the random effect estimates are consistent. The F-test in Model IV suggests not to include a time trend, despite the fact that, in Model III, with a time fixed effect, between the variance of Rsquared increases, the between variance remains very high, and explains most of the variation among countries, while the within variance left unexplained is smaller.

Moreover, we performed a bi-variate causality test (Granger 1969) – based on a panel vector autoregression methodology (see Abrigo and Love 2016) – between labor productivity growth and each of the independent variables used in the baseline model. As shown in Table 6 in the Appendix, we can reject the null hypothesis that the set of independent variables of our model does not Granger-cause LP growth.

In addition to the usual regression statistics, some diagnostic issues were also explored. Since we have to deal with a relatively small (imperfect) collinearity among some predictors, as well as the fact that some endogeneity concerns can be advanced, we carried out a variance inflation factor (VIF) test, which aims to exclude systematic multicollinearity among explanatory variables; see also the correlation Table 7 in the Appendix. Notice that when VIF is high, there is high multicollinearity, and consequently regression coefficients would be unstable. Despite the fact that there are no formal thresholds for determining the presence of multicollinearity, the higher the VIF values, the greater the correlation of the variable with others. Values of more than four or five are sometimes regarded as being moderate to high, and values higher than 10 are often regarded in the literature as indicating multicollinearity. As can be seen in Table 8, the highest VIF value in our econometrics is 1.98 (while the VIF mean is 1.38) and since higher values signify that it is difficult or almost impossible to assess accurately the contribution of predictors to a model, we can exclude collinearity and state, with a higher degree of certainty, that multicollinearity is not biasing the estimated coefficients. A unit root test was also used (Im-Pesaran-Shin) to verify whether the panel data contains unit roots or if it is stationary. The null hypothesis tested, which we reject with a level of significance (p value 0.000), is that the series contains a unit root and the alternative hypothesis is that the series is stationary (see Table 9 in the Appendix). Last, but not least, the residual normality test (see the Kernel test in Fig. 3 in the Appendix) confirms a symmetric and unimodal distribution.

The econometric exercises seem to substantiate the four channels determining the dynamics of labor productivity that we listed in the introduction. First of all, the speed of investment measured by the rate of investment growth, which has a positive impact on labor productivity growth as expected. Second, the speed of R&D investment, measured by the rate of investment in R&D, which also has a positive impact on labor productivity. Third, the flexibility of the labor market, captured by the increase of temporary employment, which has a negative impact on the dynamics of labor productivity, as predicted by the literature discussed in Section 3. Fourth, the direction of structural change: an increase in the share of employment in manufacturing sustains labor productivity growth, while the share of employment in the “Baumol’s disease” service sector has a negative influence on the evolution of this variable, providing some evidence to support the hypothesis of the persistence of the so-called Baumol’s disease. On the other hand, the impact exerted by the skilled service sector – at least in our analysis - is not so straightforward: the sign of the coefficient is negative but not significant. The message, anyway, is clear in our view: countries should avoid a specialization toward the service industries affected by Baumol’s disease, which has a very limited potential for productivity gains.Footnote 34

6 Concluding remarks

In recent decades, many advanced economies have witnessed unsatisfying performances in terms of labor productivity growth, during a process of institutional and structural change. At first glance, this may appear puzzling. In the same time period, we have also witnessed a generalized application of all the ingredients that, according to most “supply-side” economists and international institutions,Footnote 35 should have modernized and enhanced the competitiveness of dynamic and growing economies: labor market flexibilization and, more generally, structural labor market reforms, downsizing of the welfare state, market deregulation, privatizations and so on. However, what we have in fact observed is a prolonged, almost worldwide productivity slowdown. In the face of this evidence, a major challenge for mainstream economics arises: how to explain that, after decades of “structural reforms”, the majority of advanced economies are trapped in an extended productivity stall?

In this article, we have attempted to identify possible causes of this slowdown. We consider it plausible that physical investment is a key determinant of technical progress. We have also singled out a particular category of investment, R&D investment, because this expenditure is crucial in the endogenous innovation process. The share of temporary employees in total employment, as has been found consistently in the relevant literature, is likely to act as a drag on labor productivity. Among other things, labor flexibility also tends to be associated with the creation of low-wage, low-productivity jobs. In this respect, it is interesting to notice that these “Baumol’s disease” jobs are often concentrated in productive sectors that have limited exposure to international competition and trade, a feature that should induce further reflection on the globalization-productivity slowdown link frequently identified in the literature. All these trends have been discussed in the context of the ongoing radical change in the productive structures of advanced economies, namely, the gradual abandonment of manufacturing and the multifaceted process of tertiarization.

We submitted our hypotheses, sketched briefly above, to empirical scrutiny, by means of a panel data analysis of 25 European countries and the results are broadly consistent with the theoretical argument put forward in Sections 2–4. The results are obviously not conclusive and further research is needed, in particular to clearly disentangle different contributions to labor productivity growth given by the specialization in different service industries. The role of the State in fostering innovation and the need for appropriate financing instruments to fund private innovation expenditures should also be explored to enrich the picture we tried to depict in this article.

Finally, some policy recommendations can be drawn: the global economy is undergoing a radical process of change, which affects productive structures and the international division of labor. These trends cannot be easily reverted but need to be governed. The need for coordinated industrial policy is becoming increasingly recognized and established. On the one hand, as noted in Mazzucato et al. (2015, p. 140), a well-designed industrial policy can drive the economy toward research into improvements in static and dynamic efficiency and enhance firms with better learning processes and a higher potential for technological progress, to incentive specialization in commodities (and services) for which global demand is robust and steady. This is, however, only one side of the story. Dosi et al. (2010) remind us that Schumpeterian policies, which aim at generating endogenous innovations, are a necessary but not sufficient condition to maintain the economy on a high-growth, high-productivity path. Fiscal policies and stimuli to aggregate demand, identified by Dosi et al. (2010, p. 1755) as the “Keynesian engine,” exert a strong complementarity with and are the natural companion to the Schumpeterian engine.

Notes

A partial exception is represented by Central and Eastern European countries, where the growth of labor productivity has, to an extent, flattened, but at generally higher rates. It is not, however, the purpose of this article to discuss the differences and specificities of each country and/or their welfare models.

The sixteen countries in Figure 1 are a sub-sample of the countries in our empirical analysis.

See Gordon (2016) for a discussion centered on the US case, which lies outside the scope of this work. In his book, the author argues convincingly that the wave of technological improvements that has characterized the last decades, namely the IT “revolution”, does not have the same potential for long-term growth as did Great Inventions from the past (e.g., electricity or the internal combustion engine). Hence, contemporary economies are stuck in a state of technological stagnation, made worse by the contemporaneous issues of increasing income inequality, aging populations and other “headwinds”.

We will refer, throughout the article, to a broad definition of institution, which relates to “conventions, customs, habits of thinking and modes of doing which make up the scheme of arrangements which we call ‘the economic order’” and also with the way in which institutions interact to comprise “the organization of modern industrial society” (Hamilton 1919, p. 311).

See Tridico and Pariboni (2017) for some descriptive evidence.

We will not discuss the causes behind this process here. See Autor et al. (2013) for an analysis of the impact of Chinese import competition on the US labor market. Rodrik (2016) identified globalization and labor-saving technical progress as the main explanatory factors for employment loss in manufacturing in advanced economies. See also Schettkat and Yocarini (2006) for a thorough review of the literature on the ‘tertiarization’ of advanced economies, in which the authors uncover three main explanations: differentials in productivity growth among industries (more on this later, in the discussion of Baumol’s contribution); shifts in the inter-industry division of labor and the increasing importance of outsourcing from the manufacturing to the service industries; finally (and this is the one preferred by the authors) “the shift to services in the advanced economies is a real shift in final demand” (Schettkat and Yocarini 2006, p. 145).

Throughout this article, we use the term deindustrialization to encapsulate the relative loss of importance and weight of manufacturing. However, as noted in Szirmai (2012), according to the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC), the industrial sector also comprises mining, utilities and construction. Here, we will follow Szirmai (as well as the standard use) and refer to a narrower concept that incorporates only the manufacturing industry.

The 25 countries in our sample are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Due to a lack of data availability, we had to drop Croatia, Malta, Poland and Spain from our analysis.

See Table 10 in the Appendix, for a summary of the arguments put forward in this section.

See Griliches (1994), Hartwig (2008) and Harchaoui (2016). On the other hand, see also Byrne et al. (2016), where it is convincingly argued that the observed labor productivity slowdown does not arise “from growing mismeasurement of the gains from innovation in information technology-related goods and services” (Byrne et al. 2016, p. 109) and Syverson (2017). In both Byrne et al. (2016) and Syverson (2017), it is also stressed that “nonmarket” benefits, in terms of consumer surpluses and estimated gains in nonmarket production that arise from the adoption of IT technologies, do not compensate for the productivity slowdown, which remains sizable even when taking these factors into account.

Similar arguments are made in Wölfl (2005).

See Maroto-Sánchez and Cuadrado-Roura (2009) and Wölfl (2005) for an analysis of productivity differentials among different service sub-sectors. See also Daniels et al. (2011) and Di Meglio et al. (2015), among others, who try to relate the debate on structural change –and its peculiar directions in different institutional contexts– to the ‘Varieties of Capitalism’ approach.

See Table 11 in the appendix for a summary.

The argument is, obviously, far from uncontroversial. See, for example, Nickell and Layard (1999); Saint-Paul (2000), Bassanini and Ernst (2002) or Scarpetta and Tressel (2004) for an opposite view on the relationship between labor flexibilization and productivity. See also Vergeer and Kleinknecht (2010) and Lucidi and Kleinknecht (2010) for a rebuttal of the theses presented in these works.

The authors mention “capital-labor substitution, vintage effects, induced technical change, creative destruction and demand-pull effects” (Vergeer and Kleinknecht 2010, p. 393).

Dosi and co-authors have developed, along several years, an innovative stream of research, wherein the analytical tool used is a class of models labeled as ‘Keynes meets Schumpeter’.

With this expression, we refer to “a model in which a multitude of (heterogeneous) elements or objects interact with each other and the environment” (Delli Gatti and Gallegati 2018, p. 7).

See also Jona Lasinio and Vallanti (2013, p. 22).

Jona Lasinio and Vallanti (2013) develop a similar argument with respect to the effects of the diffusion of temporary contracts. See also Auer et al. (2005), where the authors find a positive correlation between employment tenure and labor productivity, as job stability (as opposed to a short-term contract) is necessary for job training.

A similar argument is made in Storm and Naastepad (2015).

As Boeri and Garibaldi (2007) notice, in most European countries, the increase in labor flexibility has been taking place mainly through the liberalization of the terms for the use of temporary contracts.

See also Tridico and Pariboni (2018) for a recent discussion.

It should be remembered that Kaldor’s treatment of capital in the context of the “technical progress function” is subject to serious criticism, related to the aggregation problem and to the utilization of “a measure of capital as a homogeneous physical quantity” (McCombie and Spreafico 2016, p. 1124), despite the results of the Cambridge controversy on capital. See McCombie and Spreafico (2016) for a detailed discussion of these issues and for a restatement of Kaldor’s insights on growth and productivity.

See also the work of Clarence Ayres (Ayres 1944) for an early and prescient evolutionary view of technology and, in particular, for the analysis of the dichotomic relationship between the dynamic behavior of technology and the static behavior of institutions, the nature of which can hinder technological change

This very same period can be, ideally, split into two sub-periods: the first one, up to around 2003–2004, experienced relatively intense productivity growth, mostly driven by the information technology boom. However, in the last 14–15 years, productivity growth has again been on a mostly stagnant path (see Gordon 2016 for a detailed and insightful analysis with respect to the US).

We subtract, from total non-residential investment, the R&D investment, which is considered independently.

Based on the Eurostat definition, “[t]emporary employment includes work under a fixed-term contract, as against permanent work where there is no end-date” (Eurostat Glossary).

See, for example, Sylos Labini (1999).

This finding is confirmed by an analysis of trends in the EPL (Employment Protection Legislation) indexes, developed by the OECD. The EPL for temporary contracts steadily decreases for most countries during the time span covered by the available data, while the EPL for regular contracts displays a flatter pattern. However, the last year for which the EPL time series are available is 2013 and, also for this reason, we prefer to include the share of temporary employees as our measure of labor flexibility. See Section 3 for a review of the literature.

See also Table 4 in the Appendix, where we present the results of further robustness checks. In column I, following the suggestion of a referee, we replace the rates of growth of non-residential investment and of R&D investment with the rate of growth of an overall variable that encompasses both. In other words, totINV = INV + R&D, where we defined INV as non-residential real gross fixed capital formation, excluding R&D real gross fixed capital formation (real gross fixed capital formation, total assets minus real gross fixed capital formation, dwellings minus real gross fixed capital formation, Research and Development). See also Table 3 in the Appendix. In column II we restrict the analysis to the Eurozone countries (although the countries in our sample are 17, due to the lack of some data for Spain and Malta). The main difference with the rest of the empirical analysis is that the positive and significative coefficient attributed to employment in the ‘skilled services’ sector becomes significant, while the coefficient of temporary workers is no longer significant.

In this respect, a lesson can also be drawn from the growing body of literature on economic complexity. Even if this is not the main purpose of this paper, it should be recalled that, according to this literature, countries should pursue a strategy oriented towards complex, sophisticated production, given its likely positive impact on output and productivity growth and the stimulus it provides to technology and technological capabilities (see for example Hidalgo et al. 2007; Hidalgo and Hausmann 2009 or Gräbner et al. 2017). It is reasonable to imagine that complex products tend to be the outcome of specific branches of the manufacturing industry.

See Storm and Naastepad (2015) for an overview.

References

Abrigo MR, Love I (2016) Estimation of panel vector autoregression in Stata. Stata J 16(3):778–804

Auer P, Berg J, Coulibaly I (2005) Is a stable workforce good for productivity? International Labour Review 144(3):319–343

Autor DH, Dorn D, Hanson GH (2013) The China syndrome: local labour market effects of import competition in the United States. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2121–2168

Ayres CH (1944) [1962] The theory of economic Progress. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Bassanini A, Ernst E (2002) Labour market institutions, product market regulation, and innovation: cross-country evidence. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 316

Battisti M, Vallanti G (2013) Flexible wage contracts, temporary jobs, and firm performance: evidence from Italian firms. Ind Relat 52(3):737–764

Baumol WJ (1967) Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis. Am Econ Rev 57(3):415–426

Baumol WJ (2002) Services as leaders and the leader of the services. In: Gadrey J, Gallouj F (eds) Productivity, innovation and knowledge in services. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 147–163

Baumol WJ, Bowen WG (1965) On the performing arts: the anatomy of their economic problems. Am Econ Rev 55(1/2):495–502

Baumol WJ, Batey Blackman SA, Wolff EN (1989) Productivity and American leadership. In: The long view. MIT Press, London

Bhaduri A, Marglin S (1990) Unemployment and the real wage: the economic basis for contesting political ideologies. Camb J Econ 14(4):375–393

Blanchard O, Landier A (2002) The perverse effect of partial labour market reforms: fixed-term contracts in France. Econ J 112(480):214–244

Boeri T, Garibaldi P (2007) Two-tier reforms of employment protection legislation: a honeymoon effect? Econ J 117(521):357–385

Byrne DM, Fernald JG, Reinsdorf MB (2016) Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem? Brook. Pap. Econ. Act 47(1):109–157

Cappellari L, Dell’Aringa C, Leonardi M (2012) Temporary employment, job flows and productivity: a tale of two reforms. Econ J 122(562):188–215

Cirillo V, Guarascio D (2015) Jobs and competitiveness in a polarised Europe. Intereconomics 50(3):156–160

Cirillo V, Fana M, Guarascio D (2017) Labour market reforms in Italy: evaluating the effects of the jobs act. Econ Polit 34(2):211–232

Courvisanos J (2012) Innovation. In: King JE (ed) The Elgar companion to post Keynesian economics, second edition. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 294–299

Daniels P, Rubalcaba L, Stare M, Bryson J (2011) How many Europes? Varieties of capitalism, divergence and convergence and the transformation of the European services landscape. Tijdschr Econ Soc Geogr 102(2):146–161

Daveri F, Parisi ML (2015) Experience, innovation, and productivity: empirical evidence from Italy’s slowdown. International Labour Review 68(4):889–915

Delli Gatti D, Gallegati M (2018) Introduction. In: Delli Gatti D, Fagiolo G, Gallegati M, Richiardi M, Russo A (eds) Agent-based models in economics a toolkit. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–9

Di Meglio G, Pyka A, Rubalcaba L (2015) On the “how many Europes” debate: varieties of service economies. Tijdschr Econ Soc Geogr 106(3):307–320

Dinopoulos E, Segerstrom P (1999) A Schumpeterian model of protection and relative wages. Am Econ Rev 89:450–472

Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Roventini A (2010) Schumpeter meeting Keynes: Apolicy-friendly model of endogenous growth and business cycles. J Econ Dyn Control 34(9):1748–1767

Dosi G, Pereira MC, Roventini A, Virgillito ME (2017) The effects of labour market reforms upon unemployment and income inequalities: an agent-based model. Soc Econ Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx054

Edquist H, Henrekson M (2017) Do R&D and ICT affect total factor productivity growth differently? Telecommun Policy 41(2):106–119

Engel D, Rothgang M, Eckl V (2016) Systemic aspects of R&D policy subsidies for R&D collaborations and their effects on private R&D. Ind Innov 23(2):206–222

Eurostat Glossary (n.d.-b) definition of Temporary Employment, available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Temporary_employment

Fagerberg J, Verspagen B (2002) Technology-gaps, innovation-diffusion and transformation: an evolutionary interpretation. Res Policy 31(8–9):1291–1304

Gordon RJ (2016) The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gräbner C, Heimberger P, Kapeller J, Schütz B (2017) Is Europe disintegrating? Macroeconomic divergence, structural polarization, trade and fragility. ICAE Working Paper no 64

Granger CWJ (1969) Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 37(3):424–438

Griffith R, Redding S, Van Reenen J (2004) Mapping the two faces of R&D: productivity growth in a panel of OECD countries. Rev Econ Stat 86(4):883–895

Griliches Z (1994) Productivity, R&D, and the data constraint. Am Econ Rev 84(1):1–23

Hamilton WH (1919) The institutional approach to economic theory. Am Econ Rev 9(1):309–318

Harchaoui TM (2016) The Europe-U.S. productivity gap in a rear-view mirror: will measurement differences in the services sector output please rise? J Econ Surv 30(1):93–116

Hartwig J (2008) Productivity growth in the service industries: are the transatlantic differences measurement drive? Rev. Income Wealth 54(3):494–505

Hartwig J (2011) Testing the Baumol-Nordhaus model with EU KLEMS data. Rev. Income Wealth 57(3):471–489

Hidalgo CA, Hausmann R (2009) The building blocks of economic complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106(26):10570–10575

Hidalgo CA, Klinger B, Barabási A-L, Hausmann R (2007) The product space conditions the development of nations. Science 317(7):482–487

Jona Lasinio C, Vallanti G (2013) Reforms, labour market functioning and productivity dynamics: a sectoral analysis of Italy, Government of the Italian Republic, Ministry of Economy and Finance, department of the Treasury Working Paper no 10

Kaldor N (1961) Capital, accumulation and economic growth. In: Lutz FA, Hague DC (eds) The theory of capital. St. Martin’s Press, New York, pp 177–222

Kaldor N (1966) Causes of the slow rate of economic growth in the United Kingdom. Cambridge University Press, London

Kaldor N (1970) The case for regional policies. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 17(3):337–348

Kaldor N (1978) Further essays on economic theory. Duckworth, London

Kleinknecht A, Kwee Z, Budyanto L (2016) Rigidities through flexibility: flexible labour and the rise of management bureaucracies. Camb J Econ 40(4):1137–1147

Lucidi F, Kleinknecht A (2010) Little innovation, many jobs: an econometric analysis of the Italian labour productivity crisis. Camb J Econ 34(3):525–546

Marglin SA, Schor JB (eds) (1990) The Golden age of capitalism. Rethinking the postwar experience. Clarendon, Oxford

Maroto A, Rubalcaba L (2008) Services productivity revisited. Serv Ind J 28(3):337–353

Maroto-Sánchez A, Cuadrado-Roura JR (2009) Is growth of services an obstacle to productivity growth? A comparative analysis. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 20(4):254–265

Mazzucato M (2016) From market fixing to market-creating: a new framework for innovation policy. Ind Innov 23(2):140–156

Mazzucato M, Cimoli M, Dosi G, Stiglitz J, Landesmann M, Pianta M, Walz R, Page T (2015) Which industrial policy does Europe need? Intereconomics 50(3):120–155

McCombie JSL, Spreafico M (2016) Kaldor’s ‘technical progress function’ and Verdoorn’s law revisited. Camb J Econ 40(4):1117–1136

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An evolutionary theory of economic change. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nickell S, Layard R (1999) Labor market institutions and economic performance. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 3029–3084

Rodrik D (2011) The manufacturing imperative. In: Project syndicate available at https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-manufacturing-imperative?barrier=accessreg

Rodrik D (2016) Premature deindustrialization. J Econ Growth 21(1):1–33

Romer PM (1990) Endogenous technical change. J Polit Econ 98(5):71–102

Romero JP (2014) Mr. Keynes and the neo-Schumpeterians: contributions to the analysis of the determinants of innovation from a post-Keynesian perspective. EconomiA 15(2):189–205

Rosenberg N (1972) Factors affecting the diffusion of technology. Explor Econ Hist 10(1):3–33

Rosenberg N (1976) On technological expectations. Econ J 86(343):523–535

Saint-Paul G (2000) The political economy of labour market institutions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Salop SC (1979) Monopolistic competition with outside goods. Bell J Econ 10(1):141–156

Scarpetta S, Tressel T (2004) Boosting productivity via innovation and adoption of new technologies: any role for labor market institutions?, World Bank Research Working Paper no WPS 3273

Schettkat R, Yocarini L (2006) The shift to services employment: a review of the literature. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 17(2):127–147

Shapiro C, Stiglitz JE (1984) Equilibrium unemployment as a worker discipline device. Am Econ Rev 74(3):433–444

Storm S, Naastepad CWM (2012) Macroeconomics beyond the NAIRU, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012

Storm S, Naastepad CWM (2015) Europe’s hunger games: income distribution, cost competitiveness and crisis. Camb J Econ 39(3):959–986

Sylos Labini P (1999) The employment issue: investment, flexibility and the competition of developing countries. BNL Quarterly Review 52(210):257–280

Syverson C (2017) Challenges to mismeasurement explanations for the US productivity slowdown. J Econ Perspect 31(2):165–186

Szirmai A (2012) Industrialisation as an engine of growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 23(4):406–420

Szirmai A, Verspagen B (2015) Manufacturing and economic growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 34(3):46–59

Tridico P, Pariboni R (2017) Structural change, aggregate demand and the decline of labour productivity: a comparative perspective, Dipartimento di Economia (Roma Tre University) Working Paper no 221

Tridico P, Pariboni R (2018) Inequality, financialization and economic decline. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 41(2):236–259

Triplett, J.E. and Bosworth, B. (2003), Productivity measurement issues in services industries: "Baumol's disease" has been cured, Economic Policy Review, Sep, 23-33

Veblen T (1919) The place of science in modern civilisation and other essays. Huebsch, New York

Verdoorn PJ (1949) Fattori che Regolano lo Sviluppo della Produttività del Lavoro. L’Industria 1(March):3–10

Vergeer R, Kleinknecht A (2010) The impact of labor market deregulation on productivity: a panel data analysis of 19 OECD countries (1960-2004). Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 33(2):371–408

Vergeer R, Kleinknecht A (2014) Do labour market reforms reduce labour productivity growth? A panel data analysis of 20 OECD countries (1960-2004). International Labour Review 153(3):365–393

Wölfl A (2005) The service economy in OECD countries’, OECD science, technology and industry working papers 2005/03

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Walter Paternesi Meloni, three anonymous referees and participants in the 29th EAEPE Annual Conference at Corvinus University of Budapest, the 40th Villa Mondragone International Economic Seminar and in a seminar at the Department of Economics, Roma Tre University for helpful comments and constructive criticisms. The usual disclaimer applies.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pariboni, R., Tridico, P. Structural change, institutions and the dynamics of labor productivity in Europe. J Evol Econ 30, 1275–1300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-019-00641-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-019-00641-y