Abstract

Global economic crises can have a significant impact on businesses across different sectors, often leading to difficulties or even insolvency. In such a situation, organizational resilience is often considered a means to ensure the competitive advantage. Although the concept has gained popularity in recent years, empirical research on the determinants and effects of organizational resilience remains scarce. Therefore, we first examine the potential management accounting determinants of organizational resilience. Second, we investigate the effect of organizational resilience on competitive advantage. A cross-sectional survey conducted in January and February 2021 resulted in 127 observations of medium- and large-sized German companies. We find that a risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function of budgeting are positively associated with both the adaptive capability factor and the planning factor of organizational resilience. Furthermore, we find that adaptive capability increases a company’s competitive advantage in both business-as-usual situations and in times of crisis. Our findings inform practitioners about how key management accounting concepts, such as risk management and corporate planning, can increase organizational resilience and, consequently, the positive outcomes of organizational resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

At present, different global crises have a significant impact on the global economy. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a 3.4% decline in global real GDP in 2020 (Statista, 2022), affecting companies across various sectors (Verma & Gustafsson, 2020). Russia’s aggression against Ukraine further strained the economy with sanctions and increased commodity prices (United Nations, 2022). The looming global climate crisis threatens societal norms and requires immediate global action to address climate change (Lee et al., 2023), which is already evident through disasters such as floods and forest fires.

The concept of organizational resilience has received considerable attention in the current context of multiple global crises. Organizational resilience is a meta-capability that enables companies not only to manage crises effectively but also to thrive despite disruptions and challenging business environments (Duchek, 2020; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). It enables companies to anticipate, cope with, and adapt to unexpected events, thus creating and sustaining competitive advantages (Hilmann & Guenther, 2021). Therefore, resilience is an important concept that needs to be explored in greater detail, given the many challenges faced by companies, not only due to acute crises but also due to the disruptive pressures of digital and sustainable transformation. Although organizational resilience has been extensively defined and discussed (e.g., Duchek, 2020; Linnenluecke, 2017; Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003), evidence on both the determinants and consequences of organizational resilience remains limited (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2021). Hence, both practitioners and academics are keen to explore how companies can enhance organizational resilience through key management accounting concepts, such as risk management and corporate planning, ultimately leading to sustained competitive advantages.

Against this backdrop, this study examines two potential factors that influence organizational resilience from a management accounting perspective. In addition, we explore the impact of organizational resilience on a company’s competitive advantage during a crisis. Therefore, our research objectives are twofold. First, we seek to identify factors that contribute to organizational resilience from a management accounting perspective. Second, we assess organizational resilience’s potential advantages by examining its effects on competitive advantage in times of crisis.

To analyze organizational resilience, we focus on two established factors identified by Whitman et al. (2013): planning and adaptive capability. The planning factor emphasizes the anticipation of crises and emergencies and the importance of preparedness for such events. Conversely, the adaptive capability factor pertains to the organizational culture and mindset that promotes a proactive approach to dealing with change and challenges. It highlights the significance of teamwork, problem-solving orientation, innovative thinking, and ensuring the availability of information and resources to address unexpected problems. Together, these factors offer a holistic view of resilience, combining strategic preparedness with the ability to respond effectively when faced with disruptions.

We investigate key management accounting concepts related to identifying risks, managing uncertainty, and planning a company’s future to explore the potential determinants of organizational resilience. More specifically, as possible factors influencing organizational resilience, we examine a company’s risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function of budgeting. Thus, we investigate factors that capture the relevance a company places on a holistic risk management approach and on the planning function of budgeting.

Risk management is often recognized as a crucial aspect of management accounting (Bhimani, 2009; Braumann, 2018; Soin & Collier, 2013). It assists companies in considering both risks and opportunities when determining their strategies (Beasley et al., 2006; Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission [COSO], 2004, 2017). However, some ambiguity remains regarding the implications of integrated risk management, particularly in relation to resilience (Anton & Nucu, 2020; Aven, 2016). The updated COSO framework for enterprise risk management (ERM) highlights that an integrated and holistic approach to risk management can enhance organizational resilience. This is because ERM enables companies to identify significant risks and build the necessary capabilities to swiftly respond to those risks (COSO, 2017). Therefore, we expect that a more pronounced risk management orientation will contribute to increased organizational resilience (McManus et al., 2008; Ponomarov, 2012).

Corporate planning is another crucial area of management accounting (Anthony & Govindarajan, 2007; Bhimani et al., 2019). In this regard, we examine the importance of the planning function of budgeting as a second determinant of organizational resilience. The planning function of budgeting refers to the use of short-term budgets for coordination, resource allocation, alignment with the company’s objectives, and delegation of decision-making and spending authority. This function can be distinguished from the control and evaluation functions of budgeting (Bergmann et al., 2020). Thus, companies primarily focusing on the planning function may place less importance on other budgeting functions.Footnote 1 Becker et al. (2016) show that the importance of the planning function increases when a company is significantly more impacted by an economic crisis. Consequently, focusing on the planning function may prove beneficial in addressing uncertainty, particularly during crises. Specifically, we argue that a greater emphasis on the planning function is indicative of a specific mindset that enables companies to better anticipate crises and develop the necessary capabilities to cope with them. Therefore, we expect a positive association between the importance of the planning function of budgeting and both factors of organizational resilience.

With regard to possible consequences, organizational resilience is not merely developed as an end in itself but rather as a means to enable companies to respond to unexpected situations, disruptions, and external pressures. Companies that invest in building resilience anticipate gaining an advantage when faced with unexpected events and changes. Therefore, we argue that both factors of resilience have a positive impact on a company’s competitive advantage during times of crisis.

To test our hypotheses, we used cross-sectional survey data obtained from medium-sized and large German companies during January and February 2021. Our dataset consists of 127 responses provided by the representatives of these companies. Using covariance-based structural equation modeling, we find statistical evidence to support our predictions. Specifically, we show that a risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function are positively associated with both the adaptive capability factor and the planning factor of organizational resilience. Additionally, our analysis reveals that organizational resilience positively impacts a company’s competitive advantage during times of crisis, specifically in terms of the adaptive capability factor. These empirical findings underscore that a certain perspective on key management accounting systems, i.e., a risk management orientation and a focus on the planning function of budgeting, can positively influence organizational resilience and enhance a company’s competitive advantage.

Our study makes valuable contributions to both theory and practice. From a theoretical perspective, we contribute to the growing research on organizational resilience (Baird et al., 2023; Bracci & Tallaki, 2021; Duchek, 2020; Hillmann, 2020; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021). Specifically, we examine how key management accounting concepts, namely risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function of budgeting, can impact organizational resilience, adding to the literature on the subject (Barbera et al., 2020). In addition, our study contributes to the literature on management control systems during economic crises; however, rather than directly exploring the relationship between management control systems and crisis impact (Becker et al., 2016; Colignon & Covaleski, 1988; Collins et al., 1997), we focus on the role of organizational resilience as an additional mediating factor.

From a practical perspective, our study identifies factors that influence organizational resilience that can be actively shaped by decision makers. We find that a risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function of budgeting are positively associated with organizational resilience, highlighting the benefits of comprehensive risk management that may not be readily apparent (Baxter et al., 2013). Furthermore, our findings provide valuable insights for practitioners by emphasizing the positive impact of organizational resilience on a company’s competitive advantage in times of crisis. Given the intangible nature of resilience and its difficult monetization, we stress the relevance of organizational resilience and its link to competitiveness, as it often receives less attention in monetarily oriented companies (Lee et al., 2013; Stephenson et al., 2010).

The paper proceeds as follows: Sect. 2 provides an overview of organizational resilience and develops hypotheses. Section 3 describes the design and methodology of our study, and Sect. 4 presents the empirical results. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes and discusses the limitations and directions for future research.

2 Background and hypothesis development

2.1 Organizational resilience

Organizational resilience is a meta-capability that enables companies “to cope effectively with unexpected events, bounce back from crises, and even foster future success” (Duchek, 2020, p. 215). This capability allows companies to survive and overcome existential threats to their continued existence (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). While other similar capabilities, such as agility, robustness, and flexibility, are more common, they do not possess the same comprehensive scope as resilience. To differentiate resilience from these concepts, Duchek (2020) highlights two key aspects. First, resilience is focused on addressing unexpected events rather than providing solutions to day-to-day business challenges (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). Second, resilience encompasses the possibility of adaptation, enabling companies to emerge stronger from a crisis (Madni & Jackson, 2009).

Resilience is a multifaceted and complex construct that should not be seen as a mere outcome in terms of recovery ability, but as a capability that drives resilient outcomes across all phases of a crisis (Duchek et al., 2020; Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2011; Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003). Related to the phases of a crisis, there are three successive resilience stages: anticipation, coping, and adaptation (Duchek et al., 2020), in which certain capabilities together form the meta-capability resilience. In the anticipation stage, which occurs before a crisis, companies need anticipatory capabilities to detect critical developments in advance and respond accordingly. These capabilities also enhance situation awareness and sensemaking within the organization (Barbera et al., 2017). However, simply acting with foresight does not guarantee the avoidance of crises (Duchek et al., 2020). In the coping stage, companies require activities that enable an appropriate and tailored response during a crisis to ensure the company’s survival (Barbera et al., 2017). Finally, in the adaptation stage following a crisis, resilience allows organizations to recover, seize opportunities, and become stronger. Thus, resilient companies may use external shocks as catalysts for improvement and the development of new capabilities (Duchek, 2020; Lee et al., 2013).

Considering these stages, the concept of organizational resilience also shares some important aspects with the concept of dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities are defined as an organization’s ability to build and reconfigure its resource base through organizational learning and to effectively respond to rapidly changing environments by sensing and seizing opportunities (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2007; Pierce et al., 2002; Teece et al., 1997; Zollo & Winter, 2002). There are several similarities between organizational resilience and dynamic capabilities. First, Katkalo et al. (2010) describe dynamic capabilities as “meta-routines” that manipulate existing resource configurations and are often a combination of simpler capabilities in the form of organizational processes (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2007; Ponomarov, 2012). Second, both organizational resilience and dynamic capabilities are relevant not only in times of business-as-usual but also in times of crises or unexpected events (Duchek, 2020; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Zahra & George, 2002). They emphasize the importance of being able to react quickly to emerging conditions and the creation of situation-specific knowledge to learn from (Duchek, 2020; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Lee et al., 2013). Third, both concepts promote a dynamic view of the organization, emphasizing the continuous renewal of competences and resources and the ability to adapt to changing market conditions (Duchek, 2020; Ponomarov, 2012; Teece et al., 1997; Zahra & George, 2002). Therefore, resilience can be seen as a particular dynamic capability that focuses specifically on building the capabilities necessary to detect unexpected events and respond appropriately, enabling organizations to address risks and capitalize on emerging opportunities.

Although the relevance of organizational resilience has been widely acknowledged, many companies fail to recognize its importance and do not invest enough in the development of this capability (Lee et al., 2013). Against this backdrop, several studies have focused on developing a measurement tool for organizational resilience such that organizations can assess their resilience capabilities (e.g., Lee et al., 2013; Mallak, 1998; McManus et al., 2008; Somers, 2009; Stephenson, 2010). In this respect, Lee et al. (2013) identified and validated two factors of organizational resilience: planning and adaptive capability.Footnote 2 These two factors capture the behavioral and social aspects of organizational resilience. Specifically, the planning factor of resilience recognizes the potential occurrence of crises and involves the development of explicit strategies and measures for an effective crisis response. This includes creating emergency plans, conducting crisis simulations, and establishing recovery priorities (Stephenson, 2010). Conversely, the adaptive capability factor of resilience is closely tied to the company’s values and mindsets. It reflects the organization’s ability to adapt and respond effectively to unexpected challenges by fostering collaboration, empowering employees, maintaining knowledge resources, promoting innovative thinking, and making swift and informed decisions (Stephenson, 2010).

Although these two perspectives on resilience provide valuable insights into the dimensions of resilience, it is essential to explicitly explore the factors that determine organizational resilience. In the following section, we propose hypotheses for potential determinants of resilience from a management accounting perspective and for the potential effects of organizational resilience, i.e., competitive advantages.

With regard to the determinants of resilience, we focus on management accounting concepts that address uncertainty and can be actively influenced by decision makers (Barbera et al., 2020). Specifically, we examine two possible determinants: risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function of budgeting. Therefore, we do not explicitly focus on specific management accounting practices, especially with regard to the planning function of budgeting. Instead, we focus on attitudes toward certain management accounting systems that ultimately lead to the adoption of specific management accounting practices that are consistent with those attitudes. Nevertheless, organizational members actively choose their attitudes toward risk management and budgeting. In this regard, we emphasize the importance of clarifying decision makers’ goals and attitudes regarding management accounting systems such as risk management and budgeting. This step should, moreover, precede the selection of specific practices. Hence, our focus on these determinants and their influence on organizational resilience stems from the belief that decision makers should have a clear understanding of their management accounting objectives before implementing particular practices. Establishing these goals in advance helps align practices with broader organizational objectives.

2.2 Determinants of organizational resilience

2.2.1 Risk management orientation

Risk management is a crucial aspect of management accounting that supports organizations in identifying, evaluating, and managing risks at the enterprise level (Anton & Nucu, 2020; Braumann, 2018; COSO, 2017). It involves coordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to risk (ISO, 2018). Typically, risk management follows a systematic, comprehensive, and structured process with well-established stages that are sequentially undertaken (Hopkin, 2017).

Risk management activities are often consolidated and organized within an ERM framework, which has been associated with improved decision making in both operational and strategic contexts (Hoyt & Liebenberg, 2011). Several authors have highlighted that an effective ERM should encompass both hard, technological components, such as specific risk management tools, and soft components, such as risk management culture (Arena et al., 2010; Bruno-Britz, 2009; Mikes, 2009). In this context, Braumann (2018) explores risk awareness as a cultural component that may not be explicitly documented but should be embedded in employees’ risk thinking. She argues that only individuals who are risk aware can proactively identify risks, contemplate their impact, and share crucial risk information that requires attention. To foster risk awareness, signaling organizational priorities to employees is vital because it provides formal guidance and structure to facilitate effective risk management activities (Malina & Selto, 2001).

Ponomarov (2012) merges these two dimensions of hard and soft components in his concept of risk management orientation, which refers to an organizational culture that prioritizes risk management and establishes behavioral norms regarding organizational development and responsiveness to risk-related market information. More specifically, the concept captures general practices such as establishing continuous risk management processes, determining concrete coping strategies for significant risks, and having a team or an employee responsible for the risk management system. Additionally, the concept acknowledges the importance of establishing a risk-oriented culture. That is, a high degree of risk management orientation is related to an organizational culture that places high value on risk management and encourages risk awareness and mitigation (Ponomarov, 2012).

The COSO framework highlights the positive relationship between a holistic and integrated ERM approach and organizational resilience (COSO, 2017). Hence, we expect that a holistic risk management orientation is probably associated with both factors of organizational resilience. First, a risk management orientation elevates risk awareness beyond traditional financial risks, encompassing various types of risk and unforeseen risks (McManus et al., 2008; Settembre-Blundo et al., 2021). Consequently, when risk awareness in an organization is high, all employees are constantly identifying and, if possible, managing risks (Braumann, 2018; Braumann et al., 2020). Thus, through increased risk awareness, companies can anticipate risks, apply sufficient risk management practices, and plan coordinated and appropriate responses (McManus et al., 2008). This anticipation and preparation in terms of risks closely align with the planning factor of organizational resilience, which refers to the anticipation and preparation of crises. If companies are more risk aware, they are likely more aware of possible crises and extreme events and prepare accordingly.

Hence, we argue that a risk management orientation is positively associated with the planning factor of organizational resilience because a strong risk management orientation enables companies to identify and cope with risks that stem from crises or disruptive events. This prediction is reflected in the following hypothesis:

H1a

Risk management orientation is positively associated with the planning factor of organizational resilience.

However, a risk management orientation not only aids in anticipation but also enhances an organization’s adaptive capabilities. For example, risk management-oriented companies are likely to analyze past stress situations and draw conclusions about general preparedness for crises and disruption. Therefore, learning from past crises enables a more comprehensive crisis preparation (Settembre-Blundo et al., 2021). In addition, high risk awareness creates a mindset among employees to actively identify and address potential problems, which in turn encourages solution-seeking and problem-solving.

Taken together, we expect that a risk management orientation increases a company’s adaptive capabilities, as reflected in the following hypothesis:

H1b

Risk management orientation is positively associated with the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience.

2.2.2 Importance of the planning function of budgeting

Short-term planning, as an integral component of budgeting, plays a crucial role within organizations and is widely recognized as a vital management control system (e.g., Anthony & Govindarajan, 2007; Bhimani et al., 2019; Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017). In general, budgeting encompasses the process of setting targets and creating plans that guide organizational activities (Datar & Rajan, 2021). Extensive research has investigated the various macrofunctions of budgeting, including planning, control, and motivation and performance evaluation (Arnold & Artz, 2019; Becker et al., 2016; Hansen & Van der Stede, 2004; Sivabalan et al., 2009).

The planning function of budgeting refers to the development of action plans and has a significant impact on various aspects, including operational capacities, cost and price determination, and resource allocation (Bergmann et al., 2020; Sivabalan et al., 2009). In close connection to planning, the control function of budgets involves using budgets as a monitoring tool to compare actual financial performance with budgeted targets (Sivabalan et al., 2009). Lastly, the motivation and performance evaluation function of budgeting entails using budgets as targets to drive employee and/or business unit efforts and performance, often with the aim of incentivizing high levels of performance (Arnold & Artz, 2019; Hansen & Van der Stede, 2004).

The planning function of budgeting likely plays a crucial role in fostering organizational resilience. In this regard, Becker et al. (2016) find that the planning and resource allocation functions of budgeting became more significant for companies affected by an economic crisis. This finding indicates that prioritizing the planning function can enhance a company’s ability to respond and navigate through crises successfully. We build on this general notion that the planning function is associated with organizational resilience and argue that the importance of the planning function affects both factors of organizational resilience.

First, concerning the planning factor of organizational resilience, we expect that a company that emphasizes the planning function is more likely to have a deep understanding of its internal and external environment, enabling it to anticipate potential crises (Becker et al., 2016). By gathering detailed information, organizations can identify current and future threats more effectively and develop appropriate emergency plans. Therefore, we predict that the importance of the planning function positively influences the planning factor of organizational resilience.

H2a

The importance of the planning function of budgeting is positively associated with the planning factor of organizational resilience.

Second, we expect that focusing on the planning function of budgeting offers the potential for building organizational resilience in terms of adaptive capabilities. For example, one central aspect of the planning function of budgeting is the equipment of employees with decision-making powers. If decision-making authorities are effectively distributed, the company should be able to make quick decisions in times of crisis and disruption. Another important aspect of the planning function is resource allocation. Especially in times of crisis, slack resources are essential for responding and adapting to rapidly changing circumstances (Bourgeois, 1981; Cyert et al., 1963). Comprehensive planning with a focus on resource allocation allows companies to identify and allocate appropriate levels of organizational slack. Finally, as discussed above, companies that emphasize the planning function should have a deep understanding of their internal structures and issues such that managers and employees pay attention to possible problems and their solutions. This could lead to a problem-solving mentality that also serves during times of crisis and disruption. Taken together, we expect that the importance of the planning function of budgeting is related to the build-up of organizational resilience with regard to adaptive capabilities.

H2b

The importance of the planning function of budgeting is positively associated with the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience.

2.3 Effect of organizational resilience on competitive advantage in times of crisis

After having discussed two possible determinants of organizational resilience, we explore in this section whether building organizational resilience can lead to superior firm performance, particularly in times of crisis. This is important against the background that organizations often face challenges in prioritizing resilience initiatives due to competition with other projects for limited resources. To justify the investment in resilience, organizations must be able to evaluate its effectiveness and demonstrate a business case (Lee et al., 2013).

Assessing the impact of resilience on firm performance is complex for several reasons. First, resilience is a multifaceted construct that involves both tangible and intangible dimensions (Duchek, 2020). Second, a challenge in evaluating the effectiveness of resilience lies in the lack of recognition of preventive measures. It is difficult to assign a tangible value to the positive outcomes of resilience, especially those that involve preventing companies from experiencing severe struggles during a crisis. In this context, numerous studies emphasize the importance of understanding the need for and strategies behind investing in resilience. These studies also stress the importance of empirically exploring methodologies to measure the returns on such investments, specifically by analyzing value-based outcomes of resilience (Lee et al., 2013; Ponomarov, 2012).

One approach to evaluating the impact of resilience on performance is to examine competitive advantage, which refers to the relative value creation compared to competitors (Barney, 1991; Helfat et al., 2007). The concept of competitive advantage originates from Porter (1985), who focuses on the analysis of industry structure and two generic strategies: cost leadership and differentiation. Barney (1991) extends this perspective by incorporating a resource-based view that leverages internal strengths to achieve and sustain competitive advantage. The resource-based view is closely associated with the dynamic capability view, which emphasizes the effective manipulation and combination of existing resource configurations. Among the most influential works exploring the link between dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage is Teece’s study (2007), which argues that dynamic capabilities serve “as foundation of enterprise level competitive advantage in regimes of rapid (technological) change” (p. 1341). Katkalo et al. (2010) contribute to this discussion by highlighting how dynamic capabilities enable organizations to orchestrate their resources and competencies to enhance profitability. However, dynamic capabilities alone are not a source of competitive advantage; they are a necessary but not sufficient condition for achieving it (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Helfat et al., 2007; Katkalo et al., 2010). Zahra and George (2002) propose a connection between dynamic capability properties and absorptive capacity, emphasizing the complementary roles of potential and realized absorptive capacity in creating and sustaining competitive advantage. This framework can also be applied to organizational resilience. Anticipation, coping, and adaptation constitute complementary components that work together to establish and maintain competitive advantage. Anticipation is crucial for identifying potential developments and aligning resources to achieve a competitive advantage. Coping enables organizations to capitalize on their advantage when competitors struggle during times of crisis, while adaptation helps sustain the advantage during normal business operations.

The relationship between resilience and competitive advantage has been emphasized in several studies. Parsons (2007) argues that resilience can provide organizations with competitive advantage, while Hamel and Välikangas (2003) posit that resilience itself serves as a distinct source of competitive advantage. Lee et al. (2013) also acknowledge the connection between resilient and competitive companies. Hillmann and Guenther (2021) and Marwa and Milner (2013) find that organizational resilience can indeed be a source of competitive advantage during both business-as-usual and crises. Companies with high situation awareness and adaptive capabilities can respond more effectively to crises, extreme situations, and changes in the market environment. As a result, resilient companies can adapt faster than their competitors. In addition, He et al. (2023) find that resilient companies outperform their competitors in terms of profitability, return on investment, and sales growth.

On the basis of these general considerations regarding organizational resilience and competitive advantages, we argue that both the planning and adaptive capability factors of resilience are associated with competitive advantages during a crisis. As explained earlier, the planning factor of organizational resilience is related to preparedness for crises and disruptions. Specifically, it acknowledges the necessity to practice and test emergency plans, the ability to rapidly shift to a crisis mode, and awareness of the risk of potential crises (Whitman et al., 2013). Hence, the planning aspect of resilience is closely related to companies’ ability to anticipate and cope with crises. Because of this preparedness, resilient companies are more likely to survive crises and disruptions and are less negatively affected than their competitors. Consequently, as captured in the following hypothesis, we expect a positive association between the planning factor of resilience and a company’s competitive advantage during times of crisis:

H3a

The planning factor of organizational resilience is positively associated with a competitive advantage in times of crisis.

However, Reeves and Deimler (2009) argue that only surviving a crisis alone is insufficient; the ability to adapt during crises leads to sustainable competitive advantages. This perspective is captured by the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience, which promotes a certain mindset that is oriented toward problem-solving, agility, and creativity (Whitman et al., 2013). We argue that this mindset enables companies not only to quickly respond to crises and disruption and find solutions to crises-related problems, but also to learn from changing circumstances and adapt business practices that sustainably improve the companies’ situations. Hence, we expect that the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience can contribute to securing and even expanding a competitive advantage during crises, as reflected in the following hypothesis:

H3b

The adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience is positively associated with a competitive advantage in times of crisis.

The hypothesized research model is summarized in Fig. 1.

3 Research method

3.1 Sample description

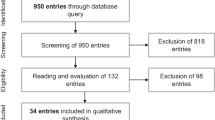

To collect data for our empirical analysis, we conducted a survey among German companies over a six-week period from January to February 2021. We used the Dafne database from Bureau van Dijk for sampling. Our selection criteria included firm solvency, annual revenue of at least €50 million, and the latest account date between 2017 and 2020. We identified 11,319 companies meeting these criteria. From this population, we randomly selected 2,000 companies and distributed paper-based questionnaires via postal mail. Respondents were given the option to return the completed questionnaires via postal mail, email, or fax or to provide their answers online using the Unipark platform. In total, we received 135 questionnaires, representing a response rate of 6.75%. Of the 135 responses, 127 questionnaires met the necessary criteria for inclusion in the analysis, i.e., providing sufficient answers to the items of interest. Thus, our final sample size is 127 (response rate of 6.35%). Overall, the data quality was considered good, with only minor losses due to poor response quality.

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the sample. The respondents mainly consisted of directors (44.88%) and employees (24.41%) from management accounting/”Controlling” departments, indicating a solid understanding of risk management and the planning process within their respective companies. Additionally, the average work experience within the current firm was 12.11 years (not tabulated), demonstrating substantial familiarity with the departments and the overall organization. Regarding company characteristics, about half of the firms (49.61%) reported a total annual revenue between €50 and €149 million. Additionally, 17.32% declared a total annual revenue between €150 and €249 million, while 24.41% stated a total annual revenue between €250 and €999 million. This distribution reflects the diversity of the German economy and many other countries’ economies, with a significant representation of medium-sized companies (Ayyagari et al., 2007; Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs & Climate Action, 2023). Our sample encompasses firms operating in various industries, with product manufacturers (11.81%) and utilities/servicing/disposal (11.02%) being the most common sectors. This diverse industry distribution further enhances the generalizability of our findings.

To examine the possibility of non-response bias in our data, we compared the responses of early and late respondents to constructs of interest. Drawing from the concept proposed by Armstrong and Overton (1977), we assumed that the populations of late respondents and non-respondents would exhibit structural similarity. Hence, we compared the answers in the first 20 questionnaires against those in the last 20 questionnaires we received with regard to our variables of interest. More precisely, we test for significant differences in all variables and items included in our model by deploying Chi square tests for the industry variable and Mann–Whitney U-tests for all remaining variables. On the basis of these tests, we did not identify significant differences between the first and last responders, leading us to conclude that the likelihood of a potential non-response bias impacting our results is minimal.

We acknowledge the potential presence of common-method bias because we employed the same data collection method for both exogenous and endogenous variables (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To address and evaluate this bias in our survey, we followed the recommendations outlined by Podsakoff et al. (2003). First, we carefully designed our questionnaire, specifically framing the study as an examination of “planning in times of COVID-19.” This approach allowed us to cover our focus on organizational resilience and its connection to the other variables under investigation. Moreover, we assured the participants that their personal information would be treated confidentially and anonymously. Furthermore, to statistically assess the potential influence of common-method bias, we conducted Harman’s (1976) single factor test. This involved performing an exploratory factor analysis on all items in the constructs. The test resulted in the identification of five factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1. The highest total variance explained by a single factor was 34.35%, which is below the recommended threshold of 50%. Consequently, this finding indicates the absence of significant common-method bias issues in our data.

3.2 Variable measurement

To ensure the quality and validity of our survey, we developed a standardized questionnaire through an extensive literature review on risk management, corporate planning, organizational resilience, and crises. In the development of our questionnaire, we followed Bedford and Speklé (2018) to ensure construct validity. Thus, whenever possible, we used existing scales that had been previously validated and made necessary refinements to align them with the specific objectives of our study. In addition, for certain aspects that required measurement, we created new items and scales tailored to our research context. To validate our survey design, we conducted a pre-test and sought feedback from two academic experts and two practitioners who specialize in the field of management accounting/”Controlling”. Unless otherwise specified, the questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1—”do not agree” to 5—”fully agree”) for respondents to rate their responses. We also provided an option for respondents to select “not specified” if applicable. In some sections of the questionnaire, such as corporate planning and competitive advantage, we asked respondents to provide their answers based on both the period before the crisis (up until the fourth quarter of 2019) and during the crisis (starting from the first quarter of 2020). This allowed us to capture the dynamics and changes that occurred because of the crisis.

We performed a factor analysis to validate our constructs and ensure their suitability for our model. The results, including factor loadings, reliability, and validity measures, are presented in Table 2. On the basis of the eigenvalue criterion, all variables in our analysis loaded onto a single factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1, indicating that no rotation was necessary (Hair et al., 2019). To establish convergent validity, we retained items that exhibited factor loadings above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2019). The reliability of the constructs was assessed using both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) (Bedford & Speklé, 2018; Cronbach, 1951; Raykov, 1997). Almost all constructs met the recommended threshold of 0.7 for both Cronbach’s alpha and CR, indicating satisfactory internal consistency (Hair et al., 2019). For the construct that captures the importance of the planning function of budgeting, Cronbach’s alpha is just below the threshold (0.694). Hence, we additionally calculated the average inter-item correlation (0.364, not tabulated), which is above the recommended threshold of 0.3 (Hair et al., 2019). Thus, we conclude that the internal consistency of the construct is also sufficient. Convergent validity was examined using the average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). All constructs surpassed the threshold of 0.5 proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981), indicating adequate convergence among the items and their respective constructs. To ensure discriminant validity, we compared the square roots of the AVE scores with the inter-construct correlations, as shown in Table 3. The square root of the AVE for each construct exceeded the correlation coefficients with other constructs, confirming the presence of discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

To calculate the scores of the variables used in our analysis, we computed the average of the responses for each construct based on the identified items (Posch, 2020). In the following section, we provide a more detailed description of the variables and corresponding items used in our analysis. Please refer to the Appendix for a complete list of the items.

Risk management orientation To measure the risk management orientation of the companies (RISK_MGMT), we used a pre-tested and validated scale from Ponomarov (2012), which has previously been used in the context of resilience. We have slightly adapted the scale to fit the scope of our setting. The scale comprises six items that assess various aspects of a company’s risk management orientation. The items capture the presence of risk monitoring processes, risk management culture, continuance strategies in case of major risks, and organization of risk management activities. Thus, the scale relates to both the softer aspects related to the general risk culture and awareness as well as the more tangible and practical aspects related to the implementation of risk management activities. All items were included in the final variable.

Importance of the planning function To assess the importance of the planning function (FCT_PLAN), we adopted an existing scale from Bergmann et al. (2020). The scale measures the perceived importance of various microfunctions within the planning function. Respondents were asked to rate the importance of the following microfunctions on a scale from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important): coordination, resource allocation, alignment with the company’s objectives, and assignment of decision-making and spending authority.Footnote 3

In the theory section, we explain that we focus on the attitude toward different management accounting concepts that should eventually lead to the adoption of certain practices. While RISK_MGMT acknowledges this perspective by also assessing the implementation of risk management activities, FCT_PLAN solely focuses on an attitude toward budgeting. In this regard, existing budgeting research supports the assumption that the importance of a budgeting function implies its actual use within the budgeting process (Arnold & Artz, 2019; Becker et al., 2016; Hansen & Van der Stede, 2004). Hansen and Van der Stede (2004) laid the foundation for this widely accepted connection by empirically demonstrating that the perceived importance of a macrofunction in budgeting is a significant explanatory factor for the actual performance of that macrofunction. Their research provides evidence that the link between importance and use holds true regardless of the various factors that influence the macrofunctions of budgeting, such as organizational structure, strategy, or the operating environment. Therefore, when highlighting the importance of the planning function in budgeting for organizational resilience, companies that recognize its significance are more likely to incorporate it effectively into their budgeting processes.Footnote 4

Nevertheless, to validate that the importance of the planning function is associated with certain budgeting practices, we assess the relationship between FCT_PLAN and a variety of budgeting practices captured in our questionnaire. First, we consider the types and numbers of key performance indicators (KPIs) planned in the budgeting process as possible outcomes of focusing on the planning function. More precisely, we assume that companies with a high focus on the planning function determine more advanced KPIs and a greater variety of KPIs. Hence, we deploy a simple logistic regression to analyze the association between FCT_PLAN and a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 if the company plans cash flow and rentability measures in their budgeting process, and 0 otherwise. We find a significant and positive association between these variables (β = 0.866, p = 0.009, not tabulated). Furthermore, we determine the variety of planned KPIs in the budgeting process. Hence, we count how many different types of KPIs are planned, i.e., revenue, costs, earnings, cash flow, or rentability. A regression of FCT_PLAN on the number of different KPIs shows a significant and positive association between these variables (β = 0.356, p = 0.006, not tabulated). Thus, companies that focus on the planning function of budgeting include more advanced KPIs in their budgets and determine a greater variety of KPIs, which indicates integrated planning. Moreover, we assume that a strong importance of the planning function is associated with higher levels of commitment to the budget. Hence, we regress FCT_PLAN on two items that assess the binding nature of plans concerning targets and allocated resources. We find that FCT_PLAN is significantly and positively associated with commitment to budgeted targets (β = 0.544, p < 0.001, not tabulated) and budgeted resources (β = 0.747, p < 0.001, not tabulated). Taken together, these analyses show that the importance of the planning function manifests in explicit budgeting practices with regard to planned KPIs and the binding nature of plans.

Organizational resilience To measure organizational resilience, we used a pre-tested and validated scale developed by Whitman et al. (2013). Given the inherent challenges in measuring the complex concept of organizational resilience, adopting a pre-tested scale enhances the reliability and construct validity of our study. The scale developed by Whitman et al. (2013) builds upon prior qualitative assessments of organizational resilience by McManus et al. (2008) conducted in New Zealand. Subsequently, Stephenson (2010) and Lee et al. (2013) further refined and quantitatively tested the scale, resulting in two major factors: planning and adaptive capability. Whitman et al. (2013) condensed and extensively validated this scale using three distinct samples. In our study, we incorporated both factors of organizational resilience. However, we modified the response scale from the original four-point Likert scale to a six-point Likert scale. Thus, we followed the existing scale by using an even number of answer options but adjusted it from four to six options to achieve greater granularity.

The scale for the planning factor of organizational resilience (RES_PLAN) includes five items. These items assess the level of preparedness of firms in anticipating and responding to crises. Specifically, they measure aspects such as understanding the potential impact of a crisis, the ability to react swiftly, the establishment of clear priorities, the development of emergency plans, and the cultivation of meaningful external relationships. However, one item (res_plan1) related to the mindfulness of how a crisis could affect the company was dropped from the final variable measurement because of low factor loading.

The second factor, adaptive capability (RES_ADAPT), comprises eight items. These items focus on capturing a culture of awareness and responsibility for potential problems, using internal resources for informed decision-making, disseminating comprehensive knowledge throughout the organization, promoting teamwork, and implementing an active management style. However, one item (res_adapt8) measuring the maintenance of sufficient resources to absorb unexpected changes, was not included in the final variable because of a low factor loading.

We assume that organizational resilience is a capability that cannot be developed rapidly, especially in times of crisis. Consequently, the factors and items of organizational resilience captured in our questionnaire refer to practices and circumstances that are unlikely to be introduced during the crisis. For example, with regard to the planning factor of organizational resilience, cultivating meaningful relationships or practicing and testing emergency plans require considerable time and effort; therefore, these activities are most likely not carried out while a company is currently coping with a crisis. Similarly, with regard to the adaptive capability factor of resilience, changing a company’s culture with regard to, for example, teamwork, problem-solving, and knowledge-sharing takes a lot of time. Therefore, our measurement of organizational resilience should be relatively stable for the investigated period. As a result, the measurement provides insights into a company’s level of resilience both before and during the crisis. Consequently, we expect our measures of resilience to serve as an antecedent to a company’s competitive advantage both during and before the crisis.

Competitive advantage in times of crisis To assess the competitive advantage of firms during the crisis, we used the variable COMP_ADV_CRISIS, which comprises three items. The respondents were asked to rate their companies’ (1) liquidity situation, (2) earnings situation, and (3) debt ratio compared to their competitors’ situations during the crisis. By capturing relative assessments and comparisons with competitors, we aimed to facilitate a broader comparison across companies of various sizes and industries. This approach aligns with the nature of competitive advantage, allowing us to examine the relative performance of companies during the crisis period (Wang et al., 2022).

Control variables In addition to the main variables, we included five control variables in our model to account for potential confounding effects on both organizational resilience and competitive advantage. First, we considered company size as a potential influencer because larger companies are often assumed to be more resilient (Huang et al., 2020). We operationalized the company size on the basis of annual revenue. However, because we assessed annual revenue ordinally, we cannot include the variable as such in our model. Therefore, we compute dummy variables for each ordinal level of annual revenue and include them in our model (REVENUE).

Furthermore, we included company age as a control variable because older companies may have accumulated more slack resources, which can impact both organizational resilience and the competitive advantage. Respondents were asked to indicate the number of years their company had been in existence at the time of the survey (COMP_AGE), and we winsorized the variable at the 5th and 95th percentiles to address extreme outliers.

To account for the influence of a company’s strategic position on its competitive advantage (Porter, 1985), we included the variable STRATEGY. Respondents were asked to rate their company’s primary strategy on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Cost leadership/efficiency) to 5 (Differentiation via products/services/quality) (Becker et al., 2016; Porter, 1980).

Further, we controlled for the industry in which the companies operate (INDUSTRY) as it can have a significant impact on the competitive advantage. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected certain industries, such as tourism and events, and those with vulnerable global supply chains (Acciarini et al., 2021; Cheema‐Fox et al., 2021). Participants were asked to categorize their company into one of 13 industries, including an “other” category. We compute dummy variables for each industry and include them in our model.Footnote 5

Finally, to consider the potential influence of the respondents themselves on the assessment of organizational resilience, we included respondents’ tenure in the company (TENURE) as a control variable. This variable captures the level of experience and knowledge of the company’s processes possessed by the respondents.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Descriptive results

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 4 provide an overview of the mean values for the dependent and independent variables. The mean value for COMP_ADV_CRISIS is 3.444, which is significantly higher than the scale’s midpoint of 3 (t = 5.694, p < 0.001, one-tailed). This indicates that respondents generally perceive their companies’ situation to be better than that of their competitors during the crisis. Furthermore, concerning organizational resilience, the means for both RES_PLAN (3.888) and RES_ADAPT (4.212) are significantly above the scale’s midpoint of 3.5 (RES_PLAN: t = 4.727, p < 0.001, one-tailed; RES_ADAPT: t = 10.228, p < 0.001, one-tailed). These results suggest that the sample perceives their organizational resilience to be relatively high. Finally, regarding the determinants of organizational resilience, the mean values for RISK_MGMT and FCT_PLAN are both significantly higher than the scale’s midpoint of 3 (RISK_MGMT: mean = 3.439, t = 6.059, p < 0.001, one-tailed; FCT_PLAN: mean = 3.691, t = 12.163, p < 0.001, one-tailed). Overall, the descriptive findings indicate that the sample generally perceives their companies to have a favorable competitive position, high organizational resilience, and positive attributes related to risk management and the planning function of budgeting.

4.2 Hypothesis testing

We use covariance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze the hypothesized relationships among risk management orientation, the importance of the planning function, organizational resilience, and competitive advantage in times of crisis. Despite the inherent challenges associated with a small sample size for covariance-based SEM, the relatively low complexity of our model–characterized by constructs derived from averaged item responses supports the feasibility of our analytical approach (Hair et al., 2019).Footnote 6

To address the fact that resilience cannot be built up in the short run but is rather influenced by the company’s circumstances in normal times, we employed the surveyed items on the situation before the crisis for our independent variable FCT_PLAN. In doing so, we recognize that developing resilience requires time and is influenced by the organization’s condition before the crisis. In contrast, we anticipate that the potential performance impact of organizational resilience will become evident during a crisis. Therefore, we use responses that specifically refer to the situation during the crisis for our dependent variable COMP_ADV_CRISIS. This approach also addresses potential concerns regarding causality. By using data that refers to different points in time, we come close to establishing a causal relationship between our independent and dependent variables, but not the other way around.Footnote 7

The criteria for model fit indicate an acceptable fit of the model, with all values exceeding the common thresholds for structural equation model goodness-of-fit criteria (Hair et al., 2019). Specifically, the model’s χ2 is not significant and the χ2/df ratio is less than two, indicating an acceptable fit (Kline, 2015). Furthermore, the comparative fit index (CFI) is above the acceptable fit level of 0.90. Finally, both the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean residual (SRMR) are less than or equal to the threshold of 0.08 (χ2/df = 1.816, CFI = 0.981, RMSEA = 0.080, SRMR = 0.005). The model is presented in Table 5 and Fig. 2.

H1a and H1b postulate a positive association between risk management orientation and both factors of organizational resilience. Here, we find full support for both hypotheses because RISK_MGMT is positively and significantly associated with both RES_PLAN (β = 0.395; p = 0.001) and RES_ADAPT (β = 0.345; p < 0.001).

H2a and H2b predict that the importance of the planning function of budgeting is positively associated with both factors of organizational resilience. Again, our data support both hypotheses. We find that FCT_PLAN is positively and significantly associated with RES_PLAN (β = 0.271; p = 0.029) and RES_ADAPT (β = 0.248; p = 0.028).

Additionally, as the two factors of resilience constitute two subdimensions of the overall concept of organizational resilience, we model the covariation of the two factors and find a significant effect (β = 0.112; p = 0.011). This implies that companies should simultaneously strengthen capabilities falling under the planning and the adaptive capability factor to build resilience.

Regarding the effects of organizational resilience, H3a and H3b predict a positive association between both factors of organizational resilience and competitive advantage in times of crisis. In line with this expectation, we find that RES_ADAPT is positively and significantly associated with COMP_ADV_CRISIS (β = 0.469, p < 0.001). However, the results show no significant effect of RES_PLAN on COMP_ADV_CRISIS. Thus, we only find support for H3b, i.e., with regard to the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience. This finding can potentially be explained by the specific perspective of the planning factor of organizational resilience. The planning factor considers preparedness for crises and disruptive events that require fast responses to re-establish a working organization. This aspect of organizational resilience may have been important in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns forced companies to rearrange their working conditions. However, at the time of the survey, the pandemic had been ongoing for almost a year, and adaptive capabilities have now become more important, especially concerning the companies’ overall performance.

Furthermore, we determine the additive explanatory power of our variables of interest by calculating Cohen’s f2 effect size measure (Cohen, 1988). The results show that all significant predictor variables also have Cohen’s f2 measures greater than 0.02, indicating that the inclusion of the variables RISK_MGMT, FCT_PLAN, RES_PLAN, and RES_ADAPT increases the explanatory power of the model. Overall, the effect sizes are small, with the exception of the effect of the adaptive capability factor of resilience on competitive advantage (f2 = 0.196). Here, the effect size is considered medium.

Finally, with regard to the control variables, we find that COMP_AGE is negatively associated with competitive advantage during times of crisis (β = − 0.003, p = 0.088). Thus, older companies have a smaller competitive advantage during times of crisis. The remaining continuously scaled control variables show no significant effect on the endogenous variables in the model.Footnote 8

4.3 Additional analyses

4.3.1 Robustness checks

In the following, we conduct two types of robustness checks. First, we focus on the planning function of budgeting. Second, we consider the effect of company size.

We argue above that the importance a company places on the planning function of budgeting is likely an antecedent of different budgeting practices that should help build organizational resilience. To assess the robustness of our findings concerning the importance of the planning function, we conduct analyses in which we replace the importance of the planning function with the budgeting practices discussed earlier. Table 6 presents the results of the robustness check. We only present results for the use of advanced KPIs (KPI_ADV, dummy variable) and the binding nature of budgets concerning resources allocated (RESOURCES), as the other practices do not show significant associations with organizational resilience. Furthermore, to ensure a satisfactory model fit, we followed the approach of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and determine structural models that include only significant paths for our independent and dependent variables.

We find that KPI_ADV has a significant association with the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience but not with its planning factor. KPI_ADV captures whether companies plan more advanced KPIs such as cash flow and rentability. Cash flow planning indicates that companies are aware of their liquidity situation throughout the planned period and likely account for a sufficient financial buffer, which can be helpful in terms of adaptive capabilities.

In contrast, Model 2 shows that RESOURCES is significantly associated with RES_PLAN but not RES_ADAPT. Typically, resources are allocated based on specific action plans, which may also include preparation for unexpected events. The more binding a plan concerning the allocation of resources is, the more comprehensive the planning is likely to be. Comprehensive planning may also consider preparation for unexpected events, which likely affect the planning aspect of organizational resilience.

Taken together, the findings show that specific budgeting practices associated with the importance of the planning function indeed influence the build-up of organizational resilience. However, different practices influence different aspects of organizational resilience. In contrast, the importance of the planning function of budgeting is associated with both factors of organizational resilience. Hence, we conclude that the importance of the planning function relates to a holistic perspective that is likely helpful in the build-up of organizational resilience because it translates into different practices that address different aspects of resilience.

Our second robustness check considers the possible effect of company size. To determine the effect, we analyze two models that either exclude very large companies (revenue ≥ 1000 million euros) or very small companies (revenue < 50 million euros). Therefore, we can control for extreme outliers.Footnote 9 Table 7 reports the results of the analyses.

The results of this robustness check are essentially the same as those of our main analysis. However, the findings for the model that excludes very large companies could be considered marginally better than the findings for the model without very small companies in terms of model fit. This suggests that our model is more suited for small- and medium-sized companies.

4.3.2 Competitive advantage during business-as-usual times

In the hypothesis development for H3a and H3b, we argue that, in general, organizational resilience provides companies with a competitive advantage not only in a crisis but also in business-as-usual times. Hence, we use our questionnaire that asked for the respondents’ assessment of the companies’ comparative situation both during the crisis (i.e., starting from the first quarter of 2020) and before the crisis (i.e., until the fourth quarter of 2020). We examine the general effect of both organizational resilience factors by applying our research model but using COMP_ADV_BEFFootnote 10 instead of COMP_ADV_CRISIS as a dependent variable. Thus, we analyze the effect of organizational resilience on a company’s competitive advantage before a crisis. However, if we use the same model as in our main analysis and only replace COMP_ADV_CRISIS with COMP_ADV_BEF, the model does not show a satisfactory fit. Thus, we again follow the approach of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and take the path from RES_PLAN to COMP_ADV_BEF out of the model. The resulting model presented in Table 8 exhibits features similar to those of our main model presented in Table 5. The respective goodness-of-fit measures indicate a good model fit.

In line with the expectation that organizational resilience positively affects a competitive advantage during business-as-usual times, we find a significant and positive coefficient for RES_ADAPT and the dependent variable COMP_ADV_BEF. Furthermore, on the basis of Cohen’s f2, this effect can be considered of medium size. Thus, we conclude that organizational resilience in terms of adaptive capabilities is helpful during both business-as-usual times and times of crisis.

However, as explained above, we find no significant association between RES_PLAN and COMP_ADV_BEF. Because the planning factor of organizational resilience is primarily related to preparation for unexpected events and crises, it is not counterintuitive that this factor does not unfold its effect during business-as-usual times. Taken together, organizational resilience is an important capability both during normal times and during times of crisis. Particular attention should be paid to the adaptive capability aspect of organizational resilience if a company wants to take full advantage of the benefits of resilience.

4.3.3 Mediation analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between management control practices, organizational resilience, and competitive advantage, we conducted a mediation analysis using bootstrapping with 1,500 replications (Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008; Zhao et al., 2010). We focus on the adaptive capability factor of resilience as a possible mediator because our main analysis finds no effect of RES_PLAN on COMP_ADV_CRISIS. Moreover, we investigate competitive advantage in times of crisis (COMP_ADV_CRISIS) and during business-as-usual times (COMP_ADV_BEF). Table 9 presents the results of the mediation analysis for the dependent variables COMP_ADV_CRISIS (Panel A) and COMP_ADV_BEF (Panel B).

For competitive advantage in times of crisis, we find significant indirect effects for both a risk management orientation and the importance of the planning function, which indicates a full mediation of the independent variables on competitive advantage in times of crisis via the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience (Zhao et al., 2010). While the understanding of organizational resilience as a meta-capability that coordinates and integrates various resources and capabilities provides support for possible mediation, it is still surprising that both variables have no direct effect on a competitive advantage. However, this finding could be explained by the specific circumstances of a crisis in which organizational resilience may be of special relevance for management accounting systems to unfold their effects.

Hence, we further examine possible meditations with regard to competitive advantages before the crisis, i.e., during business-as-usual. We now find significant direct, indirect, and total effects of RISK_MGMT on COMP_ADV_BEF with the mediator RES_ADAPT. Thus, the effect of risk management orientation is only partially mediated by the adaptive-capability factor of organizational resilience. In contrast, for FCT_PLAN, we still find an indirect-only, i.e., full mediation.

These findings suggest that certain aspects of risk management directly contribute to firm performance and the development of a competitive advantage, whereas others are mediated through the adaptive capability aspect of organizational resilience. This finding aligns with prior literature, which suggests that implementing an effective risk management strategy can lead to a competitive advantage (Anton & Nucu, 2020; Blanco-Mesa et al., 2019). However, the direct effect of risk management orientation on competitive advantage only occurs in business-as-usual times. In crisis situations, risk management can only positively affect competitive advantage through the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience. This finding emphasizes the benefits of organizational resilience in crises.

Moreover, with regard to the importance of the planning function, we only find indirect effects on competitive advantage in both normal times and crises. Thus, organizational resilience in general and adaptive capability in particular are important facilitators of the planning function of budgeting concerning competitive advantages.

Taken together, our findings underline that resilience, although often not well understood and diffused in theory as well as in practice, is directly beneficial to competitive advantage and has value by bundling and steering separate capabilities and practices in the right direction.

4.3.4 Changes in corporate planning during the crisis

In our survey, we assess planning-related constructs and items at two points in time, i.e., before and during the crisis, which provides us with the opportunity to investigate changes in budgeting practices during the crisis. Table 10 presents the results of this additional analysis.

In line with the results of Becker et al. (2016), we find a significant increase in the overall importance of the planning function and in the importance of the resource allocation microfuntion during the crisis. The latter finding suggests that during crises, companies allocate scarce resources more carefully. Turning to specific budgeting practices, we find a decrease in the binding nature of plans concerning targets. This finding is reasonable because targets are much less likely to be achieved during the crisis. Hence, companies may want to reduce the pressure on their employees.

The change in budgeting practices during the crisis may also be influenced by the importance a company places on the planning function of budgeting in general (i.e. already before the crisis). Hence, we divide our sample by the median score for FCT_PLAN and analyze how the budgeting practices changed across these groups. As shown in Table 10, Panel B, we find a significant difference in the change in the number of planned KPIs and the binding nature of plans concerning resources, depending on the importance of the planning function. More precisely, our results indicate that companies that place less importance on the planning function before the crisis show a (stronger) increase in the number of planned KPIs and the binding nature of plans concerning resources.

Overall, we find that the planning function of budgeting and the resulting budgeting practices are subject to various changes during a crisis.

5 Conclusion

Against the background of the unique setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study explores the relationship between key management accounting concepts, organizational resilience, and the competitive advantage. On the basis of a survey of 127 medium- and large-sized German companies, we find that a risk management orientation is positively associated with both the planning factor and the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience. Our findings are consistent with those of Ponomarov (2012), who shows a positive association between risk management orientation and supply chain resilience. We extend these findings by investigating a more general association with organizational resilience.

In addition, we find that the importance of the planning function of budgeting is positively associated with both the adaptive capability factor and the planning factor of organizational resilience. This result agrees with the findings of a study by Baird et al. (2023), who examine the influence of the levers of control (Simons, 1995) on organizational resilience. However, we focus specifically on the orientation of a control system, namely budgeting, and, similar to Baird et al. (2023), show a positive influence of the control system on organizational resilience.

Importantly, we also find that the adaptive capability factor of organizational resilience positively affects a company’s competitive advantage both during and before a crisis. This implies that companies with higher levels of adaptive capability are more likely to outperform their competitors in times of crisis and normal business conditions. Thus, our results are consistent with those of other studies that also show a positive effect of organizational resilience on performance (He et al., 2023; Phan et al., 2024).

However, we do not find a significant association between the planning factor of organizational resilience and competitive advantage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our setting has two specific characteristics that may prevent the planning factor from being effective. First, the pandemic had been ongoing for almost a year at the time of data collection; therefore, the ability to respond immediately to a crisis was not as important as other capabilities. Second, the organizational resilience scale was developed in the context of natural disasters in New Zealand that occur regularly and for which companies can prepare relatively well. In contrast, very few companies anticipated and prepared for the unique COVID-19 pandemic scenario. Therefore, the planning factor of resilience may not capture the preparations necessary for the COVID-19 pandemic. However, given the increasing impact of the climate crisis with more frequent natural disasters, such as flooding (e.g., Dankers & Feyen, 2008), it is still essential to be prepared for emergencies and disasters. An integrated risk management approach and a focus on the planning function of budgeting can support such preparedness.

Thus, although our study focuses on the COVID-19 pandemic, our findings may also be relevant to other local and global crises. Each crisis may have unique characteristics and dynamics, but rapid decision-making, adaptive resource allocation, and innovative thinking are likely to be important for different types of crises, including natural disasters, economic downturns, and geopolitical disruptions.

Our study contributes to the emerging literature on the determinants and consequences of organizational resilience. By establishing a link between risk management, corporate planning, and organizational resilience, our study responds to calls made by Barbera et al. (2017) and Barbera et al. (2020) to examine the role of (management) accounting in strengthening organizational resilience. Moreover, by examining an indirect effect via organizational resilience, our study extends existing research on the relationship between management control systems and crises. This adds another dimension to the stream of management accounting research that investigates the effect of management control systems in crises (e.g., Becker et al., 2016; Colignon & Covaleski, 1988; Collins et al., 1997).

Although our study provides valuable insights, potential limitations arising from our research setting must be acknowledged. Our study may have been affected by self-selection bias, as companies unaffected by the COVID-19 economic crisis may not have participated in our survey, while severely affected companies may have had limited capacity to respond. In addition, our sample consisted primarily of companies with moderate crisis impact, which limits the generalizability of our findings to more severely affected organizations. Moreover, because of the nature of the pandemic crisis, data were collected at a single point in time within a relatively short time. This limitation limited our ability to examine long-term effects and changes over time. Future research could investigate the long-term effects of organizational resilience and its impact on a company’s competitive advantage. Finally, the measurement of risk management orientation in our study relied on a scale that does not explicitly capture the concept of ERM. Future research could explore various aspects of ERM more comprehensively to provide a more nuanced understanding of its relationship with resilience (Braumann, 2018).

Data availability

The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

Please note that we do not argue that the different functions contrast with each other. Instead, companies may consider all functions of budgeting relevant. However, there are trade-offs, especially between the planning function and the motivation and evaluation function. In line with these considerations, we find that, in our sample, the importance of the planning function and the motivation and evaluation function are highly and significantly correlated. However, when focusing only on the highest quartile of the planning function, both functions no longer correlate (not tabulated).

Please note that the factor of organizational resilience originally labeled “adaptive capacity” in the studies by Lee et al. (2013) and Whitman et al. (2013) was relabeled as “adaptive capability” for the sake of consistency in our paper. Furthermore, it is important to clarify that the term “adaptive capability” does not solely refer to the adaptation stage of organizational resilience. As outlined below, we argue that this aspect of organizational resilience is relevant not only to the adaptation phase but also to the coping stage. Similarly, the term “planning” does not exclusively refer to the anticipation stage, but encompasses broader aspects of planning within the context of organizational resilience.

Bergmann et al. (2020) additionally consider codification as a microfunction of planning. Because our pre-tests indicated low comprehensibility of this item, we excluded it from our survey.