Abstract

In this paper, we explore with a model the potential tensions between the incentive system of groups of inventors and knowledge diversity in a high tech firm. We show that, when all groups are rewarded and able to interact freely with their peers, extrinsic and intrinsic motives are mutually self-reinforcing, leading to crowding in effects. As a result, the level of created knowledge increases in each group, reinforcing the diversity of the firm’s knowledge base. By contrast, competitive rewards and constrained autonomy are likely to produce motivating effects in a small number of groups, limiting knowledge creation to the firm’s core competencies. In this case, the firm can suffer from crowding out effects by the other groups, leading eventually to the extinction of creation in their fields and reduced diversity in the long run. The results are illustrated with empirical findings from a case study of a French high tech firm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The policy was criticized by some business units on the basis of social network effects. In particular, there was a suspicion that engineers trained in the same French engineering schools as committee members were being favored.

Engineers in the past had been recruited on the basis of known networks, including the Ecole Polytechnique (France’s most prestigious engineering school). Engineers who had graduated from the Ecole Polytechnique shared a set of values based on history, myth and technical culture, and used a common language (Kessler 2005). The new intake challenged the validity of these competencies and questioned their content.

Patent applications increased by 50 % since 2008 with an average number of new inventions by researchers increasing from 350 in 2008, 359 in 2009 to 364 in 2010. The quality of these applications was also improved, with a significant growth in the number of patents with direct commercial application (See Ayerbe et al. 2012).

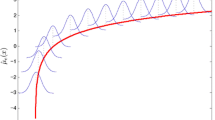

We assume that − w ≤ b ≤ w, which implies that extrinsic motivation is non negative. In contrast, intrinsic motivation can be negative, leading to crowding out effects.

References

Amabile TM, Conti R, Coon H, Lazenby J, Herron M (1996) Assessing the Work Environment for Creativity. Acad Manag J 39(5):1154–1184

Amabile TM (1997) Motivating creativity in organizations: on doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif Manag Rev 40:39–58

Amabile T (1998) How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review. Sept 77–87

Amabile TM, Goldfarb P, Brackfield SC (1990) Social influences on creativity: evaluation, coaction, and surveillance. Creat Res J 3:6–21

Ancona DG, Caldwell DF (1992) Bridging the boundary: external activity and performance in organizational teams. Admin Sci Q 37:634–665

Appelyard MM, Brown C, Sattler L (2006) An international investigation of problem solving performance in the semi conductor industry. J Product Innov Manag 23(2):147–167

Appold SJ (2001) Is meritocracy outmoded in a knowledge-based economy? Singap Econ Rev 46(1):17–49

Ayerbe C, Lazaric N, Callois M, Mitkova L (2012) Nouveaux enjeux d’organisation de la propriété industrielle dans les industries complexes: une discussion à partir du cas Thales. Revue d’économie Industrielle, pp 9–41

Audia PG, Goncalo JA (2007) Success and creativity over time: a study of inventors in the hard-disk drive industry. Manag Sci 53:1–15

Badawy MK (1973) The myth of the professional employee. Pers J 52(41):45

Bessen J, Maskin E (2009) Sequential innovation, patents, and imitation. RAND J Econ 40(4):611–635

Cohendet P, Llerena P (2003) Routines and communities in the theory of the firm. Ind Corp Chang 12:271–297

Deci EL, Ryan RM (1985) Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press, New York

Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM (1999) A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol Bull 125:627–668

Deci EL (2008) A self determination theory view of rewards, motivation and organizations. Working paper Inapor projet 08/02

Dupouët O, Yildizoglu M (2006) Organizational performance in hierarchies and communities of practice. J Econ Behav Organ 61:668–690

Fehr E, Falk A (2002) Psychological foundations of incentives. Eur Econ Rev 4–5:687–724

Festré A, Garrouste P (2007) Self-determination and incentives: a new look at the crowding out effect. Working paper Inapor project

Foss N, Heimeriks K, Winter S, Zollo M (2012) A Hegelian dialogue on the microfoundations of organizational routines and capabilities. Eur Manag Rev 9:173–197

Friebel G, Giannetti M (2009) Fighting for talent: risk-taking, corporate volatility and organisation change. Econ J 119(540):1344–1373

Frey K, Lüthje C, Haag S (2011) Whom should firms attract to open innovation platforms? the role of knowledge diversity and motivation. Long Range Plan 44:397–420

Gagné M, Forest J (2008) The study of compensation systems through the lens of self-determination theory: Reconciling 35 years of debate. Can Psychol/Psychologie canadienne 49:225–232

Gottschalg O, Zollo M (2007) Interest alignment and competitive advantage. Acad Manag Rev 32:418–437

Grandori A (2001) Neither hierarchy nor identity: knowledge-governance mechanisms and the theory of the firm. J Manag Governance 5:381–399

Hackman JR (1987) The design of work teams. In: Lorsch J (ed)Handbook of organizational behavior, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, pp 315–342

Hackman JR, Oldham GR (1976) Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ Behav Hum Perform 16:250–279

Hauser JR (1998) Research, development, and Engineering metric s. Manag sci 44(12):1670–1689

Hoegl M, Parboteeah KP (2006) Autonomy and teamwork in innovative projects. Hum Resour Manag 45(1):67–79

Hoegl M, Weinkauf K, Gemuenden HG (2004) Interteam coordination Project commitment, and team work in multiteam R and D projects: a longitudinal study. Organ Sci 15(1):38–55

Kehr HM (2004) Integrating implicit motives, explicit motives, and perceived abilities: the compensatory model of work motivation and volition. Acad Manag Rev 29:479–499

Kessler C (2005) L’esprit de corps dans les grands corps de l’Etat en France. Working Paper CERSA, University of Paris

Lakhani KR, Von Hippel E (2003) How open source works: free user-to-user assistance. Res Policy 32(6):323–343

Lazaric N (2011) Organizational routines and cognition: an introduction to empirical and analytical contributions. J Inst Econ 7(2):147–46

Lazaric N, Raybaut A (2005) Knowledge, hierarchy and the selection of routines: an interpretative model with group interactions. J Evol Econ 15:393–421

Lazaric N, Raybaut A (2007) Knowledge, hierarchy and incentives: Why human resource policy and trust matter. Int J Technol Glob 3:8–23

Lindenberg S, Foss NJ (2011) Managing joint production motivation: the role of goal framing and governance mechanisms. Acad Manag Rev 36:500–525

Marengo L (1992) Coordination and organizational learning in the firm. J Evol Econ 4:313–26

Minkler L (2004) Shirking and motivations in firms: survey evidence on worker attitudes. Int J Ind Organ 22:863–884

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23(2):242–266

Nooteboom B (2000) Learning by interaction: absorptive capacity, cognitive distance and governance. J Manag Governance 4:69–92

O’Leary MB, Mortensen M (2010) Go(con) figure: subgroups, imbalance, and isolates in geographically dispersed teams. Organization Science 21:115–31

Osterloh M, Frey B (2000) Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational firms. Organ Sci 11:538–550

Owan H, Nagaoka S (2011) Intrinsic and Extrinsic motivations of inventors. RIETI Discussion paper series 11- E- 022

Pelled LH, Eisenhardt KM, Xin KR (1999) Exploring the black box: an analysis of work, group diversity and performance. Admin Sci Q 44:1–28

Sarin S, Mahajan V (2001) The effect of rewards structures on the performance of cross-functional product development teams. J Mark65(2):35–53

Sauermann H (2008) Individual incentives as drivers of innovative process and performance. Phd dissertation, Graduate School of Duke University

Sauermann H, Cohen W (2010) What makes them tick? - employee motives and firm innovation. Manag Sci 56(12):2134–2153

Siemsen E, Balasubramanian S, Roth AV (2007) Incentives that induce task-related effort, helping, and knowledge sharing in workgroups. Manag Sci 53:1533–1550

Smith K, Collins C, Clark KD (2005) Existing Knowledge, Knowledge creation capability, and the rate of the new products introduction in high technology firms. Acad Manag J 48(2):346–356

Som A (2009) Innovation and R and D in the global environment: the case of group Thales. Int J Bus Innov Res 3(3):268–280

Stephan PE, Levin SG (1992) Striking the Mother Lode in science. Oxford University Press

Wageman R (1995) Interdependence and group, effectiveness. Admin Sci Q 40:145–180

West MA (2002) Sparkling Fountains or stagnant Pond : an integrative model of creativity and innovation implementation in work groups. Appl Psychol: Int Rev 51(3):355–424

Weingart LR, Todorova G, Cronin MA (2010) Task Conflict, Problem solving and yielding: effects on team cognition and performance in functionally diverse innovation Teams. Negot Conflict Manag Res 3:312–337

Winter SG (2012) Capabilities: their origins and ancestry. J Manag Stud 49(8):1402–1406

Witt U (2011) Emergence and functionality of organizational routines: An individualistic approach. J Inst Econ 7(2):157–174

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lazaric, N., Raybaut, A. Do incentive systems spur work motivation of inventors in high tech firms? A group-based perspective. J Evol Econ 24, 135–157 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-013-0336-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-013-0336-2