Abstract

This paper studies spouses’ intrahousehold decision-making, using unique information from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions special module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources. We build an index to measure the bargaining power of the wife in household decision-making in European countries and analyze how that index correlates with household demographic characteristics. We find cross-country differences in the values of this index, although estimates show that, in general, older, relatively more educated and working spouses with higher wages, have more power in intrahousehold decision-making. Furthermore, country-level conditions correlate with spouses’ bargaining power in household decision-making. The paper provides a direct empirical exploration of intrahousehold decision-making in a cross-country setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper analyzes the factors related to spouses’ bargaining power in intrahousehold decision-making (IDM), using data from the 2010 special module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources of the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). Since the seminal work of Gary Becker on household economic behaviors (see Becker 1991), there has been a growing literature studying household and intrahousehold decisions. These studies include a range of models, theories, and empirical applications, all diverging from the classical “unitary” models that consider the household a single unit (i.e., a “black box”), and that restrict the study of intrahousehold processes. There are non-cooperative models, as in Chen and Woolley (2001), Cherchye et al. (2011), and Doepke and Tertilt (2016); cooperative models, as in Manser and Brown (1980), McElroy and Horney (1981), and Apps and Rees (2007), individual models as in Grossbard (2011), and collective models, as in Chiappori (1988, 1992).

More recently, the analysis of household economic behaviors and, in particular, intrahousehold decisions and IDM, has generated a significant literature, both theoretical and empirical.Footnote 1 There is consensus on the rejection of the classical unitary model, as some of its predictions have been repeatedly rejected (Thomas 1990; Lundberg et al. 1997; Duflo 2003), which has led to the analysis of intrahousehold decisions within a range of theoretical frameworks. For instance, in non-unitary settings, IDM has been related to spouse characteristics such as wages, earnings and income (Thomas 1990; Aronsson et al. 2001; Pollak 2005; Cherchye et al. 2015), unearned income (Blundell et al. 2007; Cherchye and Vermeulen 2008), employment (Moehling 2005), inheritance (Blau and Goodstein 2016), shocks to the economic environment (Mazzocco 2007; Chiappori et al. 2020), health and nutrition (Pitt et al. 1990), and human capital (Gitter and Barham 2008; Li et al. 2021). Other authors have studied specific decisions in the household, such as those related to household finance (Bennett 2013), commuting behaviors (Roberts and Taylor 2017; Carta and De Philippis 2018), and self-employment decisions (Campaña, Gimenez-Nadal and Molina, 2020). Some authors have found that intrahousehold decisions are correlated with inequality (Radchenko 2016). In general terms, all theoretical and empirical studies agree that favorable conditions for a given spouse, relative to the other spouse, should increase his/her bargaining power in the household, and decrease that of the partner.

Despite this growing interest in how spouses take decisions in different scenarios and from different theoretical perspectives, most of the existing analyses face a common limitation, as spouses’ bargaining power and IDM processes are, by definition, not observable (Browning et al. 2014). Thus, most of the theories and applied research rely on specific assumptions, parametric approaches, or indirect empirical analysis, and predict intrahousehold allocations, bargaining power, or IDM through observed behaviors, typically consumption or labor supply. Few authors have addressed this limitation in a household context, providing direct analyses of how spouses bargain for intrahousehold decisions and allocate household resources. To the best of our knowledge, Bargain, Lacroix and Tiberti (2018), Lise and Yamada (2019), and Velilla (2020) are among the few who have recently studied intrahousehold allocations using direct data on individual resources, with data from Bangladesh, Japan, and Spain, respectively.

Molina et al. (2023) conducted a study on intrahousehold bargaining power and resource allocation in Spain building upon the empirical analysis of Molina et al. (2023), but expanding their focus beyond a single country (Spain). The authors utilized EU-SILC data for Spain to establish an IDM index, which they assumed to represent the Pareto weight in a collective model, summarizing intrahousehold bargaining power. By employing log-linearized equations for household labor supply, as outlined by Chiappori et al. (2002), they derived a sharing rule for household income, reflecting intrahousehold bargaining power according to the collective model (Chiappori 1992; Chiappori et al. 2002). Subsequently, the authors compared the derivatives of this theoretically-derived sharing rule with the correlates of the constructed bargaining power index, positing a one-to-one relationship between bargaining power and sharing rules. The findings supported the predictions of the collective model, albeit exclusively for Spain. Thus, Molina et al. (2023) utilized EU-SILC data for Spain to estimate a collective model of household labor supply and examined its validity by comparing a theoretically-derived intrahousehold allocation rule (the sharing rule) with the IDM index.

Similar to the index of Molina et al. (2023) for intrahousehold bargaining power of women and IDM, other authors have measured women's economic empowerment in different contexts, such as health and agriculture. This includes the Demographic and Health Survey, conducted for 90 developing countries over the recent decades (despite including several changes in participating countries and modules over the survey periods), with specific questions about decision-making autonomy across multiple domains (e.g., attitude to violence, social independence, decision-making). The data from this survey is nationally representative, repeated every four to five years, and applies the same questionnaire across countries to facilitate country comparisons across time and space. Ewerling et al. (2017) use this database for African countries and construct the Survey-based Women’s Empowerment Index (SWPER). Their results show that social independence is associated with higher coverage of maternal and child interventions; while attitudes to violence and decision-making are more consistently associated with the use of modern contraception.

Another example is the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) of the International Food Policy Research Institute (Alkire et al. 2013), measuring empowerment and participation of women in the agricultural sector, first for Guatemala, Uganda, and Bangladesh in 2011, expanded in 2012 to several other developing economies. This survey-based index is an instrument aggregating five domains of decision-making (production, productive resources, income, leadership, and time use) that measure women’s empowerment (relative to men) linked to the concept of empowerment outlined in intrahousehold decision-making models. (See Lazlo et al. (2020) for a literature review of these IDM indices.) We contribute to this literature by using an alternative database, which is comparable, harmonized, and homogenized across European countries, rather than for developing economies, and focused on time use and expenditure domains in general terms, rather than on specific contexts (e.g., agriculture). We also contribute to Molina et al. (2023) by exploring a similar index, not in a single country, and not subject to a theoretical model, but providing a more general empirical exploration.

Within this framework, we use unique data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions 2010 special module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources, for eleven European countries. This survey includes several items that allow us to construct an index to measure IDM processes related to time use and expenditures. We first define an IDM index that represents the power of the wife (and therefore also characterizes that of the husband) for IDM. Next, we explore this IDM index for Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania, and Spain. To that end, we analyze how the IDM index correlates to household demographic characteristics, including husband and wife characteristics, wages, the composition of the household, and the household’s disposable income. The results show that, in general terms, higher wages, and characteristics related to better employment outcomes (e.g., older individuals, and higher formal education level) are correlated with a greater power in IDM of the partner. However, estimates also reveal country differences in these correlations. Results show country differences in IDM; Spain and Poland seem to be the countries where wives have comparatively more power, while Italy is the country in which husbands have more power in intrahousehold decisions. Finally, we study how certain country characteristics are related to the IDM index.

The contributions of the paper are twofold. First, we explore IDM using direct data on which spouse’s opinion is more important when taking certain household decisions, and then we quantify intrahousehold bargaining power in household decisions in Europe. This is a central concept in family economics, which has received attention in recent decades from a theoretical point of view. However, it is commonly unobserved and hard to measure, and has often been empirically studied indirectly, through household labor supply and consumption behaviors.Footnote 2 Second, we study how IDM relates to certain individual characteristics (i.e., we analyze microeconomic-level decision-making), including demographics, labor market outcomes, and cultural and institutional factors (i.e., the macroeconomic-level environment) that are likely to affect intrahousehold decisions, such as sex ratios, divorce rates, male and female labor force participation, and the share of women in parliaments and managerial positions. We use a cross-country setting, providing a country comparison using homogeneous data. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first empirical exploration of IDM in a cross-country setting in Europe. We thus bridge the gap in the empirical literature on intrahousehold bargaining and intrahousehold decisions, in which most existing papers have focused on specific countries.Footnote 3

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the data and variables, and Sect. 3 shows the construction of our IDM index representing the bargaining power of wives in IDM. Section 4 presents raw correlations between the IDM index and demographics, and Sect. 5 describes the econometric strategy. Section 6 describes the results, and Sect. 7 concludes.

2 Data and variables

We use data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) cross-sectional database. The EU-SILC is a comparable and multidimensional microdata conducted every year by Eurostat (since 2003), part of the European Statistical System. The EU-SILC provides data at the family and individual level for interviewed households, and includes information on income, labor characteristics, poverty, and living conditions, among other factors. We select households from the Special Module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources, for the year 2010, which is intended to provide deeper insights into the decision-making process within households, to understand the allocation of resources within the household, and to address intrahousehold inequality and standards of living (European Commission, 2010; Molina et al. 2023).

While the 2010 Special Module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources holds significant relevance, it is important to acknowledge its limitations and the concerns it raises regarding such sensitive subjects as household finances. One limitation is the presence of slightly varying wording of the Special Module items across certain countries. Missing values pose another limitation, since some survey questions were not asked in certain countries. It is worth noting that households in certain countries may provide unreliable responses, particularly concerning inquiries about household finances and the proper utilization of answer flags.Footnote 4

The sample is restricted to married and unmarried heterosexual couples, consistent with the definition of marriage in Browning et al. (2014), and Grossbard (2014). Furthermore, given that we want to understand how intrahousehold decisions are related to socio-economic attributes, such as labor supply and income, we retain spouses who report positive hours of work as part of the main analysis (Chiappori et al. 2002; Molina et al. 2023).Footnote 5 This gives us a sample of 19,439 households, each formed by a working wife and a working husband.Footnote 6 1,320 households correspond to Bulgaria, 1,681 to the Czech Republic, 1,103 to Estonia, 1,197 to France, 2,580 to Germany, 1,180 to Greece, 3,507 to Italy, 1,321 to Luxembourg, 1,638 to Poland, 1,299 to Romania, and 2,613 to Spain.Footnote 7 Other countries included in the core EU-SILC are not included in our analysis, as relevant information was not recorded for those countries.Footnote 8

We define the following variables from the EU-SILC data. The age of the spouse, defined as 2010 minus the year in which respondents were born (we define the spousal age gap as the age of the husband minus the age of the wife). We also define the maximum education level achieved, in terms of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Following Molina et al. (2023), we recode education in three categories: University education (value 1 if individuals have reached University, 0 otherwise), secondary education (value 1 if individuals have reached secondary non-compulsory education, 0 otherwise), and basic education (value 1 for those individuals who have not reached secondary non-compulsory education, 0 otherwise). From these categories, we define the spousal education gap as a variable taking value 2 (−2) if the husband (wife) has attended University and the wife (husband) has basic education only; value 0 if the husband and the wife are in the same education category, and value 1 (−1) if the husband (wife) has secondary education and the wife (husband) basic or the husband (wife) has attended University and the wife (husband) has secondary education. It is important to control for age and education. On one hand, IDM may evolve over couples’ life cycle, and the spousal age gap (e.g., relatively older husbands) may shape IDM (Theloudis et al. 2022). On the other hand, education may also relate to IDM, since relatively more educated spouses may have more bargaining power in intrahousehold decisions (Bronson 2014; Chiappori et al. 2018).

We define household composition, since being legally married or having children may have implications for intrahousehold decisions. For instance, cohabiting but unmarried partners may behave differently than married spouses as their degree of commitment may be different, whereas the presence of children has been proven to be related to household behaviors, for example through investments in human capital or transfers (Chiappori and Weiss 2007; Chiappori et al. 2017). In doing so, we define the number of kids present in the household, the number of individuals in the household, and a dummy variable that takes value 1 for couples who are legally married, and value 0 for cohabiting couples. We omit from the sample other demographics, such as race, the immigrant status, or the region of residence, as these data were not consistently reported for all countries.

The EU-SILC includes information on household and individual incomes. Since we want to know how IDM relates to employment attributes, we take data on spouses’ wage rates, self-employment status, and household disposable income.Footnote 9 Spouses’ wage rates cover the ratio of annual labor earnings over annual hours of work.Footnote 10 Spouses’ self-employment status is a dummy variable taking value 1 for self-employed workers, and value 0 for employees. Household disposable income is measured in Euros per year, and defined as the sum, for all household members, of personal income components (cash or near cash income, company car, cash benefits or losses from self-employment, pensions received from individual private plans, unemployment benefits, old-age benefits, survivor benefits, sickness benefits, disability benefits, education-related allowances, income from rental of a property or land, family/child-related allowances, social exclusion not classified elsewhere, housing allowances, inter-household cash transfers, interest, dividends, profit from capital investments in unincorporated business, and income received by individuals under age 16), net of taxes.

Summary statistics of the variables for the whole sample are shown in Table 1, including sample weights provided by the EU-SILC data to make samples representative. The average age of husbands (wives) in the sample is 44.2 (41.7) years old, and 16.7% (15.0%) have basic education only, 48.2% (48.6%) have secondary education, and 35.1% (36.3%) have gone to a University. The average husband earns €13.4 per hour, and the average wife earns €10.6 per hour, and 13.7% (8.5%) of husbands (wives) are self-employed. (Summary statistics by country are available upon request.)

3 The intrahousehold decision-making index

The 2010 Special Module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources of the EU-SILC data includes several items about who – and how – decisions are taken in the household. Following Molina et al. (2023), we construct an index aimed at measuring the bargaining power of wives in IDM, using Principal Components Analysis (PCA). We consider the responses to these items by wives in the sample, which are recoded so that value 1 always represents the wife’s opinion being more important than that of the husband, value -1 represents the husband’s opinion being more important than that of the wife, and value 0 represents both opinions being of equal importance. Thus, positive values indicate that, for a given survey item, the wife has more influence on that decision, whereas negative values indicate that the husband has more influence, and close to zero values represent joint, balanced decision-making. Survey items are shown in Table 2, and it is important to note that these items are mostly focused on expenditures and time uses, but ignore other dimensions of intrahousehold decisions (Kabeer 1999), which may represent a limitation of the analysis.

The intuition for our baseline codification is as follows. We consider that a given wife whose opinion is, in general terms, more important in household decisions has more power than a similar wife whose opinions are often not relevant and whose husband has the last word on household decisions regarding expenditures and time uses.Footnote 11 This intuition is related to collective household models (Chiappori 1988, 1992), which assume that intrahousehold bargaining power is unobserved but can be identified through observed behaviors, and our IDM index could be interpreted as a proxy for this unobserved bargaining power (which is often called “Pareto weight”). However, although IDM could help to understand bargaining power, it is not clear if it really represents it. For instance, a wife whose opinion is relevant on certain decisions (e.g., consumption of non-durables) does not necessarily have more bargaining power than a counterpart whose opinion is not relevant (the former may be in charge of everyday shopping, which may hold her back).Footnote 12 Then, our analysis represents IDM, and conclusions regarding intrahousehold bargaining power should be treated with caution in a collective setting.

Descriptive statistics of IDM items are shown in Table 8 in Appendix A. In general, wives appear to have more importance than husbands in decisions related to everyday shopping, general decisions, and decisions related to leisure. The husband seems to have more power than the wife in decisions related to the uses of money. Averages close to zero are observed for decisions related to the consumption of durables, and the use of savings, indicating that the importance of both members of the couple is equally balanced. Table 8 shows differences across countries, suggesting that different social norms, values, or culture may shape such decisions. The analysis of how social values and culture affect intrahousehold decisions is beyond the scope of this paper, and we refer to prior analyses by Duflo and Udry (2004), Sevilla-Sanz, Giménez-Nadal and Fernández (2010), Bethmann and Rudolf (2018), and Arora and Rada (2020). Table 8 indicates that, overall, husbands tend to have more power in intrahousehold decisions in Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, and Germany, whereas wives have more important roles in household decisions in Spain, Poland, Luxembourg, and the Czech Republic. Household decisions in Estonia, France, and Romania appear to be taken in a neutral balance between husbands and wives.

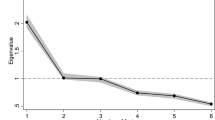

We first study whether a PCA is suitable, and we compute a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.693, beyond the threshold of 0.6 commonly proposed (Kaiser 1974; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). This points to the appropriateness of the PCA for this sample. Further, we compute Bartlett’s Sphericity test, to study whether the correlation matrix of the items is the identity matrix. We reject the null hypothesis at standard levels (p < 0.001), pointing to the existence of correlations among the items, thus suggesting that the PCA is appropriate. We then run the PCA on the whole sample and find that these six items can be merged into one factor with an eigenvalue greater than unity at standard levels.Footnote 13 We find a second factor for which the point estimate of the eigenvalue is greater than unity, but following Molina et al. (2023), we discard it, since the 95% confidence interval for the eigenvalue includes value 1 (see Fig. 2 in the Appendix).

Table 3 shows the main statistics of the PCA analysis, as well as the factor loadings used to merge the six survey items into a single IDM index. Given that every coefficient is estimated to be positive, we conclude that the interpretation of this index is equivalent to the interpretation of the single survey items; in other words, positive values represent households in which the wife has more bargaining power in intrahousehold decisions, in general terms, whereas negative values indicate that the husband has more power, and values close to zero represent households in which decisions are equally balanced between husbands and wives.

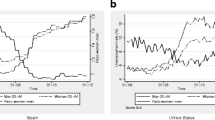

Figure 1 shows box plots of the IDM index, for each of the countries in the sample, showing the median values of the index, interquartile ranges, and whiskers (i.e., the first quartile minus 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the third quartile plus 1.5 times the interquartile range). Figure 1 then allows us to explore how the index varies within countries. We show that the index has significant variability in France and Luxembourg, suggesting that intrahousehold decisions are quite heterogeneous across households in those countries. Conversely, variability is small in the Czech Republic, Germany, Poland, and Spain, suggesting smaller heterogeneity in how the IDM index varies across households in those countries.

Distribution of IDM. Note: The sample (EUSILC 2010 intrahousehold decisions module) is restricted to households formed by (married or unmarried) working spouses. The represented variable (the IDM index) is a standardized factor; negative values represent the husband being prevalent in intrahousehold decisions; positive values represent the wife being prevalent in intrahousehold decisions; zero values represent a balance between husbands and wives in IDM

4 Descriptive evidence

We now compute Pearson pairwise correlation coefficients, and the associated statistical significance, of demographics on one hand, and the IDM index that represents the power of the wife in household decisions on the other. Results are shown in Table 4, for each of the countries in the sample, while Table 9 in the Appendix shows correlations for the full sample. Husbands’ age is positively correlated with the IDM index in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland, and Spain, while in France the correlation is negative. The age of the wife is positively correlated with the index in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Poland, and Spain. Regarding education, one generalized result is that the education of the husband is negatively correlated with the IDM index, as we estimate positive correlation coefficients between lower education levels and the index in the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain. Negative correlates are associated with University education in the same countries, and in Luxembourg. Conversely, the education level of the wife is correlated with the IDM index more heterogeneously.

For spouses’ labor attributes and wages, husbands’ self−employment status (relative to being an employee) is correlated with reduced IDM index values in the Czech Republic, France, Greece, and Poland. The self−employment status of the wife, however, seems not to be correlated with the index. Husbands’ higher wages are correlated with decreased bargaining power of wives in intrahousehold decisions in the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, and Spain. Conversely, the raw correlation between wives’ wages and the IDM index is positive and significant in France, Germany, Italy, and Luxembourg. In Poland and Spain, this correlation is negative and significant. Regarding household composition and disposable income, Table 4 shows that wives have, on average, more power in IDM in Bulgaria, but less in Germany. The number of kids is positively correlated with the index in the Czech Republic, Poland, and Spain, and the same is estimated for the number of family unit members. Household disposable income, on the other hand, is negatively correlated with the index in Estonia, Germany, Italy, and Poland.

5 Empirical strategy

Despite that the raw correlations analysis shown in Table 4 may serve as a first step in the analysis of IDM and household characteristics, in the previous analysis we do not control for other factors that may affect these relationships (Gimenez−Nadal, Molina and Velilla, 2018). To partially address this limitation, we now analyze these relationships, net of the effect of other socio−demographic characteristics. In doing so, for each household j in country c, we estimate the following equation:

where \({\mu }_{jc}\) represents the IDM in household j in country c, \({X}_{hjc}\) is a vector of socio−demographics of the husband in household j of country c (including age, education, self-employment status, and wage rate), \({X}_{wjc}\) is a vector of socio-demographics for the wife (including self-employment status, and wage rate), and \({X}_{fjc}\) is a vector of household characteristics (i.e., spouses’ age and education gap, whether the couple is married, the number of kids, the family size, and household disposable income).Footnote 14 Parameter \({\delta }_{c}\) represents country fixed effects, and \({\varepsilon }_{jc}\) is the error term. Estimates of Eq. (1) include robust standard errors clustered at the country level, and original household weights provided by the EU-SILC are used. For spouses’ education, we consider basic education as the reference category. We also include country dummies, considering Bulgaria as the reference country.

Equation (1) is estimated using OLS for the whole sample. Country fixed effects partially capture potential differences across countries, such as systematic differences in wages, education levels, or rates of self-employment, in addition to cultural and identity differences. Furthermore, coefficients associated with country dummies in these pooled estimates allow us to compare countries in terms of intrahousehold bargaining power, net of husband, wife, and household observable characteristics. Nevertheless, pooled estimates may suffer from bias arising from potential different behaviors among economies, and therefore results may not be representative for certain countries. We also estimate Eq. (1) separately for the subsamples of households residing in each of the analyzed countries. These cross-country estimates omit country fixed effects.

6 Results

6.1 Pooled results

Table 5 shows estimates of Eq. (1) for the whole sample, including the full set of regressors. It is important to note that several correlations estimated in Table 4 differ from the conditional correlations estimated in Table 5. This strongly suggests that considering the full set of male, female, and household attributes is required to capture the conditional correlation between the considered regressors and the IDM index that represents the bargaining power of wives in household decisions, net of observable characteristics.

The results show negative coefficients associated with husbands’ University education, self-employment status, and wage rate. This indicates that wives of older and highly educated husbands, of self-employed husbands, and of husbands with high wages, have relatively less power in IDM than do wives of younger, less-educated and employee husbands, who have lower wages. On the other hand, the coefficients associated with wives’ self-employment status is not statistically significant at standard levels, but wives who earn more have more power in IDM, relative to wives with lower wages. Furthermore, in couples in which the husband (wife) is comparatively older than the wife (husband), he (she) has more power in household decisions than in similar couples in which spouses’ age gap is smaller. This indicates that the oldest partner has more power in IDM processes. Similarly, the coefficient associated with spouses’ education gap is negative and highly significant. Then, the partner with the highest level of education (relative to the other partner) has more power in intrahousehold decisions. Coefficients associated with household composition seem not to be statistically significant at standard levels, and household disposable income is correlated with increased bargaining power of wives. These results are consistent with several theories of intrahousehold bargaining power, such as the collective model (Chiappori 1988, 1992), market models (Grossbard-Shechtman and Neuman 1988; Grossbard-Shechtman, 1993), and labor supply life-cycle models (Blundell et al. 2016), among others.

Coefficients associated with country dummies (i.e., country fixed effects) are shown in Table 10, indicating those countries where wives have more intrahousehold bargaining power, net of demographics of the husband, the wife, and the household. Estimates are in line with descriptive results shown in Fig. 1. Spain and Poland are countries where wives have comparatively more power in IDM processes, followed by the Czech Republic. Contrarily, Italy is the country where wives have a relatively lower power in intrahousehold decisions. Estimates for individual decision-making survey items are shown in Table 11 in the Appendix, and results are robust to the main estimates shown in Table 5.

6.2 Results by country

Table 6 presents country-specific estimates for Eq. (1). In Column (1), the estimates pertain to Bulgarian households, indicating positive conditional correlations between the IDM index and husbands' age. A negative relationship is observed between the index and the education gap among spouses, suggesting that more educated wives hold greater power in terms of IDM compared to less-educated wives. Wage rates and household composition, however, show no statistical significance at standard levels. The findings imply that, among Bulgarian couples, intrahousehold decisions are primarily influenced by education levels and age rather than wages and household composition.

Column (2) pertains to the Czech Republic. The husband's age positively correlates with the IDM index, while his self−employment status and wage rate exhibit a negative correlation. This suggests that wives of young, self-employed, and well-paid husbands possess less power in intrahousehold decisions. Labor attributes of wives show no statistical significance, but age gaps and education gaps exhibit a negative correlation with the index. This indicates that relatively older and more educated wives, compared to their husbands, have greater power in intrahousehold decisions. Other household-level attributes do not exhibit statistical significance.

Column (3) applies to Estonia, but none of the coefficients display statistical significance at standard levels. The only significant coefficient (at the 10% level) pertains to the husband's age, suggesting that older husbands have slightly less power in intrahousehold decisions compared to younger husbands. This implies that spousal age, education, employment outcomes, and household composition have limited influence on power allocation for intrahousehold decisions in this country.

The results for Romania, in Column (10), align with those of Estonia. Further research should focus on exploring other characteristics that shape intrahousehold bargaining power in decision-making within these countries, such as national and regional laws affecting divorce, parental leave, child custody, culture and identity, sex ratios, or inheritances.

Column (4) shows results for France, indicating that self-employed husbands and husbands with higher wages possess relatively more power in intrahousehold decisions compared to employee husbands and husbands with lower wages. Likewise, wives with higher wages exhibit more power in intrahousehold decisions compared to those with lower wages. These results are close to conclusions by Donni and Moreau (2007) in a collective setting. Age and education gaps display significance at the 10% level, suggesting that greater age gaps and husbands' comparatively higher education contribute to the husband's power in intrahousehold decisions. However, household composition and household disposable income do not have statistical significance at standard levels.

Column (5) presents estimates for households in Germany, which are very similar to the results for France, with the exception that husband’s self-employment status is not statistically significant in Germany. The remaining results in Germany align qualitatively with those of France.

In Greece (Column 6), when the husband has secondary education (but not a university degree), the wife holds relatively more power in intrahousehold decisions, while husband’s self-employment status and wages do not exhibit statistical significance at standard levels. The labor conditions of the wife also do not display statistical significance. However, when the wife is relatively more educated than the husband, she possesses more power in intrahousehold decisions, with a negative and significant coefficient associated with the spouses' education gap at the 10% level. Conversely, husbands possess more power in intrahousehold decisions among legally married couples compared to unmarried couples.

Column (7) presents results for Italy. Variables associated with male characteristics indicate that husbands with only secondary education possess less power in intrahousehold decisions, while wives with higher wages possess more power. The remaining coefficients do not exhibit statistical significance at standard levels, suggesting that intrahousehold decisions in Italy are not strongly influenced by individual and household characteristics. This is in contrast to Chiuri's (2000) findings, indicating that age, education, and the presence of children are significant factors in determining intrahousehold decisions.

Estimates for Luxembourg are displayed in Column (8). The IDM index is found to be negatively correlated with husbands' wage rates, while other husband characteristics do not display statistical significance at standard levels. Self-employed wives are estimated to possess less power in intrahousehold decisions compared to employee wives, although wife wages do not have statistical significance. Larger age gaps in couples are associated with a decreased role of the wife in intrahousehold decisions, but the remaining household characteristics do not have statistical significance at standard levels. Further research is needed to examine whether other attributes, such as regional differences or local laws, correlate with intrahousehold decisions in Italy and Luxembourg.

Results for Poland are shown in Column (9), indicating that the IDM index is primarily related to husband attributes rather than wife or household characteristics. The estimates suggest that more educated husbands possess more power in intrahousehold decisions compared to less educated husbands. Self-employed husbands also possess more power compared to employee husbands in intrahousehold decisions. Conversely, husband wages do not exhibit a statistically significant relationship with the IDM index.

Finally, Column (11) presents estimated coefficients for Spanish families. Husband age is positively correlated with the index, while higher-educated husbands possess more power in intrahousehold decisions than less-educated husbands. Husband self-employment status does not have statistical significance, but husband wages exhibit a negative relationship with the index, indicating that well-paid husbands in Spain possess more power in household decisions compared to poorly-paid husbands (Crespo 2009; Velilla 2020). Wife self-employment status and wage rates do not exhibit a statistically significant relationship with the index. However, the education gap suggests that higher education gaps correlate with increased values of the index (in line with Crespo 2009), while the number of children and household disposable income also exhibit a positive correlation with the index, representing the power of the wife in household decisions.

In conclusion, the estimates in Table 6 highlight the heterogeneity in the allocation of intrahousehold bargaining power for decision-making among the analyzed countries. The findings indicate that characteristics associated with improved employment outcomes for a spouse, such as older age, higher education, higher earnings, or non-labor income, tend to correlate with greater bargaining power within the household. However, it is crucial for policymakers to consider that measures aimed at reducing intrahousehold gender inequality may have varying effects in different countries. Additionally, the results emphasize the prevalent role of husbands in European households.

Future research should delve into the potential pathways and cultural elements that contribute to these associations. For example, the examination of institutional factors like public spending on families or the availability of maternity and paternity paid leave could be important in understanding intrahousehold decision-making (Campaña et al. 2023). Moreover, cross-country variations could be explained by distinct cultural and social values, as societal norms play a role in shaping perspectives on topics such as women's participation in the labor market or gender roles within households (Sevilla-Sanz 2010; Campaña et al. 2023). Additionally, religiosity may offer insights into country differences, as it influences household decision-making (Yang et al. 2019), and could potentially impact intrahousehold decision-making as well.

6.3 Bargaining power and national characteristics

Tables 5 and 6 examine the relationship between individual characteristics and the IDM index, accounting for country fixed effects. Prior theoretical studies have explored how various country characteristics influence intrahousehold decisions, by examining their impact on observed household behaviors, such as consumption, labor supply, leisure, and unpaid work. These country-level characteristics encompass factors related to distribution, laws, and other variables. For instance, several studies have linked observed household behaviors (and therefore intrahousehold decisions indirectly) to gender ratios and divorce laws. Other country characteristics that affect household decision-making include conditional cash transfer programs, parental leave policies, women's political participation, and the economic cycle.

In this study, we investigate how the IDM index correlates with a set of country characteristics. We estimate Eq. (1) while replacing country fixed effects with a vector of country characteristics. These include the gender ratio, divorce rates, male and female employment rates, the percentage of women in managerial positions, the percentage of women in parliaments, and countries' real GDP growth. The gender ratio is calculated as the number of females divided by the number of males in each country and age cohort (15–24 years, 25–39 years, 40–59 years, and 60 + years), using data from online Eurostat Tables. Divorce rates are derived from Eurostat's divorce indicators, showing the number of divorces per 100 marriages in each country. Employment rates, disaggregated by gender, are obtained from online Eurostat data and indicate the percentage of the working-age population that is employed. The share of females in managerial positions is defined based on Eurostat's Labor Force Survey Tables, while the share of women in parliament is determined using data from the European Institute for Gender Equality, representing the percentage of seats held by women in national parliaments and governments. Real GDP growth rates are sourced from Eurostat's online databases. As these characteristics vary only among countries and not within countries (due to the limited time variation in the EU-SILC sample, which is limited to the year 2010), the analysis is conducted using pooled sample estimates.

Table 7 presents estimates of the country-level coefficients, while Table 12 in the Appendix displays estimates of spouses' attributes and household demographics, which remain robust to the presence of either country fixed effects or country-level variables. All country factors are included simultaneously, although one-by-one inclusion is available upon request. The results indicate that gender ratios exhibit a positive and statistically significant correlation with the IDM index. These findings align with the conclusions drawn by Amuedo-Dorantes and Grossbard (2007) and Haddad (2015), although those studies observe the effects through household labor supply behaviors. Divorce rates demonstrate a positive association with the index, while female labor participation displays a negative correlation. These results are consistent with Voena's (2015) findings that divorce influences intrahousehold decision-making related to resource allocations, as well as Shibata et al.'s (2020) discovery that women's fear of divorce is linked to reduced power in such decision-making. Of the variables related to women's status, only the coefficient associated with the representation of women in parliaments shows statistical significance, indicating a positive correlation with the IDM index. This result aligns with several studies that have established a relationship between social norms surrounding women and their observed behaviors (e.g., Maden and Schneebaum, 2013; Lanau and Fifita 2020; Campaña et al. 2023), which may reflect intrahousehold decision-making. However, there is no correlation between GDP growth and the IDM index.

The estimates presented in Table 7 lead to several conclusions. They provide evidence of a correlation between gendere ratios and the power dynamics in intrahousehold decisions. Specifically, in country and age cohorts where females outnumber males, wives tend to possess more power in intrahousehold decisions. This finding contrasts with marriage market theories that assume lower gender ratios would increase wives' power in the household. Further research utilizing more detailed information, such as gender ratios defined by region rather than country, could shed light on this divergence. Estimates related to divorce rates suggest that societies with higher divorce rates tend to empower women more in intrahousehold decisions compared to more traditional societies with lower divorce rates. Moreover, the estimates concerning employment rates indicate that in countries with higher female employment rates, husbands generally hold more power in intrahousehold decisions, compared to countries with lower female employment rates. This counterintuitive result may be attributed to the specific survey items included in the EU-SILC survey, which only capture intrahousehold decisions pertaining to time use and expenditure. Further analyses exploring different dimensions of intrahousehold decisions can help address this point. Finally, the estimates suggest that female participation in politics, a measure of cultural and social norms (Campaña et al. 2018), is correlated with greater power for wives in intrahousehold decisions.

6.4 Robustness checks and additional results

An important note is that all the results shown previously are based on a factor derived from a series of survey items responded to by wives in interviewed households. Thus, the results may, crucially, depend on the definitions of those factors. In that context, we have run three additional analyses, which serve as robustness checks for the empirical results. Details are shown in Appendix B. First, our baseline codification of survey items assumes that wife’s solo decision-making relates to more power in intrahousehold decisions. However, it may be that joint decisions also relate to egalitarian couples and a larger role of the wife in household decisions. Then, we have re-done the empirical analysis using an alternative codification of survey items, which takes value 1 if the wife participates in the respective decision-making, or value 0 if only the husband participates in said decision-making. Second, our baseline analysis is based on wife responses to survey items, but it may be the case that wife and husband responses differ, and that discrepancies may produce different results. To tackle a potential source of bias, we re-do the analysis but using husband responses to survey items (coded as in the baseline). Third, the sample for the main analysis is restricted to households in which both spouses report positive hours of work (since one of the main demographics we include in the analysis is wage rates, which are not defined for non-working individuals). However, that sample requirement excludes an important household outcome, i.e., who gets to work. We tackle that by re-doing the analysis to include all households (and estimating a first-stage wage equation to predict wages and address missing wages for non-working individuals).Footnote 15

Table 14 shows details of the PCA analysis using the three alternative definitions for the IDM index. Column (1) focuses on the alternative recodification of dummies; Column (2) shows results for husband responses to survey items; and Column (3) shows results for the sample including non-working couples. All the factor loadings are qualitatively similar to the main results in Table 3, and KMO measures and Bartlett test p-values also remain quantitatively similar and point to the appropriateness of the PCA. Furthermore, in all three alternative approaches, we find one single factor with an eigenvalue greater than unity. Table 15 shows the correlation matrix between the baseline and all three additional approaches to the intrahousehold bargaining power index. Correlations are all positive and highly significant, indicating that the four indices are highly correlated.

Finally, Table 16 in Appendix B shows pooled estimates (with country fixed effects, and with the national indices) for the alternative approaches to the IDM index. In general terms, and despite small differences, results remain robust. The most notable differences emerge in terms of the national indices, suggesting that the way in which these variables correlate with intrahousehold decisions is more sensitive to the definition of the latter than the individual attributes. In summary, the correlations between spouses’ education, self-employment status and wages, and spouses’ age and education gaps remain qualitative and quantitatively similar. Furthermore, results for the sample including non-working spouses indicate that a working partner has relatively more power in intrahousehold decisions than a similar non-working partner. Tables 17, 18, and 19 show by-country estimates on the three alternative approaches, respectively, and the results remain qualitatively similar to the baseline case.Footnote 16

7 Conclusions

This paper explores the shifters and underlying forces in intrahousehold decision-making, using data from the 2010 special module on Intrahousehold Sharing of Resources of the EU-SILC database, for Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania, and Spain. Using information reported by households on how intrahousehold decisions are taken, and who has the most power in such decisions, we first construct an overall IDM index that represents wives’ power in household decisions, relative to the power of husbands. This is the first direct empirical analysis of IDM in a cross-country setting, complementing prior research that has focused on single countries. The paper also studies the determinants of IDM, finding that the wife’s favorable conditions, such as higher education, and higher wages, relative to the husband’s, are correlated with increases in her power in household decisions. We also find country differences in how wife, husband, and household characteristics relate to IDM. Our results suggest that the IDM is correlated with certain country characteristics, such as gender ratios, divorce rates, employment levels, and the participation of women in Politics.

The analysis has certain limitations. First, the data is cross-sectional, and therefore the analysis is limited to the estimation of conditional correlations, as it is subject to potential endogeneity, reverse causality, and unobserved heterogeneity. Thus, the results should not be interpreted as causal links. Furthermore, intrahousehold bargaining power and IDM processes are, by definition, unobservable, and when we define an index for IDM from specific survey items, we cannot determine the accuracy of the index. For instance, the survey items focus on decisions related to expenditures and time use, but ignore other dimensions of household decisions, such as allocation of resources. Relatedly, the index is defined from a PCA, and is a standardized measure. As a consequence, the interpretation of the empirical results is unclear from a quantitative perspective. In other words, although the analysis allows us to identify which characteristics relate to increased or decreased roles of partners in intrahousehold decisions, we cannot draw conclusions in terms of how a certain increase in a given characteristic translates into a specific number of wives achieving equal power in household decisions. In addition, the availability of information for the bargaining power index is limited to the 2010 wave of the data, and so we cannot provide an analysis of trends in intrahousehold bargaining power. Finally, the European Commission's report (2010) highlights that Eurostat's implementation of the special module is subject to variations in question wording, missing values, and the reliability of answers across different countries. Consequently, it is important to acknowledge that any cross-country differences and results derived from the data may be influenced by biases arising from these limitations.

Despite these limitations, certain conclusions can be drawn. First, to the best of our knowledge, we provide the first direct analysis of IDM in a group of European countries, rather than focusing on a single-country analysis. Results complement certain theories of intrahousehold decisions from a range of perspectives through household-observed behaviors (e.g., consumption or labor supply), and our estimates are in line with the predictions of these theories. Second, the results indicate that in some countries a potential source of inequality may arise from intrahousehold issues (Chiappori and Meghir 2015), but that inequality differs across economies. For instance, Greece and Italy appear to be the countries in which wives have comparatively less power in household decisions, and thus intrahousehold inequality could be especially important in those countries, compared to other countries, like Spain and Poland, where wives have comparatively more power in household decisions. Planners should consider the results of this paper, since they could help in addressing specific policies, such as cash transfers, education, and self-employment promotion policies, or schemes aimed at addressing poverty.

Notes

The paper also relates to Lechene, Pendakur and Wolf (2022), who provide an indirect study of cross-country bargaining power using data on expenditures.

For a more comprehensive understanding of these limitations and concerns, we recommend referring to the detailed discussion provided in the European Commission's report (2010).

We also analyze the full sample of working and non-working spouses as an additional result, which allows us to explore how who gets to work relates to IDM.

Given that the Special Module is only filled-in by the core EU-SILC respondents who are between 22 and 65 years old (inclusive), we do not apply any age restriction that minimizes the role of time-allocation decisions over the life cycle (Aguiar and Hurst 2007; Gimenez-Nadal and Sevilla 2012). We drop from the sample outlier observations in terms of relevant variables, using the Billor, Hadi and Velleman (2000) blocked adaptive computationally efficient outlier nominators’ algorithm for multivariate data.

To ensure the appropriateness of our sample, we applied specific criteria. Firstly, we excluded countries that lacked information on the special module. Secondly, we excluded countries that did not provide data on the variables utilized throughout our analysis. Lastly, we omitted countries with small sample sizes, typically defined as having less than 1,000 observations.

We focus on wages, rather than on individual incomes, as existing research has documented that it is wages and not income that shapes intrahousehold bargaining power (Pollak 2005).

Labor incomes are defined as the sum of individual sources of labor income (net cash plus non-cash individual income from labor, plus net self-employment benefits in the case of self-employed workers), in Euros per year. Hours of work are excluded from the analysis, as labor supply is determined by spouses’ bargaining power in intrahousehold decisions, and studying labor supply as a determinant of intrahousehold decisions would not be in line with existing theoretical and empirical research (Chiappori 1988, 1992, 2020).

Although this is our baseline codification inspired by Molina et al. (2023), as additional results, we focus on two alternative approaches. First, we focus on responses to survey items given by husbands, and not by wives, as responses of wives and husbands may show discrepancies. Secondly, we recode items so that value 1 represents the wife taking part in those decisions (either being more important or balanced with the husband), 0 if the husband’s opinion is the most important. Results are similar.

Relatedly, Safilios-Rothschild (1976) differentiates between spouses who have the “orchestration power” in the household (i.e., spouses who make the important but infrequent decisions that determine life styles and major characteristics of families), and spouses who have “implementation power” (i.e., those who make everyday but unimportant decisions). See Box 1 in Ponthieux (2013) for a summary of the related literature in Sociology.

Given that we want an index that represents the bargaining power of wives in IDM, it is important to note that running a PCA for every individual country would prevent us from studying country differences, as all computed factors would have zero mean. Since studying country differences is among our main objectives, we therefore compute the PCA for the whole sample, though we checked that analysis at the country level provided similar results (i.e., a similar derived factor).

We control for spouses’ age and education gap, instead of including wives’ age and education, as gaps may be more informative. We also estimate equations including non-linear (quadratic) terms of ages and wage rates. However, these quadratic terms are not statistically significant. As a consequence, we retain only the linear components for simplicity.

Summary statistics of all couples, including non-working individuals, are shown in Table 13 in Appendix B; the wage equation predicts wage rates in terms of a second-order polynomial on age, education, self-employment status, marital status, household size, number of children, country, and year non-linear effects, and interactions between country dummies and the remaining variables.

We have conducted two additional robustness checks to assess the sensitivity of our results to the reliability of answers on intrahousehold decision survey questions and the presence of missing answers. First, we examine the similarity of answers between husbands and wives, finding that responses are similar in approximately 80% of households across all analyzed countries, except France (although similar conclusions are obtained when studying husbands' responses). Secondly, we analyzed the percentage of missing answers on decision-making items. Notably, only France and Poland surpassed Eurostat's cutoff of 7% for missing answers (see Table 20 in the Appendix). Excluding France, as well as France and Poland, from the main analyses yielded robust conclusions.

References

European Commission (2010) 2010 EU-SILC module on intra-household sharing of resources: assessment of the implementation. European Commission, Directorate F: Social and information society statistics, Unit F-4: Quality of life

Aguiar M, Hurst E (2007) Measuring trends in leisure: the allocation of time over five decades. Quart J Econ 122(3):969–1006

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Quart J Econ 115(3):715–753

Alderman H, Chiappori PA, Haddad L, Hoddinott J, Kanbur R (1995) Unitary versus collective models of the household: is it time to shift the burden of proof? World Bank Res Obs 10(1):1–19

Alkire S, Meinzen-Dick R, Peterman A, Quisumbing A, Seymour G, Vaz A (2013) The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Dev 52:71–91

Almas I, Armand A, Attanasio O, Carneiro P (2018) Measuring and changing control: women’s empowerment and targeted transfers. Econ J 128(612):F609–F639

Altindag DT, Nunley J, Seals A (2017) Child-custody reform and the division of labor in the household. Rev Econ Household 15(3):833–856

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Grossbard S (2007) Cohort-level sex ratio effects on women’s labor force participation. Rev Econ Household 5(3):249–278

Apps P, Rees R (2007) Cooperative household models. IZA Discussion Paper 3127

Armand A, Attanasio O, Carneiro P, Lechene V (2020) The effect of gender-targeted conditional cash transfers on household expenditures: evidence from a randomized experiment. Econ J 130(631):1875–1897

Aronsson T, Daunfeldt SO, Wikström M (2001) Estimating intrahousehold allocation in a collective model with household production. J Popul Econ 14(4):569–584

Arora D, Rada C (2020) Gender norms and intrahousehold allocation of labor in Mozambique: a CGE application to household and agricultural economics. Agric Econ 51(2):259–272

Attanasio OP, Lechene V (2014) Efficient responses to targeted cash transfers. J Polit Econ 122(1):178–222

Bargain O, González L, Keane C, Özcan B (2012) Female labor supply and divorce: new evidence from Ireland. Eur Econ Rev 56(8):1675–1691

Bargain O, Boutin D, Champeaux H (2019) Women’s political participation and intrahousehold empowerment: evidence from the Egyptian Arab Spring. J Dev Econ 141:102379

Bargain O, Lacroix G, Tiberti L (2018) Validating the collective model of household consumption using direct evidence on sharing. Partnership for Economic Policy Working Paper 2018–06

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family: enlarged edition. Harvard university press

Bennett F (2013) Researching within-household distribution: overview, developments, debates, and methodological challenges. J Marriage Fam 75(3):582–597

Bernal R, Fruttero A (2008) Parental leave policies, intra-household time allocations and children’s human capital. J Popul Econ 21(4):779–825

Bethmann D, Rudolf R (2018) Happily ever after? Intrahousehold bargaining and the distribution of utility within marriage. Rev Econ Household 16(2):347–376

Billor N, Hadi AS, Velleman PF (2000) BACON: blocked adaptive computationally efficient outlier nominators. Comput Stat Data Anal 34(3):279–298

Blau DM, Goodstein RM (2016) Commitment in the household: evidence from the effect of inheritances on the labor supply of older married couples. Labour Econ 42:123–137

Blundell R, Chiappori PA, Meghir C (2005) Collective labor supply with children. J Polit Econ 113(6):1277–1306

Blundell R, Chiappori PA, Magnac T, Meghir C (2007) Collective labour supply: heterogeneity and non-participation. Rev Econ Stud 74(2):417–445

Blundell R, Pistaferri L, Saporta-Eksten I (2016) Consumption inequality and family labor supply. Am Econ Rev 106(2):387–435

Bourguignon F, Browning M, Chiappori P-A (2009) Efficient intra-household allocations and distribution factors: Implications and identification. Rev Econ Stud 76(2):503–528

Bronson MA (2014) Degrees are forever: marriage, educational investment, and lifecycle labor decisions of men and women. Mimeo

Browning M (2000) The saving behaviour of a two-person household. Scand J Econ 102(2):235–251

Browning M, Chiappori PA, Weiss Y (2014) Economics of the Family. Cambridge University Press

Campaña JC, Giménez-Nadal JI, Molina JA (2018) Gender norms and the gendered distribution of total work in Latin American households. Fem Econ 24(1):35–62

Campaña JC, Giménez-Nadal JI, Molina JA (2020) Self-employed and employed mothers in Latin American families: are there differences in paid work, unpaid work, and child care? J Fam Econ Issues 41(1):52–69

Campaña JC, Gimenez-Nadal JI, Velilla J (2023) Measuring gender gaps in time allocation in europe. Soc Indic Res 165(2):519–553

Carta F, De Philippis M (2018) You’ve come a long way, baby. Husbands’ commuting time and family labour supply. Reg Sci Urban Econ 69:25–37

Chen Z, Woolley F (2001) A Cournot-Nash model of family decision making. Econ J 111(474):722–748

Cherchye L, Vermeulen F (2008) Nonparametric analysis of household labor supply: goodness of fit and power of the unitary and the collective model. Rev Econ Stat 90(2):267–274

Cherchye L, De Rock B, Vermeulen F (2007) The collective model of household consumption: a nonparametric characterization. Econometrica 75(2):553–574

Cherchye L, Demuynck T, De Rock B (2011) Revealed preference analysis of non-cooperative household consumption. Econ J 121(555):1073–1096

Cherchye L, De Rock B, Vermeulen F (2012) Married with children: a collective labor supply model with detailed time use and intrahousehold expenditure information. Am Econ Rev 102(7):3377–3405

Cherchye L, De Rock B, Lewbel A, Vermeulen F (2015) Sharing rule identification for general collective consumption models. Econometrica 83(5):2001–2041

Chiappori PA (1988) Rational household labor supply. Econometrica 56(1):63–90

Chiappori PA (1992) Collective labor supply and welfare. J Polit Econ 100(3):437–467

Chiappori PA (2020) The theory and empirics of the marriage market. Annu Rev Econ 12:547–578

Chiappori PA, Mazzocco M (2017) Static and intertemporal household decisions. J Econ Lit 55(3):985–1045

Chiappori PA, Weiss Y (2007) Divorce, remarriage, and child support. J Law Econ 25(1):37–74

Chiappori PA, Fortin B, Lacroix G (2002) Marriage market, divorce legislation, and household labor supply. J Polit Econ 110(1):37–72

Chiappori PA, Salanié B, Weiss Y (2017) Partner choice, investment in children, and the marital college premium. Am Econ Rev 107(8):2109–2167

Chiappori PA, Dias MC, Meghir C (2018) The marriage market, labor supply, and education choice. J Polit Econ 126(S1):S26–S72

Chiappori PA, Giménez-Nadal JI, Molina JA, Velilla J (2022) Household labor supply: Collective evidence in developed dountries. In: Zimmermann KF (ed) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Springer, Cham

Chiappori PA, Meghir C (2015) Intrahousehold inequality. In: Handbook of income distribution (Vol 2, pp 1369-1418). Elsevier

Chiappori PA, Giménez JI, Molina JA, Theloudis A, Velilla J (2020) Intrahousehold commitment and intertemporal labor supply. IZA Discussion Paper 13545

Chiuri M (2000) Quality and demand of child care and female labour supply in Italy. Labour 14(1):97–118

Crespo L (2009) Estimation and testing of household labour suply models: evidence from Spain. Investig Econ 33(2):303–335

Del Boca D, Flinn C (2012) Endogenous household interaction. J Econ 166(1):49–65

Del Boca D, Flinn CJ (2014) Household behavior and the marriage market. J Econ Theory 150:515–550

Doepke M, Tertilt M (2016) Families in macroeconomics. In: Handbook of Macroeconomics (Vol 2, pp 1789–1891). Elsevier

Donni O (2008) Household behavior and family economics. Encycl Life Support Syst Contrib 6(9):40

Donni O, Moreau N (2007) Collective labor supply: a single-equation model and some evidence from French data. J Human Resour 42(1):214–246

Duflo E (2003) Grandmothers and granddaughters: old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Econ Rev 17(1):1–25

Duflo E, Udry CR (2004) Intrahousehold resource allocation in Cote d'Ivoire: social norms, separate accounts and consumption choices. NBER Working Paper 10498

Dunbar GR, Lewbel A, Pendakur K (2013) Children’s resources in collective households: identification, estimation, and an application to child poverty in Malawi. Am Econ Rev 103(1):438–471

Ewerling F, Lynch JW, Victora CG, van Eerdewijk A, Tyszler M, Barros AJ (2017) The SWPER index for women’s empowerment in Africa: development and validation of an index based on survey data. Lancet Glob Health 5(9):e916–e923

Gersbach H, Haller H (2001) Collective decisions and competitive markets. Rev Econ Stud 68(2):347–368

Giménez-Nadal JI, Molina JA, Velilla J (2018) Spatial distribution of US employment in an urban efficiency wage setting. J Reg Sci 58(1):141–158

Giménez-Nadal JI, Campaña JC, Molina JA (2021) Sex-ratios and work in Latin American households: evidence from Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile. Latin Am Econ Rev 30:1–25

Gimenez-Nadal JI, Molina JA (2014) Regional unemployment, gender, and time allocation of the unemployed. Rev Econ Household 12(1):105–127

Gimenez-Nadal JI, Sevilla A (2012) Trends in time allocation: a cross-country analysis. Eur Econ Rev 56(6):1338–1359

Ginja R, Jans J, Karimi A (2020) Parental leave benefits, household labor supply, and children’s long-run outcomes. J Law Econ 38(1):261–320

Gitter SR, Barham BL (2008) Women’s power, conditional cash transfers, and schooling in Nicaragua. World Bank Econ Rev 22(2):271–290

Gray JS (1998) Divorce-law changes, household bargaining, and married women’s labor supply. Am Econ Rev 88(3):628–642

Grossbard S (2011) Independent individual decision-makers in household models and the new home economics. In: Molina JA (ed) Household economic behaviors. Springer, New York, NY, pp 41–56

Grossbard S (2015) Sex ratios, polygyny, and the value of women in marriage: a Beckerian approach. J Demograph Econ 81(1):13–25

Grossbard S (2014) The marriage motive: a price theory of marriage. How marriage markets affect employment, consumption, and savings. Springer New York

Grossbard-Schectman S (2019) On the economics of marriage: a theory of marriage, labor, and divorce. Routledge

Grossbard-Shechtman A (1984) A theory of allocation of time in markets for labour and marriage. Econ J 94(376):863–882

Grossbard-Shechtman S (2001) The new home economics at Colombia and Chicago. Fem Econ 7(3):103–130

Grossbard-Shechtman SA, Neuman S (1988) Womens labor supply and marital choice. J Polit Econ 96(6):1294–1302

Grossbard-Shechtman S, Neideffer M (1997) Women’s hours of work and marriage market imbalances. In: Economics of the Family and Family Policies (pp 90–104). Routledge

Haddad GK (2015) Gender ratio, divorce rate, and intra-household collective decision process: evidence from Iranian urban households labor supply with non-participation. Empir Econ 48(4):1365–1394

Hoehn-Velasco L, Penglase J (2021) Does unilateral divorce impact women’s labor supply? Evidence from Mexico. J Econ Behav Organ 187:315–347

Kabeer N (1999) Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Chang 30(3):435–464

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39(1):31–36

Lanau A, Fifita V (2020) Do households prioritise children? Intra-household deprivation a case study of the South Pacific. Child Indic Res 13(6):1953–1973

Laszlo S, Grantham K, Oskay E, Zhang T (2020) Grappling with the challenges of measuring women’s economic empowerment in intrahousehold settings. World Dev 132:104959

Lechene V, Preston I (2011) Noncooperative household demand. J Econ Theory 146(2):504–527

Lechene V, Pendakur K, Wolf A (2022) Ordinary least squares estimation of the intrahousehold distribution of expenditure. J Polit Econ 130(3):681–731

Leung MC, Zhang J (2008) Gender preference, biased sex ratio, and parental investments in single-child households. Rev Econ Household 6(2):91–110

Li L, Wu X, Zhou Y (2021) Intra-household bargaining power, surname inheritance, and human capital accumulation. J Popul Econ 34(1):35–61

Lise J, Yamada K (2019) Household sharing and commitment: evidence from panel data on individual expenditures and time use. Rev Econ Stud 86(5):2184–2219

Lundberg SJ, Pollak RA, Wales TJ (1997) Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom child benefit. J Human Resour 32(3):463–480

Mader K, Schneebaum A (2013) The gendered nature of intra-household decision making in and across Europe. Vienna University of Economics and Business Working Paper 157

Manser M, Brown M (1980) Marriage and household decision-making: a bargaining analysis. Int Econ Rev 21(1):31–44

Mazzocco M (2007) Household intertemporal behaviour: a collective characterization and a test of commitment. Rev Econ Stud 74(3):857–895

McElroy MB, Horney MJ (1981) Nash-bargained household decisions: toward a generalization of the theory of demand. Int Econ Rev 22(2):333–349

Moehling CM (2005) She has suddenly become powerful: Youth employment and household decision making in the early twentieth century. J Econ History 65(2):414–438

Molina JA, Velilla J, Ibarra H (2023) Intrahousehold bargaining power in Spain: an empirical test of the collective model. J Fam Econ Issues 44:84–97

Pitt MM, Rosenzweig MR, Hassan MN (1990) Productivity, health, and inequality in the intrahousehold distribution of food in low-income countries. Am Econ Rev 80(5):1139–1156

Pollak RA (2005) Bargaining power in marriage: earnings, wage rates and household production. NBER Working Paper 11239

Ponthieux S (2013) Income pooling and equal sharing within the household-What can we learn from the 2010 EU-SILC module. Eurostat Population and Social Conditions: Methodologies and Working Papers

Radchenko N (2016) Welfare sharing within households: Identification from subjective well-being data and the collective model of labor supply. J Fam Econ Issues 37(2):254–271

Rangel MA (2006) Alimony rights and intrahousehold allocation of resources: evidence from Brazil. Econ J 116(513):627–658

Rapoport B, Sofer C, Solaz A (2011) Household production in a collective model: some new results. J Popul Econ 24(1):23–45

Roberts J, Taylor K (2017) Intra-household commuting choices and local labour markets. Oxf Econ Pap 69(3):734–757

Safilios-Rothschild C (1976) A macro-and micro-examination of family power and love: an exchange model. J Marriage Fam 38(2):355–362

Sevilla-Sanz A (2010) Household division of labor and cross-country differences in household formation rates. J Popul Econ 23:225–249

Sevilla-Sanz A, Gimenez-Nadal JI, Fernández C (2010) Gender roles and the division of unpaid work in Spanish households. Fem Econ 16(4):137–184

Shibata R, Cardey S, Dorward P (2020) Gendered intra-household decision-making dynamics in agricultural innovation processes: assets, norms and bargaining power. J Int Dev 32(7):1101–1125

Shore SH (2010) For better, for worse: Intrahousehold risk-sharing over the business cycle. Rev Econ Stat 92(3):536–548

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB (2007) Using multivariate statistics (Vol 5, pp 481–498). Boston, MA: Pearson

Theloudis A, Velilla J, Chiappori PA, Gimenez-Nadal JI, Molina JA (2022) Commitment and the dynamics of household labor supply. IZA Discussion Paper 15737

Thomas D (1990) Intra-household resource allocation: an inferential approach. J Human Resour 25(4):635–664

Velilla J (2020) Testing the sharing rule in a collective model of discrete labor supply with Spanish data. Appl Econ Lett 27(10):848–853

Vermeulen F (2002) Collective household models: principles and main results. J Econ Surv 16(4):533–564

Vermeulen F, Bargain O, Beblo M, Beninger D, Blundell R, Carrasco R, Chiuri MC, Laisney F, Lechene V, Moreau N, Myck M, Ruiz-Castillo J (2006) Collective models of labor supply with nonconvex budget sets and nonparticipation: a calibration approach. Rev Econ Household 4(2):113–127

Voena A (2015) Yours, mine, and ours: do divorce laws affect the intertemporal behavior of married couples? Am Econ Rev 105(8):2295–2332

Yang Y, Zhang C, Yan Y (2019) Does religious faith affect household financial market participation? Evidence from China. Econ Model 83:42–50

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This paper has benefitted from funding from the Government of Aragón (Project S32_20R, funded by Program FSE Aragón 2014–2020), and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Project PID2019-108348RA-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033). J.C. Campaña acknowledges funding from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Project PID2019-111765 GB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033), and the Regional Government of Madrid (OPINBI Project H2019/HUM-5793, B.O.C.M. Num. 302). J. Velilla acknowledges funding from the Cátedra Emprender (Project C006/2021_2). We also acknowledge useful comments from the Editor, and two anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: additional results

See Fig. 2 and Tables 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12.

Scree plot of eigenvalues after PCA. Note: The sample (EUSILC 2010 intrahousehold decisions module) is restricted to households formed by (married or unmarried) working spouses

Appendix B: additional PCA results

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Campaña, J.C., Giménez-Nadal, J.I., Molina, J.A. et al. The shifters of intrahousehold decision-making in European countries. Empir Econ 66, 1055–1101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02494-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02494-8