Abstract

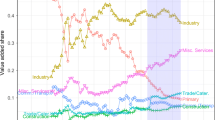

The purpose of this study is to empirically examine the relationship between structural change and economic growth in Japan during the past 40 years. Using growth in real value added and labour productivity as measurements of economic growth, we consider the structural change in value added as the structural change in output and that in capital and labour as the structural change in inputs. Specifically, we use the Japan Industrial Productivity database 2014 compiled by the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, and show (1) the pace of structural change in inputs and output, (2) the evolution of sectoral dispersion of economic performance, (3) the changing distribution of sectoral contribution to aggregate economic growth, and (4) empirical evidence of the relationship between structural change and economic growth. Our main conclusion is that since the 1990s, the Japanese growth regime has transformed from a regime with decreased heterogeneity and overall growth process to a regime with increased heterogeneity and an uneven growth process. In addition, there has been a positive impact of structural change in output on economic growth, although its magnitude has weakened since then.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Study by Krüger (2008a) is a comprehensive survey on structural change, economic growth, and productivity. The study reviews the development of the classical three-main sector model, multi-sector growth models, evolutionary theories, and empirical studies.

So-called de-industrialization is a well-known example of such structural change. According to the related literature (e.g. Rowthorn and Wells 1987), ‘de-industrialization’ means the decreasing share of employment in the industrial (manufacturing) sector.

Ansari et al. (2013) introduce the modified Lilien measure as a desirable indicator of structural change that ideally fulfils the following five necessary conditions: (1) the index should take the value of zero if there are no structural changes within one period, (2) the structural change between two periods should be independent of the time sequence, (3) the structural change in one period should be smaller or equal to that between two sub-periods, (4) the index should be a dispersion measure, and (5) the index should consider the weight (size) of the sectors. The Lilien index violates conditions (2) and (3), whereas the modified Lilien index fulfils all the necessary conditions.

Moreover, the final demand by sector in the JIP database input–output table is appropriate to capture the demand-side dynamics. However, since some data of demand components are not available in this table, we cannot conduct the statistical analysis smoothly. Therefore, we employ value added to capture the demand side of the economy. For the statistical processing relationship between value added and final demand, see the JIP database 2014 website of RIETI.

It should be noted that the original data for value added generates outliers in these indices for 1982 and 1983. This is because electronic equipment and electric measuring instruments (no. 50) takes a value in 1982 (64,707,985 million) that may be an outlier. Therefore, we changed this value and plotted it by smoothing its value with the 5-year average.

Although we do not report the detail because of limit of space, we also calculated structural change index for output for each sector. It is sector M2 (export-core manufacturing sector) that presented the most rapid structural change after the 1990s. In addition, the standard deviation of this sector also recorded the highest value. Therefore, the acceleration and fluctuation of structural change in output since the 1990s are especially led by the export-core manufacturing sector. In fact, this sector plays an important role for shaping the growth process since the 1990s, as we will see in the Harberger’s diagram.

The log variance measures the degree of inequality in economic outcomes. It also has an advantage in that we can understand the source of change in inequality by decomposing it into within-group effects (effect of dispersion within each group) and between-group effects (effect of dispersion between different groups). A rise in this variable means that the dispersion is increasing, and a fall means it is decreasing.

These plots are modified illustrations of Harberger (1998). With regard to labour-productivity decomposition, the current method follows (Syrquin 1998). Since the aggregate labour productivity per man-hour y is defined by \(y=\sum y_i s_{L,i}\), where \(y_i\) is the sectoral labour productivity per man-hour and \(s_{L,i}\) the sectoral share of man-hours, the increment of labour productivity is as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \Delta y=\sum _i \Delta y_i s_{L,i} +\sum _i y_i \Delta s_{L,i} \end{aligned}$$The growth rate of labour productivity at the macroeconomic level is obtained by dividing both sides by y, which is

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{\Delta y}{y}=\sum _i s_{L,i}\left( \frac{\Delta y_i}{y} +\frac{\Delta s_{L,i}}{s_{L}}\cdot \frac{y_i}{y} \right) \end{aligned}$$where the first term in parenthesis represents the ‘within effect’ and the second term represents the ‘between effect’ (Baily et al. 1992; Krüger 2008b). Therefore, the aggregate productivity growth can be decomposed into within-sector growth in labour productivity and sectoral shift in man-hour share.

In his original TFP analysis, Harberger (1998) explained the relationship between the distribution of sectoral performance and macroeconomic outcome as ‘yeast versus mushrooms’. This is a metaphor used for the economic growth process, in which the ‘yeast’ process refers to each industrial sector evenly and mostly contributing to TFP growth, whereas the ‘mushrooms’ process indicates the TFP growth process in which only a small share of industry contributes intensively. Inklaar and Timmer (2007) and Timmer et al. (2013) are applications of this metaphor for industry pattern of growth.

Although we do not report the detail due to space limitation, we also check the possibility of multi-collinearity in the estimated equations by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) among the explanatory variables. Generally, if the value of VIF exceeds 10, there is multi-collinearity among the variables. The result is that none of VIF exceeds 10. Therefore, there is no multi-collinearity of different SCIs in the estimated equations.

References

Ansari M, Mussida C, Pastore F (2013) Note on Lilien and modified Lilien index. IZA discussion paper (7198), pp 1–9

Baily M, Hulten C, Campbell D (1992) Productivity dynamics in manufacturing plants. In: Microeconomics, brookings papers on economic activity, pp 187–267

Baumol W (1967) Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis. Am Econ Rev 57(3):415–426

Baumol W, Blackman S, Wolff E (1985) Unbalanced growth revisited: asymptotic stagnancy and new evidence. Am Econ Rev 75(4):806–817

Boyer R, Uemura H, Isogai A (eds) (2011) Diversity and transformations of Asian capitalisms: a de Facto regional integration. Routledge, London

Boyer R, Yamada T (eds) (2000) Japanese capitalism in crisis: a régulationist interpretation. Routledge, London

Chenery H, Srinivasan T (eds) (1988) Handbook of development economics, vol 1. North Holland, Amsterdam

Dietrich A (2012) Does growth cause structural change, or is it the other way around? A dynamic panel data analysis for seven OECD countries. Empir Econ 43(3):915–944

Franke R, Kalmbach P (2005) Structural change in the manufacturing sector and its impact on business-related services: an input–output study for Germany. Struct Change Econ Dyn 16(4):467–488

Fukao K (2012) Lost two decades and Japanese economy. Nihonkeiazi Shinbunsha, Tokyo (in Japanese)

Fukao K, Miyagawa T (eds) (2008) Productivity and Japanese economic growth: empirical analysis at industrial and firm level using JIP database. Tokyo University Press, Tokyo (in Japanese)

Harberger A (1998) A vision of the growth process. Am Econ Rev 88(1):1–32

Hartwig J (2011) Testing the Baumol–Nordhaus model with EU KLEMS data. Rev Income Wealth 57(3):471–489

Hartwig J (2012) Testing the growth effects of structural change. Struct Change Econ Dyn 23(1):11–24

Hein E (2014) Distribution and growth after Keynes. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Inklaar R, Timmer M (2007) Of yeast and mushrooms: patterns of industry-level productivity growth. German Econ Rev 8(2):174–187

Ito K, Lechevalier S (2009) The evolution of the productivity dispersion of firms: a reevaluation of its determinants in the case of Japan. Rev World Econ 145(3):405–429

Krüger J (2008a) Productivity and structural change: a review of the literature. J Econ Surv 22(2):330–363

Krüge K (2008b) The sources of aggregate productivity growth: US manufacturing industries, 1958–1996. Bull Econ Res 60(4):405–427

Lavoie M, Stockhammer E (eds) (2013) Wage-led growth: an equitable strategy for economic recovery. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Lilien D (1982) Sectoral shifts and cyclical unemployment. J Polit Econ 90(4):777–793

Morikawa M (2014) Productivity analysis in service industries: an empirical analysis using microdata. Nihon Hyoronsha, Tokyo (in Japanese)

Nordhaus W (2008) Baumol’s diseases: a macroeconomics perspective. B.E. J Macroecon 8(1):1–37

Pasinetti L (1993) Structural economic dynamics: a theory of the economic consequences of human learning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Peneder M (2003) Industrial structure and aggregate growth. Struct Change Econ Dyn 14(4):427–448

Prasad E (1997) Sectoral shifts and structural change in the Japanese economy: evidence and interpretation. Japan World Econ 9(3):293–313

Rowthorn RE, Wells JR (1987) De-industrialization and foreign trade. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Maroto-Sánchez A, Cuadrado-Roura JR (2009) Is growth of services an obstacle to productivity growth? A comparative analysis. Struct Change Econ Dyn 20(4):254–265

Syrquin M (1988) Patterns of structural change. Chenery and Srinivasan, pp 203–273

Timmer M, Inklaar R, O’Mahony M, van Ark B (eds) (2013) Economic growth in Europe: a comparative industry perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Uemura H, Tahara S (2014) The transformation of growth regime and de-industrialization in Japan. Revue de la Régulation 15(1)

Yoshikawa H (2003) Role of demand in macroeconomics. Jap Econ Rev 54(1):1–27

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I thank participants at International Conference Research & Régulation, Keynesian society, post-Keynesian society, and Japan society of political economy in 2015 and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. This work was supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 25380225.

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix, we report the unit root test results of the panel data analysis in Sect. 4. We conducted four types of panel unit root tests. The LLC and Breitung tests are used for common unit roots in panel data, and the IPS and Fisher-type ADF tests are used for individual unit roots panel data. Each test includes an individual intercept and trend in test equation. The lag length in these tests is selected by automatic lag length selection based on the Schwarz information criterion.

Table 7 shows the test statistics and unit root test results in level by the periods to be examined (i.e. 1973–2011, 1974–1991, and 1991–2011). Almost all tests for the variables from 1973 to 2011 reject the null hypothesis of both common and individual unit root processes at the 1 % significance level. The Breitung test for \(MLI_{LBR}\), \(MLI_{KPT}\), \(NAV_{LBR}\), and \(NAV_{KPT}\) from 1974 to 1991 cannot reject the common unit root process at the 10 % significance level, whereas the other three tests for these variables reject the unit root process at the 1 % significance level. The Breitung test for \(MLI_{KPT}\), \(MLI_{KL}\), \(NAV_{KPT}\), and \(NAV_{KL}\) from 1991 to 2011 cannot reject the common unit root process at the 10 % significance level. The IPS test for \(MLI_{KPT}\) from 1991 to 2011 also cannot reject the unit root process at the 10 % significance level, but the LLC and ADF tests for \(MLI_{KPT}\) from 1991 to 2011 reject the unit root process at the 5 and 10 % significance levels, respectively.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishi, H. Structural change and transformation of growth regime in the Japanese economy. Evolut Inst Econ Rev 13, 183–215 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-016-0034-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-016-0034-5